Propagator

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

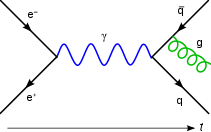

Feynman diagram |

History |

Background

|

Symmetries

|

Tools

|

Equations

|

Standard Model

|

Incomplete theories

|

Scientists

|

In quantum mechanics and quantum field theory, the propagator is a function that specifies the probability amplitude for a particle to travel from one place to another in a given time, or to travel with a certain energy and momentum. In Feynman diagrams, which serve to calculate the rate of collisions in quantum field theory, virtual particles contribute their propagator to the rate of the scattering event described by the respective diagram. These may also be viewed as the inverse of the wave operator appropriate to the particle, and are, therefore, often called (causal) Green's functions (called "causal" to distinguish it from the elliptic Laplacian Green's function).[1][2]

Contents

1 Non-relativistic propagators

1.1 Basic examples: propagator of free particle and harmonic oscillator

2 Relativistic propagators

2.1 Scalar propagator

2.2 Position space

2.2.1 Causal propagators

2.2.1.1 Retarded propagator

2.2.1.2 Advanced propagator

2.2.2 Feynman propagator

2.3 Momentum space propagator

2.4 Faster than light?

2.4.1 Explanation using limits

2.5 Propagators in Feynman diagrams

2.6 Other theories

2.6.1 Spin 1⁄2

2.6.2 Spin 1

2.7 Graviton propagator

3 Related singular functions

3.1 Solutions to the Klein–Gordon equation

3.1.1 Pauli–Jordan function

3.1.2 Positive and negative frequency parts (cut propagators)

3.1.3 Auxiliary function

3.2 Green's functions for the Klein–Gordon equation

4 Notes

5 References

6 External links

Non-relativistic propagators

In non-relativistic quantum mechanics, the propagator gives the probability amplitude for a particle to travel from one spatial point at one time to another spatial point at a later time. It is the Green's function (fundamental solution) for the Schrödinger equation. This means that, if a system has Hamiltonian H, then the appropriate propagator is a function

- G(x,t;x′,t′)=1iℏΘ(t−t′)K(x,t;x′,t′){displaystyle G(x,t;x',t')={frac {1}{ihbar }}Theta (t-t')K(x,t;x',t')}

satisfying

- (iℏ∂∂t−Hx)G(x,t;x′,t′)=δ(x−x′)δ(t−t′) ,{displaystyle left(ihbar {frac {partial }{partial t}}-H_{x}right)G(x,t;x',t')=delta (x-x')delta (t-t')~,}

where Hx denotes the Hamiltonian written in terms of the x coordinates, δ(x) denotes the Dirac delta-function, Θ(t) is the Heaviside step function and K(x, t ;x′, t′) is the kernel of the above Schrödinger differential operator in the big parenthesis, often referred to as the propagator instead of G in this context, and henceforth in this article. (cf. Duhamel's principle.)

This propagator may also be written as the transition amplitude

- K(x,t;x′,t′)=⟨x∣U^(t,t′)∣x′⟩,{displaystyle K(x,t;x',t')=leftlangle xmid {hat {U}}(t,t')mid x'rightrangle ,}

where Û(t, t′) is the unitary time-evolution operator for the system taking states at time t′ to states at time t. Note that

limt→t′K(x,t;x′,t′)=δ(x−x′){displaystyle lim _{tto t'}K(x,t;x',t')=delta (x-x')}

The quantum mechanical propagator may also be found by using a path integral,

- K(x,t;x′,t′)=∫exp[iℏ∫tt′L(q˙,q,t)dt]D[q(t)]{displaystyle K(x,t;x',t')=int exp left[{frac {i}{hbar }}int _{t}^{t'}L({dot {q}},q,t),dtright]D[q(t)]}

where the boundary conditions of the path integral include q(t) = x, q(t′) = x′. Here L denotes the Lagrangian of the system. The paths that are summed over move only forwards in time, and are integrated with the differential D[q(t)]{displaystyle D[q(t)]}![{displaystyle D[q(t)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7702e95120aafa87851eca2a469c03b55f54d391)

In non-relativistic quantum mechanics, the propagator lets you find the wave function of a system given an initial wave function and a time interval. The new wave function is given by the equation

- ψ(x,t)=∫−∞∞ψ(x′,t′)K(x,t;x′,t′)dx′.{displaystyle psi (x,t)=int _{-infty }^{infty }psi (x',t')K(x,t;x',t'),dx'.}

If K(x,t;x′,t′) only depends on the difference x − x′, this is a convolution of the initial wave function and the propagator. This kernel is the kernel of integral transform.

