Pompeii

Aerial view of Pompeii | |

Shown within Italy | |

| Location | Pompei, Province of Naples, Campania, Italy |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°45′0″N 14°29′10″E / 40.75000°N 14.48611°E / 40.75000; 14.48611Coordinates: 40°45′0″N 14°29′10″E / 40.75000°N 14.48611°E / 40.75000; 14.48611 |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 64 to 67 ha (170 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | 6th–7th century BC |

| Abandoned | AD 79 |

| Site notes | |

| Website | www.pompeiisites.org |

UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | Archaeological Areas of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Torre Annunziata |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1997 (21st session) |

| Reference no. | 829 |

| Region | Europe |

Pompeii (/pɒmˈpeɪi/) was an ancient Roman city near modern Naples in the Campania region of Italy, in the territory of the comune of Pompei. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was buried under 4 to 6 m (13 to 20 ft) of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. Volcanic ash typically buried inhabitants who did not escape the lethal effects of the earthquake and eruption.

Largely preserved under the ash, the excavated city offers a unique snapshot of Roman life, frozen at the moment it was buried[1] and providing an extraordinarily detailed insight into the everyday life of its inhabitants. Organic remains, including wooden objects and human bodies, were entombed in the ash and decayed away, making natural molds; and excavators used these to make plaster casts, unique and often gruesome figures from the last minutes of the catastrophe. The numerous graffiti carved on the walls and inside rooms provides a wealth of examples of the largely lost Vulgar Latin spoken colloquially, contrasting with the formal language of the classical writers.

Pompeii is a UNESCO World Heritage Site status and is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Italy, with approximately 2.5 million visitors every year.[2]

Excavations recommenced in several unexplored areas of the city, and in 2018 new discoveries were reported.[3][4][5][6]

Contents

1 Name

2 Geography

3 History

3.1 Early history

3.2 The Samnite period

3.3 The Roman Period

3.3.1 AD 62–79

3.4 Eruption of Vesuvius

3.5 Rediscovery

4 Roman city development

5 Tourism

6 Conservation

6.1 House of the Gladiators collapse

7 In popular culture

8 Documentaries

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Name

Pompeii (pronounced [pɔmˈpɛjjiː]) in Latin is a second declension plural noun (Pompeiī, -ōrum). According to Theodor Kraus, "The root of the word Pompeii would appear to be the Oscan word for the number five, pompe, which suggests that either the community consisted of five hamlets or perhaps it was settled by a family group (gens Pompeia)."[7]

Geography

View from Porta Marina showing cliffs on city edge and Suburban Baths

The ruins of Pompeii are located near the modern town of Pompei and about 8 km (5.0 mi) away from Mount Vesuvius. It stands on a spur about 40 m above sea level formed by an ancient lava flow to the north of the mouth of the Sarno River (known in ancient times as the Sarnus). Three sheets of sediment from large landslides lie on top of the lava, perhaps triggered by extended rainfall.[8]

Today, Pompeii is some distance inland, but in ancient times it overlooked the coast and had a port. It covered a total of 64 to 67 hectares (170 acres) and was home to 11,000 to 11,500 people, on the basis of household counts.[9]

History

Early history

Settlement phases of Pompeii

red: 1st (Samnite) town

blue: 1st expansion

green: 2nd expansion

yellow: Roman expansion

The first stable settlements on the site date back to the 8th century BC when the Oscans,[10] a people of central Italy, founded five villages in the area.

With the arrival of the Greeks in Campania from around 740 BC Pompeii entered into the orbit of the Hellenic people and the most important building of this period is the Doric Temple, built not near the centre, but in a more isolated position in what would later become the Triangular Forum, as the Greeks wanted to control just the streets and the port.[11] At the same time the cult of Apollo was introduced.[12] Greek and Phoenician sailors used the location as a safe port.

Around the 6th century BC, it merged into a single community on the important crossroad between Cumae, Nola and Stabiae and was surrounded by a tufa city wall (the pappamonte wall).[13] It began to flourish and the first maritime trade started with the construction of a small port near the mouth of the river.[14] The earliest settlement was focussed in regions VII and VIII of the town (the altstadt) as identified from stratigraphy below the Samnite and Roman buildings.

524 BC saw the arrival and settlement of the Etruscans in the area including Pompeii, finding in the river Sarno a communication route between the sea and the interior. Similarly to the Greeks, the Etruscans did not conquer the city militarily, but simply controlled it and Pompeii enjoyed a sort of autonomy.[15] Nevertheless, Pompeii became a member of the Etruscan League of cities.[16] Recent[timeframe?] excavations have shown the presence of Etruscan inscriptions and a 6th-century BC necropolis. Under the Etruscans a primitive forum or simple market square was built, as well as the temple of Apollo, in both of which objects including fragments of bucchero were found by Maiuri.[17] Several houses were built with the so-called Tuscan atrium, typical of this people.[18]

The city wall was strengthened in the early 5th century BC with two façades of relatively thin, vertically set, slabs of Sarno limestone some 4 m apart filled with earth (the orthostate wall).[19]

In 474 BC the Greek city of Cumae, allied with Syracuse, conquered the Etruscans definitively at the Battle of Cumae and gained control of the area.

