CalgaryNEXT

CalgaryNEXT Location in Calgary Show map of Calgary  CalgaryNEXT Location in Quebec Show map of Alberta  CalgaryNEXT Location in Canada Show map of Canada | |

| Location | Calgary, Alberta |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°02′49″N 114°06′21″W / 51.04694°N 114.10583°W / 51.04694; -114.10583Coordinates: 51°02′49″N 114°06′21″W / 51.04694°N 114.10583°W / 51.04694; -114.10583 |

| Public transit | Calgary Transit Sunalta LRT station |

| Owner | City of Calgary (Proposed) |

| Operator | Calgary Sports and Entertainment Corporation N. Murray Edwards Alvin Libin Allan Markin Jeffrey McCaig Clay Riddell Byron Seaman |

| Capacity | 19,000 (Events Centre; Projected) 41,000 (Stadium; Projected) |

| Construction | |

| Construction cost | $890 million (Projected as of August 2015)[1] $1.8 billion (Projected as of April 2016)[2] |

| Tenants | |

Proposed: Calgary Flames (NHL) (Events Centre) Calgary Hitmen (WHL) (Events Centre) Calgary Roughnecks (NLL) (Events Centre) Calgary Stampeders (CFL) (Stadium) | |

CalgaryNEXT is a proposed private-public multi-purpose 365-day-a-year sports complex[1] to be built in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. It would replace the Scotiabank Saddledome (one of the oldest arenas in the NHL) and McMahon Stadium for Calgary's professional hockey and Canadian football teams.

The proposal includes two buildings: a 19,000–20,000 seat events centre[1] that would serve as the home arena of two hockey clubs, the National Hockey League's Calgary Flames, and the Calgary Hitmen of the Western Hockey League,[3] as well as the Calgary Roughnecks lacrosse team; and a 30,000-seat football stadium and fieldhouse[1] that would be the home of the Canadian Football League's Calgary Stampeders and serve as a public training and activity space. The complex, to be located in the West Village along the Bow River[1][4] for the "hub of pro and amateur sporting activity."[1]

Immediate reaction to the proposal from local politicians was mixed; they supported the plan to redevelop the West Village area, but many – including Mayor Naheed Nenshi – expressed concern at the proposal,[5] which would potentially have the city initially fund between $440 and $690 million of the projected cost which promoters claim will be recouped over a long period of time. As part of the proposal, the city would own the facilities and be managed by the privately owned Calgary Sports and Entertainment Corporation (CSEC) - thus exempting the land from property taxes - but would not receive any share of the profits.

Originally projected as costing $890 million,[1][4] based on a City of Calgary report released April 2016 it was estimated that CalgaryNEXT would cost about $1.8 billion, with taxpayers paying up to two-thirds of the total.[2][6]

Contents

1 Private-public partnership

2 Facilities

2.1 Events Centre

2.2 Fieldhouse and stadium

3 Financing

3.1 Community Revitalization Levy, Tax Incremental Financing

3.2 Ticket surcharge

4 Timeline

5 Debate

6 Proposed location

6.1 Creosote-contamination site

6.2 Floodplain concerns

7 References

Private-public partnership

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

It’s also important to note that at least two of the six Flames owners are billionaires (and three are among the wealthiest 100 individuals on Canada)...I’m sure the other 3 aren’t that far off. They need taxpayer help.

— Josh White, City of Calgary Policy Analyst January 2013.

