Role of Christianity in civilization

Disputa by Italian Renaissance artist Raphael

| Part of a series on |

| Christian culture |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Christianity portal |

The role of Christianity in civilization has been intricately intertwined with the history and formation of Western society. Throughout its long history, the Church has been a major source of social services like schooling and medical care; inspiration for art, culture and philosophy; and influential player in politics and religion. In various ways it has sought to affect Western attitudes to vice and virtue in diverse fields. Festivals like Easter and Christmas are marked as public holidays; the Gregorian Calendar has been adopted internationally as the civil calendar; and the calendar itself is measured from the date of Jesus's birth.

The cultural influence of the Church has been vast. Church scholars preserved literacy in Western Europe following the Fall of the Western Roman Empire.[1] During the Middle Ages, the Church rose to replace the Roman Empire as the unifying force in Europe. The cathedrals of that age remain among the most iconic feats of architecture produced by Western civilization. Many of Europe's universities were also founded by the church at that time. Many historians state that universities and cathedral schools were a continuation of the interest in learning promoted by monasteries.[2] The university is generally regarded[3][4] as an institution that has its origin in the Medieval Christian setting, born from Cathedral schools.[5] The Reformation brought an end to religious unity in the West, but the Renaissance masterpieces produced by Catholic artists like Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael at that time remain among the most celebrated works of art ever produced. Similarly, Christian sacred music by composers like Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Handel, Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Liszt, and Verdi is among the most admired classical music in the Western canon.

The Bible and Christian theology have also strongly influenced Western philosophers and political activists. The teachings of Jesus, such as the Parable of the Good Samaritan, are among the important sources for modern notions of Human Rights and the welfare measures commonly provided by governments in the West. Long held Christian teachings on sexuality and marriage and family life have also been both influential and (in recent times) controversial. Christianity played a role in ending practices such as human sacrifice, slavery,[6] infanticide and polygamy.[7] Christianity in general affected the status of women by condemning marital infidelity, divorce, incest, polygamy, birth control, infanticide (female infants were more likely to be killed), and abortion.[8] While official Church teaching[9] considers women and men to be complementary (equal and different), some modern "advocates of ordination of women and other feminists" argue that teachings attributed to St. Paul and those of the Fathers of the Church and Scholastic theologians advanced the notion of a divinely ordained female inferiority.[10] Nevertheless, women have played prominent roles in Western history through and as part of the church, particularly in education and healthcare, but also as influential theologians and mystics.

Christians have made a myriad contributions to human progress in a broad and diverse range of fields, both historically and in modern times, including the science and technology,[11][12][13][14][15]medicine,[16]fine arts and architecture,[17][18][19] politics, literatures,[19]Music,[19]philanthropy, philosophy,[20][21][22]:15ethics,[23]theatre and business.[24][25][18][26] According to 100 Years of Nobel Prizes a review of Nobel prizes award between 1901 and 2000 reveals that (65.4%) of Nobel Prizes Laureates, have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference.[27]Eastern Christians (particularly Nestorian Christians) have also contributed to the Arab Islamic Civilization during the Ummayad and the Abbasid periods by translating works of Greek philosophers to Syriac and afterwards to Arabic.[28][29][30] They also excelled in philosophy, science, theology and medicine.[31][32]

Some of the things that Christianity is commonly criticized for include the oppression of women, condemnation of homosexuality, colonialism, and various other cases of violence. Christian ideas have been used both to support and to end slavery as an institution. The criticism of Christianity has come from the various religious and non-religious groups around the world, some of whom were themselves Christians.

Contents

1 Politics and law

1.1 From persecuted minority to State Religion

1.1.1 Human value

1.1.1.1 Women

1.1.1.2 Children

1.1.2 Constantine

1.1.3 Fourth Century

1.1.4 The Fall of Rome

1.1.4.1 The Dark Ages

1.2 Medieval period

1.2.1 Early Middle Ages

1.2.2 High Middle Ages

1.2.2.1 Inquisition

1.2.3 Late Middle Ages

1.2.3.1 Women

1.2.3.2 The Popes

1.2.4 Crusade

1.2.5 Human Rights

1.3 Reformation until Modern era

2 Sexual morals

3 Marriage and family life

3.1 Roman Empire

3.2 Medieval period

4 Slavery

4.1 Latin America

4.2 Africa

5 Letters and learning

5.1 Antiquity

5.2 Byzantine Empire

5.3 Preservation of Classical learning

5.4 Index Librorum Prohibitorum

5.5 Protestant role in science

5.6 Astronomy

5.7 Evolution

5.8 Embryonic stem cell research

6 Art, architecture, literature, and music

7 Economic development

7.1 Protestant work ethic

8 Social justice, care-giving, and the hospital system

8.1 Fourth Century

8.2 Medieval period

8.3 Industrial Revolution

9 Education

9.1 Europe

9.2 Latin America

9.3 North America

9.4 Australasia

9.5 Africa

9.6 Asia

9.7 Protestant role in education

10 See also

11 References

12 Bibliography

Politics and law

From persecuted minority to State Religion

Icon depicting the Roman Emperor Constantine (centre) and the bishops of the First Council of Nicaea (325) holding the Niceno–Constantinopolitan Creed of 381.

Christianity began as a Jewish sect in the mid-1st century arising out of the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. The life of Jesus is recounted in the New Testament of the Bible, one of the bedrock texts of Western Civilization and inspiration for countless works of Western art.[33] Jesus' birth is commemorated in the festival of Christmas, his death during the Paschal Triduum, and what Christians believe to be his resurrection during Easter. Christmas and Easter remain holidays in many Western nations. Jesus learned the texts of the Hebrew Bible, with its Ten Commandments (which later became influential in Western law) and became an influential wandering preacher. He was a persuasive teller of parables and moral philosopher who urged followers to worship God, act without violence or prejudice and care for the sick, hungry and poor. These teachings have been deeply influential in Western culture. Jesus criticized the privilege and hypocrisy of the religious establishment which drew the ire of the authorities, who persuaded the Roman Governor of the province of Judaea, Pontius Pilate, to have him executed. The Tanakh says Jesus was executed for sorcery and for leading the people into apostacy.[34] In Jerusalem, around 30AD, Jesus was crucified.[35]

The early followers of Jesus, including Saints Paul and Peter carried this new theology concerning Jesus throughout the Roman Empire and beyond, sowing the seeds for the development of the Catholic Church, of which Saint Peter is remembered as the first Pope. Catholicism, as we know it, emerged slowly. Christians often faced persecution during these early centuries, particularly for their refusal to join in worshiping the emperors. Nevertheless, carried through the synagogues, merchants and missionaries across the known world, the new internationalist religion quickly grew in size and influence.[35] It's unique appeal was partly the result of its values and ethics.[36]

Human value

The world's first civilizations were Mesopotamian sacred states ruled in the name of a divinity or by rulers who were themselves seen as divine. Rulers, and the priests, soldiers and bureaucrats who carried out their will, were a small minority who kept power by exploiting the many.[37]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

If we turn to the roots of our western tradition, we find that in Greek and Roman times not all human life was regarded as inviolable and worthy of protection. Slaves and 'barbarians' did not have a full right to life and human sacrifices and gladiatorial combat were acceptable... Spartan Law required that deformed infants be put to death; for Plato, infanticide is one of the regular institutions of the ideal State; Aristotle regards abortion as a desirable option; and the Stoic philosopher Seneca writes unapologetically: "Unnatural progeny we destroy; we drown even children who at birth are weakly and abnormal... And whilst there were deviations from these views..., it is probably correct to say that such practices...were less proscribed in ancient times. Most historians of western morals agree that the rise of ...Christianity contributed greatly to the general feeling that human life is valuable and worthy of respect.[38]

