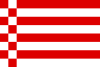

Bremen

Bremen | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Bremer Marktplatz, Bremen Hauptbahnhof, the Werdersee and the Town Musicians statue | |||

| |||

Location of Bremen | |||

Bremen Show map of Germany  Bremen Show map of Bremen | |||

| Coordinates: 53°5′N 8°48′E / 53.083°N 8.800°E / 53.083; 8.800Coordinates: 53°5′N 8°48′E / 53.083°N 8.800°E / 53.083; 8.800 | |||

| Country | Germany | ||

| State | Bremen | ||

| Government | |||

| • First Mayor | Carsten Sieling (SPD) | ||

| • Governing parties | SPD / Greens | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 326.73 km2 (126.15 sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 11,627 km2 (4,489 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 12 m (39 ft) | ||

| Population (2017-12-31)[1] | |||

| • City | 568,006 | ||

| • Density | 1,700/km2 (4,500/sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 2,400,000 | ||

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | ||

| Postal codes | 28001–28779 | ||

| Dialling codes | 0421 | ||

| Vehicle registration | HB (with 1 to 2 letters and 1 to 4 digits)[2] | ||

| Website | Bremen online | ||

The City Municipality of Bremen (German: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, IPA: [ˌʃtatɡəmaɪndə ˈbʁeːmən] (![]() listen)) is a Hanseatic city in northwestern Germany, which belongs to the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (also called just "Bremen" for short), a federal state of Germany.

listen)) is a Hanseatic city in northwestern Germany, which belongs to the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (also called just "Bremen" for short), a federal state of Germany.

As a commercial and industrial city with a major port on the River Weser, Bremen is part of the Bremen/Oldenburg Metropolitan Region, with 2.5 million people. Bremen is the second most populous city in Northern Germany and eleventh in Germany.[3]

Bremen is a major cultural and economic hub in the northern regions of Germany. Bremen is home to dozens of historical galleries and museums, ranging from historical sculptures to major art museums, such as the Übersee-Museum Bremen.[4] Bremen has a reputation as a working-class city.[5] Bremen is home to a large number of multinational companies and manufacturing centers. Companies headquartered in Bremen include the Hachez chocolate company and Vector Foiltec.[6] Four-time German football champions Werder Bremen are also based in the city. Werder Bremen share long feuds with the rival team in the neighbouring city of Hamburg, HSV with brawls at almost every match.

Bremen is some 60 km (37 mi) south of the mouth of the Weser on the North Sea. Bremen and Bremerhaven (at the mouth of the Weser) together comprise the state of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (official German name: Freie Hansestadt Bremen).

Contents

1 History

1.1 Advent of territorial power

1.2 Bremen and the Reformation

1.3 Thirty Years' War

1.3.1 Swedish reaction

1.4 19th century

1.5 20th century

2 Geography

2.1 Hills of Bremen

2.2 Climate

3 Demographics

4 Politics

4.1 Last state election

4.2 Administrative structure

5 Main sights

5.1 Structures

6 Economy

7 Transport

8 Events

9 Sports

10 Education and sciences

11 Miscellanea

12 Notable people

13 International relations

13.1 Twin and sister cities

13.2 Other relations

14 See also

15 References

15.1 Bibliography

15.2 Notes

16 External links

History

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled History of Bremen. (Discuss) (May 2017) |

Bremen, 16th century

The marshes and moraines near Bremen have been settled since about 12,000 BC. Burial places and settlements in Bremen-Mahndorf and Bremen-Osterholz date back to the 7th century AD. Since the Renaissance, some scientists have believed that the entry Fabiranum or Phabiranon in Ptolemy's Fourth Map of Europe,[7] written in AD 150, refers to Bremen. But Ptolemy gives geographic coordinates, and these refer to a site northeast of the mouth of the river Visurgis (Weser). In Ptolemy's time the Chauci lived in the area now called north-western Germany or Lower Saxony. By the end of the 3rd century, they had merged with the Saxons. During the Saxon Wars (772–804) the Saxons, led by Widukind, fought against the West Germanic Franks, the founders of the Carolingian Empire, and lost the war.

Charlemagne, the King of the Franks, made a new law, the Lex Saxonum, which forbid the Saxons worshipping Odin (the god of the Saxons); instead they had to convert to Christianity on pain of death. In 787 Willehad of Bremen became the first Bishop of Bremen. In 848 the archdiocese of Hamburg merged with the diocese of Bremen to become Hamburg-Bremen Archdiocese, with its seat in Bremen, and in the following centuries the archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen were the driving force behind the Christianisation of Northern Germany. In 888, at the behest of Archbishop Rimbert, Kaiser Arnulf of Carinthia, the Carolingian King of East Francia, granted Bremen the rights to hold its own markets, mint its own coins and make its own customs laws.

The city's first stone walls were built in 1032. Around that time trade with Norway, England and the northern Netherlands began to grow, thus increasing the importance of the city.

Germania, in the early 2nd century (Harper and Brothers, 1849)

View from the Bremen Cathedral in the direction of the Stephani-Bridge

In 1186 the Bremian Prince-Archbishop Hartwig of Uthlede and his bailiff in Bremen confirmed – without generally waiving the prince-archbishop's overlordship over the city – the Gelnhausen Privilege, by which Frederick I Barbarossa granted the city considerable privileges. The city was recognised as a political entity with its own laws. Property within the municipal boundaries could not be subjected to feudal overlordship; this also applied to serfs who acquired property, if they lived in the city for a year and a day, after which they were to be regarded as free persons. Property was to be freely inherited without feudal claims for reversion to its original owner. This privilege laid the foundation for Bremen's later status of imperial immediacy (Free Imperial City).

But in reality Bremen did not have complete independence from the Prince-Archbishops: there was no freedom of religion, and burghers still had to pay taxes to the Prince-Archbishops. Bremen played a double role: it participated in the Diets of the neighbouring Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen as part of the Bremian Estates and paid its share of taxes, at least when it had previously consented to this levy. Since the city was the major taxpayer, its consent was generally sought.[for what?] In this way the city wielded fiscal and political power within the Prince-Archbishopric, while not allowing the Prince-Archbishopric to rule in the city against its consent. In 1260 Bremen joined the Hanseatic League.

Advent of territorial power

14th to 18th century: territories of the Free City of Bremen (red) and of the Archbishopric of Bremen (yellow); straits between lower Weser and Jadebusen

In 1350, the number of inhabitants reached 20,000. Around this time the Hansekogge (cog ship) became a unique product of Bremen.

In 1362, representatives of Bremen rendered homage to Albert II, Prince-Archbishop of Bremen in Langwedel. In return, Albert confirmed the city's privileges and brokered a peace between the city and Gerhard III, Count of Hoya, who since 1358 had held some burghers of Bremen in captivity. The city had to bail them out. In 1365 an extra tax, levied to finance the ransom, caused an uprising among the burghers and artisans that was put down by the city council after much bloodshed.

In 1366, Albert II tried to take advantage of the dispute between Bremen's city council and the guilds, whose members had expelled some city councillors from the city. When these councillors appealed to Albert II for help, many artisans and burghers regarded this as a treasonous act, fearing that this appeal to the prince would only provoke him to abolish the autonomy of the city.