In June 2014, after Flames executive Brian Burke announced plans to replace the 31-year-old Scotiabank Saddledome that would require public financial investment, Calgary city councillors received 199 emails opposing a public subsidy for an arena and one in support.[7] The wealth of Markin, Libin, McCaig, Seaman, Edwards and Riddell - the six men who co-own the Calgary Sports and Entertainment Corporation, a profitable private entity, that is also the parent group of the Flames, Stampeders, Hitmen, and Roughnecks, "often played a role in residents’ strident letters to councillors about potential taxpayer support."[7] Edwards and Riddel alone "have a combined fortune of $4.8 billion according to Forbes."[3]

According to the CSEC, who unveiled their megaproject in August 2015 during a period when slumping oil prices and layoffs in the energy sector were leading Alberta into a recession,[8] CalgaryNEXT would provide a much needed economic stimulus.[9] CSEC owners - Allan Markin, Alvin Libin, Jeffrey McCaig, Byron Seaman as well as billionaires[7][3]Murray Edwards and Clay Riddell,[10] include some of Calgary’s wealthiest oilmen.[9]

CSEC had proposed to pay $200 million of the cost directly, have the city pay $200 million to fund the field house,[11] and the remainder funded by a ticket surcharge on events at the new facilities, and a community revitalization levy. Environmental remediation required to clean up creosote contamination on the site, would provide an additional cost to the project.

Facilities

Calgary Sports and Entertainment Corporation proposed the new complex to replace the city's two primary sporting venues, each of which is among the oldest in the league of its respective primary tenant: McMahon Stadium, a dual purpose Canadian football and soccer venue, opened in 1960, while the Scotiabank Saddledome, Calgary's main indoor arena, opened in 1983.[12]

The Calgary Flames, Calgary Stampeders, Western Hockey League’s Hitmen and National Lacrosse League’s Roughnecks are all owned by Calgary Sports and Entertainment Corporation. CSEC's roots are in a partnership of Calgary oil executives who bought the then-Atlanta Flames and moved them to Calgary in 1980. The partnership bought the Hitmen in 1997. It was reorganized as CSEC in 2010, and bought the Roughnecks in 2011 and the Stampeders a year later.

CSEC CEO, Ken King was quoted as saying,[1]

You don’t replace things because they’re old....You replace things because they’re not efficient and they’re not functional and they’re not doing the job that they were originally designed and intended to do.

— Ken King Calgary Sun August 18, 2015

Although just over 30 years old, the Saddledome is one of the oldest venues in the NHL,[1] while McMahon Stadium is considered among the worst facilities in the Canadian Football League.[13]

The CalgaryNEXT development would consist of two facilities with a shared atrium. It is proposed for the West Village on the west end of Downtown Calgary, and located along the Bow River.[14] CSEC had looked at other locations within the city, including Stampede Park, where the Saddledome and the Stampede Corral are located before determining that the park could not support the size of the proposed complex.[15]

Events Centre

The Events Centre would replace the Saddledome as the city's primary indoor arena and become the home of the Calgary Flames (National Hockey League), Calgary Hitmen (Western Hockey League) and Calgary Roughnecks (National Lacrosse League).[15] CSEC proposed that the Events Centre would have a seating capacity between 19,000 and 20,000.[16]

Fieldhouse and stadium

In April, 2013, Calgary's community and protective services committee approved the location of an "indoor multisport complex in the northwest, at Foothills Athletic Park at University Drive and 24th Avenue N.W. At that time it was noted by Donna Dixon, then head of the Calgary Multisport Fieldhouse Society, that even though there was a lot of support from the city, council and administration to look very hard at trying to find funding sources... the time frame is probably still five years out, because the funding hasn't been found yet.[17] After the decision was made to prioritize the building of the Fieldhouse, Alderman Brian Pincott commented, "Putting the fieldhouse first means we're going to have to find a great gob of money for that first. You need to find $200 million."[17]

In the 2015 CalgaryNext proposal the fieldhouse—a "hub of pro and amateur sporting activity"—would be located in the West Village along the Bow River[1][4][1] The second facility would be a combination Canadian Football stadium that would seat 30,000-50,000 spectators and public fieldhouse that would be constructed to also meet FIFA standards for soccer and would include a 400-metre indoor running track, volleyball, basketball, tennis and badminton courts.[16] It is proposed to be a fixed-roof facility with a partially translucent roof to allow for natural sunlight.[12]

