Empress Myeongseong

| Empress Myeongseong 명성황후 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empress consort of Korea (posthumously) | |||||

| |||||

| Queen consort of Joseon | |||||

| Tenure | 20 March 1866 – 8 October 1895 | ||||

| Regent of Joseon | |||||

| Tenure | 6 July 1895 – 8 October 1895 | ||||

| Monarch | Gojong | ||||

| Tenure | 1 November 1873 – 1 July 1894 | ||||

| Monarch | Gojong | ||||

| Born | 19 October 1851 Yeoju, Kingdom of Joseon | ||||

| Died | 8 October 1895 (1895-10-09) (aged 43) Okhoru Pavilion, Gyeongbok Palace, Kingdom of Joseon | ||||

| Burial | Hongneung | ||||

| Spouse | King Gojong | ||||

| Issue | Emperor Sunjong | ||||

| |||||

| House | Yeoheung Min | ||||

| Father | Min Chi-Rok | ||||

| Mother | Lady Lee of the Hansan Lee clan | ||||

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 명성황후 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 明成皇后 |

| Revised Romanization | Myeongseong Hwanghu |

| McCune–Reischauer | Myŏngsŏng Hwanghu |

Empress Myeongseong or Empress Myung-Sung (19 October 1851 – 8 October 1895), known informally as Queen Min, was the first official wife of Gojong, the twenty-sixth king of Joseon and the first emperor of the Korean Empire.

The government of Meiji Japan (明治政府) considered Empress Myeongseong (明成皇后) an obstacle to its overseas expansion.[1] Efforts to remove her from the political arena, orchestrated through failed rebellions prompted by the father of King Gojong, the Heungseon Daewongun (an influential regent working with the Japanese), compelled her to take a harsher stand against Japanese influence.[2]

After Japan's victory in the First Sino-Japanese War, Joseon Korea came under the Japanese sphere of influence. The Empress advocated stronger ties between Korea and Russia in an attempt to block Japanese influence in Korea. Miura Gorō, the Japanese Minister to Korea at that time and a retired army lieutenant-general, backed the faction headed by the Daewongun, whom he considered to be more sympathetic to Japanese interests.

In the early morning of 8 October 1895, the Hullyeondae Regiment, loyal to the Daewongun, attacked the Gyeongbokgung, overpowering its Royal Guards. Hullyeondae officers, led by Lieutenant Colonel Woo Beomseon, then allowed a group of Japanese ronins, specifically recruited for this purpose to infiltrate and assassinate the Empress in the palace, under orders from Miura Gorō. The assassination of the Empress ignited outrage among other foreign powers.[3]

Domestically, the assassination prompted anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea with the "Short Hair Act Order" (단발령, 斷髮令), and some Koreans created the Eulmi Righteous Army and actively set up protests nationwide.[4] Following the Empress's assassination, Emperor Gojong and the crown prince (later Emperor Sunjong of Korea) fled to the Russian legation in 1896. This led to the general repeal of the Gabo Reform, which was controlled by Japanese influence.[4] In October 1897, King Gojong returned to Gyeongungung (modern-day Deoksugung). There, he proclaimed the founding of the Korean Empire.[4]

In South Korea, there has been renewed interest in Empress Myeongseong due to popular novels, a film, a TV drama and even a musical based on her life story.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 End of an era

1.2 A new queen

2 The beginnings

2.1 Court domination

2.2 The "Hermit Kingdom" emerges

3 A social revolution

3.1 The insurrection of 1882

3.2 The Mission to America

3.3 The reformist vs. the conservatives

4 The Innovator

4.1 Education

4.2 The press

4.3 Medicine, religion, and music

4.4 Military

4.5 Economy

5 Personal life

5.1 Early years

5.2 Later years

6 Assassination

6.1 An eye-witness account

6.2 Involved parties

6.3 Aftermath

6.4 Funeral procession and tomb

7 Current events

8 Family

9 Titles

10 Photographs and illustrations

10.1 Another photograph surfaces

10.2 Japanese illustration

11 In popular culture

11.1 Film and television

11.2 Musicals

12 See also

13 References

14 Further reading

15 External links

Background

End of an era

In 1864 Cheoljong of Joseon was dying, and there were no male heirs, the result of suspected foul play by the Andong Kim clan, an aristocratic clan that was particularly influential during the 19th century. The Andong Kim clan had risen to power through intermarriage with the royal House of Yi. Queen Cheorin, Cheoljong's consort and a member of the Andong Kim clan, claimed the right to choose the next king, although traditionally the most senior Queen Dowager had the official authority to select the new king. Chŏljong's cousin, Grand Royal Dowager Sinjeong, the widow of Heonjong of Joseon's father of the Pungyang Jo clan, who too had risen to prominence by intermarriage with the Yi family, currently held this title.

Queen Sinjeong saw an opportunity to advance the cause of the Pungyang Jo clan, the only true rival of the Andong Kim clan in Korean politics. As Cheoljong succumbed to his illness, the Grand Royal Dowager Queen was approached by Yi Ha-eung, a distant descendant of King Injo (r.1623–1649), whose father was made an adoptive son of Prince Eunsin, a nephew of King Yeongjo (r.1724–1776).

The branch that Yi Ha-eung's family belonged to was an obscure line of descendants of the Yi clan, which survived the often deadly political intrigue that frequently embroiled the Joseon court by forming no affiliation with any factions. Yi Ha-eung himself was ineligible for the throne due to a law that dictated that any possible heir had to be part of the generation after the most recent incumbent of the throne, but his second son Yi Myeongbok was a possible successor to the throne.

The Pungyang Jo clan saw that Yi Myeongbok was only 12 years old and would not be able to rule in his own name until he came of age, and that they could easily influence Yi Ha-eung, who would be acting as regent for his son. As soon as news of Cheoljong's death reached Yi Ha-eung through his intricate network of spies in the palace, he and the Pungyang Jo clan took the hereditary royal seal (considered necessary for a legitimate reign to take place and aristocratic recognition to be received), effectively giving Queen Sinjeong absolute power to select the successor to the throne. By the time Cheoljong's death became a known fact, the Andong Kim clan was powerless to act according to law because the seal already lay in the hands of Grand Royal Dowager Queen Sinjeong.

In the autumn of 1864, Yi Myeongbok was crowned as King Gojong of Joseon, with his father titled Heungseon Daewongun (Hangul: 대원군; Hanja: 大院君 "Grand Internal Prince").

The strongly Confucian Heungseon Daewongun proved to be a capable and calculating leader in the early years of Gojong's reign. He abolished the old government institutions that had become corrupt under the rule of various clans, revised the law codes along with the household laws of the royal court and the rules of court ritual, and heavily reformed the military techniques of the royal armies. Within a few short years he was able to secure complete control of the court, and eventually receive the submission of the Pungyang Jos while successfully disposing of the last of the Andong Kims, whose corruption, he believed, was responsible for the country's decline in the 19th century.