The Samnite period

City walls south of the Nocera gate

The period between about 450–375 BC witnessed large areas of the city being abandoned while important sanctuaries such as the Temple of Apollo show a sudden lack of votive material remains.[20]

The Samnites, people coming from the areas of Abruzzo and Molise, and allies of the Romans, conquered Greek Cumae between 423 and 420 BC and it is likely that in advance, all the surrounding territory, including Pompeii, was conquered around 424 BC. The new rulers gradually imposed their architecture and enlarged the town.

From 343 BC the first Roman army entered the Campanian plain bringing with it the customs and traditions of Rome and in the Roman war against the Latins the Samnites were faithful to Rome. Pompeii, although governed by the Samnites, entered in effect in the Roman orbit, to which it remained faithful even during the third Samnite war and in the war against Pyrrhus.

The city walls were reinforced in Sarno stone in the early 3rd century BC (the Limestone enceinte, or the first Samnite wall). It formed the basis for the currently visible walls with an outer wall of rectangular limestone blocks as an enormous terrace wall supporting a large agger, or earth embankment, behind it.

After the Samnite Wars from 290 BC, Pompeii was forced to accept the status of socii of Rome, maintaining, however, linguistic and administrative autonomy.

From the outbreak of the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) in which Pompeii remained faithful to Rome, an additional internal retaining wall was built and the agger and outer façade raised resulting in a double parapet with wider wall-walk.[21] Despite the political uncertainty of these events and the progressive migration of wealthy men to quieter cities in the eastern Mediterranean, Pompeii continued to flourish due to the production and trade of wine and oil with places like Provence and Spain,[22] as well as to intensive agriculture on farms around the city.

In the 2nd century BC, Pompeii enriched itself by taking part in Rome's conquest of the east as shown by a statue of Apollo in the Forum erected by Lucius Mummius in gratitude for their support in the sack of Corinth and the eastern campaigns. These riches enabled Pompeii to bloom and expand to its ultimate limits. The forum and many public and private buildings of high architectural quality were built, including the large theatre, the sanctuary to Jupiter, the Basilica, the Comitium, the Stabian baths and a new two-story portico.[23]

The Roman Period

Fresco of Terentius Neo and his wife from their house[24]

Pompeii took part in the Social Wars that the towns of Campania initiated against Rome, but in 89 BC it was besieged by Sulla. Although the battle-hardened troops of the Social League, headed by Lucius Cluentius, helped in resisting the Romans, in 89 BC Pompeii was forced to surrender after the conquest of Nola, culminating in many of Sulla's veterans being given land and property, while many of those who went against Rome were ousted from their homes. It became a Roman colony with the name of Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum. The town became an important passage for goods that arrived by sea and had to be sent toward Rome or southern Italy along the nearby Appian Way. Cicero, in one of his speeches, mentioned that there were lot of disputes between the native Oscans and the newly arrived Latin colonists, who seemed to have taken full control of the politics in Pompeii, until Sulla himself stepped up and resolved the issue. Couple of decades later, the Oscan names started appearing frequently in the local government, suggesting that the native inhabitants had become assimilated into their city's new status as a Roman colony.[25] Also some of Pompeii's old airstocratic families Latinized their names as a sign of assimilation, and there are evidence of marriages between the Oscans and Latins. [26]

From c. 20 BC, Pompeii was fed with water by a spur from the Serino aqueduct or Aqua Augusta (Naples) built by Agrippa; the main line supplied several other large towns and the important naval base at Misenum. The castellum aquae is well preserved, and includes many details of the distribution network and its controls.[27]

Illustrated reconstruction, from a CyArk/University of Ferrara research partnership, of how the Temple of Apollo may have looked before Mt. Vesuvius erupted

The same location today.

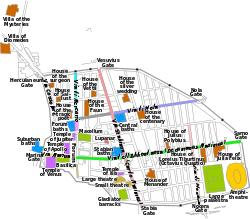

Annotated map of Pompeii

The main Forum in Pompeii

The Forum with Vesuvius in the distance

Amphitheatre of Pompeii

AD 62–79

The inhabitants of Pompeii had long been used to minor earthquakes (indeed, the writer Pliny the Younger wrote that earth tremors "were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania"), but on 5 February 62,[28] a severe earthquake did considerable damage around the bay, and particularly to Pompeii. It is believed that the earthquake would have registered between about 5 and 6 on the Richter magnitude scale.[29]

On that day in Pompeii, there were to be two sacrifices, as it was the anniversary of Augustus being named "Father of the Nation" and also a feast day to honour the guardian spirits of the city. Chaos followed the earthquake. Fires, caused by oil lamps that had fallen during the quake, added to the panic. Nearby cities of Herculaneum and Nuceria were also affected.[29]

Temples, houses, bridges, and roads were destroyed. It is believed that almost all buildings in the city of Pompeii were affected. In the days after the earthquake, anarchy ruled the city, where theft and starvation plagued the survivors. In the time between 62 and the eruption in 79, some rebuilding was done, but some of the damage had still not been repaired at the time of the eruption.[29] Although it is unknown how many, a considerable number of inhabitants moved to other cities within the Roman Empire while others remained and rebuilt.

