Sexual harassment

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Layout (July 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Sex and the law |

|---|

|

Social issues |

|

Specific offences (Varies by jurisdiction) |

|

Sex offender registration |

|

Portals |

|

Sexual harassment is bullying or coercion of a sexual nature and the unwelcome or inappropriate promise of rewards in exchange for sexual favors.[1] Sexual harassment includes a range of actions from mild transgressions to sexual abuse or assault.[2] A harasser may be the victim's supervisor, a supervisor in another area, a co-worker, or a client or customer. Harassers or victims may be of any gender.[3]

In most modern legal contexts, sexual harassment is illegal. Laws surrounding sexual harassment generally do not prohibit simple teasing, offhand comments, or minor isolated incidents—that is due to the fact that they do not impose a "general civility code".[4] In the workplace, harassment may be considered illegal when it is frequent or severe thereby creating a hostile or offensive work environment or when it results in an adverse employment decision (such as the victim's demotion, firing or quitting). The legal and social understanding of sexual harassment, however, varies by culture.

Sexual harassment by an employer is a form of illegal employment discrimination. For many businesses or organizations, preventing sexual harassment and defending employees from sexual harassment charges have become key goals of legal decision-making.

Contents

1 Etymology and history

1.1 The term "sexual harassment"

1.2 Key sexual harassment cases

2 Situations

3 In the workplace

4 In the military

5 Varied behaviors

6 Prevention

7 Impact

7.1 Coping

7.2 Common effects on the victims

7.3 Post-complaint retaliation and backlash

7.4 Backlash stress

8 Organizational policies and procedures

9 Evolution of law in different jurisdictions

9.1 Varied legal guidelines and definitions

9.2 Africa

9.2.1 Morocco

9.3 Australia

9.4 Europe

9.4.1 Denmark

9.4.2 France

9.4.3 Germany

9.4.4 Greece

9.4.5 Russia

9.4.6 Switzerland

9.4.7 United Kingdom

9.5 Asia

9.5.1 India

9.5.2 Israel

9.5.3 Japan

9.5.4 Pakistan

9.5.5 Philippines

9.6 United States

9.6.1 Evolution of sexual harassment law

9.6.1.1 Workplace

9.6.1.2 Education

9.6.2 Additionally

9.6.3 EEOC Definition

9.6.3.1 Quid pro quo sexual harassment

9.6.3.2 Hostile environment sexual harassment

9.6.3.3 Sexual orientation discrimination

9.6.3.4 Retaliation

10 Historical antecedents

10.1 Ancient Rome

11 Criticism

12 In media and literature

13 See also

14 Notes

15 References

16 Further reading

17 External links

Etymology and history

The modern legal understanding of sexual harassment was first developed in the 1970s, although related concepts have existed in many cultures.

The term "sexual harassment"

Although legal activist Catharine MacKinnon is sometimes credited with creating the laws surrounding sexual harassment in the United States with her 1979 book entitled Sexual Harassment of Working Women,[5] the first known use of the term sexual harassment was in a 1973 report about discrimination called "Saturn's Rings" by Mary Rowe, Ph.D.[6] though Rowe has stated that sexual harassment was being discussed in women's groups in Massachusetts in the early 1970s, and wasn't likely the first person to use the term. At the time, Rowe was the Chancellor for Women and Work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).[7] Due to her efforts at MIT, the university was one of the first large organizations in the U.S. to develop specific policies and procedures aimed at stopping sexual harassment.

In the book In Our Time: Memoir of a Revolution (1999), journalist Susan Brownmiller quotes Cornell University activists who believed they had coined the term 'sexual harassment' in 1975 after being asked for help by Carmita Dickerson Wood, a 44-year-old single mother who was being harassed by a faculty member at Cornell's Department of Nuclear Physics.[8][9][10]

These activists, Lin Farley, Susan Meyer, and Karen Sauvigne went on to form the Working Women's Institute which, along with the Alliance Against Sexual Coercion (founded in 1976 by Freada Klein, Lynn Wehrli, and Elizabeth Cohn-Stuntz), were among the pioneer organizations to bring sexual harassment to public attention in the late 1970s. One of the first legal formulations of the concept of sexual harassment as consistent with sex discrimination and therefore prohibited behavior under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 appeared in the 1979 seminal book by Catharine MacKinnon[5] entitled "Sexual Harassment of Working Women".[11]

Key sexual harassment cases

Sexual harassment first became codified in U.S. law as the result of a series of sexual harassment cases in the 1970s and 1980s. The majority of women pursuing these cases were African American, and many of the women were former civil rights activists who applied principles of civil rights to sex discrimination.[12]

Williams v. Saxbe (1976) and Paulette L. Barnes, Appellant, v. Douglas M. Costle, Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (1977) determined it was sex discrimination to fire someone for refusing a supervisor's advances.[13][14] Around the same time, Bundy v. Jackson was the first federal appeals court case to hold that workplace sexual harassment was employment discrimination.[15] Five years later the Supreme Court agreed with this holding in Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson.

The term was largely unknown (outside academic and legal circles) until the early 1990s when Anita Hill witnessed and testified against Supreme Court of the United States nominee Clarence Thomas.[16] Since Hill testified in 1991, the number of sexual harassment cases reported in the US and Canada increased 58 percent and have climbed steadily.[16]

Situations

Dramatization of an incident done as part of a university photo project

At the Tavern, by Johann Michael Neder, 1833, Germanisches Nationalmuseum

Sexual harassment may occur in a variety of circumstances—in workplaces as varied as factories, school, college, acting, and the music business.[17][18][19][20][21][22][23] Often, the perpetrator is in a position of power or authority over the victim (due to differences in age, or social, political, educational or employment relationships). They can also be expecting to receive such power or authority in form of promotion. Forms of harassment relationships include:

- The perpetrator can be anyone, such as a client, a co-worker, a parent or legal guardian, relative, a teacher or professor, a student, a friend, or a stranger.

- The place of harassment occurrence may vary from different schools[24] workplace and other.

- There may or may not be other witnesses or attendances.

- The perpetrator may be completely unaware that his or her behavior is offensive or constitutes sexual harassment. The perpetrator may be completely unaware that his or her actions could be unlawful.[3]

- The incident can take place in situations in which the harassed person may not be aware of or understand what is happening.

- The incident may be a one time occurrence but more often the incident repeats.

- Adverse effects on the target are common in the form of stress, social withdrawal, sleep, eating difficulties, and overall health impairment.

- The victim and perpetrator can be any gender.

- The perpetrator does not have to be of the opposite sex.

- The incident can result from a situation in which the perpetrator thinks they are making themselves clear, but is not understood the way they intended. The misunderstanding can either be reasonable or unreasonable. An example of unreasonable is when a woman holds a certain stereotypical view of a man such that she did not understand the man’s explicit message to stop.[25]

With the advent of the internet, social interactions, including sexual harassment, increasingly occur online, for example in video games or in chat rooms.

