Battle of Inchon

The Battle of Inchon (Hangul: 인천상륙작전; Hanja: 仁川上陸作戰; RR: Incheon Sangryuk Jakjeon) was an amphibious invasion and battle of the Korean War that resulted in a decisive victory and strategic reversal in favor of the United Nations (UN). The operation involved some 75,000 troops and 261 naval vessels, and led to the recapture of the South Korean capital of Seoul two weeks later.[3] The code name for the operation was Operation Chromite.

The battle began on 15 September 1950 and ended on 19 September. Through a surprise amphibious assault far from the Pusan Perimeter that UN and South Korean forces were desperately defending, the largely undefended city of Incheon was secured after being bombed by UN forces. The battle ended a string of victories over the Korean People's Army (KPA). The subsequent UN recapture of Seoul partially severed the KPA's supply lines in South Korea.

The UN and South Korean forces were commanded by General of the Army Douglas MacArthur of the United States Army. MacArthur was the driving force behind the operation, overcoming the strong misgivings of more cautious generals to a risky assault over extremely unfavorable terrain.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Pusan Perimeter

1.2 Planning

2 Prelude

2.1 Maintaining surprise

2.2 Incheon infiltration

2.3 Bombardments of Wolmido and Incheon

2.4 Naval mine clearance

3 Battle

3.1 Green Beach

3.2 Red Beach

3.3 Blue Beach

3.4 Air attack on USS Rochester and HMS Kenya

4 Aftermath

4.1 Beachhead

4.2 Capture of Kimpo airfield

4.3 Battle of Seoul

4.4 Pusan Perimeter breakout

5 Analysis

6 In popular culture

7 Notes

8 References

9 External links

Background

Pusan Perimeter

From the outbreak of the Korean War following the invasion of South Korea by North Korea on 25 June 1950, the Korean People's Army (KPA), had enjoyed superiority in both manpower and equipment over the South Korean Army and United Nations (UN) forces dispatched to South Korea to prevent it from collapsing.[4] The North Korean strategy was to aggressively pursue UN and South Korean forces on all avenues of approach south and to engage them, attacking from the front and initiating a double envelopment of both flanks of the defending units, which allowed the North Koreans to surround and cut off the opposing force, forcing it to retreat in disarray.[5] From their initial 25 June offensive to fighting in July and early August, the North Koreans used this tactic to defeat the UN forces they encountered and push it south.[6] However, with the establishment of the Pusan Perimeter in August, UN forces held a continuous line which the North Koreans could not flank. The KPA advantages in numbers decreased daily as the superior UN logistical system brought in more troops and supplies to the UN forces.[7]

When the North Koreans approached the Pusan Perimeter on 5 August, they attempted the same frontal assault technique on the four main avenues of approach into the perimeter. Throughout August, they conducted direct assaults resulting in the Battle of Masan,[8] the Battle of Battle Mountain,[9] the First Battle of Naktong Bulge,[10][11] the Battle of Taegu,[12][13] and the Battle of the Bowling Alley.[14] On the east coast of the Korean Peninsula, the South Koreans repulsed three North Korean divisions at the Battle of P'ohang-dong.[15] The North Korean attacks stalled as UN forces repelled the attack.[16] All along the front, the North Korean troops reeled from these defeats, the first time in the war North Korean tactics had failed.[17]

By the end of August the North Korean troops had been pushed beyond their limits and many of the original units were at far reduced strength and effectiveness.[7][18] Logistic problems wracked the KPA, and shortages of food, weapons, equipment, and replacement soldiers proved devastating for North Korean units.[5][19] However, the North Korean force retained high morale and enough supply to allow for another large-scale offensive.[6] On 1 September the North Koreans threw their entire military into one final bid to break the Pusan Perimeter, the Great Naktong Offensive, a five-pronged simultaneous attack across the entire perimeter.[20] The attack caught UN forces by surprise and almost overwhelmed them.[21][22] North Korean troops attacked Kyongju,[23]surrounded Taegu[24] and Ka-san,[25] recrossed the Naktong Bulge,[26] threatened Yongsan,[27] and continued their attack at Masan, focusing on Nam River and Haman.[28] However, despite their efforts, in one of the most brutal fights of the Korean War, the North Koreans were unsuccessful.[29] Unable to hold their gains, the KPA retreated from the offensive a much weaker force, and vulnerable to counterattack.[30]

Planning

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur (center) grasps General J. Lawton Collins (the Army Chief of Staff, left) and Admiral Forrest Sherman (the Chief of Naval Operations, right) upon their arrival in Tokyo, Japan. MacArthur used their meeting to convince other military leaders that the assault on Incheon was necessary.