An important field of current research concerns structures that were being restored at the time of the eruption (presumably damaged during the earthquake of 62). Some of the older, damaged paintings could have been covered with newer ones, and modern instruments are being used to catch a glimpse of the long hidden frescoes. The probable reason why these structures were still being repaired around 17 years after the earthquake was the increasing frequency of smaller quakes that led up to the eruption.

Eruption of Vesuvius

By the 1st century AD, Pompeii was one of a number of towns near the base of the volcano, Mount Vesuvius. The area had a substantial population, which had grown prosperous from the region's renowned agricultural fertility. Many of Pompeii's neighbouring communities, most famously Herculaneum, also suffered damage or destruction during the 79 eruption.[30]

Pompeii and other cities affected by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The black cloud represents the general distribution of ash and cinder. Modern coast lines are shown.

Roman fresco with a banquet scene from the Casa dei Casti Amanti, Pompeii

A multidisciplinary volcanological and bio-anthropological study of the eruption products and victims, merged with numerical simulations and experiments, indicates that at Pompeii and surrounding towns heat was the main cause of death of people, previously believed to have died by ash suffocation. The results of the study, published in 2010, show that exposure to at least 250 °C (482 °F) hot surges (known as pyroclastic flows) at a distance of 10 kilometres (6 miles) from the vent was sufficient to cause instant death, even if people were sheltered within buildings.[31] The people and buildings of Pompeii were covered in up to 12 different layers of tephra, in total 25 metres (82.0 ft) deep, which rained down for about six hours.

Pliny the Younger provided a first-hand account of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius from his position across the Bay of Naples at Misenum but written 25 years after the event. His uncle, Pliny the Elder, with whom he had a close relationship, died while attempting to rescue stranded victims. As admiral of the fleet, Pliny the Elder had ordered the ships of the Imperial Navy stationed at Misenum to cross the bay to assist evacuation attempts. Volcanologists have recognised the importance of Pliny the Younger's account of the eruption by calling similar events "Plinian". It had long been thought that the eruption was an August event based on one version of the letter but another version[32] gives a date of the eruption as late as 23 November. A later date is consistent with a charcoal inscription at the site, discovered in 2018, which includes the date of 17 October and which must have been recently written.[33][34]

Further support for an October/November eruption is found in the fact that people buried in the ash appear to have been wearing heavier clothing than the light summer clothes typical of August. The fresh fruit and vegetables in the shops are typical of October – and conversely the summer fruit typical of August was already being sold in dried, or conserved form. Wine fermenting jars had been sealed, which would have happened around the end of October. Coins found in the purse of a woman buried in the ash include one with a 15th imperatorial acclamation among the emperor's titles. These coins could not have been minted before the second week of September.[32]

Rediscovery

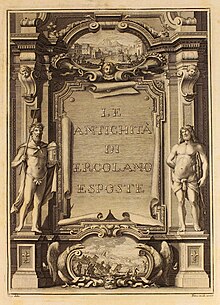

Beginning in 1757, the eight volumes of Le Antichità di Ercolano brought knowledge of Pompeii and Herculaneum to the fore.

"Garden of the Fugitives". Plaster casts of victims still in situ; many casts are in the Archaeological Museum of Naples.

Roman fresco from the Villa dei Misteri

Fresco from the Casa del Centenario bedroom

Soon after the burial of the city, some survivors or thieves came to salvage valuables, including marble statues from buildings. They left traces of their passage, as in a house where modern archaeologists found a wall graffitus saying "House dug".[35] During the following centuries, its name and location were forgotten. The earliest any part was unearthed was in 1592, when the digging of an underground channel to divert the river Sarno ran into ancient walls covered with paintings and inscriptions. The architect Domenico Fontana was called in; he unearthed a few more frescoes, then covered them over again, and nothing more came of the discovery. A wall inscription had mentioned a decurio Pompeii ("the town councillor of Pompeii") but its reference to the long-forgotten Roman city was missed.

Fontana's covering over the paintings has been seen both as a broad-minded act of preservation for later times, and as censorship of the hedonistic sexual wall images, which he would have known would scandalize counter-reformation Italy.[36]

Herculaneum was properly rediscovered in 1738 by workmen digging for the foundations of a summer palace for the King of Naples, Charles of Bourbon. The Spanish military engineer Rocque Joaquin de Alcubierre then undertook excavations to find further remains, discovering Pompeii in 1748.[36] Charles of Bourbon took great interest in the findings, even after leaving to become king of Spain, because the display of antiquities reinforced the political and cultural prestige of Naples.[37]

Karl Weber directed the first serious excavations;[38] he was followed in 1764 by military engineer Franscisco la Vega. Franscisco la Vega was succeeded by his brother, Pietro, in 1804.[39] During the French occupation Pietro worked with Christophe Saliceti.[40]

