Piccadilly Gardens

Piccadilly Gardens

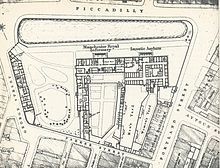

Aerial view of Piccadilly Gardens

Piccadilly Gardens is a green space in Manchester city centre, England, between Market Street and the edge of the Northern Quarter. Piccadilly runs eastwards from the junction of Market Street with Mosley Street to the junction of London Road with Ducie Street; to the south are the gardens and paved areas. The area was reconfigured in 2002 with a water feature and concrete pavilion by Japanese architect Tadao Ando.

Contents

1 History

2 Criticism

3 Transport

4 Buildings and statues

4.1 Piccadilly Plaza

4.2 Thistle and Britannia Hotels

4.3 Wheel of Manchester

4.4 Listed buildings around Piccadilly Gardens

5 Sources

6 References

7 External links

History

- Before 1755: The area was occupied by water-filled clay pits called the Daub Holes. The Lord of the Manor donated the site and the pits were replaced by a fine ornamental pond.[1]

- 1755: Manchester Royal Infirmary was built here; the street it stood on was then called Lever's Row, which continued south-east as Piccadilly.[2]

- 1763: Manchester Royal Lunatic Asylum was built next to the Manchester Royal Infirmary.

- 1849: The lunatic asylum was moved to Cheadle and is now Cheadle Royal Hospital.

- 1910: The Manchester Royal Infirmary moved to its current site on Oxford Road in 1908. The hospital buildings were completely demolished by April 1910 apart from the outpatient department, which continued to deal with minor injuries and dispense medication until the 1930s.[3]

- 1914: After several years in which the Manchester Corporation tried to decide how to develop the site, it was left and made into the largest open green space in the city centre. The Manchester Public Free Library Reference Department was housed on the site for a number of years before the move to Manchester Central Library. The sunken garden was a remnant of the hospital's basement.

- 2001–2003: Redevelopment of the gardens and the construction of One Piccadilly Gardens office building.

The square at Piccadilly Gardens has been for many years the central hub of Manchester's public transport system. The square is only five minutes' walk from the mainline Manchester Piccadilly railway station and 10 minutes walk from Manchester Victoria railway station.

As part of the ongoing regeneration of the city centre, the city council had set up an international competition for the redesign of Piccadilly Gardens. The winners – announced in 1998 from a short-list that had been whittled down to six – were the landscape architects EDAW and its partners, consisting of: the engineers Arup; renowned Japanese architect Tadao Ando; local architects Chapman Robinson; and lighting engineer, Peter Fink.[4] The square was finally revamped in 2001–02, to include new green space and fountains (by EDAW), and a pavilion (by Tadao Ando) which partially functions to shield the gardens from the transport interchange. At the same time One Piccadilly Gardens was constructed on the eastern edge of the square. The resulting space was radically different from the old gardens, and the only links to the past that remained were the original statues. The redesign was part of the massive construction process that covered Manchester in the buildup to the city hosting the 2002 Commonwealth Games. Previously the square was becoming increasingly run down and was considered unsafe.[5] At a contract cost of around £10 million Piccadilly Gardens was renovated and ended up being shortlisted in 2003 for the Better Public Building Award. Part of the area was built on to help fund the redevelopment.

Criticism

The redevelopment of the Gardens soon came under fire for its "cold, modernistic" design.[6] The concrete partition wall was dubbed the "Berlin Wall" by locals, and the hastily turfed grass regularly turned to mud after some public use. It continues to be returfed regularly.[7] The fountains, whilst popular with children in the summer, have also been subject to scrutiny, with broken glass regularly an issue. One Piccadilly Gardens is also controversial, not only for the sale of public land to private enterprise, but also because it dominates the skyline in the area, and blocks sunlight from the south-east.[citation needed]

Transport

Piccadilly Gardens has a major public transport interchange where buses and trams can be boarded:

- There are two Metrolink tram stops in the immediate vicinity. Piccadilly Gardens is south of the "gardens" area and serves all trams to and from Piccadilly railway station, while Market Street is on Market Street to the north and serves all trams to and from Victoria railway station.

- Next to the Piccadilly Gardens stop there is also a bus station, Manchester Piccadilly bus station, and many more bus stops in the nearby streets.

Information on Manchester's transport system can be requested at the Transport for Greater Manchester "Travelshop", located next to the bus station and tram stop.[citation needed]

Buildings and statues

City Tower, Piccadilly Plaza

Mercure Piccadilly Hotel, Piccadilly Plaza

Queen Victoria statue

The square is surrounded by buildings that cover the ages of modern Manchester. From old Victorian warehouses and shops dating from the Industrial Revolution and Manchester's role as the cotton marketing capital to the new office block development which is part of the 21st century regeneration of the square. The building that visitors are likely to notice first is the huge complex of Piccadilly Plaza which stands over Piccadilly.

One Piccadilly Gardens, built in 2003, lies on the eastern edge of the square and houses offices on six floors, with shops and restaurants on the ground floor. It lies between Piccadilly and the square itself.

