Klamath Falls, Oregon

Klamath Falls, Oregon | |

|---|---|

City | |

Downtown Klamath Falls | |

| Nickname(s): Oregon's City of Sunshine | |

| Motto(s): "Working For You" | |

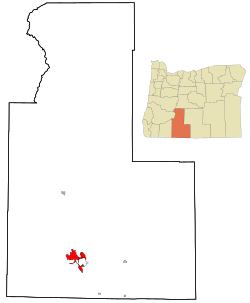

Location in Oregon | |

Klamath Falls Location in the United States Show map of Oregon  Klamath Falls Klamath Falls (the US) Show map of the US | |

| Coordinates: 42°13′30″N 121°46′54″W / 42.22500°N 121.78167°W / 42.22500; -121.78167Coordinates: 42°13′30″N 121°46′54″W / 42.22500°N 121.78167°W / 42.22500; -121.78167 | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Klamath |

| Incorporated | 1905 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Carol Westfall |

| Area [1] | |

| • Total | 53.51 km2 (20.66 sq mi) |

| • Land | 51.31 km2 (19.81 sq mi) |

| • Water | 2.20 km2 (0.85 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,249.4 m (4,099 ft) |

| Population (2010)[2] | |

| • Total | 20,840 |

| • Estimate (2013)[3] | 21,207 |

| • Density | 406.2/km2 (1,052.0/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (Pacific) |

| ZIP codes | 97601, 97603 |

| Area code(s) | 541 |

| FIPS code | 41-39700[4] |

GNIS feature ID | [5] |

| Website | City Website |

Klamath Falls (/ˈklæməθ/ KLAM-əth) (Klamath: ʔiWLaLLoonʔa[6]) is a city in and the county seat of Klamath County, Oregon, United States. The city was originally called Linkville when George Nurse founded the town in 1867. It was named after the Link River, on whose falls the city was sited. The name was changed to Klamath Falls in 1893.[7] The population was 20,840 at the 2010 census.[8] The city is on the southeastern shore of the Upper Klamath Lake and about 25 miles (40 km) north of the California–Oregon border.

The Klamath Falls area had been inhabited by Native Americans for at least 4,000 years before the first European settlers. The Klamath Basin became part of the Oregon Trail with the opening of the Applegate Trail. Logging was Klamath Falls's first major industry.

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Water rights controversy

2.2 Geothermal heating

2.3 Air quality

3 Geography

3.1 Climate

4 Demographics

4.1 2010 census

4.2 2000 census

5 Government and politics

6 Economy

7 Military airbase

8 Education

8.1 Colleges and universities

8.2 Public schools

9 Recreation

10 Transportation

11 Notable people

12 Sister city

13 Radio stations

14 See also

15 References

15.1 Sources

16 External links

Etymology

After its founding in 1867, Klamath Falls was originally named Linkville.[9] The name was changed to Klamath Falls in 1892–93.[10] The name Klamath /ˈklæməθ/,[11] may be a variation of the descriptive native for "people" [in Chinookan] used by the indigenous peoples of the Northwest Plateau to refer to the region.[12] Several locatives derived from the Modoc or Achomawi: lutuami, lit: "lake dwellers", móatakni, "tule lake dwellers", respectively, could have also led to spelling variations that ultimately made the word what it is today. No evidence suggests that the name is from Klamath origin. The Klamath themselves called the region Yulalona or Iwauna, which referred to the phenomenon of the Link River flowing upstream when the south wind blew hard.

The Klamath name for the Link River white water falls was Tiwishkeni, or "where the falling waters rush".[13] From this Link River white water phenomenon "Falls" was added to Klamath in its name. In reality it's best described as rapids rather than falls. The rapids are visible a short distance below the Link River Dam, where the water flow is generally insufficient to provide water flow over the river rocks.