Financing

In August 2015, CSEC estimated the cost of construction would total $890 million[1][4] and proposed four funding sources: The organization would fund $200 million of its own funds, while the city would also provide $200 million to fund the field house. $240 million would be funded via the city's Community Revitalization Levy program, and $250 million would be through a ticket surcharge on events held at the two facilities; CSEC's CEO Ken King stated on the project's announcement that the initial funding source that the ticket surcharge would repay had not been determined, but suggested that loans by the City or from conventional commercial lenders were both possibilities.[16] In a written statement, Mayor Naheed Nenshi called the proposal "intriguing", but reiterated his personal opposition to the use of public funds for private profit, and noted that the city has already allocated its available capital funds through the 2018 budget cycle.[18] As part of the proposal, the city would own the facilities and be managed by CSEC.[19]

Community Revitalization Levy, Tax Incremental Financing

In an interview with the Calgary Sun in February 2015, Michael Brown, president and CEO of the Calgary Municipal Land Corporporation (CMLC), an arms-length organization that handles Calgary's land holdings, said they were looking into the Community Revitalization Levy (CRL)— a Tax Incremental Financing (TIF) system[20] widely used in the United States — [21] for the development of the West Village similar to that used to finance the remediation of the East Village. The East Village CRL benefited from the Bow as an anchor building for the revitalization.[21] Though supportive of the CalgaryNEXT project in principle, several local politicians expressed concern about the funding model, which proposed that the city would front between $440 and $690 million of the projected cost, most which would only be recouped over a long period of time if at all.[22] By August 2015 the total projected cost of CalgaryNEXT was $890-million.[1][4] Nenshi commented that one of a number of challenges to the CalgaryNEXT proposal was the requirement of a community revitalization levy, along with the need for a land contribution from the City, "and significant investments in infrastructure to make the West Village a complete and vibrant community."[5]

According to a majority of city councillors, using a Community Revitalization Levy for CalgaryNEXT, would not generate any property tax because it would be a city-owned building.[23][2]

By December 2015, while King maintained the $890-million project "could generate as much as $900 million in ancillary property tax revenue, in part through the use of the $240-million revitalization levy", Nenshi disagreed "saying the success of the levy in that location is intimately tied to the cost of remediating the land."[23]

The early numbers that I’ve seen, and this was before we really did in-depth analysis which is being done right now, indicate that it doesn’t balance... The (levy) doesn’t even raise enough to cover the cost of clean up let alone put $200 or $300 million into an arena...I’ve never heard anyone say anything close to $900 million with any credibility behind it.

— Mayor Nenshi December 30, 2015 Calgary Herald

The land corporation’s 2016 analysis estimated that the levy would generate, "at most, $430 million over 20 years if it could secure an anchor tenant in a 700,000-square-foot building. Without a tenant, the levy would only generate $350 million over the same period."[2]

Ticket surcharge

One funding source would be a ticket surcharge on events held at the CalgaryNEXT facilities.[16]

Timeline

WorleyParsons was hired by the Calgary City Hall[4] and the Calgary Municipal Land Corporation to examine the CSEC proposal, and to conduct a six-month economic and environmental assessment study in the West Village with a report due April 30, 2016. They will assess the scale of contamination in the area" and the cost of an "environmental cleanup and analysis of potential revenue from a levy."[23]

In August 2015, King told reporters he would like to have the CalgaryNEXT operational for the NHL campaign in 2020-2021.[1]

Debate

During a high-profile sold-out downtown Calgary luncheon meeting held January 11, 2016 and attended by Calgary's community leaders, business elite, Flames CEO Ken King, city officials and representatives from the mayor's office - but not Mayor Nenshi or councillors - the New York-based NHL commissioner Gary Bettman "delivered an aggressive sales pitch" calling on Calgary to "embrace" the $890-million CalgaryNEXT proposal or deal with the consequences."[4] and expressed his impatience with the city for not moving ahead with the project.[24]

"It is not an overstatement to say the future tability, viability and continuity of the Calgary Flames, and perhaps the city of Calgary, rests on the achievement of CalgaryNEXT.

