Wittelsbach-class battleship

Lithograph of Zähringen in 1902 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators: | |

| Preceded by: | Kaiser Friedrich III class |

| Succeeded by: | Braunschweig class |

| Built: | 1899–1904 |

In commission: | 1902–1921 |

| Planned: | 5 |

| Completed: | 5 |

| Lost: | 1 |

| Scrapped: | 4 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 12,798 t (12,596 long tons) |

| Length: | 126.8 m (416 ft 0 in) |

| Beam: | 22.8 m (74 ft 10 in) |

| Draft: | 7.95 m (26 ft 1 in) |

| Installed power: | 14,000 PS (13,808 ihp; 10,297 kW) |

| Propulsion: | 3 shafts, triple expansion steam engines |

| Speed: | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range: | 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi); 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

The Wittelsbach-class battleships were a group of five pre-dreadnought battleships of the Imperial German Navy. They were the first battleships produced under the Navy Law of 1898. The class was composed of the lead ship, Wettin, Zähringen, Schwaben, and Mecklenburg. All five ships were laid down between 1899 and 1900, and finished by 1904. The ships of the Wittelsbach class were similar in appearance to their predecessors of the Kaiser Friedrich III class, however, they had a flush main deck, as opposed to the lower quarterdeck of the Kaiser Friedrich class, and had a more extensive armor belt. Their armament was almost identical, though more efficiently arranged.

The ships were commissioned into the German fleet between 1902 and 1904, where they joined the I Squadron of the battle fleet. They were rapidly made obsolete by the launch of HMS Dreadnought in 1906. By the outbreak of World War I in 1914, they were no longer fit for front-line service, though they saw some limited duty in the Baltic Sea against the Russian Navy. In 1916 the five ships were disarmed and employed in secondary roles. Wittelsbach, Wettin, and Schwaben became training ships, Mecklenburg was used as a prison ship and later as a floating barracks, and Zähringen became a target ship. All of the ships save Zähringen were broken up in 1921–22. Zähringen was rebuilt as a radio-controlled target ship in the mid-1920s. During World War II, she was badly damaged in a bombing raid in 1944 and scuttled in the final days of the war. She was eventually broken up in situ in 1949–50.

Contents

1 Design

1.1 General characteristics and machinery

1.2 Armament and armor

2 Ships

3 Service history

4 Footnotes

4.1 Notes

4.2 Citations

5 References

Design

The ships of the Wittelsbach class were the first battleships built under the first Naval Law of 1898,[1] and they were designed by Prof. Dr. Dietrich, then the chief constructor. The ships represented an incremental improvement over the preceding Kaiser Friedrich III class. Although Konteradmiral (Rear Admiral) Emil Felix von Bendemann had argued for an increase in the main battery from the 24-centimeter (9.4 in) guns of the Kaiser Friedrich III class to more powerful 28 cm (11 in) guns, the Wittelsbach-class ships were equipped with the same armament of 24 cm guns, but were given an additional torpedo tube.[2][3] They also had improved defensive capabilities, as they were protected by a more extensive armored belt. Additionally, they received more powerful engines and were slightly faster.[1][2] They also differed from the preceding ships in their main deck, the entire length of which was flush; in the Kaiser Friedrich III-class ships, the quarterdeck was cut down.[4]

General characteristics and machinery

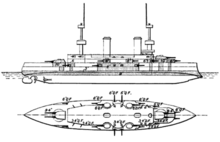

Line-drawing of the Wittelsbach class

The ships of the Wittlesbach class were 125.2 meters (410 ft 9 in) long at the waterline and 126.8 m (416 ft 0 in) overall. They had a beam of 22.8 m (74 ft 10 in) and a draft of 7.95 m (26 ft 1 in) forward. The Wittelsbachs were designed to displace 11,774 metric tons (11,588 long tons) with a standard load, and displaced up to 12,798 metric tons (12,596 long tons) at full combat weight. The Wittelsbach-class ships' hulls were built with transverse and longitudinal steel frames. Steel hull plates were riveted to the structure created by the frames. The hull was split into 14 watertight compartments and included a double bottom that ran for 70 percent of the length of the ship.[5]

The ships were regarded in the German Navy as excellent sea boats with an easy roll; the ships rolled up to 30° with a period of 10 seconds. They maneuvered easily; at hard rudder the ships lost up to 60 percent speed and heeled over 9°. However, they suffered from severe vibration, particularly at the stern, at high speeds. They also had very wet bows, even in moderate seas. The ships had a crew of 33 officers and 650 enlisted men. However, when serving as a squadron flagship, the crew was augmented by an additional 13 officers and 66 enlisted men. While acting as a second command ship, 9 officers and 44 enlisted men were added to the standard crew. Wittelsbach and her sisters carried a number of smaller vessels, including two picket boats, two launches, one pinnace, two cutters, two yawls, and two dinghies.[6]

