Aztec Empire

Aztec Empire Triple Alliance Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1430–1521 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

State emblems | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Maximum extent of the Aztec Empire | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Mexico-Tenochtitlan (de facto) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Nahuatl (lingua franca) Also Otomí, Matlatzinca, Mazahua, Mazatec, Huaxtec, Tepehua, Popoloca, Popoluca, Tlapanec, Mixtec, Cuicatec, Trique, Zapotec, Zoque, Chochotec, Chinantec, Totonac, Cuitlatec, Pame, Mam, Tapachultec, Tarascan, among others | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Aztec polytheism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Hegemonic military confederation of allied city-states | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Huehuetlatoani of Tenochtitlan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1427–1440 | Itzcoatl (Alliance founder) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1520–1521 | Cuauhtémoc (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Huetlatoani of Texcoco | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1431–1440 | Nezahualcoyotl (Alliance founder) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1516–1520 | Cacamatzin (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Huetlatoani of Tlacopan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1400–1430 | Totoquihuatzin (Alliance founder) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1519–1524 | Tetlepanquetzaltzin (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Pre-Columbian era Age of Discovery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Foundation of the alliance[1] | 1430 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Spanish conquest | August 19, 1521 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1520[2] | 220,000 km2 (85,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Mexico | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Full list of monarchs at bottom of page.[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Aztec Empire |

|---|

Mythology |

Military · Codices |

History |

Spanish conquest of Mexico |

La Noche Triste |

Engineering |

Education |

Religion |

Cuisine |

Architecture |

The Aztec Empire, or the Triple Alliance (Classical Nahuatl: Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān, [ˈjéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥]), began as an alliance of three Nahua altepetl city-states: Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. These three city-states ruled the area in and around the Valley of Mexico from 1428 until the combined forces of the Spanish conquistadores and their native allies under Hernán Cortés defeated them in 1521.

The Triple Alliance was formed from the victorious factions in a civil war fought between the city of Azcapotzalco and its former tributary provinces.[3] Despite the initial conception of the empire as an alliance of three self-governed city-states, Tenochtitlan quickly became dominant militarily.[4] By the time the Spanish arrived in 1519, the lands of the Alliance were effectively ruled from Tenochtitlan, while the other partners in the alliance had taken subsidiary roles.

The alliance waged wars of conquest and expanded rapidly after its formation. At its height, the alliance controlled most of central Mexico as well as some more distant territories within Mesoamerica, such as the Xoconochco province, an Aztec exclave near the present-day Guatemalan border. Aztec rule has been described by scholars as "hegemonic" or "indirect".[5] The Aztecs left rulers of conquered cities in power so long as they agreed to pay semi-annual tribute to the Alliance, as well as supply military forces when needed for the Aztec war efforts. In return, the imperial authority offered protection and political stability, and facilitated an integrated economic network of diverse lands and peoples who had significant local autonomy.

The state religion of the empire was polytheistic, worshiping a diverse pantheon that included dozens of deities. Many had officially recognized cults large enough so that the deity was represented in the central temple precinct of the capital Tenochtitlan. The imperial cult, specifically, was that of Huitzilopochtli, the distinctive warlike patron god of the Mexica. Peoples in conquered provinces were allowed to retain and freely continue their own religious traditions, so long as they added the imperial god Huitzilopochtli to their local pantheons.

Contents

1 Etymology and definitions

2 History

2.1 Before the Aztec Empire

2.2 Aztec warfare

2.3 Tepanec War

2.4 Imperial reforms

2.5 Early years of expansion

2.6 Later years of expansion

2.7 Spanish conquest

3 Government

3.1 Central administration

3.2 Provincial administration

3.3 Schematic of hierarchy

3.4 Provincial structure

4 Ideology and state

5 Law

6 Rulers

7 See also

8 References

9 Bibliography

9.1 Primary sources

9.2 Secondary sources

Etymology and definitions

The word "Aztec" in modern usage would not have been used by the people themselves. It has variously been used to refer to the Triple Alliance empire, the Nahuatl-speaking people of central Mexico prior to the Spanish conquest, or specifically the Mexica ethnicity of the Nahuatl-speaking peoples.[6] The name comes from a Nahuatl word meaning "people from Aztlan," reflecting the mythical place of origin for Nahua peoples.[7] For the purpose of this article, "Aztec" refers only to those cities that constituted or were subject to the Triple Alliance. For the broader use of the term, see the article on Aztec civilization.

History

Before the Aztec Empire

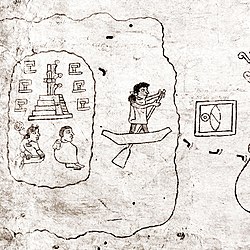

First page of Codex Boturini, showing the migration of the Mexica

Nahua peoples descended from Chichimec peoples who migrated to central Mexico from the north in the early 13th century.[8] The migration story of the Mexica is similar to those of other polities in central Mexico, with supernatural sites, individuals, and events, joining earthly and divine history as they sought political legitimacy.[9] According to the pictographic codices in which the Aztecs recorded their history, the place of origin was called Aztlán. Early migrants settled the Basin of Mexico and surrounding lands by establishing a series of independent city-states. These early Nahua city-states or altepetl, were ruled by dynastic heads called tlahtohqueh (singular, tlatoāni). Most of the existing settlements had been established by other indigenous peoples before the Mexica migration.[10]