A new queen

The future queen-consort was born into the aristocratic Min family of the Yeoheung branch on 19 October 1851[5][6][7][8] in Yeoju, Gyeonggi Province, where the clan originated.[9]

The Yeoheung Mins were a noble clan boasting many highly positioned bureaucrats in its illustrious past, as well as two queen consorts, Queen Wongyeong, the wife of Taejong of Joseon, and Queen Inhyeon, the wife of Sukjong of Joseon.[9]

Before her marriage, the Empress was known as the daughter of Min Chirok (Hangul: 민치록; Hanja: 閔致祿). While some fictional accounts call her Min Jayeong, this name has not been confirmed by historical sources.[9] At the age of eight she had lost her father. Then, her mother, Lady Hanchang of the Yi clan (Hangul: 한산이씨), and she moved to the House of Gamgodang (감고당) and lived there until she moved to the palace and became Queen.[9]

When Gojong reached the age of 15, his father decided it was time for him to be married. The Daewongun was diligent in his search for a queen who would serve his purposes: she must have no close relatives who would harbor political ambitions, yet come from a noble lineage so as to justify his choice to the court and the people. Candidates were rejected one by one, until both the Daewongun's wife Yeoheung (Princess Consort to the Prince of the Great Court; Yeoheung Budaebuin; 여흥부대부인, 驪興府大夫人)[10] and his mother proposed a bride from their own clan, the Yeoheung Min.[9] The two women described the girl persuasively: she was orphaned and possessed beautiful features, a healthy body, and an ordinary level of education.[9]

The bride underwent a strict selection process, culminating in a meeting with the Daewongun on 6 March, and a marriage ceremony on 20 March 1866.[11] Min, barely 16, married the 15-year-old king and was invested in a ceremony (책비, chaekbi) as the Queen Consort of Joseon.[12] Two places assert claims on the marriage and ascension: both Injeong Hall (인정전) at Changdeok Palace[9] and Norak Hall (노락당) at Unhyeon Palace. The wig typically worn by brides at royal weddings was so heavy for the slight 16-year-old bride that a tall court lady was specially assigned to support it from the back. Directly following the wedding was the three-day ceremony for the reverencing of the ancestors.[13]

Older officials soon noticed that the new queen consort was an assertive and ambitious woman, unlike other queens preceding her. She did not participate in lavish parties, rarely commissioned extravagant fashions from the royal ateliers, and almost never hosted afternoon tea parties with the various princesses of the royal family or powerful aristocratic ladies unless politics required her to do so. While she was expected to act as an icon for Korea's high society, the queen rejected this role. Instead, she devoted time to reading books generally reserved for men (such as Spring and Autumn Annals and its accompanying Zuo Zhuan,[9]) and furthered her own education in history, science, politics, philosophy, and religion.

The beginnings

Court domination

By the age of twenty, the queen consort had begun to wander outside her apartments at Changgyeong Palace and to play an active part in politics in spite of the Daewongun and various high officials, who viewed her as becoming meddlesome. The political struggle between the queen consort and the Heungseon Daewongun became public when the son she bore died prematurely four days after birth. The Heungseon Daewongun publicly accused her of being unable to bear a healthy male child, while she suspected her father-in-law of foul play through the ginseng emetic treatment he had brought her.[14] The Daewongun then directed Gojong to conceive through a concubine, Lee Gwi-in from the Yeongbo Hall (영보당귀인 이씨), and on 16 April 1868, she gave birth to Prince Wanhwa (완화군), to whom the Daewongun gave the title of crown prince.

However, the queen consort had begun to secretly form a powerful faction against the Heungseon Daewongun, once she reached adulthood; now, with the backing of high officials, scholars, and members of her clan, she sought to remove the Heungseon Daewongun from power. Min Seung-ho, one of the queen consort's relatives, along with court scholar Choe Ik-hyeon, devised a formal impeachment of the Heungseon Daewongun to be presented to the Royal Council of Administration, arguing that Gojong, now 22, should rule in his own right. In 1872, with the approval of Gojong and the Royal Council, the Heungseon Daewongun was forced to retire to Unhyeongung, his estate at Yangju. The queen consort then banished the royal concubine along with her child to a village outside the capital, stripped of royal titles. The child soon died afterwards.

With these expulsions, the queen consort gained complete control over her court, and placed family members in high court positions. Finally, she was a queen consort who ruled along with her husband; moreover she was recognized as being distinctly more politically active than Gojong.

The "Hermit Kingdom" emerges

After Korean refusal to receive Japanese envoys announcing the Meiji Restoration, some Japanese aristocrats favored an immediate invasion of Korea, but the idea was quickly dropped upon the return of the Iwakura Mission on the grounds that the new Japanese government was neither politically nor fiscally stable enough to start a war. When Heungseon Daewongun was ousted from politics, Japan renewed efforts to establish ties with Korea, but the Imperial envoy arriving at Dongnae in 1873 was turned away.

The Japanese government, which sought to emulate the empires of Europe in their tradition of enforcing so-called Unequal Treaties, responded by sending the Japanese gunboat Unyō towards Busan and another warship to the Bay of Yeongheung on the pretext of surveying sea routes, meaning to pressure Korea into opening its doors. The Unyō ventured into restricted waters off Ganghwa Island, provoking an attack from Korean shore batteries. The Unyō fled but the Japanese used the incident as a pretext to force a treaty on the Korean government. In 1876 six naval vessels and an imperial Japanese envoy were sent to Ganghwa Island to enforce this command.

A majority of the royal court favored absolute isolationism, but Japan had demonstrated its willingness to use force. After numerous meetings, officials were sent to sign the Ganghwa Treaty, a treaty that had been modeled after treaties imposed on Japan by the United States. The treaty was signed on 15 February 1876, thus opening Korea to Japan and the world.

Various ports were forced to open to Japanese trade, and Japanese now had rights to buy land in designated areas. The treaty also permitted the opening of the major ports, Incheon and Wonsan to Japanese merchants. For the first few years, Japan enjoyed a near total monopoly of trade, while Korean merchants suffered serious losses.

A social revolution

In 1877, a mission headed by Kim Gi-su was commissioned by Gojong and Min to study Japanese westernization and its intentions for Korea.

In 1881 another mission, this one under Kim Hongjip went to Japan. Kim and his team were shocked at how large the Japanese cities had become. He noted that only 50 years before, Seoul and Busan of Korea were metropolitan centers of East Asia, dominant over underdeveloped Japanese cities; but now, in 1877, with Tokyo and Osaka westernized throughout the Meiji Restoration, Seoul and Busan looked like vestiges of the ancient past.

When they were in Japan, Kim met with the Chinese ambassador to Tokyo, Ho Ju-chang and the councilor Huang Tsun-hsien. They discussed the international situation of Qing China and Joseon's place in the rapidly changing world. Huang Tsu-hsien presented to Kim a book he had written called Korean Strategy.

China was no longer the hegemonic power of East Asia, and Korea no longer enjoyed military superiority over Japan. In addition, the Russian Empire began expansion into Asia. Huang advised that Korea should adopt a pro-Chinese policy, while retaining close ties with Japan for the time being. He also advised an alliance with the United States for protection against Russia. He advised opening trade relations with Western nations and adopting Western technology. He noted that China had tried but failed due to its size, but Korea was smaller than Japan. He viewed Korea as a barrier to Japanese expansion into mainland Asia. He suggested Korean youths be sent to China and Japan to study, and Western teachers of technical and scientific subjects be invited to Korea.