According to the 2014 PEW research statistics on online harassment, 25% of women and 13% of men between the ages of 18 and 24 have experienced sexual harassment while online.[26]

In the workplace

This section is in a list format that may be better presented using prose. (March 2018) |

The United States' Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) defines workplace sexual harassment as "unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitute sexual harassment when this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual's employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual's work performance, or creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment” (EEOC).[27]

- 79% of victims are women, 21% are men

- 51% are harassed by a supervisor

- Business, trade, banking, and finance are the biggest industries where sexual harassment occurs

- 12% received threats of termination if they did not comply with their requests

- 26,000 people in the armed forces were assaulted in 2012[28]

- 302 of the 2,558 cases pursued by victims were prosecuted

- 38% of the cases were committed by someone of a higher rank

- Sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination that violates the Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

- The Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is a federal law that prohibits employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of sex, race, color, national origin, and religion. It generally applies to employers with fifteen or more employees, including federal, state, and local governments. Title VII also applies to private and public colleges and universities, employment agencies, and labor organizations.[29]

- “It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an employer … to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

- The Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is a federal law that prohibits employers from discriminating against employees on the basis of sex, race, color, national origin, and religion. It generally applies to employers with fifteen or more employees, including federal, state, and local governments. Title VII also applies to private and public colleges and universities, employment agencies, and labor organizations.[29]

In the military

Studies of sexual harassment have found that it is markedly more common in the military than in civilian settings.[30][31] A Canadian study found that key risk factors associated with military settings are the typically young age of personnel, the 'isolated and integrated' nature of accommodation, the minority status of women, and the disproportionate number of men in senior positions.[32] The traditionally masculine values and behaviours that are rewarded and reinforced in military settings, as well as their emphasis on conformity and obedience, are also thought to play a role.[33][34][35][36][37] Canadian research has also found that the risk increases during deployment on military operations.[38]

While some male military personnel are sexually harassed, women are substantially more likely to be affected.[38][30][39][40] Women who are younger and joined the military at a younger age face a greater risk, according to American, British and French research.[41][42][43]

Child recruits (under the age of 18) and children in cadet forces also face an elevated risk. In the UK, for example, hundreds of complaints of the sexual abuse of cadets have been recorded since 2012.[44][45][46] In Canada, one in ten complaints of sexual assault in military settings are from child cadets or their parents.[44][45][46][47][48]

Individuals detained by the military are also vulnerable to sexual harassment. During the Iraq War, for example, personnel of the US army and US Central Intelligence Agency committed a number of human rights violations against detainees in the Abu Ghraib prison,[49] including rape, sodomy, and other forms of sexual abuse.[50][51][52]

Although the risk of sexual misconduct in the armed forces is widely acknowledged, personnel are frequently reluctant to report incidents, typically out of fear of reprisals, according to research in Australia, Canada, France, the UK, and the US.[30][37][42][43][53][54][39]

Women affected by sexual harassment are more likely than other women to suffer stress-related mental illness afterwards.[32] Research in the US found that when sexual abuse of female military personnel is psychiatrically traumatic, the odds of suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after deployment on operations increase by a factor of nine.[31]

Varied behaviors

A man makes an unwanted sexual advance on a woman.

One of the difficulties in understanding sexual harassment is that it involves a range of behaviors. In most cases (although not in all cases) it is difficult for the victim to describe what they experienced. This can be related to difficulty classifying the situation or could be related to stress and humiliation experienced by the recipient. Moreover, behavior and motives vary between individual cases.[55]

Author Martha Langelan describes four different classes of harassers.[56]

- A predatory harasser: a person who gets sexual thrills from humiliating others. This harasser may become involved in sexual extortion, and may frequently harass just to see how targets respond. Those who don't resist may even become targets for rape.

- A dominance harasser: the most common type, who engages in harassing behavior as an ego boost.

- Strategic or territorial harassers who seek to maintain privilege in jobs or physical locations, for example a man's harassment of a female employee in a predominantly male occupation.

- A street harasser: Another type of sexual harassment performed in public places by strangers. Street harassment includes verbal and nonverbal behavior, remarks that are frequently sexual in nature and comment on physical appearance or a person's presence in public.[57]

Prevention

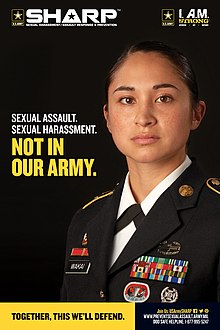

Poster created by the U.S. Army's Sexual Harassment/Assault Response & Prevention (SHARP)

Sexual harassment and assault may be prevented by secondary school,[58] college,[59][60] and workplace education programs.[61] At least one program for fraternity men produced "sustained behavioral change".[59][62]

Many sororities and fraternities in the United States take preventative measures against hazing and hazing activities during the participants' pledging processes (which may often include sexual harassment). Many Greek organizations and universities nationwide have anti-hazing policies that explicitly recognize various acts and examples of hazing, and offer preventative measures for such situations.[63]

Anti-sexual harassment training programs have little evidence of effectiveness and "Some studies suggest that training may in fact backfire, reinforcing gendered stereotypes that place women at a disadvantage".[64]

Impact

The impact of sexual harassment can vary. In research carried out by the EU Fundamental Rights Agency, 17,335 female victims of sexual assault were asked to name the feelings that resulted from the most serious incident of sexual assault that they had encountered since the age of 15. 'Anger, annoyance, and embarrassment were the most common emotional responses, with 45% of women feeling anger, 41% annoyance, and 36% embarrassment. Furthermore, close to one in three women (29%) who has experienced sexual harassment have said that they felt fearful as a result of the most serious incident, while one in five (20%) victims say that the most serious incident made themselves feel ashamed of what had taken place.[65] In other situations, harassment may lead to temporary or prolonged stress or depression depending on the recipient's psychological abilities to cope and the type of harassment and the social support or lack thereof for the recipient. Psychologists and social workers report that severe or chronic sexual harassment can have the same psychological effects as rape or sexual assault.[66][67] Victims who do not submit to harassment may also experience various forms of retaliation, including isolation and bullying.

As an overall social and economic effect every year, sexual harassment deprives women from active social and economic participation and costs hundreds of millions of dollars in lost educational and professional opportunities for mostly girls and women.[68] However, the quantity of men implied in these conflicts is significant.

Coping

Sexual harassment, by definition, is unwanted and not to be tolerated. There are ways, however, for offended and injured people to overcome the resultant psychological effects, remain in or return to society, regain healthy feelings within personal relationships when they were affected by the outside relationship trauma, regain social approval, and recover the ability to concentrate and be productive in educational and work environments. These include stress management and therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy,[69] friends and family support, and advocacy.[70][71]

Immediate psychological and legal counseling are recommended since self-treatment may not release stress or remove trauma, and simply reporting to authorities may not have the desired effect, may be ignored, or may further injure the victim at its response.

A 1991 study done by K.R. Yount found three dominant strategies developed by a sample of women coal miners to manage sexual harassment on the job: the "lady", the "flirt", and the "tomboy".