Piccadilly Plaza

Piccadilly Plaza was originally built by Covell Matthews and Partners from 1959 to 1965 and has been recently re-modelled by Leslie Jones Architects in 2001 (this mainly involved replacing the old Chinese style-roofed towers of Bernard House).[8] Piccadilly Plaza contains the renovated Mercure Hotel (formerly known as the Ramada Manchester Piccadilly and Jarvis Piccadilly Hotel); the refurbishment was completed in 2008. The huge tower block, originally known as Sunley Tower, was renamed City Tower. In 2005 the Plaza underwent large-scale remodelling with recladding of the tower and cleaning of concrete façades. The whole complex has benefited from increased investment from Bruntwood Ltd, which bought Piccadilly Plaza in 2004–05, and now several retail outlets on ground level, and large office space on the levels above (once the home of Piccadilly Radio) are available.

Thistle and Britannia Hotels

The Thistle Hotel stands on the south-eastern side of Piccadilly Gardens. The hotel was originally three cotton warehouses (with a fourth standing to the left) which made up the four warehouses designed by Edward Walters between 1851 and 1858. Also, there is the Grade II* listed Britannia Hotel[9] on Portland Street which was formerly the largest of Manchester warehouses: Watts Warehouse (architects Travis & Mangnall).

Wheel of Manchester

From 2013 to 2015, the Wheel of Manchester was based in the square.[10][11]

Listed buildings around Piccadilly Gardens

1. Grade II listed on 3 October 1974.

12 Mosley Street. (Barclays Bank) Grade II Listed on 20 June 1988. Architect Thomas Worthington (1826–1909) born in Salford. Thomas Worthington was the architect for the Albert Memorial (for Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha) which stands in front of the Manchester Town Hall in Albert Square.

15 & 17. (including Nos 1–3 Oldham Street). Grade II listed on 20 June 1988. Architect Royle & Bennett.

38–50. Joshua Hoyle Building & Roby House. Grade II listed on 17 July 1987. Now converted into the Malmaison Hotel.

47. Grade II listed on 6 June 1994.

49. Grade II listed on 6 June 1994.

51 & 53. Grade II listed on 6 June 1994.

59 & 61, Clayton House. Grade II listed on 6 June 1994.

69–75. Hall's Buildings. Grade II listed on 20 June 1988.

77–83. Grade II listed on 20 June 1988.

97. Brunswick Hotel (includes 2 & 4 Paton Street). Grade II listed on 3 October 1974.

107. Grade II listed on 3 October 1974.

1. Tib Street, corner of Piccadilly, 1879. Grade II listed. Architect James Lynde.

In addition to the many listed buildings that stand around Piccadilly Gardens there are also numerous statues:

Sir Robert Peel statue, Grade II listed on 3 October 1974.

James Watt statue, Grade II listed on 3 October 1974.

Edward Onslow Ford's Queen Victoria Monument. Grade II listed on 3 October 1974.

Duke of Wellington statue. Grade II listed on 3 October 1974.

These four stand on what was the esplanade of the infirmary and were erected at different times before the move to Oxford Road. The first was Peel's statue in 1853 and the last Queen Victoria's which came after her death.[12]

Sources

- Kidd, Alan: "Manchester" – .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 978-0-7486-1551-3

References

^ Atkins, Philip (1976). Guide Across Manchester. Manchester: Civic Trust for the North West. ISBN 0-901347-29-9.

^ Aston, Joseph (1804) Plan of Manchester and Salford with the latest improvements. In: The Manchester Guide... Manchester: Joseph Aston

^ Brockbank, William (1952). Portrait of a Hospital. London: William Heinemann. p. 158.|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ "Piccadilly Gardens (design process)". Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE). Retrieved 2008-06-28.

^ "Manchester city centre regeneration (EDAW)". Resource for Urban Design Information (RUDI). Retrieved 2008-06-28.

^ "Piccadilly Gardens: Action At Last". Manchester Confidential. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

^ "'Dirty' and 'depressing': Piccadilly Gardens is Manchester's worst attraction". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

^ "Best of MCR...The Lost Buildings". Retrieved 19 April 2018.

^ Historic England. "Britannia Hotel (Grade II*) (1246952)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

^ "New Years Firework Spectacular at Piccadilly Gardens Manchester". Manchester Gazette. 29 December 2013. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014.

^ Jennifer Williams (9 June 2015). "Work to dismantle Piccadilly Gardens big wheel to begin tonight, say council bosses". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

^ Makepeace, Chris (1972) Manchester As It Was: [Vol. I] Victorian Street Scenes. Nelson, Lancs.: Hendon; pp. 28–30

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Piccadilly Gardens, Manchester. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Piccadilly – East Centre. |

- Piccadilly Gardens Manchester Archives+

- Manchester City Council's Regeneration Team

Coordinates: 53°28′51″N 2°14′13″W / 53.48093°N 2.23699°W / 53.48093; -2.23699