British Expeditionary Force (World War II)

| British Expeditionary Force (World War II) | |

|---|---|

Bren carriers of the 13/18th Royal Hussars during an exercise near Vimy, 11 October 1939 | |

| Active | 2 September 1939 – 31 May 1940 |

| Disbanded | 1940 |

| Country | Britain |

| Branch | Army |

| Type | Expeditionary Force |

| Role | Field operations in France and the Low Countries |

| Size | 13 divisions (maximum) |

| Part of | 1er groupe d'armées (1st Army Group) Front du Nord-est (North-Eastern Front) |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | John Vereker, 6th Viscount Gort (Lord Gort) |

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was the name of the British Army in Western Europe during the Second World War from 2 September 1939 when the BEF GHQ was formed until 31 May 1940, when GHQ closed down. Military forces in Britain were under Home Forces command. During the 1930s, the British government planned to deter war by rearming from the very low level of readiness of the early 30s and abolished the Ten Year Rule. The bulk of the extra money went to the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force but plans were made to re-equip a small number of Army and Territorial Army divisions for service overseas.

General Lord Gort was appointed to the command of the BEF on 3 September 1939 and the BEF began moving to France on 4 September 1939. The BEF assembled along the Belgian–French border. The BEF took their post to the left of the French First Army under the command of the French 1st Army Group (1er groupe d'armées) of the North-Eastern Front (Front du Nord-est). Most of the BEF spent the 3 September 1939 to 9 May 1940 digging field defences on the border. When the Battle of France (Fall Gelb) began on 10 May 1940, the BEF constituted 10 percent of the Allied forces on the Western Front.

The BEF participated in the Dyle Plan, a rapid advance into Belgium to the line of the river Dyle but the 1st Army Group had to retreat rapidly through Belgium and north-western France, after the German breakthrough further south at the Battle of Sedan (12–15 May). A local counter-attack at the Battle of Arras (1940) (21 May) was a considerable tactical success but the BEF, French and Belgian forces north of the Somme retreated to Dunkirk on the French North Sea coast soon after, British and French troops being evacuated in Operation Dynamo (26 May – 4 June) after the capitulation of the Belgian army.

Saar Force, the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division and reinforcements, had taken over part of the Maginot Line for training. The force fought with local French units after 10 May, then joined the Tenth Army south of the Somme, along with the improvised Beauman Division and the 1st Armoured Division, to fight in the Battle of Abbeville (27 May – 4 June). The British tried to re-build the BEF with Home Forces divisions training in Britain, troops evacuated from France and lines-or-communications troops south of the Somme river (informally known as the 2nd BEF) but BEF GHQ was not reopened.

After the success of the second German offensive in France (Fall Rot), the 2nd BEF and Allied troops were evacuated from Le Havre in Operation Cycle (10–13 June) and the French Atlantic and Mediterranean ports in Operation Ariel (15–25 June, unofficially to 14 August). The Navy rescued 558,032 people, including 368,491 British troops but the BEF lost 66,426 men of whom 11,014 were killed or died of wounds, 14,074 wounded and 41,338 men missing or captured. About 700 tanks, 20,000 motor bikes, 45,000 cars and lorries, 880 field guns and 310 larger equipments, about 500 anti-aircraft guns, 850 anti-tank guns, 6,400 anti-tank rifles and 11,000 machine-guns were abandoned. As units arrived in Britain they returned to the command of Home Forces.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 1918–1932

1.2 Rearmament

1.2.1 Limited Liability

1.2.2 Continental commitment

2 Prelude

2.1 Despatch of the BEF

2.2 Phoney War

2.3 Dyle plan, Breda variant

3 Battle

3.1 10–21 May 1940

3.1.1 Ardennes

3.1.2 BEF retreat

3.1.3 Loss of the construction divisions

3.2 21–23 May

3.3 Retreat to Dunkirk

3.3.1 Le Paradis rearguard

3.3.2 II Corps rearguard

3.4 Dunkirk

4 After Dunkirk

4.1 Lines-of-communication

4.2 Second BEF

4.3 St. Valery

4.4 Le Havre

4.5 Retreat from Normandy

4.6 Operation Ariel

5 Aftermath

5.1 Analysis

5.2 Casualties

6 Map gallery

6.1 Commemoration

7 Notes

8 Footnotes

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Background

1918–1932

After 1918, the prospect of war seemed so remote, that Government expenditure on the armed forces was determined by the assumption that no great war was likely. Spending varied from year to year and between the services but from July 1928 to March 1932, the formula of the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) was

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

...that it should be assumed for the purpose of framing the estimates of the fighting services that at any given date there will be no major war for ten years.

— CID[1]

and spending on equipment for the army varied from £1,500,000 to £2,600,000 per year from 1924 to 1933, averaging £2,000,000 or about 9 percent of armaments spending a year. Until the early 1930s, the War Office intended to maintain a small, mobile and professional army and a start was made on motorising the cavalry and the artillery. By 1930, the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) had been mechanised, some of the artillery could be moved by tractors, and a few engineer, signals and cavalry units had received lorries. From 1930–1934, the Territorial Army (TA) artillery, engineer, signals units were equipped with lorries and in 1938 the regular army gained its establishment of wheeled vehicles and half of its tracked vehicles, except for tanks. From 1923 to 1932, 5,000 motor vehicles were ordered at a rate of about 500 a year, just under half being six-wheeler lorries. By 1936, the army had 379 tanks, of which 209 were light tanks and 166 were mediums; 304 were considered obsolete; 69 of the light tanks were modern but did not begin to reach the army until 1935.[2] The rule had reduced war spending from £766 million in 1920 to £102 million when it was abolished on 23 March 1932. The British army had fewer men than in 1914, no organisation or equipment for a war in Europe, and it would have taken the War Office three weeks to mobilise only an infantry division and a cavalry brigade.[3]