Basic examples: propagator of free particle and harmonic oscillator

For a time-translationally invariant system, the propagator only depends on the time difference t − t′, so it may be rewritten as

- K(x,t;x′,t′)=K(x,x′;t−t′).{displaystyle K(x,t;x',t')=K(x,x';t-t').}

The propagator of a one-dimensional free particle, with the far-right expression obtained via saddle-point methods, is then

K(x,x′;t)=12π∫−∞+∞dkeik(x−x′)e−iℏk2t2m=(m2πiℏt)12e−m(x−x′)22iℏt.{displaystyle K(x,x';t)={frac {1}{2pi }}int _{-infty }^{+infty }dk,e^{ik(x-x')}e^{-{frac {ihbar k^{2}t}{2m}}}=left({frac {m}{2pi ihbar t}}right)^{frac {1}{2}}e^{-{frac {m(x-x')^{2}}{2ihbar t}}}.}

Similarly, the propagator of a one-dimensional quantum harmonic oscillator is the Mehler kernel,[3][4]

K(x,x′;t)=(mω2πiℏsinωt)12exp(−mω((x2+x′2)cosωt−2xx′)2iℏsinωt) .{displaystyle K(x,x';t)=left({frac {momega }{2pi ihbar sin omega t}}right)^{frac {1}{2}}exp left(-{frac {momega ((x^{2}+x'^{2})cos omega t-2xx')}{2ihbar sin omega t}}right)~.}

The latter may be obtained from the previous free particle result upon making use of van Kortryk's SU(2) Lie-group identity,

- exp(−itℏ(12m p2+12 mω2x2)){displaystyle exp left(-{frac {it}{hbar }}left({frac {1}{2m}}~{mathsf {p}}^{2}+{frac {1}{2}}~momega ^{2}{mathsf {x}}^{2}right)right)}

- =exp(−imω2ℏ x2tan(ωt2))exp(−i2mωℏ p2sin(ωt))exp(−imω2ℏ x2tan(ωt2)) ,{displaystyle =exp left(-{frac {imomega }{2hbar }}~{mathsf {x}}^{2}tan left({frac {omega t}{2}}right)right)exp left(-{frac {i}{2momega hbar }}~{mathsf {p}}^{2}sin left(omega tright)right)exp left(-{frac {imomega }{2hbar }}~{mathsf {x}}^{2}tan left({frac {omega t}{2}}right)right)~,}

- =exp(−imω2ℏ x2tan(ωt2))exp(−i2mωℏ p2sin(ωt))exp(−imω2ℏ x2tan(ωt2)) ,{displaystyle =exp left(-{frac {imomega }{2hbar }}~{mathsf {x}}^{2}tan left({frac {omega t}{2}}right)right)exp left(-{frac {i}{2momega hbar }}~{mathsf {p}}^{2}sin left(omega tright)right)exp left(-{frac {imomega }{2hbar }}~{mathsf {x}}^{2}tan left({frac {omega t}{2}}right)right)~,}

valid for operators x{displaystyle {mathsf {x}}}

![[{mathsf {x}},{mathsf {p}}]=ihbar](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c34a6d2b647663cd1951f44edb2c69556a1c756a)

For the N-dimensional case, the propagator can be simply obtained by the product

- K(x→,x→′;t)=∏q=1NK(xq,xq′;t) .{displaystyle K({vec {x}},{vec {x}}';t)=prod _{q=1}^{N}K(x_{q},x_{q}';t)~.}

Relativistic propagators

In relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum field theory the propagators are Lorentz invariant. They give the amplitude for a particle to travel between two spacetime points.

Scalar propagator

In quantum field theory, the theory of a free (non-interacting) scalar field is a useful and simple example which serves to illustrate the concepts needed for more complicated theories. It describes spin zero particles. There are a number of possible propagators for free scalar field theory. We now describe the most common ones.

Position space

The position space propagators are Green's functions for the Klein–Gordon equation. This means they are functions G(x, y) which satisfy

- (◻x+m2)G(x,y)=−δ(x−y){displaystyle (square _{x}+m^{2})G(x,y)=-delta (x-y)}

where:

x, y are two points in Minkowski spacetime.

◻x=∂2∂t2−∇2{displaystyle square _{x}={tfrac {partial ^{2}}{partial t^{2}}}-nabla ^{2}}is the d'Alembertian operator acting on the x coordinates.

δ(x − y) is the Dirac delta-function.

(As typical in relativistic quantum field theory calculations, we use units where the speed of light, c, and Planck's reduced constant, ħ, are set to unity.)

We shall restrict attention to 4-dimensional Minkowski spacetime. We can perform a Fourier transform of the equation for the propagator, obtaining

- (−p2+m2)G(p)=−1.{displaystyle left(-p^{2}+m^{2}right)G(p)=-1.}

This equation can be inverted in the sense of distributions noting that the equation xf(x)=1 has the solution, (see Sokhotski-Plemelj theorem)

- f(x)=1x±iε=1x∓iπδ(x),{displaystyle f(x)={frac {1}{xpm ivarepsilon }}={frac {1}{x}}mp ipi delta (x),}

with ε implying the limit to zero. Below, we discuss the right choice of the sign arising from causality requirements.

