SMS Wettin

SMS Wettin in 1907 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Wettin |

| Namesake: | House of Wettin |

| Builder: | Schichau, Danzig |

| Laid down: | 10 October 1899 |

| Launched: | 6 June 1901 |

| Commissioned: | 1 October 1902 |

| Fate: | Scrapped in 1921 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Wittelsbach-class pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 12,798 t (12,596 long tons) |

| Length: | 126.8 m (416 ft 0 in) |

| Beam: | 22.8 m (74 ft 10 in) |

| Draft: | 7.95 m (26 ft 1 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 3 shafts, triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed: | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range: | 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi); 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

SMS Wettin ("His Majesty's Ship Wettin")[a] was a pre-dreadnought battleship of the Wittelsbach class of the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy). She was built by Schichau Seebeckwerft in Danzig. Wettin was laid down in October 1899, and was completed October 1902. She and her sister ships—Wittelsbach, Zähringen, Schwaben and Mecklenburg—were the first capital ships built under the Navy Law of 1898. Wettin was armed with a main battery of four 24 cm (9.4 in) guns and had a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph).

Wettin saw service in I Squadron of the German fleet for most of her career, along with her sister ships. She was occupied with extensive annual training, as well as making good-will visits to foreign countries. The training exercises provided the framework for the High Seas Fleet's operations during World War I. The ship was decommissioned in June 1911 as dreadnought battleships began to enter service but was reactivated for duty as a gunnery training ship between December 1911 and mid-1914.

After the start of World War I in August 1914, the Wittelsbach-class ships were mobilized and designated IV Battle Squadron. She saw limited duty in the Baltic Sea, but the ship played a minor role in the Battle of the Gulf of Riga in August 1915, though Wettin saw no combat with Russian forces. By late 1915, crew shortages and the threat from British submarines forced the Kaiserliche Marine to withdraw older battleships like Wettin from active service. For the remainder of the war, Wettin served as a training ship for naval cadets and as a depot ship. The ship was stricken from the navy list after the war and sold for scrapping in 1921. Her bell is on display at the Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr in Dresden.

Contents

1 Description

2 Service history

2.1 Construction – 1905

2.2 1906–1914

2.3 World War I

2.3.1 Battle of the Gulf of Riga

2.3.2 Subsequent activity

3 Footnotes

3.1 Notes

3.2 Citations

4 References

Description

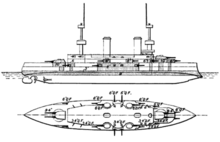

Line-drawing of the Wittelsbach class

After the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) ordered the four Brandenburg-class battleships in 1889, a combination of budgetary constraints, opposition in the Reichstag (Imperial Diet), and a lack of a coherent fleet plan delayed the acquisition of further battleships. The Secretary of the Reichsmarineamt (Imperial Navy Office), Vizeadmiral (VAdm—Vice Admiral) Friedrich von Hollmann struggled throughout the early and mid-1890s to secure parliamentary approval for the first three Kaiser Friedrich III-class battleships. In June 1897, Hollmann was replaced by Konteradmiral (KAdm—Rear Admiral) Alfred von Tirpitz, who quickly proposed and secured approval for the first Naval Law in early 1898. The law authorized the last two ships of the class, as well as the five ships of the Wittelsbach class,[1] the first class of battleship built under Tirpitz's tenure. The Wittelsbachs were broadly similar to the Kaiser Friedrichs, carrying the same armament but with a more comprehensive armor layout.[2][3]

Wettin was 126.8 m (416 ft 0 in) long overall, with a beam of 22.8 m (74 ft 10 in), and a draft of 7.95 m (26 ft 1 in) forward and 8.04 m (26 ft 5 in) aft. She displaced 12,798 t (12,596 long tons) at full load. The ship was powered by three 3-cylinder vertical triple expansion engines that drove three screws. Steam was provided by six Thornycroft boilers and six cylindrical boilers, all of which burned coal. Wettin's powerplant was rated at 14,000 metric horsepower (13,808 ihp; 10,297 kW), which generated a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). The ship could steam for 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). She had a crew of 30 officers and 650 enlisted men.[4]

Wettin's armament consisted of a main battery of four 24 cm (9.4 in) SK L/40 guns in twin gun turrets,[b] one fore and one aft of the central superstructure.[6] Her secondary armament consisted of eighteen 15 cm (5.9 inch) SK L/40 guns and twelve 8.8 cm (3.45 in) SK L/30 quick-firing guns, all in individual mounts in casemates in the ship's hull and superstructure. The armament suite was rounded out with six 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes, all submerged in the hull; one was in the bow, another in the stern, and two on each broadside. The ship was protected with Krupp armor plate. In the central portion that protected her magazines and propulsion machinery spaces, her armored belt was 225 millimeters (8.9 in) thick, tapering to 100 mm (3.9 in) toward the bow and stern. The deck armor was 50 mm (2.0 in) thick. The main battery turrets had 250 mm (9.8 in) of armor plating.[7]