When Kim returned to Seoul, Queen Min took special interest in Huang's book and commissioned copies be sent out to all the ministers. She had hoped to win yangban (aristocratic) approval to invite Western nations into Korea, to open up trade with and keep Japan in check. She wanted to first allow Japan to help in the modernization process but towards completion of certain projects, have them be driven out by Western powers.

However, the yangban aristocracy still opposed opening the country to the West. Choi Ik-hyun, who had helped with the impeachment of Heungseon Daewongun, sided with the isolationists, saying that the Japanese were just like the "Western barbarians" who would spread subversive notions like Catholicism (which had been a major issue during Heungseon Daewongun's reign and had been quashed by massive persecutions).

To the socially conservative yangban, Queen Min's plan meant the destruction of social order. The response to the distribution of "Korean Strategy" was a joint memorandum to the throne from scholars in every province of the kingdom. They stated that the ideas in the book were mere abstract theories, unrealizable in practice, and that the adoption of Western technology was not the only way to enrich the country. They demanded that the number of envoys exchanged, ships engaged in trade and articles of trade be strictly limited, and that all foreign books in Korea should be destroyed.

Despite these objections, in 1881, a large fact-finding mission was sent to Japan to stay for seventy days observing Japanese government offices, factories, military and police organizations, and business practices. They also obtained information about innovations in the Japanese government copied from the West, especially the proposed constitution.

On the basis of these reports, the Queen Consort began the reorganization of the government. Twelve new bureaus were established that dealt with foreign relations with the West, China, and Japan. Other bureaus were established to effectively deal with commerce. A bureau of the military was created to modernize weapons and techniques. Civilian departments were also established to import Western technology.

In the same year, the Queen Consort signed documents, arranging for top military students to be sent to Qing China. The Japanese quickly volunteered to supply military students with rifles and train a unit of the Korean army to use them. She agreed but reminded the Japanese that the students would still be sent to China for further education on Western military technologies.

The modernization of the military was met with opposition. The special treatment of the new training unit caused resentment among the other troops. In September 1881, a plot was uncovered to overthrow the Queen Consort’s faction, depose the King, and place Heungseon Daewongun's illegitimate (third) son, Yi Jae-seon on the throne. The plot was frustrated by the Queen Consort but Heungseon Daewongun was kept safe from persecution because he was still the father of the King.

The insurrection of 1882

In 1882, members of the old military became resentful of the special treatment of the new units and so attacked and destroyed the house of Min Gyeom-ho, a relative of the Queen Consort, who was the administrative head of the training units. These soldiers then fled to the protection of the Heungseon Daewongun, who publicly rebuked but privately encouraged them. The Heungseon Daewongun then took control of the old units.

He ordered an attack on the administrative district of Seoul that housed the Gyeongbokgung, the diplomatic quarter, military centers, and science institutions. The soldiers attacked police stations to free comrades who had been arrested and then began ransacking private estates and mansions belonging to relatives of the Queen Consort. These units then stole rifles and began to kill Japanese training officers, and narrowly missed killing the Japanese ambassador to Seoul, who quickly escaped to Incheon. The military rebellion then headed towards the palace but both Queen Consort and the King escaped in disguise and fled to her relative’s villa in Cheongju, where they remained in hiding.

Numerous supporters of the Queen Consort were put to death as soon as the Daewongun arrived and took administrative control of Gyeongbokgung Palace. He immediately dismantled the reform measures implemented by the Queen Consort and relieved the new units of their duties. Foreign policy quickly returned to isolationism, and Chinese and Japanese envoys were forced out of the capital.

Li Hung-chang, with the consent of Korean envoys in Beijing, sent 4,500 Chinese troops to restore order, as well as to secure Chinese interests in the country. The troops arrested the Heungseon Daewongun, who was then taken to China to be tried for treason. The royal couple returned and overturned all of the Daewongun's actions.

The Japanese forced King Gojong privately, without Queen Min's knowledge, to sign the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1882 on 10 August 1882, to pay 550,000 yen for lives and property that the Japanese had lost during the insurrection, and permit Japanese troops to guard the Japanese embassy in Seoul. When the Queen Consort learned of the treaty, she proposed to China a new trade agreement, granting the Chinese special privileges and rights to ports inaccessible to the Japanese. She also requested that a Chinese commander take control of the new military units and a German adviser named Paul Georg von Möllendorff to head the Maritime Customs Service.

The Mission to America

In September 1883, the Queen Consort established English language schools with American instructors. She sent a special mission in July 1883 to the United States, headed by Min Yeong-ik, one of her relatives. The mission arrived at San Francisco carrying the newly created Korean national flag, visited many American historical sites, heard lectures on American history, and attended a gala event in their honor given by the mayor of San Francisco and other U.S. officials. The mission dined with President Chester A. Arthur, and discussed the growing threat of Japanese and American investment in Korea. At the end of September, Min Yeong-ik returned to Seoul and reported to the Queen Consort,

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

I was born in the dark. I went out into the light, and, your Majesty, it is my displeasure to inform you that I have returned to the dark. I envision a Seoul of towering buildings filled with Western establishments that will place herself back above the Japanese barbarians. Great things lie ahead for this Kingdom, great things. We must take action, your Majesty, without hesitation, to further modernize this still ancient kingdom.

The reformist vs. the conservatives

The Progressives were founded during the late 1870s by a group of yangban who fully supported Westernization of Joseon. However, they wanted immediate Westernization, including a complete cut-off of ties with Qing China. Unaware of their anti-Chinese sentiments, the Queen Consort granted frequent audiences and meetings with them to discuss progressivism and nationalism. They advocated for educational and social reforms, including the equality of the sexes by granting women full rights, issues that were not even acknowledged in their already Westernized neighbor of Japan. The Queen Consort was completely enamored by the Progressives in the beginning, but when she learned that they were deeply anti-Chinese, she quickly turned her back on them. Cutting ties with China immediately was not in her gradual plan of Westernization. She saw the consequences Joseon would have to face if she did not play China and Japan off by the West gradually, especially since she was a strong advocate of the Sadae faction who were pro-China and pro-gradual Westernization.

However, in 1884, the conflict between the Progressives and the Sadaes intensified. When American legation officials, particularly Naval Attaché George C. Foulk, heard about the growing problem, they were outraged and reported directly to the Queen Consort. The Americans attempted to bring the two groups to peace with each other in order to aid the Queen Consort in a peaceful transformation of Joseon into a modern nation. After all, she liked the ideas and plans of both parties. As a matter of fact, she was in support of many of the Progressive's ideas, except for severing relations with China.

However, the Progressives, fed up with the Sadaes and the growing influence of the Chinese, sought the aid of the Japanese legation guards and staged a bloody palace coup on 4 December 1884. The Progressives killed numerous high Sadaes and secured key government positions vacated by the Sadaes who had fled the capital or had been killed.