The "ladies" were typically the older women workers who tended to disengage from the men, kept their distance, avoided using profanity, avoided engaging in any behavior that might be interpreted as suggestive. They also tended to emphasize by their appearance and manners that they were ladies. The consequences for the "ladies" were that they were the targets of the least amount of come-ons, teasing and sexual harassment, but they also accepted the least prestigious and lowest-paid jobs.[72]

The "flirts" were most often the younger single women. As a defense mechanism, they pretended to be flattered when they were the targets of sexual comments. Consequently, they became perceived as the "embodiment of the female stereotype,...as particularly lacking in potential and were given the fewest opportunities to develop job skills and to establish social and self-identities as miners."[72]

The "tomboys" were generally single women, but were older than the "flirts". They attempted to separate themselves from the female stereotype and focused on their status as coal miners and tried to develop a "thick skin". They responded to harassment with humor, comebacks, sexual talk of their own, or reciprocation. As a result, they were often viewed as sluts or sexually promiscuous and as women who violated the sexual double standard. Consequently, they were subjected to intensified and increased harassment by some men. It was not clear whether the tomboy strategy resulted in better or worse job assignments.[72]

The findings of this study may be applicable to other work settings, including factories, restaurants, offices, and universities. The study concludes that individual strategies for coping with sexual harassment are not likely to be effective and may have unexpected negative consequences for the workplace and may even lead to increased sexual harassment. Women who try to deal with sexual harassment on their own, regardless of what they do, seem to be in a no-win situation.[72]

Common effects on the victims

Common psychological, academic, professional, financial, and social effects of sexual harassment and retaliation:

- Becoming publicly sexualized (i.e. groups of people "evaluate" the victim to establish if he or she is "worth" the sexual attention or the risk to the harasser's career)

- Being objectified and humiliated by scrutiny and gossip

- Decreased work or school performance as a result of stress conditions; increased absenteeism in fear of harassment repetition

Defamation of character and reputation- Effects on sexual life and relationships: can put extreme stress upon relationships with significant others, sometimes resulting in divorce

- Firing and refusal for a job opportunity can lead to loss of job or career, loss of income

- Having one's personal life offered up for public scrutiny—the victim becomes the "accused", and his or her dress, lifestyle, and private life will often come under attack.

- Having to drop courses, change academic plans, or leave school (loss of tuition) in fear of harassment repetition or as a result of stress

- Having to relocate to another city, another job, or another school

- Loss of references/recommendations

- Loss of trust in environments similar to where the harassment occurred

- Loss of trust in the types of people that occupy similar positions as the harasser or his or her colleagues, especially in case they are not supportive, difficulties or stress on peer relationships, or relationships with colleagues

- Psychological stress and health impairment

- Weakening of support network, or being ostracized from professional or academic circles (friends, colleagues, or family may distance themselves from the victim, or shun him or her altogether)

Some of the psychological and health effects that can occur in someone who has been sexually harassed as a result of stress and humiliation:

depression; anxiety; panic attacks; sleeplessness; nightmares; shame; guilt; difficulty concentrating; headaches; fatigue; loss of motivation; stomach problems; eating disorders (such as weight loss or gain); alcoholism; feeling betrayed, violated, angry, violent towards the perpetrator, powerless or out of control; increased blood pressure; loss of confidence or self-esteem; withdrawal; isolation; overall loss of trust in people; traumatic stress; post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); complex post-traumatic stress disorder; suicidal thoughts or attempts, and suicide.[73][74][75][76][77]

Post-complaint retaliation and backlash

Retaliation and backlash against a victim are very common, particularly a complainant. Victims who speak out against sexual harassment are often labeled troublemakers who are on their own "power trips", or who are looking for attention. Similar to cases of rape or sexual assault, the victim often becomes the accused, with their appearance, private life, and character likely to fall under intrusive scrutiny and attack.[78] They risk hostility and isolation from colleagues, supervisors, teachers, fellow students, and even friends. They may become the targets of mobbing or relational aggression.[73]

Women are not necessarily sympathetic to female complainants who have been sexually harassed. If the harasser was male, internalized sexism (or jealousy over the sexual attention towards the victim) may encourage some women to react with as much hostility towards the complainant as some male colleagues.[79] Fear of being targeted for harassment or retaliation themselves may also cause some women to respond with hostility.[80] For example, when Lois Jenson filed her lawsuit against Eveleth Taconite Co., the women shunned her both at work and in the community—many of these women later joined her suit.[81] Women may even project hostility onto the victim in order to bond with their male coworkers and build trust.[80]

Retaliation has occurred when a sexual harassment victim suffers a negative action as a result of the harassment. For example, a complainant be given poor evaluations or low grades, have their projects sabotaged, be denied work or academic opportunities, have their work hours cut back, and other actions against them which undermine their productivity, or their ability to advance at work or school, being fired after reporting sexual harassment or leading to unemployment as they may be suspended, asked to resign, or be fired from their jobs altogether. Retaliation can even involve further sexual harassment, and also stalking and cyberstalking of the victim.[79][80] Moreover, a school professor or employer accused of sexual harassment, or who is the colleague of a perpetrator, can use their power to see that a victim is never hired again(blacklisting), or never accepted to another school.

Of the women who have approached her to share their own experiences of being sexually harassed by their teachers, feminist and writer Naomi Wolf wrote in 2004:

I am ashamed of what I tell them: that they should indeed worry about making an accusation because what they fear is likely to come true. Not one of the women I have heard from had an outcome that was not worse for her than silence. One, I recall, was drummed out of the school by peer pressure. Many faced bureaucratic stonewalling. Some women said they lost their academic status as golden girls overnight; grants dried up, letters of recommendation were no longer forthcoming. No one was met with a coherent process that was not weighted against them. Usually, the key decision-makers in the college or university—especially if it was a private university—joined forces to, in effect, collude with the faculty member accused; to protect not him necessarily but the reputation of the university, and to keep information from surfacing in a way that could protect other women. The goal seemed to be not to provide a balanced forum, but damage control.[82]

Another woman who was interviewed by sociologist Helen Watson said, "Facing up to the crime and having to deal with it in public is probably worse than suffering in silence. I found it to be a lot worse than the harassment itself."[83]

Backlash stress

Backlash stress is stress resulting from an uncertainty regarding changing norms for interacting with women in the workplace.[84] Backlash stress now deters many male workers from befriending female colleagues, or providing them with any assistance, such as holding doors open. As a result, women are being handicapped by a lack of the necessary networking and mentorship.[85][86]

Organizational policies and procedures

Most companies have policies against sexual harassment, however these policies are not designed and should not attempt to "regulate romance" which goes against human urges.[87]

Act upon a report of harassment inside the organization should be:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The investigation should be designed to obtain a prompt and thorough collection of the facts, an appropriate responsive action, and an expeditious report to the complainant that the investigation has been concluded, and, to the full extent appropriate, the action taken.

— Mark I. Schickman, Sexual Harassment. The employer's role in prevention. American Bar Association[87]

When organizations do not take the respective satisfactory measures for properly investigating, stress and psychological counseling and guidance, and just deciding of the problem this could lead to:

- Decreased productivity and increased team conflict

- Decreased study or job satisfaction

- Loss of students and staff. Loss of students who leave school and staff resignations to avoid harassment. Resignations and firings of alleged harassers.

- Decreased productivity and increased absenteeism by staff or students experiencing harassment

- Decrease in success at meeting academic and financial goals

- Increased health-care and sick-pay costs because of the health consequences of harassment or retaliation

- The knowledge that harassment is permitted can undermine ethical standards and discipline in the organization in general, as staff or students lose respect for, and trust in, their seniors who indulge in, or turn a blind eye to, or treat improperly sexual harassment

- If the problem is ignored or not treated properly, a company's or school's image can suffer

- High jury awards for the employee, attorney fees and litigation costs if the problem is ignored or not treated properly (in case of firing the victim) when the complainants are advised to and take the issue to court.[16][76][77][88][89][90][91]

Studies show that organizational climate (an organization's tolerance, policy, procedure etc.) and workplace environment are essential for understanding the conditions in which sexual harassment is likely to occur, and the way its victims will be affected (yet, research on specific policy and procedure, and awareness strategies is lacking). Another element which increases the risk for sexual harassment is the job’s gender context (having few women in the close working environment or practicing in a field which is atypical for women).[92]

According to Dr. Orit Kamir, the most effective way to avoid sexual harassment in the workplace, and also influence the public’s state of mind, is for the employer to adopt a clear policy prohibiting sexual harassment and to make it very clear to their employees. Many women prefer to make a complaint and to have the matter resolved within the workplace rather than to "air out the dirty laundry" with a public complaint and be seen as a traitor by colleagues, superiors and employers, adds Kamir.[93][94][95]

Most prefer a pragmatic solution that would stop the harassment and prevent future contact with the harasser rather than turning to the police. More about the difficulty in turning an offense into a legal act can be found in Felstiner & Sarat's (1981) study,[96] which describes three steps a victim (of any dispute) must go through before turning to the justice system: naming – giving the assault a definition, blaming – understanding who is responsible for the violation of rights and facing them, and finally, claiming – turning to the authorities.