Rearmament

Limited Liability

In March 1932, the Ten-Year Rule was abolished and in 1934, the Cabinet resolved to remedy equipment deficiencies in the armed forces over the next five years. The army was always the least favoured force but equipment spending increased from £6,900,000 from 1933–1934 financial year (1 April to 31 March), to £8,500,000 the following year and to more than £67,500,000 by 1938–1939 but the share of spending on army equipment only grew beyond 25 percent of all military equipment spending in 1938. The relative neglect of the army led to a theory of limited liability until 1937, in which Britain would not send a great army to Europe in time of war. In 1934, the Defence Requirements Sub-Committee (DRC) of the CID assumed that a regular field army of five divisions was to be equipped as an expeditionary force, eventually to be supplemented by parts of the Territorial Army. The force and its air support would act as a deterrent greatly disproportionate to its size; plans were made to acquire sufficient equipment and training for the TA to provide a minimum of two extra divisions on the outbreak of war. It was expected that a British army in Europe would receive continuous reinforcement and in 1936, a TA commitment of twelve divisions was envisaged by Alfred Duff Cooper, the Secretary of State for War.[4]

As rearmament of the navy and the air force continued, the nature of an army fit to participate in a European war was kept under review and in 1936, the Cabinet ordered the Chiefs of Staff Sub-Committee of the CID to provide a report on the role of an expeditionary force and the relative values of the army and the air force as deterrents for the same cost. The chiefs were in favour of a balanced rearmament but within financial limits, the air force should be favoured. In 1937, the Minister argued that a continental commitment was no longer feasible and that France did not now expect a big land army along with the navy and air force, Germany had guaranteed Belgian neutrality and that if the quantity of money was limited, defence against air attack, trade protection and the defence of overseas territories were more important and had to be secured before Britain could support allies in the defence of their territories. The continental hypothesis came fourth and the main role of the army was to protect the empire, which included the anti-aircraft defence of the United Kingdom (with the assistance of the TA). In 1938, limited liability reached its apogee, just as rearmament was maturing and the army was considering the new conspectus, a much more ambitious rearmament plan.[5]

In February 1938, the CID ruled that planning should be based on limited liability; between late 1937 and early 1939, equipment for the five-division field army was reduced to that necessary for colonial warfare in the Far East. In Europe, the field force could only conduct defensive warfare and would need a big increase in ammunition and the refurbishment of its tank forces. The field force continued to be the least-favoured part of the least-favoured military arm and in February 1938, the Secretary of State warned that possible allies should be left in no doubt about the effectiveness of the army. The re-armament plans for the field force remained deficiency plans, rather than plans for expansion. The July 1934 deficiency plan was costed at £10,000,000 but cut by 50 percent by the cabinet; by the first rearmament plan of 1936, the cost of the deficiency plan for the next five years had increased £177,000,000. In the first version of the new conspectus, spending was put at £347,000,000, although in 1938 this was cut to £276,000,000, still substantially more than the deficiency plan for 1936 but much of this sum was for anti-aircraft defence, a new duty imposed on the army.[5]

Continental commitment

| Items | 1938 | 1939 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tanks Carriers | 5,025 | 7,096 tanks | |

| Carriers | above | 11,647 | |

| vehicles Field/AA guns | 25,545 | 376,299 | |

| 2-pdr guns | nil | 13,561 | |

| Shells (non-AA) | 14.8m | 64.4m | |

Obtaining equipment for the Field Force benefited from plans for the TA which, sometimes covertly, was used as a device to get more equipment which could be used by the regular army. At first it was admitted in the deficiency programmes of 1935–1936, in which an expansion of the TA in three stages to twelve divisions, was to complement the five regular divisions. The Cabinet postponed this plan for three years, during which the policy of limited liability precluded such developments, except for the purchase of the same training equipment for the TA as that used by the army, equivalent to that needed to equip two regular divisions, which was the maximum commitment promised to the French in 1938.[7][8] The mobile division was split into two divisions and some extra equipment went to artillery and engineer units.[7] By 1938 the deficiency programme was due to mature; in the wake of the Munich Crisis in September and the loss of the 35 divisions of the Czechoslovak Army, the Cabinet approved a plan for a ten-division army equipped for continental operations and a similar-sized TA, in early 1939.[9] By reacting to events, the British Cabinet made it inevitable that,

...the size of the Army was bound to be adjusted to what the French thought was the least they needed and the British the most that they could do.

— Postan[9]

and the British made a commitment on 21 April 1939 to provide an army of six regular and 26 Territorial divisions, introduced equipment scales for war, and began conscription to provide the manpower.[10] In February 1939, the first four regular army divisions of the Field Force had been promised to the French, to reach the assembly area in France on the thirtieth day after mobilisation. Until this commitment, no staff work had been done and there was no information about French ports and railways and no modern maps.[11]

Prelude

Despatch of the BEF

After the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, the Cabinet appointed General John Vereker, 6th Viscount Gort (Lord Gort) to the command of the BEF on 3 September, subordinate to General Alphonse Georges, the French commander of the North-eastern Theatre of Operations, with the right of appeal to the British government.[12] The BEF was to assemble on the Franco-Belgian border and advanced parties of troops left Portsmouth on 4 September under Plan W4 and the first troop convoy left the ports on the Bristol Channel and Southampton on 9 September, disembarking at Cherbourg on 10 September and Nantes and St Nazaire two days later. German submarines had been held back by Hitler to avoid provoking the Allies and only a few mines were laid near Dover and Weymouth. By 27 September, 152,000 soldiers, 21,424 vehicles, 36,000 long tons (36,578 t) tons of ammunition, 25,000 long tons (25,401 t) of petrol and 60,000 long tons (60,963 t) of frozen meat had been landed in France.[13]

On 3 October, I Corps with the 1st Infantry Division and 2nd Infantry Division began to take over the front line allocated to the BEF and II Corps with the 3rd Infantry Division and 4th Infantry Division followed on 12 October; the 5th Infantry Division arrived in December.[14] By 19 October, the BEF had received 25,000 vehicles to complete the first wave. The majority of the troops were stationed along the Franco-Belgian border but British divisions took turns to serve with the French Third Army on the Maginot Line. In April 1940, the 51st Highland Infantry Division, reinforced by additional units and called Saar Force took over part of the French line.[15]Belgium and the Netherlands were neutral and free of Allied or German military forces and for troops along the Maginot Line, inactivity and an undue reliance on the fortifications, which were believed to be impenetrable, led to "Tommy Rot" (portrayed in the song "Imagine Me on the Maginot Line"). Morale was high amongst the British troops but the limited extent of German actions by 9 May 1940, led many to assume that there would not be much chance of a big German attack in that area.[16]