Days after the beginning of the war, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, the US Army officer in command of all UN forces in Korea, envisioned an amphibious assault to retake the Seoul area. The city had fallen in the first days of the war in the First Battle of Seoul.[31] MacArthur later wrote that he thought the North Korean army would push the Republic of Korea Army back far past Seoul.[32] He also said he decided days after the war began that the battered, demoralized, and under-equipped South Koreans, many of whom did not support the South Korean government put in power by the United States, could not hold off the North Korean forces even with American support. MacArthur felt that he could turn the tide if he made a decisive troop movement behind North Korean lines,[33] and preferred Inchon, now known as Incheon, over Chumunjin-up or Kunsan as the landing site. He had originally envisioned such a landing, code named Operation Bluehearts, for 22 July, with the US Army's 1st Cavalry Division landing at Incheon. However, by 10 July the plan was abandoned as it was clear the 1st Cavalry Division would be needed on the Pusan Perimeter.[34] On 23 July, MacArthur formulated a new plan, code-named Operation Chromite, calling for an amphibious assault by the US Army's 2nd Infantry Division and the United States Marine Corps's 5th Marine Regiment in mid-September 1950. This, too fell through as both units were moved to the Pusan Perimeter. MacArthur decided instead to use the US Army's 7th Infantry Division, his last reserve unit in East Asia, to conduct the operation as soon as it could be raised to wartime strength.[35]

In preparation for the invasion, MacArthur activated the US Army's X Corps to act as the command for the landing forces, and appointed Major General Edward Almond, his chief of staff, as corps commander, anticipating the operation would mean a quick end to the war.[36] Throughout August, MacArthur faced the challenge of re-equipping the 7th Infantry Division as it had sent 9,000 of its men to reinforce the Pusan Perimeter and was far understrength. He also faced the challenge that the US Marine Corps, reduced in size following World War II, had to rebuild the 1st Marine Division, using elements of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade fighting at Pusan as well as the 1st Marine Regiment and the 7th Marine Regiment, which pulled US Marines from as far away as the Mediterranean Sea to Korea for the task.[37] MacArthur ordered Korean Augmentation To the United States Army (KATUSA) troops, South Korean Army conscripts assigned to US Army units, to reinforce the 7th Infantry Division, while allocating all equipment coming into Korea to X Corps, despite it being crucially needed by the US Army's Eighth Army on the front lines.[38]

A Vought F4U-4B Corsair of Fighter Squadron 113 (VF-113) (the "Stingers") flies over UN ships off Inchon, Korea, on 15 September 1950. VF-113 was assigned to Carrier Air Group Eleven (CVG-11) aboard the aircraft carrier USS Philippine Sea (CV-47). The battleship USS Missouri (BB-63) is visible below the Corsair.

MacArthur decided to use the Joint Strategic and Operations Group (JSPOG) of his United States Far East Command (FECOM). The initial plan was met with skepticism by the other generals because Incheon's natural and artificial defenses were formidable. The approaches to Incheon were two restricted passages, which could be easily blocked by naval mines. The current of the channels was also dangerously quick – three to eight knots (3.5 to 9.2 mph; 5.5 to 14.8 km/hr). Finally, the anchorage was small and the harbor was surrounded by tall seawalls. United States Navy Commander Arlie G. Capps noted that the harbor had "every natural and geographic handicap."[39] US Navy leaders favored a landing at Kunsan, but MacArthur overruled these because he did not think they would be decisive enough for victory.[40] He also felt that the North Koreans, who also thought the conditions of the Incheon channel would make a landing impossible, would be surprised and caught off-guard by the attack.[41][42]

On 23 August, the commanders held a meeting at MacArthur's headquarters in Tokyo.[40]Chief of Staff of the United States Army General Joseph Lawton Collins, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Forrest Sherman, and United States Air Force operations deputy Lieutenant General Idwal H. Edward all flew from Washington, D.C., to Japan to take part in the briefing; Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force General Hoyt Vandenberg did not attend, possibly because he "did not want to legitimize an operation that essentially belong[ed] to the Navy and the Marines." The Marine Corps staff, who were to be responsible for leading the landing at Incheon, were not invited, which became a contentious issue. During the briefing, nine members of the staff of US Navy Admiral James H. Doyle spoke for nearly 90 minutes on every technical and military aspect of the landing.[43] MacArthur told the officers that though a landing at Kunsan would bring a relatively easy linkup with the Eighth Army, it "would be an attempted envelopment that would not envelop" and would place more troops in a vulnerable pocket of the Pusan Perimeter. MacArthur won over Sherman by speaking of his affection for the US Navy and relating the story of how the Navy carried him out of Corregidor to safety in 1942 during World War II. Sherman agreed to support the Incheon operation, leaving Doyle furious.[44]

The beach of Pohang in 2008. Here, UN forces landed unopposed in 1950

MacArthur spent 45 minutes after the briefing explaining his reasons for choosing Incheon.[45] He said that because it was so heavily defended, the North Koreans would not expect an attack there, that victory at Incheon would avoid a brutal winter campaign, and that, by invading a northern strong point, UN forces could cut off North Korean lines of supply and communication.[46] Sherman and Collins returned to Washington, D.C., and reported back to Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson. The Joint Chiefs of Staff approved MacArthur's plan on 28 August. President Truman also provided his approval.[47]

The landing at Incheon was not the first large-scale amphibious operation since World War II. That distinction belonged to the UN landing that took place on 18 July 1950 at Pohang, South Korea. However, that operation was not made in North Korean-held territory and was unopposed.[48]

Prelude

Before the main land battle, UN forces landed spies in Incheon and bombarded the city's defenses via air and sea. Deception operations were also carried out to draw North Korean attention away from Incheon.

Maintaining surprise

A United States Air Force 3rd Bombardment Group (Light) B-26 Invader conducts a rocket attack on the rail yard at Iri, South Korea, in early September 1950 as part of deception operations to draw North Korean attention away from the planned Inchon landings.

