Micrometeoroid

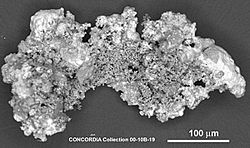

Micrometeorite, collected from the Antarctic snow, was a micrometeoroid before it entered the Earth's atmosphere

A micrometeoroid is a tiny meteoroid; a small particle of rock in space, usually weighing less than a gram. A micrometeorite is such a particle that survives passage through the Earth's atmosphere and reaches the Earth's surface.

Contents

1 Scientific interest

2 Effect on spacecraft operations

3 Footnotes

4 See also

5 External links

Scientific interest

Lunar sample 61195 from Apollo 16 textured with "zap pits" from micrometeorite impacts.

Micrometeoroids are very small pieces of rock or metal broken off from larger chunks of rock and debris often dating back to the birth of the Solar System. Micrometeoroids are extremely common in space. Tiny particles are a major contributor to space weathering processes. When they hit the surface of the Moon, or any airless body (Mercury, the asteroids, etc.), the resulting melting and vaporization causes darkening and other optical changes in the regolith. In order to understand the micrometeoroid population better, a number of spacecraft (including Lunar Orbiter 1, Luna 3, Mars 1 and Pioneer 5) have carried micrometeoroid detectors.

In 1957 Hans Peterson conducted one of the first direct measurements of the fall of space dust on the Earth, estimating it to be 14,300,000 tons per year.[1] If this were true, then the Moon would be covered to a very great depth as there are limited forms of erosion to remove this material. In 1961 Arthur C. Clarke popularized this possibility in his novel A Fall of Moondust. This was cause for some concern among the groups attempting to land on the Moon, so a series of new studies followed to better characterize the issue. This included the launch of several spacecraft designed to directly measure the micrometeorite flux (Pegasus satellite program) or directly measure the dust on the surface of the Moon (Surveyor Program). These showed that the flux was much lower than earlier estimates, around 10,000 to 20,000 tons per year, and that the surface of the Moon is relatively rocky.[2] Most lunar samples returned during the Apollo Program have micrometeorite impacts marks, typically called "zap pits", on their upper surfaces.[3]

Micrometeoroids have less stable orbits than meteoroids, due to their greater surface area to mass ratio. Micrometeoroids that fall to Earth can provide information on millimeter scale heating events in the solar nebula. Meteorites and micrometeorites (as they are known upon arrival at the Earth's surface) can only be collected in areas where there is no terrestrial sedimentation, typically polar regions. Ice is collected and then melted and filtered so the micrometeorites can be extracted under a microscope.

Sufficiently small micrometeoroids avoid significant heating on entry into the Earth's atmosphere.[4] Collection of such particles by high flying aircraft began in the 1970s,[5] since which time these samples of stratosphere-collected interplanetary dust (called Brownlee particles before their extraterrestrial origin was confirmed) have become an important component of the extraterrestrial materials available for study in laboratories on Earth.

Effect on spacecraft operations

Electron micrograph image of an orbital debris hole made in the panel of the Solar Max satellite.

Micrometeoroids pose a significant threat to space exploration. The average velocity of micrometeoroids relative to a spacecraft in orbit is 10 kilometers per second (22,500 mph). Resistance to micrometeoroid impact is a significant design challenge for spacecraft and space suit designers (See Thermal Micrometeoroid Garment). While the tiny sizes of most micrometeoroids limits the damage incurred, the high velocity impacts will constantly degrade the outer casing of spacecraft in a manner analogous to sandblasting. Long term exposure can threaten the functionality of spacecraft systems.[6]

Impacts by small objects with extremely high velocity (10 kilometers per second) are a current area of research in terminal ballistics. (Accelerating objects up to such velocities is difficult; current techniques include linear motors and shaped charges.) The risk is especially high for objects in space for long periods of time, such as satellites.[6] They also pose major engineering challenges in theoretical low-cost lift systems such as rotovators, space elevators, and orbital airships.[7][8]

Footnotes

^ Pettersson, Hans. "Cosmic Spherules and Meteoritic Dust." Scientific American, Volume 202 Issue 2, February 1960, pp. 123–132.

^ Snelling, Andrew and David Rush. "Moon Dust and the Age of the Solar System." Creation Ex-Nihilo Technical Journal, Volume 7, Number 1, 1993, p. 2–42.

^ Wilhelms, Don E., To a Rocky Moon: A Geologist's History of Lunar Exploration (PDF), University of Arizona Press, p. 97, ISBN 978-0816510658.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ P. Fraundorf (1980) The distribution of temperature maxima for micrometeorites decelerated in the Earth's atmosphere without melting Geophys. Res. Lett. 10:765-768.

^ D. E. Brownlee, D. A. Tomandl and E. Olszewski (1977) Interplanetary dust: A new source of extraterrestrial material for laboratory studies, Proc. Lunar Sci. Conf. 8th:149-160.

^ ab Rodriguez, Karen (April 26, 2010). "Micrometeoroids and Orbital Debris (MMOD)". www.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

^ Swan, Raitt, Swan, Penny, Knapman, Peter A., David I., Cathy W., Robert E., John M. (2013). Space Elevators: An Assessment of the Technological Feasibility and the Way Forward. Virginia, USA: International Academy of Astronautics. pp. 10–11, 207–208. ISBN 9782917761311.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

^ Swan, P., Penny, R. Swan, C. Space Elevator Survivability, Space Debris Mitigation, Lulu.com Publishers, 2011

See also

- Extraterrestrial materials

- Interplanetary dust cloud

External links

Melted Crumbs from Asteroid Vesta article about micrometeorites collected in Antarctica in Planetary Science Research Discoveries educational journal