Battle of Pusan Perimeter

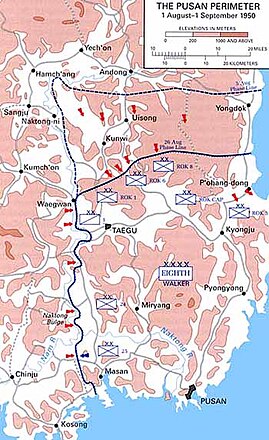

The Battle of Pusan Perimeter was a large-scale battle between United Nations and North Korean forces lasting from August 4 to September 18, 1950. It was one of the first major engagements of the Korean War. An army of 140,000 UN troops, having been pushed to the brink of defeat, were rallied to make a final stand against the invading North Korean army, 98,000 men strong.

UN forces, having been repeatedly defeated by the advancing North Koreans, were forced back to the "Pusan Perimeter", a 140-mile (230 km) defensive line around an area on the southeastern tip of the Korean Peninsula that included the port of Pusan. The UN troops, consisting mostly of forces from the Republic of Korea (ROK), United States and United Kingdom mounted a last stand around the perimeter, fighting off repeated North Korean attacks for six weeks as they were engaged around the cities of Taegu, Masan, and P'ohang, and the Naktong River. The massive North Korean assaults were unsuccessful in forcing the United Nations troops back further from the perimeter, despite two major pushes in August and September.

North Korean troops, hampered by supply shortages and massive losses, continually staged attacks on UN forces in an attempt to penetrate the perimeter and collapse the line. However, the UN used the port to amass an overwhelming advantage in troops, equipment, and logistics, and its navy and air forces remained unchallenged by the North Koreans during the fight. After six weeks, the North Korean force collapsed and retreated in defeat after the UN force launched a counterattack at Inchon on September 15. The battle would be the furthest the North Korean troops would advance in the war, as subsequent fighting ground the war into a stalemate.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Outbreak of war

2 Prelude

2.1 Forces involved

2.2 Logistics

2.2.1 UN logistics

2.2.2 North Korean logistics

2.3 Terrain

3 August push

3.1 Defensive position

3.2 UN Counteroffensive

3.3 Naktong Bulge

3.3.1 North Korean crossing

3.3.2 North Korean defeat

3.4 Eastern corridor

3.4.1 Triple offensive

3.4.2 Fight for P'ohang-dong

3.5 Taegu

3.5.1 Taegu advance

3.5.2 Triangulation Hill

3.5.3 Yongp'o

3.5.4 Carpet bombing

4 September push

5 Aftermath

5.1 Casualties

5.2 War crimes

5.3 Implications

6 References

6.1 Citations

6.2 Sources

Background

A map showing successive North Korean advance. The Pusan Perimeter is the border of the green portion of the peninsula.

Outbreak of war

Following the outbreak of the Korean War, the United Nations decided to commit troops in support of the Republic of Korea (South Korea), which had been invaded by the neighboring Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea). The United States subsequently sent ground forces to the Korean peninsula with the goal of fighting back the North Korean invasion and to prevent South Korea from collapsing. However, US forces in the Far East had been steadily decreasing since the end of World War II, five years earlier, and at the time the closest forces were the 24th Infantry Division of the Eighth United States Army, which was headquartered in Japan. The division was understrength, and most of its equipment was antiquated due to reductions in military spending. Regardless, the 24th Infantry Division was ordered into South Korea.[6]

The Korean People's Army (KPA), 89,000 men strong, had advanced into South Korea in six columns, catching the Republic of Korea Army (ROKA) by surprise and completely routing it. The smaller ROKA suffered from widespread lack of organization and equipment, and was unprepared for war.[7] Numerically superior, KPA forces destroyed isolated resistance from the 38,000 ROKA soldiers on the front before moving steadily south.[8] Most of South Korea's forces retreated in the face of the advance. By June 28, the KPA had captured South Korea's capital of Seoul, forcing the government and its shattered forces to retreat further south.[9] Though it was steadily pushed back, South Korean forces increased their resistance further south, hoping to delay KPA units as much as possible. North and South Korean units sparred for control of several cities, inflicting heavy casualties on one another. The ROKA defended Yongdok fiercely before being forced back, and managed to repel North Korean forces in the Battle of Andong.[10]

Outnumbered and under-equipped US forces—committed in piecemeal fashion as rapidly as they could be deployed—were repeatedly defeated and pushed south. The 24th Division, the first US division committed, took heavy losses in the Battle of Taejon in mid-July, which they were driven from after heavy fighting. Elements of the 3rd Battalion, 29th Infantry Regiment, newly arrived in the country, were wiped out at Hadong in a coordinated ambush by KPA forces on July 27, leaving open a pass to the Pusan area.[11][12] Soon after, Chinju to the west was taken, pushing back the 19th Infantry Regiment and leaving open routes to Pusan.[13] US units were subsequently able to defeat and push back the KPA on the flank in the Battle of the Notch on August 2. Suffering mounting losses, the KPA force on the west flank withdrew for several days to re-equip and receive reinforcements. This granted both sides several days of reprieve to prepare for the attack on the Pusan Perimeter.[14][15]

Prelude

Forces involved

The KPA forces were organized into a mechanized combined arms force of ten divisions, originally numbering some 90,000 well-trained and well-equipped troops in July, with hundreds of T-34 tanks.[16] However, defensive actions by US and South Korean forces had delayed the North Koreans significantly in their invasion of South Korea, costing them 58,000 of their troops and a large number of tanks.[17] In order to recoup these losses, the North Koreans had to rely on less-experienced replacements and conscripts, many of whom had been taken from the conquered regions of South Korea.[18] During the course of the battle, the North Koreans raised a total of 13 infantry divisions and one armored division to the fight at Pusan Perimeter.[17]

The UN forces were organized under the command of the United States Army. The Eighth United States Army served as the headquarters component for the UN forces, and was headquartered at Taegu.[19][20] Under it were three weak US divisions; the 24th Infantry Division was brought to the country early in July, while the 1st Cavalry Division and 25th Infantry Division arrived between July 14 and 18.[21] These forces occupied the western segment of the perimeter, along the Naktong River.[17] The ROKA, a force of 58,000,[22] was organized into two corps and five divisions; from east to west, ROK I Corps controlled the 8th Infantry Division and Capital Divisions, while the ROK II Corps controlled the 1st Division and 6th Infantry Division. A reconstituted ROK 3rd Division was placed under direct ROKA control.[23][24] Morale among the UN units was low due to the large number of defeats incurred to that point in the war.[25][19] US forces had suffered over 6,000 casualties over the past month, while the ROKA had lost an estimated 70,000.[1][26]

Troop numbers for each side have been difficult to estimate. The KPA had around 70,000 combat troops committed to the Pusan Perimeter on August 5, with most of its divisions far understrength.[1][27] It likely had less than 3,000 personnel in mechanized units, and around 40 T-34 tanks at the front, due to extensive losses so far in the war.[1][28]General Douglas MacArthur reported 141,808 UN troops in Korea on August 4, of which 47,000 were in US ground combat units and 45,000 in South Korean combat units. Thus the UN ground combat force outnumbered the North Koreans 92,000 to 70,000.[1][28] UN forces had complete control of the air and sea throughout the fight as well, and US Air Force and US Navy elements provided support for the ground units throughout the battle virtually unopposed.[29]