With men, supplies, and ships obviously concentrating at Pusan and in Japanese ports for a major amphibious operation and the press in Japan referring to the upcoming landings as "Operation Common Knowledge," the UN command feared that it would fail to achieve surprise in the Incheon landings. Exacerbating this fear, the leader of a North Korean-Japanese spy ring arrested in Japan in early September 1950 had a copy of the plan for Operation Chromite, and the UN forces did not know whether he had managed to transmit the plan to North Korea before his arrest. US Navy patrol aircraft, surface warships, and submarines operated in the Sea of Japan (East Sea) and the Yellow Sea to detect any reaction by North Korean, Soviet, or People's Republic of China military forces, and on 4 September 1950 F4U Corsair fighters of Fighter Squadron 53 (VF-53) operating from the aircraft carrier USS Valley Forge (CV-45) shot down a Soviet Air Force A-20 Havoc bomber after it opened fire on them over the Yellow Sea as it flew toward the UN naval task force there.[49]

In order to ensure surprise during the landings, UN forces staged an elaborate deception operation to draw North Korean attention away from Incheon by making it appear that the landing would take place 105 miles (169 km) to the south at Kunsan. On 5 September 1950, aircraft of the United States Air Force's Far East Air Forces began attacks on roads and bridges to isolate Kunsan, typical of the kind of raids expected prior to an invasion there.[49][50] A naval bombardment of Kunsan followed on 6 September, and on 11 September US Air Force B-29 Superfortress bombers joined the aerial campaign, bombing military installations in the area.[49]

In addition to aerial and naval bombardment, UN forces took other measures to focus North Korean attention on Kunsan. On the docks at Pusan, US Marine Corps officers briefed their men on an upcoming landing at Kunsan within earshot of many Koreans, and on the night of 12–13 September 1950 the Royal Navy frigate HMS Whitesand Bay (F633) landed US Army special operations troops and Royal Marine Commandos on the docks at Kunsan, making sure that North Korean forces noticed their visit.[49]

UN forces conducted a series of drills, tests, and raids elsewhere on the coast of Korea, where conditions were similar to Inchon, before the actual invasion. These drills were used to perfect the timing and performance of the landing craft,[48] but also were intended to confuse the North Koreans further as to the location of the invasion.

Incheon infiltration

Incheon, South Korea, in pink coloring.

Fourteen days before the landing at Incheon, a UN reconnaissance team landed in Incheon Harbor to obtain information on the conditions there. The team, led by US Navy Lieutenant Eugene F. Clark,[51] landed at Yonghung-do, an island in the mouth of the harbor. From there, the team relayed intelligence back to the UN Command. With the help of locals, Clark, gathered information about tides, beach composition, mudflats, and seawalls. A separate reconnaissance mission codenamed Trudy Jackson, which dispatched Lieutenant Youn Joung of the Republic of Korea Navy and South Korean Army Colonel Ke In-Ju to Incheon to collect further intelligence on the area, was mounted by the US military.[52]

The tides at Incheon have an average range of 29 feet (8.8 meters) and a maximum observed range of 36 feet (11 meters), making the tidal range there one of the largest in the world and the littoral maximum in all of Asia. Clark observed the tides at Incheon for two weeks and discovered that American tidal charts were inaccurate, but that Japanese charts were quite good.[53] Clark's team provided detailed reports on North Korean artillery positions and fortifications on the island of Wolmido, at Incheon, and on nearby islands. During the extensive periods of low tide, Clark's team located and removed some North Korean naval mines, but, critically to the future success of the invasion, Clark reported that the North Koreans had not in fact systematically mined the channels.[54]

When the North Koreans discovered that the agents had landed on the islands near Incheon, they made multiple attacks, including an attempted raid on Yonghung-do with six junks. Clark mounted a machine gun on a sampan and sank the attacking junks.[55] In response, the North Koreans killed perhaps as many as 50 civilians for helping Clark.[56]

Bombardments of Wolmido and Incheon

USS Rochester (CA-124) in 1956. She was the flagship of Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble off Incheon in 1950.

Wolmido under bombardment on 13 September 1950, two days before the landings, seen from the U.S. Navy destroyer USS Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729).

On 10 September 1950, five days before the Inchon landing, 43 American warplanes flew over Wolmido, dropping 93 napalm canisters to "burn out" its eastern slope in an attempt to clear the way for American troops.[57]

The flotilla of ships that landed and supported the amphibious force during the battle was commanded by Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble, an expert in amphibious warfare. Struble had participated in amphibious operations in World War II, including the Normandy landings and the Battle of Leyte.[58] He got underway for Incheon in his flagship, the heavy cruiser USS Rochester (CA-124), on 12 September 1950. Among his ships were the Gunfire Support Group, consisting of Rochester, the heavy cruiser USS Toledo (CA-133), the British light cruisers HMS Jamaica and HMS Kenya, and the six US destroyers of Task Element 90.62, made up of USS Collett (DD-730), USS De Haven (DD-727), USS Gurke (DD-783), USS Henderson (DD-785), USS Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729), and USS Mansfield (DD-728).[59]

As the landing groups neared, cruisers and destroyers from the United States and Canada shelled the fortifications on Wolmido and checked for mines in Flying Fish Channel. The first Canadian forces entered the Korean War when the Royal Canadian Navy destroyers HMCS Cayuga, HMCS Athabaskan, and HMCS Sioux bombarded the coast. The UN Fast Carrier Force offshore flew fighter cover, interdiction, and ground attack missions. Hundreds of Korean civilians were killed in these attacks on the lightly defended port.[citation needed]

The aft turret of the U.S. Navy heavy cruiser USS Toledo (CA-133) fires its 8-inch (203-mm) guns during the pre-invasion bombardment.