The fortified city maintained its own guards, not allowing soldiers of the Prince-Archbishop to enter it. The city reserved an extra very narrow gate, the so-called Bishop's Needle (Latin: Acus episcopi, first mentioned in 1274), for all clergy, including the Prince-Archbishop. The narrowness of the gate made it physically impossible for him to enter surrounded by his knights.

Nevertheless, on the night of 29 May 1366, Albert's troops, helped by some burghers, invaded the city. Afterward, the city had to again render him homage: the Bremen Roland, symbol of the city's autonomy, was destroyed; and a new city council was appointed. In return, the new council granted Albert a credit amounting to the then-enormous sum of 20,000 Bremen marks.

But city councillors of the previous council, who had fled to the County of Oldenburg, gained the support of the counts and recaptured the city on June 27, 1366. The members of the intermediate council were regarded as traitors and beheaded, and the city de facto regained its autonomy. Thereupon, the city of Bremen, which had for a long time held an autonomous status, acted almost completely independent of the Prince-Archbishop. Albert failed to obtain control over the city of Bremen a second time, since he was always short of money and lacked the support of his family, the Welfs, who were preparing for and fighting the Lüneburg War of Succession (1370–88).

By the end of the 1360s Bremen had provided credit to Albert II to finance his lavish lifestyle, and gained in return the fortress of Vörde along with the dues levied in its bailiwick as guarantee for the credit. In 1369 Bremen again lent money to Albert II against the collateral of his mint, which was from then on run by the city council, which took over his right to mint coins. In 1377 Bremen purchased from Duke Frederick I of Brunswick-Lüneburg many of the Prince-Archbishop's castles, which Albert had pledged as security for a loan to Frederick's predecessor. Thus Bremen gained a powerful position in the Prince-Archbishopric (ecclesiastical principality), in effect sidelining its actual ruler.

The declining knightly family of Bederkesa had become deeply indebted,[8]:29 and, having already sold many of their possessions, had even pawned half their say in the Bailiwick of Bederkesa (Amt Bederkesa) to the aspiring Mandelsloh family (a noble house, or Adelsgeschlecht). They lost the rest of their claims to the city of Bremen, when in 1381 its troops prevented the three Mandelsloh brothers from lending them to Albert II as territorial power.[8]:30 The Mandelslohs and other robber barons from the Prince-Bishopric of Verden and the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen ravaged burghers of the city of Bremen as well as inhabitants throughout the Prince-Archbishopric.

Bederkesa Castle, since 1381 a stronghold of Bremen's rural possessions within the Prince-Archbishopric, the later secularised Duchy of Bremen

In 1381 the city's troops successfully ended the brigandage and captured the Castle of Bederkesa and its bailiwick. Thus Bremen gained a foothold to uphold peace and order in its forecourt on the lower course of the Weser. In 1386 the city of Bremen became the liege lord of the noble families holding the estates of Altluneburg and Elmlohe, who had previously been vassals of the Knights of Bederkesa. The city replaced in 1404 the old wooden statue of Roland, which had been destroyed in 1366 by the Bederkesa, with a larger limestone model; this statue has managed to survive six centuries and two World Wars into the 21st.

In 1411 the jointly ruling dukes of Saxe-Lauenburg, Eric IV and his sons Eric V and John IV, pawned their share in the Bederkesa bailiwick and castle to the Senate of Bremen, including all "they have in the jurisdictions in the Frisian Land of Wursten and in Lehe (Bremerhaven), which belongs to the aforementioned castle and Vogtei".[9] Their share in jurisdiction, Vogtei (bailiwick) and castle had been acquired from the plague-stricken Knights of Bederkesa.[9] In 1421, Bremen acquired also the remaining half of the rights of the Bederkesa knights, including their remaining share in Bederkesa Castle.[8]:30

During the 1440s, Bremen was often in conflict with the Dutch states. The city began offering contracts to pirates to attack its enemies, and it became a regional hub of piracy. These pirates targeted foreign shipping around the North Sea and captured numerous vessels. One notorious captain, known as Grote Gherd ("Big Gerry"), captured 13 ships from Flanders in a single expedition.[10][11][12]

In 1648 the Prince-Archbishopric was transformed into the Duchy of Bremen, which was first ruled in personal union by the Swedish Crown. In November 1654, after the Second Bremian War, Bremen had to cede Bederkesa and the settlement of Lehe to the Duchy of Bremen (Treaty of Stade, 1654).

Bremen and the Reformation

Bremen town hall

When the Protestant Reformation swept through Northern Germany, St Peter's cathedral belonged to the cathedral immunity district (German: Domfreiheit; cf. also Liberty), an extraterritorial enclave of the neighbouring Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen. In 1532, the cathedral chapter which was still Catholic at that time closed St Peter's after a mob consisting of Bremen's burghers had forcefully interrupted a Catholic Mass and prompted a pastor to hold a Lutheran service.

In 1547, the chapter, which had in the meantime become predominantly Lutheran, appointed the Dutch Albert Rizaeus, called Hardenberg, as the first Cathedral pastor of Protestant affiliation. Rizaeus turned out to be a partisan of the Zwinglian understanding of the Lord's Supper, which was rejected by the then Lutheran majority of burghers, the city council, and chapter. So in 1561 – after heated disputes – Rizaeus was dismissed and banned from the city and the cathedral again closed its doors.

However, as a consequence of that controversy the majority of Bremen's burghers and city council adopted Calvinism by the 1590s, while the chapter, which was at the same time the body of secular government in the neighbouring Prince-Archbishopric, clung to Lutheranism. This antagonism between a Calvinistic majority and a Lutheran minority, though it had a powerful position in its immunity district (mediatised as part of the city in 1803), remained dominant until in 1873 the Calvinist and Lutheran congregations of Bremen were reconciled and founded a united administrative umbrella Bremen Protestant Church, which still exists today, comprising the bulk of Bremen's burghers.

At the beginning of the 17th century, Bremen continued to play its double role, wielding fiscal and political power within the Prince-Archbishopric, but not allowing the Prince-Archbishopric to rule in the city without its consent.

Thirty Years' War

Soon after the beginning of the Thirty Years' War Bremen declared its neutrality, as did most of the territories in the Lower Saxon Circle. John Frederick, Lutheran Administrator of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen, desperately tried to keep his Prince-Archbishopric out of the war, with the complete agreement of the Estates and the city of Bremen. When in 1623 the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, which was fighting in the Eighty Years' War for its independence against Habsburg's Spanish and imperial forces, requested its Calvinist co-religionist Bremen to join them, the city refused, but started to reinforce its fortifications.

In 1623 the territories comprising the Lower Saxon Circle decided to recruit an army in order to maintain an armed neutrality, since troops of the Catholic League were already operating in the neighbouring Lower Rhenish-Westphalian Circle and dangerously close to their region. The concomitant effects of the war, debasement of the currency and rising prices, had already caused inflation which was also felt in Bremen.