W.E.H.Lecky gives the now classical account of the sanctity of human life in his history of European morals saying Christianity "formed a new standard, higher than any which then existed in the world..."[39] Christian ethicist David P. Gushee says "The justice teachings of Jesus are closely related to a commitment to life's sanctity..."[40]

John Keown, a professor of Christian ethics distinguishes this 'sanctity of life' doctrine from "a quality of life approach, which recognizes only instrumental value in human life, and a vitalistic approach, which regards life as an absolute moral value... [Kewon says it is the] sanctity of life approach ... which embeds a presumption in favor of preserving life, but concedes that there are circumstances in which life should not be preserved at all costs", and it is this which provides the solid foundation for law concerning end of life issues.[41]

Women

Rome had a social caste system, with women having "no legal independence and no independent property."[42] Early Christianity, as Pliny the Younger explains in his letters to Emperor Trajan, had people from "every age and rank, and both sexes."[43] Pliny reports arresting two slave women who claimed to be 'deaconesses' in the first decade of the second century.[44] There was a rite for the ordination of women deacons in the Roman Pontifical, (a liturgical book), up through the 12th century. For women deacons, the oldest rite in the West comes from an eighth-century book, whereas Eastern rites go all the way back to the third century and there are more of them.[45]

The New Testament refers to a number of women in Jesus’ inner circle. There are several Gospel accounts of Jesus imparting important teachings to and about women: his meeting with the Samaritan woman at the well, his anointing by Mary of Bethany, his public admiration for a poor widow who donated two copper coins to the Temple in Jerusalem, his stepping to the aid of the woman accused of adultery, his friendship with Mary and Martha the sisters of Lazarus, and the presence of Mary Magdalene, his mother, and the other women as he was crucified. Historian Geoffrey Blainey concludes that "as the standing of women was not high in Palestine, Jesus' kindnesses towards them were not always approved by those who strictly upheld tradition."[46]

According to Christian apologist Tim Keller, it was common in the Greco-Roman world to expose female infants because of the low status of women in society. The church forbade its members to do so. Greco-Roman society saw no value in an unmarried woman, and therefore it was illegal for a widow to go more than two years without remarrying. Christianity did not force widows to marry and supported them financially. Pagan widows lost all control of their husband's estate when they remarried, but the church allowed widows to maintain their husband's estate. Christians did not believe in cohabitation. If a Christian man wanted to live with a woman, the church required marriage, and this gave women legal rights and far greater security. Finally, the pagan double standard of allowing married men to have extramarital sex and mistresses was forbidden. Jesus' teachings on divorce and Paul's advocacy of monogamy began the process of elevating the status of women so that Christian women tended to enjoy greater security and equality than did women in surrounding cultures.[47]

Children

In the ancient world infanticide was not legal but was rarely prosecuted. A broad distinction was popularly made between infanticide and infant exposure which was practiced on a gigantic scale with impunity. Many exposed children died, but many were taken by speculators who raised them to be slaves or prostitutes. It is not possible to ascertain, with any degree of accuracy, what diminution of infanticide resulted from legal efforts against it in the Roman empire. "It may, however, be safely asserted that the publicity of the trade in exposed children became impossible under the influence of Christianity, and that the sense of the seriousness of the crime was very considerably increased."[39]:31,32

Constantine

Emperor Constantine's Edict of Milan in 313 AD ended the state sponsored persecution of Christians in the East and his own conversion to Christianity was a significant turning point in history.[48] In 312, Constantine offered civic toleration to Christians, and through his reign instigated laws and policies in keeping with Christian principles – making Sunday the Sabbath "day of rest" for Roman society (though initially this was only for urban dwellers) and embarking on a church building program. In AD 325, Constantine conferred the First Council of Nicaea to gain consensus and unity within Christianity, with a view to establishing it as the religion of the Empire. The population and wealth of the Roman Empire had been shifting east, and around the year 330, Constantine established the city of Constantinople as a new imperial city which would be the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Eastern Patriarch in Constantinople now came to rival the Pope in Rome and Rome itself was sacked by the Visigoths in 410 and the Vandals in 455. Although cultural continuity and interchange would continue between these Eastern and Western Roman Empires, the history of Christianity and Western culture took divergent routes, with a final Great Schism separating Roman and Eastern Christianity in 1054AD.

Saint Ambrose and Emperor Theodosius, Anthony van Dyck.

Pope Gregory the Great (c 540–604) who established medieval themes in the Church, in a painting by Carlo Saraceni, c. 1610, Rome.

The remarkable transformation of Christianity from peripheral sect, to major force within the Empire is illustrated by the influence held by St Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan. A Doctor of the Church and one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures of the 4th century, Ambrose became a player in Imperial politics, courted for his influence by competing contenders for the Imperial throne. When the Emperor Theodosius I ordered the punitive massacre of thousands of the citizens of Thessaloniki, Ambrose admonished him publicly, refused him the Eucharist and called on him to perform a public penance, a call to which the Christian Emperor submitted.[49][50] While paganism in the Roman Empire was not yet finished, the episode prefigured the role of the Church in the political life of Europe in coming centuries.

Theodosius reigned (albeit for a brief interim) as the last Emperor of a united Eastern and Western Roman Empire. In 391 Theodosius sought to block the restoration of the pagan Altar of Victory to the Roman Senate and then fought against Eugenius, who courted pagan support for his own bid for the imperial throne. Thus, the Catholic Encyclopedia lauds Theodosius as:[51]

[O]ne of the sovereigns by universal consent called Great. He stamped out the last vestiges of paganism, put an end to the Arian heresy in the empire, pacified the Goths, left a famous example of penitence for a crime, and reigned as a just and mighty Catholic emperor.

Fourth Century

During the fourth century, Christian writing and theology blossomed into a “Golden Age” of literary and scholarly activity unmatched since the days of Virgil and Horace. Many of these works remain influential in politics, law, ethics and other fields. A new genre of literature was also born in the fourth century: church history.[52][53]

The Fall of Rome

After the Fall of Rome culture in the west returned to a subsistence agrarian form of life. What little security there was in this world was provided by the Christian church.[54][1][55] The papacy served as a source of authority and continuity at this critical time. In the absence of a magister militum living in Rome, even the control of military matters fell to the pope. Gregory the Great (c 540–604) administered the church with strict reform. A trained Roman lawyer and administrator, and a monk, he represents the shift from the classical to the medieval outlook and was a father of many of the structures of the later Roman Catholic Church. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, he looked upon Church and State as co-operating to form a united whole, which acted in two distinct spheres, ecclesiastical and secular, but by the time of his death, the papacy was the great power in Italy:[56]

[ Pope Gregory the Great ] made himself in Italy a power stronger than emperor or exarch, and established a political influence which dominated the peninsula for centuries. From this time forth the varied populations of Italy looked to the pope for guidance, and Rome as the papal capital continued to be the centre of the Christian world.

The Dark Ages

The period between 500 and 700, often referred to as the "Dark Ages," could also be designated the "Age of the Monk". Christian aesthetes, like St.Benedict (480–543) vowed a life of chastity, obedience and poverty, and after rigorous intellectual training and self-denial, lived by the “Rule of Benedict.” This “Rule” became the foundation of the majority of the thousands of monasteries that spread across what is modern day Europe; "...certainly there will be no demur in recognizing that St.Benedict's Rule has been one of the great facts in the history of western Europe, and that its influence and effects are with us to this day."[54]:intro.

