Confucius

Confucius 孔子 | |

|---|---|

The teaching Confucius. Portrait by Wu Daozi, 685–758, Tang dynasty. | |

| Born | 551 BC Zou, Lu, Zhou Kingdom (present-day Nanxinzhen, Qufu, Shandong, China) |

| Died | 479 BC (aged 71–72) Lu, Zhou Kingdom |

| Nationality | Zhou |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Chinese philosophy |

| School | Confucianism |

Main interests | Moral philosophy, social philosophy, ethics |

Notable ideas | Confucianism, Golden Rule |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

| Confucius | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Confucius (Kǒngzǐ)" in seal script (top) and regular (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 孔子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Kǒngzǐ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Master Kǒng" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kong Qiu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 孔丘 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Kǒng Qiū | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Khổng Tử | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 孔子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 공자 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 孔子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 孔子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | こうし | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Confucius (/kənˈfjuːʃəs/ kən-FEW-shəs;[1] 551–479 BC)[2][3] was a Chinese teacher, editor, politician, and philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period of Chinese history.

The philosophy of Confucius, also known as Confucianism, emphasized personal and governmental morality, correctness of social relationships, justice and sincerity. His followers competed successfully with many other schools during the Hundred Schools of Thought era only to be suppressed in favor of the Legalists during the Qin dynasty. Following the victory of Han over Chu after the collapse of Qin, Confucius's thoughts received official sanction and were further developed into a system known in the West as Neo-Confucianism, and later New Confucianism (Modern Neo-Confucianism).

Confucius is traditionally credited with having authored or edited many of the Chinese classic texts including all of the Five Classics, but modern scholars are cautious of attributing specific assertions to Confucius himself. Aphorisms concerning his teachings were compiled in the Analects, but only many years after his death.

Confucius's principles have commonality with Chinese tradition and belief. He championed strong family loyalty, ancestor veneration, and respect of elders by their children and of husbands by their wives, recommending family as a basis for ideal government. He espoused the well-known principle "Do not do unto others what you do not want done to yourself", the Golden Rule. He is also a traditional deity in Daoism.

Confucius is widely considered as one of the most important and influential individuals in shaping human history. His teaching and philosophy greatly impacted people around the world and remains influential today.[4][5]

Contents

1 Name

2 Life

2.1 Early life

2.2 Political career

2.3 Exile

2.4 Return home

3 Philosophy

3.1 Ethics

3.2 Politics

4 Legacy

4.1 Disciples

4.2 Visual portraits

4.3 Memorials

4.4 Descendants

5 References

5.1 Citations

5.2 Bibliography

6 External links

Name

The name "Confucius" is a Latinized form of the Mandarin Chinese "Kǒng Fūzǐ" (孔夫子, meaning "Master Kǒng"), and was coined in the late 16th century by the early Jesuit missionaries to China.[6] Confucius's clan name was "Kǒng" (孔; Old Chinese: *[k]ʰˤoŋʔ), and his given name was "Qiū" (丘; OC: *[k]ʷʰə). His "capping name", given upon reaching adulthood and by which he would have been known to all but his older family members, was "Zhòngní" (仲尼, OC:*N-truŋ-s nr[əj]), the "Zhòng" indicating that he was the second son in his family.[6][7]

Life

Early life

Lu can be seen in China's northeast.

It is thought that Confucius was born on September 28, 551 BC,[2][8] in the district of Zou (鄒邑) near present-day Qufu, China.[8][9] The area was notionally controlled by the kings of Zhou but effectively independent under the local lords of Lu. His father Kong He (or Shuliang He) was an elderly commandant of the local Lu garrison.[10]His ancestry traced back through the dukes of Song to the Shang dynasty which had preceded the Zhou.[11][12][13][14] Traditional accounts of Confucius's life relate that Kong He's grandfather had migrated the family from Song to Lu.[15]

Kong He died when Confucius was three years old, and Confucius was raised by his mother Yan Zhengzai (顏徵在) in poverty.[16] His mother would later die at less than 40 years of age.[16] At age 19 he married Qiguan (亓官), and a year later the couple had their first child, Kong Li (孔鯉).[16] Qiguan and Confucius would later have two daughters together, one of whom is thought to have died as a child.[17]

Confucius was educated at schools for commoners, where he studied and learned the Six Arts.[18]

Confucius was born into the class of shi (士), between the aristocracy and the common people. He is said to have worked in various government jobs during his early 20s, and as a bookkeeper and a caretaker of sheep and horses, using the proceeds to give his mother a proper burial.[16][19] When his mother died, Confucius (aged 23) is said to have mourned for three years, as was the tradition.[19]

Political career

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

In Confucius's time, the state of Lu was headed by a ruling ducal house.[20] Under the duke were three aristocratic families, whose heads bore the title of viscount and held hereditary positions in the Lu bureaucracy. The Ji family held the position "Minister over the Masses", who was also the "Prime Minister"; the Meng family held the position "Minister of Works"; and the Shu family held the position "Minister of War". In the winter of 505 BC, Yang Hu—a retainer of the Ji family—rose up in rebellion and seized power from the Ji family. However, by the summer of 501 BC, the three hereditary families had succeeded in expelling Yang Hu from Lu.[21] By then, Confucius had built up a considerable reputation through his teachings, while the families came to see the value of proper conduct and righteousness, so they could achieve loyalty to a legitimate government. Thus, that year (501 BC), Confucius came to be appointed to the minor position of governor of a town. Eventually, he rose to the position of Minister of Crime.[22]

Confucius desired to return the authority of the state to the duke by dismantling the fortifications of the city—strongholds belonging to the three families. This way, he could establish a centralized government. However, Confucius relied solely on diplomacy as he had no military authority himself. In 500 BC, Hou Fan—the governor of Hou—revolted against his lord of the Shu family. Although the Meng and Shu families unsuccessfully besieged Hou, a loyalist official rose up with the people of Hou and forced Hou Fan to flee to the Qi state. The situation may have been in favor for Confucius as this likely made it possible for Confucius and his disciples to convince the aristocratic families to dismantle the fortifications of their cities. Eventually, after a year and a half, Confucius and his disciples succeeded in convincing the Shu family to raze the walls of Hou, the Ji family in razing the walls of Bi, and the Meng family in razing the walls of Cheng. First, the Shu family led an army towards their city Hou and tore down its walls in 498 BC.[23]