The refreshed administration began to issue various edicts in both the King and Queen Consort's names and they were eager to implement political, economic, social, and cultural reforms. However, the Empress was horrified by the bellicosity of the Progressives and refused to support their actions and declared any documents signed in her name to be null and void. After only two days of new influence over the administration, they were crushed by Chinese troops under Yuan Shih-kai's command. A handful of Progressive leaders were killed. Once again, the Japanese government saw the opportunity to extort money out of the Joseon government by forcing Gojong, again without the knowledge of his wife, to sign a treaty. The Treaty of Hanseong forced Joseon to pay a large sum of indemnity for damages inflicted on Japanese lives and property during the coup.

On 18 April 1885 the Li-Ito Agreement was made in Tianjin, China, between the Japanese and the Chinese. In it, they both agreed to pull troops out of Joseon and that either party would send troops only if their property was endangered and that each would inform the other before doing so. Both nations also agreed to pull out their military instructors to allow the newly arrived Americans to take full control of that duty. The Japanese withdrew troops from Korea, leaving a small number of legation guards, but the Queen Consort was ahead of the Japanese in their game. She summoned Chinese envoys and through persuasion, convinced them to keep 2,000 soldiers disguised as Joseon police or merchants to guard the borders from any suspicious Japanese actions and to continue to train Korean troops.

The Innovator

Education

Peace finally settled upon the once-renowned "Land of the Morning Calm." With the majority of Japanese troops out of Joseon and Chinese protection readily available, the plans for further, drastic modernization were continued. Plans to establish a palace school to educate children of the elite had been in the making since 1880 but were finally executed in May 1885 with the approval of the Queen Consort. A palace school named "Yugyoung Kung-won" (육영공원, 育英公院, Royal English School) was established, with an American missionary, Homer B. Hulbert, and three other missionaries to lead the development of the curriculum. The school had two departments, liberal education and military education. Courses were taught exclusively in English using English textbooks. However, due to low attendance, the school was closed shortly after the last English teacher, Bunker, resigned in late 1893.[15]

The Queen Consort also gave her patronage to the first all-girls' educational institution, Ewha Academy, established in Seoul, 1886 by American missionary, Mary F. Scranton (later became the Ewha University). In reality, as Louisa Rothweiler, a founding teacher of Ewha Academy observed, the school was, at its early stage, more of a place for poor girls to be fed and clothed than a place of education.[15] This was a significant social change.[16] The institution survives to this day as the Ewha Woman's University - one of the Republic of Korea's top private universities and still an all-girl's school.

The Protestant missionaries contributed much to the development of Western education in Joseon Korea. The Queen Consort, unlike her father-in-law, who had oppressed Christians, invited different missionaries to enter Joseon. She knew and valued their knowledge of Western history, science, and mathematics, and was aware of the advantage of having them within the nation. Unlike the Isolationists, she saw no threat to the Confucian morals of Korean society in the advent of Christianity.[citation needed] Religious tolerance was another one of her goals.

The press

The first newspaper to be published in Joseon was the "Hanseong Sunbo", an all-Hanja newspaper. It was published as a thrice monthly official government gazette by the Bakmun-guk (Publishing house), an agency of the Foreign Ministry. It included contemporary news of the day, essays and articles about Westernization, and news of further modernization of Joseon.

In January 1886, the Bakmun-guk published a new newspaper named the Hanseong Jubo (The Seoul Weekly). The publication of a Korean-language newspaper was a significant development, and the paper itself played an important role as a communication media to the masses until it was abolished in 1888 under pressure from the Chinese government.

A newspaper in entirely Hangul, disregarding the Korean Hanja script, was not published again until 1894. Ganjo Sinbo (The Seoul News) was published as a weekly newspaper under the patronage of both Gojong and the Queen Consort, it was written half in Korean and half in Japanese.

Medicine, religion, and music

The arrival of Horace Newton Allen under invitation of the Queen Consort in September 1884 marked the formal introduction of Christianity, which spread rapidly in Joseon. He was able, with the Queen Consort's permission and official sanction, to arrange for the appointment of other missionaries as government employees. He also introduced modern medicine in Korea by establishing the first western Royal Medical Clinic of Gwanghyewon in February 1885.[17]

In April 1885, a horde of Protestant missionaries began to flood into Joseon. The Isolationists were horrified and realized they had finally been defeated by the Queen Consort. The doors to Korea were not only open to ideas, technology, and culture but also to other religions. Having lost immense power with Heungseon Daewongun (still captive in China), the Isolationists could do nothing but simply watch. Horace Grant Underwood and his wife, William B. Scranton, his wife, and his mother, Mary Scranton, made Korea their new home in May 1885. They established churches within Seoul and began to establish centers in the countrysides. Catholic missionaries arrived soon afterwards, reviving Catholicism which had witnessed massive persecution in 1866 under Heungseon Daewongun's rule.

While winning many converts, Christian missionaries made significant contributions towards the modernization of the country. Concepts of equality, human rights and freedom, and the participation of both men and women in religious activities were all new to Joseon. The Queen Consort was ecstatic at the prospect of integrating these values within the government. She had wanted the literacy rate to rise, and with the aid of Christian educational programs, it did so significantly within a matter of a few years.

Drastic changes were made to music as well. Western music theory partly displaced the traditional Eastern concepts. The Protestant missions introduced Christian hymns and other Western songs that created a strong impetus to modernize Korean ideas about music. The organ and other Western musical instruments were introduced in 1890, and a Christian hymnal was published in the Korean language in 1893 under the commission of the Queen Consort. She herself, however, never became a Christian, but remained a devout Buddhist with influences from shamanism and Confucianism; her religious beliefs would become the model, indirectly, for those of many modern Koreans, who share her belief in pluralism and religious tolerance.

Military

Modern weapons were imported from Japan and the United States in 1883. The first military factories were established and new military uniforms were created in 1884. Under joint patronage of Gojong & his Queen Consort, a request was made to the United States for more American military instructors to speed up the military modernization of Korea. Out of all the projects that were going on simultaneously, the military project took the longest.

In October 1883, American minister Lucius Foote arrived to take command of the modernization of Joseon's older army units that had not started Westernizing. In April 1888, General William McEntyre Dye and two other military instructors arrived from the United States, followed in May by a fourth instructor. They brought about rapid military development.

A new military school was created called "Yeonmu Gongwon", and an officers training program began. However, despite armies becoming more and more on par with the Chinese and the Japanese, the idea of a navy was neglected. As a result, it became one of the few failures of the modernization project. Due to the neglect of developing naval defence, Joseon's long sea borders were open to invasion. It was an ironic mistake since nearly 300 years earlier, Joseon's navy was the strongest in all of East Asia[citation needed]. Now, the Korean navy was nothing but ancient ships that could barely defend themselves from the advanced ships of modern navies.

However, for a short while, hope for the Korean military could be seen. With rapidly growing armies, Japan itself was becoming fearful of the impact of Korean troops if her government did not interfere soon to stall the process.

Economy

Following the opening of all Korean ports to the Japanese and Western merchants in 1888, contact and involvement with outsiders increased foreign trade rapidly. In 1883, the Maritime Customs Service was established under the patronage of the Queen Consort and the supervision of Sir Robert Hart, 1st Baronet of the United Kingdom. The Maritime Customs Service administered the business of foreign trade and collection of tariffs.