Giuseppe Fiorelli took charge of the excavations in 1863.[41] During early excavations of the site, occasional voids in the ash layer had been found that contained human remains. It was Fiorelli who realised these were spaces left by the decomposed bodies and so devised the technique of injecting plaster into them to recreate the forms of Vesuvius's victims. This technique is still in use today, with a clear resin now used instead of plaster because it is more durable, and does not destroy the bones, allowing further analysis.[42]

The discovery of erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum left the archaeologists with a dilemma – between the mores of sexuality in ancient Rome

and in Counter-Reformation Europe lay a clash of cultures. An unknown number of discoveries were hidden away again. A wall fresco depicting Priapus, the ancient god of sex and fertility, with his extremely enlarged penis, was covered with plaster. An older reproduction was locked away "out of prudishness" and opened only on request—and only rediscovered in 1998 due to rainfall.[43] In 2018, an ancient fresco depicting an erotic scene of "Leda and the Swan" was discovered at Pompeii.[44]

A large number of artefacts from the buried cities are preserved in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. In 1819, when King Francis visited the Pompeii exhibition there with his wife and daughter, he was so embarrassed by the erotic artwork that he decided to have it locked away in a so-called "secret cabinet" (gabinetto segreto), a gallery within the museum accessible only to "people of mature age and respected morals". Re-opened, closed, re-opened again and then closed again for nearly 100 years, the Naples "Secret Museum" was briefly made accessible again at the end of the 1960s (the time of the sexual revolution) and was finally re-opened for viewing in 2000. Minors are still allowed entry only in the presence of a guardian or with written permission.[45]

Roman city development

Via dell'Abbondanza, the main street in Pompeii.

Under the Romans, Pompeii underwent a vast process of urban development especially in the Augustan period. Public buildings include an amphitheatre, a palaestra with a central natatorium (cella natatoria) or swimming pool and an aqueduct that provided water for more than 25 street fountains, at least four public baths, and a large number of private houses (domūs) and businesses. The amphitheatre has been cited by modern scholars as a model of sophisticated design, particularly in the area of crowd control.[46]

Besides the forum, many other service areas were found: the Macellum (great food market), the Pistrinum (mill), the Thermopolium (a fast food place that served hot and cold dishes and beverages), and cauponae (cafes or 'dives' with a bad reputation as a hang out for thieves and prostitution services). An amphitheatre and two theatres have been found, along with a palaestra or gymnasium. A hotel (of 1,000 square metres) was found a short distance from the town; it is now nicknamed the "Grand Hotel Murecine". Geothermal energy supplied channelled district heating for baths and houses.[47] At least one building, the Lupanar, was dedicated to prostitution.[48]

Modern archaeologists have excavated garden sites and urban domains to reveal the agricultural staples in Pompeii's economy. Pompeii was fortunate to have a fruitful, fertile region of soil for harvesting a variety of crops. The soils surrounding Mount Vesuvius preceding its eruption have been revealed to have good water-holding capabilities, implying access to productive agriculture. The Tyrrhenian Sea’s airflow provided hydration to the soil despite the hot, dry climate.[49]Barley, wheat, and millet were all produced along with wine and olive oil, in abundance for export to other regions.[50]

Evidence of wine imported nationally from Pompeii in its most prosperous years can be found from recovered artefacts such as wine bottles in Rome.[50] For this reason, vineyards were of utmost importance to Pompeii's economy. Agricultural policymaker Columella suggested that each vineyard in Rome produced a quota of three cullei of wine per jugerum, otherwise the vineyard would be uprooted. The nutrient-rich lands near Pompeii were extremely efficient at this and were often able to exceed these requirements by a steep margin, therefore providing the incentive for local wineries to establish themselves.[50] While wine was exported for Pompeii's economy, the majority of the other agricultural goods were likely produced in quantities relevant to the city's consumption.

Remains of large formations of constructed wineries were found in the Forum Boarium, covered by cemented casts from the eruption of Vesuvius.[50] It is speculated that these historical vineyards are strikingly similar in structure to the modern day vineyards across Italy.

Carbonised food plant remains, roots, seeds and pollens, have been found from gardens in Pompeii, Herculaneum and from the Roman villa at Torre Annunziata. They revealed that emmer wheat, Italian millet, common millet, walnuts, pine nuts, chestnuts, hazel nuts, chickpeas, bitter vetch, broad beans, olives, figs, pears, onions, garlic, peaches, carob, grapes, and dates were consumed. All except the dates could have been produced locally.[51]

Tourism

A paved street. Pedestrians used the blocks in the road to cross the street without having to step onto the road, which doubled up as Pompeii's drainage and sewage disposal system. The spaces between the blocks let vehicles pass along the road.

The House of the Faun.