History

The Klamath and Modoc Indians were the first known inhabitants of the area. The Modocs' homeland is about 20 miles (32 km) south of Klamath Falls, but when they were pushed onto a reservation with their adversaries, the Klamath, a rebellion ensued and they hid out in nearby lava beds.[14] This led to the Modoc War of 1872−1873, which was a hugely expensive campaign for the US Cavalry, costing an estimated $500,000 − the equivalent of over $8 million in year-2000 dollars. Seventeen Indians and 83 whites were killed.[15]

The Applegate Trail, which passes through the lower Klamath area, was blazed in 1846 from west to east in an attempt to provide a safer route for emigrants on the Oregon Trail.[16] The first non-Indian settler is considered to have been Wallace Baldwin, a 19-year-old civilian who drove fifty head of horses in the valley in 1852.[17] In 1867, George Nurse, named the small settlement "Linkville", because of Link River north of Lake Ewauna.

The Klamath Reclamation Project began in 1906 to drain marshland and move water to allow for agriculture. With the building of the main "A" Canal, water was first made available May 22, 1907. Veterans of World War I and World War II were given homesteading opportunities on the reclaimed land.[18]

During World War II, a Japanese-American internment camp, the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, was located in nearby Newell, California, and a satellite of the Camp White, Oregon, POW camp was located just on the Oregon-California border near the town of Tulelake, California. In May 1945, about 30 miles (48 km) east of Klamath Falls, (near Bly, Oregon) a Japanese Fu-Go balloon bomb killed a woman and five children on a church outing. This is said to be the only Japanese-inflicted casualty on the US mainland during the war.

Timber harvesting through the use of railroad was extensive in Klamath County for the first few decades of the 20th century.[19] With the arrival of the Southern Pacific Transportation Company in 1909, Klamath Falls grew quickly from a few hundred to several thousand. Dozens of lumber mills cut fir and pine lumber, and the industry flourished until the late 1980s when the northern spotted owl and other endangered species were driving forces in changing western forest policy.[citation needed]

On September 20, 1993, a series of earthquakes struck near Klamath Falls.[20]

Many downtown buildings, including the county courthouse and the former Sacred Heart Academy and Convent, were damaged or destroyed. There were two deaths attributed to the earthquake.

Water rights controversy

Link River downstream white water falls from which Klamath Falls got its name.

The city made national headlines in 2001 when a court decision was made to shut off Klamath Project irrigation water on April 6 because of Endangered Species Act requirements. The Lost River sucker and shortnose sucker were listed on the Federal Endangered Species List in 1988, and when drought struck in 2001, a panel of scientists stated that further diversion of water for agriculture would be detrimental to these species, which reside in the Upper Klamath Lake, as well as to the protected Coho salmon which spawn in the Klamath River. Many protests by farmers and citizens culminated in a "Bucket Brigade"[21] on Main Street May 7, 2001, in Klamath Falls. The event was attended by 18,000 farmers, ranchers, citizens, and politicians. Two giant bucket monuments have since been constructed and erected in town to commemorate the event. Such universal criticism resulted in a new plan implemented in early 2002 to resume irrigation to farmers.

Low river flows in the Klamath and Trinity rivers and high temperatures led to a mass die-off of at least 33,000 salmon in 2002.[22] Dwindling salmon numbers have practically shut down the fishing industry in the region and caused over $60 million in disaster aid being given to fishermen to offset losses.[23] Ninety percent of Trinity River water is diverted for California agriculture.[24]

According to a National Academy of Sciences report of October 22, 2003, limiting irrigation water did little if anything to help endangered fish and may have hurt the populations.[25] A contrary report has criticized the National Academy of Sciences report.[23] The Chiloquin Dam has been removed to help improve sucker spawning habitat.

Geothermal heating

Klamath Falls is located in a known geothermal resource area. Geothermal power has been used directly for geothermal heating in the area since the early 1900s.[26] A downtown district heating system was constructed in 1981 and extended in 1982. There was public opposition to the scheme. Many homes were heated by private geothermal wells, and owners were concerned that the city system could lower the water level and/or reduce water temperatures. System operation was delayed until 1984 following an aquifer study. Full operational testing showed no negative impact on the private wells. The system was shut down again in 1986 after multiple distribution piping failures were discovered. By 1991, the distribution piping had been reconstructed, and the system was again operating. The system has been expanded since then, and according to the Oregon Institute of Technology, the operation is "at or near operational break-even".[26] The system is used to provide direct heat for homes, city schools, greenhouses, government and commercial buildings, geothermally heated snowmelt systems for sidewalks and roads, and process heat for the wastewater treatment plant.[26]

Air quality

According to Oregon's Department of Environmental Quality significant efforts are being made to improve the air quality in the Klamath Basin. The following excerpts are from a report produced by DEQ in September 2012.