The solution is

G(x,y)=1(2π)4∫d4pe−ip(x−y)p2−m2±iε ,{displaystyle G(x,y)={frac {1}{(2pi )^{4}}}int d^{4}p,{frac {e^{-ip(x-y)}}{p^{2}-m^{2}pm ivarepsilon }}~,}

where

- p(x−y):=p0(x0−y0)−p→⋅(x→−y→){displaystyle p(x-y):=p_{0}(x^{0}-y^{0})-{vec {p}}cdot ({vec {x}}-{vec {y}})}

is the 4-vector inner product.

The different choices for how to deform the integration contour in the above expression lead to various forms for the propagator. The choice of contour is usually phrased in terms of the p0{displaystyle p_{0}}

The integrand then has two poles at

- p0=±p→2+m2{displaystyle p_{0}=pm {sqrt {{vec {p}}^{2}+m^{2}}}}

so different choices of how to avoid these lead to different propagators.

Causal propagators

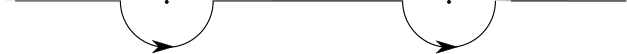

Retarded propagator

A contour going clockwise over both poles gives the causal retarded propagator. This is zero if x-y is spacelike or if x ⁰< y ⁰ (i.e. if y is to the future of x).

This choice of contour is equivalent to calculating the limit,

- Gret(x,y)=limε→01(2π)4∫d4pe−ip(x−y)(p0+iε)2−p→2−m2=−Θ(x−y)2πδ(τxy2)+Θ(x−y)Θ(τxy2)mJ1(mτxy)4πτxy{displaystyle G_{text{ret}}(x,y)=lim _{varepsilon to 0}{frac {1}{(2pi )^{4}}}int d^{4}p,{frac {e^{-ip(x-y)}}{(p_{0}+ivarepsilon )^{2}-{vec {p}}^{2}-m^{2}}}=-{frac {Theta (x-y)}{2pi }}delta (tau _{xy}^{2})+Theta (x-y)Theta (tau _{xy}^{2}){frac {mJ_{1}(mtau _{xy})}{4pi tau _{xy}}}}

Here

- Θ(x):={1x≥00x<0{displaystyle Theta (x):={begin{cases}1&xgeq 0\0&x<0end{cases}}}

is the Heaviside step function and

- τxy:=(x0−y0)2−(x→−y→)2{displaystyle tau _{xy}:={sqrt {(x^{0}-y^{0})^{2}-({vec {x}}-{vec {y}})^{2}}}}

is the proper time from x to y and J1{displaystyle J_{1}}

y0<x0{displaystyle y^{0}<x^{0}}and τxy2≥0 .{displaystyle tau _{xy}^{2}geq 0~.}

This expression can be related to the vacuum expectation value of the commutator of the free scalar field operator,

- Gret(x,y)=i⟨0|[Φ(x),Φ(y)]|0⟩Θ(x0−y0){displaystyle G_{text{ret}}(x,y)=ilangle 0|left[Phi (x),Phi (y)right]|0rangle Theta (x^{0}-y^{0})}

where

- [Φ(x),Φ(y)]:=Φ(x)Φ(y)−Φ(y)Φ(x){displaystyle left[Phi (x),Phi (y)right]:=Phi (x)Phi (y)-Phi (y)Phi (x)}

is the commutator.

Advanced propagator

A contour going anti-clockwise under both poles gives the causal advanced propagator. This is zero if x-y is spacelike or if x ⁰> y ⁰ (i.e. if y is to the past of x).

This choice of contour is equivalent to calculating the limit[5]

- Gadv(x,y)=limε→01(2π)4∫d4pe−ip(x−y)(p0−iε)2−p→2−m2=−Θ(y−x)2πδ(τxy2)+Θ(y−x)Θ(τxy2)mJ1(mτxy)4πτxy{displaystyle G_{text{adv}}(x,y)=lim _{varepsilon to 0}{frac {1}{(2pi )^{4}}}int d^{4}p,{frac {e^{-ip(x-y)}}{(p_{0}-ivarepsilon )^{2}-{vec {p}}^{2}-m^{2}}}=-{frac {Theta (y-x)}{2pi }}delta (tau _{xy}^{2})+Theta (y-x)Theta (tau _{xy}^{2}){frac {mJ_{1}(mtau _{xy})}{4pi tau _{xy}}}}

This expression can also be expressed in terms of the vacuum expectation value of the commutator of the free scalar field.

In this case,

- Gadv(x,y)=−i⟨0|[Φ(x),Φ(y)]|0⟩Θ(y0−x0) .{displaystyle G_{text{adv}}(x,y)=-ilangle 0|left[Phi (x),Phi (y)right]|0rangle Theta (y^{0}-x^{0})~.}

Feynman propagator

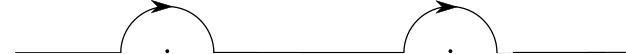

A contour going under the left pole and over the right pole gives the Feynman propagator.