Pompeii has been a popular tourist destination for over 250 years;[52] it was on the Grand Tour. By 2008, it was attracting almost 2.6 million visitors per year, making it one of the most popular tourist sites in Italy.[53] It is part of a larger Vesuvius National Park and was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997. To combat problems associated with tourism, the governing body for Pompeii, the Soprintendenza Archaeological di Pompei, have begun issuing new tickets that allow for tourists to also visit cities such as Herculaneum and Stabiae as well as the Villa Poppaea, to encourage visitors to see these sites and reduce pressure on Pompeii.

Pompeii is also a driving force behind the economy of the nearby town of Pompei. Many residents are employed in the tourism and hospitality business, serving as taxi or bus drivers, waiters or hotel operators. The ruins can be easily reached on foot from Pompei Scavi-Villa dei Misteri station by Circumvesuviana commuter rail Naples – Sorrento route, directly at the ancient site. There are also car parks nearby.

Excavations in the site have generally ceased due to the moratorium imposed by the superintendent of the site, Professor Pietro Giovanni Guzzo. Additionally, the site is generally less accessible to tourists, with less than a third of all buildings open in the 1960s being available for public viewing today. Nevertheless, the sections of the ancient city open to the public are extensive, and tourists can spend several days exploring the whole site.

Conservation

Objects buried beneath Pompeii were well-preserved for almost 2,000 years. The lack of air and moisture let objects remain underground with little to no deterioration. Once excavated, the site provided a wealth of source material and evidence for analysis, giving detail into the lives of the Pompeiians. However, once exposed, Pompeii has been subject to both natural and man-made forces, which have rapidly increased deterioration.

Weathering, erosion, light exposure, water damage, poor methods of excavation and reconstruction, introduced plants and animals, tourism, vandalism and theft have all damaged the site in some way. Two-thirds of the city has been excavated, but the remnants of the city are rapidly deteriorating.[54]

The concern for conservation has continually troubled archaeologists. The ancient city was included in the 1996 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund, and again in 1998 and in 2000. In 1996 the organisation claimed that Pompeii "desperately need[ed] repair" and called for the drafting of a general plan of restoration and interpretation.[55] The organisation supported conservation at Pompeii with funding from American Express and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.[56]

Today, funding is mostly directed into conservation of the site; however, due to the expanse of Pompeii and the scale of the problems, this is inadequate in halting the slow decay of the materials. An estimated US$335 million is needed for all necessary work on Pompeii.[citation needed] A recent study has recommended an improved strategy for interpretation and presentation of the site as a cost-effective method of improving its conservation and preservation in the short term.[57]

In June 2013 UNESCO declared: If restoration and preservation works “fail to deliver substantial progress in the next two years,” Pompeii could be placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger.[58]

Fencing in the temple of Venus prevents vandalism of the site, as well as theft.

Indian art also found its way into Pompeii, within the context of Indo-Roman trade: in 1938 the Pompeii Lakshmi was found in the ruins of Pompeii.

House of the Gladiators collapse

The 2,000-year-old Schola Armatorum (House of the Gladiators) collapsed on 6 November 2010. The structure was not open to visitors, but the outside was visible to tourists. There was no immediate determination as to what caused the building to collapse, although reports suggested water infiltration following heavy rains might have been responsible. There has been fierce controversy after the collapse, with accusations of neglect.[59][60]

In popular culture

A Roman fresco from Pompeii, 1st century AD, depicting a man in a theatre mask and a woman wearing a garland while playing a lyre (a Greco-Roman stringed instrument); it is now housed in the National Archaeological Museum (Museo Archeologico Nazionale) of Naples

Pompeii was the setting for the British comedy television series Up Pompeii! and the movie of the series. Pompeii also featured in the second episode of the fourth season of revived BBC science fiction series Doctor Who, named "The Fires of Pompeii",[61] which featured Caecilius as a character.

In 1971, the rock band Pink Floyd filmed a live concert titled Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii, in which they performed six songs in the ancient Roman amphitheatre in the city. The audience consisted only of the film's production crew and some local children.

Siouxsie and the Banshees wrote and recorded the punk-inflected dance song "Cities in Dust", which describes the disaster that befell Pompeii and Herculaneum in A.D. 79. The song appears on their album Tinderbox, released in 1985, on Polydor Records. The jacket of the single remix of the song features the plaster cast of the chained dog killed in Pompeii.

Pompeii is a novel written by Robert Harris (published in 2003) featuring the account of the aquarius' race to fix the broken aqueduct in the days leading up to the eruption of Vesuvius, inspired by actual events and people.

"Pompeii" is a song by the British band Bastille, released 24 February 2013. The lyrics refer to the city and the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Pompeii is a 2014 German-Canadian historical disaster film produced and directed by Paul W. S. Anderson.[62]

In 2016, 45 years after the Pink Floyd recordings, band guitarist David Gilmour returned to the Pompeii amphiteatre to perform a live concert for his Rattle That Lock world tour. This event was considered the first one in the amphiteatre to feature an audience since the AD 79 eruption of Vesuvius.[63][64]

Documentaries

In Search of...'s episode No. 82 focuses entirely on Pompeii; it premiered on November 29, 1979.- The National Geographic special In the Shadow of Vesuvius (1987) explores the sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum, interviews (then) leading archaeologists, and examines the events leading up to the eruption of Vesuvius.[65]

Ancient Mysteries: Pompeii: Buried Alive (1996), an A&E television documentary narrated by Leonard Nimoy.[66]

Pompeii: The Last Day (2003), an hour-long drama produced for the BBC that portrays several characters (with historically attested names, but fictional life-stories) living in Pompeii, Herculaneum and around the Bay of Naples, and their last hours, including a fuller and his wife, two gladiators, and Pliny the Elder. It also portrays the facts of the eruption.