Monasteries were models of productivity and economic resourcefulness teaching their local communities animal husbandry, cheese making, wine making and various other skills.[57] They were havens for the poor, hospitals, hospices for the dying, and schools. Medical practice was highly important in medieval monasteries, and they are best known for their contributions to medical tradition, but they also made some advances in other sciences such as astronomy.[58] For centuries, nearly all secular leaders were trained by monks simply because, excepting private tutors, it was the only education available.[59]

The formation of these organized bodies of believers distinct from political and familial authority, especially for women, gradually carved out a series of social spaces with some amount of independence thereby revolutionizing social history.[60]

Medieval period

Early Middle Ages

Charlemagne ("Charles the Great" in English) became king of the Franks in 768. He conquered the Low Countries, Saxony, and northern and central Italy, and in 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor. Sometimes called the "Father of Europe," Charlemagne instituted political and judicial reform and led what is sometimes referred to as the Early or Christian Renaissance.[61]

Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII in Canossa 1077, as depicted by Carlo Emanuelle

The historian Geoffrey Blainey, likened the Catholic Church in its activities during the Middle Ages to an early version of a welfare state: "It conducted hospitals for the old and orphanages for the young; hospices for the sick of all ages; places for the lepers; and hostels or inns where pilgrims could buy a cheap bed and meal". It supplied food to the population during famine and distributed food to the poor. This welfare system the church funded through collecting taxes on a large scale and by owning large farmlands and estates.[62]

High Middle Ages

By the late 11th century, beginning with the efforts of Pope Gregory VII, the Church successfully established itself as "an autonomous legal and political ... [entity] within Western Christendom".[63] For the next several hundred years, the Church held great influence over Western society;[63] church laws were the single "universal law ... common to jurisdictions and peoples throughout Europe", giving the Church "preeminent authority".[64] With its own court system, the Church retained jurisdiction over many aspects of ordinary life, including education, inheritance, oral promises, oaths, moral crimes, and marriage.[65] As one of the more powerful institutions of the Middle Ages, Church attitudes were reflected in many secular laws of the time.[66]

The Catholic Church was very powerful, essentially internationalist and democratic in it structures and run by monastic organisations generally following Benedictine rule. Men of a scholarly bent usually took Holy Orders and frequently joined religious institutes. Those with intellectual, administrative or diplomatic skill could advance beyond the usual restraints of society – leading churchmen from faraway lands were accepted in local bishoprics, linking European thought across wide distances. Complexes like the Abbey of Cluny became vibrant centres with dependencies spread throughout Europe. Ordinary people also treked vast distances on pilgrimages to express their piety and pray at the site of holy relics.[67]

Inquisition

The Inquisitions were religious courts originally created to protect faith and society by identifying and condemning heretics.[55]:250[68]The Medieval Inquisition existed from 1184 to the 1230s and was created in response to dissidents accused of heresy, while the Papal Inquisition (1230's-1302) was created to restore order disrupted by mob violence against heretics. "The [Medieval] Inquisition was not an organization arbitrarily devised and imposed upon the judicial system of Christendom by the ambition or fanaticism of the church. It was rather a natural—one may almost say an inevitable—evolution of the forces at work in the thirteenth century... As the twelfth century drew to a close the church was facing a crisis..."[69] This crisis centered around dissidents, the ever-increasing power of the secular state, the declining power of the papacy, and the gradual disintegration of Christendom.[70] After the Medieval Inquisitions were suspended, the Catholic Inquisitions known as the Roman, the Spanish and the Portuguese Inquisitions, were begun with the Spanish lasting four centuries into the 1800s.[70]:154

Late Middle Ages

Women

In the 13th-century Roman Pontifical, the prayer for ordaining women as deacons was removed, and ordination was re-defined and applied only to male Priests.

Woman-as-witch became a stereotype in the 1400s until it was codified in 1487 by Pope Innocent VIII who declared "most witches are female." "The European witch stereotype embodies two apparent paradoxes: first, it was not produced by the "barbaric Dark Ages," but during the progressive Renaissance and the early modern period; secondly, Western Christianity did not recognize the reality of witches for centuries, or criminalize them until around 1400."[71] Sociologist Don Swenson says the explanation for this may lay in the nature of Medieval society as heirocratic which led to violence and the use of coercion to force conformity. "There has been much debate ...as to how many women were executed...[and estimates vary wildly, but numbers] small and large do little to portray the horror and dishonor inflicted upon these women. This treatment provides [dramatic] contrast to the respect given to women during the early era of Christianity and in early Europe..."[72]

Women were in many respects excluded from political and mercantile life; however, some leading churchwomen were exceptions. Medieval abbesses and female superiors of monastic houses were powerful figures whose influence could rival that of male bishops and abbots: "They treated with kings, bishops, and the greatest lords on terms of perfect equality;... they were present at all great religious and national solemnities, at the dedication of churches, and even, like the queens, took part in the deliberation of the national assemblies...".[73] The increasing popularity of devotion to the Virgin Mary (the mother of Jesus) secured maternal virtue as a central cultural theme of Catholic Europe. Kenneth Clarke wrote that the 'Cult of the Virgin' in the early 12th century "had taught a race of tough and ruthless barbarians the virtues of tenderness and compassion".[74]

The Popes

In 1054, after centuries of strained relations, the Great Schism occurred over differences in doctrine, splitting the Christian world between the Catholic Church, centered in Rome and dominant in the West, and the Orthodox Church, centered in Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire.

Relations between the major powers in Western society: the nobility, monarchy and clergy, sometimes produced conflict. Pope's were powerful enough to challenge the authority of kings. The Investiture Controversy was perhaps the most significant conflict between Church and state in medieval Europe. A series of Popes challenged the authority of monarchies over control of appointments, or investitures, of church officials. The Court of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, based in Sicily, saw tension and rivalry with the Papacy over control of Northern Italy.[75] The Papacy had its court at Avignon from 1305–78[76] This arose from the conflict between the Italian Papacy and the French crown.

"The Popes in the fourteenth to the mid-fifteenth century turned their interest to the arts and humanities rather than to pressing moral and spiritual issues. Moreover, they were vitally concerned with the trappings of political power. They plunged into Italian politics...ruling as secular princes in their papal lands. Their worldly interests and blatant political maneuverings only intensified the mounting disapproval of the papacy and provided the church's critics with more examples of the institution's corruption and decline."[55]:248 This period produced ever more extravagant art and architecture, but also the virtuous simplicity of such as St Francis of Assisi (expressed in the Canticle of the Sun) and the epic poetry of Dante's Divine Comedy. As the Church grew more powerful and wealthy, many sought reform. The Dominican and Franciscan Orders were founded, which emphasized poverty and spirituality.

Crusade

In 1095, Pope Urban II called for a Crusade to re-take the Holy Land from Muslim rule.

"After Mohammad's death in 632, a series of caliphs (successors) waged energetic jihad against neighboring people's. Palestine, Syria, Persia, and Egypt—once the most heavily Christian areas in the world—quickly succumbed. By the eighth century, Muslim armies had conquered all of Christian North Africa and Spain and were moving into France. In 732, at the Battle of Tours, Charles Martel defeated Muslim invaders and sent them back into Spain. By the eleventh century, the Seljuk Turks had conquered Asia Minor (modern Turkey), which had been Christian since the time of St. Paul. The holdings of the old Roman Empire, known to modern historians as the Byzantine Empire, were reduced to little more than Greece. In desperation, the emperor in Constantinople sent word to the Christians of western Europe asking them to aid their brothers and sisters in the East."[77][78] This was the first crusade, but the "Colossus of the Medieval world was Islam, not Christendom" and despite initial success, the conflicts, which lasted four centuries, ultimately ended in a failure to retake the "Holy Land" and only barely prevented the taking of the European continent.[78][55]:192

Historian Jonathan Riley-Smith says scholars are turning away from the idea subsequent crusades were materially motivated. A more complex picture of nobles and knights making sacrifices has emerged creating an increased interest in the religious and social ideas of the laity. Crusading can no longer be defined solely as warfare against Muslims; the crusades were religious wars and the crusaders moved by ideas; and the issue of colonialism is no longer one considered worthy of serious discussion.[79]

