Smalls Paradise

| |

Smalls Paradise. Founder Ed Smalls is seen at upper right. | |

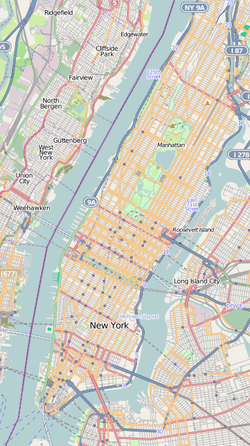

Smalls Paradise Location in New York City | |

| Address | 2294 7th Avenue New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°48′55″N 73°56′39″W / 40.81528°N 73.94417°W / 40.81528; -73.94417Coordinates: 40°48′55″N 73°56′39″W / 40.81528°N 73.94417°W / 40.81528; -73.94417 |

| Owner | Ed Smalls |

| Opened | 1925 (1925) |

| Closed | 1980s |

Smalls Paradise (often called Small's Paradise and Smalls' Paradise, and not to be confused with Smalls Jazz Club), was a nightclub in Harlem, New York City. Located in the basement of 2294 Seventh Avenue, it opened in 1925 and was owned by Ed Smalls. At the time of the Harlem Renaissance, Smalls Paradise was the only one of the well-known Harlem night clubs to be owned by an African-American and integrated. Other major Harlem night clubs admitted only white patrons unless the person was an African-American celebrity.

The entertainment at Smalls Paradise was not limited to the stage; waiters danced the Charleston or roller-skated as they delivered orders to customers. Waiters were also known to vocalize during the club's floor shows. Unlike most of the Harlem clubs which closed between 3 and 4 am, Smalls was open all night, offering a breakfast dance which featured a full floor show beginning at 6 am.

After 30 years as the owner of the night club, Ed Smalls sold the club to Tommy Smalls (no relation) in 1955. It was later owned by Harlem businessman Pete McDougal and Wilt Chamberlain, and renamed Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise. Many well known musicians, both white and African-American, appeared at the club over the years and often came to Smalls after their evening engagements to jam with the Smalls Paradise band. The club was responsible for promoting popular dances such as the Charleston, the Madison and the Twist. Smalls Paradise was the longest-operating club in Harlem before it closed in 1986. The building has been the site of Thurgood Marshall Academy since 2004.

Contents

1 Early history

2 New ownership

2.1 Tommy Smalls

2.2 Wilt Chamberlain

3 Dances renew popularity

4 After the Twist

5 Last dance

6 In popular culture

7 Albums recorded at Smalls Paradise

8 Notes

9 References

10 Sources

Early history

Entrepreneur Ed Smalls[a] owned a small venue in Harlem, the Sugar Cane Club, from 1917 to 1925, which catered primarily to local residents.[4][5] When Smalls opened Smalls Paradise [b] in the basement of an office building at 2294 Seventh Avenue, he envisioned a night club which would not exclude his neighbors but would also be attractive to New Yorkers who lived in the city's downtown area.[2][4][9] Smalls arranged a lavish gala for the club's opening on October 26, 1925, which was attended by almost 1,500 people. Though Prohibition was in effect, patrons were able to bring their own liquor or purchase bootlegged liquor from the club's waiters.[4]

Opening Day music was provided by Charlie Johnson and his musicians, who remained as the "house band" for ten years.[4][10] The members of Johnson's band included Jabbo Smith, Benny Carter, Jimmy Harrison, Sidney De Paris and Sidney Bechet.[11] While performing at Smalls Paradise in 1925, Sam Wooding and his orchestra were heard by a Russian impresario; Leonidoff promptly hired Wooding and his musicians for a European tour with the Chocolate Kiddies revue. The revue opened in Berlin in 1925, with Wooding and his band performing in the revue for a year. Wooding and his orchestra left the revue to perform in Europe and South America until 1927.[12][13][14]

Banjo player Elmer Snowden, whose band played at the Smalls Paradise Sunday matinees, would often jam with the Johnson band after he had finished his nightly performance at the Hot Feet Club.[15] Other musicians also made it a habit to drop in at Smalls Paradise after their engagements were over for the evening. Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey and Buddy Rich often came to Smalls Paradise to jam with the house band for the joy of it.[16][17]