At 07:00 on 13 September, the US Navy's Destroyer Squadron Nine, headed by Mansfield, steamed up Eastern Channel and into Incheon Harbor, where it fired upon North Korean gun emplacements on Wolmido. Between them, the Canadian and American destroyers fired over a thousand 5-inch (127-mm) shells, inflicting severe damage on Wolmido's fortifications. The attacks tipped off the North Koreans that a landing might be imminent, and the North Korean officer in command on Wolmido assured his superiors that he would throw their enemies back into the sea.[60] North Korean artillery returned fire, inflicting significant damage on three of the attacking warships[citation needed], killing one sailor and wounding six others. Collett received the most damage; she took nine 75-millimeter-shell hits, which wounded five men. Gurke sustained three shell hits resulting in light damage and no casualties. The one dead man, David H. Swenson from Lyman K. Swenson, was later reported by the world media as being the nephew of Captain Lyman Knute Swenson, USS Lyman K. Swenson's namesake, but this was later found to be wrong.

The US Navy destroyer USS Collett (DD-730), photographed above in May 1944 while painted in dazzle camouflage, was among the ships damaged during the Wolmi-do bombardment.

The American destroyers withdrew after bombarding Wolmido for an hour and Rochester, Toledo, Jamaica, and Kenya proceeded to bombard the North Korean batteries for the next three hours from the south of the island. Lieutenant Clark and his South Korean squad watched from hills south of Incheon, plotting locations where North Korean machine guns were firing at the flotilla. They relayed this information to the invasion force via Japan in the afternoon.[61]

During the night of 13–14 September, Vice Admiral Struble decided on another day of bombardment, and the destroyers moved back up the channel off Wolmido on 14 September. They and the cruisers bombarded the island again that day, and planes from the carrier task force bombed and strafed it.

A tank landing ship enters the harbor at Incheon before the landings.

At 00:50 on 15 September 1950, Lieutenant Clark and his South Korean squad activated the lighthouse on the island of Palmido.[62] Later that morning, the ships carrying the amphibious force followed the destroyers toward Incheon and entered Flying Fish Channel, and the US Marines of the invasion force got ready to make the first landings on Wolmido.[63]

Within weeks of the outbreak of the Korean War, the Soviet Union had shipped naval mines to North Korea for use in coastal defense, with Soviet naval mine warfare experts providing technical instruction in laying and employment of the mines to North Korean personnel. Some of the mines were shipped to Incheon.[64] The UN forces only became aware of the presence of mines in North Korean waters in early September 1950, raising fears that this would interfere with the Incheon invasion. It was too late to reschedule the landings, but the North Koreans laid relatively few and unsophisticated mines at Incheon. Destroyers in the assault force visually identified moored contact mines in the channel at low tide and destroyed them with gunfire. When the invasion force passed through the channel at high tide to land on the assault beaches, it passed over any remaining mines without incident.[65]

Battle

The landing at Incheon.

Landing craft of the first and second waves approach Blue Beach on 15 September 1950. The U.S. Navy destroyer USS De Haven (DD-727), visible at bottom center, covers them.

Green Beach

The 31st Infantry lands at Inchon

At 06:30 on September 15, 1950, the lead elements of X Corps hit "Green Beach" on the northern side of Wolmido. The landing force consisted of the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, led by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Taplett and nine M26 Pershing tanks from the US Marine Corps' 1st Tank Battalion.[citation needed] One tank was equipped with a flamethrower and two others had bulldozer blades. The battle group landed from tank landing ships (LSTs). The entire island was captured by noon at the cost of just 14 casualties.[66]

The North Korean forces were outnumbered by more than six to one by the UN troops. North Korean casualties included over 200 killed and 136 captured, primarily from the 918th Artillery Regiment and the 226th Independent Marine Regiment.[67] The forces on Green Beach had to wait until 19:50 for the tide to rise, allowing another group to land. During this time, extensive shelling and bombing, along with anti-tank mines placed on the only bridge, kept the small North Korean force from launching a significant counterattack.[citation needed] The second wave came ashore at "Red Beach" and "Blue Beach".

The North Koreans had not been expecting an invasion at Incheon.[68] After the storming of Green Beach, the KPA assumed (probably because of deliberate American disinformation) that the main invasion would happen at Kunsan.[citation needed] As a result, only a small force was diverted to Incheon. Even those forces were too late, and they arrived after the UN forces had taken Blue Beach and Red Beach. The troops already stationed at Incheon had been weakened by Clark's guerrillas, and napalm bombing runs had destroyed key ammunition dumps. In total, 261 ships took part.[citation needed]

For Red Beach and Blue Beach, Vice Admiral James H. Doyle, Commander of an Amphibious ready group, announced that H-Hour, time of landing, would be 17:30.