Human Rights

"The philosophical foundation of the liberal concept of human rights can be found in natural law theories,"[80][81] and much thinking on natural law is traced to the thought of the Dominican friar, Thomas Aquinas.[82] According to Aquinas, every law is ultimately derived from what he calls the 'eternal law': God's ordering of all created things. For Aquinas, a human action is good or bad depending on whether it conforms to reason, and it is this participation in the 'eternal law' by the 'rational creature' that is called “natural law.” Aquinas said natural law is a fundamental principle that is woven into the fabric of human nature. Secularists such as Hugo Grotius later expanded the idea of human rights and built on it. Aquinas continues to influence the works of leading political and legal philosophers.[82]

"...one cannot and need not deny that Human Rights are of Western Origin. It cannot be denied, because they are morally based on the Judeo-Christian tradition and Graeco-Roman philosophy; they were codified in the West over many centuries, they have secured an established position in the national declarations of western democracies, and they have been enshrined in the constitutions of those democracies."[83]

Howard Tumber says, "human rights is not a universal doctrine, but is the descendent of one particular religion (Christianity)." This does not suggest Christianity has been superior in its practice or has not had "its share of human rights abuses".[84]

David Gushee says Christianity has a "tragically mixed legacy" when it comes to the application of its own ethics. He examines three cases of "Christendom divided against itself": the crusades and Frances' attempt at peacemaking with Muslims; Spanish conquerors and the killing of indigenous peoples and the protests against it; and the on-again off-again persecution and protection of Jews.[85]

Charles Malik, a Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher and theologian was responsible for the drafting and adoption of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Reformation until Modern era

Calvin preached at St. Pierre Cathedral, the main church in Geneva.

In the Middle Ages, the Church and the worldly authorities were closely related. Martin Luther separated the religious and the worldly realms in principle (doctrine of the two kingdoms).[86] The believers were obliged to use reason to govern the worldly sphere in an orderly and peaceful way. Luther's doctrine of the priesthood of all believers upgraded the role of laymen in the church considerably. The members of a congregation had the right to elect a minister and, if necessary, to vote for his dismissal (Treatise On the right and authority of a Christian assembly or congregation to judge all doctrines and to call, install and dismiss teachers, as testified in Scripture; 1523).[87] Calvin strengthened this basically democratic approach by including elected laymen (church elders, presbyters) in his representative church government.[88] The Huguenots added regional synods and a national synod, whose members were elected by the congregations, to Calvin's system of church self-government. This system was taken over by the other Reformed churches.[89]

Politically, John Calvin favoured a mixture of aristocracy and democracy. He appreciated the advantages of democracy: "It is an invaluable gift, if God allows a people to freely elect its own authorities and overlords."[90] Calvin also thought that earthly rulers lose their divine right and must be put down when they rise up against God. To further protect the rights of ordinary people, Calvin suggested separating political powers in a system of checks and balances (separation of powers). Thus he and his followers resisted political absolutism and paved the way for the rise of modern democracy.[91] Besides England, the Netherlands were, under Calvinist leadership, the freest country in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It granted asylum to philosophers like René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza and Pierre Bayle. Hugo Grotius was able to teach his natural-law theory and a relatively liberal interpretation of the Bible.[92]

Consistent with Calvin's political ideas, Protestants created both the English and the American democracies. In 17th-century England, the most important persons and events in this process were the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell, John Milton, John Locke, the Glorious Revolution, the English Bill of Rights, and the Act of Settlement.[93] Later, the British took their democratic ideals also to their colonies, e.g. Australia, New Zealand, and India. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the British variety of modern-time democracy, constitutional monarchy, was taken over by Protestant-formed Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and the Netherlands as well as the Catholic countries Belgium and Spain. In North America, Plymouth Colony (Pilgrim Fathers; 1620) and Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628) practised democratic self-rule and separation of powers.[94][95][96][97] These Congregationalists were convinced that the democratic form of government was the will of God.[98] The Mayflower Compact was a social contract.[99][100]

Sexual morals

Historian Kyle Harper says

"...the triumph of Christianity not only drove profound cultural change, it created a new relationship between sexual morality and society... The legacy of Christianity lies in the dissolution of an ancient system where social and political status, power, and the transmission of social inequality to the next generation scripted the terms of sexual morality."

[101]

Both the ancient Greeks and the Romans cared and wrote about sexual morality within categories of good and bad, pure and defiled, and ideal and transgression.[102] But the sexual ethical structures of Roman society were built on status, and sexual modesty meant something different for men than it did for women, and for the well-born, than it did for the poor, and for the free citizen, than it did for the slave—for whom the concepts of honor, shame and sexual modesty could be said to have no meaning at all.[101]:7 Slaves were not thought to have an interior ethical life because they could go no lower socially and were commonly used sexually; the free and well born were thought to embody social honor and were therefore able to exhibit the fine sense of shame suited to their station. Roman literature indicates the Romans were aware of these dualities.[102]:12,20

Shame was a profoundly social concept that was, in ancient Rome, always mediated by gender and status. "It was not enough that a wife merely regulate her sexual behavior in the accepted ways; it was required that her virtue in this area be conspicuous."[102]:38 Men, on the other hand, were allowed live-in mistresses called pallake.[103] This permitted Roman society to find both a husband's control of a wife's sexual behavior a matter of intense importance and at the same time see his own sex with young boys as of little concern.[102]:12,20 Christianity sought to establish equal sexual standards for men and women and to protect all the young whether slave or free. This was a transformation in the deep logic of sexual morality.[101]:6,7

Early Church Fathers advocated against adultery, polygamy, homosexuality, pederasty, bestiality, prostitution, and incest while advocating for the sanctity of the marriage bed.[104] The central Christian prohibition against such porneia, which is a single name for that array of sexual behaviors, "collided with deeply entrenched patterns of Roman permissiveness where the legitimacy of sexual contact was determined primarily by status. St.Paul, whose views became dominant in early Christianity, made the body into a consecrated space, a point of mediation between the individual and the divine. Same-sex attraction spelled the estrangement of men and women at the very deepest level of their inmost desires. Paul's over-riding sense that gender—rather than status or power or wealth or position—was the prime determinant in the propriety of the sex act was momentous. By boiling the sex act down to the most basic constituents of male and female, Paul was able to describe the sexual culture surrounding him in transformative terms."[101]:12,92

Christian sexual ideology is inextricable from its concept of freewill. "In its original form, Christian freewill was a cosmological claim—an argument about the relationship between God's justice and the individual... as Christianity became intermeshed with society, the discussion shifted in revealing ways to the actual psychology of volition and the material constraints on sexual action... The church's acute concern with volition places Christian philosophy in the liveliest currents of imperial Greco-Roman philosophy [where] orthodox Christians offered a radically distinctive version of it."[101]:14 The Greeks and Romans said our deepest moralities depend on our social position which is given to us by fate. Christianity "preached a liberating message of freedom. It was a revolution in the rules of behavior, but also in the very image of the human being as a sexual being, free, frail and awesomely responsible for one's own self to God alone. It was a revolution in the nature of society's claims on the moral agent... There are risks in over-estimating the change in old patterns Christianity was able to begin bringing about; but there are risks, too, in underestimating Christianization as a watershed."[101]:14–18

Marriage and family life

"Therefore what God has joined together, let not man separate." (Gospel of Matthew 19:6) Matrimony, The Seven Sacraments, Rogier van der Weyden, ca. 1445.

The teachings of the Church have also been used to "establish[...] the status of women under the law".[105] There has been some debate as to whether the Church has improved the status of women or hindered their progress.

Orthodox wedding, Cathedral of Ss. Cyrill and Methodius, Prague, Czech Republic.