From January to April 1940, eight Territorial divisions arrived in France but the 12th (Eastern) Division, 23rd (Northumbrian) Division and 46th (North Midland and West Riding) Infantry Division, informally called labour divisions, were not trained or equipped to fight.[17] The labour divisions consisted of 26 new infantry battalions which had spent their first months guarding vulnerable points in England but had received very little training. Battalions and some engineers were formed into nominal brigades but lacked artillery, signals or transport. The divisions were used for labour from St Nazaire in Normandy to St Pol in French Flanders, on the understanding that they would not be called upon to fight before they had completed their training.[18]

By May 1940 the BEF order of battle consisted of ten infantry divisions ready for field service, in I Corps, II Corps, III Corps and Saar Force. BEF GHQ commanded the Field Force and the BEF Air Component Royal Air Force (RAF) of about 500 aircraft but the Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) long-range bomber force was under the control of RAF Bomber Command. GHQ consisted of men from Headquarters (HQ) Troops (consisting of the 1st Battalion, Welsh Guards, the 9th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment and the 14th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers), the 1st Army Tank Brigade, 1st Light Armoured Reconnaissance Brigade, HQ Royal Artillery and the 5th Infantry Division.[19]

Phoney War

General Lord Gort, commander of the BEF, with General Alphonse Georges, commander of the French Ninth Army.

The period from September 1939 to 10 May 1940 was known as the "Phoney War", which consisted of little more than minor clashes by reconnaissance patrols. The section of the Franco-Belgian border to be held by the BEF at that time stretched from Armentières westward towards Menin, then south to the junction of the border and the River Escaut (the French name for the Scheldt) at Maulde, forming a salient around Lille and Roubaix. The British began to dig trenches, weapons pits and pill boxes and this known as the "Gort Line".[20] The first BEF fatality was 27-year-old Corporal Thomas William Priday, from the 1st Battalion, King's Shropshire Light Infantry, attached to the 3rd Infantry Brigade of the 1st Infantry Division, killed on 9 December 1939, when his patrol set off a booby-trap and was fired upon by friendly troops.[21] By November 1939, the French had decided that a defence along the Dyle Line in Belgium was feasible but the British were lukewarm about an advance into Belgium. Gamelin talked them round and on 9 November, the Dyle Plan/Plan D was adopted and on 17 November, Gamelin issued a directive that day detailing a line from Givet to Namur, the Gembloux Gap, Wavre, Louvain and Antwerp. For the next four months, the Dutch and Belgian armies laboured over their defences, the BEF expanded and the French army received more equipment and training.[22]

Dyle plan, Breda variant

By May 1940, the 1st Army Group defended the Channel coast to the west end of the Maginot Line. The Seventh Army (Général d'armée Henri Giraud), BEF (General Lord Gort), First Army (Général d'armée Georges Maurice Jean Blanchard) and Ninth Army (Général d'armée André Corap) were ready to advance to the Dyle Line, by pivoting on the right (southern) Second Army.[a] The Seventh Army would take over west of Antwerp, ready to move into Holland and the Belgians were expected to delay a German advance and then retire from the Albert Canal to the Dyle, between Antwerp to Louvain. The BEF was to defend about 12 mi (20 km) of the Dyle from Louvain to Wavre and the First Army on the right of the BEF was to hold 22 mi (35 km) from Wavre across the Gembloux Gap to Namur. The gap from the Dyle to Namur north of the Sambre, with Maastricht and Mons on either side, had few natural obstacles and led straight to Paris. The Ninth Army would take post south of Namur, along the Meuse to the left (northern) flank of the Second Army.[24]

The Second and Ninth armies were dug in on the west bank of the Meuse on ground that was easily defended and behind the Ardennes, giving plenty of warning of a German attack. After the transfer of the Seventh Army, seven divisions remained behind the Second and Ninth armies and other divisions could be moved from behind the Maginot Line. All but one division were either side of the junction of the two armies, GQG being more concerned about a German attack past the north end of the Maginot Line and then south-east through the Stenay Gap, for which the divisions behind the Second Army were well placed.[25] On 8 November, Gamelin added the Seventh Army, containing some of the best and most mobile French divisions, to the left flank of the 1st Army Group to move into Holland and protect the Scheldt estuary. In March, Gamelin ordered that the Seventh Army would advance to Breda to link with the Dutch. The Seventh Army, on the left flank of the Dyle manoeuvre, would be linked to it and if the Seventh Army crossed into the Netherlands, the left flank of the 1st Army Group was to advance to Tilburg if possible and certainly to Breda. The Seventh Army was to take post between the Belgian and Dutch armies turning east, a distance of 109 mi (175 km), against German armies only 56 mi (90 km) distant from Breda.[26]

Battle

10–21 May 1940

At 4:35 a.m., the German invasion of France and the Low Countries commenced. The French Seventh Army drove forward on the northern flank and advanced elements reached Breda on 11 May. The French collided with the 9th Panzer Division and the advance of the 25e Division d'Infanterie Motorisée was stopped by German infantry, tanks and Ju 87 (Stuka) dive-bombers, as the 1ère Division Légère Mécanisée was forced to retreat. (French heavy tanks were still on trains south of Antwerp.) The Seventh Army retired from the Bergen op Zoom–Turnhout Canal Line 20 mi (32 km) from Antwerp, to Lierre 10 mi (16 km) away on 12 May; on 14 May the Dutch surrendered.[27][28]

In Belgium, German glider troops captured fort Eben-Emael by noon on 11 May; the disaster forced the Belgians to retreat to a line from Antwerp to Louvain on 12 May, far too soon for the French First Army to arrive and dig in.[28] The Corps de Cavalerie fought the XVI Panzer Corps in the Battle of Hannut (12–14 May) the first ever tank-against-tank battle and the Corps de Cavalerie then withdrew behind the First Army, which had arrived at the Dyle Line. On 15 May, the Germans attacked the First Army along the Dyle, causing the meeting engagement that Gamelin had tried to avoid. The First Army repulsed the XVI Panzer Corps but during the Battle of Gembloux (14–15 May) GQG realised that the main German attack had come further south, through the Ardennes. The French success in Belgium contributed to the disaster on the Meuse at Sedan and on 16 May, Blanchard was ordered to retreat to the French border.[29]