- Because of topography, weather and a large number of woodstoves, the Klamath Falls area has a long history of identifying problems with particulate pollutions and working to solve them. With increased understanding of the health effects of particulates, EPA has made the standards more protective over time, addressing smaller sized particles that are the most hazardous but more difficult to control. Since 1994, the Klamath Falls area has attained the larger or coarse (PM10) particulate matter standard. In 2009, with the adoption of a fine particulate (PM2.5) matter standard, EPA changed the legal status of the Klamath Falls Area from attainment (meeting air quality standards) to nonattainment (not meeting air quality standards) for fine particulate matter (PM2.5). DEQ has adopted an attainment plan with associated regulations to ensure that the Klamath Falls area meets the current PM2.5 standard."

- In November 2007, Klamath County revised its Clean Air Ordinance to implement early particulate reductions, including:

- Revising woodstove curtailment levels to restrict wood burning when weather conditions could lead to accumulation of particulate in the Klamath Falls area

- Requiring removal of an uncertified woodstove upon sale of a home

- Prohibiting the use of burn barrels

- Tightening enforcement of wood stove curtailment

- A series of woodstove change-out efforts funded by the city of Klamath Falls, EPA and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act resulted in replacement of 584 woodstoves and significant emission reductions between 2008 and 2011."[27]

- In November 2007, Klamath County revised its Clean Air Ordinance to implement early particulate reductions, including:

Geography

Upper Klamath Lake Canoe Trail, with ponderosa pine and quaking aspen in fall foliage

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 20.66 square miles (53.51 km2), of which 19.81 square miles (51.31 km2) is land and 0.85 square miles (2.20 km2) is water.[1] The elevation is 4,099 feet (1,249 m).

Klamath Falls has a high desert landscape. The older part of the city is located above natural geothermal springs. These have been used for the heating of homes and streets, primarily in the downtown area.[28]

Climate

Klamath Falls is known as "Oregon’s City of Sunshine" because the area enjoys 300 days of sun per year.[29] Klamath Falls is a high desert and features a climate with cold snowy winters along with hot summer afternoons and cool summer nights. Under the Köppen climate classification the city’s climate type is Csb, often described as Warm Summer Mediterranean. Using the 0 °C (32 °F) isotherm preferred by some climatologists Klamath Falls is a Dsb climate, often described as Warm Summer Continental Mediterranean.

Typical of its region, Klamath Falls has a dry season in summertime, with the greatest precipitation occurring in wintertime, much of it falling as snow. Although it is not arid or semi-arid, total precipitation is still low, at 13.41 inches (340.6 mm) per year, due to Klamath Falls being in the rain shadow of the Cascade Mountains to the west. The wettest "rain year" has been from July 1957 to June 1958 with 20.36 inches (517.1 mm) and the driest from July 1954 to June 1955 with 6.09 inches (154.7 mm).[30] The all-time record high is 105 °F (40.6 °C), set on July 27, 1911, and the all-time record low is −24 °F (−31.1 °C), set on January 15, 1888.[31] The freeze-free season averages around 120 days,[32] with the first freeze in a typical year being on September 21, and the last freeze being on June 1.[33][34] On average 21 days per year reach 90 °F (32.2 °C) or higher, and two nights per year reach temperatures of 0 °F (−17.8 °C) or lower.