In 1623 the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, diplomatically supported by King James I of England, the brother-in-law of Christian IV of Denmark, started a new anti-Habsburg campaign. Thus the troops of the Catholic League were otherwise occupied and Bremen seemed relieved. But soon after this the imperial troops under Albrecht von Wallenstein headed north in an attempt to destroy the fading Hanseatic League, in order to reduce the Hanseatic cities of Bremen, Hamburg and the Lübeck and to establish a Baltic trade monopoly, to be run by some imperial favourites including Spaniards and Poles. The idea was to win Sweden's and Denmark's support, both of which had for a long time sought the destruction of the Hanseatic League.

In May 1625, Duke Christian IV of Holstein was elected – in the latter of his functions – by the Lower Saxon Circle's member territories commander-in-chief of the Lower Saxon troops. In the same year Christian IV joined the Anglo-Dutch military coalition. Christian IV ordered his troops to capture all the important traffic hubs in the Prince-Archbishopric and commenced the Battle of Lutter am Barenberge, on 27 August 1626, where he was defeated by the Leaguist troops under Johan 't Serclaes, Count of Tilly. Christian IV and his surviving troops fled to the Prince-Archbishopric and established their headquarters in Stade.

Roland

In 1627 Christian IV withdrew from the Prince-Archbishopric, in order to oppose Wallenstein's invasion of his Duchy of Holstein. Tilly then invaded the Prince-Archbishopric and captured its southern part. Bremen shut its city gates and entrenched itself behind its improved fortifications. In 1628, Tilly turned on the city, and Bremen paid him a ransom of 10,000 rixdollars in order to spare it a siege. The city remained unoccupied throughout the war.

The takeover by the Catholic League enabled Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor, to implement the Edict of Restitution, decreed March 6, 1629, within the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen including the city of Bremen. In September 1629 Francis William of Wartenberg, appointed by Ferdinand II as chairman of the imperial restitution commission for the Lower Saxon Circle, in carrying out the provisions of the Edict of Restitution, ordered the Bremian Chapter, seated in Bremen, to render an account of all the capitular and prince-archiepiscopal estates (not to be confused with the Estates). The Chapter refused, arguing first that the order had not been authorised and later that due to disputes with Bremen's city council, they could not freely travel to render an account, let alone do the necessary research on the estates. The anti-Catholic attitudes of Bremen's burghers and council was to make it completely impossible to prepare the restitution of estates from the Lutheran Chapter to the Roman Catholic Church. Even Lutheran capitulars were uneasy in Calvinistic Bremen.

Bremen's city council ordered that the capitular and prince-archiepiscopal estates within the boundaries of the unoccupied city were not to be restituted to the Catholic Church. The council argued that the city had long been Protestant, but the restitution commission replied that the city was de jure a part of the Prince-Archbishopric, so Protestantism had illegitimately taken over Catholic-owned estates. The city council replied that under these circumstances it would rather separate from the Holy Roman Empire and join the quasi-independent Republic of the Seven Netherlands.[13] The city was neither to be conquered nor to be successfully besieged due to its new fortifications and its access to the North Sea.

In October 1631 an army, newly recruited by John Frederick, started to reconquer the Prince-Archbishopric — helped by forces from Sweden and the city of Bremen. John Frederick returned to office, only to implement the supremacy of Sweden, insisting that it retain supreme command until the end of the war. With the impending enforcement of the military Major Power of Sweden over the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen, which was under negotiation at the Treaty of Westphalia, the city of Bremen feared it would fall under Swedish rule too. Therefore, the city appealed for an imperial confirmation of its status of imperial immediacy from 1186 (Gelnhausen Privilege). In 1646 Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor, granted the requested confirmation (Diploma of Linz) to the Free Imperial City.

Swedish reaction

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1350 | 20,000 | — |

| 1810 | 35,800 | +0.13% |

| 1830 | 43,700 | +1.00% |

| 1850 | 55,100 | +1.17% |

| 1880 | 111,900 | +2.39% |

| 1900 | 161,200 | +1.84% |

| 1925 | 295,000 | +2.45% |

| 1969 | 607,185 | +1.65% |

| 1995 | 549,357 | −0.38% |

| 1998 | 550,000 | +0.04% |

| 2001 | 540,950 | −0.55% |

| 2005 | 545,983 | +0.23% |

| 2006 | 546,900 | +0.17% |

| 2009[14] | 547,685 | +0.05% |

| 2012 | 548,319 | +0.04% |

| 2014[15] | 548,547 | +0.02% |

Territory of the Imperial City of Bremen on a late 18th century map

Nevertheless, Sweden, represented by its imperial fief Bremen-Verden, which comprised the secularised prince-bishoprics of Bremen and Verden, did not accept the imperial immediacy of the city of Bremen. Swedish Bremen-Verden tried to remediatise the Free Imperial City of Bremen (i.e., to make it switch its allegiance to Sweden). With this in view, Swedish Bremen-Verden twice waged war on Bremen. In 1381 the city of Bremen had imposed de facto rule in an area around Bederkesa and west of it as far as the lower branch of the Weser near Bremerlehe (a part of present-day Bremerhaven). Early in 1653, Bremen-Verden's Swedish troops captured Bremerlehe by force. In February 1654 the city of Bremen managed to get Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor, to grant it a seat and the vote in the Holy Roman Empire's Diet, thus accepting the city's status as Free Imperial City of Bremen.

Ferdinand III demanded that Christina of Sweden, Duchess regnant of Bremen-Verden, compensate the city of Bremen for the damages caused and restitute Bremerlehe. When in March 1654 the city of Bremen started to recruit soldiers in the area of Bederkesa, in order to prepare for further arbitrary acts, Swedish Bremen-Verden enacted the First Bremian War (March to July 1654), arguing that it was acting in self-defence. The Free Imperial City of Bremen had meanwhile urged Ferdinand III to support it, who in July 1654 asked Charles X Gustav of Sweden, Christina's successor as Duke of Bremen-Verden, to cease the conflict, which resulted in the First Stade Recess (November 1654). This treaty left the main issue, the acceptance of the city of Bremen's imperial immediacy, unresolved. But the city agreed to pay tribute and levy taxes in favour of Swedish Bremen-Verden and to cede its possessions around Bederkesa and Bremerlehe, which was why it was later called Lehe.

In December 1660 the city council of Bremen rendered homage as Free Imperial City of Bremen to Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor. In 1663 the city gained a seat and a vote in the Imperial Diet, despite sharp protest from Swedish Bremen-Verden. In March 1664 the Swedish Diet came out in favour of waging war on the Free Imperial City of Bremen. Right after Leopold I, who was busy with wars against the Ottoman Empire, had enfeoffed the minor King Charles XI of Sweden with Bremen-Verden, while the neighbouring Brunswick and Lunenburg-Celle was occupied by succession quarrels and France not opposed, Sweden started the Second Bremian War (1665–66) from its Bremen-Verden fief.

