Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke

| Regents of the University of California v. Bakke | |

|---|---|

Supreme Court of the United States | |

| Argued October 12, 1977 Decided June 28, 1978 | |

| Full case name | Regents of the University of California v. Allan Bakke |

| Citations | 438 U.S. 265 (more) 98 S. Ct. 2733; 57 L. Ed. 2d 750; 1978 U.S. LEXIS 5; 17 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 1000; 17 Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH) ¶ 8402 |

| Prior history | Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California, Bakke v. Regents of the University of California, 18 Cal. 3d 34, 132 Cal. Rptr. 680, 553 P.2d 1152, 1976 Cal. LEXIS 336 (1976) |

| Holding | |

| Bakke was ordered admitted to UC Davis Medical School, and the school's practice of reserving 16 seats for minority students was struck down. Judgment of the Supreme Court of California reversed insofar as it forbade the university from taking race into account in admissions. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Powell (Parts I and V-C), joined by Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun. Burger, Stewart, Rehnquist, and Stevens joined in the part of the judgment finding UC Davis's affirmative action program unconstitutional and ordering Bakke admitted. |

| Plurality | Powell (Part III-A), joined by White |

| Concur/dissent | Brennan |

| Concur/dissent | White |

| Concur/dissent | Marshall |

| Concur/dissent | Blackmun |

| Concur/dissent | Stevens, joined by Burger, Stewart, Rehnquist |

| Laws applied | |

U.S. Const. amend. XIV Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 | |

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978),[1] was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States. It upheld affirmative action, allowing race to be one of several factors in college admission policy. However, the court ruled that specific racial quotas, such as the 16 out of 100 seats set aside for minority students by the University of California, Davis School of Medicine, were impermissible.

Although the Supreme Court had outlawed segregation in schools, and had even ordered school districts to take steps to assure integration, the question of the legality of voluntary affirmative action programs initiated by universities remained unresolved. Proponents deemed such programs necessary to make up for past discrimination, while opponents believed they were illegal and a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. An earlier case that the Supreme Court had taken in an attempt to address the issue, DeFunis v. Odegaard (1974), was dismissed on procedural grounds.

Allan P. Bakke (/ˈbɑːkiː/), an engineer and former United States Marine Corps officer, sought admission to medical school, but was rejected for admission by several due in part to his age. Bakke was in his early 30s while applying, and therefore considered too old by at least two institutions. After twice being rejected by the University of California, Davis, he brought suit in state court. The California Supreme Court struck down the program as violative of the rights of white applicants and ordered Bakke admitted. The U.S. Supreme Court accepted the case amid wide public attention.

The case fractured the court; the nine justices issued a total of six opinions. The judgment of the court was written by Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr.; two different blocs of four justices joined various parts of Powell's opinion. Finding diversity in the classroom to be a compelling state interest, Powell opined that affirmative action in general was allowed under the Constitution and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Nevertheless, UC Davis's program went too far for a majority of justices, and it was struck down and Bakke admitted. The practical effect of Bakke was that most affirmative action programs continued without change. Questions about whether the Bakke case was merely a plurality opinion or binding precedent were answered in 2003 when the court upheld Powell's position in a majority opinion in Grutter v. Bollinger.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 State of the law

1.2 Allan Bakke

1.3 Lower court history

2 U.S. Supreme Court consideration

2.1 Acceptance and briefs

2.2 Argument and deliberation

2.3 Decision

2.3.1 Powell's opinion

2.3.2 Other opinions

3 Reaction

4 Aftermath

5 See also

6 Notes and references

6.1 Bibliography

7 External links

Background

State of the law

In Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Supreme Court of the United States ruled segregation by race in public schools to be unconstitutional. In the following fifteen years, the court issued landmark rulings in cases involving race and civil liberties, but left supervision of the desegregation of Southern schools mostly to lower courts.[2] Among other progressive legislation, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[3] Title VI of which forbids racial discrimination in any program or activity receiving federal funding.[4] By 1968, integration of public schools was well advanced. In that year, the Supreme Court revisited the issue of school desegregation in Green v. County School Board, ruling that it was not enough to eliminate racially discriminatory practices; state governments were under an obligation to actively work to desegregate schools.[5][6] The school board in Green had allowed children to attend any school, but few chose to attend those dominated by another race.[7] In 1970, in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, the Supreme Court upheld an order for busing of students to desegregate a school system.[5][8]