Soon thereafter, Gongshan Furao or Buniu, a retainer of the Ji family, revolted and took control of the forces at Bi.[24][25] He immediately launched an attack and entered the capital Lu.[23] Earlier, Gongshan had approached Confucius to join him, which Confucius considered. Even though he disapproved the use of a violent revolution, the Ji family dominated the Lu state force for generations and had exiled the previous duke. Although he wanted the opportunity to put his principles into practice, Confucius gave up on this idea in the end.[24] Creel (1949) states that, unlike the rebel Yang Hu before him, Gongshan may have sought to destroy the three hereditary families and restore the power of the duke.[26] However, Dubs (1946) is of the view that Gongshan was encouraged by Viscount Ji Huan to invade the Lu capital in an attempt to avoid dismantling the Bi fortified walls.[25] Whatever the situation may have been, Gongshan was considered an upright man who continued to defend the state of Lu, even after he was forced to flee.[26][27]

During the revolt by Gongshan, Zhong You had managed to keep the duke and the three viscounts together at the court.[27] Zhong You was one of the disciples of Confucius and Confucius had arranged for him to be given the position of governor by the Ji family.[28] When Confucius heard of the raid, he requested that Viscount Ji Huan allow the duke and his court to retreat to a stronghold on his palace grounds.[29] Thereafter, the heads of the three families and the duke retreated to the Ji's palace complex and ascended the Wuzi Terrace. Confucius ordered two officers to lead an assault against the rebels.[30] At least one of the two officers was a retainer of the Ji family, but they were unable to refuse the orders while in the presence of the duke, viscounts, and court.[29] The rebels were pursued and defeated at Gu. Immediately after the revolt was defeated, the Ji family razed the Bi city walls to the ground.[30]

The attackers retreated after realizing that they would have to become rebels against the state and their lord. Through Confucius's actions, the Bi officials had inadvertently revolted against their own lord, thus forcing Viscount Ji Huan's hand in having to dismantle the walls of Bi (as it could have harbored such rebels) or confess to instigating the event by going against proper conduct and righteousness as an official. Dubs (1949) suggests that the incident brought to light Confucius's foresight, practical political ability, and insight into human character.[29]

When it was time to dismantle the city walls of the Meng family, the governor was reluctant to have his city walls torn down and convinced the head of the Meng family not to do so.[30] The Zuozhuan recalls that the governor advised against razing the walls to the ground as he said that it made Cheng vulnerable to the Qi state and cause the destruction of the Meng family.[29] Even though Viscount Meng Yi gave his word not to interfere with an attempt, he went back on his earlier promise to dismantle the walls.[29]

Later in 498 BC, Duke Ding personally went with an army to lay siege to Cheng in an attempt to raze its walls to the ground, but he did not succeed.[31] Thus, Confucius could not achieve the idealistic reforms that he wanted including restoration of the legitimate rule of the duke.[32] He had made powerful enemies within the state, especially with Viscount Ji Huan, due to his successes so far.[33] According to accounts in the Zuozhuan and Shiji, Confucius departed his homeland in 497 BC after his support for the failed attempt of dismantling the fortified city walls of the powerful Ji, Meng, and Shu families.[34] He left the state of Lu without resigning, remaining in self-exile and unable to return as long as Viscount Ji Huan was alive.[33]

Exile

Map showing the journey of Confucius to various states between 497 BC and 484 BC.

The Shiji stated that the neighboring Qi state was worried that Lu was becoming too powerful while Confucius was involved in the government of the Lu state. According to this account, Qi decided to sabotage Lu's reforms by sending 100 good horses and 80 beautiful dancing girls to the duke of Lu. The duke indulged himself in pleasure and did not attend to official duties for three days. Confucius was disappointed and resolved to leave Lu and seek better opportunities, yet to leave at once would expose the misbehavior of the duke and therefore bring public humiliation to the ruler Confucius was serving. Confucius therefore waited for the duke to make a lesser mistake. Soon after, the duke neglected to send to Confucius a portion of the sacrificial meat that was his due according to custom, and Confucius seized upon this pretext to leave both his post and the Lu state.

After Confucius's resignation, he began a long journey or set of journeys around the principality states of north-east and central China including Wey, Song, Zheng, Cao, Chu, Qi, Chen, and Cai (and a failed attempt to go to Jin). At the courts of these states, he expounded his political beliefs but did not see them implemented.

Return home

Tomb of Confucius in Kong Lin cemetery, Qufu, Shandong Province

According to the Zuozhuan, Confucius returned home to his native Lu when he was 68, after he was invited to do so by Ji Kangzi, the chief minister of Lu.[35] The Analects depict him spending his last years teaching 72 or 77 disciples and transmitting the old wisdom via a set of texts called the Five Classics.

During his return, Confucius sometimes acted as an advisor to several government officials in Lu, including Ji Kangzi, on matters including governance and crime.[35]

Burdened by the loss of both his son and his favorite disciples, he died at the age of 71 or 72. He died from natural causes. Confucius was buried in Kong Lin cemetery which lies in the historical part of Qufu in the Shandong Province.[citation needed] The original tomb erected there in memory of Confucius on the bank of the Sishui River had the shape of an axe. In addition, it has a raised brick platform at the front of the memorial for offerings such as sandalwood incense and fruit.

Philosophy

The Dacheng Hall, the main hall of the Temple of Confucius in Qufu

Although Confucianism is often followed in a religious manner by the Chinese, many argue that its values are secular and that it is, therefore, less a religion than a secular morality. Proponents argue, however, that despite the secular nature of Confucianism's teachings, it is based on a worldview that is religious.[36] Confucianism discusses elements of the afterlife and views concerning Heaven, but it is relatively unconcerned with some spiritual matters often considered essential to religious thought, such as the nature of souls. However, Confucius is said to have believed in astrology, saying: "Heaven sends down its good or evil symbols and wise men act accordingly".[37]

The Analects of Confucius

In the Analects, Confucius presents himself as a "transmitter who invented nothing". He puts the greatest emphasis on the importance of study, and it is the Chinese character for study (學) that opens the text. Far from trying to build a systematic or formalist theory, he wanted his disciples to master and internalize older classics, so that their deep thought and thorough study would allow them to relate the moral problems of the present to past political events (as recorded in the Annals) or the past expressions of commoners' feelings and noblemen's reflections (as in the poems of the Book of Odes).