The Swedes under Carl Gustaf Wrangel laid siege to the city of Bremen. The siege brought Brandenburg-Prussia, Brunswick and Lunenburg-Celle, Denmark, Leopold I and the Netherlands onto the scene, who were all in favour of the city, with Brandenburgian, Cellean, Danish, and Dutch troops at Bremen-Verden's borders ready to invade. So on 15 November 1666 Sweden had to sign the Treaty of Habenhausen, obliging it to destroy the fortresses built close to Bremen and banning Bremen from sending its representative to the Diet of the Lower Saxon Circle. From then on no further Swedish attempts were made to capture the city.

In 1700 Bremen introduced – like all Protestant territories of imperial immediacy – the Improved Calendar, as it was called by Protestants, in order not to mention the name of Pope Gregory XIII. So Sunday, 18 February of Old Style was followed by Monday, 1 March New Style.

19th century

Territory of the Free City of Bremen since 1800

The harbour of Vegesack became part of the city of Bremen in 1803. In 1811, Napoleon invaded Bremen and integrated it as the capital of the Département de Bouches-du-Weser (Department of the Mouths of the Weser) into the French State. In 1813, the French – as they retreated – withdrew from Bremen. Johann Smidt, Bremen's representative at the Congress of Vienna, was successful in achieving the non-mediatisation of Bremen, Hamburg and Lübeck, by which they were not incorporated into neighbouring monarchies, but became sovereign republics. Bremen joined the North German Confederation in 1867 and four years later became an autonomous component state of the new-founded German Empire and its successors.

The first German steamship was manufactured in 1817 in the shipyard of Johann Lange. In 1827, Bremen, under Johann Smidt, its mayor at that time, purchased land from the Kingdom of Hanover, to establish the city of Bremerhaven (Port of Bremen) as an outpost of Bremen because the river Weser was silting up. The shipping company Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL) was founded in 1857. Lloyd was a byword for commercial shipping and is now a part of Hapag-Lloyd.

Beck's Brewery was founded in 1837 and remains in operation today as part of Anheuser-Busch InBev. In 1872, the Bremen Cotton Exchange was founded.

20th century

The Soviet Republic of Bremen existed from January to February 1919 in the aftermath of World War I, before it was overthrown by Gerstenberg Freikorps.

Proclamation of the Revolutionary Republic of Bremen (Bremer Räterepublik) in front of the town hall, 15 November 1918

Henrich Focke, Georg Wulf and Werner Naumann founded Focke-Wulf Flugzeugbau AG in Bremen in 1923; the aircraft construction company as of 2010[update] forms part of Airbus,[citation needed] a manufacturer of civil and military aircraft. Borgward, an automobile manufacturer, was founded in 1929, and is today part of Daimler AG.

The villages of Grohn, Schönebeck, Aumund, Hammersbeck, Fähr, Lobbendorf, Blumenthal, Farge and Rekum became part of the city of Bremen in 1939. The Bremen-Vegesack concentration camp operated during World War II.

Allied bombing destroyed 60% of the built up area of Bremen during World War II.[16] The British 3rd Infantry Division under General Whistler captured Bremen in late April 1945.[17]

In 1946 Bremen's mayor Wilhelm Kaisen (SPD) travelled to the U.S. to re-establish Bremen's statehood, as Bremen had traditionally been a city-state, in order to prevent its incorporation into the state of Lower Saxony in the British zone of occupation. In 1947 the city became an enclave, part of the American occupation zone surrounded by the British zone.

In 1947, Martin Mende founded Nordmende, a manufacturer of entertainment electronics. The company existed until 1987. OHB-System, a manufacturer of medium-sized space-flight satellites, was founded in 1958.

The University of Bremen, founded in 1971, is one of 11 institutions classed as an "Elite university" in Germany, and teaches approximately 23,500 people from 126 countries.

Geography

Bremen's city hall, cathedral and Bürgerschaft

View from the Stephanibrücke towards the city centre and cathedral

Bremen lies on both sides of the River Weser, about 60 kilometres (37 miles) upstream of its estuary on the North Sea and its transition to the Outer Weser by Bremerhaven. Opposite Bremen's Altstadt is the point where the "Middle Weser" becomes the "Lower Weser" and, from the area of Bremen's port, the river has been made navigable to ocean-going vessels. The region on the left bank of the Lower Weser, through which the Ochtum flows, is the Weser Marshes, the landscape on its right bank is part of the Elbe-Weser Triangle. The Lesum, and its tributaries, the Wümme and Hamme, the Schönebecker Aue and Blumenthaler Aue, are the downstream tributaries of the Weser.

The city's municipal area is about 38 kilometres (24 miles) long and 16 kilometres (10 miles) wide. In terms of area, Bremen is the thirteenth largest city in Germany; and in terms of population the second largest city in northwest Germany after Hamburg and the tenth largest in the whole of Germany (see: List of cities in Germany).

Bremen lies about 50 kilometres (31 miles) east of the city of Oldenburg, 110 kilometres (68 miles) southwest of Hamburg, 120 kilometres (75 miles) northwest of Hanover, 100 kilometres (62 miles) north of Minden and 105 kilometres (65 miles) northeast of Osnabrück. Part of Bremerhaven's port territory forms an exclave of the City of Bremen.

Hills of Bremen

The inner city lies on a Weser dune, which reaches a natural height of 10.5 m above sea level (NN) at Bremen Cathedral; its highest point, though, is 14.4 m above sea level (NN) and lies to the east at the Polizeihaus, Am Wall 196. The highest natural feature in the city of Bremen is 32.5 m above NN and lies in Friedehorst Park in the northwestern borough of Burglesum.[18]:25 As a result, Bremen has the lowest high point of all the German states.[19] However, the man-made tip of the rubbish dump Blockland-Deponie in Bremen-Walle is higher at 49 m above NN.

Climate

Bremen has a moderate oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb) due to its proximity to the North Sea coast and temperate maritime air masses that move in with the predominantly westerly winds from the Atlantic Ocean. However, periods in which continental air masses predominate may occur at any time of the year and can lead to heat waves in the summer and prolonged periods of frost in the winter. In general though, extremes are rare in Bremen and temperatures below −15 °C (5.0 °F) and above 35 °C (95.0 °F) occur only once every couple of years. The record high temperature was 37.6 °C (99.7 °F) on 9 August 1992, while the official record low temperature was −23.6 °C (−10.5 °F) on 13 February 1940.[20] However, the astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers reported to have measured −27,3 °C on 23. January 1823.[21] Being at some distance from the main North Sea, Bremen still has a somewhat wider temperature range than Bremerhaven that is located on the mouth of Weser.

Average temperatures have risen continually over the last decades, leading to a 0.6 °C (1.1 °F) rise in the mean annual temperature between 1961–90 and 1981–2010 reference periods. As in most parts of Germany, the year 2014 has been the warmest year on record averaging 11.1 °C (52.0 °F), making Bremen the second-warmest German state after Berlin in 2014.[22] While Bremen is located in the comparatively cloudy northwestern part of Germany, there has been a significant increase in average sunshine hours over the last decades, especially in the months of April, May and July, causing the annual mean to rise by 62 hours between the two reference periods mentioned above.[23] This trend has continued over the last 10 years, which average 1614 hours of sunshine, a good 130 hours more than in the international reference period of 1961–90.[24] Nevertheless, especially the winters remain extremely gloomy by international standards with December averaging hardly more than one hour of sunshine (out of 7 astronomically possible) per day, a feature that Bremen shares with most of Germany and its neighbouring countries, though.