Ed Smalls in 1931

Like the other large and successful night clubs in Harlem, the Cotton Club and Connie's Inn, Smalls regularly showcased revues which featured the club's permanent staff of entertainers.[5] Ed Smalls commissioned original music for the stage productions of the night club.[18] Smalls Paradise was the only major Harlem night spot which was owned by an African-American and was racially integrated.[5][19][18][c] The other clubs admitted only white patrons unless the person was an African-American celebrity.[4] Smalls previously had some success in attracting a racially mixed clientele at his Sugar Cane Club with the quality entertainment and waiters who danced while balancing trays of drinks and sang during floor shows.[5] Beginning with the opening of Smalls Paradise, Smalls had his waiters dance the Charleston while serving guests; patrons were also served drinks by waiters on roller skates.[5][21][22]

Smalls Paradise had no cover charge and stayed open longer than most of the others, including the Cotton Club.[2][21] At Smalls Paradise, patrons could also reserve a seat at the club by paying a yearly fee. Many regular visitors of Harlem's night clubs also found the food better at Smalls Paradise than at either The Cotton Club or Connie's Inn.[18] While most of the night spots shut their doors between 3 and 4 am, Smalls Paradise began breakfast dances at 6 am with a floor show of up to 30 dancers and a full jazz band.[21]

Smalls Paradise celebrated its fourth anniversary in 1929 and by 1930, it began an arrangement with WMCA Radio to have twice weekly broadcasts from the club.[7][23] During Ed Small's ownership of the club, he organized many gala charity events which were held at Smalls Paradise with the proceeds donated to help the needy of the Harlem community. One memorable gala in 1931 featured Bill "Bojangles" Robinson. Entertainers from both the Cotton Club and Connie's Inn made appearances at the event with the permission of the clubs' management.[24][d] Ed Smalls was doing well enough at the time of the club's tenth year in business to greatly expand the Smalls Paradise floor space by moving the club's bar upstairs.[26] Smalls continued to expand the club on street level, opening his Orchid Room in 1942.[27]

Smalls Paradise circa 1942. Upper left: the Clover Bar moved upstairs in 1936, Upper right:the Orchid Room, opened circa 1942 Bottom: front of the club and the marquee.

In the early 1930s, a female singer with Charlie Johnson's band arranged an audition with the band for a young hopeful at Smalls Paradise. When the girl was asked what key she sang in, she replied that she did not know, and the audition was unsuccessful. This was Billie Holiday's first try as a professional singer.[28][22] Jazz musician Fats Waller was a frequent visitor to Smalls Paradise. With a new Victor recording contract in 1934, Waller was in need of sidemen to record with. Playing in the house band at Smalls Paradise were Harry Dial and Herman Autrey; both were recruited by Waller at Smalls Paradise and recorded with him as Fats Waller and His Rhythm.[29][30]

A young Malcolm X, who enjoyed the atmosphere at Smalls Paradise, worked there as a waiter between 1942 and 1943.[31] Civil rights activist Doctor W. E. B. Du Bois celebrated his 83rd birthday at Smalls Paradise on February 23, 1951. The banquet, sponsored by Albert Einstein, Mary McLeod Bethune, Paul Robeson and others, was originally to be held at New York's Essex House. This was during the era of McCarthyism; a pro-McCarthy group circulated a newsletter labeling Du Bois, Einstein and others connected with the dinner as being pro-Communist. When the Essex House canceled the banquet, it was held at Smalls Paradise.[32]

New ownership

Tommy Smalls

Tommy Smalls and fan club members in 1956

Founder and long-time owner Ed Smalls sold the club to popular disc jockey Tommy Smalls in late 1955.[33] Smalls, known as "Dr. Jive", was an early enthusiast of rock 'n' roll. Like his contemporary, Alan Freed, Smalls also organized rock 'n' roll shows held at New York area theaters.[34][35] He held a grand opening gala at the club on December 13, 1955, which was attended by many prominent people in the music industry. A special guest was baseball star Willie Mays.[36] He began broadcasting his WWRL radio program from the club shortly after his ownership.[37][e]