These early city-states fought various small-scale wars with each other, but due to shifting alliances, no individual city gained dominance.[11] The Mexica were the last of the Nahua migrants to arrive in Central Mexico. They entered the Basin of Mexico around the year 1250 AD, and by then most of the good agricultural land had already been claimed.[12] The Mexica persuaded the king of Culhuacan, a small city-state but important historically as a refuge of the Toltecs, to allow them to settle in a relatively infertile patch of land called Chapultepec (Chapoltepēc, "in the hill of grasshoppers"). The Mexica served as mercenaries for Culhuacan.[13]

After the Mexica served Culhuacan in battle, the ruler appointed one of his daughters to rule over the Mexica. According to mythological native accounts, the Mexica instead sacrificed her by flaying her skin, on the command of their god Xipe Totec.[14] When the ruler of Culhuacan learned of this, he attacked and used his army to drive the Mexica from Tizaapan by force. The Mexica moved to an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, where, as legend is said to have predicted, an eagle nested on a nopal cactus. The Mexica interpreted this as a sign from their god and founded their new city, Tenochtitlan, on this island in the year ōme calli, or "Two House" (1325 AD).[3]

Aztec warfare

The Mexica rose to prominence as fierce warriors and were able to establish themselves as a military power. The importance of warriors and the integral nature of warfare in Mexica political and religious life helped propel them to emerge as the dominant military power prior to the arrival of the Spanish in 1519.

The new Mexica city-state allied with the city of Azcapotzalco and paid tribute to its ruler, Tezozomoc.[15] With Mexica assistance, Azcopotzalco began to expand into a small tributary empire. Until this point, the Mexica ruler was not recognized as a legitimate king. Mexica leaders successfully petitioned one of the kings of Culhuacan to provide a daughter to marry into the Mexica line. Their son, Acamapichtli, was enthroned as the first tlatoani of Tenochtitlan in the year 1372.[16]

While the Tepanecs of Azcapotzalco expanded their rule with help from the Mexica, the Acolhua city of Texcoco grew in power in the eastern portion of the lake basin. Eventually, war erupted between the two states, and the Mexica played a vital role in the conquest of Texcoco. By then, Tenochtitlan had grown into a major city and was rewarded for its loyalty to the Tepanecs by receiving Texcoco as a tributary province.[17]

Tepanec War

In 1426, the Tepanec king Tezozomoc died, and the resulting succession crisis precipitated a civil war between potential successors.[17] The Mexica supported Tezozomoc's preferred heir, Tayahauh, who was initially enthroned as king. But his son, Maxtla, soon usurped the throne and turned against factions that opposed him, including the Mexica ruler Chimalpopoca. The latter died shortly thereafter, possibly assassinated by Maxtla.[12]

The new Mexica ruler Itzcoatl continued to defy Maxtla; he blockaded Tenochtitlan and demanded increased tribute payments.[18] Maxtla similarly turned against the Acolhua, and the king of Texcoco, Nezahualcoyotl, fled into exile. Nezahualcoyotl recruited military help from the king of Huexotzinco, and the Mexica gained the support of a dissident Tepanec city, Tlacopan. In 1427, Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, Tlacopan, and Huexotzinco went to war against Azcapotzalco, emerging victorious in 1428.[18]

After the war, Huexotzinco withdrew, and in 1430 [1], the three remaining cities formed a treaty known today as the Triple Alliance.[18] The Tepanec lands were carved up among the three cities, whose leaders agreed to cooperate in future wars of conquest. Land acquired from these conquests was to be held by the three cities together. Tribute was to be divided so that two-fifths each went to Tenochtitlan and Texcoco, and one-fifth went to Tlacopan. Each of the three kings of the alliance in turn assumed the title "huetlatoani" ("Elder Speaker", often translated as "Emperor"). In this role, each temporarily held a de jure position above the rulers of other city-states ("tlatoani").[19]

In the next 100 years, the Triple Alliance of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan came to dominate the Valley of Mexico and extend its power to the shores of the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific. Tenochtitlan gradually became the dominant power in the alliance. Two of the primary architects of this alliance were the half-brothers Tlacaelel and Moctezuma, nephews of Itzcoatl. Moctezuma eventually succeeded Itzcoatl as the Mexica huetlatoani in 1440. Tlacaelel occupied the newly created title of "Cihuacoatl", equivalent to something between "Prime Minister" and "Viceroy".[18][20]

Imperial reforms

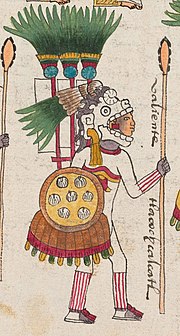

Jaguar Warrior, from the Codex Magliabechiano.

Shortly after the formation of the Triple Alliance, Itzcoatl and Tlacopan instigated sweeping reforms on the Aztec state and religion. It has been alleged that Tlacaelel ordered the burning of some or most of the extant Aztec books, claiming that they contained lies and that it was "not wise that all the people should know the paintings".[21] Even if he did order such book-burnings, it was probably limited primarily to documents containing political propaganda from previous regimes; he thereafter rewrote the history of the Aztecs, naturally placing the Mexica in a more central role.

