Court of Requests

The Court of Requests was a minor equity court in England and Wales. The court was instituted by King Richard III in his 1484 Parliament. It first became a formal tribunal with some Privy Council elements under Henry VII, hearing cases from the poor and the servants of the King. It quickly became popular on account of the low cost of bringing a case and the rapid processing time, earning the disapproval of the common law judges. Two formal judges, the "Masters of Requests Ordinary", were appointed towards the end of Henry VIII's reign, with an additional two "Masters of Requests Extraordinary" appointed under Elizabeth I to allow two judges to accompany her on her travels around England. Two more Ordinary Masters were appointed under James I of England, with the increasing volume of cases bringing a wave of complaints as the Court's business and backlog grew.

The Court became embroiled in a dispute with the common law courts during the late 16th century, who were angry at the amount of business deserting them for the Court of Requests. During the 1590s they went on the offensive, overwriting many decisions made by the Requests and preventing them imprisoning anyone. It is commonly accepted that this was a death-blow for the Court, which, dependent on the Privy Seal for authority, died when the English Civil War made the Seal invalid.

Contents

1 History

2 Other Courts of Requests

3 See also

4 References

5 Bibliography

History

The precise origins of the Court of Requests are unknown. Spence traces it back to the reign of Richard II,[1]Leadam claims there is no record of the Court's existence before 1493,[2]Pollard writes (based on documents discovered after Leadam's work) that it was in existence from at least 1465,[3] while Alexander writes that it first appeared during the reign of the House of York,[4] and Kleineke states that it was created in 1485 by Richard III.[5] Whatever its origin, the Court was created as part of the Privy Council, following an order by the Lord Privy Seal that complaints and cases brought to the Council by the poor should be expedited.[6] This was as part of the Privy Council; it first became an independent tribunal with some Privy Council elements under Henry VII, with jurisdiction mainly over matters of equity. The Court became increasingly popular due to the lack of cost in bringing a case to it and the speed at which it processed them, in contrast with the slow and expensive common law courts, arousing the ire of common law lawyers and judges.[7]

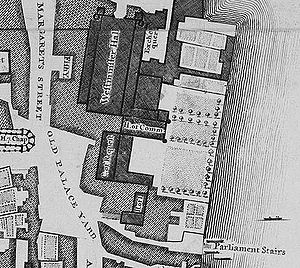

The Old Palace of Westminster showing where the Court of Requests met

The court originally followed the Monarch on his trips around England, visiting Sheen, Langley and Woodstock in 1494. Under Thomas Wolsey the Court became fixed in Westminster, hearing cases from poor people and from the servants of the King.[8] It met at the White Hall of the Palace of Westminster and is often called the Court of White Hall. Towards the end of Henry VIII's reign, the Court took on a professional attitude with the appointment of two professional "Masters of Requests Ordinary" to act as judges, rather than simply the Lord Privy Seal as was previously the case. An additional two "Masters of Requests Extraordinary" appointed under Elizabeth I to allow two judges to accompany her on her travels around England. Under James I of England, two more Ordinary Masters were appointed, but despite this the Court became criticised for the rising backlog due to its increasing business.[9]

When the Court formally became an independent body in the 16th century, free of Privy Council control, it immediately became vulnerable to attack by the common-law courts, which asserted that it had no formal jurisdiction and that the Court of Chancery was an appropriate equitable body for cases. It was technically true that the Court, as it was no longer part of the Privy Council, could not claim jurisdiction based on tradition, but in 1597 Sir Julius Caesar (then a Master of Requests Ordinary) gave examples of times when the common law courts had recognised the Court of Requests' jurisdiction as recently as 1585.[10] The common law courts change of heart was undoubtedly due to the large amount of business deserting them for the Court of Requests, and in 1590 they went on the offensive; writs of habeas corpus were issued for people imprisoned for contempt of court in the Requests, judgments were issued in cases the Court of Requests were dealing with and it was decided that jailing an individual based on a writ from the Court of Requests constituted false imprisonment.[11] Most academics accept that the Court never recovered from these blows, and when the English Civil War made the Privy Seal inoperative, the Court "died a natural death".[12] The post of Master of Requests was abolished in 1685.

Other Courts of Requests

Another Court of Requests was by act of the Common Council of the City of London on February 1, 1518. It had jurisdiction over small debts under 40 shillings between citizens and tradesmen of the City of London. The judges of the court were two aldermen and four ancient discreet commoners. It was also called the Court of Conscience in the Guild Hall where it met. Under James I Acts of Parliament were passed regulating its procedure 1 James I ch.14 and 3 James I ch. 15. These were the first Acts of Parliament that gave validity to a Court of Requests.[13]

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth century small claims court were established in various parts of England called The Court of Requests. The first of these was found in Southwark by 22 George II ch.47.[14] They were abolished by the County Court Act 1846.

See also

List of Masters of Requests – Chronological list of Masters of Requests

References

^ Spence (1846) p. 350

^ Leadam (1898) p. x

^ Pollard (1941) p. 301

^ Alexander (1981) p. 67

^ Kleineke (2007), pp. 22–32

^ Carter (1962) p. 162

^ Alexander (1981) p. 68

^ Carter (1962) p. 163

^ Carter (1962) p. 164

^ Carter (1962) p. 165

^ Carter (1962) p. 166

^ Carter (1962) p. 167

^ Leadam (1898) pp. liii–liv

^ Leadam (1898) p. liv

Bibliography

Alexander, Michael (1981). The first of the Tudors: a study of Henry VII and his reign. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-7099-0503-3..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Carter, Albert Thomas (1910). A History of English Legal Institutions. Butterworth. OCLC 60732892.

Kleineke, Hannes (2007). "Richard III and the Origins of the Court of Requests". The Ricardian. XVII.

Leadam, Isaac Saunders (1898). Selected Cases in the Court of Requests. The Selden Society.

Pollard, Albert Fredrick (1941). "The Growth of the Court of Requests". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 56 (222): 300–303. doi:10.1093/ehr/lvi.ccxxii.300. ISSN 0013-8266.

Spence, George (1846). The Equitably Jurisdiction of the Court of Chancery. Lea and Blanchard.