Precipitation is distributed fairly even around the year with a small peak in summer mainly due to convective precipitation, i.e. showers and thunderstorms. Snowfall and the period of snow cover are variable; whereas in some years, hardly any snow accumulation occurs, there has recently been a series of unusually snowy winters, peaking in the record year 2010 counting 84 days with a snow cover.[25] Nevertheless, snow accumulation of more than 20 centimetres (8 in) remains exceptional, the record being 68 centimetres (26.8 in) of snow on 18 February 1979.

The warmest months in Bremen are June, July, and August, with average high temperatures of 20.2 to 22.6 °C (68.4 to 72.7 °F). The coldest are December, January, and February, with average low temperatures of −1.1 to 0.3 °C (30.0 to 32.5 °F). Typical of its maritime location, autumn tends to remain mild well into October, while spring arrives later than in the southwestern parts of the country.

| Climate data for Bremen | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.6 (58.3) | 18.5 (65.3) | 23.5 (74.3) | 30.2 (86.4) | 34.4 (93.9) | 34.9 (94.8) | 36.8 (98.2) | 37.6 (99.7) | 33.4 (92.1) | 28.6 (83.5) | 20.1 (68.2) | 16.1 (61.0) | 37.6 (99.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.9 (39.0) | 4.8 (40.6) | 8.7 (47.7) | 12.8 (55.0) | 18.0 (64.4) | 20.2 (68.4) | 22.4 (72.3) | 22.6 (72.7) | 18.4 (65.1) | 13.5 (56.3) | 8.0 (46.4) | 5.1 (41.2) | 13.2 (55.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) | 1.9 (35.4) | 5.0 (41.0) | 8.1 (46.6) | 12.7 (54.9) | 15.3 (59.5) | 17.4 (63.3) | 17.4 (63.3) | 13.9 (57.0) | 9.7 (49.5) | 5.2 (41.4) | 2.7 (36.9) | 9.2 (48.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.1 (30.0) | −1.1 (30.0) | 1.3 (34.3) | 3.4 (38.1) | 7.4 (45.3) | 10.3 (50.5) | 12.4 (54.3) | 12.1 (53.8) | 9.3 (48.7) | 5.8 (42.4) | 2.3 (36.1) | 0.3 (32.5) | 5.2 (41.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −21.8 (−7.2) | −23.6 (−10.5) | −18.7 (−1.7) | −7.6 (18.3) | −3.5 (25.7) | 0.5 (32.9) | 3.0 (37.4) | 3.4 (38.1) | −1.2 (29.8) | −7.8 (18.0) | −14.1 (6.6) | −17.5 (0.5) | −23.6 (−10.5) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 55.1 (2.17) | 35.6 (1.40) | 51.2 (2.02) | 40.8 (1.61) | 54.2 (2.13) | 73.4 (2.89) | 65.0 (2.56) | 61.2 (2.41) | 60.1 (2.37) | 55.4 (2.18) | 57.7 (2.27) | 61.6 (2.43) | 671.3 (26.43) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11.3 | 8.6 | 11.0 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 10.8 | 10.1 | 10.6 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 12.0 | 126 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87 | 84 | 80 | 75 | 71 | 73 | 75 | 75 | 81 | 84 | 87 | 88 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 47 | 71 | 107 | 170 | 214 | 193 | 205 | 193 | 143 | 108 | 54 | 40 | 1,545 |

| Source: DWD; wetterkontor.de;[26][27] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

As of 2015[update], Bremen had a population of 557,464 of whom about 89,713 (16%) had foreign citizenship.[18]:39 Furthermore, 29.4% of the city population were of non-German origin/ethnicity as of 2015.[28]

Number of minorities in Bremen by nationality as of 31 December 2015:[18]:39

| Rank | Nationality | Population (31.12.2017) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20,805 | |

| 2 | 11,545 | |

| 3 | 8,315 | |

| 4 | 5,950 | |

| 5 | 2,890 |

Politics

The Stadtbürgerschaft (municipal assembly) is made up of 68 of the 83 legislators of the state legislature, the Bremische Bürgerschaft, who reside in the city of Bremen. The legislature is elected by the citizens of Bremen every four years.

Bremen has a reputation as a Left-wing city. This left wing atmosphere largely stems from a transition from an industrial economy to a service economy.[29] In elections for the Stadtbürgerschaft, the Social Democratic Party has dominated for decades. The Greens have also been very successful in city elections. The state of Bremen, which consists of the city, is governed by a coalition of the Social Democratic Party and The Greens.

One of the two mayors (Bürgermeister) is elected President of the Senate (Präsident des Senats) and serves as head of the city and the state. The current president is Carsten Sieling

Last state election

| Party | Votes | % | +/– | Seats | +/– | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 32.9 | 30 | ||||

Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 22.4 | 20 | ||||

Alliance '90/The Greens | 15.1 | 14 | ||||

The Left | 9.5 | 8 | ||||

Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 6.5 | 6 | ||||

Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 5.5 | N/A | 4 | N/A | ||

Citizens in Rage (BIW) | 3.2 | 1 | ||||

The Party | 1.9 | N/A | 0 | N/A | ||

Pirate Party Germany (PIRATEN) | 1.5 | 0 | ||||

Human Environment Animal Protection (The Animal Protection Party) | 1.2 | N/A | 0 | N/A | ||

National Democratic Party (NPD) | 0.2 | 0 | ||||

Totals | 100.0% | — | 83 | — | ||

Provisional results; the AfD did not reach the 5% threshold in Bremerhaven (and will hence only receive seats for votes from Bremen), the BIW did not reach the threshold in Bremen (and will only receive one seat in Bremerhaven, none in Bremen).[30][31]

Administrative structure

| Stadtbezirk (borough) | Stadtteile (urban districts), Ortsteile (subdistricts, selectively) | Area | Population | Density of population | Maps | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mitte (Central) 1 |

| 33.741 km² | 17,392 | 515 / km² |  Mitte |  Häfen |

Süd (South) 2 |

Neustadt, Südervorstadt and Gartenstadt Süd between Alte Neustadt and the airport city

| 66.637 km² | 123,303 | 1,850 / km² |  Neustadt  Huchting  Seehausen |  Obervieland  Woltmershausen  Strom |

Ost (East) 3 |

| 108.201 km² | 218,843 | 2,023 / km² |  Östliche Vorstadt  Vahr  Borgfeld  Osterholz |  Schwachhausen  Horn-Lehe  Oberneuland  Hemelingen |

West 4 |

| 56.606 km² | 89,216 | 1,576 / km² |  Blockland  Findorff |  Walle  Gröpelingen |

Nord (North) 5 |

| 60.376 km² | 98,606 | 1,633 / km² |  Burglesum  Blumenthal |  Vegesack |

Main sights

- Many of the sights in Bremen are found in the Altstadt (Old Town), an oval area surrounded by the Weser River, on the southwest, and the Wallgraben, the former moats of the medieval city walls, on the northeast. The oldest part of the Altstadt is the southeast half, starting with the Marktplatz and ending at the Schnoor quarter.