— Gary Bettman January 11, 2016 Calgary Herald

After his speech to Calgary's Chamber of Commerce, Bettman reasserted,[10]

If this project is going to happen, the mayor needs to embrace it, the city needs to embrace it... If he’s not prepared to embrace it, then the people will have to deal with that.

— Gary Bettman January 11, 2016

Mayor Nenshi responded to Bettman's comments,

In other cities these sorts of deals are presented to the public as a fait accompli with a gift wrapped ribbon on them...That is not how we’ve chosen to operate, that’s not how council in public unanimously decided to move forward.

— Mayor Nenshi January 11, 2016 Calgary Herald

In December 2016, Mayor Nenshi explained that City of Calgary's bid package for the 2026 Olympics, could not include CalgaryNEXT as some supporters had hoped, as the International Olympic Committee (IOC) agenda 2020, which lays out the rules for bidding, "discourage[s] the building of new infrastructure"[6] and "give[s] credit to cities who have existing sports venues that would only require minimal upgrades to make them 'Olympics-ready.'"[25]

Proposed location

The proposed site for CalgaryNEXT was used by the Domtar-owned and operated Creosote Canada plant from 1924 until 1962. For decades chemicals leached deep and wide into the ground.[26] According to the City of Calgary's website,[27]

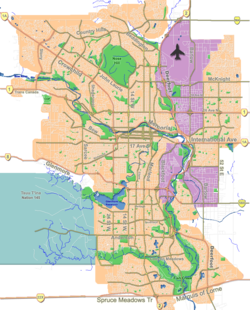

The West Village is a 130 acre area immediately west of Calgary’s downtown. The boundaries are the Bow River to the north, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) right-of-way to the south, Crowchild Trail S.W. to the west, and 14th Street S.W. to the east.

— City of Calgary

As of early 2018, the land contained within these boundaries contains the city's Greyhound Canada bus terminal, several automobile dealerships, Pumphouse Theatre (a live performance venue located within a converted historic municipal utility building) and parkland. Bow Trail, a major commuter route into and out of the downtown core, passes through the middle of the property.

The City of Calgary purchased the 4.2-ha parcel of land in November 2014 for $36.9 million[28] in order for the City and Province to protect the environment and ensure public safety given the level of environmental contamination of the site. Mitigation has included a 1995-96 provincially-funded containment wall and later on a containment system for the contamination. In 2010 the City approved the West Village Area Redevelopment Plan which along with the West LRT project required the acquisition of additional land.[27]

Creosote-contamination site

Councillor Evan Woolley estimated that the environmental remediation of this site would cost much more than remediation for the "East Village, which cost in the hundreds of millions."[28] The costs of the clean-up is not presently known, but estimated between $50 and $300 million.[12][23]

Floodplain concerns

In an interview with a Calgary Herald journalist, Professor John Pomeroy, Canada Research Chair in Water Resources and Climate Change, expressed shock that two years after massive flooding, the only location proposed for CalgaryNEXT is on the floodplain. He argued that this area will be flooded in the future.[29] Gian-Carlo Carra, City councillor, who represents the inner city in Ward 9, expressed his aggravation at the promotion of green spaces and parks in the floodplain. Carra would prefer to see tax-generating development in the floodplains.[30] In January 2015, Alberta WaterSmart, an engineering consulting published the report entitled Room for the River commissioned by the Province of Alberta. Kim Sturgess, chief executive of Alberta WaterSmart, agreed with Pomeroy that there will be a flooding event and it is a matter of how much risk the Flames organization is willing to take on.[31] In her report Sturgess recommended "revisiting property buyouts, preventing future floodplain development and widening riverbanks" to mitigate future floods and manage watersheds."[31] In an interview with the Herald, Calgary Flames president Ken King "acknowledged they are considering potential flooding as part of the building’s design." He said that the proposed location on the Bow River is "far less problematic than where we are now, but nothing is immune."[29]