Wilt Chamberlain

Chamberlain at the club in 1961

By the late 1950s, Smalls Paradise was in trouble as it had lost substantial business. Basketball star Wilt Chamberlain, who had always wanted to own a night club; was able to purchase Smalls Paradise with a business partner Pete McDougall in 1961.[40][41] After purchasing the club, Chamberlain spent up to 18 hours a day at Smalls Paradise, as a celebrity host and learning the night club business.[40] He renamed the venue Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise and changed the club's style of music from jazz to rhythm and blues for economic reasons. One of the first performers at Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise was Ray Charles.[42][43] Chamberlain also began booking African-American comedians; Redd Foxx played at Big Wilt's in December 1961.[44] Smalls Paradise had been a place for African-American baseball players to gather during the time it was owned by Tommy Smalls.[45] Under Chamberlain's ownership, it now became a place where African American basketball players would meet.[46]

A number of white jazz musicians regularly performed at the club alongside blacks. Jazz guitarist Pat Martino recalls that he began playing at the club as a teenager (in the late 1950s), and would often play until 4 am in the morning. After the clubs closed he would then join guitarists such as Wes Montgomery and Grant Green for breakfast.[47]

Dances renew popularity

Smalls Paradise played a role in popularizing the Madison in 1960, but the night club's burst of popularity in the early 1960s came from the later dance craze, the Twist.[48][49] Since Tuesday nights were exceptionally slow at Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise, the club looked for a way to bring in more business. Someone came up with the idea to hold Twist dance contests on Tuesday evenings and the club's weekly contest started in December 1961.[50] A hostess for the Paris night club, the Blue Note, visited Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise shortly after the contest began; she was there to learn the Twist and take the dance back to the Paris club,[51]

Comedians Jackie "Moms" Mabley and Slappy White doing the Twist at Smalls Paradise in 1962

By the beginning of 1962, BBC-TV came with a crew to film the twisting at the night spot for broadcast in the UK and journalists from many foreign newspapers visited to take photos and file news stories. Delegates from the United Nations had also found their way to the night club for the Tuesday night contest.[50] Those participating in the contest were patrons of Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise. The only dance professionals doing the twist at the club were Mama Lou Parks and the Parkettes, who were there to provide lessons to novices.[50][52] The Tuesday night twist contest brought patrons in limousines from downtown just as the entertainment at Smalls Paradise had done years before.[50][53][9] As King Curtis played, Chamberlain was greeting royalty, as well as various show business and political figures.[54][50] Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise saw over 250,000 guests in the year since its weekly Twist contest began.[9] The club was continually at capacity on Tuesday evenings until it closed at 4 am. Many people had to be turned away each week because they did not have the necessary reservations.[53]

When author James Baldwin's 1962 novel Another Country appeared in print, his publisher held a twist party for him at Baldwin's favorite night club, Smalls Paradise. The guest list included many of Baldwin's friends as well as literary figures.[9][55] Despite the fact that many in-town celebrities were also invited, some of those who were not on the guest list crashed the party.[56]

After the Twist

In 1968, a group of Tuskegee University students arrived in New York hoping to make a musical impression. They auditioned at Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise but were turned down by one of the owners who believed the music genre funk was on the way out. A few days later, the group received a call from Big Wilt's, asking if they would be able to fill in for a last-minute performance cancellation at the club. Even though this was to be a one-night performance, the Commodores agreed to play at Big Wilt's.[57] The engagement was extended substantially, with the group winning praise from the club's talent manager, along with an invitation to play at Big Wilt's anytime.[58][59]

Singer Millie Jackson, a guest at Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise, began heckling a female vocalist onstage. When the vocalist challenged Jackson by asking her to do better. Jackson accepted the dare by singing Don't Play It No More. This was Jackson's first public appearance as a singer; she was hired for an engagement within two weeks of stepping onto the stage at Smalls.[60]

By the early 1970s, it was necessary to revamp Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise once more. Some of the club's patrons were using the night spot for illicit activities, such as drug dealing. The night club was cleared of those engaging in undesirable activities. Changes in the entertainment policy brought in acts like Jerry Butler and The Dells and the Vilmac Room was built for those who preferred to dance to a disco beat.[61][62]

Last dance

The former site of Smalls Paradise; Thurgood Marshall Academy in 2014.