Overall command of the naval force was taken by the US Seventh Fleet, and the bulk of the naval power provided was also from the US.[30] The United Kingdom also provided a small naval task force including an aircraft carrier and several cruisers. Eventually, Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, and New Zealand provided ships as well.[31] Several hundred fighter-bombers of the Fifth Air Force were positioned within the perimeter and in Japan, and just off the coast were US Navy aircraft aboard the USS Valley Forge and the USS Philippine Sea. By the end of the battle the Eighth Army had more air support than General Omar Bradley's Twelfth United States Army Group in Europe during World War II.[32]

From south to northeast, the KPA units positioned opposite the UN units were the 83rd Motorized Regiment of the 105th Armored Division and then the 6th,[23] 4th, 3rd, 2nd, 15th,[21]1st, 13th, 8th, 12th, and 5th Divisions and the 766th Independent Infantry Regiment.[25]

Throughout September 1950, as the battle raged, more UN forces arrived from the US and other locations.[33] The 2nd Infantry Division, 5th Regimental Combat Team,[34]1st Provisional Marine Brigade and British 27th Commonwealth Brigade arrived in Pusan later in the fighting, along with large numbers of fresh troops and equipment, including over 500 tanks.[17][35] By the end of the battle, Eighth Army's force had gone from three under-strength, under-prepared divisions to four formations that were well equipped and ready for war.[36]

UN troops unload in Korea

An M4 Sherman tank being loaded into a barge at the port of Oakland, California, prior to shipment to Pusan, 1950.

Logistics

UN logistics

On July 1, the US Far East Command directed the Eighth United States Army to assume responsibility for all logistical support of the United States and UN forces in Korea.[37] including the ROKA.[38] Support for the American and South Korean armies came through the United States and Japan.[38] The re-equipping of the ROKA presented the UN forces with major logistical problems in July.[39] The biggest challenge was a shortage of ammunition. Though logistics situations improved over time, ammunition was short for much of the war.[40] Consumption of supplies differed among the various units and a lack of a previously drafted plan forced UN logisticians to create a system on the fly.[41]

The majority of resupply by sea was conducted by cargo ships of the US Army and US Navy.[42] The massive demand for ships forced the UN to charter private ships and bring ships out of the reserve fleet to increase the number of the military vessels in service.[43] Pusan was the only port in South Korea that had dock facilities large enough to handle a sizable amount of cargo.[44] An emergency airlift of critically needed items began almost immediately from the United States to Japan. Although it did not fly into Korea, the Military Air Transport Service (MATS), Pacific Division, expanded rapidly after the outbreak of the war.[45] The consumption of aviation gasoline thanks to both combat and transport aircraft was so great in the early phase of the war, taxing the very limited supply available in the Far East, that it became one of the serious logistical problems.[34] From Pusan a good railroad system built by the Japanese extended northward.[46] The railroads were the backbone of the UN transportation system in Korea.[44][47] The 20,000 mi (32,000 km) of Korean vehicular roads were all of a secondary nature, as measured by American or European standards.[34][48]

North Korean logistics

The North Koreans relied on a logistical system which was very lean and substantially smaller than the United Nations' system. This logistics network was therefore capable of moving far fewer supplies, and this caused considerable difficulty for front-line troops. Based on the efficient Soviet Army model, this ground-based network relied primarily on railroads to transport supplies to the front while troops transported those items to the individual units on foot, trucks, or carts. This second effort, though more versatile, was also a substantial disadvantage because it was less efficient and often too slow to follow the moving front-line units.[49]

US aircraft attack a North Korean train with rockets and napalm, 1950.

North Korea's lack of large airstrips and aircraft meant it conducted only minimal air resupply, mostly critical items being imported from China. Other than this, however, aircraft played almost no role in North Korean logistics.[50] The North Koreans were also unable to effectively use sea transport. Ports in Wonsan and Hungnam could be used for the transport of some troops and supplies, but they remained far too underdeveloped to support any large-scale logistical movements, and the port of Inchon in the south was difficult to navigate with large numbers of ships.[51][52]

In mid-July, the UN Far East Air Force Bomber Command began a steady and increasing campaign against strategic North Korean logistics targets. The first of these targets was Wonsan on the east coast. Wonsan was important as a communications center that linked Vladivostok, Siberia, with North Korea by rail and sea. From it, rail lines ran to all the North Korean build-up centers. The great bulk of Russian supplies for North Korea in the early part of the war came in at Wonsan, and from the beginning it was considered a major military target.[53] By July 27, the FEAF Bomber Command had a comprehensive rail interdiction plan ready.[54] This plan sought to cut the flow of North Korean troops and materiel from North Korea to the combat area. Two cut points, the P'yong-yang railroad bridge and marshaling yards and the Hamhung bridge and Hamhung and Wonsan marshaling yards, would almost completely sever North Korea's rail logistics network. Destruction of the rail bridges over the Han River near Seoul would cut rail communication to the Pusan Perimeter area.[34] On August 4, FEAF began B-29 interdiction attacks against all key bridges north of the 37th Parallel in Korea and, on August 15, light bombers and fighter-bombers joined in the interdiction campaign.[55]

The supremacy of the Fifth Air Force in the skies over Korea forced the North Koreans in the first month of the war to resort to night movement of supplies to the battle area.[52] They relied primarily on railroads to move supplies to the front, however a shortage of trucks posed the most serious problem of getting supplies from the trains to individual units, forcing them to rely on carts and pack animals.[49] The KPA was able to maintain transport to its front lines over long lines of communications despite heavy and constant air attacks. The UN air effort failed to completely halt military rail transport.[56] Ammunition and motor fuel, which took precedence over all other types of supply, continued to arrive at the front, though in smaller amounts than before.[57] At best there were rations for only one or two meals a day.[58] Most units had to live at least partially off the South Korean populace, scavenging for food and supplies at night.[59] By September 1 the food situation was so bad in the KPA at the front that most of the soldiers showed a loss of stamina with resulting impaired combat effectiveness.[56]

The inefficiency of its logistics remained a fatal weakness of the KPA, costing it crucial defeats after an initial success with combat forces.[49] The North Koreans' communications and supply were not capable of exploiting a breakthrough and of supporting a continuing attack in the face of massive air, armor, and artillery fire that could be concentrated against its troops at critical points.[60]

Terrain

The main Seoul-Pusan railway and road was integral in bringing supplies to the front

The UN forces established a perimeter around the port city of Pusan throughout July and August 1950. Roughly 140 miles (230 km) long, the perimeter stretched from the Korea Strait to the Sea of Japan west and north of Pusan.[16] To the west the perimeter was roughly outlined by the Naktong River where it curved at the city of Taegu, except for the southernmost 15 miles (24 km) where the Naktong turned eastward after its confluence with the Nam River.[61] The northern boundary was an irregular line that ran through the mountains from above Waegwan and Andong to Yongdok.[16]

With the exception of the Naktong delta to the south, and the valley between Taegu and P'ohang-dong, the terrain is extremely rough and mountainous. Northeast of P'ohang-dong along the South Korean line the terrain was especially treacherous, and movement in the region was extremely difficult. Thus, the UN established the Pusan Perimeter in a location outlined by the Sea of Japan to the south and east, the Naktong River to the west, and extremely mountainous terrain to the north, using the terrain as a natural defense.[23] However the rough terrain also made communication difficult, particularly for the South Korean forces in the P'ohang-dong area.[25]

Forces in this region also suffered from casualties related to the heat of the summer, as the Naktong region has little vegetation and clean water.[26] Korea suffered from a severe drought in the summer of 1950, receiving only 5 in (130 mm) of rain as opposed to the normal 20 in (510 mm) during the months of July and August. Combined with temperatures of 105 °F (41 °C), the hot and dry weather contributed to a large number of heat and exertion casualties, particularly for the unconditioned American forces.[62]

August push

Map of the Pusan Perimeter, August 1950.