From the beginning of the thirteenth century, the Church formally recognized marriage between a freely consenting, baptized man and woman as a sacrament—an outward sign communicating a special gift of God's love. The Council of Florence in 1438 gave this definition, following earlier Church statements in 1208, and declared that sexual union was a special participation in the union of Christ in the Church.[106] However, the Puritans, while highly valuing the institution, viewed marriage as a "civil", rather than a "religious" matter, being "under the jurisdiction of the civil courts".[107] This is because they found no biblical precedent for clergy performing marriage ceremonies. Further, marriage was said to be for the "relief of concupiscence"[107] as well as any spiritual purpose.

During the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther and John Calvin denied the sacramentality of marriage. This unanimity was broken at the 1930 Lambeth Conference, the quadrennial meeting of the worldwide Anglican Communion—creating divisions in that denomination.

Sex before marriage was not a taboo in the Anglican Church until the "Hardwicke Marriage Act of 1753, which for the first time stipulated that everyone in England and Wales had to be married in their parish church"[108] Prior to that time, "marriage began at the time of betrothal, when couples would live and sleep together... The process begun at the time of the Hardwicke Act continued throughout the 1800s, with stigma beginning to attach to illegitimacy."[108]

Scriptures in the New Testament dealing with sexuality are extensive. Subjects include: the Apostolic Decree (Acts 15), sexual immorality, divine love (1 Corinthians 13), mutual self-giving (1 Corinthians 7), bodily membership between Christ and between husband and wife (1 Corinthians 6:15–20) and honor versus dishonor of adultery (Hebrews 13:4).

Roman Empire

Social structures before and at the dawn of Christianity in the Roman Empire held that women were inferior to men intellectually and physically and were "naturally dependent".[109]Athenian women were legally classified as children regardless of age and were the "legal property of some man at all stages in her life."[110] Women in the Roman Empire had limited legal rights and could not enter professions. Female infanticide and abortion were practiced by all classes.[110] In family life, men could have "lovers, prostitutes and concubines" but wives who engaged in extramarital affairs were considered guilty of adultery. It was not rare for pagan women to be married before the age of puberty and then forced to consummate the marriage with her often much older husband. Husbands could divorce their wives at any time simply by telling the wife to leave; wives did not have a similar ability to divorce their husbands.[109]

Early Church Fathers advocated against polygamy, abortion, infanticide, child abuse, homosexuality, transvestism, and incest.[104] Although some Christian ideals were adopted by the Roman Empire, there is little evidence to link most of these laws to Church influence.[111] After the Roman Empire adopted Christianity as the official religion, however, the link between Christian teachings and Roman family laws became more clear.[112]

For example, Church teaching heavily influenced the legal concept of marriage.[105] During the Gregorian Reform, the Church developed and codified a view of marriage as a sacrament.[63] In a departure from societal norms, Church law required the consent of both parties before a marriage could be performed[104] and established a minimum age for marriage.[113] The elevation of marriage to a sacrament also made the union a binding contract, with dissolutions overseen by Church authorities.[114] Although the Church abandoned tradition to allow women the same rights as men to dissolve a marriage,[115] in practice, when an accusation of infidelity was made, men were granted dissolutions more frequently than women.[116]

Medieval period

According to historian Shulamith Shahar, "[s]ome historians hold that the Church played a considerable part in fostering the inferior status of women in medieval society in general" by providing a "moral justification" for male superiority and by accepting practices such as wife-beating.[117] Despite these laws, some women, particularly abbesses, gained powers that were never available to women in previous Roman or Germanic societies.[118]

Although these teachings emboldened secular authorities to give women fewer rights than men, they also helped form the concept of chivalry.[119] Chivalry was influenced by a new Church attitude towards Mary, the mother of Jesus.[120] This "ambivalence about women's very nature" was shared by most major religions in the Western world.[121]

Slavery

The Church initially accepted slavery as part of the Greco-Roman social fabric of society, campaigning primarily for humane treatment of slaves but also admonishing slaves to behave appropriately towards their masters.[122] Historian Glenn Sunshine says, "Christians were the first people in history to oppose slavery systematically. Early Christians purchased slaves in the markets simply to set them free. Later, in the seventh century, the Franks..., under the influence of its Christian queen, Bathilde, became the first kingdom in history to begin the process of outlawing slavery. ...In the 1200's, Thomas Aquinas declared slavery a sin. When the African slave trade began in the 1400's, it was condemned numerous times by the papacy."[123]

During the early medieval period, Christians tolerated enslavement of non-Christians. By the end of the Medieval period, enslavement of Christians had been mitigated somewhat with the spread of serfdom within Europe, though outright slavery existed in European colonies in other parts of the world. Several popes issued papal bulls condemning mistreatment of enslaved Native Americans; these were largely ignored. In his 1839 bull In supremo apostolatus, Pope Gregory XVI condemned all forms of slavery; nevertheless some American bishops continued to support slavery for several decades.[124] In this historic Bull, Pope Gregory outlined his summation of the impact of the Church on the ancient institution of slavery, beginning by acknowledging that early Apostles had tolerated slavery but had called on masters to "act well towards their slaves... knowing that the common Master both of themselves and of the slaves is in Heaven, and that with Him there is no distinction of persons". Gregory continued to discuss the involvement of Christians for and against slavery through the ages:[125]

| “ | In the process of time, the fog of pagan superstition being more completely dissipated and the manners of barbarous people having been softened, thanks to Faith operating by Charity, it at last comes about that, since several centuries, there are no more slaves in the greater number of Christian nations. But – We say with profound sorrow – there were to be found afterwards among the Faithful men who, shamefully blinded by the desire of sordid gain, in lonely and distant countries, did not hesitate to reduce to slavery Indians, negroes and other wretched peoples, or else, by instituting or developing the trade in those who had been made slaves by others, to favour their unworthy practice. Certainly many Roman Pontiffs of glorious memory, Our Predecessors, did not fail, according to the duties of their charge, to blame severely this way of acting as dangerous for the spiritual welfare of those engaged in the traffic and a shame to the Christian name; they foresaw that as a result of this, the infidel peoples would be more and more strengthened in their hatred of the true Religion. | ” |

Latin America

Saint Peter Claver worked for the alleviation of the suffering of African slaves brought to South America.

It was women, primarily Amerindian Christian converts who became the primary supporters of the Latin American Church.[126] While the Spanish military was known for its ill-treatment of Amerindian men and women, Catholic missionaries are credited with championing all efforts to initiate protective laws for the Indians and fought against their enslavement. This began within 20 years of the discovery of the New World by Europeans in 1492 – in December 1511, Antonio de Montesinos, a Dominican friar, openly rebuked the Spanish rulers of Hispaniola for their "cruelty and tyranny" in dealing with the American natives.[127]King Ferdinand enacted the Laws of Burgos and Valladolid in response. The issue resulted in a crisis of conscience in 16th-century Spain.[128] Further abuses against the Amerindians committed by Spanish authorities were denounced by Catholic missionaries such as Bartolomé de Las Casas and Francisco de Vitoria which led to debate on the nature of human rights[129] and the birth of modern international law.[130] Enforcement of these laws was lax, and some historians blame the Church for not doing enough to liberate the Indians; others point to the Church as the only voice raised on behalf of indigenous peoples.[131]

Slavery and human sacrifice were both part of Latin American culture before the Europeans arrived. Indian slavery was first abolished by Pope Paul III in the 1537 bull Sublimis Deus which confirmed that "their souls were as immortal as those of Europeans" and they should neither be robbed nor turned into slaves.[132] While these edicts may have had some beneficial effects, these were limited in scope. European colonies were mainly run by military and royally-appointed administrators, who seldom stopped to consider church teachings when forming policy or enforcing their rule. Even after independence, institutionalized prejudice and injustice toward indigenous people continued well into the twentieth century. This has led to the formation of a number of movements to reassert indigenous peoples' civil rights and culture in modern nation-states.