By 1983, the club was known as the New Smalls Paradise. This version of Smalls Paradise offered everything from music and dancing to craft shows and political speeches.[63] By 1986, the club, which was the longest-operating night club in Harlem, had fallen vacant. Before its closure it had undergone a transition from a jazz to a disco club.[64][21] Just prior to the club's demise, the New York Swing Dance Society brought the Lindy Hop back to the dance floor at Smalls.[65]

The structure was purchased by the Abyssinian Development Corporation. The nonprofit corporation, affiliated with the Abyssinian Baptist Church, planned to completely renovate the building and add three floors to it. Further plans for the building were to lease the structure for 50 years to the New York Board of Education to house its Thurgood Marshall Academy and to lease space for an International House of Pancakes restaurant.[66] The school opened in 2004; all traces of Smalls Paradise were wiped out with the renovation.[64][67]

In popular culture

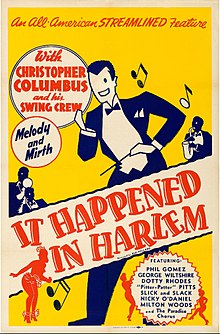

It Happened in Harlem poster

Photographer and writer Carl Van Vechten was a frequent patron of Harlem's night clubs for some years. Van Vechten had been a guest at Ed Smalls' Sugar Cane Club as well as at Smalls Paradise.[68] Van Vechten's 1926 novel, Nigger Heaven, was based on some of his observations of Harlem's night life; he referred to Smalls Paradise as The Black Venus in the novel.[1] After the book was published, Smalls' employees were offended enough by Van Vechten's portrayal of Harlem to bar Van Vechten from the night club permanently.[21]

In 1932, Elmer Snowden with his Smalls Paradise band and some of the club's entertainers, were hired by Warner Brothers to star in a film short called Smash Your Baggage.[69] The entire group was credited as "Smalls Paradise Entertainers" and not by individual names.[70][71] The film's plot involved a group of Pullman porters who decided to hold a benefit for one of their own.[72][73] The ten-minute film was shot at the Atlantic Avenue station of the Long Island Rail Road and it is the only recording of these musicians playing together; this group produced no records together.[74][71]

Smalls Paradise was the subject of a 1945 film, It Happened in Harlem, produced by All American News. The plot revolves around Ed Smalls' singer drawing record crowds at Smalls Paradise until the singer receives his draft notice. Smalls begins auditions to try to replace his star vocalist. A little-known young man with a following tries to audition for Smalls, but is turned away. One of the young man's ardent fans then persuades Smalls to give him an audition.[75] Actor George Wiltshire plays the role of Ed Smalls.[76]

Albums recorded at Smalls Paradise

Groovin' at Smalls' Paradise Jimmy Smith 1957[77]

Cool Blues Jimmy Smith 1958[78]

Live At Small's Paradise Babs Gonzales 1953[79]

Live at Small's Paradise King Curtis 1966[80]

Notes

^ Smalls, a former elevator operator from Charleston, South Carolina, was the grandson of Civil War hero and U. S. Congressman Robert Smalls.[1][2] Smalls died at the age of 92 on October 13, 1974.[3]

^ A photo of the original marquee shows no apostrophe.[6] Other material, such as this postcard produced to promote the club and a news story, show other variations.[7][8]

^ The Cotton Club was owned by New York gangster Owney Madden after 1923 and Connie's Inn was owned by George and Connie Immerman.[20]

^ Smalls Paradise two major competitors, the Cotton Club and Connie's Inn, both closed in 1933.[25]

^ Both Smalls and Freed were later arrested and charged in connection with the 1959 payola scandal. Smalls was dismissed from WWRL following his arrest.[38] He later went to work for Polydor Records. Smalls died at the age of 45 in 1972.[39]

References

^ ab "Ed Smalls Dies at 92; Owned Famous Harlem Nightspot". Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing Company: 30. November 7, 1974. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved March 7, 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc Gill 2011, p. 271.

^ Fraser, C. Gerald (October 18, 1974). "Ed Smalls, Whose Club Brought the Famous to Harlem, Is Dead". New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ abcde Wintz & Finkelman 2004, p. 1120.

^ abcde Malone 1996, p. 86.

^ "Smalls Paradise, Harlem 1925". Harlem World Magazine. January 6, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ ab "Smalls Paradise to Observe 4th Anniversary". The New York Age. October 19, 1929. p. 7. Retrieved February 1, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

^ "Back of Postcard used to promote the night club circa 1940". Eagle Post Card View Company. c. 1940. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016.CS1 maint: Unfit url (link)

^ abcd Williams 2016.