Pompeii and the AD 79 eruption (2004), a two-hour Tokyo Broadcasting System documentary.

Pompeii Live (June 28, 2006), a Channel 5 production featuring a live archaeological dig at Pompeii and Herculaneum[67][68]

Pompeii: The Mystery of the People Frozen in Time (2013), a BBC One drama documentary presented by Dr. Margaret Mountford.[69]

- "The Riddle of Pompeii" (May 23, 2014), Discovery Channel[70]

See also

Pompeii portal

Pompeii portal

- Eumachia

- House of Julia Felix

- House of Loreius Tiburtinus

- House of Menander

- House of Sallust

- House of the Tragic Poet

- House of the Vettii

- Macellum of Pompeii

Mastroberardino, a project with the Italian winery Mastroberardino to replant the vineyards of Pompeii

Robert Rive, 1850s photographer of Pompeii- Suburban Baths (Pompeii)

- Temple of Isis (Pompeii)

- Volcanic destruction

Armero tragedy, a city in Colombia that suffered a similar fate in 1985

Joya de Cerén, a pre-Columbian farming village in El Salvador known as the "Pompeii of the Americas"

Plymouth, Montserrat, former capital city buried by volcanic ash from the Soufrière Hills volcano in the 1990s

Saint-Pierre, Martinique, town similarly destroyed by the volcanic eruption of Mount Pelee, in 1902

- Other

Dura-Europos, also known as the "Pompeii of the desert"- Aeclanum

- Cumae

- Oplonti

- Stabiae

References

^ De Carolis & Patricelli 2003, p. 83

^ "Dossier Musei 2008" (PDF) (in Italian). Touring Club Italiano. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2012..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ http://www.pompeiisites.org/Sezione.jsp?titolo=Pompeii%2C+new+excavations+Regio+V&idSezione=7695

^ "Pompeii victim crushed by boulder while fleeing eruption". BBC. May 30, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

^ Squires, Nick (April 25, 2018). "Skeleton of child trying to shelter from Vesuvius eruption uncovered in Pompeii". The Telegraph. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

^ Squires, Nick (May 11, 2018). "Remains of ancient Roman horse found at Pompeii in dig started by tomb raiders". The Telegraph. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

^ Kraus 1975, p. [page needed]

^ Senatore, Stanley & Pescatore 2004, p. [page needed]

^ Wilson, Andrew (2011). "City Sizes and Urbanization in the Roman Empire". In Bowman, Alan; Wilson, Andrew. Settlement, Urbanization, and Population. Oxford Studies on the Roman Economy. 2. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-0-19-960235-3.

^ Arnold De Vos ; Mariette De Vos, Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabia, Rome, Giuseppe Laterza & figli Publishing House , 1982.

ISBN 88-420-2001-X

^ Robert Etienne, Daily Life in Pompeii , Milan, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore , 1992.

ISBN 88-04-35466-6 p. 62

^ Paul Zanker , Pompeii: society, urban images and forms of living , Turin, Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1993.

ISBN 88-06-13282-2 p. 60

^ Touring Club Italiano, Guida d'Italia – Naples and surroundings, Milan, Touring Club Editore, 2008.

ISBN 978-88-365-3893-5

^ Robert Etienne, Daily Life in Pompeii , Milan, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1992.

ISBN 88-04-35466-6

^ Robert Etienne, Daily Life in Pompeii , Milan, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1992.

ISBN 88-04-35466-6 p 63

^ W. Keller: The Etruscans

ISBN 9780224010719

^ Arnold De Vos ; Mariette De Vos, Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabia, Rome, Giuseppe Laterza & figli Publishing House, 1982.

ISBN 88-420-2001-X p. 8

^ Robert Etienne, Daily Life in Pompeii, Milan, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1992.

ISBN 88-04-35466-6 p. 64

^ Chiaramonte Treré: "The Walls and Gates", "The walls and gates," in Dobbins & Foss, eds., The World of Pompeii (Routledge 2007)

ISBN 0-203-86619-3

^ "The City Walls of Pompeii: Perceptions and Expressions of a Monumental Boundary" by Ivo van der Graaff, M.A. Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, p. 56

^ Robert Etienne, Daily Life in Pompeii, Milan, Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1992.

ISBN 88-04-35466-6 pp. 75–77

^ Paul Zanker, Pompeii: society, urban images and forms of living, Turin, Giulio Einaudi Editore, 1993.