Ethics

One of the deepest teachings of Confucius may have been the superiority of personal exemplification over explicit rules of behavior. His moral teachings emphasized self-cultivation, emulation of moral exemplars, and the attainment of skilled judgment rather than knowledge of rules. Confucian ethics may, therefore, be considered a type of virtue ethics. His teachings rarely rely on reasoned argument, and ethical ideals and methods are conveyed indirectly, through allusion, innuendo, and even tautology. His teachings require examination and context to be understood. A good example is found in this famous anecdote:

- 廄焚。子退朝,曰:“傷人乎?” 不問馬。

When the stables were burnt down, on returning from court Confucius said, "Was anyone hurt?" He did not ask about the horses.

Analects X.11 (tr. Waley), 10–13 (tr. Legge), or X-17 (tr. Lau)

By not asking about the horses, Confucius demonstrates that the sage values human beings over property; readers are led to reflect on whether their response would follow Confucius's and to pursue self-improvement if it would not have. Confucius serves not as an all-powerful deity or a universally true set of abstract principles, but rather the ultimate model for others. For these reasons, according to many commentators, Confucius's teachings may be considered a Chinese example of humanism.

One of his teachings was a variant of the Golden Rule, sometimes called the "Silver Rule" owing to its negative form:

- 己所不欲,勿施於人。

- "What you do not wish for yourself, do not do to others."

- 子貢問曰:“有一言而可以終身行之者乎?”子曰:“其恕乎!己所不欲、勿施於人。”

Zi Gong [a disciple] asked: "Is there any one word that could guide a person throughout life?"

The Master replied: "How about 'reciprocity'! Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself."

Analects XV.24, tr. David Hinton

Often overlooked in Confucian ethics are the virtues to the self: sincerity and the cultivation of knowledge. Virtuous action towards others begins with virtuous and sincere thought, which begins with knowledge. A virtuous disposition without knowledge is susceptible to corruption, and virtuous action without sincerity is not true righteousness. Cultivating knowledge and sincerity is also important for one's own sake; the superior person loves learning for the sake of learning and righteousness for the sake of righteousness.

The Confucian theory of ethics as exemplified in lǐ (禮) is based on three important conceptual aspects of life: (a) ceremonies associated with sacrifice to ancestors and deities of various types, (b) social and political institutions, and (c) the etiquette of daily behavior. It was believed by some that lǐ originated from the heavens, but Confucius stressed the development of lǐ through the actions of sage leaders in human history. His discussions of lǐ seem to redefine the term to refer to all actions committed by a person to build the ideal society, rather than those simply conforming with canonical standards of ceremony.

In the early Confucian tradition, lǐ was doing the proper thing at the proper time, balancing between maintaining existing norms to perpetuate an ethical social fabric, and violating them in order to accomplish ethical good. Training in the lǐ of past sages cultivates in people virtues that include ethical judgment about when lǐ must be adapted in light of situational contexts.

In Confucianism, the concept of li is closely related to yì (義), which is based upon the idea of reciprocity. Yì can be translated as righteousness, though it may simply mean what is ethically best to do in a certain context. The term contrasts with action done out of self-interest. While pursuing one's own self-interest is not necessarily bad, one would be a better, more righteous person if one's life was based upon following a path designed to enhance the greater good. Thus an outcome of yì is doing the right thing for the right reason.

Just as action according to lǐ should be adapted to conform to the aspiration of adhering to yì, so yì is linked to the core value of rén (仁).Rén consists of 5 basic virtues: seriousness, generosity, sincerity, diligence and kindness.[38]Rén is the virtue of perfectly fulfilling one's responsibilities toward others, most often translated as "benevolence" or "humaneness"; translator Arthur Waley calls it "Goodness" (with a capital G), and other translations that have been put forth include "authoritativeness" and "selflessness." Confucius's moral system was based upon empathy and understanding others, rather than divinely ordained rules. To develop one's spontaneous responses of rén so that these could guide action intuitively was even better than living by the rules of yì. Confucius asserts that virtue is a mean between extremes. For example, the properly generous person gives the right amount—not too much and not too little.[38]

Politics

Confucius's political thought is based upon his ethical thought. He argued that the best government is one that rules through "rites" (lǐ) and people's natural morality, and not by using bribery and coercion. He explained that this is one of the most important analects: "If the people be led by laws, and uniformity sought to be given them by punishments, they will try to avoid the punishment, but have no sense of shame. If they be led by virtue, and uniformity sought to be given them by the rules of propriety, they will have the sense of the shame, and moreover will become good." (Translated by James Legge) in the Great Learning (大學). This "sense of shame" is an internalisation of duty, where the punishment precedes the evil action, instead of following it in the form of laws as in Legalism.

Confucius looked nostalgically upon earlier days, and urged the Chinese, particularly those with political power, to model themselves on earlier examples. In times of division, chaos, and endless wars between feudal states, he wanted to restore the Mandate of Heaven (天命) that could unify the "world" (天下, "all under Heaven") and bestow peace and prosperity on the people. Because his vision of personal and social perfections was framed as a revival of the ordered society of earlier times, Confucius is often considered a great proponent of conservatism, but a closer look at what he proposes often shows that he used (and perhaps twisted) past institutions and rites to push a new political agenda of his own: a revival of a unified royal state, whose rulers would succeed to power on the basis of their moral merits instead of lineage. These would be rulers devoted to their people, striving for personal and social perfection, and such a ruler would spread his own virtues to the people instead of imposing proper behavior with laws and rules.