^ Kirschner 2005, p. 271.

^ Kirschner 2005, pp. 154-155.

^ "Sam Wooding and His Orchestra". Red Hot Jazz. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

^ Williams 2002, pp. 66-67.

^ Feather & Gitler 1999, pp. 706-707.

^ Dance 2001, pp. 58-59.

^ Deffaa 1992, p. 42.

^ Matloff, Judith (April 7, 2002). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: HARLEM; For a Onetime Jazz Palace, Nostalgia and Controversy". New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

^ abc Ogren 1992, p. 74.

^ Gill 2011, p. 271, 323.

^ Wintz & Finkelman 2004, p. 910.

^ abcde Wintz & Finkelman 2004, p. 1121.

^ ab Clarke 2009, p. 67.

^ "New Revue at Smalls Paradise Next Week". The New York Age. September 20, 1930. p. 6. Retrieved February 1, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

^ "Smalls Cabaret Party For Unemployment Meets With Wonderful Success". The New York Age. March 21, 1931. p. 1. Retrieved February 1, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

^ Cullen 2007, p. 263.

^ "Ed Smalls Paradise Enlarges Floorspace and Opens New Bar". The New York Age. December 5, 1936. p. 9. Retrieved February 1, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

^ Warner, Wally (February 20, 1943). "Harlem Night Life". The New York Age. p. 10. Retrieved February 1, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

^ Kirschner 2005, p. 246.

^ Shipton 2010, pp. 76-77.

^ Jasen & Jones 2013, p. 401.

^ Gill 2011, p. 337.

^ Jerome & Taylor 2005, pp. 159-160.

^ "Izzy Rowe's Notebook". The Pittsburgh Courier. November 16, 1966. p. 24. Retrieved February 1, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

^ "Alan Freed Biography". Rock Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ TV Radio Mirror 1956, p. 14.

^ Hinckley, David (November 1, 2005). "Swept Away. Dr. Jive". New York Daily News. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ "Bill Davis Returns to Smalls' Home". The New York Age. December 17, 1955. p. 9. Retrieved February 1, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

^ "Disc Jockey Roundup". Alexandria Times-Tribune. May 25, 1960. p. 1. Retrieved February 1, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

^ "Record Promoter Tommy Smalls Dies of Illness in New York". Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing Company: 56. 1972-03-23. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ ab Robinson 1964, pp. 62-64.

^ "New York Beat". Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing Company: 63. March 9, 1961. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ Gill 2011, p. 395.

^ "New York Beat". Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing Company: 63. August 24, 1961. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ Pomerantz 2010, p. 17.

^ White 2011.

^ Pomerantz 2010, pp. 18-19.

^ "Here and Now". J.W. Pepper. Accessed via YouTube. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

^ Time magazine 1960.

^ Hughes 2002, p. 442.

^ abcde "Socialite Trade Returns to Harlem on Wings of Twist". Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing Company: 59–60. April 12, 1962. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ "New York Beat". Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing Company: 64. December 28, 1961. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ Selvin, Johnson & Cami 2012, p. 128.

^ ab Ebony 1962, pp. 38-42.

^ Selvin, Johnson & Cami 2012, pp. 127-128.

^ Leeming 2015.

^ Eckman 2014, pp. 165-166.

^ Thompson 2001, p. 112.

^ Lucas 1977, p. 61.

^ "New York Beat". Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing Company: 62. September 12, 1968. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ "New York Beat". Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing Company: 62. April 5, 1973. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ "New York Beat". Jet Magazine. Johnson Publishing Company: 62. August 30, 1973. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ Page, Tim (September 8, 1983). "Going Out Guide". New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ ab Gill, John Freeman (April 3, 2005). "Goodbye to All That". New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ Chevigny 2005, p. 53.

^ "Postings: Former Smalls' Paradise in Harlem; Nightclub Site To Riff Into A School". New York Times. August 26, 2001. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ Feuer, Alan (February 2, 2004). "Stress of Harlem's Rebirth Shows in School's Move to a New Building". New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ Shaw 1989, p. 60.

^ Chilton 1985, p. 314.

^ "Smash Your Baggage cast". IMDB. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ ab Yanow 2004, p. 314.

^ Baliett 2006, p. 195.