Service history

Construction – 1905

Wettin's keel was laid on 10 October 1899, at the Schichau-Werke in Danzig, under construction number 676. She was ordered under the contract name "D", as a new unit for the fleet.[7][8]Wettin was launched on 6 June 1901. King Albert of Saxony, a member of the House of Wettin, gave a speech at the ceremony. In August 1902, a crew of 60 men took the ship to Kiel for sea trials, which were supervised by KAdm Hunold von Ahlefeld. On 10 August, while at Swinemünde during the trials, Kaiser Wilhelm II reviewed Wettin from his yacht Hohenzollern. Wettin was commissioned on 1 October 1902, the first member of her class to enter service.[8][9] Further sea trials were completed by January 1903 and she joined I Squadron, replacing the battleship Weissenburg.[8] That year, the squadron was occupied with the normal peacetime routine of individual and unit training. This included a training cruise in the Baltic Sea followed by a voyage to Spain from 7 May to 10 June. In July, she embarked on the annual cruise to Norway with the rest of the squadron. The autumn maneuvers consisted of a blockade exercise in the North Sea, a cruise of the entire fleet to Norwegian waters, and a mock attack on Kiel ending on 12 September. The year's training schedule concluded with a cruise into the eastern Baltic that started on 23 November and a cruise into the Skagerrak that began on 1 December.[10]

Wettin and I Squadron participated in an exercise in the Skagerrak from 11 to 21 January 1904 and a further squadron exercise from 8 to 17 March. A major fleet exercise took place in the North Sea in May. In July, I Squadron and I Scouting Group visited Britain, including a stop at Plymouth on 10 July. The German ships sailed for the Netherlands on 13 July. I Squadron anchored in Vlissingen the following day, where they were visited by Queen Wilhelmina. The squadron remained in Vlissingen until 20 July, when it departed for a cruise in the northern North Sea with the rest of the fleet. The squadron stopped in Molde, Norway, on 29 July, while the other units went to other ports.[11] The fleet reassembled on 6 August and steamed back to Kiel, where it conducted a mock attack on the harbor on 12 August. During its cruise in the North Sea, the fleet experimented with wireless telegraphy on a large scale and with searchlights for night communication and recognition signals. Immediately after returning to Kiel, the fleet began preparations for the autumn maneuvers in the Baltic, which began on 29 August. The fleet moved to the North Sea on 3 September and took part in a major landing operation. The ships then embarked IX Corps ground troops that had participated in the exercises, transporting them to Altona for a parade before Wilhelm II. On 6 September, the ships conducted their own parade for the Kaiser off the island of Helgoland. Three days later, the fleet returned to the Baltic via the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal, where it participated in further landing operations with the IX Corps and the Guards Corps. On 15 September, the maneuvers came to an end.[12] I Squadron went on its winter training cruise, this time to the eastern Baltic from 22 November to 2 December.[13]

Wettin took part in training cruises with I Squadron from 9 to 19 January and 27 February to 16 March 1905.[13]Wettin was sent to assist her sister ship, Mecklenburg, which had run aground in the Great Belt on 3 March.[8] Individual and squadron training followed, with an emphasis on gunnery drills. On 12 July, the fleet began a major training exercise in the North Sea. It then cruised through the Kattegat and stopped at Copenhagen and Stockholm. The summer cruise ended on 9 August. The autumn maneuvers would normally have followed shortly thereafter but were delayed by a visit from the British Channel Fleet that month. The British fleet stopped in Danzig, Swinemünde, and Flensburg, where it was greeted by units of the German Navy. Wettin and the main German fleet were anchored at Swinemünde for the occasion. The visit was strained by the Anglo-German naval arms race, and the 1905 autumn maneuvers were shortened considerably, to just a week of exercises in the North Sea in early September. The first exercise presumed a naval blockade in the German Bight; the second envisioned a hostile fleet attempting to force the defenses of the Elbe.[14][15] In October, I Squadron went on a cruise in the Baltic. In early December, I and II Squadrons went on their regular winter cruise, this time to Danzig, where they arrived on 12 December. On the return trip to Kiel, the fleet conducted tactical exercises.[16]