After Moctezuma I succeeded Itzcoatl as the Mexica emperor, more reforms were instigated to maintain control over conquered cities.[22] Uncooperative kings were replaced with puppet rulers loyal to the Mexica. A new imperial tribute system established Mexica tribute collectors that taxed the population directly, bypassing the authority of local dynasties. Nezahualcoyotl also instituted a policy in the Acolhua lands of granting subject kings tributary holdings in lands far from their capitals.[23] This was done to create an incentive for cooperation with the empire; if a city's king rebelled, he lost the tribute he received from foreign land. Some rebellious kings were replaced by calpixqueh, or appointed governors rather than dynastic rulers.[23]

Moctezuma issued new laws that further separated nobles from commoners and instituted the death penalty for adultery and other offenses.[24] By royal decree, a religiously supervised school was built in every neighborhood.[24] Commoner neighborhoods had a school called a "telpochcalli" where they received basic religious instruction and military training.[25] A second, more prestigious type of school called a "calmecac" served to teach the nobility, as well as commoners of high standing seeking to become priests or artisans. Moctezuma also created a new title called "quauhpilli" that could be conferred on commoners.[22] This title was a form of non-hereditary lesser nobility awarded for outstanding military or civil service (similar to the English knight). In some rare cases, commoners that received this title married into royal families and became kings.[23]

One component of this reform was the creation of an institution of regulated warfare called the Flower Wars. Mesoamerican warfare overall is characterized by a strong preference for capturing live prisoners as opposed to slaughtering the enemy on the battlefield, which was considered sloppy and gratuitous. The Flower Wars are a potent manifestation of this approach to warfare. These highly ritualized wars ensured a steady, healthy supply of experienced Aztec warriors as well as a steady, healthy supply of captured enemy warriors for sacrifice to the gods. Flower wars were pre-arranged by officials on both sides and conducted specifically for the purpose of each polity collecting prisoners for sacrifice.[26] According to native historical accounts, these wars were instigated by Tlacaelel as a means of appeasing the gods in response to a massive drought that gripped the Basin of Mexico from 1450 to 1454.[27] The flower wars were mostly waged between the Aztec Empire and the neighboring cities of their arch-enemy Tlaxcala.

Early years of expansion

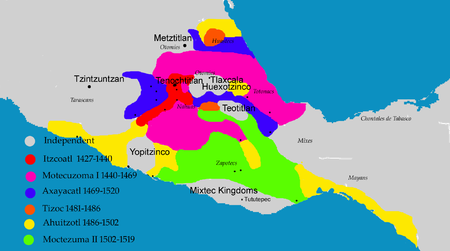

Map of the expansion of the empire, showing the areas conquered by the Aztec rulers.[28]

After the defeat of the Tepanecs, Itzcoatl and Nezahualcoyotl rapidly consolidated power in the Basin of Mexico and began to expand beyond its borders. The first targets for imperial expansion were Coyoacan in the Basin of Mexico and Cuauhnahuac and Huaxtepec in the modern Mexican state of Morelos.[29] These conquests provided the new empire with a large influx of tribute, especially agricultural goods.

On the death of Itzcoatl, Moctezuma I was enthroned as the new Mexica emperor. The expansion of the empire was briefly halted by a major four-year drought that hit the Basin of Mexico in 1450, and several cities in Morelos had to be re-conquered after the drought subsided.[30] Moctezuma and Nezahualcoyotl continued to expand the empire east towards the Gulf of Mexico and south into Oaxaca. In 1468, Moctezuma I died and was succeeded by his son, Axayacatl. Most of Axayacatl's thirteen-year-reign was spent consolidating the territory acquired under his predecessor. Motecuzoma and Nezahualcoyotl had expanded rapidly and many provinces rebelled.[12]

At the same time as the Aztec Empire was expanding and consolidating power, the Purépecha Empire in West Mexico was similarly expanding. In 1455, the Purépecha under their king Tzitzipandaquare had invaded the Toluca Valley, claiming lands previously conquered by Motecuzoma and Itzcoatl.[31] In 1472, Axayacatl re-conquered the region and successfully defended it from Purépecha attempts to take it back. In 1479, Axayacatl launched a major invasion of the Purépecha Empire with 32,000 Aztec soldiers.[31] The Purépecha met them just across the border with 50,000 soldiers and scored a resounding victory, killing or capturing over 90% of the Aztec army. Axayacatl himself was wounded in the battle, retreated to Tenochtitlan, and never engaged the Purépecha in battle again.[32]

In 1472, Nezahualcoyotl died and his son Nezahualpilli was enthroned as the new huetlatoani of Texcoco.[33] This was followed by the death of Axayacatl in 1481.[32] Axayacatl was replaced by his brother Tizoc. Tizoc's reign was notoriously brief. He proved to be ineffectual and did not significantly expand the empire. Apparently due to his incompetence, Tizoc was likely assassinated by his own nobles five years into his rule.[32]

Later years of expansion

The maximal extent of the Aztec Empire, according to María del Carmen Solanes Carraro and Enrique Vela Ramírez.

Tizoc was succeeded by his brother Ahuitzotl in 1486. Like his predecessors, the first part of Ahuitzotl's reign was spent suppressing rebellions that were commonplace due to the indirect nature of Aztec rule.[32] Ahuitzotl then began a new wave of conquests including the Oaxaca Valley and the Soconusco Coast. Due to increased border skirmishes with the Purépechas, Ahuitzotl conquered the border city of Otzoma and turned the city into a military outpost.[34] The population of Otzoma was either killed or dispersed in the process.[31] The Purépecha subsequently established fortresses nearby to protect against Aztec expansion.[31] Ahuitzotl responded by expanding further west to the Pacific Coast of Guerrero.