Defensive position

Saddle Ridge near Taegu, one of the positions along Pusan Perimeter defended by the UN.

On August 1, the US Eighth Army issued an operational directive to all UN ground forces in Korea for their planned withdrawal east of the Naktong River.[63] UN units would then establish main defensive positions behind what was to be called the Pusan Perimeter. The intent was to draw the line on retreating and hold off the KPA while the UN built up its forces and launched a counteroffensive.[64] The US 25th Infantry Division held the southernmost flank at Masan,[64] while the 24th Infantry Division withdrew to Koch'ang.[65] The 1st Cavalry Division withdrew to Waegwan.[66] US forces demolished all bridges over the Naktong River in the retreat.[63] At one bridge in the 1st Cavalry Division sector, the division commander attempted several times to clear refugees from the bridge but they continued to cross it despite warnings and several attempts to clear the bridge. Eventually the commander was forced to demolish the bridge, taking several hundred refugees with it.[66]

Central to the UN defensive plan was to hold the port of Pusan, where vital ground supplies and reinforcements were arriving from Japan and the US.[19] Pusan possessed airfields where US combat and cargo aircraft were streaming into Korea with more supplies.[67] A system similar to the Red Ball Express in World War II was employed to get supplies from Pusan to the front lines.[68] Hundreds of ships arrived in Pusan each month, starting with 230 in July and increasing steadily thereafter.[36] On July 24, the UN established its highest command under MacArthur in Tokyo, Japan.[69] North Korean forces in the meantime were suffering from overextended supply lines which severely reduced their fighting capacity.[70]

North Korean forces had four possible routes in the perimeter: to the south, the pass through the city of Masan around the confluence of the Nam and Naktong rivers; another southerly route through the Naktong Bulge and into the railroad lines at Miryang; through the route into Taegu in the north; and through Kyongju in the eastern corridor.[71] North Korea mounted a large offensive in August, simultaneously attacking all four entries into the perimeter.[72] As a result, the Battle of Pusan Perimeter was not one single engagement but a series of large battles fought between the UN and North Korean divisions all along the perimeter.[73]

UN Counteroffensive

Troops of the 24th Infantry move to the Masan battleground

The Eighth Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Walton Walker, began preparing a counteroffensive, the first conducted by the UN in the war, for August. It would kick off with an attack by the US reserve units on the Masan area to secure Chinju, followed by a larger general push to the Kum River in the middle of the month.[74][75] One of Walker's goals was to break up a suspected massing of North Korean troops near the Taegu area by forcing the diversion of some North Korean units southward. On August 6, the Eighth Army issued the operational directive for the attack by Task Force Kean, named for the US 25th Infantry Division commander, William B. Kean. Task Force Kean consisted of the 25th Division, less the 27th Infantry Regiment and a field artillery battalion, plus the 5th Regimental Combat Team and the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade attached — a force of about 20,000 men.[76] The plan of attack required the force to move west from positions held near Masan, seize the Chinju Pass, and secure the line as far as the Nam River.[77] However, the offensive relied on the arrival of the entire 2nd Infantry Division, as well as three more battalions of American tanks.[62]

Task Force Kean launched its attack on August 7, moving out from Masan,[78] but Kean's offensive had collided in a meeting engagement with one being simultaneously delivered by the North Koreans.[79][80] Heavy fighting continued in the area for three days. By August 9, Task Force Kean was poised to retake Chinju.[81] The Americans initially advanced quickly though North Korean resistance was heavy.[82] On August 10, the Marines picked up the advance.[13] However, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was withdrawn from the force on August 12 to be redeployed elsewhere on the perimeter.[79][83] Task Force Kean continued forward, capturing the area around Chondong-ni.[84] Eighth Army requested several of its units to redeploy to Taegu to be used elsewhere on the front, particularly at the Naktong Bulge.[14][83]

US Armor advances west of Masan

An attempt to move the 25th Infantry Division's division trains through the valley became mired in the mud through the night of August 10–11 and was attacked in the morning by KPA forces who had driven American forces from the high ground.[85] In the confusion, North Korean armor was able to penetrate roadblocks and assault the supporting US artillery positions.[86] The surprise attack was successful in wiping out most of the 555th and 90th Field Artillery battalions, with much of their equipment.[87] Both North Korean and American armor swarmed to the scene and US Marine aircraft continued to provide cover, but neither side was able to make appreciable gains despite inflicting massive numbers of casualties on one another.[88] Upon later inspection, the bodies of 75 men, 55 from the 555th Field Artillery and 20 from the 90th Field Artillery, were found executed when the area again came under American control.[89] Task Force Kean was forced to withdraw back to Masan, unable to hold its gains, and by August 14 it was in approximately the same position it had been in when it started the offensive.[90]

Task Force Kean had failed in its objective of diverting North Korean troops from the north, and also failed in its objective of reaching the Chinju Pass. However, the offensive was considered to have significantly increased morale among the troops of the 25th Infantry Division, which performed extremely well in subsequent engagements.[91][92] The KPA 6th Division had been reduced to 3,000-4,000 and had to replenish its ranks with South Korean conscripts from Andong.[93] Fighting in the region continued for the rest of the month.[94]

Naktong Bulge

About 7 miles (11 km) north of the confluence of the Naktong and Nam Rivers, the Naktong curves westward opposite Yongsan in a wide semicircular loop. For most of this span, the Naktong river is around 1,300 feet (400 m) wide and 6 feet (1.8 m) deep, allowing infantry to wade across with some difficulty, but preventing vehicles from crossing without assistance.[95] This perimeter was manned by a network of observation posts on the high ground where forces from the 24th Infantry Division monitored the river area.[58] Forces in reserve would counterattack any attempted crossings by North Korean forces.[96] The division was spread extremely thinly; already understrength, it presented a very weak line.[71][97]

US Marines sit on a newly captured position overlooking the Naktong River, August 19

North Korean crossing

US Navy Corpsman treats US Marine casualty from the front line of the battle, August 17.