By 1883, the economy was now no longer in a state of monopoly conducted by Japanese merchants as it had been only a few years ago. The majority was in control by the Koreans while portions were distributed between Western nations, Japan and China. In 1884, the first Korean commercial firms such as the Daedong and the Changdong Company emerged. The Bureau of Mint also produced a new coin called "tangojeon" in 1884, securing a stable Korean currency at the time. Western investment began to take hold as well in 1886.

The German A.H. Maeterns, with the aid of the United States Department of Agriculture, created a new project called "American Farm" on a large plot of land donated by the Queen Consort to promote modern agriculture. Farm implements, seeds, and milk cows were imported from the United States. In June 1883, the Bureau of Machines was established and steam engines were imported. However, despite the fact that Gojong and his Queen Consort brought the Korean economy to an acceptable level to the West, modern manufacturing facilities did not emerge due to a political interruption: the assassination of the Queen Consort. Be that as it may, telegraph lines between Joseon, China, and Japan were laid between 1883 and 1885, facilitating communication.

Personal life

Early years

Detailed descriptions of Min can be found in both The National Assembly Library of Korea and records kept by Lilias Underwood,[18] a close and trusted American friend of Min who came to Korea in 1888 as a missionary and was appointed as her doctor.

Both sources describe the Empress' appearance, voice, and public manner. She was said to have had a soft face with strong features—a classic beauty contrasting with the king's preference for "sultry" women. Her personal speaking voice was soft and warm, but when conducting affairs of the state, she asserted her points with strength. Her public manner was formal, and she heavily adhered to court etiquette and traditional law. Underwood described the Empress in the following:[19]

I wish I could give the public a true picture of the queen as she appeared at her best, but this would be impossible, even had she permitted a photograph to be taken, for her charming play of expression while in conversation, the character and intellect which were then revealed, were only half seen when the face was in repose. She wore her hair like all Korean ladies, parted in the center, drawn tightly and very smoothly away from the face and knotted rather low at the back of the head. A small ornament...was worn on the top of the head fastened by a narrow black band...

Her majesty seemed to care little for ornaments, and wore very few. No Korean women wear earrings, and the queen was no exception, nor have I ever seen her wear a necklace, a brooch, or a bracelet. She must have had many rings, but I never saw her wear more than one or two of European manufacture...

According to Korean custom, she carried a number of filigree gold ornaments decorated with long silk tassels fastened at her side. So simple, so perfectly refined were all her tastes in dress, it is difficult to think of her as belonging to a nation called half civilized...

Slightly pale and quite thin, with somewhat sharp features and brilliant piercing eyes, she did not strike me at first sight as being beautiful, but no one could help reading force, intellect and strength of character in that face...

The young queen consort and her husband were incompatible in the beginning of their marriage. Both found the other's ways repulsive; she preferred to stay in her chambers studying, while he enjoyed spending his days and nights drinking and attending banquets and royal parties. The queen, who was genuinely concerned with the affairs of the state and immersed herself in philosophy, history, and science books normally reserved for yangban men, once remarked to a close friend, "He disgusts me."

Court officials noted that the queen consort was exclusive in choosing who she associated with and confided in. She chose to not consummate her marriage on her wedding night as court tradition dictated her to,[citation needed] but later had immense difficulty in conceiving a healthy heir. Her first pregnancy five years after marriage ended in despair and humiliation when her infant son died shortly after birth.[citation needed] Her second son, Sunjong, was never a healthy child, often catching illnesses and convalescing in bed for weeks.[citation needed] While Min was unable to truly connect with Gojong in the early years, trials during their later marriage brought them together.[citation needed]

Later years

The national funeral march for Empress Myeongseong two years after her assassination in 1895

Both the Gojong and his Queen began to grow affections for each other during their later years. Gojong was pressured by his advisers to take control of the government and administer his nation. However, one has to remember that Gojong was not chosen to become King because of his acumen (which he lacked because he was never formally educated) or because of his bloodline (which was mixed with courtesan and common blood), but because the Pungyang Jo clan had falsely assumed they could control the boy through his father. When it was actually time for Gojong to assume his responsibilities of the state, he often needed the aid of his wife to conduct international and domestic affairs. In this, Gojong grew an admiration for his wife's wit, intelligence, and ability to learn quickly. As the problems of the kingdom grew bigger and bigger, Gojong relied even more on his wife, she becoming his rock during times of frustration.

During the years of modernization of Joseon, it is safe to assume that Gojong was finally in love with his wife. They began to spend much time with each other, privately and officially. They shared each other's problems, celebrated each other's joys, and felt each other's pains. They finally became husband and wife.

His affection for her was undying, and it has been noted that after the death of his Queen Consort, Gojong locked himself up in his chambers for several weeks, refusing to assume his duties. When he finally did, he lost the will to even try and signed treaty after treaty that was proposed by the Japanese, giving the Japanese immense power. When his father regained political power after the death of his daughter-in-law, he presented a proposal with the aid of certain Japanese officials to lower his daughter-in-law's status as Queen Consort all the way to commoner posthumously. Gojong, a man who had always been used by others and never used his own voice for his own causes, was noted by scholars as having said, "I would rather slit my wrists and let them bleed than disgrace the woman who saved this kingdom." In an act of defiance, he refused to sign his father's and the Japanese proposal, and turned them away.

Assassination

Okhoru Pavilion in Geoncheongjeon, Gyeongbokgung where the Empress was killed.

The Empress' assassination, known in Korea as the Eulmi Incident (을미사변, 乙未事變), occurred in the early hours of 8 October 1895 at Okho-ru (옥호루, 玉壺樓) in the Geoncheonggung (건청궁, 乾淸宮), which was the rear private royal residence inside Gyeongbokgung Palace.[20]

In the early hours of 8 October, Japanese agents under Miura Goro carried out the assassination. Miura had orchestrated this incident with Okamoto Ryūnosuke (岡本柳之助), Sugimura Fukashi (杉村 濬), Kunitomo Shigeaki (國友重章), Sase Kumatetsu (佐瀨熊鐵), Nakamura Tateo (中村楯雄), Hirayama Iwahiko (平山岩彦), and over fifty other Japanese men. Said to have collaborated in this were the pro-Japanese officers Lieutenant Colonel Woo Beom-seon (우범선, 禹範善) and Lieutenant Colonel Yi Du-hwang (이두황, 李斗璜) both battalion commanders in the "Hullyeondae," a Japanese trained Regiment of the Royal Guards.[20] The 1,000 Korean soldiers of the Hullyeondae, led by Lieutenant Colonel Woo Beom-seon[21][unreliable source] and Lieutenant Colonel Yi Du-hwang had surrounded and opened the gates of the palace, allowing a group of Japanese ronin to enter the inner sanctum.