^ "Smash Your Baggage". IMDB. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ New York Media, LLC (August 31, 1995). "Museums, Societies, etc". New York Magazine: 59. ISSN 0028-7369. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

^ Richards 2005, pp. 90-91.

^ "It Happened in Harlem". IMDB. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ "Groovin' at Smalls' Paradise". Blue Note Discography. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ "Cool Blues". Blue Note Discography. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ "Live At Small's Paradise". Discogs. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

^ "Live at Small's Paradise". AllMusic. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

Sources

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Baliett, Whitney (2006). American Musicians II: Seventy-One Portraits in Jazz. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-5780-6834-0.

Bogdonav, Vladimir (2003). All Music Guide to Soul: The Definitive Guide to R&B and Soul. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8793-0744-8.

Chilton, John (1985). Who's who of Jazz: Storyville to Swing Street. Da Capo Press.

Chevigny, Paul (2005). Gigs: Jazz and the Cabaret Laws in New York City. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4153-4700-6 – via Questia.

Clarke, Donald (2009). Billie Holiday: Wishing on the Moon. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-7867-3087-2.

Cullen, Frank (2007). Vaudeville old & new: an encyclopedia of variety performances in America, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-4159-3853-2.

Dance, Stanley (2001). The World of Swing. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-3068-1016-9.

Deffaa, Chip (1992). Voices of the Jazz Age: Profiles of Eight Vintage Jazzmen. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-2520-6258-2.

Ebony (June 1962). "Twist is Universal Mania". Ebony Magazine. ISSN 0012-9011.

Eckman, Fern Marja (2014). The Furious Passage of James Baldwin. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5907-7321-5.

Feather, Leonard; Gitler, Ira (1999). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1998-8640-1 – via Questia.

Gill, Jonathan (2011). Harlem: The Four Hundred Year History from Dutch Village to Capital of Black America. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8021-9594-4.

Hughes, Langston (2002). The Collected Works of Langston Hughes: Essays on art, race, politics, and world affairs. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1394-5.

Jasen, David A.; Jones, Gene (2013). Spreadin' Rhythm Around: Black Popular Songwriters, 1880-1930. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-1355-0972-9.

Jerome, Fred; Taylor, Rodger (2005). Einstein on Race and Racism. Rutgers University press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4098-6 – via Questia.

Kirschner, Bill (2005). The Oxford Companion to Jazz. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-1951-8359-7.

Leeming, David (2015). James Baldwin: A Biography. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-6287-2469-1.}

Lucas, Bob (May 26, 1977). "Commodores Celebrate Success". Jet Magazine. ISSN 0021-5996.

Malone, Jacqui (1996). Steppin' on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-2520-6508-8.

Ogren, Kathy J. (1992). The Jazz Revolution: Twenties America & the Meaning of Jazz. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195074796 – via Questia.

Pomerantz, Gary M. (2010). Wilt, 1962: The Night of 100 Points and the Dawn of a New Era. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 978-0-3075-4938-9.

Richards, Larry (2005). African American Films Through 1959: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Filmography. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2274-6.

Robinson, Louie (August 1964). "Big Man, Big Business". Ebony Magazine. ISSN 0012-9011.

Selvin, Joel; Johnson, John, Jr.; Cami, Dick (2012). Peppermint Twist: The Mob, the Music, and the Most Famous Dance Club of the '60s. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-2500-1353-8.

Shaw, Arnold (1989). The Jazz Age: Popular Music in the 1920's. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1950-6082-9.

Shipton, Ayln (2010). Fats Waller. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-6780-4.

Thompson, Dave (2001). Funk. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8793-0629-8.

Time magazine (April 4, 1960). "The Jukebox: The Newest Shuffle". Time.

TV Radio Mirror (September 1956). "Dr. Jive". Macfadden Publishing.

White, Bill (2011). Uppity: My Untold Story About The Games People Play. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-4465-6418-2.

Williams, Iain Cameron (2002). Underneath a Harlem Moon. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-8264-5893-3.

Williams, John A. (2016). Flashbacks: A Twenty-Year Diary of Article Writing. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1-5040-3303-9.

Wintz, Gary D.; Finkelman, Paul (2004). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance, Volume 2 K-Y. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-5795-8458-0.

Yanow, Scott (2004). Jazz on Film: The Complete Story of the Musicians and Music Onscreen. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-6177-4701-4.