Kiel Canal

| Nord-Ostsee-Kanal | |

|---|---|

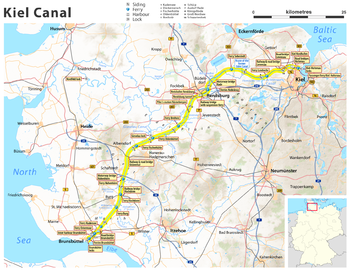

Current map of Kiel Canal in Schleswig-Holstein | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 98.26 km (61.06 miles) |

| Maximum boat length | 235 metres (771 ft) |

| Maximum boat beam | 32.5 metres (107 ft) |

| Minimum boat draft | 9.5 metres (31 ft) |

| Minimum boat air draft | 40 metres (130 ft) |

| History | |

| Construction began | 1887 |

| Date completed | 1895 (1895) |

| Date extended | 1907–14 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Brunsbüttel (North Sea) |

| End point | Kiel (Baltic Sea) |

Locks at Brunsbüttel connecting the canal to the River Elbe estuary, and thence to the North Sea

The Kiel Canal (German: Nord-Ostsee-Kanal, literally "North-[to]-Baltic Sea canal", formerly known as the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Kanal) is a 95-kilometre (59 mi) long freshwater canal in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The canal was finished in 1895, but later widened, and links the North Sea at Brunsbüttel to the Baltic Sea at Kiel-Holtenau. An average of 250 nautical miles (460 km) is saved by using the Kiel Canal instead of going around the Jutland Peninsula. This not only saves time but also avoids storm-prone seas and having to pass through the Sound or Belts.

Besides its two sea entrances, the Kiel Canal is linked, at Oldenbüttel, to the navigable River Eider by the short Gieselau Canal.[1]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Construction and expansion

1.2 After World War I

2 Operation

3 Crossings

4 See also

5 References

6 External links

History

The first connection between the North and Baltic Seas was constructed while the area was ruled by Denmark-Norway. It was called the Eider Canal, which used stretches of the Eider River for the link between the two seas. Completed during the reign of Christian VII of Denmark in 1784, the Eiderkanal was a 43-kilometre (27 mi) part of a 175-kilometre (109 mi) waterway from Kiel to the Eider River's mouth at Tönning on the west coast. It was only 29 metres (95 ft) wide with a depth of 3 metres (10 ft), which limited the vessels that could use the canal to 300 tonnes.[2]

After 1864 Second Schleswig War put Schleswig-Holstein under the government of Prussia (from 1871 the German Empire), a new canal was sought by merchants and by the German navy, which wanted to link its bases in the Baltic and the North Sea without the need to sail around Denmark.[2]

Construction and expansion

In June 1887, construction started at Holtenau (de), near Kiel. The canal took over 9,000 workers eight years to build. On 20 June 1895 the canal was officially opened by Kaiser Wilhelm II for transiting from Brunsbüttel to Holtenau. The next day, a ceremony was held in Holtenau, where Wilhelm II named it the Kaiser Wilhelm Kanal (after his grandfather, Kaiser Wilhelm I), and laid the final stone.[3] The opening of the canal was filmed by British director Birt Acres; surviving footage of this early film is preserved in the Science Museum in London.[4] The first Trans-Atlantic sailing ship to pass through the canal was Lilly, commanded by Johan Pitka. Lilly. a barque, was a wooden sailing ship of about 390 tons built 1866 in Sunderland, U.K. She had a length of 127.5 feet (38.9 m), beam 28.7 feet (8.7 m), depth of 17.6 feet (5.4 m) and a 32-foot (9.8 m) keel.[5]

In order to meet the increasing traffic and the demands of the Imperial German Navy, between 1907 and 1914 the canal width was increased. The widening of the canal allowed the passage of a Dreadnought-sized battleship. This meant that these battleships could travel from the Baltic Sea to the North Sea without having to go around Denmark. The enlargement projects were completed by the installation of two larger canal locks in Brunsbüttel and Holtenau.[6]

After World War I

After World War I, the Treaty of Versailles required the canal to be open to vessels of commerce and of war of any nation at peace with Germany, while leaving it under German administration.[7] (The United States opposed this proposal to avoid setting a precedent for similar concessions on the Panama Canal.[8]) The government under Adolf Hitler repudiated its international status in 1936, but the canal was reopened to all traffic after World War II.[9] In 1948, the current name was adopted.

The canal was partially closed in March 2013 after two lock gates failed at the western end near Brunsbüttel. Ships larger than 125 metres (410 ft) were forced to navigate via Skagerrak, a 450-kilometre (280 mi) detour. The failure was blamed on neglect and a lack of funding by the German Federal Government which has been in financial dispute with the state of Schleswig-Holstein regarding the canal. Germany's Transport Ministry promised rapid repairs.[10]

Operation

There are detailed traffic rules for the canal. Each vessel in passage is classified in one of six traffic groups according to its dimensions. Larger ships are obliged to accept pilots and specialised canal helmsmen, in some cases even the assistance of a tugboat. Furthermore, there are regulations regarding the passing of oncoming ships. Larger ships may also be required to moor at the bollards provided at intervals along the canal to allow the passage of oncoming vessels. Special rules apply to pleasure craft.[citation needed]

View west-southwest from the aft lounge of the cruise ship Norwegian Dream

While most large, modern cruise ships cannot pass through this canal due to clearance limits under bridges, the SuperStar Gemini has special funnels and masts that can be lowered for passage. Swan Hellenic's Minerva, P&O Cruises's Adonia, Fred. Olsen Cruise Lines' ships MV Balmoral (1987), and MV Boudicca 'Cruise & Maritime Voyages' ships MS Marco Polo and MV Astoria, 'Oceania Cruises' Regatta, and Nautica, and MS Prinsendam of Holland America Line are able to transit the canal. Several of the Viking cruise ships are made specifically with Kiel Canal passage in mind, namely the Sea and Sky models.[citation needed]

All permanent, fixed bridges crossing the canal since its construction have a clearance of 42 metres (138 ft).