On the night of August 5–6, 800 North Korean soldiers began wading across the river at the Ohang ferry site, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) south of Pugong-ni and west of Yongsan, carrying light weapons and supplies over their heads or on rafts.[98][99] A second force attempted to cross the river further north but met with resistance and fell back. On the morning of August 6, the North Koreans attacked in an attempt to penetrate the lines to Yongsan.[98] This caught the Americans, who were expecting an attack from further north, by surprise and drove them back.[100] Subsequently, the North Koreans were able to capture a large amount of American equipment.[14] The attack threatened to split the American lines and disrupt supply lines to the north.[101]

Despite American counterattacks, the North Koreans were able to continue pressing forward and take Cloverleaf Hill and Oblong-ni Ridge, critical terrain astride the main road in the bulge area.[100][101] By August 10 the entire KPA 4th Division was across the river and beginning to move south, outflanking the American lines. The next day, scattered elements of the North Korean forces attacked Yongsan.[101][102] The KPA forces repeatedly attacked US lines at night, when American soldiers were resting and had greater difficulty resisting.[103]

North Korean defeat

The 1st Marine Provisional Brigade, in conjunction with Task Force Hill, mounted a massive offensive on Cloverleaf Hill and Obong-ni on August 17.[104] At first tenacious North Korean defense halted the Marines' push. The North Koreans then mounted a counterattack following this in hopes of pushing the Marines back, but this failed disastrously.[103][105][106] By nightfall on August 18, the KPA 4th Division had been nearly annihilated and Obong-ni and Cloverleaf Hill had been retaken by US forces.[105] The next day, the remains of the 4th Division withdrew completely across the river.[107][108] In their hasty retreat, they left a large number of artillery pieces and equipment behind which the Americans used.[109]

Eastern corridor

The terrain along the South Korean front on the eastern corridor made movement extremely difficult. A major road ran from Taegu 50 miles (80 km) east, to P'ohang-dong on Korea's east coast.[110] The only major north-south road intersecting this line moved south from Andong through Yongch'on, midway between Taegu and P'ohang-dong. The only other natural entry through the line was at the town of An'gang-ni, 12 miles (19 km) west of P'ohang-dong, situated near a valley through the natural rugged terrain to the major rail hub of Kyongju, which was a staging post for moving supplies to Taegu.[110] Walker chose not to heavily reinforce the area as he felt the terrain made meaningful attack impossible, preferring to respond to attack with reinforcements from the transportation routes and air cover from Yongil Airfield, which was south of P'ohang-dong.[111]

South Korean units push North Korean forces northward after intense fighting, August 11–20.

Triple offensive

In early August, three North Korean divisions mounted offensives against the three passes through the area, with the 8th Division attacking Yongch'on, 12th Division attacking P'ohang-dong and 5th Division, in conjunction with the 766th Independent Infantry Regiment, attacking An'gang-ni.[112] The 8th Division drove for Yongch'on from Uiseong, but its attack failed to reach the Taegu-P'ohang corridor after being surprised and outflanked by the ROKA 8th Division. This fighting was so heavy that the KPA 8th Division was forced to hold its ground for a week before trying to advance. Stalled again by South Korean resistance, it halted to wait for reinforcements.[112] However the other two attacks were more successful, catching the UN forces by surprise.[110]

East of the KPA and ROK 8th Divisions, the KPA 12th Division crossed the Naktong River at Andong, moving through the mountains in small groups to reach P'ohang-dong.[108] UN planners had not anticipated that the 12th Division would be able to cross the river effectively, and thus were unprepared.[113] In the meantime, the ROKA 3rd Division was heavily engaged with the KPA 5th Division along the coastal road to P'ohang-dong. The divisions' clashes centered on the town of Yongdok, with each side capturing and recapturing the town several times. On August 5, the North Koreans attacked, again taking the town from the South Korean forces and pushing them south. On August 6, the South Koreans launched a counteroffensive to retake the town. However, KPA 5th Division forces were able to infiltrate the coastal road south of Yongdok at Hunghae. This effectively surrounded the ROKA 3rd Division, trapping it several miles above P'ohang-dong.[114] The KPA 766th Independent Regiment advanced around the ROK 3rd Division and took the area around P'ohang-dong.[115]

Marines carrying a wounded comrade in a stretcher in August 1950.

On August 10, the Eighth Army organized Task Force P'ohang — the ROKA 17th, 25th, and 26th Regiments as well as the ROKA 1st Anti-Guerrilla Battalion, Marine Battalion and a battery from the US 18th Field Artillery Regiment. This task force was given the mission to clear out North Korean forces in the mountainous region.[116] At the same time, Eighth Army formed Task Force Bradley, consisting of elements of the 8th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division.[117] Task Force Bradley was tasked with defending P'ohang-dong.[115] What followed was a complicated series of fights throughout the region around P'ohang-dong and An'gang-ni as ROKA forces, aided by US air forces, engaged groups of North Korean forces in the area. The KPA 12th Division was operating in the valley west of P'ohang-dong and was able to push back Task Force P'ohang and the ROKA Capital Division, which was along the line to the east. At the same time, the KPA 766th Infantry Regiment and elements of the KPA 5th Division fought Task Force Bradley at and south of P'ohang-dong. US naval fire drove the KPA troops from the town, but it became a bitterly contested no man's land as fighting moved to the surrounding hills.[118]

ROK troops advance to the front lines near P'ohang-dong

Fight for P'ohang-dong

By August 13, North Korean troops were operating in the mountains west and southwest of Yongil Airfield. USAF commanders, wary of North Korean attacks, evacuated the US 39th Fighter Squadron and US 40th Fighter Squadron from the airstrip, against the wishes of General MacArthur. In the event, the airstrip remained under the protection of UN ground forces and never came under direct fire.[119] The squadrons were moved to Tsuiki Air Field on the island of Kyushu, Japan.[57] In the meantime, the ROKA 3rd Division, surrounded earlier in the month, was forced further south to the village of Changsa-dong, where US Navy craft amphibiously withdrew the division. The division would sail 20 miles (32 km) south to Yongil Bay to join the other UN forces in a coordinated attack to push the North Koreans out of the region.[57][120] This evacuation was carried out on the night of August 16.[108]

By August 14, large KPA forces were focused entirely on taking P'ohang-dong. However they were unable to hold it because of US air superiority and naval bombardment on the town.[120] The North Korean supply chain had completely broken down and more food, ammunition, and supplies were not available. UN forces began their final counteroffensive against the stalled North Korean forces on August 15. Intense fighting around P'ohang-dong ensued for several days as each side suffered large numbers of casualties in back-and-forth battles.[121] By August 17, UN forces were able to push KPA troops out of the Kyongju and An'gang-ni areas, putting the supply road to Taegu out of immediate danger.[122] By August 19 the North Korean forces had completely withdrawn from the offensive.[57]

Taegu

Shortly before the Pusan Perimeter battles began, Walker established Taegu as the Eighth Army's headquarters.[113] Right at the center of the Pusan Perimeter, Taegu stood at the entrance to the Naktong River valley, an area where North Korean forces could advance in large numbers in close support. The natural barriers provided by the Naktong River to the south and the mountainous terrain to the north converged around Taegu, which was also the major transportation hub and last major South Korean city aside from Pusan itself to remain in UN hands.[123] From south to north, the city was defended by the US 1st Cavalry Division, and the ROK 1st and 6th Divisions of ROK II Corps. 1st Cavalry Division was spread out along a long line along the Naktong River to the south, with its 5th and 8th Cavalry Regiment holding a line 24 kilometres (15 mi) along the river and the 7th Cavalry Regiment in reserve along with artillery forces, ready to reinforce anywhere a crossing could be attempted.[124]

