Battle of Cynoscephalae

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (April 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- For the earlier battle fought here, see Battle of Cynoscephalae (364 BC).

| Battle of Cynoscephalae | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Macedonian War | |||||||

A map showing the location of Cynoscephalae | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Aetolian League allies | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

22,000 infantry, 8,000 light infantry, 2,500 cavalry, and 20 war elephants 32,500 men total[1] | 16,000 phalangites, 2,000 light infantry, 5,500 mercenaries and allies, and 2,000 cavalry, 25,500 total [1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

about 700 killed and 2,000 wounded | 8,000 killed, 5,000 captured | ||||||

The Battle of Cynoscephalae (Greek: Μάχη τῶν Κυνὸς Κεφαλῶν) was an encounter battle fought in Thessaly in 197 BC between the Roman army, led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, and the Antigonid dynasty of Macedon, led by Philip V.

Contents

1 Prelude

2 Armies

2.1 Romans

2.2 Macedonians

3 Battle

4 Aftermath

5 Summary of the Battle of Cynoscephalae

6 Literature

7 External links

8 Notes

Prelude

In 201 BC, Rome won the Second Punic War against Carthage. Philip V of Macedon had attacked Rome's client states in the Mediterranean for 20 years. The Greek city-states, led by Athens, appealed to Rome for help. In 197 BC the Roman army of Titus Quinctius Flamininus, with his allies from the Aetolian League, marched out towards Pherae in search of Philip, who was at Larissa.

Armies

Romans

Flamininus had about 25,500 men, thus subdivided: 20,000 legionary infantry, 2,000 light infantry, 2,500 cavalry and 20 war elephants; further it included soldiers from the allied Aetolian League, light infantry from Athamania, and mercenary archers from Crete.

Macedonians

Philip had about 27,000 men of which 16,000 were phalangites, 4,000 light infantry, 5,000 mercenaries and allies from Crete, Illyria, Thrace, plus 2,000 cavalry. The Thessalian cavalry was led by Heracleides of Gyrton, the Macedonian cavalry by Leon. The mercenaries (except the Thracians) were commanded by Athenagoras and the second infantry corps by Nicanor the Elephant.

Battle

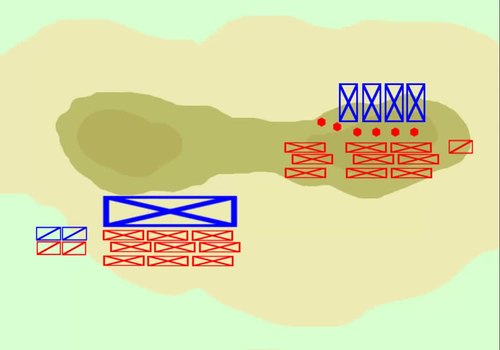

A tactical map of the battle showing the various phases

During the march there was a heavy rainstorm, and the morning after there was a fog over the hills and fields separating both camps. Despite this, Philip resumed his march, and his troops became confused and disoriented due to heavy fog. Philip then sent a small force to take the Cynoscephalae Hills (39°25′N 22°34′E / 39.417°N 22.567°E / 39.417; 22.567Coordinates: 39°25′N 22°34′E / 39.417°N 22.567°E / 39.417; 22.567). Flamininus, still unaware of Philip's location, sent out some cavalry and light infantry to reconnoiter, which engaged Philip's troops on the hills. The battle on the hills grew fierce and Flamininus sent 500 cavalry and 2,000 infantry as reinforcements, mostly Aetolians, forcing Philip's men to withdraw further up the hill. Philip now sent more men into the melee, his Macedonian and Thessalian cavalry, who drove the Romans down the hill, until the Aetolian cavalry stabilized the situation. Philip, though reluctant to send his phalanx into the broken, hilly terrain eventually ordered an assault with half the phalanx, 8,000 men when he heard of the Roman retreat. Flamininus positioned his troops on the field as well. He left his right wing in reserve, with his elephants in front, and personally led the left wing against Philip. Meanwhile, Philip's phalanx had reached the summit, and after joining with their light troops and cavalry which he placed on his right wing, Philip had his phalanx charge down the hill into the oncoming legionaries. As the Roman left was slowly being driven back, Flamininus took command of his right and ordered an assault there.