Although public universities were integrated by court decree, selective colleges and graduate programs, and the professions which stemmed from them, remained almost all white. Many African-Americans had attended inferior schools and were ill-prepared to compete in the admissions process. This was unsatisfactory to many activists of the late 1960s, who protested that given the African-American's history of discrimination and poverty, some preference should be given to minorities. This became a commonly held liberal position, and large numbers of public and private universities began affirmative action programs.[9] Among these were the University of California, Davis School of Medicine (UC Davis or "the university"), which was founded in 1968 and had an all-white inaugural class. The faculty was concerned by this, and the school began a special admissions program "to compensate victims of unjust societal discrimination".[10][11] The application form contained a question asking if the student wished to be considered disadvantaged, and, if so, these candidates were screened by a special committee, on which more than half the members were from minority groups.[12] Initially, the entering class was 50 students, and eight seats were put aside for minorities; when the class size doubled in 1971, there were 16 seats which were to be filled by candidates recommended by the special committee.[13] While nominally open to whites, no one of that race was admitted under the program, which was unusual in that a specific number of seats were to be filled by candidates through this program.[10]

The first case taken by the Supreme Court on the subject of the constitutionality of affirmative action in higher education was DeFunis v. Odegaard (1974).[14][15] Marco DeFunis, a white man, had twice been denied admission to the University of Washington School of Law. The law school maintained an affirmative action program, and DeFunis had been given a higher rating by admissions office staff than some admitted minority candidates. The Washington state trial court ordered DeFunis admitted, and he attended law school while the case was pending. The Washington Supreme Court reversed the trial court, but the order was stayed, and DeFunis remained in school. The U.S. Supreme Court granted review and the case was briefed and argued, but by then, DeFunis was within months of graduation. The law school stated in its briefs that even if it won, it would not dismiss him.[14][16] After further briefing on the question of mootness, the Supreme Court dismissed the case, 5-4, holding that as DeFunis had almost completed his studies, there was no longer a case or controversy to decide.[14][17] Justice William Brennan, in an opinion joined by the other three members of the minority, accused the court of "sidestepping" the issues, which "must inevitably return to the federal courts and ultimately again to this court".[14][18]

Allan Bakke

Allan Paul Bakke (born 1940),[19] a 35-year-old white male, applied to twelve medical schools in 1973. He had been a National Merit Scholar at Coral Gables Senior High School, in Florida. He was accepted as an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota, deferring tuition costs by joining Naval ROTC. He graduated from the University of Minnesota with a grade-point average (GPA) of 3.51. In order to fulfill his ROTC requirements, he joined the Marine Corps and served four years, including a seven-month tour of duty in Vietnam as a commanding officer of an anti-aircraft battery. In 1967, having achieved the rank of captain, he was granted an honorable discharge.[20] Bakke then worked as an engineer at NASA. He stated that his interest in medicine started in Vietnam, and increased at NASA, as he had to consider the problems of space flight and the human body there. But twelve medical schools rejected his application for admission.[21]

Bakke had applied first to the University of Southern California and Northwestern University, in 1972, and both rejected him, making a point of his age, with Northwestern writing that it was above their limit.[21] Medical schools at the time openly practiced age discrimination.[22]

Bakke applied late to UC Davis in 1973 because his mother-in-law was ill.[23][24] This delay may well have cost him admission: although his credentials were outstanding even among applicants not part of the special program, by the time his candidacy was considered under the school's rolling admissions process, there were few seats left.[25] His application reflected his anxiety about his age, referring to his years of sacrifice for his country as a cause of his interest in medicine.[21]

Bakke received 468 points out of a possible 500 on the admissions committee’s rating scale in 1973. Earlier in the year, a rating of 470 had won automatic admission with some promising applicants being admitted with lower scores. Bakke had a science GPA of 3.44 and an overall GPA of 3.46 after taking science courses at night to qualify for medical school. On the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT), Bakke scored in the 97th percentile in scientific knowledge, the 96th percentile in verbal ability, the 94th percentile in quantitative analysis, and the 72nd percentile in general knowledge.[20][26] Bakke's MCAT score overall was 72; the average applicant to UC Davis scored a 69 and the average applicant under the special program a 33.[27] In March 1973, Bakke was invited to UC Davis for an interview. Dr. Theodore West, who met with him, described Bakke as “a well-qualified candidate for admission whose main hardship is the unavoidable fact that he is now 33. … On the grounds of motivation, academic records, potential promise, endorsement by persons capable of reasonable judgments, personal appearance and decorum, maturity, and probable contribution to balance in the class, I believe Mr. Bakke must be considered as a very desirable applicant and I shall so recommend him.”[26][28] About two months later in May 1973, Bakke received notice of his rejection.[20][21]