Taegu advance

Five North Korean divisions amassed to oppose the UN at Taegu; from south to north, the 10th,[23] 3rd, 15th, 13th,[21] and 1st Divisions occupied a line from Tuksong-dong and around Waegwan to Kunwi.[125] The North Koreans planned to use the natural corridor of the Naktong valley from Sangju to Taegu as their main axis of attack for the next push south.[126] Elements of the 105th Armored Division were also supporting the attack.[124][127]

By August 7, the KPA 13th Division had crossed the Naktong River at Naktong-ni, 40 miles (64 km) northwest of Taegu.[124] ROKA troops attacked the 13th Division immediately after it completed its crossing, forcing the North Korean troops to scatter into the mountains. The division reassembled to the east and launched a concerted night attack, broke the ROKA defenses, and began an advance that carried it twenty miles (32 km) southeast of Naktong-ni on the main road to Taegu. Within a week, the KPA 1st and 13th divisions were converging on the Tabu-dong area, about 15 miles (24 km) north of Taegu.[128]

US artillery near Waegwan fires at North Korean troops attempting to cross the Naktong River

During August 12–16, the KPA 15th Division formed up on the east side of the Naktong River in the vicinity of Yuhak-san, 3 miles (4.8 km) northwest of Tabu-dong. It was quickly locked in combat on Yuhak-san with the ROKA 1st Division.[129][130]

Triangulation Hill

South of Waegwan, two more North Korean divisions stood ready to cross the Naktong River in a coordinated attack with the divisions to the north.[129] The experienced KPA 3rd Division was concentrated in the vicinity of Songju, while the untested KPA 10th Division was concentrated in the Koryong area.[131] These two divisions crossed in the US 1st Cavalry Division's line. The KPA 3rd Division's 7th Regiment started crossing the Naktong on August 9. Despite being spotted and taking fire, the bulk of it reached the east bank safely and moved inland into the hills.[129] The 5th Cavalry Regiment and its supporting artillery, now fully alerted, spotted the other two regiments and forced them back to the west bank.[131] Only a small number of North Koreans reached the east side where either they were captured, or hid until recrossing the river the following night.[129]

At dawn on August 9, 1st Cavalry Division learned of the North Korean crossing.[132] North Korean infantry had gathered on Hill 268, also known as Triangulation Hill, which was 3 miles (4.8 km) southeast of Waegwan and 10 miles (16 km) northwest of Taegu.[133] The hill was important for its proximity to lines of communication, as the main Korean north-south highway and the main double-track Seoul-Pusan railroad skirted its base.[132] 1st Cavalry Division counterattacked the North Koreans gathering to force them back across the river, but their initial assault was repelled. The next morning, August 10, air strikes and artillery barrages rocked Hill 268, devastating the North Koreans, who withdrew back behind the river.[133]

Yongp'o

The North Korean plan for the attack against Taegu from the west and southwest demanded the KPA 3rd and 10th Divisions make a coordinated attack. [134] Elements of the 10th Division began crossing the Naktong early on August 12, in the vicinity of Tuksong-dong, on the Koryong-Taegu road, but were driven back.[135] A more determined North Korean crossing began early in the morning on August 14.[135] This attack also stalled and was driven back to the river.[130] By nightfall, the bridgehead at Yongp'o was eliminated.[136]

Carpet bombing

US Air Force post-strike picture of a 3.5-by-7.5-mile (5.6 by 12.1 km) area near Waegwan, in which 99 bombers dropped 3500, 500lb bombs

In the mountains northeast of Waegwan, the ROKA 1st Division continued to suffer North Korean attacks throughout mid-August. North Korean pressure against the division never ceased for long. US planners believed the main North Korean attack would come from the west, and so it massed its forces to the west of Taegu. It mistakenly believed up to 40,000 North Korean troops were near Taegu. This number was above the actual troop numbers for North Korea, which had only 70,000 men along the entire perimeter.[135]

On August 14, General MacArthur ordered the carpet bombing of a 27-square-mile (70 km2) rectangular area on the west side of the Naktong River opposite the ROKA 1st Division.[135] On August 16, bombers dropped approximately 960 tons of bombs on the area.[137][138] The attack required the entire FEAF bombing component, and comprised the largest Air Force operation since the Battle of Normandy in World War II.[139]

Information obtained later from North Korean prisoners revealed the divisions the Far East Command thought to be still west of the Naktong had already crossed to the east side and were not in the bombed area.[140] No evidence was found that the bombing killed a single North Korean soldier.[139] However, the bombing appeared to have destroyed a significant number of North Korean artillery batteries, as artillery fire on UN positions waned substantially following the mission.[140] The UN ground and air commanders opposed future massive carpet bombing attacks against enemy tactical troops unless there was precise information on an enemy concentration and the situation was critical.[140] Instead, they recommended fighter-bombers and dive bombers would better support ground forces.[139]

September push

Map of the Naktong Defensive line, September 1950.

The KPA had been pushed to its limits and many of the original units were at much reduced strength and effectiveness by the end of August.[56][141] Logistical problems wracked the North Koreans, with shortages of food, weapons, equipment and replacement soldiers common.[142][143] By late August, the UN command had more combat soldiers in Korea than the North Koreans, and the UN had near-total superiority over the air and sea.[56] North Korean tank losses had been in the hundreds, and it had fewer than 100 tanks by September 1, compared to the Americans' 600 tanks. By the end of August the North Koreans' only remaining advantage was their initiative, as the North Korean troops retained a high morale and enough supplies to allow for a large-scale offensive.[144]

Fed by intelligence from the Soviet Union, the North Koreans were aware the UN forces were building up along the Pusan Perimeter and that they had to conduct an offensive soon or else forfeit the battle.[145] In planning its new offensive, the North Korean commanders decided that any attempt to flank the UN force was impossible thanks to the support of the UN navy.[127] Instead, they opted to use frontal attacks to breach the perimeter and collapse it.[56] A secondary objective was to surround Taegu and destroy the UN and ROKA units in that city. As part of this mission, the North Korean units would first cut the supply lines to Taegu.[141]

North Korean planners enlarged their force in anticipation of a new offensive.[146] The army, originally numbering 10 divisions in two corps, was enlarged to 14 divisions with several independent brigades.[147] The new troops were brought in from reserve forces based in North Korea.[148]Marshal Choe Yong Gun served as deputy commander of the KPA, with General Kim Chaek in charge of the Front Headquarters.[145] Beneath them were the II Corps in the east, and I Corps in the west. II Corps controlled the KPA 10th, 2nd, 4th, 9th, 7th, and 6th Divisions as well as the 105th Armored Division, with the 16th Armored Brigade and 104th Security Brigade in support. I Corps commanded the 3rd, 13th, 1st, 8th, 15th, 12th, and 5th Divisions with the 17th Armored Brigade in support.[147] This force numbered approximately 97,850 men, although a third of it comprised raw recruits or forced conscripts from South Korea, and lacked weapons and equipment.[2][149] By August 31 they were facing a UN force of 120,000 combat troops plus 60,000 support troops.[150]

On August 20, the North Korean commands distributed operations orders to their subordinate units.[145] These orders called for a simultaneous five-prong attack against the UN lines. This would overwhelm the UN defenders and allow the North Koreans to break through the lines in at least one place to push the UN forces back. Five battle groupings were ordered as follows:[2]

- 6th and 7th Divisions to break through the US 25th Infantry Division at Masan.