Evolution of law in different jurisdictions

It may include a range of actions from mild transgressions to sexual abuse or sexual assault.[97] Sexual harassment is a form of illegal employment discrimination in many countries, and is a form of abuse (sexual and psychological abuses) and bullying.

The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women classifies violence against women into three categories: that occurring in the family, that occurring within the general community, and that perpetrated or condoned by the State. The term sexual harassment is used in defining violence occurring in the general community, which is defined as: "Physical, sexual and psychological violence occurring within the general community, including rape, sexual abuse, sexual harassment and intimidation at work, in educational institutions and elsewhere, trafficking in women and forced prostitution."[98]

Sexual harassment is subject to a directive in the European Union.[99] The United States' Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) states, "It is unlawful to harass a person (an applicant or employee) because of that person's sex."

In India, the case of Vishakha and others v State of Rajasthan in 1997 has been credited with establishing sexual harassment as illegal.[100] In Israel, the 1988 Equal Employment Opportunity Law made it a crime for an employer to retaliate against an employee who had rejected sexual advances, but it wasn't until 1998 that the Israeli Sexual Harassment Law made such behavior illegal.[101]

In May 2002, the European Union Council and Parliament amended a 1976 Council Directive on the equal treatment of men and women in employment to prohibit sexual harassment in the workplace, naming it a form of sex discrimination and violation of dignity. This Directive required all Member States of the European Union to adopt laws on sexual harassment, or amend existing laws to comply with the Directive by October 2005.[102]

In 2005, China added new provisions to the Law on Women's Right Protection to include sexual harassment.[103] In 2006, "The Shanghai Supplement" was drafted to help further define sexual harassment in China.[104]

Sexual harassment was specifically criminalized for the first time in modern Egyptian history in June 2014.[105]

Sexual harassment remains legal in Kuwait[106] and Djibouti.[107]

Varied legal guidelines and definitions

The United Nations General Recommendation 19 to the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women defines sexual harassment of women to include:

such unwelcome sexually determined behavior as physical contact and advances, sexually colored remarks, showing pornography and sexual demands, whether by words or actions. Such conduct can be humiliating and may constitute a health and safety problem; it is discriminatory when the woman has reasonable ground to believe that her objection would disadvantage her in connection with her employment, including recruitment or promotion, or when it creates a hostile working environment.

While such conduct can be harassment of women by men, many laws around the world which prohibit sexual harassment recognize that both men and women may be harassers or victims of sexual harassment. However, most claims of sexual harassment are made by women.[108]

There are many similarities, and also important differences in laws and definitions used around the world.

Africa

Morocco

In 2016 a stricter law proscribing sexual harassment was proposed in Morocco specifying fines and a possible jail sentence of up to 6 months.[109] The existing law against harassment was reported to not be upheld, as harassment was not reported to police by victims and even when reported, was not investigated by police or prosecuted by the courts.[109][110]

Australia

The Sex Discrimination Act 1984 defines sexual harassment as "... a person sexually harasses another person (the person harassed ) if: (a) the person makes an unwelcome sexual advance, or an unwelcome request for sexual favours, to the person harassed; or (b) engages in other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature in relation to the person harassed; in circumstances in which a reasonable person, having regard to all the circumstances, would have anticipated the possibility that the person harassed would be offended, humiliated or intimidated."[111]

Europe

In the European Union, there is a directive on sexual harassment. The Directive 2002/73/EC - equal treatment of 23 September 2002 amending Council Directive 76/207/EEC on the implementation of the principle of equal treatment for men and women as regards access to employment, vocational training and promotion, and working conditions states:[99]

For the purposes of this Directive, the following definitions shall apply: (...)

- sexual harassment: where any form of unwanted verbal, non-verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature occurs, with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a person, in particular when creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment

Harassment and sexual harassment within the meaning of this Directive shall be deemed to be discrimination on the grounds of sex and therefore prohibited.

The Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence also addresses the issue of sexual harassment (Article 40), using a similar definition.[112]

Denmark

Sexual harassment is defined as, when any verbal, non-verbal or physical action is used to change a victim's sexual status against the will of the victim and resulting in the victim feeling inferior or hurting the victim's dignity. Man and woman are looked upon as equal, and any action trying to change the balance in status with the differences in sex as a tool, is also sexual harassment. In the workplace, jokes, remarks, etc., are only deemed discriminatory if the employer has stated so in their written policy. Law number 1385 of December 21, 2005 regulates this area.[113]

France

In France, both the Criminal Code and the Labor Code are relevant to the issue of sexual harassment. Until May 4, 2012, article 222-33 of the French Criminal Code described sexual harassment as "The fact of harassing anyone in order to obtain favors of a sexual nature".[114] Since 2002, it recognized the possibility of sexual harassment between co-workers and not only by supervisors. On May 4, 2012, the Conseil constitutionnel (French Supreme Court) quashed the definition of the criminal code as being too vague.[115] The 2012 decision resulted from a law on priority preliminary rulings on the issue of constitutionality. As a consequence of this decision, all pending procedures before criminal courts were cancelled. Several feminist NGOs, such as AFVT, criticized this decision. President François Hollande, the Minister of Justice (Christine Taubira) and the Minister of Equality (Najat Belkacem) asked that a new law be voted rapidly. As a result, LOI n°2012-954 du 6 août 2012 was voted in, providing a new definition.[116] In addition to criminal provisions, the French Labor code also prohibits sexual harassment.[117] The legislator voted a law in 2008[118] that copied the 2002/73/EC Directive[119] definition without modifying the French Labour Code.

Germany

Sexual harassment is no statutory offense in Germany. In special cases it might be chargeable as "Insult" (with sexual context) as per § 185 Strafgesetzbuch but only if special circumstances show an insulting nature.

The victim has only a right to self-defend while the attack takes place. If a perpetrator kisses or gropes the victim, they may only fight back while this is happening. If the victim would, for instance, slap back after the attacker already stopped, the victim might be chargeable for assault as per § 223 Strafgesetzbuch.[120]

In June 2016 the governing coalition decided about the key points of a tightening of the law governing sexual offenses (Sexualstrafrecht, literally: law on the punishment of sexual delicts). At July 7, 2016 the Bundestag passed the resolution[121] and by autumn 2016 the draft bill will be presented to the second chamber, the Bundesrat.[122] By this change, sexual harassment shall become punishable under the Sexualstrafrecht.[123]

Greece

In response to the EU Directive 2002/73/EC, Greece enacted Law 3488/2006 (O.G.A.'.191). The law specifies that sexual harassment is a form of gender-based discrimination in the workplace. Victims also have the right to compensation.[124] Prior to this law, the policy on sexual harassment in Greece was very weak. Sexual harassment was not defined by any law, and victims could only use general laws, which were very poor in addressing the issue.[125][126]

Russia

In the Criminal Code, Russian Federation, (CC RF), there exists a law which prohibits utilization of an office position and material dependence for coercion of sexual interactions (Article 118, current CC RF). However, according to the Moscow Center for Gender Studies, in practice, the courts do not examine these issues.[127]