A catastrophe was wrought upon the Amerindians by contact with Europeans. Old World diseases like smallpox, measles, malaria and many others spread through Indian populations. "In most of the New World 90 percent or more of the native population was destroyed by wave after wave of previously unknown afflictions. Explorers and colonists did not enter an empty land but rather an emptied one".[133]

Africa

Slavery and the slave trade were part of African societies and states which supplied the Arab world with slaves before the arrival of the Europeans.[134] Several decades prior to discovery of the New World, in response to serious military threat to Europe posed by Muslims of the Ottoman Empire, Pope Nicholas V had granted Portugal the right to subdue Muslims, pagans and other unbelievers in the papal bull Dum Diversas (1452).[135] Six years after African slavery was first outlawed by the first major entity to do so, (Great Britain in 1833), Pope Gregory XVI followed in a challenge to Spanish and Portuguese policy, by condemning slavery and the slave trade in the 1839 papal bull In supremo apostolatus, and approved the ordination of native clergy in the face of government racism.[136] The United States would eventually outlaw African slavery in 1865.

By the close of the 19th century, European powers had managed to gain control of most of the African interior.[137] The new rulers introduced cash-based economies which created an enormous demand for literacy and a western education—a demand which for most Africans could only be satisfied by Christian missionaries.[137] Catholic missionaries followed colonial governments into Africa, and built schools, hospitals, monasteries and churches.[137]

Letters and learning

Map of mediaeval universities established by Catholic students, faculty, monarchs, or priests

The influence of the Church on Western letters and learning has been formidable. The ancient texts of the Bible have deeply influenced Western art, literature and culture. For centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, small monastic communities were practically the only outposts of literacy in Western Europe. In time, the Cathedral schools developed into Europe's earliest universities and the church has established thousands of primary, secondary and tertiary institutions throughout the world in the centuries since. The Church and clergymen have also sought at different times to censor texts and scholars. Thus different schools of opinion exist as to the role and influence of the Church in relation to western letters and learning.

One view, first propounded by Enlightenment philosophers, asserts that the Church's doctrines are entirely superstitious and have hindered the progress of civilization. Communist states have made similar arguments in their education in order to inculcate a negative view of Catholicism (and religion in general) in their citizens. The most famous incidents cited by such critics are the Church's condemnations of the teachings of Copernicus, Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler.

Set of pictures for a number of notable Scientists self-identified as Christians: Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, Francis Bacon and Johannes Kepler.

In opposition to this view, some historians of science, including non-Catholics such as J.L. Heilbron,[138]A.C. Crombie, David Lindberg,[139]Edward Grant, historian of science Thomas Goldstein,[140] and Ted Davis, have argued that the Church had a significant, positive influence on the development of Western civilization. They hold that, not only did monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but that the Church promoted learning and science through its sponsorship of many universities which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries. Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, and Johannes Kepler all considered themselves Christian. St.Thomas Aquinas, the Church's "model theologian," argued that reason is in harmony with faith, and that reason can contribute to a deeper understanding of revelation, and so encouraged intellectual development.[141] The Church's priest-scientists, many of whom were Jesuits, have been among the leading lights in astronomy, genetics, geomagnetism, meteorology, seismology, and solar physics, becoming some of the "fathers" of these sciences. Examples include important churchmen such as the Augustinian abbot Gregor Mendel (pioneer in the study of genetics), the monk William of Ockham who developed Ockham's Razor, Roger Bacon (a Franciscan friar who was one of the early advocates of the scientific method), and Belgian priest Georges Lemaître (the first to propose the Big Bang theory). Other notable priest scientists have included Albertus Magnus, Robert Grosseteste, Nicholas Steno, Francesco Grimaldi, Giambattista Riccioli, Roger Boscovich, and Athanasius Kircher. Even more numerous are Catholic laity involved in science:Henri Becquerel who discovered radioactivity; Galvani, Volta, Ampere, Marconi, pioneers in electricity and telecommunications; Lavoisier, "father of modern chemistry"; Vesalius, founder of modern human anatomy; and Cauchy, one of the mathematicians who laid the rigorous foundations of calculus.

Many well-known historical figures who influenced Western science considered themselves Christian such as Copernicus,[142]Galileo,[143]Kepler,[144]Newton[145] and Boyle.[146]

According to 100 Years of Nobel Prize (2005), a review of Nobel prizes awarded between 1901 and 2000, 65.4% of Nobel Prize Laureates, have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference (423 prizes).[147] Overall, Christians have won a total of 78.3% of all the Nobel Prizes in Peace,[148] 72.5% in Chemistry, 65.3% in Physics,[148] 62% in Medicine,[148] 54% in Economics[148] and 49.5% of all Literature awards.[148]

Antiquity

David dictating the Psalms, book cover. Ivory, end of the 10th century–11th century.

Christianity began as a Jewish sect in the 1st century AD, and from the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth and his early followers. Jesus learned the texts of the Hebrew Bible and became an influential wandering preacher. Accounts of his life and teachings appear in the New Testament of the Bible, one of the bedrock texts of Western Civilisation.[33] His orations, including the Sermon on the Mount, The Good Samaritan and his declaration against hypocrisy "Let he who is without sin cast the first stone" have been deeply influential in Western literature. Many translations of the Bible exist, including the King James Bible, which is one of the most admired texts in English literature. The poetic Psalms and other passages of the Hebrew Bible have also been deeply influential in Western Literature and thought. Accounts of the actions of Jesus' early followers are contained within the Acts of the Apostles and Epistles written between the early Christian communities – in particular the Pauline epistles which are among the earliest extant Christian documents and foundational texts of Christian theology.

After the death of Jesus, the new sect grew to be the dominant religion of the Roman Empire and the long tradition of Christian scholarship began. When the Western Roman Empire was starting to disintegrate, St Augustine was Bishop of Hippo Regius.[149] He was a Latin-speaking philosopher and theologian who lived in the Roman Africa Province. His writings were very influential in the development of Western Christianity and he developed the concept of the Church as a spiritual City of God (in a book of the same name), distinct from the material Earthly City.[150] His book Confessions, which outlines his sinful youth and conversion to Christianity, is widely considered to be the first autobiography of ever written in the canon of Western Literature. Augustine profoundly influenced the coming medieval worldview.[151]

Byzantine Empire

Interior panorama of the Hagia Sophia, the patriarchal basilica in Constantinople designed 537 CE by Isidore of Miletus, the first compiler of Archimedes' various works. The influence of Archimedes' principles of solid geometry is evident.

The writings of Classical antiquity never ceased to be cultivated in Byzantium. Therefore, Byzantine science was in every period closely connected with ancient philosophy, and metaphysics.[152] In the field of engineering Isidore of Miletus, the Greek mathematician and architect of the Hagia Sophia, produced the first compilation of Archimedes works c. 530, and it is through this tradition, kept alive by the school of mathematics and engineering founded c. 850 during the "Byzantine Renaissance" by Leo the Geometer that such works are known today (see Archimedes Palimpsest).[153] Indeed, geometry and its applications (architecture and engineering instruments of war) remained a specialty of the Byzantines.

The frontispiece of the Vienna Dioscurides, which shows a set of seven famous physicians

Though scholarship lagged during the dark years following the Arab conquests, during the so-called Byzantine Renaissance at the end of the first millennium Byzantine scholars re-asserted themselves becoming experts in the scientific developments of the Arabs and Persians, particularly in astronomy and mathematics.[154] The Byzantines are also credited with several technological advancements, particularly in architecture (e.g. the pendentive dome) and warfare technology (e.g. Greek fire).