The North Korean 22nd Infantry Regiment had moved to Incheon before dawn on September 15, 1950, but retreated to Seoul after the main landing that evening.[69]

Red Beach

General Douglas MacArthur (center), Commander in Chief of United Nations Forces, observes the shelling of lightly defended Incheon from the U.S. Navy amphibious force command ship USS Mount McKinley (AGC-7) on 15 September 1950.

Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez of the Marine Corps is shown scaling a seawall after landing on Red Beach (September 15). Minutes after this photo was taken, Lopez was killed after covering a live grenade with his body.[70] He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

The Red Beach forces, made up of the Regimental Combat Team 5, which included the 3rd Battalion of the Republic of Korea Marine Corps (ROKMC), used ladders to scale the sea walls. Lieutenant Colonel Raymond L. Murray, serving as Commanding Officer of the 5th Marines, had the mission of seizing an area three thousand yards long and a thousand yards deep, extending from Cemetery Hill (northern) at the top down to the Inner Tidal Basin (near Tidal Basin at the bottom) and including the promontory in the middle called Observatory Hill. (See Map) The 1st Battalion would be on the left, against Cemetery Hill and northern half of Observatory Hill. The 2nd Battalion would take the southern half of Observatory Hill and Inner Basin.[71]

Late on the afternoon of September 15, the LSTs approached Red Beach and as the lead ships they came under heavy mortar and machine gun fire from North Korean defenders on Cemetery Hill. Despite the concentrated fire, they disembarked assault troops and unloaded vital support equipment. In addition their guns wiped out North Korean batteries on the right flank of Red Beach. Three (LST 857, LST 859 and LST 973) of the eight LSTs took some hits from mortar and machine gun fire, which killed a sailor and injured a few others.[72] The LSTs completed unloading and cleared the beach at high tide early on 16 September.

After neutralizing North Korean defenses at Incheon on the night of September 15, they opened the causeway to Wolmi-do, allowing the 3rd Battalion of the 5th Marines and the tanks from Green Beach to enter the battle at Inchon. Early morning on September 16, the 5th Marines (Red and Green Beaches forces) entered the city of Inchon, taking it by the afternoon. On September 17, the 5th Marines ambushed a column of 6 KPA T-34 tanks and 200 infantry, inflicting heavy casualties on the North Koreans. By the night of the 17th, much of Kimpo Airfield had been taken; it was fully Marine-controlled by September 18.[citation needed][73]

Red Beach forces suffered eight dead and 28 wounded.[74]

Blue Beach

Under the command of Colonel Lewis Burwell "Chesty" Puller, the 1st Marine Regiment landing at Blue Beach was much farther south of the other two beaches and reached shore last. Their mission was to take the beachhead, and the road to Yongdungpo and Seoul. The 2nd Battalion would land on the left at Blue Beach One[75] and 3rd Battalion would land on Blue Beach Two. A little cove around the corner south of Blue Beach Two was called Blue Beach Three.[76] As they approached the coast, the combined fire from several NKPA gun emplacements sank one LST. Destroyer fire and bombing runs silenced the North Korean defenses. When the Blue Beach forces finally arrived, the North Korean forces at Incheon had already surrendered, so they met little opposition and suffered few casualties. The 1st Marine Regiment spent much of its time strengthening the beachhead and preparing for the inland invasion.

Air attack on USS Rochester and HMS Kenya

Just before daylight at 05:50 on 17 September, two Soviet-made North Korean aircraft – a Yakovlev Yak-9 and an Ilyushin Il-2 – made an attack run on Rochester while she was anchored off Wolmi-do. Initially the aircraft were thought to be friendly until they dropped four bombs over the American ship. All but one missed and the one that did hit dented Rochester's crane and failed to detonate. There were no American casualties in the skirmish. After the aircraft attacked Rochester, she and the nearby Jamaica opened fire on them with antiaircraft guns. The Il-2 then strafed Kenya, killing one sailor and wounding two. At about the same time, fire from Jamaica hit the Il-2 and it crashed into the water. The Yak-9 fled after losing its partner.[77][78][79]

Rochester's crew later painted a Purple Heart on her damaged crane.[80][81]

Aftermath

Beachhead

An abandoned Soviet-made North Korean 76 mm divisional gun M1942 (ZiS-3) on a hill overlooking Incheon harbor after its capture by United Nations forces.

Immediately after North Korean resistance was extinguished in Incheon, the supply and reinforcement process began. Seabees and Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs) that had arrived with the US Marines constructed a pontoon dock on Green Beach and cleared debris from the water. The dock was then used to unload the remainder of the LSTs. Early that morning of September 16, Lieutenant Colonel Murray and Colonel Puller had their operational orders from General Oliver P. Smith. The 1st Marines and 5th Marines began moving along the Inchon-Seoul road.

On September 16, the North Koreans, realizing their blunder, sent six columns of T-34 tanks to the beachhead. They were quite alone, without infantry support. They were spotted by a strike force of F4U Corsairs at the village of Kansong-ni, east of Inchon.[82] and two flights of F4U Corsairs from Marine Fighter Squadron 214 (VMF-214) bombed the attackers. The armored columns suffered extensive damage and the U.S. forces lost one airplane. A quick counter-attack by M26 Pershing tanks destroyed the remainder of the North Korean armored division and cleared the way for the capture of Incheon.