- The Marktplatz (Market square) is dominated by the opulent façade of the Town Hall of Bremen. The building was erected between 1405 and 1410 in Gothic style, but the façade was built two centuries later (1609–12) in Renaissance style. The Town Hall is the seat of the president of the Senate of Bremen. Today, it hosts a restaurant in original decor with gigantic wine barrels, the Ratskeller in Bremen, and the wine lists boasts more than 600 – exclusively German – wines. It is also home of the twelve oldest wines in the world, stored in their original barrels in the Apostel chamber. In July 2004, along with the Bremen Roland, the building was added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

- Two statues stand to the west side of the Town Hall: one is the statue Bremen Roland (1404) of the city's protector, Roland, with his view against the Cathedral and bearing Durendart, the "sword of justice" and a shield decorated with an imperial eagle. The other near the entrance to the Ratskeller is Gerhard Marcks' bronze sculpture (1953) Die Stadtmusikanten (Town Musicians), which portrays the donkey, dog, cat and rooster of the Grimm Brothers' fairy tale.

- Other interesting buildings in the vicinity of the Marktplatz are the Schütting, a 16th-century Flemish-inspired guild hall, Rathscafé, Raths-Apotheke, Haus der Stadtsparkasse and the Stadtwaage, the former weigh house (built in 1588), with an ornate Renaissance façade, and the nearby Essighaus, once a fine Renaissance town house. The façades and houses surrounding the market square were the first buildings in Bremen to be restored after World War II, by the citizens of Bremen themselves.

- St Peter's Cathedral (13th century), to the east of the Marktplatz, with sculptures of Moses and David, Peter and Paul and Charlemagne. The Bismark Monument is also outside the cathedral, which is the only monument in Germany to depict Otto von Bismark in an equestrian format.

- On Katherinenklosterhof to the northwest of the cathedral, a few remaining traces can be found of St Catherine's Monastery dating back to the 13th century.

- The Liebfrauenkirche (Our Lady's Church) is the oldest church of the town (11th century). Its crypt features several impressive murals from the 14th century.

- Off the south side of the Markplatz, the 110 m (120 yd) Böttcherstraße was transformed in 1923–1931 by the coffee magnate Ludwig Roselius, who commissioned local artists to convert the narrow street (in medieval times, the street of the barrel makers) into an inspired mixture of Gothic and Art Nouveau. It was considered "entartete Kunst" (degenerate art) by the Nazis. Today, the street is one of Bremen's most popular attractions, with the Glockenspiel House at No. 4 with its carillon of Meissen porcelain bells.[32]

- At the end of Böttcherstraße, by the Weser bank, stands the Martinikirche (St Martin's Church), a Gothic brick church built in 1229, and rebuilt in 1960 after its destruction in World War II.[33]

- Tucked away between the Cathedral and the river is the Schnoor, a small, well-preserved area of crooked lanes, fishermen's and shipper's houses from the 17th and 18th centuries, now occupied by cafés, artisan shops and art galleries. The Convent of Saint Birgitta (Birgittenkloster) founded in 2002 is a small community of just seven nuns offering guest accommodation.[34]

Schlachte, the medieval harbour of Bremen (the modern port is some kilometres downstream) and today a riverside boulevard with pubs and bars aligned on one side and the banks of Weser on the other.[35]

- The Viertel district to the east of the old town combines rows of 19th-century Bremen houses (Bremer Häuser) with museums and the theatres of Theater Bremen along the city's cultural mile (Kulturmeile (Bremen)).[36]

- The Nasir Moschee is the first purpose built mosque of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in Bremen.[37]

More contemporary tourist attractions include:

Universum Science Center, a modern science museum- The Rhododendron-Park Bremen, a major collection of rhododendrons and azaleas; also includes a botanical garden

Botanika, a nature museum within the Rhododendron-Park Bremen that attempts be to the same as the Universum, but for biology

Beck's Brewery, tours are available to the public which include beer tasting

- The Kunsthalle Bremen, an art museum with paintings from the 19th and 20th century, maintained by the citizens of Bremen

- Focke Museum,[38] museum of art and cultural history

- The Übersee Museum Bremen (Overseas (World) Museum) is a natural history and ethnographic museum near by the Central Station Bremen.

- The Kunstsammlungen Böttcherstraße, an art museum in expressionist architecture from Bernhard Hoetger with paintings from the 20th century from Paula Modersohn-Becker

- The Weserburg Museum für moderne Kunst ("Weserburg Modern Art Museum"), a modern art museum located in the middle of the Weser River[39]

View from the Stephani-Bridge in the direction of the Cathedral

Schlachte

Baumwollbörse (Cotton exchange)

The Parkhotel in the Bürgerpark (central park)

Musical-Theater

Central Park Wallanlagen

The city hall (Rathaus)

Swineherd and pigs sculpture in Bremen

The Weser River in Bremen

A building on Böttcherstraße

Bremer Bank

Central Bremen and the Weser from St. Petri Dom

Bremen Airport

The skyscraper Weser Tower designed by Helmut Jahn

Böttcherstraße

Schnoor

Beck & Co

Bremen-Arena

Structures

The Fallturm (Drop Tower) of the University of Bremen

- Mediumwave transmitter Bremen

- Fallturm Bremen

- Bremen-Walle Telecommunication Tower

The Freie Waldorfschule in Bremen-Sebaldsbrück was Germany's first school built to the Passivhaus low-energy building standard.[40]

Economy

According to data from the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development, Bremen had a GDP per capita of $53,379 in 2013, higher than the average for Germany as a whole. For comparison, in 2013, the World Bank reported Germany had a GDP per capita of $46,268, and the EU overall had a GDP per capita of $35,408 in the same year.[41]

Bremen is the second development centre of the region, after Hamburg. It forms part of the production network of Airbus SAS and this is where equipping of the wing units for all widebody Airbus aircraft and the manufacture of small sheet metal parts takes place. Structural assembly, including that of metal landing flaps, is another focal point. Within the framework of Airbus A380 production, assembly of the landing flaps (high lift systems) is carried out here. The pre-final assembly of the fuselage section (excluding the cockpit) of the A400M military transport aircraft takes place before delivery on to Spain.[42]

More than 3,100 persons are employed at Airbus Bremen, the second largest Airbus site in Germany. As part of the Centre of Excellence – Wing/Pylon, Bremen is responsible for the design and manufacture of high-lift systems for the wings of Airbus aircraft. The entire process chain for the high-lift elements is established here, including the project office, technology engineering, flight physics, system engineering, structure development, verification tests, structural assembly, wing equipping and ultimate delivery to the final assembly line. In addition, Bremen manufactures sheet metal parts like clips and thrust crests for all Airbus aircraft as part of the Centre of Excellence – Fuselage and Cabin.[43]

In Bremen there is a plant of EADS Astrium and the headquarters of OHB-System, respectively the first and the third space companies of European Union.