The codename Operation David initiated the British part of the Dyle Plan. The British vanguard, spearheaded by the armoured cars of the 12th Royal Lancers, crossed the border at 1:00 p.m. on 10 May, cheered on by crowds of Belgian civilians who lined their route.[30] The section of the Dyle allocated to the BEF ran about 22 mi (35 km) from Louvain, south-west to Wavre. Gort had decided to man the front line with only three divisions, the 3rd Division from II Corps in the north, the 1st and 2nd Divisions from I Corps further south, leaving some battalions to defend a frontage double that recommended by British Army field manuals.[31] The remaining BEF divisions were positioned to provide defence in depth all the way back to the River Escaut. The riverbank to the north of Louvain was already occupied by Belgian troops, who refused to give way to the British, even when Brooke appealed to the King of the Belgians and had to be ordered out by Georges. The British infantry battalions posted along the bank of the Dyle began to arrive on 11 May and started to dig in, protected by a screen of light tanks and Bren carriers operating on the western side of the river, to keep German reconnaissance patrols away; they were withdrawn on 14 May when all the front line units were in place and the bridges were blown behind them.[32]

The first organised German attacks commenced on the BEF's front on 15 May, the reconnaissance troops of three German infantry divisions having been dispersed on the previous evening. Attacks on Louvain by the German 19th Division were repulsed by the 3rd Division.[33] Further south, the river was only about 15 ft (4.6 m) wide, enough to prevented tanks from crossing but less of an obstacle to infantry. During one attack at the south of the BEF line, Richard Annand of the Durham Light Infantry earned a Victoria Cross. German bridgeheads across the Dyle were either eliminated or contained by British counter-attacks.[34]

Ardennes

From 10–11 May, the XIX Panzer Corps engaged the two cavalry divisions of the Second Army, surprising them with a far larger force than expected and forced them back. The Ninth Army to the north had also sent its two cavalry divisions forward, which were withdrawn on 12 May, before they met German troops. The first German unit reached the Meuse in the afternoon but the local French commanders thought that they were far ahead of the main body and would wait before trying to cross the Meuse. From 10 May, Allied bombers had been sent to raid northern Belgium, to delay the German advance while the First Army moved up but attacks on the bridges at Maastricht had been costly failures, the 135 RAF day bombers being reduced to 72 operational aircraft by 12 May. At 7:00 a.m. on 13 May, the Luftwaffe began bombing the French defences around Sedan and continued for eight hours with about 1,000 aircraft in the biggest air attack in history.[35]

Little material damage was done to the Second Army but morale collapsed. In the French 55e Division at Sedan, some troops began to straggle to the rear and in the evening panic spread through the division. German troops attacked across the river at 3:00 p.m. and had gained three footholds on the west bank by nightfall.[36] The French and the RAF managed to fly 152 bomber and 250 fighter sorties on the Sedan bridges on 14 May but only in formations of 10–20 aircraft. The RAF lost 30 of 71 aircraft and the French were reduced to sending obsolete bombers to attack in the afternoon, also with many losses. On 16 May, the 1st Army Group was ordered to retreat from the Dyle Line, to avoid being trapped by the German breakthrough against the Second and Ninth armies but on 20 May, the Germans reached Abbeville on the Channel coast, cutting off the northern armies.[37]

BEF retreat

The plan for the BEF withdrawal was that under cover of darkness, units would thin-out their front and make a phased and orderly withdrawal before the Germans realised what was happening. The objective for the night of 16/17 May was the Charleroi to Willebroek Canal (the Line of the Senne), the following night to the River Dendre from Maubeuge to Termonde and the Escaut to Antwerp (the Dendre Line), and finally on 18/19 May, to the Escaut from Oudenarde to Maulde on the French border (the Escaut Line). The order to withdraw was greeted with astonishment and frustration by the British troops who felt that they had held their own, but they were unaware of the deteriorating situation elsewhere.[38] The withdrawal went mainly according to plan but required hard fighting from the corps rearguards. A communication breakdown caused a loss of coordination with the Belgian Army to the north-west of II Corps and a dangerous gap opened up between the two; fortunately it was covered by British light armour before the Germans could discover and exploit it.[39]

Loss of the construction divisions

The three Territorial divisions which had arrived in April, equipped only with small arms and intended for construction and labouring tasks, were distributed across the path of the German spearhead on its drive to the sea. On 16 May, Georges realised that the Panzer divisions might reach the coast and outflank all the Allied armies to the north of them. He asked for the 23rd Division to defend the Canal du Nord at Arleux. The British staff were of the opinion that the German breakthrough consisted of small detachments of light reconnaissance troops and that using these lightly armed and largely untrained troops against them did not seem unreasonable. That area was otherwise devoid of Allied units, so there was little alternative. The three divisions were grouped together in an improvised corps called Petreforce and on 18 and 19 May, the Territorials, lacking motor transport, began to march or entrain towards their defence positions.[18]

The 70th Brigade of the 23rd Division dug in on the Canal Line but was ordered to withdraw towards Saulty on 20 May; in the process they were caught in the open by elements of 6th and 8th Panzer Divisions, from which only a few hundred survivors escaped. The 69th Brigade defended Arras and the 12th Division fought to delay 2nd Panzer Division on the Canal Line near Arras, at Doullens, Albert and Abbeville. The 138th Brigade of the 46th Division fought on the Canal Line but the 137th Brigade trains were attacked by the Luftwaffe en route; the survivors were able to withdraw to Dieppe and later fought on the Seine Crossings. The 139th Brigade fought on the River Scarpe and later defended the Dunkirk perimeter. By the end of 20 May, the divisions had ceased to exist, in most cases having only delayed the German advance by a few hours.[40]