Confucius did not believe in the concept of "democracy", which is itself an Athenian concept unknown in ancient China, but could be interpreted by Confucius's principles recommending against individuals electing their own political leaders to govern them, or that anyone is capable of self-government. He expressed fears that the masses lacked the intellect to make decisions for themselves, and that, in his view, since not everyone is created equal, not everyone has a right of self-government.[39]

While he supported the idea of government ruling by a virtuous king, his ideas contained a number of elements to limit the power of rulers. He argued for representing truth in language, and honesty was of paramount importance. Even in facial expression, truth must always be represented. Confucius believed that if a ruler is to lead correctly, by action, that orders would be unnecessary in that others will follow the proper actions of their ruler. In discussing the relationship between a king and his subject (or a father and his son), he underlined the need to give due respect to superiors. This demanded that the subordinates must advise their superiors if the superiors are considered to be taking a course of action that is wrong. Confucius believed in ruling by example, if you lead correctly, orders by force or punishment are not necessary.[40]

Legacy

Confucius's teachings were later turned into an elaborate set of rules and practices by his numerous disciples and followers, who organized his teachings into the Analects.[41][42] Confucius's disciples and his only grandson, Zisi, continued his philosophical school after his death.[43] These efforts spread Confucian ideals to students who then became officials in many of the royal courts in China, thereby giving Confucianism the first wide-scale test of its dogma.

Two of Confucius's most famous later followers emphasized radically different aspects of his teachings. In the centuries after his death, Mencius (孟子) and Xun Zi (荀子) both composed important teachings elaborating in different ways on the fundamental ideas associated with Confucius. Mencius (4th century BC) articulated the innate goodness in human beings as a source of the ethical intuitions that guide people towards rén, yì, and lǐ, while Xun Zi (3rd century BC) underscored the realistic and materialistic aspects of Confucian thought, stressing that morality was inculcated in society through tradition and in individuals through training. In time, their writings, together with the Analects and other core texts came to constitute the philosophical corpus of Confucianism.

This realignment in Confucian thought was parallel to the development of Legalism, which saw filial piety as self-interest and not a useful tool for a ruler to create an effective state. A disagreement between these two political philosophies came to a head in 223 BC when the Qin state conquered all of China. Li Si, Prime Minister of the Qin dynasty, convinced Qin Shi Huang to abandon the Confucians' recommendation of awarding fiefs akin to the Zhou Dynasty before them which he saw as being against to the Legalist idea of centralizing the state around the ruler. When the Confucian advisers pressed their point, Li Si had many Confucian scholars killed and their books burned—considered a huge blow to the philosophy and Chinese scholarship.

Under the succeeding Han and Tang dynasties, Confucian ideas gained even more widespread prominence. Under Wudi, the works of Confucius were made the official imperial philosophy and required reading for civil service examinations in 140 BC which was continued nearly unbroken until the end of the 19th century. As Mohism lost support by the time of the Han, the main philosophical contenders were Legalism, which Confucian thought somewhat absorbed, the teachings of Laozi, whose focus on more spiritual ideas kept it from direct conflict with Confucianism, and the new Buddhist religion, which gained acceptance during the Southern and Northern Dynasties era. Both Confucian ideas and Confucian-trained officials were relied upon in the Ming Dynasty and even the Yuan Dynasty, although Kublai Khan distrusted handing over provincial control to them.

During the Song dynasty, the scholar Zhu Xi (AD 1130–1200) added ideas from Daoism and Buddhism into Confucianism. In his life, Zhu Xi was largely ignored, but not long after his death, his ideas became the new orthodox view of what Confucian texts actually meant. Modern historians view Zhu Xi as having created something rather different and call his way of thinking Neo-Confucianism. Neo-Confucianism held sway in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam until the 19th century.

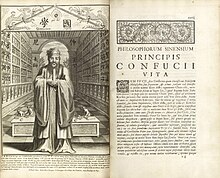

Confucius, Philosopher of the Chinese, published by Jesuit missionaries at Paris in 1687.

The works of Confucius were first translated into European languages by Jesuit missionaries in the 16th century during the late Ming dynasty. The first known effort was by Michele Ruggieri, who returned to Italy in 1588 and carried on his translations while residing in Salerno. Matteo Ricci started to report on the thoughts of Confucius, and a team of Jesuits—Prospero Intorcetta, Philippe Couplet, and two others—published a translation of several Confucian works and an overview of Chinese history in Paris in 1687.[44][45]François Noël, after failing to persuade Clement XI that Chinese veneration of ancestors and Confucius did not constitute idolatry, completed the Confucian canon at Prague in 1711, with more scholarly treatments of the other works and the first translation of the collected works of Mencius.[46] It is thought that such works had considerable importance on European thinkers of the period, particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Western civilization.[45][47]

In the modern era Confucian movements, such as New Confucianism, still exist, but during the Cultural Revolution, Confucianism was frequently attacked by leading figures in the Communist Party of China. This was partially a continuation of the condemnations of Confucianism by intellectuals and activists in the early 20th century as a cause of the ethnocentric close-mindedness and refusal of the Qing Dynasty to modernize that led to the tragedies that befell China in the 19th century.

Confucius's works are studied by scholars in many other Asian countries, particularly those in the Chinese cultural sphere, such as Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Many of those countries still hold the traditional memorial ceremony every year.

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community believes Confucius was a Divine Prophet of God, as were Lao-Tzu and other eminent Chinese personages.[48]

In modern times, Asteroid 7853, "Confucius", was named after the Chinese thinker.[49]

Disciples

Zengzi (right) kneeling before Confucius (center), as depicted in a painting from the Illustrations of the Classic of Filial Piety, Song dynasty

Confucius began teaching after he turned 30, and taught more than 3,000 students in his life, about 70 of whom were considered outstanding. His disciples and the early Confucian community they formed became the most influential intellectual force in the Warring States period.[50] The Han dynasty historian Sima Qian dedicated a chapter in his Records of the Grand Historian to the biographies of Confucius's disciples, accounting for the influence they exerted in their time and afterward. Sima Qian recorded the names of 77 disciples in his collective biography, while Kongzi Jiayu, another early source, records 76, not completely overlapping. The two sources together yield the names of 96 disciples.[51] 22 of them are mentioned in the Analects, while the Mencius records 24.[52]