In front of Gwanghwamun, the Hullyeondae soldiers led by Woo Beom-seon[21][unreliable source] battled the Korean Royal Guards led by Hong Gye-hun (홍계훈, 洪啓薰) and An Gyeong-su (안경수, 安駉壽).[20]Hong Gye-hun and Minister Yi Gyeong-jik (이경직, 李耕稙) were subsequently killed in battle, allowing the ronin assassins to proceed to Okhoru (옥호루, 玉壺樓), within Geoncheonggung, and kill the Empress. The corpse of the Empress was then burned and buried.[20]

Historian of Japan Peter Duus has called this assassination a "hideous event, crudely conceived and brutally executed."[22]Donald Keene, who calls the queen "an arrogant and corrupt woman", says that the way in which she was murdered was nonetheless "unspeakably barbaric."[23]

An eye-witness account

Alleged killers of Queen Min posing in front of Hanseong sinbo building in Seoul (1895)

Crown Prince Sunjong reported that he saw Korean troops led by Woo Beom-seon at the site of the assassination, and accused Woo as the "Foe of Mother". In addition to his accusation, Sunjong sent two assassins to kill Woo, an effort that succeeded in Hiroshima, Japan, in 1903. By then, Woo had married a Japanese woman, and had sired Woo Jang-choon (禹長春 우장춘), later to become an acclaimed botanist and agricultural scientist.

In 2005, professor Kim Rekho (김려춘; 金麗春) of the Russian Academy of Sciences came across a written account of the incident by a Russian architect Afanasy Seredin-Sabatin (Афанасий Иванович Середин-Сабатин) in the Archive of Foreign Policy of the Russian Empire (Архив внешней политики Российской империи; AVPRI).[24] Seredin-Sabatin was in the service of the Korean government, working with the American general William McEntyre Dye who was also under contract to the Korean government. In April, Kim made a request to the Myongji University (명지대학교; 明知大學校) Library LG Collection to make the document public. On 11 May 2005 the document was made public.

Almost five years before the document's release in South Korea, a translated copy was in circulation in the United States, having been released by the Center for Korean Research of Columbia University on 6 October 1995 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Eulmi Incident.[25]

In the account, Seredin-Sabatin recorded:

The courtyard where the Queen (Consort)'s wing was located was filled with Japanese, perhaps as many as 20 or 25 men. They were dressed in peculiar gowns and were armed with sabres, some of which were openly visible. ... While some Japanese troops were rummaging around in every corner of the palace and in the various annexes, others burst into the queen's wing and threw themselves upon the women they found there. ... I ... continued to observe the Japanese turning things inside out in the queen's wing. Two Japanese grabbed one of the court ladies, pulled her out of the house, and ran down the stairs dragging her along behind them. ... Moreover one of the Japanese repeatedly asked me in English, "Where is the queen? Point the queen out to us!" ... While passing by the main Throne Hall, I noticed that it was surrounded shoulder to shoulder by a wall of Japanese soldiers and officers, and Korean mandarins, but what was happening there was unknown to me.[26]

Involved parties

In Japan, 56 men were charged. All were acquitted by the Hiroshima court due to a lack of evidence.[27]

They included[28]

- Viscount Miura Gorō, Japanese legation minister.

Okamoto Ryūnosuke (岡本柳之助), a legation official[29] and former Japanese Army officer- Hozumi Torakurō, Kokubun Shōtarō, Hagiwara Shujiro, Japanese legation officials[29]

Sugimura Fukashi (杉村 濬),[30] a second Secretary of the Japanese legation[31]

Adachi Kenzo, editor of Japanese newspaper in Korea, Kanjō Shimpō[32] (漢城新報, also called Hanseong Shinbo in Korean)

Kusunose Yukihiko, a general of Imperial Japanese Army

Kunitomo Shigeaki (國友重章),[33] one of the original Seikyōsha (Society for Political Education) members[34]

Shiba Shirō[30] (柴四朗), private secretary to the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce of Japan, and writer who studied political economy at the Wharton School and Harvard University[35]

- Sase Kumatetsu (佐瀨熊鐵), a physician[35]

- Terasaki Yasukichi (寺崎泰吉), a medicine peddler[36]

Nakamura Tateo (中村楯雄)

Horiguchi Kumaichi (堀口 九萬一)

Ieiri Kakitsu (家入嘉吉)

Kikuchi Kenjō (菊池 謙讓)

Hirayama Iwahiko (平山岩彦)

Ogihara Hidejiro (荻原秀次郎)

Kobayakawa Hideo (小早川秀雄), editor in chief of Kanjō Shimpō[37]

- Sasaki Masayuki

Isujuka Eijoh[38][full citation needed]

and others.

In Korea, King Gojong declared that the following were the Eulmi Four Traitors on 11 February 1896:

Jo Hui-yeon (趙羲淵 조희연)

Yoo Gil-joon (兪吉濬 유길준)

Kim Hong-jip (金弘集 김홍집)

Jeong Byeong-ha (鄭秉夏 정병하)

Aftermath

The Gabo Reform and the assassination of Empress Myeongseong generated backlash against Japanese presence in Korea; it caused some Confucian scholars, as well as farmers, to form over 60 successive righteous armies to fight for Korean freedom on the Korean peninsula. The assassination is also credited as a significant event in the life of Syngman Rhee, the future first president South Korea.

The assassination of Empress Myeongseong, and the subsequent backlash, played a role in the assassination of influential statesman and Prince Itō Hirobumi. Itō Hirobumi was a four-time Prime Minister of Japan, former Resident-General of Korea, and then President of the Privy Council of Japan. Empress Myeongseong's assassination was the first of 15 reasons given by the Korean-independence assassin An Jung-geun, who is regarded as a hero in Korea, in defense of his actions.[39]

After the assassination, King Gojong and the Crown Prince (later Emperor Sunjong) fled for refuge to the Russian legation on 11 February 1896. Also, Gojong declared the Eulmi Four Traitors. However, In 1897, Gojong, yielding to rising pressure from both overseas and the demands of the Independence Association-led public opinion, returned to Gyeongungung (modern-day Deoksugung). There, he proclaimed the founding of the Korean Empire. However, after Japan's victories in the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars, Korea succumbed to Japanese colonial rule in 1910.

Funeral procession and tomb

1895 Funeral of Empress Myeongseong

In 1897, King Gojong, with Russian support, regained his throne, and spent "a fortune" to have his beloved Queen Min's remains properly honored and entombed. Her mourning procession included 5,000 soldiers, 650 police, 4,000 lanterns, hundreds of scrolls honoring her, and giant wooden horses intended for her use in the afterlife. The honors King Gojong placed on Queen Min for her funeral was meant as a statement to her diplomatic and heroic endeavors for Korea against the Japanese, as well as a statement of his own undying love for her. Queen Min's recovered remains are in her tomb located in Namyangju, Gyeonggi, South Korea.[38][full citation needed]

Current events

In May 2005, 84-year-old Tatsumi Kawano (川野 龍巳), the grandson of Kunitomo Shigeaki, paid his respects to Empress Myeongseong at her tomb in Namyangju, Gyeonggi, South Korea.[35][40] He apologized to Empress Myeongseong's tomb on behalf of his grandfather.[35]

Since 2009, Korean organizations have been trying to sue the Japanese government for their documented complicity in the murder of Queen Min. "Japan has not made an official apology or repentance 100 years after it obliterated the Korean people for 35 years through the 1910 Korea-Japan Annexation Treaty," the statement said. The lawsuit will be filed if the Japanese government does not accept their demands that the Japanese government issue a special statement on 15 August offering the emperor's apology and mentioning whether it will release related documents on the murder case.[41]

Family

- Great-Great-Great-Great-Grandfather

- Min Gwang-hun (Hangul: 민광훈, Hanja: 閔光勳) (1595–1659), scholar during the reign of King Injong.