Bakke complained to Dr. George Lowrey, chairman of the admissions committee at the medical school, about the special admissions program. At Lowrey's request, Assistant Dean Peter Storandt told Bakke his candidacy had come close and encouraged him to reapply. If he was not accepted the second time, "he could then research the legal question. He had been a good candidate. I thought he'd be accepted and that would end the matter."[29] Storandt also gave Bakke the names of two lawyers interested in the issue of affirmative action.[20] The general counsel for the University of California said, "I don't think Storandt meant to injure the university. It's simply an example of a non-lawyer advising on legal matters."[29] Storandt stated, "I simply gave Allan the response you'd give an irate customer, to try and cool his anger. I realized the university might be vulnerable to legal attack because of its quota, and I had the feeling by then that somebody somewhere would sue the school, but I surely didn't know this would be the case."[29] Storandt was demoted and later left the university. According to Bernard Schwartz in his account of the Bakke case, Storandt was fired.[29][30]

Allan Bakke applied to UC Davis medical school again in 1974.[21] He was interviewed twice: once by a student interviewer, who recommended his admission, and once by Dr. Lowrey, who in his report stated that Bakke "had very definite opinions which were based more on his personal viewpoints than on a study of the whole problem … He was very unsympathetic to the concept of recruiting minority students."[31] Lowrey gave Bakke a poor evaluation, the only part of his application on which he did not have a high score.[32] He was rejected again, although minorities were admitted in both years with significantly lower academic scores through the special program. Not all minority applicants whose admission was recommended under the program gained entry—some were rejected by the admissions committee. This, however, did not affect the number of minority students to be admitted, sixteen.[21][33] Although 272 white people between 1971 and 1974 had applied under this program, none had been successful;[20] in 1974 the special admissions committee summarily rejected all white students who asked for admission under the program. Only one black student and six Latinos were admitted under the regular admissions program in that time period, though significant numbers of Asian students were given entry.[34]

According to a 1976 Los Angeles Times article, the dean of the medical school sometimes intervened on behalf of daughters and sons of the university's "special friends" in order to improve their chances.[35] Among those who benefitted by Dean C. John Tupper's interventions (about five per year) was the son of an influential state assemblyman, who had not even filed an application. The special picks were ended by order of University of California President David S. Saxon in 1976. Bakke's lawyer deemed it impossible to tell if these picks caused Bakke not to be admitted, but according to an attorney who filed an amicus curiae brief on behalf of the National Urban League in support of affirmative action, the practice of dean's picks made the university reluctant to go into detail about its admission practices at trial, affecting its case negatively.[36]

Lower court history

On June 20, 1974,[37] following his second rejection from UC Davis, Bakke brought suit against the university's governing board in the Superior Court of California,[33]Yolo County. He sought an order admitting him on the ground that the special admission programs for minorities violated the U.S. and California constitutions, and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. UC Davis's counsel filed a request that the judge, F. Leslie Manker, find that the special program was constitutional and legal, and argued that Bakke would not have been admitted even if there had been no seats set aside for minorities. On November 20, 1974, Judge Manker found the program unconstitutional and in violation of Title VI, "no race or ethnic group should ever be granted privileges or immunities not given to every other race."[38] Manker ordered the medical school to disregard race as a factor, and to reconsider Bakke's application under a race-free system.[39] After Manker entered final judgment in the case on March 7, 1975,[37] both parties appealed, the university on March 20 because the program was struck down, and Bakke on April 17 because he was not ordered admitted.[37][39]

Because of the important issues presented, the Supreme Court of California on June 26, 1975 ordered the appeal transferred to it, bypassing the intermediate appeals court.[40][41] On March 19, 1976, the case was argued before the state supreme court.[42] Nine amicus curiae briefs were filed by various organizations, the majority in support of the university's position.[43] The California Supreme Court was considered one of the most liberal appellate courts, and it was widely expected that it would find the program to be legal. Nevertheless, on September 16, 1976, the court, in an opinion by Justice Stanley Mosk, upheld the lower-court ruling, 6–1.[37][43][44] Mosk wrote that "no applicant may be rejected because of his race, in favor of another who is less qualified, as measured by standards applied without regard to race".[45][46] Justice Matthew O. Tobriner dissented, stating that Mosk's suggestion that the state open more medical schools to accommodate both white and minority was unrealistic due to cost: "It is a cruel hoax to deny minorities participation in the medical profession on the basis of such fanciful speculation."[47][48] The court barred the university from using race in the admissions process and ordered it to provide evidence that Bakke would not have been admitted under a race-neutral program. When the university conceded its inability to do so in a petition for rehearing, the court on October 28, 1976 amended its ruling to order Bakke's admission and denied the petition.[37][49][50]

U.S. Supreme Court consideration

Acceptance and briefs

Students protest at a meeting of the Regents of the University of California, June 20, 1977