Confucius did not charge any tuition, and only requested a symbolic gift of a bundle of dried meat from any prospective student. According to his disciple Zigong, his master treated students like doctors treated patients and did not turn anybody away.[51] Most of them came from Lu, Confucius's home state, with 43 recorded, but he accepted students from all over China, with six from the state of Wey (such as Zigong), three from Qin, two each from Chen and Qi, and one each from Cai, Chu, and Song.[51] Confucius considered his students' personal background irrelevant, and accepted noblemen, commoners, and even former criminals such as Yan Zhuoju and Gongye Chang.[53] His disciples from richer families would pay a sum commensurate with their wealth which was considered a ritual donation.[51]

Confucius's favorite disciple was Yan Hui, most probably one of the most impoverished of them all.[52] Sima Niu, in contrast to Yan Hui, was from a hereditary noble family hailing from the Song state.[52] Under Confucius's teachings, the disciples became well-learned in the principles and methods of government.[54] He often engaged in discussion and debate with his students and gave high importance to their studies in history, poetry, and ritual.[54] Confucius advocated loyalty to principle rather than to individual acumen, in which reform was to be achieved by persuasion rather than violence.[54] Even though Confucius denounced them for their practices, the aristocracy was likely attracted to the idea of having trustworthy officials who were studied in morals as the circumstances of the time made it desirable.[54] In fact, the disciple Zilu even died defending his ruler in Wey.[54]

Yang Hu, who was a subordinate of the Ji family, had dominated the Lu government from 505 to 502 and even attempted a coup, which narrowly failed.[54] As a likely consequence, it was after that that the first disciples of Confucius were appointed to government positions.[54] A few of Confucius's disciples went on to attain official positions of some importance, some of which were arranged by Confucius.[55] By the time Confucius was 50 years old, the Ji family had consolidated their power in the Lu state over the ruling ducal house.[56] Even though the Ji family had practices with which Confucius disagreed and disapproved, they nonetheless gave Confucius's disciples many opportunities for employment.[56] Confucius continued to remind his disciples to stay true to their principles and renounced those who did not, all the while being openly critical of the Ji family.[57]

Visual portraits

No contemporary painting or sculpture of Confucius survives, and it was only during the Han Dynasty that he was portrayed visually. Carvings often depict his legendary meeting with Laozi. Since that time there have been many portraits of Confucius as the ideal philosopher. The oldest known portrait of Confucius has been unearthed in the tomb of the Han dynasty ruler Marquis of Haihun (died 59 BC). The picture was painted on the wooden frame to a polished bronze mirror.[58]

In former times, it was customary to have a portrait in Confucius Temples; however, during the reign of Hongwu Emperor (Taizu) of the Ming dynasty, it was decided that the only proper portrait of Confucius should be in the temple in his home town, Qufu in Shandong. In other temples, Confucius is represented by a memorial tablet. In 2006, the China Confucius Foundation commissioned a standard portrait of Confucius based on the Tang dynasty portrait by Wu Daozi.

Memorials

First entrance gate of the Temple of Confucius in Zhenhai

Soon after Confucius's death, Qufu, his home town, became a place of devotion and remembrance. The Han dynasty Records of the Grand Historian records that it had already become a place of pilgrimage for ministers. It is still a major destination for cultural tourism, and many people visit his grave and the surrounding temples. In Sinic cultures, there are many temples where representations of the Buddha, Laozi, and Confucius are found together. There are also many temples dedicated to him, which have been used for Confucian ceremonies.

Followers of Confucianism have a tradition of holding spectacular memorial ceremonies of Confucius (祭孔) every year, using ceremonies that supposedly derived from Zhou Li (周禮) as recorded by Confucius, on the date of Confucius's birth. In the twentieth century, this tradition was interrupted for several decades in mainland China, where the official stance of the Communist Party and the State was that Confucius and Confucianism represented reactionary feudalist beliefs which held that the subservience of the people to the aristocracy is a part of the natural order. All such ceremonies and rites were therefore banned. Only after the 1990s did the ceremony resume. As it is now considered a veneration of Chinese history and tradition, even Communist Party members may be found in attendance.

In Taiwan, where the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) strongly promoted Confucian beliefs in ethics and behavior, the tradition of the memorial ceremony of Confucius (祭孔) is supported by the government and has continued without interruption. While not a national holiday, it does appear on all printed calendars, much as Father's Day or Christmas Day do in the Western world.

In South Korea, a grand-scale memorial ceremony called Seokjeon Daeje is held twice a year on Confucius's birthday and the anniversary of his death, at Confucian academies across the country and Sungkyunkwan in Seoul.

Descendants

Confucius's descendants were repeatedly identified and honored by successive imperial governments with titles of nobility and official posts. They were honored with the rank of a marquis thirty-five times since Gaozu of the Han dynasty, and they were promoted to the rank of duke forty-two times from the Tang dynasty to the Qing dynasty. Emperor Xuanzong of Tang first bestowed the title of "Duke Wenxuan" on Kong Suizhi of the 35th generation. In 1055, Emperor Renzong of Song first bestowed the title of "Duke Yansheng" on Kong Zongyuan of the 46th generation.

During the Southern Song dynasty, the Duke Yansheng Kong Duanyou fled south with the Song Emperor to Quzhou in Zhejiang, while the newly established Jin dynasty (1115–1234) in the north appointed Kong Duanyou's brother Kong Duancao who remained in Qufu as Duke Yansheng.[59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68] From that time up until the Yuan dynasty, there were two Duke Yanshengs, one in the north in Qufu and the other in the south at Quzhou. An invitation to come back to Qufu was extended to the southern Duke Yansheng Kong Zhu by the Yuan-dynasty Emperor Kublai Khan. The title was taken away from the southern branch after Kong Zhu rejected the invitation,[69] so the northern branch of the family kept the title of Duke Yansheng. The southern branch remained in Quzhou where they live to this day. Confucius's descendants in Quzhou alone number 30,000.[70][71] The Hanlin Academy rank of Wujing boshi 五經博士 was awarded to the southern branch at Quzhou by a Ming Emperor while the northern branch at Qufu held the title Duke Yansheng.[72][73] The leader of the southern branch is 孔祥楷 Kong Xiangkai.[74]

In 1351, during the reign of Emperor Toghon Temür of the Yuan dynasty, 93rd-generation descendant Kong Huan (孔浣)'s 2nd son Kong Shao (孔昭) moved from China to Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty, and was received courteously by Princess Noguk (the Mongolian-born wife of the future king Gongmin). After being naturalized as a Korean citizen, he changed the hanja of his name from "昭" to "紹" (both pronounced so in Korean),[75] married a Korean woman and bore a son (Gong Yeo (Hangul: 공여; Hanja: 孔帤), 1329–1397), therefore establishing the Changwon Gong clan (Hangul: 창원 공씨; Hanja: 昌原 孔氏), whose ancestral seat was located in Changwon, South Gyeongsang Province.