Capture of Kimpo airfield

An abandoned Soviet-made North Korean Ilyushin Il-10 attack aircraft captured by United Nations forces at Kimpo airfield in September 1950.

The Kimpo airfield was the largest and most important in Korea.[83] On September 17, General MacArthur was extremely urgent in his request for the early capture of Kimpo airfield. Once it was secured, the Fifth Air Force could bring fighters and bombers over from Japan to operate more easily against North Korea.[84] The attack on Kimpo airfield was carried out by 2nd Battalion 5th Marines.[85] That night at Kimpo, the North Koreans under the command of Brigadier General Wan Yong (the commander of the North Korean air force) were organizing their defense of the airfield. His troops were a conglomeration of half-trained fighting men and service forces. Several North Korean troops had already fled across the Han River toward Seoul to escape the fight. The North Koreans' defense was almost as bad as the morale of the men who realized that they were not going to get any help from the North Korean officials in Seoul.[86]

By morning the North Koreans were all gone, and Kimpo airfield was securely in the hands of the Marines. Kimpo airfield was in excellent shape; the North Koreans had not had time to do any major demolition. In fact, several North Korean planes were still on the field. Kimpo could now become the center of Allied land-based air operations.[87]

On September 19, US engineers repaired the local railroad up to eight miles (13 km) inland. After the capture of Kimpo airfield, transport planes began flying in gasoline and ordnance for the aircraft stationed there. The Marines continued unloading supplies and reinforcements. By September 22, they had unloaded 6,629 vehicles and 53,882 troops, along with 25,512 tons (23,000 tonnes) of supplies.[88]

Battle of Seoul

A Soviet-made North Korean T-34 tank knocked out by US Marines during the UN advance from Incheon to Seoul in September 1950

American M26 Pershing tanks in downtown Seoul during the Second Battle of Seoul. In the foreground, United Nations troops round up North Korean prisoners-of-war

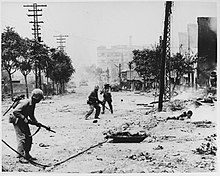

US Marines engaged in urban warfare during the battle for Seoul in late September 1950. The Marines are armed with an M1 rifle and an M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle. On the street are Korean civilians who died in the battle. In the distance are M4 Sherman tanks

In contrast to the quick victory at Incheon, the advance on Seoul was slow and bloody. The KPA launched another T-34 attack, which was trapped and destroyed, and a Yak bombing run in Incheon harbor, which did little damage. The KPA attempted to stall the UN offensive to allow time to reinforce Seoul and withdraw troops from the south.[citation needed] Though warned that the process of taking Seoul would allow remaining KPA forces in the south to escape, MacArthur felt that he was bound to honor promises given to the South Korean government to retake the capital as soon as possible.[citation needed]

On the second day, vessels carrying the US Army's 7th Infantry Division arrived in Incheon Harbor. Almond was eager to get the division into position to block a possible North Korean movement from the south of Seoul. On the morning of September 18, the division's 2nd Battalion of the 32nd Infantry Regiment landed at Incheon and the remainder of the regiment went ashore later in the day. The next morning, the 2nd Battalion moved up to relieve a U.S. Marine battalion occupying positions on the right flank south of Seoul. Meanwhile, the 7th Division's 31st Regiment came ashore at Incheon. Responsibility for the zone south of Seoul highway passed to 7th Division at 18:00 on September 19. The 7th Infantry Division then engaged in heavy fighting with North Korean soldiers on the outskirts of Seoul.

Before the battle, North Korea had just one understrength division in the city, with the majority of its forces south of the capital.[89] MacArthur personally oversaw the 1st Marine Regiment as it fought through North Korean positions on the road to Seoul. Control of Operation Chromite was then given to Almond, the X Corps commander. Almond was in an enormous hurry to capture Seoul by September 25, exactly three months after the North Korean assault across the 38th parallel.[90] On September 22, the Marines entered Seoul to find it fortified. Casualties mounted as the forces engaged in house-to-house fighting. On September 26, the Hotel Bando (which had served as the US Embassy) was cleared by Easy Company of 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment. During this fight several marines were wounded.[91]

Almond declared Seoul liberated the evening of September 25, a claim repeated by MacArthur the following day. However, at the time of Almond's declaration, US Marines were still engaged in house-to-house combat as the KPA remained in most of the city. It was not until September 28 that the last of the KPA elements were driven out or destroyed.[92]

Pusan Perimeter breakout

Meanwhile, 5th Marines came ashore at Inchon. The last North Korean troops in South Korea still fighting were defeated when Walton H. Walker's 8th Army broke out of the Pusan Perimeter, joining the Army's X Corps in a coordinated attack on NKPA forces. Of the 70,000 NKPA troops around Pusan, in the aftermath of the Pusan Perimeter battle, North Korean casualties from September 1 to September 15 could range from roughly 36,000 to 41,000 killed and captured, with an unknown total number of wounded.[93] However, because UN forces had concentrated on taking Seoul rather than cutting off the NKPA's withdrawal north, the remaining 30,000 North Korean soldiers escaped to the north, where they were soon reconstituted as a cadre for the formation of new NKPA divisions hastily re-equipped by the Soviet Union. The allied assault continued north to the Yalu River until the intervention of the People's Republic of China in the war in November 1950.