| Climate data for Klamath Falls, Oregon | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) | 69 (21) | 77 (25) | 87 (31) | 98 (37) | 100 (38) | 105 (41) | 104 (40) | 103 (39) | 92 (33) | 79 (26) | 63 (17) | 105 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 38.1 (3.4) | 44.0 (6.7) | 50.8 (10.4) | 59.3 (15.2) | 67.5 (19.7) | 75.7 (24.3) | 85.3 (29.6) | 84.0 (28.9) | 76.0 (24.4) | 63.7 (17.6) | 48.3 (9.1) | 39.4 (4.1) | 61 (16.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 20.6 (−6.3) | 24.5 (−4.2) | 28.1 (−2.2) | 32.5 (0.3) | 39.0 (3.9) | 45.0 (7.2) | 51.4 (10.8) | 49.8 (9.9) | 43.2 (6.2) | 35.4 (1.9) | 28.2 (−2.1) | 22.7 (−5.2) | 35 (1.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −24 (−31) | −10 (−23) | −5 (−21) | 10 (−12) | 17 (−8) | 22 (−6) | 28 (−2) | 28 (−2) | 20 (−7) | 11 (−12) | 1 (−17) | −17 (−27) | −24 (−31) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.99 (50.5) | 1.39 (35.3) | 1.27 (32.3) | 0.81 (20.6) | 0.98 (24.9) | 0.77 (19.6) | 0.29 (7.4) | 0.40 (10.2) | 0.55 (14) | 1.03 (26.2) | 1.83 (46.5) | 2.10 (53.3) | 13.41 (340.8) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.1 (30.7) | 6.0 (15.2) | 3.8 (9.7) | 1.2 (3) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.3 (0.8) | 3.8 (9.7) | 9.1 (23.1) | 36.5 (92.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 81 |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center[35][36] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 250 | — | |

| 1890 | 364 | 45.6% | |

| 1900 | 447 | 22.8% | |

| 1910 | 2,758 | 517.0% | |

| 1920 | 4,801 | 74.1% | |

| 1930 | 16,093 | 235.2% | |

| 1940 | 16,497 | 2.5% | |

| 1950 | 15,875 | −3.8% | |

| 1960 | 16,949 | 6.8% | |

| 1970 | 15,775 | −6.9% | |

| 1980 | 16,661 | 5.6% | |

| 1990 | 17,737 | 6.5% | |

| 2000 | 19,480 | 9.8% | |

| 2010 | 20,840 | 7.0% | |

| Est. 2016 | 21,524 | [37] | 3.3% |

| Sources:[38]U.S. Decennial Census[39] 2013 Estimate[3] | |||

2010 census

The Oregon Bank Building is one of 13 sites in Klamath Falls listed on the National Register of Historic Places

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 20,840 people, 8,542 households, and 4,876 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,052.0 inhabitants per square mile (406.2/km2). There were 9,595 housing units at an average density of 484.4 per square mile (187.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 83.4% White, 1.0% African American, 4.3% Native American, 1.6% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 4.5% from other races, and 5.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 11.8% of the population.

There were 8,542 households of which 30.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.5% were married couples living together, 13.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 42.9% were non-families. 32.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.35 and the average family size was 2.98.

The median age in the city was 33.6 years. 23.6% of residents were under the age of 18; 14.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25.2% were from 25 to 44; 24.1% were from 45 to 64; and 12.3% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.3% male and 50.7% female.

2000 census

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 19,462 people, 7,916 households, and 4,670 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,089.5/sq mi (420.7/km2). There were 8,722 housing units at an average density of 488.3/sq mi (188.5/km2).

The racial makeup of the city was:

- 85.12% White

- 1.02% African American

- 4.44% Native American

- 1.32% Asian

- 0.13% Pacific Islander

- 4.15% from other races

- 3.83% from two or more races

9.32% of the population are Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 7,916 households out of which:

- 30.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them

- 42.2% were married couples living together

- 11.7% had a female householder with no husband present

- 41.0% were non-families

- 32.4% of all households were made up of individuals

- 11.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older

The average household size was 2.36 and the average family size was 2.99.

The age distribution was:

- 25.5% under the age of 18

- 13.1% from 18 to 24

- 27.2% from 25 to 44

- 21.5% from 45 to 64

- 12.8% who were 65 years of age or older

The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $28,498, and the median income for a family was $37,021. Males had a median income of $31,567 versus $22,313 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,710. About 21.9% of the population and 16.2% of families were below the poverty line, including 26.8% of those under age 18 and 9.5% of those 65 or over.