21–23 May

The push by Army Group A towards the coast, combined with the approach of Army Group B from the north-east, left the BEF surrounded on three sides and by 21 May, the BEF had been cut off from its supply depots south of the Somme. The British counter-attacked at the Battle of Arras on the same day. This was well to the south of the main BEF force on the Escaut, where seven BEF divisions were placed in the front line. The British divisions were facing nine German infantry divisions, who began their attack on the morning of 21 May with a devastating artillery barrage. Shortly afterwards, infantry assaults started along the whole front, crossing the canalised river either by inflatable boats or by clambering across the wreckage of demolished bridges.[41] Although the Escaut line was penetrated in numerous places, all the German bridgeheads were either thrown back or contained by vigorous but costly British counter-attacks and the remaining German troops were ordered to retire across the river by the night of 22 May. Later that same night, events further south prompted an order for the BEF to retire again, this time back to the Gort Line on the Franco-Belgian border.[42] The Channel ports were at risk of capture. Fresh troops were rushed from England to defend Boulogne and Calais but after hard fighting, both ports were captured by 26 May in the Battle of Boulogne and Siege of Calais. Gort ordered the BEF to withdraw to Dunkirk, the only port from which the BEF could still escape.[43]

Retreat to Dunkirk

Le Paradis rearguard

Detached rifle companies of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment and the 1st Battalion, Royal Scots of the 2nd Infantry Division provided rearguards during the evacuation of troops from Dunkirk.[44] The 2nd Royal Norfolks held the line at La Bassée Canal and with the 1/8th Lancashire Fusiliers, the 2nd Royal Norfolks and 1st Royal Scots held the villages of Riez du Vinage and Le Cornet Malo and protect the battalion headquarters at Le Paradis, for as long as possible. During the fighting, units had become separated but the Royal Norfolks held on until 5:15 p.m. when the Norfolks ran out of ammunition.[45][46] The 99 survivors tried to break out but eventually surrendered to the 2nd Infantry Regiment (SS-Hauptsturmführer and Obersturmbannführer Fritz Knöchlein) of the SS Division Totenkopf. The 99 prisoners were marched to farm buildings nearby, fired on by two machine guns; bayonets to finish off survivors. Albert Pooley and William O'Callaghan, hid in a pigsty and were rescued later, before being taken prisoner by a Wehrmacht unit, spending the rest of the war in prison camps.[47]

II Corps rearguard

The II Corps commander Lieutenant General Alan Brooke, was ordered to conduct a holding action with the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 50th Infantry Divisions along the Ypres–Comines canal as far as Yser, while the rest of the BEF fell back. At mid-day on 27 May, the Germans attacked south of Ypres with three divisions. German infantry infiltrated through the defenders and forced them back.[48] On 27 May, Brooke ordered Major-General Bernard Montgomery to extend the 3rd Division line to the left, freeing the 10th and 11th Brigades of the 4th Division to join the 5th Division at Messines Ridge. The 10th and 11th Brigades managed to clear the ridge of Germans and by 28 May, the brigades were dug in east of Wytschaete. Brooke ordered a counter-attack led by the 3rd Battalion, Grenadier Guards and the 2nd Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment of the 1st Division. The North Staffords advanced as far as the Kortekeer River, while the Grenadiers managed to reach the Ypres–Comines Canal but could not hold it. The counter-attack disrupted the Germans, holding them back a little longer while the BEF continued its retreat.[49]

Dunkirk

The Germans failed to capture Dunkirk and on 31 May, General Georg von Küchler assumed command of the German forces on the Dunkirk perimeter and planned a bigger attack for 11:00 a.m. on 1 June. The French held the Germans back while the last troops were evacuated and just before midnight on 2 June, Admiral Bertram Ramsay, the officer commanding the evacuation, received the signal "BEF evacuated"; the French began to fall back slowly. By 3 June, the Germans were 2 mi (3.2 km) from Dunkirk and at 10:20 a.m. on 4 June, the Germans hoisted the swastika over the docks.[50] Before Operation Dynamo, 27,936 men were embarked from Dunkirk; most of the remaining 198,315 men, a total of 224,320 British troops along with 139,097 French and some Belgian troops, were evacuated from Dunkirk between 26 May and 4 June, though having to abandon much of their equipment, vehicles and heavy weapons.[51]

After Dunkirk

Lines-of-communication

Allied forces north of the Somme were cut off by the German advance on the night of 22/23 May, which isolated the BEF from its supply entrepôts of Cherbourg, Brittany and Nantes. Dieppe was the main BEF medical base and Le Havre the principal supply and ordnance source. The main BEF ammunition depot and its infantry, machine-gun and base depots were around Rouen, Évreux and Épinay. Three Territorial divisions and three lines-of-communication battalions had been moved north of the Seine on 17 May.[52] Rail movements between these bases and the Somme was impeded by German bombing and trains arriving from the north full of Belgian and French troops; the roads also filled with retreating troops and refugees. Acting Brigadier Archibald Beauman lost contact with BEF GHQ.[53]

Beauman improvised Beauforce from two infantry battalions, four machine-gun platoons and a company of Royal Engineers. Vicforce (Colonel C. E. Vickary) took over five provisional battalions from troops in base depots, who had few arms and little equipment.[53] The Germans captured Amiens on 20 May, setting off panic and the spread of alarmist reports. Beauman ordered the digging of a defence line along the Andelle and Béthune to protect Dieppe and Rouen.[53] From 1–3 June, the 51st Highland Division (formerly Saar Force) a Composite Regiment and the remnants of the 1st Support Group, 1st Armoured Division, relieved the French opposite the Abbeville–St. Valery bridgehead. The Beauman Division held a 55 mi (89 km) line from Pont St. Pierre, 11 mi (18 km) south-east of Rouen to Dieppe on the coast, which left the British units holding 18 mi (29 km) of the front line, 44 mi (71 km) of the Bresle and 55 mi (89 km) of the Andelle–Béthune line, with the rest of IX Corps on the right flank.[54]

Second BEF

On 31 May, GHQ BEF closed and 2 June, Brooke visited the War Office and was given command of a new II Corps, comprising the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division and the 1st Armoured Division, with the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Infantry Division from Home Forces in Britain, then the 3rd Infantry Division as soon as it was ready.[55][56]. Brooke warned that the enterprise was futile, except as a political gesture. On 6 June, the Cabinet decided to reconstitute the BEF (Second BEF is an informal post-war term) with Gort remaining as commander in chief.[57] A brigade group (the 157th Infantry) of the 52nd (Lowland) Division departed for France on 7 June and Brooke returned five days later.[58]