The university requested that the U.S. Supreme Court stay the order requiring Bakke's admission pending its filing a petition asking for review. U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Rehnquist, as circuit justice for the Ninth Circuit (which includes California) granted the stay for the court in November 1976.[51][52]

The university filed a petition for writ of certiorari in December 1976.[52] The papers of some of the justices who participated in the Bakke case reveal that the case was three times considered by the court in January and February 1977. Four votes were needed for the court to grant certiorari, and it had at least that number each time, but was twice put over for reconsideration at the request of one of the justices. A number of civil rights organizations filed a joint brief as amicus curiae, urging the court to deny review, on the grounds that the Bakke trial had failed to fully develop the issues—the university had not introduced evidence of past discrimination, or of bias in the MCAT. Nevertheless, on February 22, the court granted certiorari, with the case to be argued in its October 1977 term.[53][54]

Protest against the California Supreme Court's decision in Bakke, Los Angeles, May 7, 1977

The parties duly filed their briefs. The university's legal team was now headed by former U.S. Solicitor General and Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox, who had argued many cases before the Supreme Court. Cox wrote much of the brief, and contended in it that "the outcome of this controversy will decide for future generations whether blacks, Chicanos and other insular minorities are to have meaningful access to higher education and real opportunities to enter the learned professions".[55] The university also took the position that Bakke had been rejected because he was unqualified.[56] Reynold Colvin, for Bakke, argued that his client's rights under the Fourteenth Amendment to equal protection of the laws had been violated by the special admission program.[57] Fifty-eight amicus curiae briefs were filed, establishing a record for the Supreme Court that would stand until broken in the 1989 abortion case Webster v. Reproductive Health Services. Future justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg signed the ACLU's brief; Marco deFunis, the petitioner in the 1974 case dismissed for mootness, wrote the brief for Young Americans for Freedom.[58]

In addition to the various other amici, the United States filed a brief through the Solicitor General, as it may without leave of court under the Supreme Court's rules. When consideration of Bakke began in the new administration of President Jimmy Carter, early drafts of the brief both supported affirmative action and indicated that the program should be struck down and Bakke admitted. This stance reflected the mixed support of affirmative action at that time by the Democrats. Minorities and others in that party complained, and in late July 1977, Carter announced that the government's brief would firmly support affirmative action. That document, filed October 3, 1977 (nine days before oral argument), stated that the government supported programs tailored to make up for past discrimination, but opposed rigid set-asides.[59] The United States urged the court to remand the case to allow for further fact-finding (a position also taken by civil rights groups in their amicus briefs).[59]

While the case was awaiting argument, another white student, Rita Clancy, sued for admission to UC Davis Medical School on the same grounds as Bakke had. In September 1977, she was ordered admitted pending the outcome of the Bakke case. After Bakke was decided, the university dropped efforts to oust her, stating that as she had successfully completed one year of medical school, she should remain.[60]

Argument and deliberation

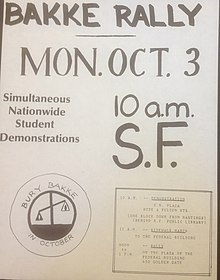

Poster for rally urging that affirmative action be upheld in Bakke, October 1977

Oral argument in Bakke took place on October 12, 1977. There was intense public interest in the case; prospective attendees began to line up the afternoon before. The court session took two hours, with Cox arguing for the university, Colvin for Bakke, and Solicitor General Wade H. McCree for the United States.[61] Colvin was admonished by Justice Byron White for arguing the facts, rather than the Constitution.[62] Cox provided one of the few moments of levity during the argument when Justice Harry A. Blackmun wondered whether the set-aside seats could be compared to athletic scholarships. Cox was willing to agree, but noted that he was a Harvard graduate, and as for sporting success, "I don't know whether it's our aim, but we don't do very well."[63]

Thurgood Marshall on Bakke

Beginning the day after the argument, the justices lobbied each other through written memorandum.[64] At a conference held among justices on October 15, 1977, they decided to request further briefing from the parties on the applicability of Title VI.[65] The supplemental brief for the university was filed on November 16, and argued that Title VI was a statutory version of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and did not allow private plaintiffs, such as Bakke, to pursue a claim under it. Bakke's brief arrived the following day. Colvin submitted that Bakke did have a private right of action, and that his client did not want the university to suffer the remedy prescribed under Title VI for discriminatory institutions—loss of federal funding—but wanted to be admitted.[66] In November, Justice Blackmun left Washington to have prostate surgery at the Mayo Clinic.[67]

Blackmun's absence did not stem the flow of memos, notably one on November 22 from Justice Lewis Powell, analyzing the minority admissions program under the strict scrutiny standard often applied when government treats some citizens differently from others based on a suspect classification such as race. Concluding that the program did not meet the standard, and must be struck down, Powell's memorandum stated that affirmative action was permissible under some circumstances, and eventually formed much of his released opinion.[68]