Government and politics

The Klamath County Courthouse

Klamath Falls is a home rule municipality under the Oregon Constitution, and has been governed by a council–manager form of government since its citizens voted to adopt the current charter in 1972.[40] The city council, which is nonpartisan, has five members, each elected from one of the five wards. They serve four-year terms, which are staggered so that either two or three seats are up for election every two years. The mayor, who is nonpartisan and serves a term of four years, presides over all city council meetings. This official appoints committees, can veto any ordinance not passed with the affirmative vote of at least four council members, and casts tie-breaking votes. The city manager, however, is the administrative head of the city. This official is appointed by the council and serves an indefinite term at the council's pleasure. The municipal judge and the city attorney are appointed on the same basis. Todd Kellstrom has been mayor since 1992, and is currently serving a fifth consecutive term. Nathan Cherpeski is the current city manager.[41]

For the purpose of representation in the state legislature, Klamath Falls is located in the 28th Senate district, represented by Republican Doug Whitsett, and in the 56th House district, represented by Republican Bill Garrard. Federally, Klamath Falls is located in Oregon's 2nd congressional district, which has a Cook Partisan Voting Index of R+10[42]

and is represented by Republican Greg Walden.

Economy

Sky Lakes Medical Center is the largest employer in the area,[citation needed] followed by the Klamath Falls City School District[citation needed] Other major employers are JELD-WEN, Collins Products, Columbia Forest Products, iQor, Klamath County School District, and Oregon Institute of Technology.

Klamath Falls is home to the 173rd Fighter Wing of the Oregon Air National Guard, stationed at Kingsley Field airbase. The 270 Air Traffic Control Squadron resides at Kingsley Field Oregon Air National Guard Base. The 173rd Fighter Wing currently flies F-15 C/D Variants.

Military airbase

Kingsley Field Air National Guard Base also known as Klamath Falls Airport was established in 1928 and is now the home of the 173rd Fighter Wing of the Oregon Air National Guard. Kingsley Field Air National Guard Base has the second largest runway in Oregon (10,301 by 150 feet (3,140 by 46 metres) wide) and was listed as a backup landing strip for the Space Shuttle. As Kingsley Field is a training base for the Oregon Air National Guard, it is normal to hear aircraft throughout Klamath Falls during daylight hours.

Education

Klamath Union High School (KU) 2013 football team in action.

Colleges and universities

- Klamath Community College

- Oregon Institute of Technology

- College of Cosmetology

Public schools

- Klamath Falls and the surrounding area are served by Klamath County School District and the Klamath Falls City School District.

Recreation

Veterans Park on the south shore of the Upper Klamath Lake, downtown Klamath Falls.

Klamath Falls is home to many outdoor winter and summer activities. The nearby Running Y Ranch Resort & hotel features a golf course designed by Arnold Palmer[43] and an ice skating arena. The resort overlooks Upper Klamath Lake. contractCode=NRSO&recAreaId=3132|title=Recreation.gov recreation area details - Upper Klamath Lake - Recreation.gov|author=|date=|website=www.recreation.gov}}</ref> There is also a canoe trail through the wildlife refuge at Rocky Point.

With the help of many passionate community members, Klamath Falls has developed a series of trails in Moore Park. The trail network in and around Moore Park is well loved and heavily used by hikers, cyclists, runners, and others. Users have put countless hours into developing and improving excellent trails that offers varied terrain and vegetation, stunning views of Upper Klamath Lake and the Klamath Basin, and a range of difficulty levels.[44]

The OC&E Woods Line State Trail is a rail trail in the city and is the longest state park in Oregon. Wiard Park, along the OC&E State Trail and operated by the Wiard Memorial Park and Recreation District,[45] is open dawn to dusk from May 1 to October 1. Klamath Falls has a Veterans Memorial Park located downtown along the shore of Lake Ewauna.

Klamath Falls is located on the Pacific Flyway, and large numbers of waterfowl and raptors are seen throughout the year. A large number of bald eagles winter in Bear Valley, located 10 miles (16 km) west of Klamath Falls, near Keno, and the American white pelican shows in great numbers in summer.

