Louis Moreau Gottschalk

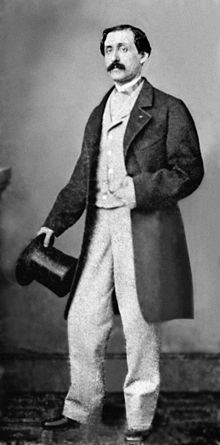

| Louis Gottschalk | |

|---|---|

Photograph by Mathew Brady (late 1850s-early 1860s) | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Louis Moreau Gottschalk |

| Born | (1829-05-08)May 8, 1829 New Orleans, Louisiana, United States |

| Died | December 18, 1869(1869-12-18) (aged 40) Rio de Janeiro, Empire of Brazil |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, pianist |

Louis Moreau Gottschalk (New Orleans, May 8, 1829 – Rio de Janeiro, December 18, 1869) was an American composer and pianist, best known as a virtuoso performer of his own romantic piano works.[1] He spent most of his working career outside of the United States.

Contents

1 Life and career

2 Works

3 Recordings

4 In popular culture

5 See also

6 References

6.1 Notes

6.2 Sources

7 External links

7.1 Listening

Life and career

Gottschalk was born in New Orleans to a Jewish businessman from London and a Creole mother. He had six brothers and sisters, five of whom were half-siblings by his father's biracial mistress.[2] His family lived for a time in a tiny cottage at Royal and Esplanade in the Vieux Carré. Louis later moved in with relatives at 518 Conti Street; his maternal grandmother Bruslé and his nurse Sally had both been born in Saint-Domingue (known later as Haiti). He was therefore exposed to a variety of musical traditions, and played the piano from an early age. He was soon recognized as a prodigy by the New Orleans bourgeois establishment, making his informal public debut in 1840 at the new St. Charles Hotel.

Only two years later, at the age of 13, Gottschalk left the United States and sailed to Europe, as he and his father realized a classical training was required to fulfill his musical ambitions. The Paris Conservatoire, however, rejected his application without hearing him, on the grounds of his nationality; Pierre Zimmerman, head of the piano faculty, commented that "America is a country of steam engines". Gottschalk eventually gained access to the musical establishment through family friends. After a concert at the Salle Pleyel, Frédéric Chopin remarked: "Give me your hand, my child; I predict that you will become the king of pianists." Franz Liszt and Charles-Valentin Alkan, too, recognised Gottschalk's extreme talent.[3]

After Gottschalk returned to the United States in 1853, he traveled extensively; a sojourn in Cuba during 1854 was the beginning of a series of trips to Central and South America.[4] Gottschalk also traveled to Puerto Rico after his Havana debut and at the start of his West Indian period. He was quite taken with the music he heard on the island, so much so that he composed a work, probably in 1857, entitled Souvenir de Porto Rico; Marche des gibaros, Op. 31 (RO250). "Gibaros" refers to the jíbaros, or Puerto Rican peasantry, and is an antiquated way of writing this name. The theme of the composition is a march tune which may be based on a Puerto Rican folk song form.[5]

At the conclusion of that tour, he rested in New Jersey then returned to New York City. There he continued to rest and took on a very young Venezuelan student by the name of Teresa Carreño. Gottschalk rarely took on students and was skeptical of prodigies, but Carreño was an exception and he was determined that she succeed. With his busy schedule, Gottschalk was only able to give her a handful of lessons, yet she would remember him fondly and performed his music for the rest of her days. A year after meeting Gottschalk, she performed for Abraham Lincoln and would go on to become a renowned concert pianist earning the nickname "Valkyrie of the Piano".

By the 1860s, Gottschalk had established himself as the best known pianist in the New World. Although born and reared in New Orleans, he was a supporter of the Union cause during the American Civil War. He returned to his native city only occasionally for concerts, but he always introduced himself as a New Orleans native.

In May 1865, he was mentioned in a San Francisco newspaper as having "travelled 95,000 miles by rail and given 1,000 concerts". However, he was forced to leave the United States later that year because of a scandalous affair with a student at the Oakland Female Seminary in Oakland, California. He never returned to the United States.

Gottschalk chose to travel to South America, where he continued to give frequent concerts. During one of these concerts, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on November 24, 1869, he collapsed from having contracted yellow fever.[6] Just before his collapse, he had finished playing his romantic piece Morte! (translated from Brazilian Portuguese as "Death"), although the actual collapse occurred just as he started to play his celebrated piece Tremolo. Gottschalk never recovered from the collapse.