On 9 June, the French port Admiral at Le Havre reported that Rouen had fallen and that the Germans were heading for the coast. Ihler, the IX Corps commander and Fortune decided that their only hope of escape was via Le Havre. The port admiral requested British ships for 85,000 troops but this contradicted earlier plans for the IX Corps retirement and Dill hesitated, ignorant that the original plan was untenable. Karslake urged that the retirement be accelerated but had no authority to issue orders. Only after contacting the Howard-Vyse Military Mission at GQG and receiving a message that the 51st (Highland) Division was retreating with IX Corps towards Le Havre, did Dill learn the truth.[59]

St. Valery

The retreat to the coast began after dark and the last troops slipped away from the Béthune river at 11:00 p.m. Units were ordered to dump non-essential equipment and each gun were reduced to 100 rounds to make room on the RASC transport for the men. The night move was difficult as French troops, many horse-drawn, encroached on the British route and alarmist rumours spread. Fortune and Ihler set up at a road junction near Veules-les-Roses to direct troops to their positions and by the morning of 11 June, IX Corps had established a defence round St. Valery. French transport continued to arrive at the perimeter and it was difficult in some places to recognise German troops following up, which inhibited defensive fire.[60] That night, Fortune signalled that it was now or never. Troops not needed to hold the perimeter moved down to the beaches and the harbour. An armada of 67 merchant ships and 140 small craft had been assembled but few had wireless; thick fog ruined visual signalling and prevented the ships from moving inshore. Only at Veules-les-Roses at the east end of the perimeter, were many soldiers rescued, under fire from German artillery, which damaged the destroyers HMS Bulldog, Boadicea and Ambuscade. Near dawn, the troops at the harbour were ordered back into the town and at 7:30 a.m., Fortune signalled that it might still be possible to escape the next night, then discovered that the local French commander had already surrendered.[61]

Le Havre

Fortune had detached Arkforce comprising the 154th Infantry Brigade, A Brigade of the Beauman Division, two artillery regiments and engineers to guard Le Havre. Arkforce moved on the night of 9/10 June towards Fécamp, where most had passed through before the 7th Panzer Division arrived. A Brigade managed to force its way out but lost the wireless truck for liaison with the 51st (Highland) Division and Stanley-Clarke ordered Arkforce on to Le Havre.[59] On 9 June, the Admiralty ordered Le Havre to be evacuated and the Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth sent a flotilla leader, HMS Codrington across the channel, accompanied by six British and two Canadian destroyers, smaller craft and Dutch coasters (known as schuyts). On 10 June, HMS Vega escorted three blockships to Dieppe and two were sunk in the approach channel.[62] Beach parties landed at Le Havre on 10 June and the evacuation began on 11 June, hindered somewhat by Luftwaffe bombing. The troopship SS Bruges was beached and the electric power was cut, rendering the cranes on the docks useless and improvised methods to embark heavy equipment were too slow. On 12 June, RAF fighters deterred more raids and the quartermaster of the 14th Royal Fusiliers got the transport away over the Seine via the ferry at Caudebec and ships at Quillebeuf at the river mouth.[63] The Navy got 2,222 British troops from Le Havre to England and 8,837 were taken to Cherbourg to join the forces being assembled for the new II Corps (Second BEF).[64]

Retreat from Normandy

By 13 June, the Germans were across the Seine and the Tenth Army was isolated on the Channel coast. The AASF was ordered to retreat towards Nantes or Bordeaux, while supporting the French armies and flew armed reconnaissance sorties over the Seine from dawn, which cost ten aircraft and crews; bad weather limited fighter sorties to the coast.[65] On 14 June, attacks resumed against German units south of the Seine but the weather deteriorated and fewer sorties were flown. Seven Blenheims were shot down raiding Merville airfield but ten Fighter Command squadrons patrolled twice in squadron strength or provided bomber escorts, the biggest effort since Dunkirk, as fighters of the AASF patrolled south of the Seine. The remnants of the 1st Armoured Division and two brigades of the Beauman Division had got south of the river, with thousands of lines-of-communication troops but only the 157th Infantry Brigade, 52nd (Lowland) Division was in contact with the Germans, occupying successive defensive positions. The French armies were forced into divergent retreats, with no obvious front line. On 12 June, Weygand had recommended that the French government seek an armistice, which led to an abortive plan to create a defensive zone in Brittany.[66]

On 14 June, Brooke was able to prevent the rest of the 52nd (Lowland) Division being sent to join the 157th Infantry Brigade Group and during the night Brooke was told that he was no longer under French command and must prepare to withdraw the British forces from France. Marshall-Cornwall was ordered to take command of all British forces under the Tenth Army as Norman Force and while continuing to co-operate, to withdraw towards Cherbourg. The rest of the 52nd (Lowland) Division was ordered back to a line near Cherbourg to cover the evacuation on 15 June. The AASF was directed to send the last bomber squadrons back to Britain and use the fighters to cover the evacuations. The German advance began again during the day, with the 157th Infantry Brigade Group engaged east of Conches-en-Ouche with the Tenth Army, which was ordered back to a line from Verneuil to Argentan and the Dives river, where the British took over an 8 mi (13 km) front. German forces followed up quickly and on 16 June, Altmayer ordered the army to retreat into the Brittany peninsula.[67]

Operation Ariel

From 15–25 June, British and Allied ships were covered by five RAF fighter squadrons in France, assisted by aircraft from England as they embarked British, Polish and Czech troops, civilians and equipment from the French Atlantic ports, particularly St. Nazaire and Nantes. The Luftwaffe attacked the evacuation ships and on 17 June, sank the troopship RMS Lancastria in the Loire estuary. About 2,477 passengers and crew were saved but thousands of troops, RAF personnel and civilians were on board and at least 3,500 people died.[68] Some equipment was embarked but ignorance about the progress of the German Army and alarmist reports, led some operations to be terminated early and much equipment needlessly was destroyed or left behind. About 700 tanks, 20,000 motor bikes, 45,000 cars and lorries, 880 field guns and 310 larger equipments, about 500 anti-aircraft guns, 850 anti-tank guns, 6,400 anti-tank rifles and 11,000 machine-guns were abandoned.[69]