The five ships of the Wittelsbach class each had three three-cylinder triple expansion steam engines. The outer engines drove a three-bladed screw that was 4.8 m (15 ft 9 in) in diameter; the central shaft drove a four-bladed screw that was slightly smaller, at 4.5 m (14 ft 9 in) in diameter. To produce steam to power the engines, each ship had six marine-type boilers, with the exception of Wettin and Mecklenburg, which had six Thornycroft boilers, along with six transverse cylindrical boilers. Steering was controlled by a single large rudder. Electrical power was supplied by four generators that each produced 230 kilowatts (310 hp) at 74 volts, although in Wittelsbach the generators were rated at 248 kilowatts (333 hp).[6]

The propulsion system was rated at 14,000 metric horsepower (13,808 ihp; 10,297 kW), which produced a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). On trials, however, the five ships had significantly varied performances. Schwaben, the slowest ship, reached 13,253 PS (13,072 ihp; 9,748 kW) for a top speed of only 16.9 knots (31.3 km/h; 19.4 mph). Wettin, the fastest, managed 15,530 PS (15,318 ihp; 11,422 kW) and a top speed of 18.1 knots (33.5 km/h; 20.8 mph). They carried 650 metric tons (640 long tons) in their holds, but fuel capacity could be nearly tripled to 1,800 metric tons (1,772 long tons) with the usage of additional spaces in the ships. This provided a maximum range of 5,000 nautical miles (9,260 km; 5,754 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[5]

Armament and armor

Lithograph of Mecklenburg in 1902

The ships' armament was nearly identical to the preceding Kaiser Friedrich III class. The primary armament consisted of a battery of four 24 cm (9.4 in) SK L/40 guns in twin gun turrets,[a] one fore and one aft of the central superstructure.[8] The guns were mounted in Drh.L. C/98 turrets, which allowed elevation to 30° and depression to −5°. At maximum elevation, the guns could hit targets out to 16,900 meters (18,500 yd). The guns fired 140-kilogram (310 lb) shells at a muzzle velocity of 835 meters per second (2,740 ft/s). Each gun was supplied with 85 shells, for a total of 340. The turrets were hydraulically operated[9][10] Secondary armament included eighteen 15 cm (5.9 inch) SK L/40 guns; four were emplaced in single turrets amidships and the rest were mounted in MPL casemates.[b] These guns fired armor-piercing shells at a rate of 4–5 per minute. The ships carried 120 shells per gun, for a total of 2,160 rounds total. The guns could depress to −7 degrees and elevate to 20 degrees, for a maximum range of 13,700 m (14,990 yd). The shells weighed 51-kilogram (112 lb) and were fired at a muzzle velocity of 735 meters per second (2,410 ft/s). The guns were manually elevated and trained.[11][10]

The ships also carried twelve 8.8 cm (3.45 in) SK L/30 quick-firing guns,[6] also mounted in casemates and pivot mounts. These guns were supplied with between 170 and 250 shells per gun. These guns fired 7.04 kg (15.5 lb) at a muzzle velocity of 590 mps (1,936 fps). Their rate of fire was approximately 15 shells per minute; the guns could engage targets out to 6,890 m (7,530 yd). The gun mounts were manually operated.[10][12] The ships' gun armament was rounded out by twelve machine cannons.[6] The ships were also armed with six 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, all submerged in the hull; one was in the bow, another in the stern, and two on each broadside.[6] These weapons were 5.1 m (201 in) long and carried an 87.5 kg (193 lb) TNT warhead. They could be set at two speeds for different ranges. At 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph), the torpedoes had a range of 800 m (870 yd). At an increased speed of 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph), the range was reduced to 500 m (550 yb).[13]

The five Wittelsbach class battleships were armored with Krupp steel. Their armored decks were 50 millimeters (2.0 in) thick, with sloped sides that ranged in thickness from 75 to 120 mm (3.0 to 4.7 in). The sloped section of the deck connected it to the main armored belt, which was 225 mm (8.9 in) in the central citadel, where the ship's vitals were. This included ammunition magazines and the propulsion system. The belt was reduced to 100 mm (3.9 in) on either end of the central citadel; the bow and stern were not protected with any armor. The entire length of belt was backed by 100 mm of teak planking.[5] Directly above the main belt, the 15 cm casemate guns were protected with 140 mm (5.5 in) thick steel plating. The 15 cm guns in turrets were more exposed and therefore slightly better protected: their side armor was increased to 150 mm (5.9 in), with 70 mm (2.8 in) thick gun shields. The 24 cm gun turrets had the heaviest armor aboard ship: 250 mm (9.8 in) thick sides and 50 mm thick roofs. The forward conning tower also had 250 mm thick sides, though its roof was only 30 mm (1.2 in) thick. The rear conning tower was much less protected. Its sides were only 140 mm thick; the roof was 30 mm thick.[5]