Three weeks later, on December 18, 1869, at the age of 40, he died at his hotel in Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, probably from an overdose of quinine. (According to an essay by Jeremy Nicholas for the booklet accompanying the recording "Gottschalk Piano Music" performed by Philip Martin on the Hyperion label, "He died ... of empyema, the result of a ruptured abscess in the abdomen.")

In 1870, his remains were returned to the United States and were interred at the Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.[7] His burial spot was originally marked by a magnificent marble monument, topped by an "Angel of Music" statue, which was irreparably damaged by vandals in 1959.[8] In October 2012, after nearly fifteen years of fund raising by the Green-Wood Cemetery, a new "Angel of Music" statue, created by sculptors Giancarlo Biagi and Jill Burkee to replace the damaged one, was unveiled.[9]

His grand-nephew Louis Ferdinand Gottschalk was a notable composer of silent film and musical theatre scores. His nephew Alfred Louis Moreau Gottschalk was U.S Consul in Peru, Mexico, and Brazil in the early 20th Century and one of the passengers who perished in the disappearance of the USS Cyclops in 1918.

Works

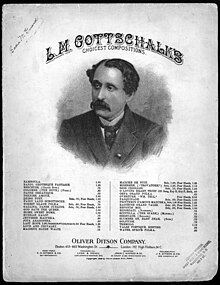

Louis Moreau Gottschalk pictured on an 1864 Publication of The Dying Poet for piano

Gottschalk's music was very popular during his lifetime and his earliest compositions created a sensation in Europe. Early pieces like Bamboula, La Savane, Le Bananier and Le Mancenillier were based on Gottschalk's memories of the music he heard during his youth in Louisiana. In this context, some of Gottschalk's work, such as the 13-minute opera Escenas campestres, retains a wonderfully innocent sweetness and charm. Gottschalk also utilized the Bamboula theme as a melody in his Symphony No. 1: A Night in the Tropics.

Many of his compositions were destroyed after his death, or are lost.

Recordings

Various pianists later recorded his piano music. The first important recordings of his orchestral music, including the symphony A Night in the Tropics, were made for Vanguard Records by Maurice Abravanel and the Utah Symphony Orchestra. Vox Records issued a multi-disc collection of his music, which was later reissued on CD. This included world premiere recordings of the original orchestrations of both symphonies and other works, which were conducted by Igor Buketoff and Samuel Adler. More recently, Philip Martin has recorded most of the extant piano music for Hyperion Records.

In popular culture

Author Howard Breslin wrote a historical novel about Gottschalk titled Concert Grand in 1963.[10]

See also

- Great Galloping Gottschalk

References

Notes

^ Louis Gottschalk: North American Theatre Online

^ Starr, S. Frederick, 1995. Bamboula! The life and times of Louis Moreau Gottschalk. Oxford, N.Y. pp. 22 et seq.

^ "Notes of a Pianist". Princeton University Press. Retrieved 22 April 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Louis Moreau Gottschalk Biography".

^ Louis Moreau Gottschalk Piano Music. Edward Gold, piano (Bösendorfer). Liner notes by Edward Gold. The Musical Heritage Society Inc. MHS 1629.

^ "Louis Moreau Gottschalk Facts". yourdictionary.com. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 18177-18178). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

^ Barron, James. "A Brooklyn Mystery Solved: Vandals Did It, in 1959".

^ "Welcome, "Angel of Music" – Green-Wood". green-wood.com. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

^ Library Journal, 88 (4), 1963, p. 3691

Sources

- Irving Lowens/S. Frederick Starr: "Louis Moreau Gottschalk", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed June 28, 2007), (subscription access)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louis Moreau Gottschalk. |

Wikisource has original works written by or about: Louis Moreau Gottschalk |

Wikisource has the text of a 1900 Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography article about Louis Moreau Gottschalk. |

- Louis Moreau Gottschalk, pianiste itinérant (French dedicated website with scores and audio extracts)

- English Works List on French dedicated site

- Louis Moreau Gottschalk, a dedicated website

- Louis Moreau Gottschalk: Pioneering Pianist/Composer of the Americas (Catalogue of works, links to reference information)

Louis Moreau Gottschalk at Find a Grave

Biographical sketch at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2009-07-18)

Adam Kirsch, "Diary of a 'One-Man Grateful Dead'", The New York Sun, June 7, 2006.

Free scores by Louis Moreau Gottschalk at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

Free scores at the Mutopia Project

Listening

Art of the States: Louis Moreau Gottschalk (six works by the composer) at the Wayback Machine (archived 2005-10-22)

"Creole Eyes" a.k.a. "Dance Cubaine", Op. 37 on YouTube

- Kunst der Fuge: Louis Moreau Gottschalk – MIDI files (piano works)