The clan then received an aristocratic rank during the succeeding Joseon Dynasty.[76][77][78][79][80] In 1794, during the reign of King Jeongjo, the clan then changed its name to Gokbu Gong clan (Hangul: 곡부 공씨; Hanja: 曲阜 孔氏) in honor of Confucius's birthplace Qufu (Hangul: 곡부; Hanja: 曲阜; RR: Gokbu), Shandong Province.[81]

Famous descendants include actors such as Gong Yoo (real name Gong Ji-cheol (공지철)) & Gong Hyo-jin (공효진); and artists such as male idol group B1A4 member Gongchan (real name Gong Chan-sik (공찬식)), singer-songwriter Minzy (real name Gong Min-ji (공민지)), as well as her great-aunt traditional folk dancer Gong Ok-jin (공옥진).

Despite repeated dynastic change in China, the title of Duke Yansheng was bestowed upon successive generations of descendants until it was abolished by the Nationalist Government in 1935. The last holder of the title, Kung Te-cheng of the 77th generation, was appointed Sacrificial Official to Confucius. Kung Te-cheng died in October 2008, and his son, Kung Wei-yi, the 78th lineal descendant, had died in 1989. Kung Te-cheng's grandson, Kung Tsui-chang, the 79th lineal descendant, was born in 1975; his great-grandson, Kung Yu-jen, the 80th lineal descendant, was born in Taipei on January 1, 2006. Te-cheng's sister, Kong Demao, lives in mainland China and has written a book about her experiences growing up at the family estate in Qufu. Another sister, Kong Deqi, died as a young woman.[82] Many descendants of Confucius still live in Qufu today.

A descendant of Confucius, H. H. Kung was the Premier of the Republic of China. One of his sons, Kong Lingjie 孔令傑 married Debra Paget[83] who gave birth to Gregory Kung (孔德基).

Confucius's family, the Kongs, have the longest recorded extant pedigree in the world today. The father-to-son family tree, now in its 83rd generation,[84] has been recorded since the death of Confucius. According to the Confucius Genealogy Compilation Committee, he has 2 million known and registered descendants, and there are an estimated 3 million in all.[85] Of these, several tens of thousands live outside of China.[85] In the 14th century, a Kong descendant went to Korea, where an estimated 34,000 descendants of Confucius live today.[85] One of the main lineages fled from the Kong ancestral home in Qufu during the Chinese Civil War in the 1940s and eventually settled in Taiwan.[82] There are also branches of the Kong family who have converted to Islam after marrying Muslim women, in Dachuan in Gansu province in the 1800s,[86] and in 1715 in Xuanwei city in Yunnan province.[87] Many of the Muslim Confucius descendants are descended from the marriage of Ma Jiaga (马甲尕), a Muslim woman, and Kong Yanrong (孔彦嵘), 59th generation descendant of Confucius in the year 1480 and are found among the Hui and Dongxiang peoples.[88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96] The new genealogy includes the Muslims.[97] Kong Dejun (孔德軍) is a prominent Islamic scholar and Arabist from Qinghai province and a 77th generation descendant of Confucius.

Because of the huge interest in the Confucius family tree, there was a project in China to test the DNA of known family members of the collateral branches in mainland China.[98] Among other things, this would allow scientists to identify a common Y chromosome in male descendants of Confucius. If the descent were truly unbroken, father-to-son, since Confucius's lifetime, the males in the family would all have the same Y chromosome as their direct male ancestor, with slight mutations due to the passage of time.[99] The aim of the genetic test was the help members of collateral branches in China who lost their genealogical records to prove their descent. However, in 2009, many of the collateral branches decided not to agree to DNA testing.[100]Bryan Sykes, professor of genetics at Oxford University, understands this decision: "The Confucius family tree has an enormous cultural significance," he said. "It's not just a scientific question."[100] The DNA testing was originally proposed to add new members, many of whose family record books were lost during 20th-century upheavals, to the Confucian family tree.[101] The main branch of the family which fled to Taiwan was never involved in the proposed DNA test at all.

In 2013 a DNA test performed on multiple different families who claimed descent from Confucius found that they shared the same Y chromosome as reported by Fudan University.[102]

The fifth and most recent edition of the Confucius genealogy was printed by the Confucius Genealogy Compilation Committee (CGCC).[103][104] It was unveiled in a ceremony at Qufu on September 24, 2009.[103][104] Women are now included for the first time.[105]

References

Citations

^ "Confucius". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Hugan, Yong (2013). Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed. A&C Black. p. 3. ISBN 978-1441196538. Archived from the original on 2017-04-16.

^ Riegel 2012, online.

^ "The Life and Significance of Confucius". www.sjsu.edu.

^ "China Confucianism: Life of Confucius, Influences, Development". www.travelchinaguide.com.

^ ab Nivison (1999), p. 752.

^ Wilkinson (2015), p. 133.

^ ab Creel 1949, 25.

^ Rainey 2010, 16.

^ Legge (1887), p. 260.

^ Legge (1887), p. 259.

^ Yao 1997, 29.

^ Yao 2000, 23.

^ Rainey 2010, 66.

^ Creel 1949, 26.

^ abcd Huang, Yong (2013). Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed. A&C Black. p. 4. ISBN 978-1441196538. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

^ Schuman, Michael (2015). Confucius: And the World He Created. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465040575. Archived from the original on 2017-04-16.

^ Huang, Yong (2013). Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed. A&C Black. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9781441196538. Archived from the original on 2017-04-16.

^ ab Burgan, Michael (2008). Confucius: Chinese Philosopher and Teacher. Capstone. p. 23. ISBN 9780756538323. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

^ Dubs 1946, 274–275.

^ Dubs 1946, 275.

^ Dubs 1946, 275–276.

^ ab Dubs 1946, 277.