This choice of contour is equivalent to calculating the limit[6]

- GF(x,y)=limε→01(2π)4∫d4pe−ip(x−y)p2−m2+iε={−14πδ(s)+m8πsH1(2)(ms)s≥0−im4π2−sK1(m−s)s<0.{displaystyle G_{F}(x,y)=lim _{varepsilon to 0}{frac {1}{(2pi )^{4}}}int d^{4}p,{frac {e^{-ip(x-y)}}{p^{2}-m^{2}+ivarepsilon }}={begin{cases}-{frac {1}{4pi }}delta (s)+{frac {m}{8pi {sqrt {s}}}}H_{1}^{(2)}(m{sqrt {s}})&sgeq 0\-{frac {im}{4pi ^{2}{sqrt {-s}}}}K_{1}(m{sqrt {-s}})&s<0.end{cases}}}

Here

- s:=(x0−y0)2−(x→−y→)2,{displaystyle s:=(x^{0}-y^{0})^{2}-({vec {x}}-{vec {y}})^{2},}

where x and y are two points in Minkowski spacetime, and the dot in the exponent is a four-vector inner product. H1(2) is a Hankel function and K1 is a modified Bessel function.

This expression can be derived directly from the field theory as the vacuum expectation value of the time-ordered product of the free scalar field, that is, the product always taken such that the time ordering of the spacetime points is the same,

- GF(x−y)=−i⟨0|T(Φ(x)Φ(y))|0⟩=−i⟨0|[Θ(x0−y0)Φ(x)Φ(y)+Θ(y0−x0)Φ(y)Φ(x)]|0⟩.{displaystyle {begin{aligned}G_{F}(x-y)&=-ilangle 0|T(Phi (x)Phi (y))|0rangle \[4pt]&=-ileftlangle 0|left[Theta (x^{0}-y^{0})Phi (x)Phi (y)+Theta (y^{0}-x^{0})Phi (y)Phi (x)right]|0rightrangle .end{aligned}}}

This expression is Lorentz invariant, as long as the field operators commute with one another when the points x and y are separated by a spacelike interval.

The usual derivation is to insert a complete set of single-particle momentum states between the fields with Lorentz covariant normalization, and to then show that the Θ functions providing the causal time ordering may be obtained by a contour integral along the energy axis, if the integrand is as above (hence the infinitesimal imaginary part), to move the pole off the real line.

The propagator may also be derived using the path integral formulation of quantum theory.

Momentum space propagator

The Fourier transform of the position space propagators can be thought of as propagators in momentum space. These take a much simpler form than the position space propagators.

They are often written with an explicit ε term although this is understood to be a reminder about which integration contour is appropriate (see above). This ε term is included to incorporate boundary conditions and causality (see below).

For a 4-momentum p the causal and Feynman propagators in momentum space are:

- G~ret(p)=1(p0+iε)2−p→2−m2{displaystyle {tilde {G}}_{text{ret}}(p)={frac {1}{(p_{0}+ivarepsilon )^{2}-{vec {p}}^{2}-m^{2}}}}

- G~adv(p)=1(p0−iε)2−p→2−m2{displaystyle {tilde {G}}_{text{adv}}(p)={frac {1}{(p_{0}-ivarepsilon )^{2}-{vec {p}}^{2}-m^{2}}}}

- G~F(p)=1p2−m2+iε.{displaystyle {tilde {G}}_{F}(p)={frac {1}{p^{2}-m^{2}+ivarepsilon }}.}

For purposes of Feynman diagram calculations, it is usually convenient to write these with an additional overall factor of −i (conventions vary).

Faster than light?

The Feynman propagator has some properties that seem baffling at first. In particular, unlike the commutator, the propagator is nonzero outside of the light cone, though it falls off rapidly for spacelike intervals. Interpreted as an amplitude for particle motion, this translates to the virtual particle travelling faster than light. It is not immediately obvious how this can be reconciled with causality: can we use faster-than-light virtual particles to send faster-than-light messages?

The answer is no: while in classical mechanics the intervals along which particles and causal effects can travel are the same, this is no longer true in quantum field theory, where it is commutators that determine which operators can affect one another.

So what does the spacelike part of the propagator represent? In QFT the vacuum is an active participant, and particle numbers and field values are related by an uncertainty principle; field values are uncertain even for particle number zero. There is a nonzero probability amplitude to find a significant fluctuation in the vacuum value of the field Φ(x) if one measures it locally (or, to be more precise, if one measures an operator obtained by averaging the field over a small region). Furthermore, the dynamics of the fields tend to favor spatially correlated fluctuations to some extent. The nonzero time-ordered product for spacelike-separated fields then just measures the amplitude for a nonlocal correlation in these vacuum fluctuations, analogous to an EPR correlation. Indeed, the propagator is often called a two-point correlation function for the free field.

Since, by the postulates of quantum field theory, all observable operators commute with each other at spacelike separation, messages can no more be sent through these correlations than they can through any other EPR correlations; the correlations are in random variables.

Regarding virtual particles, the propagator at spacelike separation can be thought of as a means of calculating the amplitude for creating a virtual particle-antiparticle pair that eventually disappears into the vacuum, or for detecting a virtual pair emerging from the vacuum. In Feynman's language, such creation and annihilation processes are equivalent to a virtual particle wandering backward and forward through time, which can take it outside of the light cone. However, no signaling back in time is allowed.