ISBN 88-06-13282-2 p. 60

^ ecolo a.C." In Sicilia ellenistica, consuetudo italica. Alle origini dell’architettura ellenistica d’occidente. Spoleto, complesso monumentale di S. Nicolò, 5 – 7 Novembre 2004, edited by M. Osanna and M. Torelli (Pisa, 2006), 227–241.

^ Clarke 2006, pp. 262–264.

^ Beard, Mary (2008). Pompeii. Profile Books LTD. ISBN 978-1-86197-596-6.

^ Butterworth, Alex (2005). Pompeii - The Living City. St Martin's Press; 1st edition. ISBN 978-0-312-35585-2.

^ Lorenz, Wayne (June 2011). "Pompeii (and Rome) Water Supply Systems" (PDF). Wright Paleohydrological Institute. p. 26. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

^ "Patterns of Reconstruction at Pompeii". University of Virginia. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

^ abc "Visiting Pompeii". Current Archaeology. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 20, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

^ "The Destruction of Pompeii, AD 79". EyeWitness to History. 1999. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

^ Mastrolorenzo et al. 2010, p. e11127.

^ ab Stefani 2006, pp. 10–14.

^ "Pompeii's destruction date could be wrong". BBC News. October 16, 2018.

^ Gabi Laske. "The A.D. 79 Eruption at Mt. Vesuvius". Lecture notes for UCSD-ERTH15: "Natural Disasters". Archived from the original on 2008-12-29. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

^ Mary Beard, Pompeii. The life of a Roman city, Seuil, 2012 p 24

^ ab Ozgenel 2008, p. 13.

^ Ozgenel 2008, p. 19.

^ Parslow 1995, p. [page needed]

^ Pagano 1997, p. [page needed]

^ POMPEIA d'Ernest Breton (3eme éd. 1870) "Introduction – La résurrection de la ville" in French.

^ Nappo, Salvatore Ciro (February 17, 2011). "Pompeii: Its Discovery and Preservation". BBC. Retrieved March 2, 2013.Giuseppe Fiorelli directed the Pompeii excavation from 1863 to 1875

^ Gracco, Tiberio (28 April 2017). "Orto dei Fuggiaschi". Pompei Online. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

^ As reported by the Evangelist pressedienst press agency in March, 1998.

^ "Ancient erotic fresco uncovered in Pompeii ruins". CNN Style. 2018-11-20. Retrieved 2018-11-21.

^ Karl Schefold (2003), Die Dichtung als Führerin zur Klassischen Kunst. Erinnerungen eines Archäologen (Lebenserinnerungen Band 58), edd. M. Rohde-Liegle et al., Hamburg. p. 134

ISBN 3-8300-1017-6.

^ Berinato, Scott (May 18, 2007). "Crowd Control in Ancient Pompeii". CSO. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

^ Bloomquist, R. Gordon (2001). Geothermal District Energy System Analysis, Design, and Development (PDF). International Summer School. International Geothermal Association. p. 213(1). Retrieved November 28, 2015. Lay summary – Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences.During Roman times, warm water was circulated through open trenches to provide heating for buildings and baths in Pompeii.

^ Day, Michael (November 16, 2015). "Prostitution in Pompeii: 2,000 years after explosion, sex-for-cash is still rife". The Independent.the city's most extravagant brothel, the Lupanare – from the Latin word lupa for prostitute

^ Meyer, Frederick G (edited by Wilhelmina Feemster Jashemski) (2002). The natural history of Pompeii (1. publ. ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0521800549.

^ abcd Bernick, Christie. "Agriculture in Pompeii". Wall Paintings of the Pompeii Forum. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

^ Meyer, Frederick G. (October–December 1980). "Carbonized Food Plants of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the Villa at Torre Annunziata". New York Botanical Garden: Economic Botany. 34 (4): 419. JSTOR 4254221.

^ Rowland 2014.

^ Nadeau, Barbie Selling Pompeii, Newsweek, April 14, 2008.

^ Popham, Peter (May 2010). "Ashes to ashes: the latter-day ruin of Pompeii". Prospect Magazine. London. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

^ "World Monuments Fund, ''List of 100 Most Endangered Sites – 1996,'' New York, NY: 1996, p. 31" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-20. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

^ World Monuments Fund (2017). "Ancient Pompeii". Retrieved 23 June 2017.

^ Wallace, Alia (2012). "Presenting Pompeii: Steps towards Reconciling Conservation and Tourism at an Ancient Site". Papers from the Institute of Archaeology. Ubiquity Press. 22: 115–136. doi:10.5334/pia.406.

^ Hammer, Joshua. "The Fall and Rise and Fall of Pompeii". Retrieved 2015-07-01.

^ "Pompeii collapse prompts charges of official neglect".

^ "Pompeii Gladiator Training Centre Collapses".

^ "Doctor Who – News – Rome Sweet Rome". BBC. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

^ Sandy Schaefer (September 18, 2012). "Paul W.S. Anderson To Helm 'Pompeii'". Retrieved 2014-02-27.