The Daily Telegraph quotes a survey in which "100 percent of female professionals [in Russia] said they had been subjected to sexual harassment by their bosses, 32 per cent said they had had intercourse with them at least once and another seven per cent claimed to have been raped."[128]

Switzerland

A ban on discrimination was included in the Federal Constitution (Article 4, Paragraph 2 of the old Federal Constitution) in 1981 and adopted in Article 8, paragraph 2 of the revised Constitution. The ban on sexual harassment in the workplace forms part of the Federal Act on Gender Equality (GEA) of 24 March 1995, where it is one of several provisions which prohibit discrimination in employment and which are intended to promote equality. Article 4 of the GEA defines the circumstances, Article 5 legal rights and Article 10 protection against dismissal during the complaints procedure.[129] Article 328, paragraph 1 of the Code of Obligations (OR), Article 198 (2) of the Penal Code (StGB) and Article 6, paragraph 1 of the Employment Act (ArG) contain further statutory provisions on the ban on sexual harassment. The ban on sexual harassment is intended exclusively for employers, within the scope of their responsibility for protection of legal personality, mental and physical well-being and health.[citation needed]

Article 4 of the GEA of 1995 discusses the topic of sexual harassment in the workplace: "Any harassing behaviour of a sexual nature or other behaviour related to the person's sex that adversely affects the dignity of women or men in the workplace is discriminatory. Such behaviour includes in particular threats, the promise of advantages, the use of coercion and the exertion of pressure in order to obtain favours of a sexual nature."[129]

United Kingdom

The Discrimination Act of 1975, was modified to establish sexual harassment as a form of discrimination in 1986.[130] It states that harassment occurs where there is unwanted conduct on the ground of a person's sex or unwanted conduct of a sexual nature and that conduct has the purpose or effect of violating a person's dignity, or of creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for them. If an employer treats someone less favourably because they have rejected, or submitted to, either form of harassment described above, this is also harassment.[131]

Asia

India

Sexual harassment in India is termed "Eve teasing" and is described as: unwelcome sexual gesture or behaviour whether directly or indirectly as sexually coloured remarks; physical contact and advances; showing pornography; a demand or request for sexual favours; any other unwelcome physical, verbal or non-verbal conduct being sexual in nature or passing sexually offensive and unacceptable remarks. The critical factor is the unwelcomeness of the behaviour, thereby making the impact of such actions on the recipient more relevant rather than intent of the perpetrator.[100] According to the Indian constitution, sexual harassment infringes the fundamental right of a woman to gender equality under Article 14 and her right to life and live with dignity under Article 21.[132]

In 1997, the Supreme Court of India in a Public Interest Litigation, defined sexual harassment at workplace, preventive measures and redress mechanism. The judgment is popularly known as Vishaka Judgment.[133] In April 2013, India enacted its own law on sexual harassment in the workplace - The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013. Almost 16 years after the Supreme Court's landmark guidelines on prevention of sexual harassment in the workplace (known as the "Vishaka Guidelines"), the Act has endorsed many of the guidelines, and is a step towards codifying gender equality. The Act is intended to include all women employees in its ambit, including those employed in the unorganized sector, as well as domestic workers.

The Act has identified sexual harassment as a violation of the fundamental rights of a woman to equality under articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution of India and her right to life and to live with dignity under article 21 of the Constitution; as well as the right to practice any profession or to carry on any occupation, trade or business which includes a right to a safe environment free from sexual harassment. The Act also states that the protection against sexual harassment and the right to work with dignity are universally recognized human rights by international conventions and instruments such as Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women, which has been ratified on the 25th June, 1993 by the Government of India.[134]

The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 introduced changes to the Indian Penal Code, making sexual harassment an expressed offense under Section 354 A, which is punishable up to three years of imprisonment and or with fine. The Amendment also introduced new sections making acts like disrobing a woman without consent, stalking and sexual acts by person in authority an offense.

Israel

The 1998 Israeli Sexual Harassment Law interprets sexual harassment broadly, and prohibits the behavior as a discriminatory practice, a restriction of liberty, an offense to human dignity, a violation of every person's right to elementary respect, and an infringement of the right to privacy. Additionally, the law prohibits intimidation or retaliation thus related to sexual harassment are defined by the law as "prejudicial treatment".[101]

Japan

Public sign in Chiba, Japan warning of chikan

Sexual Harassment, or sekuhara in Japanese, appeared most dramatically in Japanese discourse in 1989, when a court case in Fukuoka ruled in favor of a woman who had been subjected to the spreading of sexual rumors by a co-worker. When the case was first reported, it spawned a flurry of public interest: 10 books were published, including English-language feminist guidebooks to ‘how not to harass women’ texts for men.[135] Sekuhara was named 1989’s ‘Word of the Year.’ The case was resolved in the victim’s favor in 1992, awarding her about $13,000 in damages, the first sexual harassment lawsuit in Japanese history.[136]

Laws then established two forms of sexual harassment: daisho, in which rewards or penalties are explicitly linked to sexual acts, and kankyo, in which the environment is made unpleasant through sexual talk or jokes, touching, or hanging sexually explicit posters. This applies to everyone in an office, including customers.[135]

Pakistan

Pakistan has promulgated harassment law in 2010 with nomenclature as "The Protection Against Harassment of Women at The Workplace Act, 2010".

This law defines the act of harassment in following terms.

"Harassment means any unwelcome sexual advance, request for sexual favors or other verbal or written communication or physical conduct of a sexual nature or sexually demeaning attitude, causing interference with work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment, or the attempt to punish the complainant for refusal to such a request or is made a condition for employment."

Pakistan has adopted a Code of Conduct for Gender Justice in the Workplace that will deal with cases of sexual harassment. The Alliance Against Sexual Harassment At workplace (AASHA) announced they would be working with the committee to establish guidelines for the proceedings. AASHA defines sexual harassment much the same as it is defined in the U.S. and other cultures.[137]

Philippines

The Anti-Sexual Harassment Act of 1995 was enacted:

primarily to protect and respect the dignity of workers, employees, and applicants for employment as well as students in educational institutions or training centers. This law, consisting of ten sections, provides for a clear definition of work, education or training-related sexual harassment and specifies the acts constituting sexual harassment. It likewise provides for the duties and liabilities of the employer in cases of sexual harassment, and sets penalties for violations of its provisions. It is to be noted that a victim of sexual harassment is not barred from filing a separate and independent action for damages and other relief aside from filing the charge for sexual harassment.[138]

United States

Evolution of sexual harassment law

Workplace

In the US, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination based on race, sex, color, national origin or religion. Initially only intended to combat sexual harassment of women, {42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2} the prohibition of sex discrimination covers both females and males. This discrimination occurs when the sex of the worker is made as a condition of employment (i.e. all female waitpersons or male carpenters) or where this is a job requirement that does not mention sex but ends up preventing many more persons of one sex than the other from the job (such as height and weight limits). This act only applies to employers with 15 or more employees.[139]