Crater Lake National Park is 50 miles (80 km) north of Klamath Falls, and 33-mile (53 km) Rim Drive, which circles the lake, is a favorite of cyclists. Winter cross country skiing and snow shoeing in the park is also very popular. The more-than-mile-high Crater Lake Marathon is an annual event.[46]

Lava Beds National Monument is about 30 miles (48 km) to the southeast of Klamath Falls near the town of Tulelake, California. The Lava Beds provide an excellent opportunity to explore an area that has perhaps the highest concentration of lava tubes. The monument also interprets the Modoc War, including the First Battle of the Stronghold.

Mountain Lakes Wilderness Area, one of the first designated wilderness areas in the United States, lies just to the west of Klamath Falls, providing some excellent opportunities for backpacking and fishing in pristine mountain lakes.

Transportation

Amtrak's Coast Starlight at Klamath Falls station

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, serves Klamath Falls, operating its Coast Starlight daily in both directions between Seattle, Washington, and Los Angeles, California.

Fixed route public transit service is operated by Basin Transit Service, a special service district with an elected board. Oregon POINT connects Klamath Falls with Medford and Brookings, Oregon.[47] Sage Stage provides weekly service to Alturas, California.[48]

The Klamath Falls airport is the location of the Kingsley Field Air National Guard Base, the airport and base are 6 miles (10 km) south of downtown.

Notable people

Sharron Angle (1949–), Nevada politician

Brenda Bakke (1963–), actress

Dennis Bennett (1939–2012), Major League Baseball player

Harry D. Boivin (1904–1999), Speaker of the Oregon House of Representatives and twice President of the Oregon Senate

Ernest C. Brace (1931-2014), pilot

Jeff Bronkey (1965-), Major League Baseball player

Don Pedro Colley (1938–2017), actor

Allison Cook, Miss Oregon 2013.

Ian Dobson (1982-), Team Run Eugene Coach, former Olympic coach for Greek Olympian Alexi Pappas and retired Olympic 5k runner

Chris Eyre (1968–), Sundance Film Festival award winner

Helen J. Frye (1930–2011), Federal District Court judge

Chad Gray (1971–), musician

Rosie Hamlin (1945–2017), singer-songwriter

Ralph Hill (1908–1994), Olympic 5000 meters silver medalist

James Ivory (1928–), Oscar-winning director, screenwriter and producer[49]

Charles S. Moore (1857–1915), Oregon politician

Dan O'Brien (1966–), Olympic gold medalist in Decathlon

Charles O. Porter (1919–2006), Oregon politician

Marty Ravellette (1939–2007), armless hero who lived in Klamath Falls in the 1960s

Laurenne Ross (1988- ), World Cup alpine ski racer from the United States

Janice Romary (1927-2007), U.S. women's Olympic foilist who was the first woman to appear at six Olympic Games

Kim Walker-Smith, neopentecostal worship leader and recording artist

Paul Zahniser (1896–1964), Major League Baseball player

Sister city

Klamath Falls has one sister city,[50] as designated by Sister Cities International:

Rotorua, New Zealand

Rotorua, New Zealand

Radio stations

.mw-parser-output div.columns-2 div.column{float:left;width:50%;min-width:300px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-3 div.column{float:left;width:33.3%;min-width:200px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-4 div.column{float:left;width:25%;min-width:150px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-5 div.column{float:left;width:20%;min-width:120px}

|

|

|

|

See also

- Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuges Complex

- Klamath County Event Center

- Klamath Falls Airport

- Klamath Lake

- Klamath Reclamation Project

- Klamath River

- OC&E Woods Line State Trail

References

^ ab "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-01-24. Retrieved 2012-12-21..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

^ ab "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2014-05-22. Retrieved 2014-10-02.

^ ab "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

^ "Vocabulary". Klamath Tribes Language Project. The Klamath Tribes. Archived from the original on 2013-08-20. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

^ History of Klamath Falls The City of Klamath Falls webpage. Accessed 28 May 2014.