^ Kreps, Daniel (March 16, 2016). "David Gilmour Sets First Pompeii Shows Since Pink Floyd's Concert Film". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

^ "David Gilmour live at Pompeii – a photo essay". The Guardian. July 14, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2017.It is the first time since the eruption of Vesuvius in AD79 that there has been an event with an audience in the venue.

^ "In the Shadow of Vesuvius". National Geographic. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

^ "Ancient Mysteries: Season 3, Episode 22". A&E. February 2, 1996. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

^ Shelley Hales; Joanna Paul (2011). Pompeii in the Public Imagination from Its Rediscovery to Today. Oxford University Press. p. 367. doi:10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199569366.001.0001. ISBN 9780199569366.The recent UK Channel 5 programme, transmitted live from Herculaneum on 29 June 2006...

^ "Shows". Five. Archived from the original on 2006-06-03.

^ "Pompeii: The Mystery of the People Frozen in Time". BBC. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

^ The Riddle of Pompeii. 23 May 2014 – via YouTube.

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Beard, Mary (2008). Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-596-6.

Butterworth, Alex; Laurence, Ray (2005). Pompeii: The Living City. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-35585-2.

Cioni, Rafaello; Gurioli, L; Lanza, R; Zanella, E (2004). "Temperatures of the A.D. 79 pyroclastic density current deposits (Vesuvius, Italy)". Journal of Geophysical Research. 109: 2207. Bibcode:2004JGRB..109.2207C. doi:10.1029/2002JB002251.

Clarke, John (2006). Visual Representation and Non-Elite Viewers in Italy, 100 BC – AD 315. University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-24815-1.

De Carolis, Ernesto; Patricelli, Giovanni (2003). Vesuvius, A.D. 79: the destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum. L'erma Di Bretschneider. ISBN 978-88-8265-199-2.

Fletcher, John (1835). The whole works of...John Flecter. Oxford University.*Grant, Michael (2001). Cities of Vesuvius: Pompeii and Herculaneum. Phoenix. ISBN 9781842122198.

Hodge, Trevor (2001). Roman Aqueducts & Water Supply. Duckworth. ISBN 9780715631713.

Kraus, Theodor (1975). Pompeii and Herculaneum: The Living Cities of the Dead. H. N. Abrams. ISBN 9780810904187.

Maiuri, Amedeo (1994). "Pompeii". Scientific American.

Mastrolorenzo, Giuseppe; Petrone, Pierpaolo; Pappalardo, Lucia; Guarino, Fabio (2010). Langowski, Jörg, ed. "Lethal Thermal Impact at Periphery of Pyroclastic Surges: Evidences at Pompeii". PLOS ONE. 5 (6): e11127. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511127M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011127. PMC 2886100. PMID 20559555.

Ozgenel, Lalo (15 April 2008). "A Tale of Two Cities: In Search of Ancient Pompeii and Herculaneum" (PDF). Journal of the Faculty of Archaeology. Ankara: Middle East Technical University. 25 (1): 1–25. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

Pagano, Mario (1997). I Diari di Scavo di Pompeii, Ercolano e Stabiae di Francesco e Pietro la Vega (1764–1810) (in Italian). L'Erma di Bretschneidein. ISBN 88-7062-967-8.

Parslow, Christopher (1995). Rediscovering antiquity: Karl Weber and the excavation of Herculaneum, Pompeii, and Stabiae. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47150-8.

Perring, Stefania (1991). Pompeii: The Wonders of the Ancient World Brought to Life in Vivid See-Through Reconstructions: Then and Now. Macmillan Books. ISBN 0-02-599461-1.

Rodríguez, Cristina (2008). Les mystères de Pompéi (in French). Éditions du Masque. ISBN 2-702-43404-5.

Rowland, Ingrid D. (2014). From Pompeii: The Afterlife of a Roman Town. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674047938.

Senatore, Maria; Stanley, Jean-Daniel; Pescatore, Tullio (November 7–10, 2004). "Avalanche-associated mass flows damaged Pompeii several times before the Vesuvius catastrophic eruption in the 79 CE". 2004 Denver Annual Meeting.

Stefani, Grete (October 2006). La vera data dell'eruzione. Archeo.

Steven, Ellis (2004). "The distribution of bars at Pompeii: Archaeological, spatial and viewshed analyses". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 17 (1). ISSN 1047-7594.

Zarmati, Louise (2005). Heinemann ancient and medieval history: Pompeii and Herculaneum. Heinemann. ISBN 1-74081-195-X.

External links

Library resources about Pompeii |

|

Official website

Pompeii at Curlie

Data on new excavations from the International Association for Classical Archaeology (AIAC)- Ancient History Encyclopedia – Pompeii

Forum of Pompeii Digital Media Archive (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), data from a University of Ferrara/CyArk research partnership

Romano-Campanian Wall-Painting (English, Italian, Spanish and French introduction) mainly focusing on wall-paintings from Pompeian houses and villas

N. Purcell; R. Talbert; T. Elliott; S. Gillies. "Places: 433032 (Pompeii)". Pleiades. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- Pompeii: The Mystery Of People Frozen In Time

- Annotated Google map and satellite view