The official evacuation ended on 25 June, according to the terms of the Armistice of 22 June 1940 but informal departures continued from French Mediterranean ports until 14 August. From Operation Cycle at Le Havre, elsewhere along the Channel coast, to the termination of Operation Ariel, another 191,870 BEF troops were rescued, bringing the total of military and civilian personnel returned to Britain during the Battle of France to 558,032, including 368,491 British troops.[68] Left behind in France was eight to ten divisions' worth of equipment and ammunition.[69] As troops returned to Britain, they increased the manpower of the Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces (General Edmond Ironside 27 May to 20 July, then Brooke) but the trained and equipped units had been stripped from Home Forces and sent to France; only about two divisions' worth of equipment remained in the country. The equivalent of twelve divisions returned to Britain but these could only be re-equipped by the Ministry of Supply from production. Deliveries of 25-pounder field guns had increased to about 35 per month by June but the establishment of one infantry division was 72 guns.[70]

Aftermath

Analysis

In 1953, Lionel Ellis, the British official historian, wrote that by the end of the informal evacuations on 14 August, another 191,870 men had been evacuated after the 366,162 rescued by Operation Dynamo, a total of 558,032 people, 368,491 being British troops.[71] In 2001, Brodhurst wrote that many civilians escaped from French Atlantic and Mediterranean ports to England via Gibraltar and that 22,656 more civilians left the Channel Islands, from 19–23 June.[72] Much military equipment was lost but 322 guns, 4,739 vehicles, 533 motor cycles. 32,303 long tons (32,821 t) of ammunition, 33,060 long tons (33,591 t) of stores, 1,071 long tons (1,088 t) of petrol, 13 light tanks and 9 cruiser tanks were recovered. During the BEF evacuations 2,472 guns, anti-aircraft guns and anti-tank guns were destroyed or abandoned along with 63,879 vehicles consisting of 20,548 motor cycles and 45,000 cars and lorries, 76,697 long tons (77,928 t) of ammunition, 415,940 long tons (422,615 t) of supplies and equipment and 164,929 long tons (167,576 t) of petrol.[73]

For every seven soldiers who escaped through Dunkirk, one man was left behind as a prisoner of war. The majority of these prisoners were sent on forced marches into Germany to towns such as Trier, the march taking as long as twenty days. Others were moved on foot to the river Scheldt and were sent by barge to the Ruhr. The prisoners were then sent by rail to POW camps in Germany. The majority (those below the rank of corporal) then worked in German industry and agriculture for five years.[74] An intelligence report by the German IV Army Corps, which had been engaged against the BEF from the Dyle line to the coast, was circulated to the divisions training for Operation Sealion said of the men of the BEF

The English soldier was in excellent physical condition. He bore his own wounds with stoical calm. The losses of his own troops he discussed with complete equanimity. He did not complain of hardships. In battle he was tough and dogged. His conviction that England would conquer in the end was unshakeable.... The English soldier has always shown himself to be a fighter of high value. Certainly the Territorial divisions are inferior to the Regular troops in training but where morale is concerned they are their equal.... In defence the Englishman took any punishment that came his way.

— German intelligence report[75]

Casualties

The BEF lost 66,426 men, 11,014 killed and died of wounds, 14,074 wounded and 41,338 men missing or taken prisoner.[76]

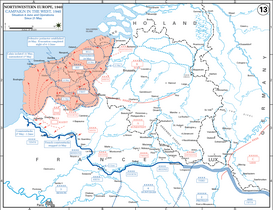

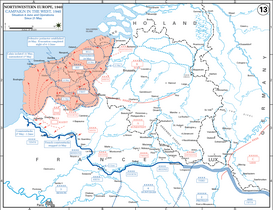

Map gallery

- German advances through The Netherlands, Belgium and France

Maginot line defences

10 to 16 May 1940

16 to 21 May

21 May to 6 June

4–12 June

13–25 June

Commemoration

No campaign medal was awarded for the Battle of France but serviceman who had spent 180 days in France between 3 September 1939 and 9 May 1940, or "a single day, or part thereof" in France or Belgium between 10 May and 19 June 1940, qualified for the 1939–1945 Star.[77]

Notes

^ It is a French convention to list military forces from left to right.[23]

Footnotes

^ Postan 1952, p. 1.

^ Postan 1952, pp. 1–2, 6–7.

^ Collier 2004, p. 21.

^ Postan 1952, pp. 9, 27–29.

^ ab Postan 1952, pp. 29–30.

^ Postan 1952, p. 73.

^ ab Postan 1952, pp. 33–34.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 5.

^ ab Postan 1952, p. 72.

^ Postan 1952, pp. 72–73.

^ Bond 2001, pp. 1–2.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 11.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 15.

^ Bond 2001, p. 6.

^ Ellis 2004, pp. 20, 249–252.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 33.

^ Bond 2001, p. 8.

^ ab Tackle 2009, p. 23.

^ Ellis 2004, pp. 19, 357–368.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, pp. 509–511, 7, 172.

^ Charman 2010, p. 284.

^ Doughty 2014a, pp. 7–8.

^ Edmonds 1928, p. 267.

^ Doughty 2014a, p. 11.

^ Doughty 2014a, p. 12.

^ Doughty 2014a, pp. 8–9.

^ Rowe 1959, pp. 142–143, 148.

^ ab Jackson 2003, pp. 37–38.

^ Jackson 2003, pp. 38–39.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, pp. 59–61.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, pp. 512–513, 78.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, pp. 75–76.

^ Thompson 2009, pp. 37–38.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, pp. 77–79.

^ Jackson 2003, pp. 39–43.

^ Jackson 2003, pp. 43–46.

^ Jackson 2003, pp. 48–52, 56.

^ Thompson 2009, p. 47.

^ Thompson 2009, pp. 63–65.