^ "2010 Census profiles: Oregon cities alphabetically H-L" (PDF). Portland State University Population Research Center. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

^ McArthur, p. 580

^ McArthur, p. 541

^ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

^ "The Klamath" (PDF). World Wisdom online library. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

^ Name of Tiwishkeni Archived 2009-03-09 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Hell With the Fire Out: A History of the Modoc War by Anthony Quinn

^ "California and the Indian Wars: The Modoc War, 1872-1873". Militarymuseum.org. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

^ "Applegate Trail: the Southern Route of the Oregon Trail". www.webtrail.com.

^ OHP, Putting Nature to Work: Living in Linkville

^ OHP, Klamath Homestead Drawing

^ Railroad Logging in the Klamath Country

^ "Earthquakes in Oregon State". Crew.org. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

^ "The Klamath Bucket Brigade". The Klamath Bucket Brigade. Archived from the original on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

^ Michael Milstein (2002-10-27). The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon http://www.pelicannetwork.net/salmon.tappingtrinity.htm.A new federal estimate puts the toll of last month's fish kill at 33,000, most of them chinook salmon but says that number is conservative.

Missing or empty|title=(help)

^ ab Becker, Jo; Gellman, Barton (2007-06-27). "Leaving No Tracks". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15.

^ Michael Milstein (2002-10-27). The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon http://www.pelicannetwork.net/salmon.tappingtrinity.htm.As much as 90 percent of the Trinity's water, which would otherwise flow into the Klamath and out to sea, instead rushes south toward California's thirsty center.

Missing or empty|title=(help)

^ Broader Approach Needed for Protection And Recovery of Fish in Klamath River Basin,

^ abc "Geothermal in Oregon" (PDF). Geo-Heat Center, Oregon Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

^ Rachel Sakata (September 26, 2012). "Klamath Falls PM2.5 Attainment Plan" (PDF). pp. 1, 4.

^ "US town uses geothermal energy to stay warm". AP. 2010-03-22. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

^ "City of Klamath Falls :: City of Sunshine". www.klamathfalls.city.

^ Team, National Weather Service Corporate Image Web. "National Weather Service - NWS Medford". w2.weather.gov.

^ "Klamath Falls 2 SSW, Oregon - Period of Record General Climate Summary - Temperature". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

^ "Klamath Falls 2 SSW, Oregon - Freeze-Free Probabilities". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

^ "Klamath Falls 2 SSW, Oregon - Spring Freeze Probabilities". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

^ "Klamath Falls 2 SSW, Oregon - Fall Freeze Probabilities". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

^ "Klamath Falls 2 SSW, Oregon - Climate Summary". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

^ "Klamath Falls 2 SSW, Oregon - Period of Record General Climate Summary - Precipitation". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

^ Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850-1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 211.

^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

^ The Revised Charter of 1972 for the City of Klamath Falls.

^ [1].

^ "Introducing The Cook Political Report Partisan Voting Index (PVI) for the 111th Congress". The Cook Political Report. Archived from the original on 2011-09-02.

^ "Sweet16.pdf" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-07-08.

^ "Moore Mountain Area Trails". klamathtrails.org. 22 April 2012.

^ Problems of the urban fringe, Volume 1. University of Oregon. Bureau of Municipal Research and Service, Oregon. Legislative Assembly. Interim Committee on Local Government and Urban Area Problems. 1957. p. 25.

^ "Crater Lake Rim Runs". Crater Lake Rim Runs. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

^ "SouthWest POINT - Oregon POINT". oregon-point.com.

^ "Sage Stage - Modoc County, California : Klamath Falls". sagestage.com.

^ "James Ivory Biography". Fandango.com. 1928-06-07. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-05-02. Retrieved 2006-06-10.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

Sources

- McArthur, Lewis A., and McArthur, Lewis L. (2003) [1928]. Oregon Geographic Names, 7th ed. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press.

ISBN 978-0-87595-277-2.

"Oregon History Project". Oregon History Society. 1946-12-18. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Klamath Falls, Oregon. |

Klamath Falls travel guide from Wikivoyage

Klamath Falls travel guide from Wikivoyage

Entry for Klamath Falls in the Oregon Blue Book

Where are the falls? (flyer prepared by the Klamath County Museum, August 2008)- Basin Transit Service