Ships

| Ship | Builder[6] | Laid down | Launched[6] | Completed[6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Wittelsbach | Kaiserliche Werft Wilhelmshaven | 30 September 1899[2] | 3 July 1900 | 15 October 1902 |

Wettin | Schichau-Werke, Danzig | 10 October 1899[14] | 6 June 1901 | 1 October 1902 |

Zähringen | Germaniawerft, Kiel | 21 November 1899[15] | 12 June 1901 | 25 October 1902 |

Schwaben | Kaiserliche Werft Wilhelmshaven | 15 September 1900[16] | 19 August 1901 | 13 April 1904 |

Mecklenburg | AG Vulcan, Stettin | 15 May 1900[17] | 9 November 1901 | 25 May 1903 |

Service history

SMS Wittlesbach

In the early 1900s, the German fleet was organized as the Home Fleet (German: Heimatflotte).[4] After joining the fleet, the Wittelsbach-class ships were assigned to the I Battle Squadron, where they replaced the older Brandenburg-class battleships. By 1907, the Braunschweig and Deutschland classes had come into service. With two full battle squadrons, the fleet was reorganized as the High Seas Fleet.[18]

Like the Kaiser Friedrich III-class ships, the Wittelsbachs were withdrawn from active service after the advent of the dreadnoughts. The five ships were recalled to active service at the outbreak of war in 1914.[4] They were assigned to the IV Battle Squadron and deployed to the Baltic. The ships were based in Kiel and placed under the command of Vice Admiral Ehrhard Schmidt.[19] In early September 1914, the ships conducted a result-less sweep into the Baltic against the Russian navy operating there.[20] In May 1915, four of the Wittelsbachs sailed into the Baltic and bombarded Libau, which was subsequently captured by the German army.[21] The five ships of the class were moved to Libau during the Battle of the Gulf of Riga in August 1915, though they did not see any combat during the operation.[22]

British submarines were becoming increasingly active in the Baltic by late 1915; several cruisers had been sunk and the elderly Wittelsbach-class ships could no longer be risked there.[23] Therefore, due to their age and vulnerability, they were withdrawn from active service and disarmed by 1916. They were used as training ships, with the exception of Mecklenburg, which was used as a prison ship. In 1919, Wittelsbach and Schwaben were converted into depot ships for minesweepers. The entire class, with the exception of Zähringen, were struck from the navy list after the end of World War I. Mecklenburg was struck on 27 January 1920, Wettin followed on 11 March 1920, and Wittelsbach and Schwaben were struck on 8 March 1921. The four ships were broken up between 1921–22.[6]Zähringen was converted into a radio-controlled target ship in 1926–27. Royal Air Force bombers sank the ship in Gotenhafen in 1944; the wreck was broken up in 1949–50.[4]

Footnotes

Notes

^ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick firing, while the L/40 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/40 gun is 40 caliber, meaning that the gun is 40 times as long as it is in diameter.[7]

^ MPL stands for Mittel-Pivot-Lafette (Central pivot mounting).[7]

Citations

^ ab Gardiner, Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 248.

^ abc Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 8, p. 90.

^ Herwig, p. 43.

^ abcd Gardiner & Gray, p. 141.

^ abcd Gröner, p. 16.

^ abcdefghi Gröner, p. 17.

^ ab Grießmer, p. 177.

^ Hore, p. 67.

^ Friedman, p. 141.

^ abc Gardiner & Gray, p. 140.

^ Friedman, p. 143.

^ Friedman, p. 146.

^ Friedman, p. 336.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 8, p. 80.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 8, p. 126.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 7, p. 140.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 6, p. 59.

^ Herwig, p. 45.

^ Halpern, p. 192.

^ Halpern, p. 185.

^ Halpern, pp. 192–193.

^ Halpern, p. 197.

^ Herwig, p. 168.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wittelsbach class battleship. |

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

Gröner, Erich (1990). Jung, Dieter; Maass, Martin, eds. German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Volume 6) [The German Warships] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ASIN B003VHSRKE.

Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Volume 7) [The German Warships] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ASIN B003VHSRKE.

Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Volume 8) [The German Warships] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ASIN B003VHSRKE.

Hore, Peter (2006). The Ironclads. London: Southwater Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.