At the justices' December 9 conference, with Blackmun still absent, they considered the case. Counting heads, four justices (Chief Justice Warren E. Burger and Justices Potter Stewart, Rehnquist, and John Paul Stevens) favored affirming the California Supreme Court's decision. Three (Justices Brennan, White, and Thurgood Marshall) wanted to uphold the program. Justice Blackmun had not yet weighed in. Powell stated his views, after which Brennan, hoping to cobble together a five-justice majority to support the program, or at least to support the general principle of affirmative action, suggested to Powell that applying Powell's standard meant that the lower court decision would be affirmed in part and reversed in part. Powell agreed.[69]

Even when Blackmun returned in early 1978, he was slow to make his position on Bakke known. It was not until May 1 that he circulated a memorandum to his colleagues's chambers, indicating that he would join Brennan's bloc, in support of affirmative action and the university's program. This meant that Powell was essential to either side being part of a majority. Over the following eight weeks, Powell fine-tuned his opinion to secure the willingness of each group to join part of it. The other justices began work on opinions that would set forth their views.[70]

Decision

Justice Lewis F. Powell

The Supreme Court's decision in Bakke was announced on June 28, 1978. The justices penned six opinions; none of them, in full, had the support of a majority of the court. In a plurality opinion,[a] Justice Powell delivered the judgment of the court. Four justices (Burger, Stewart, Rehnquist, and Stevens) joined with him to strike down the minority admissions program and admit Bakke. The other four justices (Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun) dissented from that portion of the decision, but joined with Powell to find affirmative action permissible under some circumstances, though subject to an intermediate scrutiny standard of analysis. They also joined with Powell to reverse that portion of the judgment of the California Supreme Court that forbade the university to consider race in the admissions process.[71]

Powell's opinion

Justice Powell, after setting forth the facts of the case, discussed and found it unnecessary to decide whether Bakke had a private right of action under Title VI, assuming that was so for purposes of the case.[72] He then discussed the scope of Title VI, opining that it barred only those racial classifications forbidden by the Constitution.[73]

Turning to the program itself, Powell determined that it was not simply a goal, as the university had contended, but a racial qualification—assuming that UC Davis could find sixteen minimally qualified minority students, there were only 84 seats in the freshman class open to white students, whereas minorities could compete for any spot in the 100-member class. He traced the history of the jurisprudence under the Equal Protection Clause, and concluded that it protected all, not merely African Americans or only minorities. Only if it served a compelling interest could the government treat members of different races differently.[74]

Powell noted that the university, in its briefs, had cited decisions where there had been race-conscious remedies, such as in the school desegregation cases, but found them inapposite as there was no history of racial discrimination at the University of California-Davis Medical School to remedy. He cited precedent that when an individual was entirely foreclosed from opportunities or benefits provided by the government and enjoyed by those of a different background or race, this was a suspect classification. Such discrimination was only justifiable when necessary to a compelling governmental interest. He rejected assertions by the university that government had a compelling interest in boosting the number of minority doctors, and deemed too nebulous the argument that the special admissions program would help bring doctors to underserved parts of California—after all, that purpose would also be served by admitting white applicants interested in practicing in minority communities. Nevertheless, Powell opined that government had a compelling interest in a racially diverse student body.[75]

In a part of the opinion concurred in by Chief Justice Burger and his allies, Powell found that the program, with its set-aside of a specific number of seats for minorities, did discriminate against Bakke, as less restrictive programs, such as making race one of several factors in admission, would serve the same purpose. Powell offered the example (set out in an appendix) of the admissions program at Harvard University as one he believed would pass constitutional muster—that institution did not set rigid quotas for minorities, but actively recruited them and sought to include them as more than a token part of a racially and culturally diverse student body. Although a white student might still lose out to a minority with lesser academic qualifications, both white and minority students might gain from non-objective factors such as the ability to play sports or a musical instrument. Accordingly, there was no constitutional violation in using race as one of several factors.[76][77]

Powell opined that because the university had admitted that it could not prove that Bakke would not have been admitted even had there been no special admissions program, the portion of the California Supreme Court's decision ordering Bakke's admission was proper, and was upheld. Nevertheless, the state was entitled to consider race as one of several factors, and the portion of the California court's judgment which had ordered the contrary was overruled.[78]