Although at various times the Byzantines made magnificent achievements in the application of the sciences (notably in the construction of the Hagia Sophia), and although they preserved much of the ancient knowledge of science and geometry, after the 6th century Byzantine scholars made few novel contributions to science in terms of developing new theories or extending the ideas of classical authors.[155]

In the final century of the Empire, Byzantine grammarians were those principally responsible for carrying, in person and in writing, ancient Greek grammatical and literary studies to early Renaissance Italy.[156] During this period, astronomy and other mathematical sciences were taught in Trebizond; medicine attracted the interest of almost all scholars.[157]

In the field of law, Justinian I's reforms had a clear effect on the evolution of jurisprudence, and Leo III's Ecloga influenced the formation of legal institutions in the Slavic world.[158]

In the 10th century, Leo VI the Wise achieved the complete codification of the whole of Byzantine law in Greek, which became the foundation of all subsequent Byzantine law, generating interest to the present day.

Preservation of Classical learning

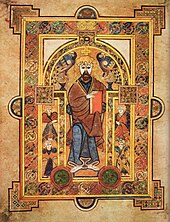

The Book of Kells. Celtic Church scholars did much to preserve the texts of ancient Europe through the Dark Ages.

During the period of European history often called the Dark Ages which followed the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, Church scholars and missionaries played a vital role in preserving knowledge of Classical Learning. While the Roman Empire and Christian religion survived in an increasingly Hellenised form in the Byzantine Empire centred at Constantinople in the East, Western civilisation suffered a collapse of literacy and organisation following the fall of Rome in 476AD. Monks sought refuge at the far fringes of the known world: like Cornwall, Ireland, or the Hebrides. Disciplined Christian scholarship carried on in isolated outposts like Skellig Michael in Ireland, where literate monks became some of the last preservers in Western Europe of the poetic and philosophical works of Western antiquity.[159] By around 800AD they were producing illuminated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells, by which old learning was re-communicated to Western Europe. The Hiberno-Scottish mission led by Irish and Scottish monks like St Columba spread Christianity back into Western Europe during the Middle Ages, establishing monasteries through Anglo-Saxon England and the Frankish Empire during the Middle Ages.

Thomas Cahill, in his 1995 book How the Irish Saved Civilization, credited Irish Monks with having "saved" Western Civilization:[160]

[A]s the Roman Empire fell, as all through Europe matted, unwashed barbarians descended on the Roman cities, looting artifacts and burning books, the Irish, who were just learning to read and write, took up th great labor of copying all western literature – everything they could lay their hands on. These scribes then served as conduits through which the Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian cultures were transmitted to the tribes of Europe, newly settled amid the rubble and ruined vineyards of the civilization they had overwhelmed. Without this Service of the Scribes, everything that happened subsequently would be unthinkable. Without the Mission of the Irish Monks, who single-handedly re-founded European civilization throughout the continent in the bays and valleys of their exile, the world that came after them would have been an entirely different one-a world without books. And our own world would never have come to be.

According to art historian Kenneth Clark, for some five centuries after the fall of Rome, virtually all men of intellect joined the Church and practically nobody in western Europe outside of monastic settlements had the ability to read or write. While church scholars at different times also destroyed classical texts they felt were contrary to the Christian message, it was they, virtually alone in Western Europe, who preserved texts from the old society.[159]

As Western Europe became more orderly again, the Church remained a driving force in education, setting up Cathedral schools beginning in the Early Middle Ages as centers of education, which became medieval universities, the springboard of many of Western Europe's later achievements.

Index Librorum Prohibitorum

Title page of Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Venice 1564).

The Index Librorum Prohibitorum ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications prohibited by the Catholic Church. The promulgation of the Index marked the "turning-point in the freedom of enquiry" in the Catholic world.[161] The first Index was published in 1559 by the Sacred Congregation of the Roman Inquisition. The last edition of the Index appeared in 1948 and publication of the list ceased 1966.[162]

The avowed aim of the list was to protect the faith and morals of the faithful by preventing the reading of immoral books or works containing theological errors. Books thought to contain such errors included some scientific works by leading astronomers such as Johannes Kepler's Epitome astronomiae Copernicianae, which was on the Index from 1621 to 1835. The various editions of the Index also contained the rules of the Church relating to the reading, selling and pre-emptive censorship of books.

Canon law still recommends that works concerning sacred Scripture, theology, canon law, church history, and any writings which specially concern religion or good morals, be submitted to the judgement of the local Ordinary.[163]

Some of the scientific works that were on early editions of the Index (e.g. on heliocentrism) have long been routinely taught at Catholic universities worldwide. Giordano Bruno, whose works were on the Index, now has a monument in Rome, erected over the Church's objections at the place where he was burned alive at the stake for heresy.

Protestant role in science

According to the Merton Thesis there was a positive correlation between the rise of puritanism and protestant pietism on the one hand and early experimental science on the other.[164] The Merton Thesis has two separate parts: Firstly, it presents a theory that science changes due to an accumulation of observations and improvement in experimental techniques and methodology; secondly, it puts forward the argument that the popularity of science in 17th-century England and the religious demography of the Royal Society (English scientists of that time were predominantly Puritans or other Protestants) can be explained by a correlation between Protestantism and the scientific values.[165] In his theory, Robert K. Merton focused on English Puritanism and German Pietism as having been responsible for the development of the scientific revolution of the 17th and 18th centuries. Merton explained that the connection between religious affiliation and interest in science was the result of a significant synergy between the ascetic Protestant values and those of modern science.[166] Protestant values encouraged scientific research by allowing science to study God's influence on the world and thus providing a religious justification for scientific research.[164]

Astronomy

Vatican Observatory Telescope in Castel Gandolfo.

Historically, the Catholic Church has been a major a sponsor of astronomy, not least due to the astronomical basis of the calendar by which holy days and Easter are determined. Nevertheless, the most famous case of a scientist being tried for heresy arose in this field of science: the trial of Galileo.

The Church's interest in astronomy began with purely practical concerns, when in the 16th century Pope Gregory XIII required astronomers to correct for the fact that the Julian calendar had fallen out of sync with the sky. Since the Spring equinox was tied to the celebration of Easter, the Church considered that this steady movement in the date of the equinox was undesirable. The resulting Gregorian calendar is the internationally accepted civil calendar used throughout the world today and is an important contribution of the Catholic Church to Western Civilisation.[167][168][169] It was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII, after whom the calendar was named, by a decree signed on 24 February 1582.[170] In 1789, the Vatican Observatory opened. It was moved to Castel Gandolfo in the 1930s and the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope began making observation in Arizona, USA, in 1995.[171]

Detail of the tomb of Pope Gregory XIII celebrating the introduction of the Gregorian Calendar.

Galileo facing the Roman Inquisition by Cristiano Banti (1857).