- Great-Great-Great-Great-Grandmother

- Lady Yi (이씨, 李氏), daughter of Yi Gwang-jeong (이광정, 李光庭).

- Great-Great-Great-Great-Grandfather

- Min Yu-jung (민유중, 閔維重) (1630–1687).

- Great-Great-Great-Great-Grandmother

- Lady Song (송씨, 宋氏); Min Yu-jung's second wife; daughter of Song Jun-gil (송준길, 宋俊吉), Yeonguijeong during the reign of King Hyojong.

- Great-Great-Great-Grandfather

- Min Jin-hu (민진후, 閔鎭厚) (1659–1720), eldest brother of Queen Inhyeon (second consort of King Sukjong).

- Great-Great-Grandfather

- Min Ik-su (민익수, 閔浸沒) (1690–1742).

- Great-Grandfather

- Min Baek-bun (민백분, 閔百奮) (1723–?).

- Grandfather

- Min Gi-hyeon (민기현, 閔耆顯) (1751–1811).

- Father

- Min Chi-rok (민치록, 閔致祿) (1799–1858).

- Mother

- Lady Hanchang of Yi clan (한창부 부인 이씨) (본관: 한산 이씨, 이규년의 딸), Min Chi-rok's second wife.

- Husband

King Gojong (later Emperor Gojong).

- Sons

- Unnamed son (born 1871).

Emperor Sunjong (25 March 1874 – 24 April 1926).- Unnamed son (born 1875).

- Unnamed son (born 1878).

- Daughter

- Unnamed daughter (born 1873).

Titles

Throughout her life, Queen Min held several titles: as a member of the yangban aristocracy, as Queen Consort, and as regent of Korea. More titles were granted to her posthumously and after the creation of the Korean Empire. This includes the name by which she is best known by today, Empress Myeongseong.

19 October 1851 – 20 March 1866: Lady Min, the daughter of Min Chi-rok, of the Yeoheung Min clan

- "Lady Min"

- "The daughter of Min Chi-rok"

20 March 1866 – 1 November 1873: Her Majesty, the Queen Consort of Joseon

1 November 1873 – 1 July 1894: Her Majesty, the Queen Regent of Joseon

1 July 1894 – 6 July 1895: Her Majesty, the Queen Consort of Joseon

6 July 1895 – 8 October 1895: Her Majesty, the Queen Regent of Joseon

(The above four titles and styles were 王妃殿下 왕비전하 wangbi jeonha / 中殿媽媽 중전마마 jungjeon mama / 中宮殿媽媽 중궁전마마 junggungjeon mama applicable.)

- Empress Myeongseong of Korea (posthumous title)

Photographs and illustrations

Japanese illustration of King Gojong and Queen Min receiving Inoue Kaoru

Documents note that she was in an official royal family photograph. A royal family photograph does exist, but it was taken after her death, consisting of Gojong, Sunjong, and Sunjong's wife the Princess Consort of the Crown Prince.

Another photograph surfaces

There was a report by KBS News in 2003 that a photograph allegedly of the Empress had been disclosed to the public.[42] The photograph was supposedly purchased for a large sum by the grandfather of Min Soo-gyeong that was to be passed down as a family treasure. In the photo, the woman is accompanied by a retinue at her rear. Some experts have stated that the woman was clearly of high-rank and her clothing appears to be that that is worn only by the royal family. However, her outfit lacked the embroideries that decorates the apparel of the empress.[citation needed]

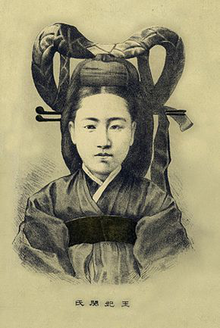

Japanese illustration

On 13 January 2005, history professor Lee Tae-jin (이태진, 李泰鎭) of Seoul National University unveiled an illustration from an old Japanese magazine he had found at an antique bookstore in Tokyo. The 84th edition of the Japanese magazine Fūzokugahō (風俗畫報) published on 25 January 1895 has a Japanese illustration of Gojong and the then-Queen Consort receiving Inoue Kaoru, the Japanese chargé d'affaires.[43] The illustration is marked 24 December 1894 and signed by the artist Ishizuka (石塚) with a legend "The [Korean] King and Queen, moved by our honest advice, realize the need for resolute reform for the first time." Lee said that the depiction of the clothes and background are very detailed and suggests that it was drawn at the scene as it happened. Both the King and Inoue were looking at the then-Queen Consort as though the conversation were taking place between the Queen and Inoue with the King listening.

In popular culture

Film and television

- Portrayed by Moon Geun-young, Lee Mi-yeon and Choi Myung-gil in the 2001-2002 KBS2 TV series Empress Myeongseong.

- Portrayed by Soo Ae in the 2009 film The Sword With No Name.[44]

- Portrayed by Seo Yi-sook in the 2010 SBS TV series Jejungwon.

- Portrayed by Ha Ji-eun in the 2014 KBS2 TV series Gunman in Joseon.

- Mentioned in tv series Miseuteo Shunshain Mr Sunshine in the English version. 2018 Season 1 episode 4 about 42:19 minutes into the episode. [1]

Musicals

- The Last Empress (musical)

See also

- Empress Myeongseong (TV drama)

The Last Empress (Musical)- List of Korea-related topics

- History of Korea

- Joseon Dynasty

- Heungseon Daewongun

- Emperor Gojong of the Korean Empire

- Korea royal refuge at the Russian legation

- Afanasy Ivanovich Seredin-Sabatin

Queen Inhyeon – Myeongseong's ascendant through his father (Min Chi-rok).

References

^ Park, Jong-hyo (박종효) (1 January 2002). "일본인 폭도가 가슴을 세 번 짓밟고 일본도로 난자했다" [Japanese mob tramped down her breast three times and violently stabbed her with a katana]. Sindonga 新東亞. pp. 472–485..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Korean Women in Resistance to the Japanese". Archived from the original on 2002-03-08.

^ S.C.M. Paine, The Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 316.

^ abc 아관파천 (in Korean). Naver/Doosan Encyclopedia.

^ Some sources say that she was born 25 September; the date discrepancy is due to the difference in the calendar systems. "Queen Min". Archived from the original on 2006-02-17.

^ The house she was born in was built in 1687, in the 13th year of King Sukjong, and was rebuilt in 1975 and 1976. In 1904, a stone monument inscribed with the handwriting of her husband Gojong (called the Tangangguribi) was erected on the alleged site used by her for study. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2007.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ The house is that in which she lived from her birth until she was eight. In 1687, a hut for the emperor's father-in-law, the father of Queen Inhyeon, Min Yu-jung was built. Only the main building remains today, but the building was restored to its natural state in 1995. In the room where the empress studied as a child, a monument was erected inscribed with the words "Empress Myeongseong Tangangguri" (the village where Empress Myeongseong was born) to commemorate her birth. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2008.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ The inscription, measuring 250 by 64 by 45 cm3, which her husband Gojong erected in 1904 (The Gwangmu Emperor's 8th year (Gapjin), 5th month, 1st day), read 明成皇后誕降舊里碑 명성황후탄강구리비 Myeongseong Hwanghu Tangangguribi The Stone Tablet for The Empress Myeongseong's Birthplace, her Former Village. http://www.minc.kr/rhmin/queen/myungsung/11_tomb.htm#tangang

^ abcdefgh Queen Min of Korea: Coming to Power "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 February 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-19.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ The Daewongun's wife is the Princess Consort to the Prince of the Great Court.