By the reign of Ahuitzotl, the Mexica were the largest and most powerful faction in the Aztec Triple Alliance.[35] Building on the prestige the Mexica had acquired over the course of the conquests, Ahuitzotl began to use the title "huehuetlatoani" ("Eldest Speaker") to distinguish himself from the rulers of Texcoco and Tlacopan.[32] Even though the alliance still technically ran the empire, the Mexica Emperor now assumed nominal if not actual seniority.

Ahuitzotl was succeeded by his nephew Motecuzoma II in 1502. Motecuzoma II spent most of his reign consolidating power in lands conquered by his predecessors.[34] In 1515, Aztec armies commanded by the Tlaxcalan general Tlahuicole invaded the Purépecha Empire once again.[36] The Aztec army failed to take any territory and was mostly restricted to raiding. The Purépechas defeated them and the army withdrew.

Motecuzoma II instituted more imperial reforms.[34] After the death of Nezahualcoyotl, the Mexica Emperors had become the de facto rulers of the alliance. Motecuzoma II used his reign to attempt to consolidate power more closely with the Mexica Emperor.[37] He removed many of Ahuitzotl's advisors and had several of them executed.[34] He also abolished the "quauhpilli" class, destroying the chance for commoners to advance to the nobility. His reform efforts were cut short by the Spanish Conquest in 1519.

Spanish conquest

The Valley of Mexico at the time of the Spanish Conquest.

The Aztec Empire in 1519

Spanish expedition leader Hernán Cortés landed in Yucatán in 1519 with approximately 630 men (most armed with only a sword and shield). Cortés had actually been removed as the expedition's commander by the governor of Cuba, Diego Velásquez, but had stolen the boats and left without permission.[38] At the island of Cozumel, Cortés encountered a shipwrecked Spaniard named Gerónimo de Aguilar who joined the expedition and translated between Spanish and Mayan. The expedition then sailed west to Campeche, where after a brief battle with the local army, Cortés was able to negotiate peace through his interpreter, Aguilar. The King of Campeche gave Cortés a second translator, a bilingual Nahua-Maya slave woman named La Malinche (she was known also as Malinalli [maliˈnalːi], Malintzin [maˈlintsin] or Doña Marina [ˈdoɲa maˈɾina] ). Aguilar translated from Spanish to Mayan and La Malinche translated from Mayan to Nahuatl. Once Malinche learned Spanish, she became Cortés's translator for both language and culture, and was a key figure in interactions with Nahua rulers. An important article, "Rethinking Malinche" by Frances Karttunen examines her role in the conquest and beyond.[39]

Cortés then sailed from Campeche to Cempoala, a tributary province of the Aztec Triple Alliance. Nearby, he founded the town of Veracruz where he met with ambassadors from the reigning Mexica emperor, Motecuzoma II. When the ambassadors returned to Tenochtitlan, Cortés went to Cempoala to meet with the local Totonac leaders. After the Totonac ruler told Cortés of his various grievances against the Mexica, Cortés convinced the Totonacs to imprison an imperial tribute collector.[40] Cortés subsequently released the tribute collector after persuading him that the move was entirely the Totonac's idea and that he had no knowledge of it. Having effectively declared war on the Aztecs, the Totonacs provided Cortés with 20 companies of soldiers for his march to Tlaxcala.[41] At this time several of Cortés's soldiers attempted to mutiny. When Cortés discovered the plot, he had his ships scuttled and sank them in the harbor to remove any possibility of escaping to Cuba.[42]

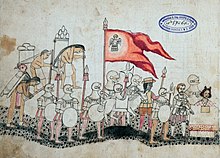

Codex Azcatitlan depicting the Spanish army, with Cortez and Malinche in front

The Spanish-led Totonac army crossed into Tlaxcala to seek the latter's alliance against the Aztecs. However, the Tlaxcalan general Xicotencatl the Younger believed them to be hostile, and attacked. After fighting several close battles, Cortés eventually convinced the leaders of Tlaxcala to order their general to stand down. Cortés then secured an alliance with the people of Tlaxcala, and traveled from there to the Basin of Mexico with a smaller company of 5,000-6,000 Tlaxcalans and 400 Totonacs, in addition to the Spanish soldiers.[42] During his stay in the city of Cholula, Cortés claims he received word of a planned ambush against the Spanish.[42] In a pre-emptive response, Cortés directed his troops attack and kill a large number of unarmed Cholulans gathered in the main square of the city.

Following the massacre at Cholula, Hernan Cortés and the other Spaniards entered Tenochtitlan, where they were greeted as guests and given quarters in the palace of former emperor Axayacatl.[43] After staying in the city for six weeks, two Spaniards from the group left behind in Veracruz were killed in an altercation with an Aztec lord named Quetzalpopoca. Cortés claims that he used this incident as an excuse to take Motecuzoma prisoner under threat of force.[42] For several months, Motecuzoma continued to run the kingdom as a prisoner of Hernan Cortés. Then, in 1520, a second, larger Spanish expedition arrived under the command of Pánfilo de Narváez sent by Diego Velásquez with the goal of arresting Cortés for treason. Before confronting Narváez, Cortés secretly persuaded Narváez's lieutenants to betray him and join Cortés.[42]

While Cortés was away from Tenochtitlan dealing with Narváez, his second in command Pedro de Alvarado massacred a group of Aztec nobility in response to a ritual of human sacrifice honoring Huitzilopochtli.[42] The Aztecs retaliated by attacking the palace where the Spanish were quartered. Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan and fought his way to the palace. He then took Motecuzoma up to the roof of the palace to ask his subjects to stand down. However, by this point the ruling council of Tenochtitlan had voted to depose Motecuzoma and had elected his brother Cuitlahuac as the new emperor.[43] One of the Aztec soldiers struck Motecuzoma in the head with a sling stone, and he died several days later – although the exact details of his death, particularly who was responsible, are unclear.[43]

Cristóbal de Olid led Spanish soldiers with Tlaxcalan allies in the conquests of Jalisco and Colima of West Mexico.