The famous astronomers Nicholas Copernicus, who put the sun at the centre of the heavens in 1543, and Galileo Galilei, who experimented with the new technology of the telescope and, with its aid declared his belief that Copernicus was correct – were both practising Catholics – indeed Copernicus was a catholic clergyman. Yet the church establishment at that time held to theories devised in pre-Christian Greece by Ptolemy and Aristotle, which said that the sky revolved around the earth. When Galileo began to assert that the earth in fact revolved around the sun, he therefore found himself challenging the Church establishment at a time where the Church hierarchy also held temporal power and was engaged in the ongoing political challenge of the rise of Protestantism. After discussions with Pope Urban VIII (a man who had written admiringly of Galileo before taking papal office), Galileo believed he could avoid censure by presenting his arguments in dialogue form – but the Pope took offence when he discovered that some of his own words were being spoken by a character in the book who was a simpleton and Galileo was called for a trial before the Inquisition.[172]

In this most famous example cited by critics of the Catholic Church's "posture towards science", Galileo Galilei was denounced in 1633 for his work on the heliocentric model of the solar system, previously proposed by the Polish clergyman and intellectual Nicolaus Copernicus. Copernicus's work had been suppressed de facto by the Church, but Catholic authorities were generally tolerant of discussion of the hypothesis as long as it was portrayed only as a useful mathematical fiction, and not descriptive of reality. Galileo, by contrast, argued from his unprecedented observations of the solar system that the heliocentric system was not merely an abstract model for calculating planetary motions, but actually corresponded to physical reality – that is, he insisted the planets really do orbit the Sun. After years of telescopic observation, consultations with the Popes, and verbal and written discussions with astronomers and clerics, a trial was convened by the Tribunal of the Roman and Universal Inquisition. Galileo was found "vehemently suspect of heresy" (not "guilty of heresy," as is frequently misreported), placed under house arrest, and all of his works, including any future writings, were banned.[173] Galileo had been threatened with torture and other Catholic scientists fell silent on the issue. Galileo's great contemporary René Descartes stopped publishing in France and went to Sweden. According to Polish-British historian of science Jacob Bronowski:[172]

| “ | The effect of the trial and imprisonment was to put a total stop to the scientific tradition in the Mediterranean. From now on the Scientific Revolution moved to Northern Europe. | ” |

Pope John Paul II, on 31 October 1992, publicly expressed regret for the actions of those Catholics who badly treated Galileo in that trial.[174][175] Cardinal John Henry Newman, in the nineteenth century, claimed that those who attack the Church can only point to the Galileo case, which to many historians does not prove the Church's opposition to science since many of the churchmen at that time were encouraged by the Church to continue their research.[176]

Evolution

Since the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859, the position of the Catholic Church on the theory of evolution has slowly been refined. For about 100 years, there was no authoritative pronouncement on the subject, though many hostile comments were made by local church figures. In contrast with many Protestant objections, Catholic issues with evolutionary theory have had little to do with maintaining the literalism of the account in the Book of Genesis, and have always been concerned with the question of how man came to have a soul. Modern Creationism has had little Catholic support. In the 1950s, the Church's position was one of neutrality; by the late 20th century its position evolved to one of general acceptance in recent years. However, the church insists that the human soul was immediately infused by God, and the reality of a single ancestor (commonly called monogenism) for the human race.[citation needed]

Today[update], the Church's official position is a fairly non-specific example of theistic evolution,[177][178] stating that faith and scientific findings regarding human evolution are not in conflict, though humans are regarded as a special creation, and that the existence of God is required to explain both monogenism and the spiritual component of human origins. No infallible declarations by the Pope or an Ecumenical Council have been made. The Catholic Church's official position is fairly non-specific, stating only that faith and the origin of man's material body "from pre-existing living matter" are not in conflict, and that the existence of God is required to explain the spiritual component of man's origin.[citation needed]

Many fundamentalist Christians, however, retain the belief that the Biblical account of the creation of the world (as opposed to evolution) is literal.[179]

Embryonic stem cell research

Recently, the Church has been criticized for its teaching that embryonic stem cell research is a form of experimentation on human beings, and results in the killing of a human person. Much criticism of this position has been on the grounds that the doctrine hinders scientific research; even some conservatives, taking a utilitarian position, have pointed out that most embryos from which stem cells are harvested are "leftover" from in vitro fertilization, and would soon be discarded whether used for such research or not. The Church, by contrast, has consistently upheld its ideal of the dignity of each individual human life, and argues that it is as wrong to destroy an embryo as it would be to kill an adult human being; and that therefore advances in medicine can and must come without the destruction of human embryos, for example by using adult or umbilical stem cells in place of embryonic stem cells.

Art, architecture, literature, and music

The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

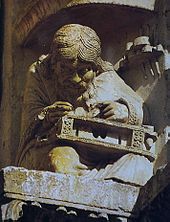

Saint Thomas Aquinas was one of the great scholars of the Medieval period.

An 18th-century Italian depiction of the Parable of the Good Samaritan. Biblical subjects have been a constant theme of Western art.

Ludwig van Beethoven, composed many Masses and religious works, including his Ninth Symphony Ode to Joy.

Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Muslim states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward. A number of states contemporary with the Byzantine Empire were culturally influenced by it, without actually being part of it (the "Byzantine commonwealth"). These included Bulgaria, Serbia, and the Rus, as well as some non-Orthodox states like the Republic of Venice and the Kingdom of Sicily, which had close ties to the Byzantine Empire despite being in other respects part of western European culture. Art produced by Eastern Orthodox Christians living in the Ottoman Empire is often called "post-Byzantine." Certain artistic traditions that originated in the Byzantine Empire, particularly in regard to icon painting and church architecture, are maintained in Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Russia and other Eastern Orthodox countries to the present day.

Several historians credit the Catholic Church for what they consider to be the brilliance and magnificence of Western art. "Even though the church dominated art and architecture, it did not prevent architects and artists from experimenting..."[55]:225 Historians refer to the western Church's consistent opposition to Byzantine iconoclasm, a movement against visual representations of the divine, and its insistence on building structures befitting worship. Important contributions include its cultivation and patronage of individual artists, as well as development of the Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance styles of art and architecture.[180] Renaissance artists such as Raphael, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Bernini, Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Tintoretto, Caravaggio, and Titian, were among a multitude of innovative virtuosos sponsored by the Church.[181]Augustine's repeated reference to Wisdom 11:20 (God "ordered all things by measure and number and weight") influenced the geometric constructions of Gothic architecture,[citation needed] the scholastics' intellectual systems called the Summa Theologiae which influenced the writings of Dante, its creation and sacramental theology which has developed a Catholic imagination influencing writers such as J. R. R. Tolkien[182] and William Shakespeare,[183] and of course, the patronage of the Renaissance popes for the great works of Catholic artists such as Michelangelo, Raphael, Bernini, Borromini and Leonardo da Vinci.

British art historian Kenneth Clark wrote that Western Europe's first "great age of civilisation" was ready to begin around the year 1000. From 1100, he wrote, monumental abbeys and cathedrals were constructed and decorated with sculptures, hangings, mosaics and works belonging one of the greatest epochs of art and providing stark contrast to the monotonous and cramped conditions of ordinary living during the period. Abbot Suger of the Abbey of St. Denis is considered an influential early patron of Gothic architecture and believed that love of beauty brought people closer to God: "The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material". Clarke calls this "the intellectual background of all the sublime works of art of the next century and in fact has remained the basis of our belief of the value of art until today".[74]

Later, during The Renaissance and Counter-Reformation, Catholic artists produced many of the unsurpassed masterpieces of Western art – often inspired by Biblical themes: from Michelangelo's David and Pietà sculptures, to Da Vinci's Last Supper and Raphael's various Madonna paintings. Referring to a "great outburst of creative energy such as took place in Rome between 1620 and 1660", Kenneth Clarke wrote:[74]

[W]ith a single exception, the great artists of the time were all sincere, conforming Christians. Guercino spent much of his mornings in prayer; Bernini frequently went into retreats and practised the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius; Rubens attended Mass every morning before beginning work. The exception was Caravaggio, who was like the hero of a modern play, except that he happened to paint very well.

This conformism was not based on fear of the Inquisition, but on the perfectly simple belief that the faith which had inspired the great saints of the preceding generation was something by which a man should regulate his life.

In music, Catholic monks developed the first forms of modern Western musical notation in order to standardize liturgy throughout the worldwide Church,[184] and an enormous body of religious music has been composed for it through the ages. This led directly to the emergence and development of European classical music, and its many derivatives. The Baroque style, which encompassed music, art, and architecture, was particularly encouraged by the post-Reformation Catholic Church as such forms offered a means of religious expression that was stirring and emotional, intended to stimulate religious fervor.[185]