- 9th, 4th, 2nd, and 10th Divisions to break through the US 2nd Infantry Division at the Naktong Bulge to Miryang and Yongsan.

- 3rd, 13th, and 1st Divisions to break through the US 1st Cavalry Division and ROK 1st Division to Taegu.

- 8th and 15th Divisions to break through the ROKA 8th Division and ROKA 6th Division to Hayang and Yongch'on.[151]

- 12th and 5th Divisions to break through the ROKA Capital Division and ROKA 3rd Division to P'ohang-dong and Kyongju.

On August 22, North Korean Premier Kim Il Sung ordered the war to be over by September 1, but the scale of the offensive did not allow for this.[148] Groups 1 and 2 were to begin their attack at 23:30 on August 31, and Groups 3, 4, and 5 would begin their attacks at 18:00 on September 2.[151] The attacks were to closely connect in order to overwhelm UN troops at each point simultaneously, forcing breakthroughs in multiple places that the UN would be unable to reinforce.[145][150] The North Koreans also relied primarily on night attacks to counter the UN's major advantages in air superiority and naval firepower. North Korean generals thought such night attacks would prevent UN forces from firing effectively and result in large numbers of UN friendly fire casualties.[152]

The attacks caught UN planners and troops by surprise.[153] By August 26, the UN troops believed they had destroyed the last serious threats to the perimeter, and anticipated the war ending by late November.[154] ROKA units, in the meantime, suffered from low morale thanks to their failures to defend effectively thus far in the conflict.[155] UN troops were looking ahead to Operation Chromite, their amphibious assault far behind North Korean lines at the port of Inchon on September 15, and did not anticipate the North Koreans would mount a serious offensive before then.[156]

The Great Naktong Offensive was one of the most brutal fights of the Korean War.[157] The five-prong offensive led to heavy fighting around Haman, Kyongju, Naktong Bulge, Nam River, Yongsan, Tabu-Dong and Ka-san.[158][159] The North Korean attacks made appreciable gains and forced the UN troops along the Pusan Perimeter to form a thin line of defense, relying on mobile reserves for the strength to push back North Korean attackers. From September 1 – 8 this fighting was intense and the battle was a very costly deadlock for the two overextended armies.[160] The North Koreans were initially successful in breaking through UN lines in multiple places and made substantial gains in surrounding and pushing back UN units.[145] On September 4–5 the situation was so dire for the UN troops that the US Eighth Army and ROKA moved their headquarters elements from Taegu to Pusan to prevent them from being overrun, though Walker remained in Taegu with a small forward detachment. They also prepared their logistics systems for a retreat to a smaller defensive perimeter called the "Davidson Line." By September 6, however, Walker decided another retreat would not be necessary.[161]

On September 15, exhausted North Korean troops were caught unaware by the landings at Inchon, far behind their lines. Those forces that remained after 15 days of fighting were forced to retreat in a total rout or risk being completely cut off.[162] Isolated North Korean resistance continued until September 18, but on that date UN troops were mounting a full-scale breakout offensive and pursuing retreating North Korean units to the north, ending the fighting around the Pusan Perimeter.[163]

Aftermath

The Pusan Perimeter on September 15. The blue arrow indicated the Battle of Inchon, which had ended the attack on the perimeter.

Medals of Honor were awarded to 17 US servicemen in the fight. US Air Force Major Louis J. Sebille was the only person from his branch to receive the medal.[73] US Army recipients include Master Sergeant Melvin O. Handrich,[164] Private First Class Melvin L. Brown,[165] Corporal Gordon M. Craig,[166] Private First Class Joseph R. Ouellette,[167] Sergeant First Class Ernest R. Kouma,[168] Master Sergeant Travis E. Watkins, First Lieutenant Frederick F. Henry,[169] Private First Class Luther H. Story,[170] Sergeant First Class Charles W. Turner, Private First Class David M. Smith,[171] Sergeant First Class Loren R. Kaufman,[172] and Private First Class William Thompson.[173] Sergeant William R. Jecelin[174] and Corporal John W. Collier were also awarded the medal during the breakout offensive.[175] One Commonwealth servicemen was awarded the Victoria Cross during the breakout offensive, Major Kenneth Muir.[176]

Casualties

Both the UN and North Korean forces suffered massive casualties. The US 5th Regimental Combat Team had 269 killed, 574 wounded and four captured during the battle.[177] The US 1st Cavalry Division suffered 770 killed, 2,613 wounded and 62 captured.[178] The 2nd Infantry Division suffered 1,120 killed, 2,563 wounded, 67 captured and 69 missing.[172] The 24th Infantry Division suffered 402 killed, 1,086 wounded, five captured and 29 missing.[179] The 29th Infantry Regimental Combat Team suffered 86 killed, 341 wounded, 1 captured and 7 missing.[180] The 25th Infantry Division suffered 650 killed, 1,866 wounded, four captured and 10 missing.[181] With other non-divisional units, the US Army's total casualty count for the battle was 3,390 killed, 9,326 wounded, 97 captured (9 of whom died in captivity) and 174 missing, adding up to 12,987 casualties.[182] The US Marine Corps suffered 185 killed, the US Navy suffered 14 killed and the US Air Force suffered 53 killed.[171] Another 736 were killed, 2,919 wounded and 12 missing during the breakout offensive from the perimeter.[183] The official count for US casualties was 4,599 killed, 12,058 wounded, 2,701 missing, 401 captured.[142][4] North Korean casualty numbers are nearly impossible to estimate, but are known to be at least twice the total UN casualty count, or at least 40,000.[3] The US also lost 60 tanks in the fight, bringing the total number lost in the war to that date to 136.[184]

There were also a small number of British casualties in the campaign, including five soldiers killed. Naval rating J.W. Addison was the first casualty in Pusan, killed August 23 aboard HMS Comus when the ship was attacked by a North Korean aircraft.[185] On August 29, Lieutenant Commander I. M. MacLachlan, commander of 800 Naval Air Squadron, was killed in an aircraft accident aboard HMS Triumph.[186] Additionally, three British troops of the 27th Brigade were killed near Taegu; Private Reginald Streeter was killed September 4, and Captain C. N. A. Buchanan and Private T. Taylor died September 6. Another 17 British soldiers were wounded in the area.[187]