1906–1914

The fleet undertook a heavier training schedule in 1906 than in previous years. The ships were occupied with individual, division and squadron exercises throughout April. Starting on 13 May, major fleet exercises took place in the North Sea and lasted until 8 June, with a cruise around the Skagen into the Baltic.[16] The fleet began its usual summer cruise to Norway in mid-July and was present for the birthday of Norwegian King, Haakon VII, on 3 August. The German ships departed the following day for Helgoland, to join exercises being conducted there. The fleet was back in Kiel by 15 August, where preparations for the autumn maneuvers began. Between 22 and 24 August, the fleet took part in landing exercises in Eckernförde Bay, outside Kiel. The maneuvers were paused on 31 August, when the fleet hosted vessels from Denmark and Sweden, which departed on 3 September. That same day, a Russian squadron visited in Kiel, remaining there until 9 September.[17] The maneuvers resumed on 8 September and lasted five more days.[18]

The ship participated in the uneventful winter cruise into the Kattegat and Skagerrak from 8 to 16 December. The first quarter of 1907 followed the previous pattern. On 16 February, the Active Battle Fleet was re-designated the High Seas Fleet. From the end of May to early June, the fleet went on its summer cruise in the North Sea, returning to the Baltic via the Kattegat. This was followed by the regular cruise to Norway from 12 July to 10 August. During the autumn maneuvers from 26 August to 6 September, the fleet conducted landing exercises in northern Schleswig with the IX Corps. The winter training cruise went into the Kattegat from 22 to 30 November. In May 1908, the fleet went on a major cruise into the Atlantic instead of its normal voyage in the North Sea. Stops included Horta, in the Azores. The fleet returned to Kiel on 13 August to prepare for the autumn maneuvers lasting from 27 August to 7 September. Division exercises in the Baltic followed from 7 to 13 September.[19] In early 1909, Wettin was rammed by the battleship Kaiser Karl der Grosse. She was not damaged in the accident and was able to continue training that year.[8] During the annual maneuvers, Wettin won the Kaiser's Schießpreis (Shooting Prize) for the best accuracy with her main battery among I Squadron ships. The year 1910 passed uneventfully for Wettin with a similar routine of training, exercises, and cruises as in previous years.[8]

By the time of the training exercises conducted in April, May, and June 1911, Wettin was the oldest battleship still in front-line service with the fleet. On 30 June her place in the squadron was taken by the new dreadnought battleship Thüringen. Wettin was reactivated on 1 December to replace her sister ship Schwaben, which needed a major overhaul after service as the fleet's gunnery training ship. In March and April 1912, Wettin, the armored cruiser Blücher, and the light cruisers Augsburg and Stuttgart were temporarily transferred from the artillery school to the Training Squadron. In August, Wettin was transferred from the artillery school to III Squadron where she took part in the annual fleet maneuvers.[8]

World War I

Map of the North and Baltic Seas in 1911

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Wettin was mobilized into IV Battle Squadron under the command of VAdm Ehrhard Schmidt.[20] IV Squadron also included her four sister ships and the battleships Elsass and Braunschweig. On 26 August, the ships were sent to rescue the stranded light cruiser Magdeburg, which had run aground off the island of Odensholm in the eastern Baltic, but the cruiser was scuttled by her crew before the relief force arrived. Wettin and the rest of the squadron returned to Bornholm that day.[21] Starting on 3 September, IV Squadron, assisted by Blücher, conducted a sweep into the Baltic. The operation lasted until 9 September but failed to bring Russian naval units to battle.[22]

Two days later, the ships were transferred to the North Sea. They stayed there only briefly, returning to the Baltic on 20 September. From 22 to 26 September, the squadron took part in a sweep into the eastern Baltic in an unsuccessful attempt to find and destroy Russian warships.[21] From 4 December 1914 to 2 April 1915, the ships of IV Squadron were tasked with coastal defense duties along Germany's North Sea coast, to prevent incursions by the British Royal Navy. Ships of the squadron's VII Division, which included Wettin, Wittelsbach, Schwaben, and Mecklenburg, then participated in training exercises in the western Baltic.[23]

The German Army requested naval assistance for its campaign against Russia. Prince Heinrich, the commander of all naval forces in the Baltic, made VII Division, IV Scouting Group, and the torpedo boats of the Baltic fleet available for the operation.[23][24] On 6 May, the VII Division ships were tasked with providing support for the assault on Libau. Wettin and the other ships were stationed off Gotland to intercept any Russian cruisers that might attempt to intervene in the landings, but the Russians took no such action.[25] When cruisers from the IV Scouting Group encountered Russian cruisers patrolling off Gotland, ships of the VII Division deployed, mounting a third dummy funnel to disguise them as the more powerful Braunschweig-class battleship. They were joined by the cruiser Danzig. The ships advanced as far as the island of Utö on 9 May and Kopparstenarna the following day, but by then the Russian cruisers had withdrawn.[23] Later that day, the British submarines HMS E1 and HMS E9 spotted IV Squadron but were too far away to attack.[25]