Philip's right wing was now on higher ground than the Roman left, and was at first successful against them. The phalanx drove the Romans down the slope. The Roman legions on the left did not break, and fought fiercely. However his left wing and center, commanded by Nicanor, never managed to form up properly. The Roman right attacked the Macedonians and were more successful than the Roman left. Flamininus concentrated his attack on Nicanor and the Macedonian left. Now that the battle was balanced, Flamininus sent his elephants charging into the phalangites, and they panicked. After breaking through, one of the Roman tribunes took twenty maniples (a smaller division of the legion) and attacked the Macedonian center and left from behind and the sides. The 20 Roman maniples numbered about 2,000 men. The Macedonians were unable to reposition themselves as quickly as the Roman maniples. The Macedonians raised their sarissas as a symbol of surrender. Either the Romans did not understand this signal, or they just ignored it. There was complete panic in the Macedonian ranks. Now surrounded by both wings of the Roman legion, they suffered heavy casualties and fled.

Aftermath

After a brief pursuit, Flamininus allowed Philip to escape. According to Polybius and Livy, 8,000 Macedonians had been killed. Livy mentions that other sources claim 32,000 Macedonians were killed and even one writer who due to "boundless exaggeration" claims 40,000 but concludes that Polybius is the trustworthy source on this matter.[2] Flamininus also took 5,000 prisoners. The Romans lost about 2,000 men and many more wounded.

It is generally perceived that with the later Battle of Pydna, this defeat demonstrated the superiority of the Roman legion over the Macedonian phalanx. The phalanx, though very powerful head on, was not as flexible as the Roman manipular formation and thus unable to adapt to changing conditions on the battlefield or break away from an engagement if necessary. This assertion has been challenged by some who point out that the Romans were only able to attain victory by taking advantage of the fact that the Macedonian left wing was not fully formed, although this is also given as evidence of the phalanx's unwieldy nature when compared to the legion. In any case, the result of the battle of Cynoscephalae was a fatal blow to the political aspirations of the Macedonian kingdom; Macedonia would never again be in a position to challenge Rome's geopolitical expansion. Although the peace that followed allowed Philip to keep his kingdom intact, Flamininus proclaimed that other Greek states previously under Macedonian domination were now free. Philip also had to pay 1,000 talents of silver to Rome, disband his navy, most of his army, and send his son to Rome as a hostage.

Summary of the Battle of Cynoscephalae

Play media

Play mediaAnimation of the battle. Click to play.

- There was a chance encounter between the advance groups of both armies at the summit near the pass. They approached from opposite sides.

- The right half of the Macedonian phalanx was formed in double depth and they advanced downhill against the Roman left wing.

- Flamininus saw his only hope was attacking the Macedonian left. He had the elephants followed by his right wing go uphill against the enemy's left wing.

- The Macedonian left wing had arrived on the summit. They were still in column formation and thrown into disorder. They were easily routed and pursued. If matters had concluded right there, the result would have been indecisive with the loss of a wing on each side.

- The Roman victory was achieved through the initiative of a tribune, whose name is unknown. He abandoned his part and attacked the rear of the Macedonian right wing, taking twenty maniples.

- This was the first time Roman legions were victorious over a Macedonian phalanx.

Literature

- N.G.L. Hammond, "The Campaign and Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC" in Journal of Hellenic Studies, 108 (1988)

- Polybius, Histories, XVIII. 19–27.

External links

- Livius.org: Cynoscephalae

Notes

^ ab Plutarch (100). "The Life of Titus Flamininus". The Parallel Lives. Loeb Classical Library..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Titus Livius (1905). "33.10 The Second Macedonian War – Continued". The History of Rome. 5. J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., London.