^ ab Creel 1949, 35–36.

^ ab Dubs 1946, 277–278.

^ ab Creel 1949, 35.

^ ab Dubs 1946, 278.

^ Dubs 1946, 278–279.

^ abcde Dubs 1946, 279.

^ abc Chin 2007, 30.

^ Dubs 1946, 280.

^ Dubs 1946, 280–281.

^ ab Dubs 1946, 281.

^ Riegel 1986, 13.

^ ab Huang, Yong (2013). Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed. A&C Black. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-1441196538. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

^ Berger, Peter (February 15, 2012). "Is Confucianism a Religion?". The American Interest. Archived from the original on August 17, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

^ Parkers (1983)

^ ab Bonevac & Phillips 2009, 40.

^ Schuman, Michael (2015). Confucius: And the World He Created. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465040575. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

^ Violatti, Cristian (August 31, 2013). "Confucianism". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

^ Knechtges & Shih (2010), p. 645.

^ Kim & Csikszentmihalyi (2010), p. 25.

^ Ames, Roger T. and David L. Hall (2001). Focusing the Familiar: A Translation and Philosophical Interpretation of the Zhongyong. University of Hawaii Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0824824600.

^ Intorcetta, Prospero; et al., eds. (1687), Confucius Sinarum Philosophus, sive, Scientia Sinensis Latine Exposita [Confucius, Philosopher of the Chinese, or, Chinese Knowledge Explained in Latin], Paris: Daniel Horthemels. (in Latin)

^ ab Parker 1977, 25.

^ Noël, François, ed. (1711), Sinensis Imperii Libri Classici Sex [The Six Classic Books of the Chinese Empire], Prague: Charles-Ferdinand University Press. (in Latin)

^ Hobson 2004, 194–195.

^ Ahmad n.d., online.

^ IAU Minor Planet Center. International Astronomical Union Minor Planet Center. Accessed 12 September 2018.

^ Shen (2013), p. 86.

^ abcd Shen (2013), p. 87.

^ abc Creel 1949, 30.

^ Shen (2013), p. 88.

^ abcdefg Creel 1949, 32.

^ Creel 1949, 31.

^ ab Creel 1949, 33.

^ Creel 1949, 32–33.

^ "Confucius depicted on mirror". The Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

^ "Descendants and Portraits of Confucius in the Early Southern Song" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-09-13. Retrieved 2016-05-03.

^ Banning, B. Paul. "AAS Abstracts: China Session 45". aas2.asian-studies.org. Archived from the original on 2016-10-06.

^ "AAS Abstracts: China Session 45: On Sacred Grounds: The Material Culture and Ritual Formation of the Confucian Temple in Late Imperial China". Association for Asian Studies. Archived from the original on 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

^ "The Ritual Formation of Confucian Orthodoxy and the Descendants of the Sage (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate.

^ Wilson, Thomas A. "Cult of Confucius". academics.hamilton.edu.

^ "- Quzhou City Guides – China TEFL Network". en.chinatefl.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

^ "confucianism". kfz.freehostingguru.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-13.

^ "Nation observes Confucius anniversary". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-01-08.

^ "Confucius Anniversary Celebrated". www.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 2015-09-14.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-06-10. Retrieved 2016-05-03.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Thomas Jansen; Thoralf Klein; Christian Meyer (2014). Globalization and the Making of Religious Modernity in China: Transnational Religions, Local Agents, and the Study of Religion, 1800–Present. Brill. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-9004271517.

^ "Nation observes Confucius anniversary". China Daily. 2006-09-29. Archived from the original on 2016-01-08.

^ "Confucius Anniversary Celebrated". China Daily. September 29, 2006. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015.

^ Thomas A. Wilson (2002). On Sacred Grounds: Culture, Society, Politics, and the Formation of the Cult of Confucius. Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 69, 315. ISBN 978-0674009615.

^ Thomas Jansen; Thoralf Klein; Christian Meyer (2014). Globalization and the Making of Religious Modernity in China: Transnational Religions, Local Agents, and the Study of Religion, 1800–Present. Brill. pp. 188–. ISBN 978-9004271517.

^ Thomas Jansen; Thoralf Klein; Christian Meyer (2014). Globalization and the Making of Religious Modernity in China: Transnational Religions, Local Agents, and the Study of Religion, 1800–Present. Brill. pp. 189–. ISBN 978-9004271517. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017.

^ Due to a naming taboo regarding the birth name of the 4th king of Goryeo Gwangjong, born "Wang So" (Hangul: 왕소; Hanja: 王昭).

^ "Descendants of Confucius in South Korea Seek Roots in Quzhou". Quzhou.China. 2014-05-19. Archived from the original on 2015-02-04. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

^ english@peopledaily.com.cn. "South Korea home to 80,000 descendants of Confucius – People's Daily Online". en.people.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-08-28.

^ "New Confucius Genealogy out next year". www.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-10-10.

^ "China Exclusive: Korean Confucius descendants trace back to ancestor of family tree". www.china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-06-01.

^ "China Exclusive: Korean Confucius descendants trace back to ancestor of family tree". www.news.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 2016-07-29.

^ Doosan Encyclopedia 공 孔. Doosan Encyclopedia.

^ ab Kong, Ke & Roberts 1988.[page needed]

^ Bacon, James (April 21, 1962). "Debra Paget Weds Oilman, Nephew of Madame Chiang". Independent. p. 11. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved June 11, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

^ China Economic Net 2009, online.

^ abc Yan 2008, online.

^ Jing, Jun (1998). The Temple of Memories: History, Power, and Morality in a Chinese Village. Stanford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0804764926. Archived from the original on 2015-10-17.

^ Zhou, Jing. "New Confucius Genealogy out next year". china.org.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-10-10. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

^ 3139. "孔子后裔中有14个少数民族 有宗教信仰也传承家风 – 文化 – 人民网". culture.people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19.

^ chinanews. "孔子后裔中有14个少数民族 有宗教信仰也传承家风–中新网". www.chinanews.com. Archived from the original on 2016-08-28.

^ 李典典. "孔子後裔有14個少數民族 外籍後裔首次入家譜_台灣網". big5.taiwan.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-10-06.