References

^ abcdefghijklmn Wes Gilbertson (18 August 2015). "No question Calgary pro sports venues are out-of-date". Calgary Sun. Retrieved 27 August 2015..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcd Howell, Trevor (21 April 2016). "Flames' CalgaryNEXT proposal could cost $1.8 billion, double original estimate, says city report". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

^ abc Lambert, Taylor (19 August 2015). "New Calgary arena proposal nothing short of brazen". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

^ abcdefg Howell, Trevor (12 January 2016). "War of words over Flames' CalgaryNEXT proposal not 'useful,' says city manager". Calgary Herald of the Postmedia Network. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

^ ab "Statement from Mayor Naheed Nenshi regarding the "CalgaryNext"". Office of the Mayor, City of Calgary. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

^ ab Pike, Helen (December 23, 2016), "Using CalgaryNEXT as part of Olympic bid detrimental to city's chances: Nenshi", Metro, retrieved December 23, 2016

^ abc Markusoff, Jason (4 December 2014). "Arena debate: Why it matters that the Flames owners are billionaires, and why it doesn't". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

^ Hudes, Sammy (26 August 2015). "NDP won't make mass cuts to public service, Notley vows". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

^ ab Cattaneo, Claudia (17 August 2015). "Calgary sports complex plan brings government, oil to same table". Financial Post. Calgary Herald. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

^ ab Ewart, Stephen (13 January 2016). "Ewart: As Harper was to Keystone XL, Bettman is to CalgaryNEXT". Calgary Herald of the Postmedia Network. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

^ Klingbeil, Annalise (August 18, 2015). "Flames reveal details of $890M downtown arena-stadium plan". Calgary Herald. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

^ abc "CalgaryNEXT: A vision for the future". Calgary Herald. August 19, 2015. p. A5.

^ [1]

^ Klingbiel, Annalise; Howell, Trevor (2015-08-19). "Flames reveal proposal details". Calgary Herald. p. A3.

^ ab Toneguzzi, Mario (August 19, 2015). "Flames' aspirations were just too big for Stampede Park". Calgary Herald. p. A6. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

^ abcd Dormer, Dave (August 19, 2015). "Next Big Thing". Calgary Sun. p. 4. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

^ ab "Fieldhouse plan for Foothills park clears hurdle: $200M indoor multisport complex for northwest Calgary still not funded". CBC News. April 4, 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

^ "Calgary Flames announce plan for $900M arena complex". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. August 18, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

^ Braid, Don (2015-08-19). "Grand plan shrouded in mystery". Calgary Herald. p. A2.

^ Bakx, Kyle (22 May 2015). "Risky business as Canadian cities turn to neighbourhood levies: Expert warns the levies can be 'direct subsidies for the developers'". CBC. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

^ ab James Wilt (10 January 2013). "Blighted streets, no more". Fast Forward Weekly. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

[permanent dead link]

^ Johnson, George (2015-08-19). "Let King begin the courtship". Calgary Herald. p. C1.

^ abcd Howell, Trevor (30 December 2015). "Early analysis suggests arena levy wouldn't work as advertised, says Nenshi". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

^ "The National". CBC. 11 January 2016.

^ Bascaramurty, Dakshana (July 3, 2015). "Glamour, pride and cash: Why cities compete to put on a sports spectacle". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

^ Dave Dormer (19 August 2015). "West Village creosote: What is it and who's to blame?". Calgary Sun. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

^ ab "City Response to Questions about West Village". City of Calgary. 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

[permanent dead link]

^ ab Dave Dormer (28 February 2015). "Calgary officials have work cut out transforming west end of downtown into West Village". Calgary Sun. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

^ ab Colette Derworiz (24 August 2015). "Water expert astonished by proposed location of CalgaryNEXT along Bow River". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

^ Colette Derworiz (24 August 2015). "City councillor aggravated by CalgaryNEXT floodplain concerns". Calgary, Alberta: Calgary Herald. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

^ ab Colette Derworiz (January 12, 2015). "Room for the river report moves focus beyond big infrastructure". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 26 August 2015.