Barnes v. Train (1974) is commonly viewed as the first sexual harassment case in America, even though the term "sexual harassment" was not used.[140] The term "sexual harassment" was coined and popularized by Lin Farley in 1975, based on a pattern she recognized during a 1974 Cornell University class she taught on women and work.[141] In 1976, Williams v. Saxbe established sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination when sexual advances by a male supervisor towards a female employee, if proven, would be deemed an artificial barrier to employment placed before one gender and not another. In 1980 the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) issued regulations defining sexual harassment and stating it was a form of sex discrimination prohibited by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the 1986 case of Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, the Supreme Court first recognized "sexual harassment" as a violation of Title VII, established the standards for analyzing whether the conduct was welcome and levels of employer liability, and that speech or conduct in itself can create a "hostile environment".[142] This case filed by Mechelle Vinson ruled that the sexual conduct between the subordinate and supervisor could not be deemed voluntary due to the hierarchical relationship between the two positions in the workplace.[143] Following the ruling of Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, reported sexual harassment cases grew from 10 cases being registered by the EEOC per year before 1986 to 624 case being reported in the subsequent following year.[144] This number of reported cases to the EEOC rose to 2,217 in 1990 and then 4,626 by 1995.[144]

The Civil Rights Act of 1991 added provisions to Title VII protections including expanding the rights of women to sue and collect compensatory and punitive damages for sexual discrimination or harassment, and the case of Ellison v. Brady resulted in rejecting the reasonable person standard in favor of the "reasonable woman standard" which allowed for cases to be analyzed from the perspective of the complainant and not the defendant.[145] Also in 1991, Jenson v. Eveleth Taconite Co. became the first sexual harassment case to be given class action status paving the way for others. Seven years later, in 1998, through that same case, new precedents were established that increased the limits on the "discovery" process in sexual harassment cases, that then allowed psychological injuries from the litigation process to be included in assessing damages awards. In the same year, the courts concluded in Faragher v. City of Boca Raton, Florida, and Burlington v. Ellerth, that employers are liable for harassment by their employees.[146][147] Moreover, Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services set the precedent for same-sex harassment, and sexual harassment without motivation of "sexual desire", stating that any discrimination based on sex is actionable so long as it places the victim in an objectively disadvantageous working condition, regardless of the gender of either the victim, or the harasser.

In the 2006 case of Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railway Co. v. White, the standard for retaliation against a sexual harassment complainant was revised to include any adverse employment decision or treatment that would be likely to dissuade a "reasonable worker" from making or supporting a charge of discrimination.

During 2007 alone, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and related state agencies received 12,510 new charges of sexual harassment on the job.[148]

The 2010 case, Reeves v. C.H. Robinson Worldwide, Inc. ruled that a hostile work environment can be created in a workplace where sexually explicit language and pornography are present. A hostile workplace may exist even if it is not targeted at any particular employee.[149]

From 2010 through 2016, approximately 17% of sexual harassment complaints filed with the EEOC were made by men.[150]

Education

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (United States) states "No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance."

In Franklin v. Gwinnett County Public Schools (1992), the U.S. Supreme Court held that private citizens could collect damage awards when teachers sexually harassed their students.[151] In Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986) the courts ruled that schools have the power to discipline students if they use "obscene, profane language or gestures" which could be viewed as substantially interfering with the educational process, and inconsistent with the "fundamental values of public school education."[152] Under regulations issued in 1997 by the U.S. Department of Education, which administers Title IX, school districts should be held responsible for harassment by educators if the harasser "was aided in carrying out the sexual harassment of students by his or her position of authority with the institution."[153] In Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, and Murrell v. School Dist. No. 1, 1999, schools were assigned liability for peer-to-peer sexual harassment if the plaintiff sufficiently demonstrated that the administration's response shows "deliberate indifference" to "actual knowledge" of discrimination.[154][155]

Additionally

There are a number of legal options for a complainant in the U.S.: mediation, filing with the EEOC or filing a claim under a state Fair Employment Practices (FEP) statute (both are for workplace sexual harassment), filing a common law tort, etc.[156] Not all sexual harassment will be considered severe enough to form the basis for a legal claim. However, most often there are several types of harassing behaviors present, and there is no minimum level for harassing conduct under the law.[68] The section below "EEOC Definition" describes the legal definitions that have been created for sexual harassment in the workplace. Definitions similar to the EEOC definition have been created for academic environments in the U.S. Department of Education Sexual Harassment Guidance.[157]

EEOC Definition

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission claims that it is unlawful to harass an applicant or employee of any sex in the workplace. The harassment could include sexual harassment. The EEOC says that the victim and harasser could be any gender and that the other does not have to be of the opposite sex. The law does not ban offhand comments, simple teasing, or incidents that aren't very serious. If the harassment gets to the point where it creates a harsh work environment, it will be taken care of.[3] In 1980, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission produced a set of guidelines for defining and enforcing Title VII (in 1984 it was expanded to include educational institutions). The EEOC defines sexual harassment as:

Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, or other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature when:

- Submission to such conduct was made either explicitly or implicitly a term or condition of an individual's employment,

- Submission to or rejection of such conduct by an individual was used as the basis for employment decisions affecting such individual, or

- Such conduct has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual's work performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working environment.

1. and 2. are called "quid pro quo" (Latin for "this for that" or "something for something"). They are essentially "sexual bribery", or promising of benefits, and "sexual coercion".

Type 3. known as "hostile work environment", is by far the most common form. This form is less clear cut and is more subjective.[79]

Note: a workplace harassment complainant must file with the EEOC and receive a "right to sue" clearance, before they can file a lawsuit against a company in federal court.[68]

Quid pro quo sexual harassment

International Trade Union Confederation (2015-2017).

Quid pro quo means "this for that". In the workplace, this occurs when a job benefit is directly tied to an employee submitting to unwelcome sexual advances. For example, a supervisor promises an employee a raise if he or she will go out on a date with him or her, or tells an employee he or she will be fired if he or she doesn't sleep with him or her.[158] Quid pro quo harassment also occurs when an employee makes an evaluative decision, or provides or withholds professional opportunities based on another employee's submission to verbal, nonverbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature. Quid pro quo harassment is equally unlawful whether the victim resists and suffers the threatened harm or submits and thus avoids the threatened harm.[159]

Hostile environment sexual harassment

This occurs when an employee is subjected to comments of a sexual nature, unwelcome physical contact, or offensive sexual materials as a regular part of the work environment. For the most part, a single isolated incident will not be enough to prove hostile environment harassment unless it involves extremely outrageous and egregious conduct. The courts will try to decide whether the conduct is both "serious" and "frequent." Supervisors, managers, co-workers and even customers can be responsible for creating a hostile environment.[160]

The line between "quid pro quo" and "hostile environment" harassment is not always clear and the two forms of harassment often occur together. For example, an employee's job conditions are affected when a sexually hostile work environment results in a constructive discharge. At the same time, a supervisor who makes sexual advances toward a subordinate employee may communicate an implicit threat to retaliate against her if she does not comply.[161]

"Hostile environment" harassment may acquire characteristics of "quid pro quo" harassment if the offending supervisor abuses his authority over employment decisions to force the victim to endure or participate in the sexual conduct. Sexual harassment may culminate in a retaliatory discharge if a victim tells the harasser or her employer she will no longer submit to the harassment, and is then fired in retaliation for this protest. Under these circumstances it would be appropriate to conclude that both harassment and retaliation in violation of section 704(a) of Title VII have occurred."

Sexual orientation discrimination

In the United States, there are no federal laws prohibiting discrimination against employees based on their sexual orientation. However, Executive Order 13087, signed by President Bill Clinton, outlaws discrimination based on sexual orientation against federal government employees. If a small business owner owns his or her business in a state where there is a law against sexual orientation discrimination, the owner must abide to the law regardless of there not being a federal law. Twenty states and the District of Columbia have laws against this form of discrimination in the workplace. These states include California, Connecticut, Colorado, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin.[162] For example, California has laws in place to protect employees who may have been discriminated against based upon sexual orientation or perceived sexual orientation. California law prohibits discrimination against those "with traits not stereotypically associated with their gender", such as mannerisms, appearance, or speech. Sexual orientation discrimination comes up, for instance, when employers enforce a dress code, permit women to wear makeup but not men, or require men and women to only use restrooms designated for their particular sex regardless of whether they are transgender.