The Spaniards and their allies, realizing they were vulnerable to the hostile Mexica in Tenochtitlan following Moctezuma's death, attempted to retreat without detection in what is known as the "Sad Night" or La Noche Triste. Spaniards and their Indian allies were discovered clandestinely retreating, and then were forced to fight their way out of the city, with heavy loss of life. Some Spaniards lost their lives by drowning, loaded down with gold.[44] They retreated to Tlacopan (now Tacuba) and made their way to Tlaxcala, where they recovered and prepared for the second, successful assault on Tenochtitlan. After this incident, a smallpox outbreak hit Tenochtitlan. As the indigenous of the New World had no previous exposure to smallpox, this outbreak alone killed more than 50% of the region's population, including the emperor, Cuitlahuac.[45] While the new emperor Cuauhtémoc dealt with the smallpox outbreak, Cortés raised an army of Tlaxcalans, Texcocans, Totonacs, and others discontent with Aztec rule. With a combined army of up to 100,000 warriors,[42] the overwhelming majority of which were indigenous rather than Spanish, Cortés marched back into the Basin of Mexico. Through numerous subsequent battles and skirmishes, he captured the various indigenous city-states or altepetl around the lake shore and surrounding mountains, including the other capitals of the Triple Alliance, Tlacopan and Texcoco. Texcoco in fact had already become firm allies of the Spaniards and the city-state, and subsequently petitioned the Spanish crown for recognition of their services in the conquest, just as Tlaxcala had done.[46]

Using boats constructed in Texcoco from parts salvaged from the scuttled ships, Cortés blockaded and laid siege to Tenochtitlan for a period of several months.[42] Eventually, the Spanish-led army assaulted the city both by boat and using the elevated causeways connecting it to the mainland. Although the attackers took heavy casualties, the Aztecs were ultimately defeated. The city of Tenochtitlan was thoroughly destroyed in the process. Cuauhtémoc was captured as he attempted to flee the city. Cortés kept him prisoner and tortured him for a period of several years before finally executing him in 1525.[47]

Government

The Aztec Empire was an example of an empire that ruled by indirect means.

Like most European empires, it was ethnically very diverse, but unlike most European empires, it was more a system of tributes than a single unitary form of government. In the theoretical framework of imperial systems posited by American historian Alexander J. Motyl the Aztec empire was an informal type of empire in that the Alliance did not claim supreme authority over its tributary provinces; it merely expected tributes to be paid.[48] The empire was also territorially discontinuous, i.e. not all of its dominated territories were connected by land. For example, the southern peripheral zones of Xoconochco were not in immediate contact with the central part of the empire. The hegemonic nature of the Aztec empire can be seen in the fact that generally local rulers were restored to their positions once their city-state was conquered and the Aztecs did not interfere in local affairs as long as the tribute payments were made.[49]

Although the form of government is often referred to as an empire, in fact most areas within the empire were organized as city-states (individually known as altepetl in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs). These were small polities ruled by a king or tlatoani (literally "speaker", plural tlatoque) from an aristocratic dynasty. The Early Aztec period was a time of growth and competition among altepeme. Even after the empire was formed in 1428 and began its program of expansion through conquest, the altepetl remained the dominant form of organization at the local level. The efficient role of the altepetl as a regional political unit was largely responsible for the success of the empire's hegemonic form of control.[50]

It should be remembered that the term "Aztec empire" is a modern one, not one used by the Aztec themselves. The Aztec realm was at its core composed of three Nahuatl-speaking city states in the densely populated Valley of Mexico. Over time, asymmetries of power elevated one of those city states, Tenochtitlan, above the other two. The "Triple Alliance" came to establish hegemony over much of central Mesoamerica, including areas of great linguistic and cultural diversity. Administration of the empire was performed through largely traditional, indirect means. However, over time something of a nascent bureaucracy may have been beginning to form insofar as the state organization became increasingly centralized.

Central administration

A tlacochcalcatl pictured in the Codex Mendoza

Before the reign of Nezahualcoyotl (1429–1472), the Aztec empire operated as a confederation along traditional Mesoamerican lines. Independent altepetl were led by tlatoani (lit., "speakers"), who supervised village headmen, who in turn supervised groups of households. A typical Mesoamerican confederation placed a Huey Tlatoani (lit., "great speaker") at the head of several tlatoani. Following Nezahualcoyotl, the Aztec empire followed a somewhat divergent path, with some tlatoani of recently conquered or otherwise subordinated altepetl becoming replaced with calpixque stewards charged with collecting tribute on behalf of the Huetlatoani rather than simply replacing an old tlatoque with new ones from the same set of local nobility.[51]