Explanation using limits

This can be made clearer by writing the propagator in the following form for a massless photon,

- GFε(x,y)=ε(x−y)2+iε2 .{displaystyle G_{F}^{varepsilon }(x,y)={frac {varepsilon }{(x-y)^{2}+ivarepsilon ^{2}}}~.}

This is the usual definition but normalised by a factor of ε{displaystyle varepsilon }

One sees that

GFε(x,y)=1ε{displaystyle G_{F}^{varepsilon }(x,y)={frac {1}{varepsilon }}}if (x−y)2=0{displaystyle (x-y)^{2}=0}

and

limε→0GFε(x,y)=0{displaystyle lim _{varepsilon rightarrow 0}G_{F}^{varepsilon }(x,y)=0}if (x−y)2≠0{displaystyle (x-y)^{2}neq 0}

Hence this means a single photon will always stay on the light cone. It is also shown that the total probability for a photon at any time must be normalised by the reciprocal of the following factor:

- limε→0∫|GFε(0,x)|2dx3=limε→0∫ε2(x2−t2)2+ε4dx3=2π2|t| .{displaystyle lim _{varepsilon rightarrow 0}int left|G_{F}^{varepsilon }(0,x)right|^{2},dx^{3}=lim _{varepsilon rightarrow 0}int {frac {varepsilon ^{2}}{(mathbf {x} ^{2}-t^{2})^{2}+varepsilon ^{4}}},dx^{3}=2pi ^{2}|t|~.}

We see that the parts outside the light cone usually are zero in the limit and only are important in Feynman diagrams.

Propagators in Feynman diagrams

The most common use of the propagator is in calculating probability amplitudes for particle interactions using Feynman diagrams. These calculations are usually carried out in momentum space. In general, the amplitude gets a factor of the propagator for every internal line, that is, every line that does not represent an incoming or outgoing particle in the initial or final state. It will also get a factor proportional to, and similar in form to, an interaction term in the theory's Lagrangian for every internal vertex where lines meet. These prescriptions are known as Feynman rules.

Internal lines correspond to virtual particles. Since the propagator does not vanish for combinations of energy and momentum disallowed by the classical equations of motion, we say that the virtual particles are allowed to be off shell. In fact, since the propagator is obtained by inverting the wave equation, in general, it will have singularities on the shell.

The energy carried by the particle in the propagator can even be negative. This can be interpreted simply as the case in which, instead of a particle going one way, its antiparticle is going the other way, and therefore carrying an opposing flow of positive energy. The propagator encompasses both possibilities. It does mean that one has to be careful about minus signs for the case of fermions, whose propagators are not even functions in the energy and momentum (see below).

Virtual particles conserve energy and momentum. However, since they can be off the shell, wherever the diagram contains a closed loop, the energies and momenta of the virtual particles participating in the loop will be partly unconstrained, since a change in a quantity for one particle in the loop can be balanced by an equal and opposite change in another. Therefore, every loop in a Feynman diagram requires an integral over a continuum of possible energies and momenta. In general, these integrals of products of propagators can diverge, a situation that must be handled by the process of renormalization.

Other theories

Spin 1⁄2

If the particle possesses spin then its propagator is in general somewhat more complicated, as it will involve the particle's spin or polarization indices. The differential equation satisfied by the propagator for a spin 1⁄2 particle is given by[7]

- (i∇̸′−m)SF(x′,x)=I4δ4(x′−x),{displaystyle (inot nabla '-m)S_{F}(x',x)=I_{4}delta ^{4}(x'-x),}

where I4 is the unit matrix in four dimensions, and employing the Feynman slash notation. This is the Dirac equation for a delta function source in spacetime. Using the momentum representation,

- SF(x′,x)=∫d4p(2π)4exp[−ip⋅(x′−x)]S~F(p),{displaystyle S_{F}(x',x)=int {frac {d^{4}p}{(2pi )^{4}}}exp {left[-ipcdot (x'-x)right]}{tilde {S}}_{F}(p),}

the equation becomes

- (i∇̸′−m)∫d4p(2π)4S~F(p)exp[−ip⋅(x′−x)]=∫d4p(2π)4(p̸−m)S~F(p)exp[−ip⋅(x′−x)]=∫d4p(2π)4I4exp[−ip⋅(x′−x)]=I4δ4(x′−x),{displaystyle {begin{aligned}&(inot nabla '-m)int {frac {d^{4}p}{(2pi )^{4}}}{tilde {S}}_{F}(p)exp {left[-ipcdot (x'-x)right]}\[6pt]={}&int {frac {d^{4}p}{(2pi )^{4}}}(not p-m){tilde {S}}_{F}(p)exp {left[-ipcdot (x'-x)right]}\[6pt]={}&int {frac {d^{4}p}{(2pi )^{4}}}I_{4}exp {left[-ipcdot (x'-x)right]}\[6pt]={}&I_{4}delta ^{4}(x'-x),end{aligned}}}

where on the right-hand side an integral representation of the four-dimensional delta function is used. Thus