Analysis

Most military scholars consider the battle one of the most decisive military operations in modern warfare. Spencer C. Tucker, the American military historian, described the Inchon landings as "a brilliant success, almost flawlessly executed," which remained "the only unambiguously successful, large-scale US combat operation" for the next 40 years.[94] Commentators have described the Inchon operation as MacArthur's "greatest success"[95] and "an example of brilliant generalship and military genius."[96]

However, Russell Stolfi argues that the landing itself was a strategic masterpiece but it was followed by an advance to Seoul in ground battle so slow and measured that it constituted an operational disaster, largely negating the successful landing. He contrasts the US military's 1950 Incheon-Seoul operation with the German offensive in the Baltic in 1941. American forces achieved a strategic masterpiece in the Incheon landing in September 1950 and then largely negated it by a slow, tentative, 11-day advance on Seoul, only twenty miles away. By contrast, in the Baltic region in 1941 the German forces achieved strategic surprise in the first day of their offensive and then, exhibiting a breakthrough mentality, pushed forward rapidly, seizing key positions and advancing almost two hundred miles in four days. The American advance was characterized by cautious, restrictive orders, concerns about phase lines, limited reconnaissance, and command posts well in the rear, while the Germans positioned their leaders as far forward as possible, relied on oral or short written orders, reorganized combat groups to meet immediate circumstances, and engaged in vigorous reconnaissance.[97]

In popular culture

Inchon (1981), directed by Terence Young with Laurence Olivier as General Douglas MacArthur. Unification Church founder Sun Myung Moon was an executive producer of the film.[98]

Operation Chromite (2016), directed by John H. Lee (Lee Jae-han). Starring Lee Jung-jae, Lee Beom-soo, and Liam Neeson as General MacArthur.[99]

Notes

^ Halberstam 2007, p. 302

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 11 They did not anticipate any air opposition for, as far as intelligence knew, the North Koreans had only nineteen planes left.

^ The Independent, 16 September 2010, p.35 reporting on a 60th anniversary re-enactment.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 392.

^ ab Varhola 2000, p. 6.

^ ab Fehrenbach 2001, p. 138

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 393.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 367.

^ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 149

^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 130

^ Alexander 2003, p. 139.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 353.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 143.

^ Catchpole 2001, p. 31

^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 136

^ Appleman 1998, p. 369.

^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 135

^ Millett 2000, p. 506

^ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 157

^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 139

^ Alexander 2003, p. 180.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 180.

^ Millett 2000, p. 557

^ Appleman 1998, p. 411.

^ Fehrenbach 2001, p. 140

^ Appleman 1998, p. 443.

^ Millett 2000, p. 532

^ Bowers, Hammong & MacGarrigle 2005, p. 158

^ Varhola 2000, p. 7.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 600.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 488.

^ MacArthur 1964, p. 333.

^ MacArthur 1964, p. 350.

^ Halberstam 2007, pp. 294–295.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 489.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 490.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 491.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 492.

^ Marolda 2007, p. 68

^ ab Appleman 1998, p. 493.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 494.

^ Halberstam 2007, p. 299.

^ Halberstam 2007, pp. 298–299.

^ Halberstam 2007, p. 300.

^ Utz 1994, p. 18

^ MacArthur 1964, pp. 349–350.

^ Korea Institute of Military History 2000, p. 601.

^ ab "Landings By Sea Not New In Korea", The New York Times, p. 3, September 15, 1950.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcd Utz 1994, pp. 20–22

^ Korea Institute of Military History 2000, p. 610.

^ Clark later published a book, The Secrets of Inchon: The Untold Story of the Most Daring Covert Mission of the Korean War, an account of his exploits at Incheon.

^ Korea Institute of Military History 2000, pp. 609–610.

^ Francis E. Wylie, Tides and the Pull of the Moon, p. 214 et seq. The Stephen Greene Press, Brattleboro, Vermont, 1979

^ Shaw, Ronald, Reinventing Amphibious Hydrography: The Inchon Assault and Hydrographic Support for Amphibious Operations, 2008, Naval War College, Newport, RI, p. 4-5

^ Clark 2002, pp. 216–222

^ Fleming, Thomas, epilogue to The Secrets of Inchon, 2002, p. 323

^ Choe, Sang-Hun (August 3, 2008), "South Korea Says U.S. Killed Hundreds of Civilians", New York Times

^ Parrott, Lindesay (September 18, 1950), "United States Marines Headed For Seoul", The New York Times, p. 1

^ Schelling, Robert. "Captain". USS DEHAVEN, Six Sitting Ducks.

^ Utz 1994, p. 25

^ Clark 2002, pp. 294

^ Clark 2002, pp. 419, 430

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 13

^ Melia, Tamara Moser, "Damn the Torpedoes:" A Short History of U.S. Naval Mines Countermeasures, 1777–1991, Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy, Washington, D.C., 1991, p. 72.

^ Melia, Tamara Moser, "Damn the Torpedoes:" A Short History of U.S. Naval Mines Countermeasures, 1777–1991, Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy, Washington, D.C., 1991, p. 73.