Yet the Huey tlatoani was not the sole executive. It was the responsibility of the Huey tlatoani to deal with the external issues of empire; the management of tribute, war, diplomacy, and expansion were all under the purview of the Huey tlatoani. It was the role of the Cihuacoatl to govern the city of Tenochtitlan itself. The Cihuacoatl was always a close relative of the Huey tlatoani; Tlacaelel, for example, was the brother of Moctezuma I. Both the title "Cihuacoatl", which means "female snake" (it is the name of a Nahua deity), and the role of the position, somewhat analogous to a European Viceroy or Prime Minister, reflect the dualistic nature of Nahua cosmology. Neither the position of Cihuacoatl nor the position of Huetlatoani were priestly, yet both did have important ritual tasks. Those of the former were associated with the "female" wet season, those of the latter with the "male" dry season. While the position of Cihuacoatl is best attested in Tenochtitlan, it is known that the position also existed the nearby altepetl of Atzcapotzalco, Culhuacan, and Tenochtitlan's ally Texcoco. Despite the apparent lesser status of the position, a Cihuacoatl could prove both influential and powerful, as in the case of Tlacaelel.[52][53]

Early in the history of the empire, Tenochtitlan developed a four-member military and advisory Council which assisted the Huey tlatoani in his decision-making: the tlacochcalcatl; the tlaccatecatl; the ezhuahuacatl;[54] and the tlillancalqui. This design not only provided advise for the ruler, it also served to contain ambition on the part of the nobility, as henceforth Huey Tlatoani could only be selected from the Council. Moreover, the actions of any one member of the Council could easily be blocked by the other three, providing a simple system of checks on the ambition higher officials. These four Council members were also generals, members of various military societies. The ranks of the members were not equal, with the tlacochcalcatl and tlaccatecatl having a higher status than the others. These two Councillors were members of the two most prestigious military societies, the cuauhchique ("shorn ones") and the otontin ("Otomies").[55][56]

Provincial administration

Traditionally, provinces and altepetl were governed by hereditary tlatoani. As the empire grew, the system evolved further and some tlatoani were replaced by other officials.The other officials had similar authority to tlatoani. As has already been mentioned, directly appointed stewards (singular calpixqui, plural calpixque) were sometimes imposed on altepetl instead of the selection of provincial nobility to the same position of tlatoani. At the height of empire, the organization of the state into tributary and strategic provinces saw an elaboration of this system. The 38 tributary provinces fell under the supervision of high stewards, or huecalpixque, whose authority extended over the lower-ranking calpixque. These calpixque and huecalpixque were essentially managers of the provincial tribute system which was overseen and coordinated in the paramount capital of Tenochtitlan not by the huetlatoani, but rather by a separate position altogether: the petlacalcatl. On the occasion that a recently conquered altepetl was seen as particularly restive, a military governor, or cuauhtlatoani, was placed at the head of provincial supervision.[57] During the reign of Moctezuma I, the calpixque system was elaborated, with two calpixque assigned per tributary province. One was stationed in the province itself, perhaps for supervising the collection of tribute, and the other in Tenochtitlan, perhaps for supervising storage of tribute. Tribute was drawn from commoners, the macehualtin, and distributed to the nobility, be they 'kings' (tlatoque), lesser rulers (teteuctin), or provincial nobility (pipiltin).[58]

Tribute collection was supervised by the above officials and relied upon the coercive power of the Aztec military, but also upon the cooperation of the pipiltin (the local nobility who were themselves exempt from and recipient to tribute) and the hereditary class of merchants known as pochteca. These pochteca had various gradations of ranks which granted them certain trading rights and so were not necessarily pipiltin themselves, yet they played an important role in both the growth and administration of the Aztec tributary system nonetheless. The power, political and economic, of the pochteca was strongly tied to the political and military power of the Aztec nobility and state. In addition to serving as diplomats (teucnenenque, or "travelers of the lord") and spies in the prelude to conquest, higher-ranking pochteca also served as judges in market plazas and were to certain degree autonomous corporate groups, having administrative duties within their own estate.[59][60]

Schematic of hierarchy

| Executive & Military | Tribute System | Judicial System | Provincial System |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Provincial structure

Territorial Organization of the Aztec Empire 1519

Originally, the Aztec empire was loose alliance between three cities: Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and the most junior partner, Tlacopan. As such, they were known as the 'Triple Alliance.' This political form was very common in Mesoamerica, where alliances of city-states were ever fluctuating. However, over time, it was Tenochtitlan which assumed paramount authority in the alliance, and although each partner city shared spoils of war and rights to regular tribute from the provinces and were governed by their own Huetlatoani, it was Tenochtitlan which became the largest, most powerful, and most influential of the three cities. It was the de facto and acknowledged center of empire.[61]

Though they were not described by the Aztec this way, there were essentially two types of provinces: Tributary and Strategic. Strategic provinces were essentially subordinate client states which provided tribute or aid to the Aztec state under "mutual consent". Tributary provinces, on the other hand, provided regular tribute to the empire; obligations on the part of Tributary provinces were mandatory rather than consensual.[62][63]

Organization of the Aztec Empire[62][63] | ||

|---|---|---|

| The Triple Alliance | Provinces | |

Nahuatl glyphs for Texcoco, Tenochtitlan, and Tlacopan. | Tributary Provinces | Strategic Provinces |

|

| |

Ideology and state

This page from the Codex Tovar depicts a scene of gladiatorial sacrificial rite, celebrated on the festival of Tlacaxipehualiztli.