- (p̸−mI4)S~F(p)=I4.{displaystyle (not p-mI_{4}){tilde {S}}_{F}(p)=I_{4}.}

By multiplying from the left with

- (p̸+m){displaystyle (not p+m)}

(dropping unit matrices from the notation) and using properties of the gamma matrices,

- p̸p̸=12(p̸p̸+p̸p̸)=12(γμpμγνpν+γνpνγμpμ)=12(γμγν+γνγμ)pμpν=gμνpμpν=pνpν=p2,{displaystyle {begin{aligned}not pnot p&={frac {1}{2}}(not pnot p+not pnot p)\[6pt]&={frac {1}{2}}(gamma _{mu }p^{mu }gamma _{nu }p^{nu }+gamma _{nu }p^{nu }gamma _{mu }p^{mu })\[6pt]&={frac {1}{2}}(gamma _{mu }gamma _{nu }+gamma _{nu }gamma _{mu })p^{mu }p^{nu }\[6pt]&=g_{mu nu }p^{mu }p^{nu }=p_{nu }p^{nu }=p^{2},end{aligned}}}

the momentum-space propagator used in Feynman diagrams for a Dirac field representing the electron in quantum electrodynamics is found to have form

- S~F(p)=(p̸+m)p2−m2+iε=(γμpμ+m)p2−m2+iε.{displaystyle {tilde {S}}_{F}(p)={frac {(not p+m)}{p^{2}-m^{2}+ivarepsilon }}={frac {(gamma ^{mu }p_{mu }+m)}{p^{2}-m^{2}+ivarepsilon }}.}

The iε downstairs is a prescription for how to handle the poles in the complex p0-plane. It automatically yields the Feynman contour of integration by shifting the poles appropriately. It is sometimes written

- S~F(p)=1γμpμ−m+iε=1p̸−m+iε{displaystyle {tilde {S}}_{F}(p)={1 over gamma ^{mu }p_{mu }-m+ivarepsilon }={1 over not p-m+ivarepsilon }}

for short. It should be remembered that this expression is just shorthand notation for (γμpμ − m)−1. "One over matrix" is otherwise nonsensical. In position space one has

- SF(x−y)=∫d4p(2π)4e−ip⋅(x−y)γμpμ+mp2−m2+iε=(γμ(x−y)μ|x−y|5+m|x−y|3)J1(m|x−y|).{displaystyle S_{F}(x-y)=int {frac {d^{4}p}{(2pi )^{4}}},e^{-ipcdot (x-y)}{frac {gamma ^{mu }p_{mu }+m}{p^{2}-m^{2}+ivarepsilon }}=left({frac {gamma ^{mu }(x-y)_{mu }}{|x-y|^{5}}}+{frac {m}{|x-y|^{3}}}right)J_{1}(m|x-y|).}

This is related to the Feynman propagator by

- SF(x−y)=(i∂̸+m)GF(x−y){displaystyle S_{F}(x-y)=(inot partial +m)G_{F}(x-y)}

where ∂̸:=γμ∂μ{displaystyle not partial :=gamma ^{mu }partial _{mu }}

Spin 1

The propagator for a gauge boson in a gauge theory depends on the choice of convention to fix the gauge. For the gauge used by Feynman and Stueckelberg, the propagator for a photon is

- −igμνp2+iε.{displaystyle {-ig^{mu nu } over p^{2}+ivarepsilon }.}

The propagator for a massive vector field can be derived from the Stueckelberg Lagrangian. The general form with gauge parameter λ reads

- gμν−kμkνm2k2−m2+iε+kμkνm2k2−m2λ+iε.{displaystyle {frac {g_{mu nu }-{frac {k_{mu }k_{nu }}{m^{2}}}}{k^{2}-m^{2}+ivarepsilon }}+{frac {frac {k_{mu }k_{nu }}{m^{2}}}{k^{2}-{frac {m^{2}}{lambda }}+ivarepsilon }}.}

With this general form one obtains the propagator in unitary gauge for λ = 0, the propagator in Feynman or 't Hooft gauge for λ = 1 and in Landau or Lorenz gauge for λ = ∞. There are also other notations where the gauge parameter is the inverse of λ. The name of the propagator, however, refers to its final form and not necessarily to the value of the gauge parameter.

Unitary gauge:

- gμν−kμkνm2k2−m2+iε.{displaystyle {frac {g_{mu nu }-{frac {k_{mu }k_{nu }}{m^{2}}}}{k^{2}-m^{2}+ivarepsilon }}.}

Feynman ('t Hooft) gauge:

- gμνk2−m2+iε.{displaystyle {frac {g_{mu nu }}{k^{2}-m^{2}+ivarepsilon }}.}

Landau (Lorenz) gauge:

- gμν−kμkνk2k2−m2+iε.{displaystyle {frac {g_{mu nu }-{frac {k_{mu }k_{nu }}{k^{2}}}}{k^{2}-m^{2}+ivarepsilon }}.}