^ L_103782. "孔子后裔中有14个少数民族 有宗教信仰也传承家风 – 山东频道 – 人民网". sd.people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-08-28.

^ "西北生活着孔子回族后裔 – 文化 – 人民网". culture.people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-04-09.

^ 350. "孔子后裔有回族 – 地方 – 人民网". unn.people.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-08-28.

^ "孔子后裔有回族? – 宁夏百科". ningxia.baike.com. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19.

^ "孔子后裔有回族? – 回族百科". huizu.baike.com.

^ "孔子后裔有回族" [Confucius descendants have Hui nationality]. Archived from the original on 2016-04-13. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

^ rmhb.com.cn ([permanent dead link])

^ Ministry of Commerce of the PRC 2006, online.

^ "DNA Testing Adopted to Identify Confucius Descendants". China Internet Information Center. 19 June 2006.

^ ab Qiu 2008, online.

^ Bandao 2007, online.

^ Chen, Stephen (13 November 2013). "Study finds single bloodline among self-claimed Confucius descendants". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015.

^ ab China Daily 2009, online.

^ ab Zhou 2008, online.

^ China Daily 2007, online.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Ahmad, Mirza Tahir (n.d.). "Confucianism". Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

Bonevac, Daniel; Phillips, Stephen (2009). Introduction to world philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195152319.

Creel, Herrlee Glessner (1949). Confucius: The man and the myth. New York: John Day Company.

Dubs, Homer H. (1946). "The political career of Confucius". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 66 (4): 273–282. JSTOR 596405.

Hobson, John M. (2004). The Eastern origins of Western civilisation (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521547246.

Chin, Ann-ping (2007). The Authentic Confucius: A Life of Thought and Politics. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0743246187.

"Confucius Descendants Say DNA Testing Plan Lacks Wisdom". Bandao. 21 August 2007. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011.

"Confucius Family Tree to Record Female Kin". China Daily. 2 February 2007.

"Confucius' Family Tree Recorded Biggest". China Daily. 24 September 2009.

"Confucius family tree revision ends with 2 mln descendants". China Economic Net. 4 January 2009.

Kim, Tae Hyun; Csikszentmihalyi, Mark (2010). "Chapter 2". In Olberding, Amy. Dao Companion to the Analects. Springer. pp. 21–36. ISBN 9400771126.

Knechtges, David R.; Shih, Hsiang-ling (2010). "Lunyu 論語". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping. Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part One. Leiden: Brill. pp. 645–50. ISBN 978-9004191273.

Kong, Demao; Ke, Lan; Roberts, Rosemary (1988). The house of Confucius (Translated ed.). London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0340412794.

Legge, James (1887), "Confucius", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th ed., Vol. VI, pp. 258–265.

"DNA test to clear up Confucius confusion". Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China. 18 June 2006.

Nivison, David Shepherd (1999). "The Classical Philosophical Writings – Confucius". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward. The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 752–59. ISBN 978-0521470308.

Parker, John (1977). Windows into China: The Jesuits and their books, 1580–1730. Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston. ISBN 978-0890730508.

Phan, Peter C. (2012). "Catholicism and Confucianism: An intercultural and interreligious dialogue". Catholicism and interreligious dialogue. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199827879.

Rainey, Lee Dian (2010). Confucius & Confucianism: The essentials. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405188418.

Riegel, Jeffrey K. (1986). "Poetry and the legend of Confucius's exile". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 106 (1): 13–22. JSTOR 602359.

Riegel, Jeffrey (2012). "Confucius". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University.

Qiu, Jane (13 August 2008). "Inheriting Confucius". Seed Magazine.

Shen, Vincent (2013). Dao Companion to Classical Confucian Philosophy. Springer. ISBN 978-9048129362.

Wilkinson, Endymion (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual (4th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0674088467.

Yan, Liang (16 February 2008). "Updated Confucius family tree has two million members". Xinhua.

Yao, Xinzhong (1997). Confucianism and Christianity: A Comparative Study of Jen and Agape. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1898723769.

Yao, Xinzhong (2000). An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521644303.

Zhou, Jing (31 October 2008). "New Confucius Genealogy out next year". China Internet Information Center.

- Further reading

Clements, Jonathan (2008). Confucius: A Biography. Stroud, Gloucestershire, England: Sutton Publishing.

ISBN 978-0750947756.- Confucius (1997). Lun yu, (in English The Analects of Confucius). Translation and notes by Simon Leys. New York: W.W. Norton.

ISBN 0393040194. - Confucius (2003). Confucius: Analects – With Selections from Traditional Commentaries. Translated by E. Slingerland. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. (Original work published c. 551–479 BC)

ISBN 0872206351.

Creel, Herrlee Glessner (1949). Confucius and the Chinese Way. New York: Harper.

Creel, Herrlee Glessner (1953). Chinese Thought from Confucius to Mao Tse-tung. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2005). "Confucianism: An Overview". In Encyclopedia of Religion (Vol. C, pp. 1890–1905). Detroit: MacMillan Reference

Dawson, Raymond (1982). Confucius. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192875365.

Fingarette, Hebert (1998). Confucius : the secular as sacred. Long Grove, Ill.: Waveland Press. ISBN 978-1577660101.

Nylan, Michael and Thomas A. Wilson (2010). Lives of Confucius: Civilization's Greatest Sage through the Ages. ISBN 978-0385510691.

Ssu-ma Ch'ien (1974). Records of the Historian. Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang, trans. Hong Kong: Commercial Press.

- Van Norden, B.W., ed. (2001). Confucius and the Analects: New Essays. New York: Oxford University Press.

ISBN 019513396X. - Van Norden, B.W., trans. (2006). Mengzi, in Philip J. Ivanhoe & B.W. Van Norden, Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy. 2nd ed. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

ISBN 0872207803.

External links

"Confucius". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Confucius on In Our Time at the BBC

- Multilingual web site on Confucius and the Analects

The Dao of Kongzi, introduction to the thought of Confucius.

Riegel, Jeffrey. "Confucius". In Zalta, Edward N. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Works by Confucius at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about Confucius at Internet Archive

Works by Confucius at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Confucian Analects (Project Gutenberg release of James Legge's Translation)

Core philosophical passages in the Analects of Confucius.