Other opinions

Brennan delivered the joint statement of four justices: Marshall, White, Blackmun and himself. In verbally introducing their opinion in the Supreme Court courtroom, Brennan stated that the "central meaning" of the Bakke decision was that there was a majority of the court in favor of the continuation of affirmative action.[79] In the joint opinion, those four justices wrote, "government may take race into account when it acts not to demean or insult any racial group, but to remedy disadvantages cast on minorities by past racial prejudice".[80] They suggested that any admissions program with the intention of remedying past race discrimination would be constitutional, whether that involved adding bonus points for race, or setting aside a specific number of places for them.[81]

White issued an opinion expressing his view that there was not a private right of action under Title VI.[82][83] Thurgood Marshall also wrote separately, recounting at length the history of discrimination against African-Americans, and concluding, "I do not believe that anyone can truly look into America's past and still find that a remedy for the effects of that past is impermissible."[81][84] Blackmun subscribed to the idea of color consciousness, declaring that, "in order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race. There is no other way. And in order to treat some persons equally, we must treat them differently. We cannot—we dare not—let the Equal Protection Clause perpetuate racial superiority."[82][85]

Justice Stevens, joined by Burger, Stewart and Rehnquist, concurring in part and dissenting in part in the judgment, found it unnecessary to determine whether a racial preference was ever allowed under the Constitution. A narrow finding that the university had discriminated against Bakke, violating Title VI, was sufficient, and the court was correct to admit him.[86] "It is therefore perfectly clear that the question whether race can ever be used as a factor in an admissions decision is not an issue in this case, and that discussion of that issue is inappropriate."[87] According to Stevens, "[t]he meaning of the Title VI ban on exclusion is crystal clear: Race cannot be the basis of excluding anyone from a federally funded program".[88][89] He concluded, "I concur in the Court's judgment insofar as it affirms the judgment of the Supreme Court of California. To the extent that it purports to do anything else, I respectfully dissent."[90]

Reaction

Newspapers stressed different aspects of Bakke, often reflecting their political ideology. The conservative Chicago Sun-Times bannered Bakke's admission in its headline, while noting that the court had permitted affirmative action under some circumstances. The Washington Post, a liberal newspaper, began its headline in larger-than-normal type, "Affirmative Action Upheld" before going on to note that the court had admitted Bakke and curbed quotas.[91]The Wall Street Journal, in a headline, deemed Bakke "The Decision Everybody Won".[92] According to Oxford University Chair of Jurisprudence Ronald Dworkin, the court's decision "was received by the press and much of the public with great relief, as an act of judicial statesmanship that gave to each party in the national debate what it seemed to want most".[93]

Attorney General Griffin Bell, after speaking with President Jimmy Carter, stated, "my general view is that affirmative action has been enhanced", and that such programs in the federal government would continue as planned.[94]Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Chair Eleanor Holmes Norton told the media "that the Bakke case has not left me with any duty to instruct the EEOC staff to do anything different".[95]

Harvard Law School Professor Laurence Tribe wrote in 1979, "the Court thus upheld the kind of affirmative action plan used by most American colleges and universities, and disallowed only the unusually mechanical—some would say unusually candid, others would say unusually impolitic—approach taken by the Medical School" of UC Davis.[96]Robert M. O'Neil wrote in the California Law Review the same year that only rigid quotas were foreclosed to admissions officers and even "relatively subtle changes in the process by which applications were reviewed, or in the resulting minority representation, could well produce a different alignment [of justices]".[97] Law professor and future judge Robert Bork wrote in the pages of The Wall Street Journal that the justices who had voted to uphold affirmative action were "hard-core racists of reverse discrimination".[94]

Allan Bakke had given few interviews during the pendency of the case, and on the day it was decided, went to work as usual in Palo Alto.[56] He issued a statement through attorney Colvin expressing his pleasure in the result and that he planned to begin his medical studies that fall.[98] Most of the lawyers and university personnel who would have to deal with the aftermath of Bakke doubted the decision would change very much. The large majority of affirmative action programs at universities, unlike that of the UC Davis medical school, did not use rigid numerical quotas for minority admissions and could continue.[99] According to Bernard Schwartz in his account of Bakke, the Supreme Court's decision "permits admission officers to operate programs which grant racial preferences—provided that they do not do so as blatantly as was done under the sixteen-seat 'quota' provided at Davis".[100]

Aftermath

Allan Bakke, "America's best known freshman", enrolled at the UC Davis medical school on September 25, 1978.[101] Seemingly oblivious to the questions of the press and the shouts of protesters, he stated only "I am happy to be here" before entering to register.[101] When the university declined to pay his legal fees, Bakke went to court, and on January 15, 1980, was awarded $183,089.[98] Graduating from the UC Davis medical school in 1982 at age 42, he went on to a career as an anesthesiologist at the Mayo Clinic and at the Olmsted Medical Group in Rochester, Minnesota.[102][103]

