Tatlin's Tower

| Monument to the Third International | |

|---|---|

Памятник III Интернационалу | |

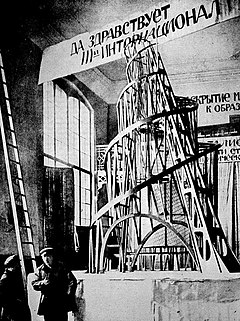

Vladimir Tatlin and a model of his Monument to the Third International, Moscow, 1920. | |

| Alternative names | Tatlin's Tower |

| General information | |

| Status | Never built |

| Type | Monument, Communications, Conferences, Government, etc. |

| Architectural style | Constructivism |

| Location | St. Petersburg, Russia |

| Construction started | Never |

| Height | 400 m (1,300 ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Vladimir Tatlin |

| Architecture firm | Creative Collective |

Tatlin’s Tower, or the project for the Monument to the Third International (1919–20),[1] was a design for a grand monumental building by the Russian artist and architect Vladimir Tatlin, that was never built.[2] It was planned to be erected in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, as the headquarters and monument of the Comintern (the Third International).

Contents

1 Plans

2 Evaluations

3 Models

4 See also

5 References and sources

6 External links

Plans

Tatlin's Constructivist tower was to be built from industrial materials: iron, glass and steel. In materials, shape and function, it was envisaged as a towering symbol of modernity. It would have dwarfed the Eiffel Tower in Paris. The tower's main form was a twin helix which spiraled up to 400 m in height,[3] around which visitors would be transported with the aid of various mechanical devices. The main framework would contain four large suspended geometric structures. These structures would rotate at different rates. At the base of the structure was a cube which was designed as a venue for lectures, conferences and legislative meetings, and this would complete a rotation in the span of one year. Above the cube would be a smaller pyramid housing executive activities and completing a rotation once a month. Further up would be a cylinder, which was to house an information centre, issuing news bulletins and manifestos via telegraph, radio and loudspeaker, and would complete a rotation once a day. At the top, there would be a hemisphere for radio equipment. There were also plans to install a gigantic open-air screen on the cylinder, and a further projector which would be able to cast messages across the clouds on any overcast day.[4]

Evaluations

Even if the gigantic amount of required steel had been available in bankrupt post-revolutionary Russia, in the context of housing shortages and political turmoil, there are serious doubts about its structural practicality.[4]

Symbolically, the tower was said to represent the aspirations of its originating country[3] and a challenge to the Eiffel Tower as the foremost symbol of modernity.[5] Soviet critic Viktor Shklovsky is said to have called it a monument "made of steel, glass and revolution."[3]

Models

Model of Tatlin's Tower in the courtyard of the Royal Academy, London.

There are models of Tatlin's Tower at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden, at Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, and at Musée National d'Art Moderne at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. A 1:42 model was built at The Royal Academy of Arts, London in November 2011. In September 2017, the same 1:42 model was erected as part of the 'Russian Season' at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich. It is expected to become a permanent feature of the University of East Anglia's 'sculpture park' once the exhibition closes in February 2018.[6]

Ai Weiwei's 2007 sculpture Fountain of Light, currently on display at the Louvre Abu Dhabi, is modelled on the Tatlin Tower.[7][8]

See also

- Shukhov Tower

Tower Bawher, an abstract short film inspired by Tatlin's Tower.

References and sources

- References

^ Honour, H. and Fleming, J. (2009) A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, p. 819. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 9781856695848

^ Janson, H.W. (1995) History of Art. 5th edn. Revised and expanded by Anthony F. Janson. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 820.

ISBN 0500237018

^ abc Ching, Francis D.K., et al. (2011). Global History of Architecture. 2nd edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., p. 716.

^ ab Grey, Camilla (1986). The Russian Experiment in Art. London: Thames & Hudson.

^ Hughes, L. (2010). "Art—Russia" in W. H. McNeill, J. H. Bentley, D. Christian, R. C. Croizier, J. R. McNeill, H. Roupp, & J. P. Zinsser (Eds.), Berkshire Encyclopedia of World History (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 259–267). Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire Publishing, p. 266.

^ "Sainsbury Centre adds 10-metre tower to UEA sculpture park - Press Release - UEA". www.uea.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-09-26.

^ "Fountain of Light by Ai Weiwei". My Favorite Arts.

^ Wainwright, Oliver (7 November 2017). "Louvre Abu Dhabi: Jean Nouvel's spectacular palace of culture shimmers in the desert". the Guardian.

- Sources

Tatlin's Tower: Monument to Revolution, Norbert Lynton, Yale University Press, 2008

Art and Literature under the Bolsheviks: Volume One – The Crisis of Renewal Brandon Taylor, Pluto Press, London 1991

Tatlin, edited by L.A. Zhadova, Thames and Hudson, London 1988

Concepts of Modern Art, edited by Nikos Stangos, Thames and Hudson, London 1981

Vladimir Tatlin and the Russian avant-garde, John Milner, Yale University Press, New Haven 1983

Nikolai Punin. The Monument to the Third International, 1920

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tatlin's Tower. |

Tatlin's Tower and the World — Artist group's web site on the project of building Tatlin's Tower in full scale.

Architecture and the Russian Avant-garde (Pt 2 Tatlins Tower) on YouTube – using computer graphics, archive footage and locations in Moscow, this film illustrates Tatlin's contribution to world architecture and how his tower may have looked in Moscow had it been built after the revolution; by Michael Craig; 3:37.