Retaliation

Retaliation has occurred when an employee suffers a negative action after he or she has made a report of sexual harassment, file a grievance, assist someone else with a complaint, or participate in discrimination prevention activities. Negative actions can include being fired, demotion, suspension, denial of promotion, poor evaluation, unfavorable job reassignment—any adverse employment decision or treatment that would be likely to dissuade a "reasonable worker" from making or supporting a charge of discrimination. (See Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railway Co. v. White.)[163] Retaliation is as illegal as the sexual harassment itself, but also as difficult to prove. Also, retaliation is illegal even if the original charge of sexual harassment was not proven.

Historical antecedents

Ancient Rome

In ancient Rome, according to Bruce W. Frier and Thomas A.J. McGinn, what is now called sexual harassment[164] was then any of accosting, stalking, and abducting. Accosting was "harassment through attempted seduction"[164] or "assault[ing] another's chastity with smooth talk ... contrary to good morals",[164] which was more than the lesser offense(s) of "obscene speech, dirty jokes, and the like",[164] "foul language",[164] and "clamor",[164] with the accosting of "respectable young girls" who however were dressed in slaves' clothing being a lesser offense[164] and the accosting of "women ... dressed as prostitutes" being an even lesser offense.[164]Stalking was "silently, persistently pursuing"[164] if it was "contrary to good morals",[165] because a pursuer's "ceaseless presence virtually ensures appreciable disrepute".[164]Abducting an attendant, who was someone who follows someone else as a companion and could be a slave,[166] was "successfully forcing or persuading the attendant to leave the side of the intended target",[166] but abducting while the woman "has not been wearing respectable clothing" was a lesser offense.[164]

Criticism

Though the phrase sexual harassment is generally acknowledged to include clearly damaging and morally deplorable behavior, its boundaries can be broad and controversial. Accordingly, misunderstandings can occur. In the US, sexual harassment law has been criticized by persons such as the criminal defense lawyer Alan Dershowitz and the legal writer and libertarian Eugene Volokh, for imposing limits on the right to free speech.[167]

Jana Rave, professor in organizational studies at the Queen's School of Business, criticized sexual harassment policy in the Ottawa Business Journal as helping maintain archaic stereotypes of women as "delicate, asexual creatures" who require special protection when at the same time complaints are lowering company profits.[89]Camille Paglia says that young girls can end up acting in such ways as to make sexual harassment easier, such that for example, by acting "nice" they can become a target. Paglia commented in an interview with Playboy, "Realize the degree to which your niceness may invoke people to say lewd and pornographic things to you--sometimes to violate your niceness. The more you blush, the more people want to do it."[168]

Other critics assert that sexual harassment is a very serious problem, but current views focus too heavily on sexuality rather than on the type of conduct that undermines the ability of women or men to work together effectively. Viki Shultz, a law professor at Yale University comments, "Many of the most prevalent forms of harassment are designed to maintain work—particularly the more highly rewarded lines of work—as bastions of male competence and authority."[169] Feminist Jane Gallop sees this evolution of the definition of sexual harassment as coming from a "split" between what she calls "power feminists" who are pro-sex (like herself) and what she calls "victim feminists", who are not. She argues that the split has helped lead to a perversion of the definition of sexual harassment, which used to be about sexism but has come to be about anything that's sexual.[170]

There is also concern over abuses of sexual harassment policy by individuals as well as by employers and administrators using false or frivolous accusations as a way of expelling employees they want to eliminate for other reasons. These employees often have virtually no recourse thanks to the at-will law in most US states.[171]

O'Donohue and Bowers outlined 14 possible pathways to false allegations of sexual harassment: "lying, borderline personality disorder, histrionic personality disorder, psychosis, gender prejudice, substance abuse, dementia, false memories, false interpretations, biased interviews, sociopathy, personality disorders not otherwise specified."[172]

There is also discussion of whether some recent trends towards more revealing clothing and permissive habits have created a more sexualized general environment, in which some forms of communication are unfairly labeled harassment, but are simply a reaction to greater sexualization in everyday environments.[173]

There are many debates about how organizations should deal with sexual harassment. Some observers feel strongly that organizations should be held to a zero tolerance standard of "Must report - must investigate - must punish."

Others write that those who feel harassed should in most circumstances have a choice of options.[94][95][174]

In media and literature

678, a film focusing on the sexual harassment of women in Egypt

The Ballad of Little Jo, a film based on the true story of a woman living in the frontier west who disguises herself as a man to protect herself from the sexual harassment and abuse of women all too common in that environment

Disclosure, a film starring Michael Douglas and Demi Moore in which a man is sexually harassed by his female superior, who tries to use the situation to destroy his career by claiming that he was the sexual harasser

Disgrace, a novel about a South African literature professor whose career is ruined after he has an affair with a student.

Hostile Advances: The Kerry Ellison Story: television movie about Ellison v. Brady, the case that set the "reasonable woman" precedent in sexual harassment law

In the Company of Men, a film about two male coworkers who, angry at women, plot to seduce and maliciously toy with the emotions of a deaf subordinate who works at the same company

Les Miserables, a novel by Victor Hugo. The character Fantine is fired from her job after refusing to have sex with her supervisor.

The Magdalene Sisters, a film based on the true stories of young women imprisoned for "bringing shame upon their families" by being raped, sexually abused, flirting, or simply being pretty, and subsequently subjected to sexual harassment and abuse by the nuns and priests in the Magdalene asylums in Ireland.

Nine to Five, a comedy film starring Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton, about three women who are subjected to constant bullying and sexual harassment by their boss

North Country, a 2005 film depicting a fictionalized account of Jenson v. Eveleth Taconite Co., the first sexual harassment class action lawsuit in the US.

Oleanna, an American play by David Mamet, later a film starring William H. Macy. A college professor is accused of sexual harassment by a student. The film deals with the moral controversy as it never becomes clear which character is correct.

Pretty Persuasion, a film starring Evan Rachel Wood and James Woods in which students turn the tables on a lecherous and bigoted teacher. A scathingly satirical film of sexual harassment and discrimination in schools, and attitudes towards females in media and society.

War Zone, a documentary about street harassment- "Sexual Harassment Panda", an episode of South Park that parodies sexual harassment in schools and the lawsuits which result from lawyers and children using the vague definition of sexual harassment in order to win their lawsuits

- "Sexual Harassment In The Workplace", an instrumental minor-key blues song by Frank Zappa, from the album Guitar

Hunters Moon, a novel by Karen Robards, deals with a female's experience of sexual harassment in the workplace- In the pilot episode of the US comedy series Ally McBeal, Ally leaves her job at her first firm because of unwanted attention and groping from a male co-worker

- The 1961 musical How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying deals with themes of both consensual office romance and unwelcome sexual harassment; one man is fired for making a pass at the wrong woman, and another man is warned via a song called A Secretary is Not a Toy.

- The Fox television musical-drama show Glee deals with issues around sexual harassment in the episodes "The Power of Madonna", "Never Been Kissed' and "The First Time".

- Commander Jeffrey Gordon, a military spokesman in Guantanamo, complained that a reporter had been sexually harassing him.

- The AMC drama show Mad Men, set in the 1960s, explores the extent to which sexual harassment was prevalent in society during that time.