Rulers, be they local teteuctin or tlatoani, or central Huetlatoani, were seen as representatives of the gods and therefore ruled by divine right. Tlatocayotl, or the principle of rulership, established that this divine right was inherited by descent. Political order was therefore also a cosmic order, and to kill a tlatoani was to transgress that order. For that reason, whenever a tlatoani was killed or otherwise removed from their station, a relative and member of the same bloodline was typically placed in their stead. The establishment of the office of Huetlatoani understood through the creation of another level of rulership, hueitlatocayotl, standing in superior contrast to the lesser tlatocayotl principle.[64]

Expansion of the empire was guided by a militaristic interpretation of Nahua religion, specifically a devout veneration of the sun god, Huitzilopochtli. Militaristic state rituals were performed throughout the year according to a ceremonial calendar of events, rites, and mock battles.[65] The time period they lived in was understood as the Ollintonatiuh, or Sun of Movement, which was believed to be the final age after which humanity would be destroyed. It was under Tlacaelel that Huitzilopochtli assumed his elevated role in the state pantheon and who argued that it was through blood sacrifice that the Sun would be maintained and thereby stave off the end of the world. It was under this new, militaristic interpretation of Huitzilopochtli that Aztec soldiers were encouraged to fight wars and capture enemy soldiers for sacrifice. Though blood sacrifice was common in Mesoamerica, the scale of human sacrifice under the Aztecs was likely unprecedented in the region.[66]

Law

The most developed code of law was developed in the city-state of Texcoco under its ruler Nezahualcoyotl. It was a formal written code, not merely a collection of customary practices. The sources for knowing about the legal code are colonial-era writings by Franciscan Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, Franciscan Fray Juan de Torquemada, and Texcocan historians Juan Bautista Pomar, and Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl. The law code in Texcoco under Nezahualcoyotl was legalistic, that is cases were tried by particular types of evidence and the social status of the litigants was disregarded, and consisted of 80 written laws. These laws called for severe, publicly administered punishments, creating a legal framework of social control.[67]

Much less is known about the legal system in Tenochtitlan, which might be less legalistic or sophisticated as those of Texcoco for this period.[68] It was established under the reign of Moctezuma I. These laws served to establish and govern relations between the state, classes, and individuals. Punishment was to be meted out solely by state authorities. Nahua mores were enshrined in these laws, criminalizing public acts of homosexuality, drunkenness, and nudity, not to mention more universal proscriptions against theft, murder, and property damage. As stated before, pochteca could serve as judges, often exercising judicial oversight of their own members. Likewise, military courts dealt with both cases within the military and without during wartime. There was an appeal process, with appellate courts standing between local, typically market-place courts, on the provincial level and a supreme court and two special higher appellate courts at Tenochtitlan. One of those two special courts dealt with cases arising within Tenochtitlan, the other with cases originating from outside the capital. The ultimate judicial authority laid in hands of the Huey tlatoani, who had the right to appoint lesser judges.[69]

Rulers

| Tenochtitlan | Texcoco | Tlacopan | |

|---|---|---|---|

Huetlatoani

| Cihuacoatl[citation needed]

| Huetlatoani

| Huetlatoani

|

[70][71][72]

See also

- Aztec

- Aztec philosophy

- Flower war

- List of Tenochtitlan rulers

- List of rulers of Texcoco

- List of Tlatelolco rulers

- Mesoamerica

- Nahuas

References

^ ab "El tributo a la Triple Alianza". Arqueología Mexicana. 14 February 2017..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 497. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

^ abc Smith 2009

^ Hassig 1988

^ Smith 2001

^ Smith 2009 pp. 3–4

^ Smith 1984

^ Davies 1973, pp. 3–22

^ Alfredo López Austin, "Aztec" in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Culture, vol. 1, p. 68. Oxford University Press 2001.

^ Smith 2009 p. 37

^ Calnek 1978

^ abc Davies 1973

^ Alvarado Tezozomoc 1975 pp. 49–51

^ Alvarado Tezozomoc (1975), pp. 52–60

^ Smith 2009 p. 44

^ Alvarado Tezozomoc 1975

^ ab Smith 2009 p. 46

^ abcd Smith 2009 p. 47

^ Evans 2008, p. 460

^ The term cihuācōātl literally means "woman-snake" or "female snake", and the origin of this designation is not well understood. The position was certainly not reserved for women, although the title may perhaps suggest a metaphoric dichotomy between the "masculine" Tlahtoāni dealing with external imperial affairs and the "feminine" Cihuācōātl managing the domestic affairs.

^ Leon-Portilla 1963 p. 155

^ ab Smith 2009 p. 48

^ abc Evans 2008 p. 462

^ ab Duran 1994, pp. 209–210

^ Evans 2008 pp. 456–457

^ Evans 2008, p. 451

^ Duran 1994

^ Based on Hassig 1988.

^ Smith 2009 pp. 47–48

^ Smith 2009 p. 49

^ abcd Pollard 1993, p. 169

^ abcde Smith 2009 p. 51

^ Evans 2008, p. 450

^ abcd Smith 2009 p. 54

^ Smith 2009 pp. 50–51

^ Pollard 1993 pp. 169–170

^ Davies 1973 p. 216

^ Diaz del Castillo 2003, pp. 35–40

^ Frances Karttunen, "Rethinking Malinche" in Indian Women of Early Mexico, Susan Schroeder, et al. eds. University of Oklahoma Press 1997.