^ Alexander, Joseph H.; Horan, Don (1999), The Battle History of the U.S. Marines: A Fellowship of Valor, New York: HarperCollins, p. v, ISBN 0-06-093109-4

^ Gammons, Stephen L.Y. The Korean War: The UN Offensive. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 19-7. Archived from the original on 2014-07-13.

^ Clark 2002, pp. 206, 280

^ "The Korean War: The UN Offensive". www.army.mil.

^ "The Incheon Invasion, September 1950: Overview and Selected Images" from Naval Historical Center and " First Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez, USMC" from US Marine Corps Archived 2007-04-30 at the Wayback Machine

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 20

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 31

^ Sheldon, Walt (1973-01-01). Hell Or High Water: MacArthur's Landing at Inchon. Ballantine Books.

^ Korea Institute of Military History 2000, p. 615.

^ "Map". Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 28

^ "Account of Jamaica in the Korean War". Archived from the original on 2010-11-20.

^ "Korean War Naval Chronology June–December 1950". Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 16 August 2000. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

^ [1] Archived May 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

^ "The Graybeards" (PDF). The Graybeards Korean War Veterans Association. Korean War Veterans Association. Oct 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

^ MA, Concord,. "Concord, MA - April 2005". www.concordma.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-06-07. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 34

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 36

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 56

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 58

^ Hoyt 1984, pp. 58–59

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 61

^ Over-the-Beach Logistics, U.S. Navy History.

^ Baldwin, Hanson W. (September 27, 1950), "Invasion Gamble Pays", The New York Times, p. 6, retrieved June 18, 2006

^ Hoyt 1984, p. 77

^ Longabardi, Eric; Roane, Kit; Pound, Edward (November 3, 2003), "A War of Memories", U.S. News & World Report, p. 33, archived from the original on September 29, 2008,Garabedian describes a hellish, dangerous moment. Marines rushed through the building, going from room to room, bursting in on the North Korean forces shooting from the windows. Several marines were wounded, he says, as the squads ran through the hallways, killing some of the North Koreans. Garabedian recalls being on the second floor of the building. He set up by a window and had a view up and down the building's staircase. As some marines continued to clear out the building, others took prisoners down the stairwell to another marine in a bath area. There were about 12 prisoners. The marine in charge was guarding them with his Browning automatic rifle. All were forced to strip to make sure none still had weapons.

^ Blair 1987, p. 293.

^ Appleman 1998, p. 604

^ Spencer C. Tucker, "Inchon Landings, 1950" in The Korean War: An Encyclopedia (ed. Stanley Sandler), Routledge (1996), p. 145.

^ Michael D. Pearlman, Douglas MacArthur and the Advance to the Yalu, November 1950, in Studies in Battle Command, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, p. 137

^ Robert O. Brunson, The Inchon Landing: An Example of Brilliant Generalship, U.S. Army War College Strategy Research Project (April 7, 2003).

^ Stolfi, Russel H. S. (2004), "A Critique of Pure Success: Incheon Revisited, Revised, and Contrasted", Journal of Military History, 68 (2): 505–525, doi:10.1353/jmh.2004.0075, ISSN 0899-3718

^ "Inchon (1981)". IMDb. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

^ "Operation Chromite (2016)". IMDb. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Alexander, Bevin (2003). Korea: The First War We Lost. New York City, New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7.

Appleman, Roy E. (1998). South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0.

Blair, Clay (1987). The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950–1953. New York: Times Books. ISBN 0-8129-1670-0.

Bowers, William T.; Hammong, William M.; MacGarrigle, George L. (2005), Black Soldier, White Army: The 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea, Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 978-1-4102-2467-5

Catchpole, Brian (2001), The Korean War, London, United Kingdom: Robinson Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4

Clark, Eugene Franklin (2002), The Secrets of Inchon: The Untold Story of the Most Daring Covert Mission of the Korean War, Putnam Pub Group, ISBN 0-399-14871-X

Fehrenbach, T.R. (2001), This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History – Fiftieth Anniversary Edition, Washington D.C.: Potomac Books, ISBN 978-1-57488-334-3

Halberstam, David (2007). The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4013-0052-4.

Hoyt, Edwin P. (1984), On to the Yalu, New York: Stein and Day, ISBN 0-8128-2977-8

Korea Institute of Military History (2000). The Korean War. 1. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7794-6.

Krulak, Victor H. (Lt. Gen.) (1999), First to Fight: An Inside View of the U.S. Marine Corps, Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-55750-464-7

MacArthur, Douglas (1964). Reminiscences. New York City, New York: Ishi Press. ISBN 978-4-87187-882-1.

Marolda, Edward (2007), The US Navy in the Korean War, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-59114-487-8

Millett, Allan R. (2000), The Korean War, Volume 1, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-7794-6

Utz, Curtis (1994), Assault from the Sea: The Amphibious Landing at Inchon, Washington DC: Naval Historical Center, ISBN 978-0-16-045271-0, archived from the original on 2004-10-17

Varhola, Michael J. (2000). Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953. Mason City, Iowa: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Inchon. |

- Max Hermansen (2000) "Inchon – Operation Chromite"

Invasions of Inchon and Wonsan remembered French and English supported operations. Allies provide a unique perspective of naval operation in the Korean War.

"Operation Inchon: Korean War Amphibious Assault" on YouTube

Coordinates: 37°29′N 126°38′E / 37.483°N 126.633°E / 37.483; 126.633 (Inchon)