See also

- Catharine MacKinnon

- Disciplinary counseling

- Employment discrimination

- Hostile environment sexual harassment

- Hostile work environment

- Initiatives to prevent sexual violence

- London Anti-Street Harassment campaign

- Love contract

- Microinequity

- Mass sexual assault

- #MeToo

- Occupational health psychology

- Operation Anti Sexual Harassment

- Posttraumatic stress disorder

- Psychological stress

- Sexism

- Sexual abuse

- Sexual assault

- Sexual bullying

- Sexual harassment in education

- Sexual harassment in the military

- Stalking

- Sexual harassment in the workplace in the United States

- Til It Happens To You

- Workplace bullying

- Workplace harassment

- Workplace stress

Notes

^ Paludi, Michele A.; Barickman, Richard B. (1991). "Definitions and incidence of academic and workplace sexual harassment". Academic and workplace sexual harassment: a resource manual. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. pp. 2–5. ISBN 9780791408308..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Dziech, Billie Wright; Weiner, Linda. The Lecherous Professor: Sexual Harassment on Campus.[page needed] Chicago Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1990.

ISBN 978-0-8070-3100-1; Boland, 2002[page needed]

^ abc "Sexual Harassment". U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

^ Text of Oncale v.Sundowner Offshore Services, Inc., 528 U.S. 75 (1998) is available from: Findlaw Justia

^ ab "MacKinnon, Catharine A. - University of Michigan Law School". www.law.umich.edu. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

^ Kamberi, Ferdi; Gollopeni, Besim (2015-12-01). "The Phenomenon of Sexual Harassment at the Workplace in Republic of Kosovo". International Review of Social Sciences. 3: 13.

^ Rowe, Mary, "Saturn's Rings," a study of the minutiae of sexism which maintain discrimination and inhibit affirmative action results in corporations and non-profit institutions; published in Graduate and Professional Education of Women, American Association of University Women, 1974, pp. 1–9. "Saturn's Rings II" is a 1975 updating of the original, with racist and sexist incidents from 1974 and 1975. Revised and republished as "The Minutiae of Discrimination: The Need for Support," in Forisha, Barbara and Barbara Goldman, Outsiders on the Inside, Women in Organizations, Prentice-Hall, Inc., New Jersey, 1981, Ch. 11, pp. 155–171.

ISBN 978-0-13-645382-6.

^ "Groping in the Ivy League led to the first sexual harassment suit—and nothing happened to the man". Timeline. 2017-10-20. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

^ Altschuler, Glenn C.; Kramnick, Isaac (2014-08-12). Cornell: A History, 1940–2015. Cornell University Press. p. 146. ISBN 9780801471889.

^ Brownmiller, Susan. In Our Time: Memoir of a Revolution. p. 281.

^ MacKinnon, Catharine (1979). Sexual Harassment of Working Women: A Case of Sex Discrimination. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300022995.

^ Lipsitz, Raina (2017-10-20). "Sexual Harassment Law Was Shaped by the Battles of Black Women". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 2018-04-12.

^ Baker, Carrie N. (2008). The Women's Movement Against Sexual Harassment. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521879354.

^ Lipsitz, Raina (2017-10-20). "Sexual Harassment Law Was Shaped by the Battles of Black Women". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 2018-04-10.

^ "#HerToo: 40 Years Ago This Woman Helped Make Sexual Harassment Illegal". Washingtonian. 2018-03-04. Retrieved 2018-04-10.

^ abc Bowers, Toni; Hook, Brian. Hostile work environment: A manager's legal liability, Tech Republic. October 22, 2002. Retrieved on March 3, 2012.

^ Philips, Chuck (April 18, 1993). ""You've Still Got a Long Way to Go, Baby," April 18". LA Times. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

^ Becklund Philips, Laurie Chuck (November 3, 1991). "Sexual Harassment Claims Confront Music Industry: Bias: Three record companies and a law firm have had to cope with allegations of misconduct by executives". LA Times. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

^ Philips, Chuck (March 5, 1992). "'Anita Hill of Music Industry' Talks : * Pop music: Penny Muck, a secretary whose lawsuit against Geffen Records sparked a debate about sexual harassment in the music business, speaks out in her first extended interview". LA Times. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

^ Philips, Chuck (November 17, 1992). "Geffen Firm Said to Settle Case of Sex Harassment : Litigation: An out-of-court settlement of $500,000 is reportedly reached in one suit, but another may be filed". LA Times. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

^ Philips, Chuck (July 21, 1992). "Controversial Record Exec Hired by Def". LA Times. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

^ Laursen, Patti (May 3, 1993). "Women in Music". LA Times. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

^ Barnet, Richard; Burriss, Larry; Fischer, Paul (September 30, 2001). Controversies in the music business. Greenwood. pp. 112–114. ISBN 978-0313310942.

^ "Reporting of violence against women in University. [Social Impact]. VGU. Gender-based Violence in Spanish Universities (2006-2008)". SIOR, Social Impact Open Repository.

^ Heyman, Richard (1994). Why Didn't You Say That in the First Place? San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

ISBN 978-0-7879-0344-2.[page needed]

^ Duggan, Maeve "Online Harassment", PEW Research Center, 2014.

^ "EEOC Home Page". www.eeoc.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

^ "Research & Reports". www.sapr.mil. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

^ "Know Your Rights: Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964". AAUW: Empowering Women Since 1881. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

^ abc British army (2015). "Sexual harassment report 2015" (PDF). gov.uk. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

^ ab Anderson, E H; Suris, A (2013). "Military sexual trauma". In Moore, Brett A; Barnett, Jeffrey E. Military psychologists' desk reference. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 264–269. ISBN 9780199928262. OCLC 828143812.

^ ab Watkins, Kimberley; Bennett, Rachel; Richer, Isabelle; Zamorski, Mark. "Sexual Assault in the Canadian Armed Forces: Prevalence, Circumstances, Correlates, and Mental Health Associations" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-03-08.

^ Gallagher, Kathryn E.; Parrott, Dominic J. (May 2011). "What accounts for men's hostile attitudes toward women? The influence of hegemonic male role norms and masculine gender role stress". Violence Against Women. 17 (5): 568–583. doi:10.1177/1077801211407296. PMC 3143459. PMID 21531691.

^ Parrott, Dominic J.; Zeichner, Amos (2003). "Effects of hypermasculinity oh physical aggression against women". Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 4 (1): 70–78. doi:10.1037/1524-9220.4.1.70.

^ Rosen, Leora N; et al. (September 2003). "The Effects of Peer Group Climate on Intimate Partner Violence among Married Male U.S. Army Soldiers". Violence Against Women. 9 (9): 1045–1071. doi:10.1177/1077801203255504.

^ Baugher, Amy R.; Gazmararian, Julie A. (2015). "Masculine gender role stress and violence: A literature review and future directions". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 24: 107–112. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2015.04.002.

^ ab Deschamps, Marie (2015). "External Review into Sexual Misconduct and Sexual Harassment in the Canadian Armed Forces" (PDF). forces.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

^ ab Watkins, Kimberley; Bennett, Rachel; Richer, Isabelle; Zamorski, Mark. "Sexual Assault in the Canadian Armed Forces: Prevalence, Circumstances, Correlates, and Mental Health Associations" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-03-08.

^ ab Leila, Miñano; Pascual, Julia (2014). La guerre invisible: révélations sur les violences sexuelles dans l'armée française (in French). Paris: Les Arènes. ISBN 978-2352043027. OCLC 871236655.