Two war correspondents were killed in the campaign, Ian Morrison, a reporter for The Times, and Christopher Buckley, a reporter for The Daily Telegraph, were killed August 13 near Waegwan when their vehicle struck a landmine. One Indian Armed Forces officer was also killed in the incident, Colonel Manakampat Kesavan Unni Nayar, a representative from the United Nations Commission on Korea.[188]

North Korean casualties for the battle are almost impossible to estimate precisely due to a lack of records. It is difficult to determine how many South Korean citizens were forcibly conscripted during the battle and how many deserted as opposed to being killed. Larger engagements destroyed entire regiments and even divisions of North Korean troops, and their strength had to be estimated based on accounts of North Koreans captured by the UN. On September 1, the KPA numbered approximately 97,850 in South Korea, and up to one third of this number is suspected to have been conscripts from South Korea.[2] In the aftermath of the Pusan Perimeter battle, only 25,000 or 30,000 of these soldiers returned to North Korea by the end of the month. Upwards of one third of the attacking force became casualties in the fighting. This would mean North Korean casualties from September 1 to 15 could range from roughly 41,000 to 36,000 killed and captured, with an unknown number of wounded.[189] With the addition of the 5,690 killed in the Bowling Alley, 3,500 at the Naktong Bulge,[105] at least 3,700 at Taegu[135][190][191] and an unknown number at P'ohang-dong before September 1, North Korean casualties likely topped 50,000 to 60,000 by the end of the battle. They also lost 239 T-34 tanks and 74 SU-76 self-propelled guns; virtually all of the armor they possessed.[184]

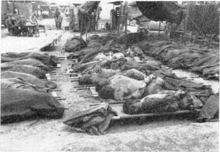

War crimes

Bodies of Hill 303 massacre victims gathered near Waegwan, South Korea, many with their hands still bound.

Instances of war crimes were alleged to have occurred on both sides of the conflict, and troops from both the UN and North Korea were involved in several high-profile incidents. The North Korean troops, in occupying South Korea, were accused of many instances of abuse of prisoners of war captured during the fighting. Most serious among these were accusations that some captured UN prisoners were tortured and executed. Isolated incidents of prisoners being beaten, castrated, burned to death,[192] and used for bayonet practice arose. In the Taegu region, groups of captured soldiers were found executed with their hands bound.[193] This was also known to have occurred at Masan,[89] where isolated instances of prisoners being used as human shields against other UN troops were known to have taken place.[194] Critically wounded UN troops were known to have been killed, and in at least one instance, unarmed chaplains and medics were attacked despite wearing proper identification.[195] The North Koreans were also known to have forcibly conscripted South Korean civilians into their armies on a large scale, killing any who attempted to desert.[196][197]

The most infamous war crime was the Hill 303 massacre on August 17, when 41 US prisoners of war were killed by North Koreans driving on Taegu. The crime led UN Commander Douglas MacArthur to warn the North Koreans via leaflets and broadcasts that they would be held responsible for such crimes.[57][198][199] Historians agree there is no evidence that the North Korean High Command sanctioned the shooting of prisoners during the early phase of the war.[57] The Hill 303 massacre and similar atrocities are believed to have been conducted by "uncontrolled small units, by vindictive individuals, or because of unfavorable and increasingly desperate situations confronting the captors."[198][200]T. R. Fehrenbach, a military historian, wrote in his analysis of the event that North Korean troops committing these acts were likely accustomed to torture and execution of prisoners due to decades of rule by oppressive armies of the Empire of Japan up until World War II.[138] North Korean commanders are known to have issued more stern orders regarding treatment of prisoners of war after these incidents, though such atrocities continued.[200]

UN troops, particularly South Korean, were also accused of killing or attempting to kill captured North Korean soldiers. South Korean civilians, some of whom were leftist or communist sympathizers, were known to have been systematically imprisoned or killed in the Bodo League massacres, some of which have taken place during the battle.[201][202] In the years since the fight, evidence has also surfaced indicating that the US military killed South Korean civilians shortly before the fight along the Pusan Perimeter began, fearing them North Korean infiltrators, in the No Gun Ri massacre. The evidence is debated but several books have been published on the matter.[203]

Implications

Some historians contend the goals of the North Koreans at the Pusan Perimeter were unattainable from the beginning.[204] According to historian T. R. Fehrenbach, the Americans, who had been better equipped than the North Koreans, were easily able to defeat their opponents once they had the chance to form a continuous line.[144] At the same time, the North Koreans did break through the perimeter at several points and were able to exploit their gains for a short time.[150] Within a week, though, the momentum of the offensive had been slowed and the North Koreans could not keep up the strength of their attacks.[162] Most of the front saw only probing actions for the remainder of the battle.[163]

North Korean T-34 tanks destroyed by US Air Force bombs near Waegwan.

The Inchon landings were a crushing blow for the KPA, catching it completely unprepared and breaking the already weak forces along the perimeter.[205] With virtually no equipment, exhausted manpower and low morale, the North Koreans were at a severe disadvantage and were not able to continue to pressure on the Pusan Perimeter while attempting to repel the landings at Inchon.[5] By September 23, the North Koreans were in full retreat from the Pusan Perimeter, with UN forces rapidly pursuing them north and recapturing lost ground along the way.[205]

The destruction of the KPA at Pusan made communist continuation of the war impossible with North Korean troops alone. The massive equipment and manpower losses rivaled those of the ROKA in the first stages of the war. The North Koreans totally collapsed as a fighting force, and the remainder of their routed military retreated into North Korea offering very weak resistance against the UN force, which was now on the offensive with overwhelming superiority by land, air and sea.[206] Many of the outmaneuvered North Korean units simply surrendered, having been reduced from units of thousands to just a few hundred men.[189]

With the successful Pusan Perimeter holding action, the victory set in motion the moves which would shape the remainder of the war. MacArthur and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, pushed by US leaders in Washington, decided to aggressively pursue the shattered KPA into North Korea. The Eighth Army was ordered to advance as far north as possible to Manchuria and North Korea's border with China, with the primary objective of destroying what remained of the North Korean Army and the secondary objective of uniting all of Korea under Syngman Rhee.[207] This agitated China, which threatened that it would "not stand aside should the imperialists wantonly invade the territory of their neighbor."[208] Warnings from other nations not to cross the 38th Parallel went unheeded and MacArthur began the offensive into the country when North Korea refused to surrender.[209] This would eventually result in Chinese intervention once the UN troops reached the Yalu River, and what was originally known as the "Home By Christmas Offensive" turned into a war that would continue for another two-and-a-half years.[210]

References

Citations

^ abcde Fehrenbach 2001, p. 113.

^ abcd Appleman 1998, p. 395.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 605.

^ ab Ecker 2004, p. 32.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 546.

^ Varhola 2000, p. 3.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 1.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 2.

^ Varhola 2000, p. 2.

^ Catchpole 2001, p. 22.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 221.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 114.

^ ab Catchpole 2001, p. 24.

^ abc Catchpole 2001, p. 25.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 247.

^ abc Stewart 2005, p. 225.

^ abcd Stewart 2005, p. 226.

^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 116.

^ abc Fehrenbach 2001, p. 108.

^ Catchpole 2001, p. 19.

^ abc Appleman 1998, p. 254.

^ Catchpole 2001, p. 20.