From 27 May to 4 July, Wettin was back in the North Sea, patrolling the mouths of the Jade, Ems, and Elbe rivers. During this period, the naval high command realized that the old Wittelsbach-class ships would be useless in action against the Royal Navy, but could be effectively used against the much weaker Russian forces in the Baltic. Consequently, the ships were transferred back to the Baltic in July. They departed Kiel on 7 July, bound for Danzig. On 10 July, the ships arrived in Neufahrwassar, Danzig along with the VIII Torpedo-boat Flotilla. IV Squadron ships sortied into the Baltic on 12 July to make a demonstration, returning to Danzig on 21 July without encountering Russian forces.[23]

Battle of the Gulf of Riga

The following month, the naval high command began an operation in the Gulf of Riga to support the Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive that the Army was waging. The Baltic naval forces were reinforced with significant elements of the High Seas Fleet, including I Battle Squadron, I Scouting Group, II Scouting Group, and II Torpedo-boat Flotilla. Prince Heinrich planned that Schmidt's ships would force their way into the Gulf and destroy the Russian warships at Riga, while the heavy units of the High Seas Fleet would patrol to the north to prevent interference by the main Russian Baltic Fleet. The Germans launched their attack on 8 August, initiating the Battle of the Gulf of Riga. Minesweepers attempted to clear a path through the Irbe Strait, covered by Braunschweig and Elsass, while Wettin and the rest of the squadron remained outside the strait. The Russian battleship Slava attacked the Germans in the strait, forcing them to withdraw.[23]

During the action, the cruiser Thetis and the torpedo boat S144 were damaged by mines. The torpedo boats T52 and T58 were mined and sunk. Schmidt withdrew his ships to re-coal. Prince Heinrich debated making another attempt, as the German Army's advance toward Riga had stalled. Nevertheless, Prince Heinrich tried to force the channel a second time with two dreadnought battleships from I Squadron to cover the minesweepers. Wettin was left at Libau[26] largely due to the scarcity of escorts. Increased activity by British submarines forced the Germans to employ more destroyers to protect their capital ships.[27]

Subsequent activity

On 9 September 1915, Wettin and her four sisters sortied in an attempt to locate Russian warships off Gotland, but returned to port two days later without having engaged any opponents. By this point in the war, the Navy was encountering difficulties in manning more important vessels.[26] Additionally, the threat from submarines in the Baltic convinced the German navy to withdraw the elderly Wittelsbach-class ships from active service.[28]Wettin and most of the other IV Squadron ships left Libau on 10 November, bound for Kiel. Arriving the next day, they were designated the Reserve Division of the Baltic, commanded by Kommodore (Commodore) Walter Engelhardt. The ships were anchored off Schilksee, Kiel. On 31 January 1916, the division was dissolved, and the ships were dispersed for subsidiary duties.[26]

Wettin was used as a training ship for naval cadets and as a depot ship for the remainder of the war. The ship was stricken from the naval register on 11 March 1920 and sold to ship breakers on 21 November 1921. Wettin was broken up for scrap the following year in Rönnebeck, a part of Bremen. Her bell is on display at the Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr in Dresden.[9]

Footnotes

Notes

^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

^ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick firing, while the L/40 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/40 gun is 40 caliber, meaning that the gun is 40 times as long as it is in diameter.[5]

Citations

^ Sondhaus, pp. 180–189, 216–218, 221–225.

^ Herwig, p. 43.

^ Gardiner, Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 248.

^ Gröner, pp. 16–17.

^ Grießmer, p. 177.

^ Hore, p. 67.

^ ab Gröner, p. 16.

^ abcdefg Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 8, p. 80.

^ ab Gröner, p. 17.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 5, pp. 48–51.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 5, pp. 51–52.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 5, p. 52.

^ ab Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 5, p. 54.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 5, pp. 54–55.

^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 134.

^ ab Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 5, p. 58.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 5, p. 59.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 5, p. 60.

^ Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 5, pp. 60–62.

^ Scheer, p. 15.

^ ab Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 8, p. 92.

^ Halpern, p. 185.

^ abcde Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 8, p. 93.

^ Scheer, pp. 90–91.

^ ab Halpern, p. 192.

^ abc Hildebrand, Röhr & Steinmetz Vol. 8, p. 94.

^ Halpern, p. 197.

^ Herwig, p. 168.

References

Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Volume 5) [The German Warships] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0456-9.

Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Volume 8) [The German Warships] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ASIN B003VHSRKE.

Hore, Peter (2006). The Ironclads. London: Southwater Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.

Scheer, Reinhard (1920). Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War. London: Cassell and Company. OCLC 2765294.

Sondhaus, Lawrence (1997). Preparing for Weltpolitik: German Sea Power Before the Tirpitz Era. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-745-7.