There is also a Mercedes-Benz factory in Bremen, building the C, CLK, SL, SLK, and GLK series of cars.[44]

Beck & Co's headlining brew Beck's and St Pauli Girl beers are brewed in Bremen. In past centuries when Bremen's port was the "key to Europe", the city also had a large number of wine importers, but the number is down to a precious few. Apart from that there is another link between Bremen and wine: about 800 years ago, quality wines were produced here. The largest wine cellar in the world is located in Bremen (below the city's main square), which was once said to hold over 1 million bottles, but during WWII was raided by occupying forces.

A large number of food producing or trading companies are located in Bremen with their German or European headquarters: Anheuser-Busch InBev (Beck's Brewery), Kellogg's, Kraft Foods (Kraft, Jacobs Coffee, Milka Chocolate, Milram, Miràcoli), Frosta (frosted food), Nordsee (chain of sea fast food), Melitta Kaffee, Eduscho Kaffee, Azul Kaffee, Vitakraft (pet food for birds and fishes), Atlanta AG (Chiquita banana), chocolatier Hachez (fine chocolate and confiserie), feodora chocolatier.

Bremer Woll-Kämmerei (BWK), a worldwide operating company for manufacturing wool and trading in wool and similar products, is headquartered in Bremen.

Transport

Bremen Central Station

Map of the Bremen S-Bahn

Bremen has an international airport situated 3 km (2 mi) south of the city centre.

Trams in Bremen and local bus services are offered by the Bremer Straßenbahn AG (translates from German as Bremen Tramways Corporation), often abbreviated BSAG, the public transport provider for Bremen.[45]

The Bremen S-Bahn covers the Bremen/Oldenburg Metropolitan Region, from Bremerhaven in the north to Twistringen in the south and from Oldenburg in the west, centred on Bremen Central Station. It has been in operation since 2010.[46] This network unified existing regional transport in Bremen as well as surrounding cities, including Bremerhaven, Delmenhorst, Twistringen, Nordenham, Oldenburg, and Verden an der Aller. The network lies completely within the area of the Bremen-Lower Saxony Transport Association, whose tariff structure applies.

Events

- On August 8 1992, in Weserstadion, Michael Jackson performed a show as part of his Dangerous World Tour.It was one of his three shows in Bremen and on his next and last tour he kicked off the next tour History World Tour in Bremen.

- Every year since 1036, in the last two weeks of October, Bremen has hosted the Freimarkt ("Free market"), one of the world's oldest and in Germany one of today's biggest continuously celebrated fairground festivals.

- Bremen is host to one of the four big annual Techno parades, the Vision Parade.

- Bremen is also host of the "Bremer 6 Tage Rennen" a bicycle race at the Bremen Arena.

- Every year the city plays host to young musicians from across the world, playing in the International Youth Symphony Orchestra of Bremen (IYSOB).

- On March 12, 1999, the rock band Kiss played a live show in Bremen. Before the show, they were told by the fire marshall not to use any fireworks. They did not use any fireworks until the very end, when they set off all of the fireworks at once. Because of this, they are now banned from playing in Bremen.

- Bremen was host to the 2006 RoboCup competition.

- Bremen was host to the 32nd Deutscher Evangelischer Kirchentag, 20–24 May 2009.

- Bremen hosted the 50th International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) from 10–22 July 2009.[47]

Sports

Weser-Stadion is the home ground of Werder Bremen

Bremen is home to the football team Werder Bremen, who won the German Football Championship for the fourth time and the German Football Cup for the fifth time in 2004, making them only the fourth team in German football history to win the double; the club won the German Football Cup for the sixth time in 2009. Only Bayern Munich has won more titles. In the final match of the 2009–10 season, Werder Bremen lost to Bayern Munich. The home stadium of SV Werder Bremen is the Weserstadion, a pure football stadium, almost completely surrounded by solar cells. It is one of the biggest buildings in Europe delivering alternative energy.

Education and sciences

With 18000 students,[48] the University of Bremen is the largest university in Bremen, and is also home to the international Goethe-Institut and the Fallturm Bremen. Additionally, Bremen has a University of the Arts and the Bremen University of Applied Sciences. In 2001, the private Jacobs University Bremen was founded. All major German research foundations maintain institutes in Bremen, with a focus on marine sciences: The Max Planck Society with the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, and the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Scientific Community with the Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (zmt).[49] The Bremerhaven-based Alfred-Wegener-Institute of the Helmholtz Association closely cooperates with the aforementioned institutes, especially within the MARUM[50] a center for marine environmental sciences, affiliated to the University of Bremen. Furthermore, The Fraunhofer Society is present in Bremen with centers for applied material research (IFAM[51]) and medical image computing (MEVIS[52]).

Miscellanea

- In December 1949, Bremen hosted the lecture cycle Einblick in das, was ist by the philosopher Martin Heidegger, in which Heidegger introduced his concept of a "fourfold" of earth and sky, gods and mortals. This was also Heidegger's first public-speaking engagement following his removal from his Freiburg professorship by the Denazification authorities.

- Bremen is connected with a fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm, the Town Musicians of Bremen, although they never actually reach Bremen in the tale.

- The 1922 film Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens was set mostly in Bremen.

Notable people

International relations

Twin and sister cities

Bremen is twinned with:[53]

Gdańsk, Poland, since 1976[53][54]

Gdańsk, Poland, since 1976[53][54]

Riga, Latvia, since 1985[53][55]

Riga, Latvia, since 1985[53][55]

Dalian, People's Republic of China, since 1985[53]

Dalian, People's Republic of China, since 1985[53]

Rostock, Germany, since 1987[53]1

Rostock, Germany, since 1987[53]1

Haifa, Israel, since 1988[53]

Haifa, Israel, since 1988[53]

İzmir, Turkey, since 1995[53]

İzmir, Turkey, since 1995[53]

Lukavac, Bosnia and Herzegovina, since 1996[53]

Lukavac, Bosnia and Herzegovina, since 1996[53]

Durban, South Africa, since 2011[53][56]

Durban, South Africa, since 2011[53][56]

Maracaibo, Venezuela

Maracaibo, Venezuela

^1 Then German Democratic Republic

Other relations

"Informal" relationships:

Pune, India[53][57][58][59]

Pune, India[53][57][58][59]

Dudley, United Kingdom[53][60]

Dudley, United Kingdom[53][60]

Windhoek, Namibia[53]

Windhoek, Namibia[53]

Tamra, Israel

Tamra, Israel

See also

- List of mayors of Bremen

References

Bibliography

Tristam Carrington-Windo, Katrin M. Kohl (1998). A Dictionary of Contemporary Germany. Routledge (UK). p. page 64. ISBN 1-57958-114-5..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

[dead link]}- Claus Christian (2007): A photographic excursion through Bremen, Bremen-North, Bremerhaven, Fischerhude and Worpswede,

ISBN 978-3-00-015451-5

Dannenberg, Hans-Eckhard; Schulze, Heinz-Joachim (1995). Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser vol. 1 Vor- und Frühgeschichte. Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden. ISBN 978-3-9801919-7-5.

Dannenberg, Hans-Eckhard; Schulze, Heinz-Joachim (1995). Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser vol. 2 Mittelalter (einschl. Kunstgeschichte). Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden. ISBN 978-3-9801919-8-2.