^ abcd Appleman 1998, p. 253.

^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 109.

^ abc Appleman 1998, p. 255.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 262.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 263.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 264.

^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 114.

^ Marolda 2007, p. 14.

^ Marolda 2007, p. 15.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 126-127.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 133.

^ abcd Appleman 1998, p. 257.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 258.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 134.

^ Gough 1987, p. 60.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 114.

^ Gough 1987, p. 67.

^ Gough 1987, p. 57.

^ Gough 1987, p. 66.

^ Gough 1987, p. 69.

^ Gough 1987, p. 70.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 116.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 115.

^ Gough 1987, p. 76.

^ Shrader 1995, p. 13.

^ Shrader 1995, p. 18.

^ abc Shrader 1995, p. 5.

^ Shrader 1995, p. 20.

^ Shrader 1995, p. 10.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 377.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 256.

^ Shrader 1995, p. 3.

^ Shrader 1995, p. 4.

^ abcde Appleman 1998, p. 393.

^ abcdef Fehrenbach 2001, p. 136.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 135.

^ Millett 2000, p. 164.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 466.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 252.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 127.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 250.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 248.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 249.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 251.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 259.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 260.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 261.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 12.

^ ab Fehrenbach 2001, p. 120.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 289.

^ ab Ecker 2004, p. 11.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 126.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 265.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 267.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 269.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 128.

^ ab Fehrenbach 2001, p. 127.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 273.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 274.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 129.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 276.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 277.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 281.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 282.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 283.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 284.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 285.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 286.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 131.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 287.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 288.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 132.

^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 119.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 290.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 291.

^ ab Gugeler 2005, p. 30.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 293.

^ ab Fehrenbach 2001, p. 121.

^ abc Alexander 2003, p. 136.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 302.

^ ab Catchpole 2001, p. 26.

^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 130.

^ abc Fehrenbach 2001, p. 134.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 139.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 317.

^ abc Catchpole 2001, p. 27.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 140.

^ abc Appleman 1998, p. 319.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 320.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 321.

^ ab Fehrenbach 2001, p. 135.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 324.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 326.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 322.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 325.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 327.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 329.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 330.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 331.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 332.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 335.

^ abc Appleman 1998, p. 337.

^ Leckie 1996, p. 112.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 336.

^ ab Catchpole 2001, p. 31.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 338.

^ abcd Appleman 1998, p. 339.

^ ab Leckie 1996, p. 113.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 141.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 340.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 341.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 342.

^ abcde Alexander 2003, p. 142.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 344.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 352.

^ ab Fehrenbach 2001, p. 137.

^ abc Alexander 2003, p. 143.

^ abc Appleman 1998, p. 353.

^ ab Millett 2000, p. 506.

^ ab Varhola 2000, p. 6.

^ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 157.

^ ab Fehrenbach 2001, p. 138.

^ abcde Fehrenbach 2001, p. 139.

^ Catchpole 2001, p. 32.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 394.

^ ab Millett 2000, p. 507.

^ Millett 2000, p. 508.

^ abc Appleman 1998, p. 181.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 396.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 182.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 180.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 397.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 398.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 180.

^ Varhola 2000, p. 7.

^ Millett 2000, p. 557.

^ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 162.

^ Catchpole 2001, p. 36.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 416.

^ ab Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 176.

^ ab Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 175.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 13.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 17.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 18.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 21.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 20.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 22.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 23.

^ ab Ecker 2004, p. 24.

^ ab Ecker 2004, p. 25.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 28.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 37.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 38.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 583.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 14.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 16.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 26.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 27.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 29.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 30.

^ Ecker 2004, p. 39.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 602.

^ The Times, August 24, 1950.

^ The Times, August 29, 1950.

^ The Times, September 6, 1950.

^ The Times, August 14, 1950.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 604.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 345.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 347.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 435.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 349.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 240.

^ Millett 2010, p. 161.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 128.

^ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 145.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 144.

^ Millett 2010, p. 160.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 350.

^ Hanley & Jae-soon & December 6, 2008.

^ Bae & March 2, 2009.

^ Hanley, Choe & Mendoza 2001, p. 1.

^ Catchpole 2001, p. 33.

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 572.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 600.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 607.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 608.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 609.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 673.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Alexander, Bevin (2003). Korea: The First War We Lost. New York City, New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Appleman, Roy E. (1998). South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0.

Bowers, William T.; Hammong, William M.; MacGarrigle, George L. (2005). Black Soldier, White Army: The 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea. Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 978-1-4102-2467-5.

Catchpole, Brian (2001). The Korean War. London, United Kingdom: Robinson Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4.

Ecker, Richard E. (2004). Battles of the Korean War: A Chronology, with Unit-by-Unit United States Casualty Figures & Medal of Honor Citations. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-1980-7.

Fehrenbach, T.R. (2001). This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History (Fiftieth Anniversary ed.). Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-57488-334-3.

Gough, Terrence J. (1987). "U.S. Army and Logistics in the Korean War: a Research Approach" (PDF). CMH Pub 70-19. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

Gugeler, Russell A. (2005). Combat Actions in Korea. Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 978-1-4102-2451-4.

Hanley, Charles J.; Choe, Sang-Hun; Mendoza, Martha (2001). The Bridge at No Gun Ri: A Hidden Nightmare from the Korean War. New York City, New York: Henry Holt Publishings. ISBN 978-0-8050-6658-6.

Hoyt, Edwin P. (1984). On to the Yalu. New York City, New York: Stein and Day. ISBN 0-8128-2977-8.

Leckie, Robert (1996). Conflict: The History Of The Korean War, 1950–1953. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80716-9.

Marolda, Edward (2007). The US Navy in the Korean War. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-487-8.

Millett, Allan R. (2000). The Korean War, Volume 1. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7794-6.

Millett, Allan R. (2010). The War for Korea, 1950–1951: They Came from the North. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1709-8.

Paik, Sun Yup (1992). From Pusan to Panmunjom. Riverside, New Jersey: Brassey Inc. ISBN 0-02-881002-3.

Shrader, Charles R. (1995). Communist Logistics in the Korean War. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29509-3.

Stewart, Richard W. (2005). American Military History Volume II: The United States Army in a Global Era, 1917–2003. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. ISBN 978-0-16-072541-8.

Varhola, Michael J. (2000). Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953. Mason City, Iowa: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4.

Online sources

"Two War Reporters Killed". The Times. London, United Kingdom. August 14, 1950. ISSN 0140-0460.

"Royal Navy Rating Killed". The Times. London, United Kingdom. August 24, 1950. ISSN 0140-0460.

"British Troops Land". The Times. London, United Kingdom. August 29, 1950. ISSN 0140-0460.

"Far East Calsualties". The Times. London, United Kingdom. September 6, 1950. ISSN 0140-0460.

Hanley, Charles J.; Jae-soon Chang (December 6, 2008). "Children 'executed' in 1950 South Korean killings". Associated Press.

Bae Ji-sook (March 2, 2009). "Gov't Killed 3,400 Civilians During War". Korea Times. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

Coordinates: 35°06′N 129°02′E / 35.10°N 129.04°E / 35.10; 129.04