Graviton propagator

The graviton propagator for Minkowski space in general relativity is

- G=P2k2−Ps02k2,{displaystyle G={frac {{mathcal {P}}^{2}}{k^{2}}}-{frac {{mathcal {P}}_{s}^{0}}{2k^{2}}},}

where P2{displaystyle {mathcal {P}}^{2}}

The graviton propagator for (Anti) de Sitter space is

- G=P2k2+2H2−Ps02(k2−4H2),{displaystyle G={frac {{mathcal {P}}^{2}}{k^{2}+2H^{2}}}-{frac {{mathcal {P}}_{s}^{0}}{2(k^{2}-4H^{2})}},}

where H{displaystyle H}

Related singular functions

The scalar propagators are Green's functions for the Klein–Gordon equation. There are related singular functions which are important in quantum field theory. We follow the notation in Bjorken and Drell.[9] See also Bogolyubov and Shirkov (Appendix A). These functions are most simply defined in terms of the vacuum expectation value of products of field operators.

Solutions to the Klein–Gordon equation

Pauli–Jordan function

The commutator of two scalar field operators defines the Pauli–Jordan function Δ(x−y){displaystyle Delta (x-y)}

- ⟨0|[Φ(x),Φ(y)]|0⟩=iΔ(x−y){displaystyle langle 0|left[Phi (x),Phi (y)right]|0rangle =i,Delta (x-y)}

with

- Δ(x−y)=Gadv(x−y)−Gret(x−y){displaystyle ,Delta (x-y)=G_{text{adv}}(x-y)-G_{text{ret}}(x-y)}

This satisfies

- Δ(x−y)=−Δ(y−x){displaystyle Delta (x-y)=-Delta (y-x)}

and is zero if (x−y)2<0{displaystyle (x-y)^{2}<0}

Positive and negative frequency parts (cut propagators)

We can define the positive and negative frequency parts of Δ(x−y){displaystyle Delta (x-y)}

This allows us to define the positive frequency part:

- Δ+(x−y)=⟨0|Φ(x)Φ(y)|0⟩,{displaystyle Delta _{+}(x-y)=langle 0|Phi (x)Phi (y)|0rangle ,}

and the negative frequency part:

- Δ−(x−y)=⟨0|Φ(y)Φ(x)|0⟩.{displaystyle Delta _{-}(x-y)=langle 0|Phi (y)Phi (x)|0rangle .}

These satisfy[9]

- iΔ=Δ+−Δ−{displaystyle ,iDelta =Delta _{+}-Delta _{-}}

and

- (◻x+m2)Δ±(x−y)=0.{displaystyle (Box _{x}+m^{2})Delta _{pm }(x-y)=0.}

Auxiliary function

The anti-commutator of two scalar field operators defines Δ1(x−y){displaystyle Delta _{1}(x-y)}

- ⟨0|{Φ(x),Φ(y)}|0⟩=Δ1(x−y){displaystyle langle 0|left{Phi (x),Phi (y)right}|0rangle =Delta _{1}(x-y)}

with

- Δ1(x−y)=Δ+(x−y)+Δ−(x−y).{displaystyle ,Delta _{1}(x-y)=Delta _{+}(x-y)+Delta _{-}(x-y).}

This satisfies Δ1(x−y)=Δ1(y−x).{displaystyle ,Delta _{1}(x-y)=Delta _{1}(y-x).}

Green's functions for the Klein–Gordon equation

The retarded, advanced and Feynman propagators defined above are all Green's functions for the Klein–Gordon equation.

They are related to the singular functions by[9]

- Gret(x−y)=−Δ(x−y)Θ(x0−y0){displaystyle G_{text{ret}}(x-y)=-Delta (x-y)Theta (x_{0}-y_{0})}

- Gadv(x−y)=Δ(x−y)Θ(y0−x0){displaystyle G_{text{adv}}(x-y)=Delta (x-y)Theta (y_{0}-x_{0})}

- 2GF(x−y)=−iΔ1(x−y)+ε(x0−y0)Δ(x−y){displaystyle 2G_{F}(x-y)=-i,Delta _{1}(x-y)+varepsilon (x_{0}-y_{0}),Delta (x-y)}

where

- ε(x0−y0)=2Θ(x0−y0)−1.{displaystyle ,varepsilon (x_{0}-y_{0})=2Theta (x_{0}-y_{0})-1.}

Notes

^ The mathematics of PDEs and the wave equation, p 32., Michael P. Lamoureux, University of Calgary, Seismic Imaging Summer School, August 7–11, 2006, Calgary.

^ Ch.: 9 Green's functions, p 6., J Peacock, FOURIER ANALYSIS LECTURE COURSE: LECTURE 15.

^ E. U. Condon, "Immersion of the Fourier transform in a continuous group of functional transformations", Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 23, (1937) 158–164. online

^ Wolfgang Pauli, Wave Mechanics: Volume 5 of Pauli Lectures on Physics (Dover Books on Physics, 2000) .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0486414620 , cf. Section 44.

^ Scharf, Günter. Finite Quantum Electrodynamics, The Casual Approach. Springer. p. 89. ISBN 978-3-642-63345-4.