^ Based on the existing (lunar) calendar of the time. See "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 February 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-19.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Styled as "Her Majesty, the Central Hall" (jungjeon mama, 중전마마, 中殿媽媽).

^ History Resources Queen Min Archived 17 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

^ Szczepanski, Kallie, "Queen Min of Joseon Korea". http://asianhistory.about.com/od/southkorea/p/Queen-Min-of-Korea.htm

^ ab Neff, Robert (30 May 2010). "Korea's modernization through English in the 1880s". The Korea Times. Seoul, Korea: The Korea Times Co. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

^ 이화학당 梨花學堂 [Ewha Hankdang (Ewha Academy)] (in Korean). Nate/ Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011.1887년 학생이 7명으로 늘어났을 때, 명성황후는 스크랜튼 부인의 노고(勞苦)를 알고 친히 ‘이화학당(梨花學堂)’이라는 교명을 지어주고 외무독판(外務督辦) 김윤식(金允植)을 통해 편액(扁額)을 보내와 그 앞날을 격려했다. 당초에 스크랜튼 부인은 교명(校名)을 전신학교(專信學校, Entire Trust School)라 지으려 했으나, 명성황후의 은총에 화답하는 마음으로 ‘이화’로 택하였다.이는 당시에 황실을 상징하는 꽃이 순결한 배꽃〔梨花〕이었는데, 여성의 순결성과 명랑성을 상징하는 이름이었기때문이다.

^ The hospital was renamed "Jejungwon" on 23 April 1885. Currently, this would be the future Yonsei University & Severance Hospital.

^ The former Lilias Horton, wife of Horace Grant Underwood, (1851–1921).

^ Underwood, Lillias Horton (1904). Fifteen Years Among the Top-knots: Or, Life in Korea. pp. 24, 89–90.

^ abcd (in Korean) 을미사변 乙未事變 (in Korean) Naver Encyclopedia

^ ab ko:우범선

^ Peter Duus, The Abacus and the Sword: The Japanese Penetration of Korea, 1895–1910 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), p. 111.

^ Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and his World, 1852–1912 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), p. 517.

^ "Account Describes Empress Myongsong's Assassination". The Korea Times. 12 May 2005.

^ Aleksey Seredin-Sabatin (1895). "Testimony of the Russian citizen Seredin-Sabatin, in the service of the Korean court, who was on duty the night of 26 September". Columbia University. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 2013-03-24.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "Descendants of Korean Queen's Assassins Apologize". The Chosun Ilbo. 9 May 2005. Archived from the original on 21 June 2006.

^ Han Young-woo (한영우) (20 October 2001). Empress Myeongseong and Korean Empire (명성황후와 대한제국) (in Korean). Hyohyeong Publishing (효형출판). ISBN 89-86361-57-4.

^ ab Peter Duus, The Abacus and the Sword, p.76

^ ab Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan, p.520

^ Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan, p.59

^ Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan, p.515

^ Peter Duus, The Abacus and the Sword, p.111

^ Kenneth B. Pyle (1969). The New Generation in Meiji Japan: Problems of Cultural Identity, 1885–1895. Stanford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 0804706972.

^ abcd Kim Gi-cheol; Yu Seok-jae (9 May 2005). 명성황후 시해범 110년만의 사죄 (in Korean). The Chosun Ilbo.

^ Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and his World, 1852–1912 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), p. 516.

^ Han Young-woo, Empress Myeongseon and Korean Empire, p 47~50

^ ab Joseph Cummins. History's Great Untold Stories.

^ Franklin, Rausch (1 December 2013). "The Harbin An Jung-Geun Statue: A Korea/China-Japan Historical Memory Controversy". The Asia-Pacific Journal. 11 (48).

^ "Assassin's Grandson Speaks of Emotional Journey". The Chosun Ilbo. 10 May 2005. Archived from the original on 14 March 2009.

^ Korean Legal.org, http://www.koreaexpertwitness.com/blog/Korea,%20Don%20Southerton%20expert%20witness,%20Don%20Southerton%20Korea%20expert,%20Korea%20consulting,%20Korea%20consultant/empress-myeongseong/

^ "Photo of the Last Empress". KBS News. 28 December 2003.

^ "Japanese Illustration of Last Korean Queen Discovered". The Chosun Ilbo. 13 January 2005. Archived from the original on 21 June 2006.

^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1465518/synopsis

Further reading

Bird, Isabella. (1898). Korea and her Neighbours. London: Murray. OCLC 501671063. Reprinted 1987:

ISBN 9780804814898; OCLC 15109843

- Dechler, Martina. (1999). Culture and the State in Late Choson Korea.

ISBN 0-674-00774-3

- Duus, Peter. (1998). The Abacus and the Sword: The Japanese Penetration of Korea, 1895–1910. Berkeley: University of California Press.

ISBN 9780520086142/

ISBN 9780520213616;

OCLC 232346524

- Han, Young-woo, Empress Myeongseong and Korean Empire (명성황후와 대한제국)(2001). Hyohyeong Publishing

ISBN 89-86361-57-4

- Hann, Woo-Keun. (1996). The History of Korea.

ISBN 0-8248-0334-5

Keene, Donald. (2002). Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852–1912. New York: Columbia University Press.

ISBN 9780231123402; OCLC 46731178

- Lewis, James Bryant. (2003). Frontier Contact between Choson Korea and Tokugawa Japan.

ISBN 0-7007-1301-8

- MacKensie, Frederick Arthur. (1920). Korea's Fight for Freedom. Chicago: Fleming H. Revell. OCLC 3124752 Revised 2006:

ISBN 1-4280-1207-9 (See also Project Gutenberg.) - __________. (1908). The Tragedy of Korea. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 2008452 Reprinted 2006:

ISBN 1-901903-09-5

- Nahm, Andrew C. (1996). A History of the Korean People: Tradition and Transformation. (1996)

ISBN 0-930878-56-6

- _________. (1997). Introduction to Korean History and Culture.

ISBN 0-930878-08-6

- Schmid, Andre. (2002). Korea between Empires, 1895–1919. New York: Columbia University Press.

ISBN 9780231125383;

ISBN 9780231125390; OCLC 48618117

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Empress Myeongseong. |

Making of an Asian hit: A Korean royal tragedy in the Broadway style by Ricardo Saludo, Asia Week (18 December 1998)

Characteristics of Queen of Corea, The New York Times, 10 November 1895.

Japanese Document Sheds New Light on Korean Queen's Murder by Yoo Seok-jae, The Chosun Ilbo (12 January 2005)

Empress Myeongseong OST on YouTube