In 1996, Californians by initiative banned the state's use of race as a factor to consider in public schools' admission policies.[104][b] The university's Board of Regents, led by Ward Connerly, voted to end race as a factor in admissions. The regents, to secure a diverse student body, implemented policies such as allowing the top 4% of students in California high schools guaranteed admission to the University of California System[106]—this, it was felt, would aid minority inner-city students.[107]

Dworkin warned in 1978 that "Powell's opinion suffers from fundamental weaknesses, and if the Court is to arrive at a coherent position, far more judicial work remains to be done than a relieved public yet realizes".[93] The Supreme Court has continued to grapple with the question of affirmative action in higher education. In the 2003 case of Grutter v. Bollinger, it reaffirmed Justice Powell's opinion in Bakke in a majority opinion, thus rendering moot concerns expressed by lower courts that Bakke might not be binding precedent due to the fractured lineup of justices in a plurality opinion.[108] The court's decision in the 2013 case of Fisher v. University of Texas made alterations to the standards by which courts must judge affirmative action programs, but continued to permit race to be taken into consideration in university admissions, while forbidding outright quotas.[109][110]

See also

- Civil Rights Movement

Notes and references

Notes:

^ Under Supreme Court precedent, a plurality opinion, for purposes of precedent, is to be "viewed as that position taken by those Members who concurred in the judgments on the narrowest grounds.” Marks v. United States, 430 U.S. 188, 193 (1977).

^ California's Proposition 209 mandates that "the state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting."[105]

References:

^ Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978). This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

^ Wilkinson, p. 79.

^ Wilkinson, p. 24.

^ Ball, p. 6.

^ ab Schwartz, pp. 28–29.

^ Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

^ Green, 391 U.S. at 441.

^ Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1970).

^ Ball, pp. 3–10.

^ ab Schwartz, p. 4.

^ Bakke, 238 U.S. at 272–275.

^ Bakke, 238 U.S. at 274.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 275.

^ abcd Ball, pp. 22–45.

^ DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 (1974).

^ DeFunis, 416 U.S. at 314–317.

^ DeFunis, 416 U.S. at 319–320.

^ DeFunis, 416 U.S. at 350.

^ Freedburg, Louis (June 27, 1998). "After 20 Years, Bakke Ruling Back in the Spotlight / Foes of college affirmative action want high court to overturn it". SF Gate. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcde O’Neill, Timothy J. Bakke and the Politics of Equality: Friends and Foes in the Classroom of Litigation. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. pp. 21–27. ISBN 978-0819561992.

^ abcdef Dreyfuss, Joel (1979). The Bakke Case: the Politics of Inequality. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 13, 16. ISBN 978-0156167826.

^ Thernstrom, Stephan; Thernstrom, Abigail (2009) [1999]. America in Black and White. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1439129098.

^ Lindsey, Robert (June 29, 1978). "Bakke: A man driven to become a doctor". The New York Times via Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 8.

^ Santa Clara Law Review, p. 231.

^ Schwartz, p. 5.

^ ab Bakke, 438 U.S. at 276.

^ Ball, p. 52.

^ Schulman, Bruce J. (2002). The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0306811265.

^ abcd Benfell, pp. 17, 52–54.

^ Schwartz, pp. 6–7.

^ Schwartz, pp. 7–8.

^ Schwartz, p. 8.

^ ab Bakke, 438 U.S. at 277.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 275–276.

^ Trombley, William (July 5, 1976). "Medical Dean Aids 'Special Interest' Applicants". Los Angeles Times. pp. C1, C4. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

(subscription required)

^ Nesbitt, Tim (October 1977). "Bakke passed over for white VIPs". The East Bay Voice. Berkeley, CA. pp. 1, 10.

^ abcde Complete Case Record, p. 7.

^ Ball, pp. 56–57.

^ ab Ball, p. 58.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 279.

^ Schwartz, pp. 18–19.

^ Schwartz, p. 19.

^ ab Ball, pp. 58–60.

^ Bakke v. Regents of the University of California, 18 Cal. 3d 34, 132 Cal. Rptr. 680, 553 P.2d 1152 (1976).

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 279–280.

^ Bakke, 18 Cal. 3d at 55.

^ Stevens, p. 24.

^ Bakke, 18 Cal. 3d at 90.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 280.

^ Bakke, 18 Cal. 3d at 64.

^ Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 429 U.S. 953 (1976) (Rehnquist, J., as circuit justice, granting stay).

^ ab Ball, p. 61.

^ Ball, pp. 64–67.

^ Epstein & Knight, pp. 346–347.

^ Ball, pp. 68–69.

^ ab Robert C. Barring, "Introduction to the Bakke case" in Complete Case Record at xxi–xxiv.

^ Ball, pp. 69–70.

^ Ball, pp. 76–83.