^ Tackle 2009, pp. 26–37.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, pp. 521, 156–157.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, pp. 171–172.

^ Ellis 2004, pp. 153–170, 149.

^ Jackson 2003, pp. 94–97.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, pp. 285–292.

^ Jackson 2003, pp. 285–289.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, pp. 297–301.

^ Thompson 2009, pp. 174–179.

^ Thompson 2009, pp. 182–184.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, pp. 455–457.

^ Ellis 2004, pp. 183–248.

^ Ellis 2004, pp. 252–253.

^ abc Ellis 2004, pp. 253–254.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 265.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 238.

^ Tackle 2009, pp. 104–105.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 276.

^ Alanbrooke 2002, pp. 74–75.

^ ab Karslake 1979, pp. 180–181.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 288.

^ Roskill 1957, pp. 230–232.

^ Roskill 1957, pp. 231, 230.

^ Karslake 1979, pp. 181–182.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 293.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 295.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 296.

^ Ellis 2004, pp. 300–302.

^ ab Roskill 1957, pp. 229–240.

^ ab Postan 1952, p. 117.

^ Collier 2004, pp. 143, 127.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 305.

^ Brodhurst 2001, p. 137.

^ Ellis 2004, p. 327.

^ Longden 2008, pp. 383–404.

^ Ellis 2004, pp. 326, 394.

^ Sebag-Montefiore 2007, p. 506.

^ The 1939-1945 Star Regulations Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Alanbrooke, Field Marshal Lord (2002) [2001]. Danchev, Alex; Todman, Daniel, eds. War Diaries (Phoenix Press, London ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-1-84212-526-7..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Bond, B. (2001). "Introduction: Preparing the Field Force, February1939 – May 1940". In Bond, B.; Taylor, M. D. The Battle for France & Flanders Sixty Years On. Barnsley: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-811-4.

Brodhurst, R. (2001). "The Royal Navy's Role in the Campaign". In Bond, B.; Taylor, M. D. The Battle for France & Flanders Sixty Years On. Barnsley: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-811-4.

Charman, Terry (2010). The Day We went to War. London: Random House. ISBN 978-0-7535-3668-1.

Collier, B. (2004) [1957]. Butler, J. R. M., ed. The Defence of the United Kingdom. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-845-74055-9. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

Doughty, R. A. (2014) [1985]. The Seeds of Disaster: The Development of French Army Doctrine, 1919–39 (Stackpole, Mechanicsburg, PA ed.). Hamden, CT: Archon Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1460-0.

Edmonds, J. E. (1928). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915: Battles of Aubers Ridge, Festubert andLoos. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II. London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962526.

Ellis, Major L. F. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1953]. Butler, J. R. M., ed. The War in France and Flanders 1939–1940. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-056-6. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

Hinsley, F. H.; et al. (1979). British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. I. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630933-4.

Horne, A. (1982) [1969]. To Lose a Battle: France 1940 (Penguin repr. ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-14-005042-4.

Jackson, J. T. (2003). The Fall of France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280300-9.

Karslake, B. (1979). 1940 The Last Act: The Story of the British Forces in France after Dunkirk. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-240-2.

Longden, Sean (2008). Dunkirk: The Men They Left Behind. London: Constable. ISBN 978-1-84529-520-2.

Postan, M. M. (1952). British War Production. History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Civil Series. London: HMSO. OCLC 459583161.

Roskill, S. W. (1957) [1954]. Butler, J. R. M., ed. The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Defensive. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. I (4th impr. ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 881709135. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

Rowe, V. (1959). The Great Wall of France: The Triumph of the Maginot Line (1st ed.). London: Putnam. OCLC 773604722.

Sebag-Montefiore, H. (2007). Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-102437-0.

Tackle, Patrick (2009). The British Army in France After Dunkirk. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-852-2.

Thompson, Julian (2009). Dunkirk: Retreat to Victory. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-43796-7.

Further reading

Books

Atkin, Ronald (1990). Pillar of Fire: Dunkirk 1940. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-078-4.

Gibbs, N. H. (1976). Grand Strategy. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. I. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630181-9.

May, Ernest R. (2000). Strange Victory: Hitler's Conquest of France. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-329-3.

Postan, M. M.; et al. (1964). Hancock, K., ed. Design and Development of Weapons: Studies in Government and Industrial Organisation. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Civil Series. London: HMSO. OCLC 681432.

Richards, Denis (1974) [1953]. Royal Air Force 1939–1945: The Fight At Odds. I (pbk. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-771592-9. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

Warner, P. (2002) [1990]. The Battle of France, 1940: 10 May – 22 June (Cassell Military Paperbacks repr. ed.). London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-304-35644-7.

Reports

War Department (31 March 1942). The German Campaign in Poland September 1 to October 5, 1939 (Report). Digests and Lessons of Recent Military Operations. U. S. War Department, General Staff. OCLC 16723453. AG 062.11 (1–26–42). Retrieved 23 June 2018.

Theses

Harris, J. P. (1983). The War Office and Rearmament 1935–39 (PhD thesis). Registration. King's College London (University of London). OCLC 59260791. Docket uk.bl.ethos.289189. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

Nelsen II, J. T. (1987). Strength Against Weakness: The Campaign In Western Europe, May–June 1940 (Monograph). School of Advanced Military Studies US Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 21094641. Docket ADA 184718. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

Perry, F. W. (1982). Manpower and Organisational Problems in the Expansion of the British and other Commonwealth Armies during the Two World Wars (PhD thesis). London University. OCLC 557366960. Docket uk.bl.ethos.286414. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

Salmon, R. E. (2013). The Management of Change: Mechanizing the British Regular and Household Cavalry Regiments 1918–1942 (PhD thesis). University of Wolverhampton. OCLC 879390776. Docket uk.bl.ethos.596061. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

Stedman, A. D. (2007). 'Then what could Chamberlain do, other than what Chamberlain did'? A Synthesis and Analysis of the Alternatives to Chamberlain's Policy of Appeasing Germany, 1936–1939 (PhD thesis). Kingston University. OCLC 500402799. Docket uk.bl.ethos.440347. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to British Expeditionary Force 1939-1940. |

- British Military History: France and Norway 1940

- London Gazette Dispatches