^ Huang, p. 30

^ Greiner & Reinhardt 2008, Ch.2

^ "Graviton and gauge boson propagators in AdSd+1" (PDF).

^ abcd Bjorken and Drell, Appendix C

References

Bjorken, J.; Drell, S. (1965). Relativistic Quantum Fields. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-005494-0. (Appendix C.)

Bogoliubov, N.; Shirkov, D. V. Introduction to the theory of quantized fields. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 0-470-08613-0. (Especially pp. 136–156 and Appendix A)

DeWitt-Morette, C.; DeWitt, B. (eds.). Relativity, Groups and Topology. Glasgow: Blackie and Son. ISBN 0-444-86858-5. (section Dynamical Theory of Groups & Fields, Especially pp. 615–624)

Greiner, W.; Reinhardt, J. (2008). Quantum Electrodynamics (4th ed.). Springer Verlag. ISBN 9783540875604.

Greiner, W.; Reinhardt, J. (1996). Field Quantization. Springer Verlag. ISBN 9783540591795.

Griffiths, D. J. (1987). Introduction to Elementary Particles. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-60386-4.

Griffiths, D. J. (2004). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-131-11892-7.

Halliwell, J.J.; Orwitz, M., Sum-over-histories origin of the composition laws of relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum cosmology, arXiv:gr-qc/9211004, Bibcode:1993PhRvD..48..748H, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.48.748

Huang, Kerson (1998). Quantum Field Theory: From Operators to Path Integrals. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-14120-8.

Itzykson, C.; Zuber, J-B. (1980). Quantum Field Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-032071-3.

Pokorski, S. (1987). Gauge Field Theories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36846-4.

(Has useful appendices of Feynman diagram rules, including propagators, in the back.)

Schulman, L. S. (1981). Techniques & Applications of Path Integration. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-76450-7.

- Scharf, G. (1995). Finite Quantum Electrodynamics, The Casual Approach. Springer.

ISBN 978-3-642-63345-4.

External links

- Three Methods for Computing the Feynman Propagator

![{displaystyle K(x,t;x',t')=int exp left[{frac {i}{hbar }}int _{t}^{t'}L({dot {q}},q,t),dtright]D[q(t)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e955342647dcc12817f4053671bf1fce44f81416)

![{displaystyle G_{text{ret}}(x,y)=ilangle 0|left[Phi (x),Phi (y)right]|0rangle Theta (x^{0}-y^{0})}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/919d5e45fb1f438f28f4a192a3a521bd875ab1e0)

![left[Phi (x),Phi (y)right]:=Phi (x)Phi (y)-Phi (y)Phi (x)](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dd5c193518649d1efcc53776f9bf57231459b668)

![{displaystyle G_{text{adv}}(x,y)=-ilangle 0|left[Phi (x),Phi (y)right]|0rangle Theta (y^{0}-x^{0})~.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/52c088b6e64f0a02c16f81454d3e5b1c71956360)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}G_{F}(x-y)&=-ilangle 0|T(Phi (x)Phi (y))|0rangle \[4pt]&=-ileftlangle 0|left[Theta (x^{0}-y^{0})Phi (x)Phi (y)+Theta (y^{0}-x^{0})Phi (y)Phi (x)right]|0rightrangle .end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/464fd25d8ac399c3cdc9869a3ebb74e23bc6c607)

![{displaystyle S_{F}(x',x)=int {frac {d^{4}p}{(2pi )^{4}}}exp {left[-ipcdot (x'-x)right]}{tilde {S}}_{F}(p),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81a71c7f8b3f04f80e0b46f8ef96cc872982365b)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}&(inot nabla '-m)int {frac {d^{4}p}{(2pi )^{4}}}{tilde {S}}_{F}(p)exp {left[-ipcdot (x'-x)right]}\[6pt]={}&int {frac {d^{4}p}{(2pi )^{4}}}(not p-m){tilde {S}}_{F}(p)exp {left[-ipcdot (x'-x)right]}\[6pt]={}&int {frac {d^{4}p}{(2pi )^{4}}}I_{4}exp {left[-ipcdot (x'-x)right]}\[6pt]={}&I_{4}delta ^{4}(x'-x),end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4770a7ba0dbc05aa4f9d98e0faa34cb1b94c9a51)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}not pnot p&={frac {1}{2}}(not pnot p+not pnot p)\[6pt]&={frac {1}{2}}(gamma _{mu }p^{mu }gamma _{nu }p^{nu }+gamma _{nu }p^{nu }gamma _{mu }p^{mu })\[6pt]&={frac {1}{2}}(gamma _{mu }gamma _{nu }+gamma _{nu }gamma _{mu })p^{mu }p^{nu }\[6pt]&=g_{mu nu }p^{mu }p^{nu }=p_{nu }p^{nu }=p^{2},end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/05528a1d6393d467a6668bc427befaffebb1a630)

![{displaystyle langle 0|left[Phi (x),Phi (y)right]|0rangle =i,Delta (x-y)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ae71b05a978302792aa1c33fff1e4d96f5f2706b)