^ ab Ball, pp. 74–77.

^ "School drops attempt to bar white student". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. July 5, 1978. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

^ Schwartz, pp. 47–52.

^ Weaver Jr., Warren (October 13, 1977). "Justices hear Bakke arguments but give little hint on decision" (PDF). The New York Times. pp. A1, B12. Retrieved August 12, 2013.(registration required)

^ Schwartz, p. 48.

^ Epstein & Knight, pp. 347–349.

^ Ball, pp. 103–104.

^ Ball, pp. 105–106.

^ Ball, p. 107.

^ Schwartz, pp. 81–85.

^ Schwartz, pp. 98–107.

^ Schwartz, pp. 120–141.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 265–272.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 272–284.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 284–287.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 287–299.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 300–315.

^ Ball, pp. 137–139.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 300–320.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 320–321.

^ Schwartz, pp. 146–147.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 325.

^ ab Bakke, 438 U.S. at 378.

^ ab Ball, p. 140.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 387.

^ Ball, pp. 139–140.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 407.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 409–411.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 411.

^ "Excerpts from opinions by Supreme Court justices in the Allan P. Bakke case" (PDF). The New York Times. June 29, 1978. p. A20. Retrieved August 14, 2013.

(subscription required)

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 418.

^ Bakke, 438 U.S. at 421.

^ Ball, pp. 140–141.

^ Schwartz, pp. 151–152.

^ ab Ronald Dworkin, "The Bakke decision: did it decide anything?" in Complete Case Record at xxv–xxxiv.

^ ab Ball, p. 142.

^ Ball, pp. 142–143.

^ Tribe, p. 864.

^ O'Neil, p. 144.

^ ab Ball, p. 143.

^ Herbers, John (June 29, 1978). "A plateau for minorities" (PDF). The New York Times. pp. A1, A22. Retrieved August 15, 2013.(subscription required)

^ Schwartz, p. 153.

^ ab Kushman, Rick (September 27, 1978). "Bakke enters UC Davis Medical School". The California Aggie. Davis, California. pp. 1, 8.

^ Ball, p. 46.

^ Diamond, S.J. (August 30, 1992). "Where are they now? : A drifter, a deadbeat and an intensely private doctor". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

^ Egelko, Bob (February 14, 2012). "U.S. appeals court hears challenge to Prop. 209". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

^ "Text of Proposition 209". California Secretary of State. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2013.

^ Ball, p. 164.

^ "California governor touts 4 percent solution". AP via Bangor Daily News. January 6, 1999. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

^ Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003).

^ Liptak, Adam (June 25, 2013). "Justices step up scrutiny of race in college entry". The New York Times. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

^ Fisher v. University of Texas, 133 S. Ct. 2411 (2013).

Bibliography

Ball, Howard (2000). The Bakke Case: Race, Education, and Affirmative Action. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-070061046-4.

Benfell, Carol (Fall 1977). "Should the Constitution really be colorblind?". Barrister. American Bar Association, Young Lawyers Section. 3 (4): 17, 52–54.

Epstein, Lee; Knight, Jack (2001). "Piercing the Veil: William J. Brennan's Account of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke". Yale Law & Policy Review. New Haven, CT: Yale Law & Policy Review, Inc. 19 (2): 341–379. JSTOR 40239568.

O'Neil, Robert M. (January 1979). "Bakke in balance: some preliminary thoughts". California Law Review. Berkeley, CA: California Law Review, Inc. 67 (1): 143–170. doi:10.2307/3480092. JSTOR 3480092.

Regents of the University of California v. Allan Bakke Complete Case Record. 1. Englewood, CO: Information Handling Services. 1978. ISBN 0-910972-91-5.

"Review of The Bakke Case: Race, Education, and Affirmative Action". Santa Clara Law Review. Santa Clara, CA: Santa Clara Law Digital Commons.

Schwartz, Bernard (1988). Behind Bakke: Affirmative Action and the Supreme Court. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-7878-X..

Stevens, John M. (September 1977). "The good news of Bakke". The Phi Delta Kappan. Arlington, VA: Phi Delta Kappa International. 59 (1): 23–26. JSTOR 20298825.

Tribe, Laurence H. (February 1979). "Perspectives on Bakke: equal protection, procedural fairness, or structural justice?". Harvard Law Review. Cambridge, MA: The Harvard Law Review Association. 92 (4): 864–877. doi:10.2307/1340556. JSTOR 1340556.

Wilkinson III, J. Harvie (1979). From Brown to Bakke. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502897-X.

External links

- Text of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978) is available from: CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)

Regents of Univ. Cal v. Bakke from C-SPAN's Landmark Cases: Historic Supreme Court Decisions