Maximum length for ships passing the Kiel Canal is 235.50 metres (772.6 ft); with the maximum width (beam) of 32.50 metres (106.6 ft) these ships can have a draught of up to 7.00 metres (22.97 ft). Ships up to a length of 160.00 metres (524.93 ft) may have a draught up to 9.50 metres (31.2 ft).[11] The bulker Ever Leader (deadweight 74001 t) is considered to be the cargo ship that to date has come closest to the overall limits.[12]

Crossings

The Rendsburg High Bridge

The Levensau High Bridge

Several railway lines and federal roads (Autobahnen and Bundesstraßen) cross the canal on eleven fixed links. The bridges have a clearance of 42 metres (138 ft) allowing for ship heights up to 40 metres (130 ft). The oldest bridge still in use is the Levensau High Bridge from 1893; however, the bridge will have to be replaced in the course of a canal expansion already underway. In sequence and in the direction of the official kilometre count from west (Brunsbüttel) to east (Holtenau) these crossings are:

Brunsbüttel High Bridge, four lane crossing of Bundesstraße 5

Hochdonn High Bridge of the Marsh Railway

Hohenhörn High Bridge for Autobahn 23

Grünental High Bridge for railway line Neumünster-Heide and Bundesstraße 204

Rendsburg High Bridge for the Neumünster–Flensburg railway, suspended from which is a transporter bridge for local traffic

Rendsburg pedestrian tunnel [13]

Kanaltunnel Rendsburg, road tunnel for Bundesstraße 77 (four lanes)

Rade High Bridge for Autobahn A7

Levensau High Bridge from 1893 for the Kiel–Flensburg railway and a local road

New Levensau High Bridge for Bundesstraße 76 (four lanes)

Holtenau High Bridges, two parallel bridges with three car lanes each as well as pavements for pedestrians and cyclists

Local traffic is also catered for by 14 ferry lines. Most noteworthy is the “hanging ferry” (German: Schwebefähre) beneath the Rendsburg High Bridge. All ferries are run by the Canal Authority and their use is free of charge.

See also

- List of canals in Germany

- Canal del Dique

- Panama Canal

- Suez Canal

- Corinth Canal

References

^ Sheffield, Barry (1995). Inland Waterways of Germany. St Ives: Imray Laurie Norie & Wilson. ISBN 0-85288-283-1..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Gollasch, Stephan; Galil, Bella S.; Cohen, Andrew N. (24 Sep 2006). Bridging Divides: Maritime Canals as Invasion Corridors. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1-4020-5047-3.

^ "Kiel-Canal History". UCA United Canal Agency GmbH. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

^ "Opening of the Kiel Canal". Screenonline. Retrieved 2007-03-30.

^ Pitka, J., Minu Mälestused II, Laevandus, pp 149-156, Tallinn, Ilutrükk, Tartu, 1938.

^ http://www.kiel-canal.de/kiel-canal/history/

^ Treaty of Versailles, Article 380. Treaty of Versailles/Part XII. Wikisource.

Treaty of Versailles/Part XII. Wikisource.

^ Platzöder, Renate; Verlaan, Philomène, eds. (1996). The Baltic Sea: New Developments in National Policies and International Cooperation. The Hague: Nijhoff. ISBN 9789041103574.

^ http://www.kiel-canal.de/kiel-canal/history/

^ "Locked Out: Disrepair Forces Closure of Vital Shipping Lane". Der Spiegel. 8 March 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

^

§ 42

Seeschifffahrtsstraßen-Ordnung [ German Traffic Regulations for Navigable Maritime Waterways] of 22 October 1998, BGBl. Part I, p. 3209

^ "Nord-Ostsee-Kanal nimmt wieder Fahrt auf - Verkehrszahlen im 3.Quartal 2009" [Kiel Canal – traffic figures 3rd quarter 2009] (PDF). www.wsv.de (in German). Wasser- und Schifffahrtsdirektion Nord. 21 October 2009.Early October the largest cargo ship by the combination of length, beam and draught ever transited the Kiel Canal, the Ever Leader (225 m/32.26 m/7.30 m). IMO: 9182186.

^ "Fußgängertunnel Nord-Ostsee Kanal in Rendsburg". Wasserstraßen- und Schifffahrtsamt Kiel-Holtenau.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kiel Canal. |

- Official site

- Time-lapse movie "Kiel-Canal Transit In 9 Minutes" released by UNITED CANAL AGENCY

- Movie about a container ship transiting the canal

Coordinates: 53°53′N 9°08′E / 53.883°N 9.133°E / 53.883; 9.133