^ Diaz del Castillo 2003, pp. 92–94

^ Diaz del Castillo 2003, p. 120

^ abcdefgh Hernán Cortés, 1843. The Dispatches of Hernando Cortés, The Conqueror of Mexico, addressed to the Emperor Charles V, written during the conquest, and containing a narrative of its events. New York: Wiley and Putnam

^ abc Smith 2009 p. 275

^ The Early History of Greater Mexico, chapter 3 "Conquest and Colonization", Ida Altman, S.L. (Sarah) Cline, and Javier Pescador. Pearson, 2003.

^ Smith 2009, p. 279

^ Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, Ally of Cortés: Account 13 of the Coming of the Spaniards and the Beginning of Evangelical Law. Douglass K. Ballentine, translator. El Paso: Texas Western Press, 1969.

^ Restall, Matthew (2004). Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest (1st pbk edition ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0-19-517611-1. p. 148

^ Motyl, Alexander J. (2001). Imperial Ends: The Decay, Collapse, and Revival of Empires. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 13, 19–21, 32–36. ISBN 0-231-12110-5.

^ Berdan, et al. (1996), Aztec Imperial Strategies. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC

^ Smith, Michael E. (2000), Aztec City-States. In A Comparative Study of Thirty City-State Cultures, edited by Mogens Herman Hansen, pp. 581–595. The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, Copenhagen.

^

Evans, Susan T. (2004). Ancient Mexico & Central America: Archaeology and Culture History. Thames & Hudson: New York, pp. 443–446, 449–451

^

Coe, Michael D. (1984). Mexico, 3rd Ed. Thames & Hudson: New York, p. 156

^

Townshend, Richard F. (2000). The Aztecs. Revised Ed. Thames & Hudson: London, pp. 200–202.

^ ab

Berdan, Francis F. and Patricia Rieff Anawalt. 1992. The Codex Mendoza Vol. 1. University of California Press, p. 196

^ Brumfiel, Elizabeth M. (1983). Aztec State Making: Ecology, Structure, and the Origin of the State. American Anthropologist, New Series (85)2, p. 273

^ Townshend, Richard F. (2000). The Aztecs. Revised Ed. Thames & Hudson: London, p. 204.

^ Calnek, Edward E. (1982). Patterns of Empire Formation in the Valley of Mexico, in The Inca and Aztec States: 1400–1800. Collier, Rosaldo & Wirth (Eds.) Academic Press: New York, pp. 56–59

^ Smith, Michael E. (1986). Social Stratification in the Aztec Empire: A View from the Provinces, in American Anthropologist,

(88)1, p. 74

^ Kurtz, Donald V. (1984). Strategies of Legitimation and the Aztec State, in Ethnology, 23(4), pp. 308–309

^ Almazán, Marco A. (1999). The Aztec States-Society: The Roots of Civil Society and Social Capital, in Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 565, p. 170.

^ Brumfiel, Elizabeth M. (2001). Religion and state in the Aztec Empire, in Empires (Alcock et al, Eds). Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, p. 284

^ ab Evans, pp. 470–471

^ ab Smith, Michael E. (1996). The Strategic Provinces, in Aztec Imperial Strategies. Dumbarton Oaks: Washington, D.C., pp. 1–2

^ Almazán, pp. 165–166

^ Brumfiel (2001), pp. 287, 288–301

^ León-Portilla, Miguel. (1963). Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the ANcient Nahuatl Mind. Davis, Jack E., Trans. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, pp. 6, 161–162

^ Offner, Jerome A. Law and Politics in Aztec Texcoco. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1983, pp.81-82.

^ Offner, 1983, p. 83

^ Kurtz, p. 307

^ Coe, p. 170

^ Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin. (1997). Codex Chimalpahin, Vol. 1. University of Oklahoma Press: Norman.

^ Tlacopan. Updated March, 20120. Retrieved from http://members.iinet.net.au/~royalty/states/southamerica/tlacopan.html.

Bibliography

Library resources about Aztec Empire |

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aztec. |

Primary sources

Berdan, Frances F.; Anawalt, Patricia Rieff (1997). The Essential Codex Mendoza. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20454-6.

Diaz del Castillo, Bernal, The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico (1576), Cambridge, MA, Da Capo Press, 2003.

ISBN 0-306-81319-X.

Durán, Diego, History of the Indies of New Spain (c. 1581), University of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

Alvarado Tezozomoc, Hernando, Crónica Mexicana (c. 1598), Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, 1978.

Secondary sources

Calnek, Edward (1978). R. P. Schaedel; J. E. Hardoy; N. S. Kinzer, eds. Urbanization of the Americas from its Beginnings to the Present. pp. 463–470.

Davies, Nigel (1973). The Aztecs: A History. University of Oklahoma Press.

Evans, Susan T. (2008). Ancient Mexico and Central America: Archaeology and Culture History, 2nd edition. Thames & Hudson, New York. ISBN 978-0-500-28714-9.

Hassig, Ross (1988). Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2121-1.

Leon-Portilla, Miguel (1963). Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Náhuatl Mind. University of Oklahoma Press.

Pollard, H. P. (1993). Tariacuri's Legacy. University of Oklahoma Press.

Smith, Michael (1984). "The Aztec Migrations of Nahuatl Chronicles: Myth or History?". Ethnohistory. 31 (3): 153–168. doi:10.2307/482619.

Smith, Michael (2009). The Aztecs, 2nd Edition. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23015-7.

Smith, M. E. (2001). "The Archaeological Study of Empires and Imperialism in Pre-Hispanic Central Mexico". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 20: 245–284. doi:10.1006/jaar.2000.0372.

Soustelle, Jacques, The Daily Life of the Aztecs. Paris, 1955; English edition, 1964.