Dannenberg, Hans-Eckhard; Schulze, Heinz-Joachim (2008). Geschichte des Landes zwischen Elbe und Weser vol. 3 Neuzeit. Stade: Landschaftsverband der ehem. Herzogtümer Bremen und Verden. ISBN 978-3-9801919-9-9.

- Herbert Schwarzwälder (1995), Geschichte der Freien Hansestadt Bremen. Vol. I – V. Bremen: Edition Temmen,

ISBN 3-86108-283-7

Notes

^ "Bevölkerung, Gebiet - Aktuelle Statistische Berichte - Bevölkerungsentwicklung im Land Bremen". Statistisches Landesamt Bremen (in German). September 2018.

^ The carsign HB with 1 letter and 4 digits is reserved for vehicle registration in Bremerhaven.

^ "Germany: States and Major Cities – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

^ "Museums and Galleries – bremen.de". www.bremen.de. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

^ "Bremen city report". Retrieved 2015-08-28.

[dead link]

^ "Bremen – Made in Bremen". www.bremen.de. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

^ "DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT • LacusCurtius • Ptolemy's Geography — Book II, Chapter 10 • DRAFT DRAFT DRAFT". uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

^ abc Otto Edert, Neuenwalde: Reformen im ländlichen Raum, Norderstedt: Books on Demand, 2010.

ISBN 978-3-8391-9479-9.

^ ab In the Middle Low German original: "wes zee hebben an gherichte in Vreslande . . . unde an Lee, dat to deme vorscrevenen slote unde voghedie höret", here after Bernd Ulrich Hucker, "Die landgemeindliche Entwicklung in Landwürden, Kirchspiel Lehe und Kirchspiel Midlum im Mittelalter" (first presented in 1972 as a lecture at a conference of the historical work study association of the northern Lower Saxon Landschaftsverbände held at Oldenburg in Oldenburg), in: Oldenburger Jahrbuch, vol. 72 (1972), pp. 1—22, here p. 13.

^ "Bremen Piracy and Scottish Periphery: The North Sea World in the 1440s » De Re Militari". deremilitari.org. Retrieved 2017-11-11.

^ Pye, Michael (2015-04-15). The Edge of the World: A Cultural History of the North Sea and the Transformation of Europe. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781605987538.

^ Nicolle, David (2014-04-20). Forces of the Hanseatic League: 13th–15th Centuries. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781782007807.

^ Dutch independence was finally confirmed by the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648.

^ "Bremen (Germany)". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

^ "Bremen (Germany): Counties & Cities – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

^ [1]

^ Sir John Smythe Bolo Whistler: The Life of General Sir Lashmer Whistler Frederick Muller Ltd 1967

^ abc "Statistisches Jahrbuch 2016" (PDF). Statistisches Landesamt Bremen. Retrieved 2017-07-04.

^ 100 schräge Fakten über diese Stadt. In: Zitty 16/2012, p. 15.

^ "Wetterrekorde" (in German). Wetterdienst.de. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

^ -21,8 °Ré reports Heinrich Wilhelm Matthias Olbers in a letter to Carl Friedrich Gauss from 6 February 1823, printed in: Carl Friedrich Gauß, Briefwechsel mit H.W.M. Olbers, Georg Olms Verlag, 1860 S. 233 (Bremen, p. 233, at Google Books).

^ "Wetter und Klima im Überblick" (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst.

^ "Wetter und Klima im Überblick" (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst.

^ "Datenbankabfrage ausgewählter DWD Stationen Deutschlands" (in German). SKlima. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

^ "Wetter im Rückblick" (in German). wetteronline. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

^ [2]

^ [3]

^ "Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund I", (German). Retrieved 4 July 2017.

^ Buse, Dieter K. (2005-01-01). The Regions of Germany: A Reference Guide to History and Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32400-0.

^ "Bürgerschafts- und Beirätewahlen 2015, Vorläufiges Endergebnis" [2015 elections for Bürgerschaft and Beiräte (state, city, and local legislature), preliminary results] (in German). Statistisches Landesamt Bremen (Statistical Office of the State of Bremen). Retrieved 18 May 2015.

^ "Bürgerschaftswahl am 10. Mai 2015 in Bremen".

^ "Böttcherstraße: Welcome". Böttcherstraße GmbH. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

^ "St. Martin's Church". Bremen-tourism.de. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

^ "Birgittenkloster" (in German). Katholischer Gemeindeverband in Bremen. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

^ "Schlachte Embankment". bremen-tourism.de. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

^ "Das Viertel" (in German). dasviertel.de. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

^ "Nasir Moschee in Stuhr-Brinkum". Retrieved June 10, 2014.

^ Focke Museum

^ "Weserburg: Weserburg". weserburg.de.

^ Wolfgang Feist (2007-05-27). "Passivhaus-Schulgebäude" [Passive house school building] (in German). Passive House Institute. Archived from the original on 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

^ "GDP per capita (current US$) – Data". worldbank.org.

^ "EADS in Germany". Eads.com.

[dead link]

^ "Airbus in Germany". Airbus.com. Archived from the original on 2010-01-16.

^ "Mercedes-Benz Bremen Plant". www.daimler.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2010.

^ "BSAG Public transportation in Bremen" (in German). bsag.de.

^ "Regio-S-Bahn in Bremen gestartet" [Regio-S-Bahn in Bremen started] (in German). Radio Bremen. 12 December 2010. Archived from the original on December 14, 2010.

^ "Message of Greeting". Imo2009.de. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

^ "Zahlen und Fakten zur Universität" (in German). University of Bremen. Archived from the original on 2011-10-20. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

^ Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (zmt)

^ MARUM

^ IFAM

^ MEVIS

^ abcdefghijkl "Referat 32 – Städtepartnerschaften / Internationale Beziehungen" (official website/publication) (in German). Andrea Frohmader, Internationale Beziehungen / stellvertr. Abteilungsleiterin Senatskanzlei, Rathaus, Bremen. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2015-10-21.

^ "Gdańsk Official Website: 'Miasta partnerskie'" (in Polish and English). Urząd Miejski w Gdańsku. 2009. Archived from the original on 2013-07-23. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

^ "Twin cities of Riga". Riga City Council. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

^ "Sister Cities Home Page". Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. eThekwini Online: The Official Site of the City of Durban

^ "Sister in progress". Times of India – Pune Times. 30 August 2001.

^ "Profile: Mrs. Vandana H. Chavan (Ex Mayor of Pune)". Pune Diary. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

^ "Pune, twin cities to get pollution lab". Times of India – Pune Times. 4 September 2001.

^ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 2 Dec 1996". parliament.uk. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

External links

- Official city website

- Official visitors information (various languages)

- Bremen City Panoramas – Panoramic Views and virtual Tours

- Official site of the city center

- Official site of the Schnoor quarter

- Official site of the shopping quarter Das Viertel

- Official site of the Weser promenade Schlachte

- Official site of the shopping avenue Sögestraße

- Official site of the shopping mall Lloyd Passage

- Official site of the shopping quarter Ansgari Quartier

- Remnant from World War II in Bremen