Egyptian cigarette industry

A nineteenth-century, tin box of Kyriazi Frères brand, Egyptian cigarettes

The Egyptian cigarette industry, during the period between the 1880s and the end of the First World War, was a major export industry that influenced global fashion. It was notable as a rare example of the global periphery setting trends in the global center in a period when the predominant direction of cultural influence was the reverse, and also as one of the earliest producers of globally traded manufactured finished goods outside the West.

Contents

1 Rise

2 Decline

3 In culture

4 See also

5 Notes and references

6 Sources and bibliography

Rise

The development of a major cigarette industry in Egypt in the late nineteenth century was unexpected, given that Egypt generally exported raw materials and imported manufactured goods, that Egyptian-grown tobacco was always of poor quality, and that the cultivation of tobacco in Egypt was banned in 1890 (a measure intended to facilitate the collection of taxes on tobacco).

One reason for the development of the industry was the imposition of a state tobacco monopoly in the Ottoman Empire, a measure designed to increase Ottoman government revenue. This resulted in the movement of many Ottoman tobacco merchants, usually ethnic Greeks, to Egypt, a country which was culturally similar to and was in fact arguably de jure a part of the Ottoman Empire but outside the tobacco monopoly as a result of its de facto occupation by the United Kingdom.

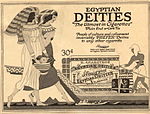

A 1919 American advertisement for an Egypt–inspired cigarette brand, S. Anargyros' "Egyptian deities"

The founder of the industry was Nestor Gianaclis, a Greek who arrived in Egypt in 1864 and in 1871 established a factory in the Khairy Pasha palace in Cairo.[Note 1] After British troops began being stationed in Egypt in 1882, British officers developed a taste for the Egyptian cigarettes and they were soon being exported to the United Kingdom.[1] Gianaclis and other Greek industrialists such as Ioannis Kyriazis of Kyriazi frères successfully produced and exported cigarettes using imported Turkish tobacco to meet the growing world demand for cigarettes in the closing decades of the nineteenth century.[2]

Egyptian cigarettes made by Gianaclis and others became so popular in Europe and the United States that they inspired a large number of what were, in effect, locally produced counterfeits. Among these was the American Camel brand, established in 1913, which used on its packet three Egyptian motifs: the camel, the pyramids, and a palm tree. Fellow Greeks in the United States also imported or produced such cigarettes. For example, S. Anargyros first imported Egyptian Deities and then produced Murad, Helmar and Mogul, and the Stephano Brothers produced Ramses II.[3]

| 1897 | 1899 | 1901 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | kg | cigarettes | kg | cigarettes | kg | cigarettes |

| Kyriazi Frères | 76,386 | 51,726,550 | 120,987 | 89,414,500 | 140,654 | 108,174,225 |

| Nestor Gianaclis | 37,178 | 30,537,110 | 55,203 | 48,025,660 | 70,680 | 56,000,000 |

| Dimitrino et Co. | 24,569 | 18,564,135 | 27,916 | 21,982,380 | 30,980 | 26,000,000 |

| Th. Vafiadis et Co. | 21,568 | 14,033,900 | 23,861 | 16,330,060 | 32,067 | 23,000,000 |

| M. Melachrino et Co. | 17,920 | 12,096,340 | 20,782 | 13,936,626 | 60,237 | 46,000,000 |

| Nicolas Soussa Frères | - | - | - | - | 29,260 | 24,000,000 |

| Others | 47,952 | 33,583,909 | 59,224 | 43,636,800 | 70,982 | 64,313,976 |

| Totals | 225,573 | 160,541,944 | 307,973 | 233,326,026 | 434,860 | 347,288,201 |

Decline

Tastes in Europe and the United States shifted away from Turkish tobacco and Egyptian cigarettes towards Virginia tobacco, during and after the First World War. What remained of the Greek-run tobacco industry in Egypt was nationalized after the Egyptian Revolution of 1952. Egyptian-made cigarettes were thereafter sold only domestically, and became known for their poor quality (and low price).

Cigarettes containing Turkish tobacco (which includes those varieties grown in what is now Greece) exclusively continued to be manufactured and sold as "Turkish cigarettes" in the US (brands Murad, Helmar and others), the UK (Sullivan & Powell, Benson & Hedges, Fribourg & Treyer, Balkan Sobranie) and Germany (where the so-called "Orientzigaretten" had the major market share before the Second World War). Today, Turkish tobacco is a key ingredient in American blend cigarettes (Virginia, Burley, Turkish) introduced with Camels in 1913.

In culture

Arthur Conan Doyle paid a casual tribute to the popularity of Egyptian cigarettes in his 1904 story "The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez", where a character interviewed by Sherlock Holmes in a murder investigation is described as a very heavy consumer of them.

- "A smoker, Mr. Holmes?" said he, speaking in well-chosen English, with a curious little mincing accent. "Pray take a cigarette. And you, sir? I can recommend them, for I have them especially prepared by Ionides, of Alexandria. He sends me a thousand at a time, and I grieve to say that I have to arrange for a fresh supply every fortnight.

His copious cigarette ash eventually helps Holmes solve the mystery.

Egyptian cigarette advertisements are parodied in Hergé's graphic novel Cigars of the Pharaoh. Tintin has a nightmare where characters in ancient Egyptian garb smoke opium-laced cigars.

A Kyriazi Frères tin box appears in the 2017 movie Blade Runner 2049.

See also

- Kyriazi freres

Notes and references

- Notes

^ After Gianaclis moved to larger premises in 1907, this became the home first of Cairo University and then of the American University in Cairo.

- References

^ Cox (2000), p.47

^ Politis, Athanase (1929). L'Hellénisme et l'Egypte moderne. Librairie Félix Alcan. p. 572..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Brier, Bob (2013). Egyptomania: Our Three Thousand Year Obsession with the Land of the Pharaohs. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-27860-9. At Google Books.

^ Shechter, Relli (2006). Smoking, Culture and Economy in the Middle East: The Egyptian Tobacco Market 1850-2000. I.B.Tauris. p. 39. ISBN 1-84511-137-0. At Google Books.

Sources and bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Shechter, Relli (February 2003). "Selling Luxury: The Rise of the Egyptian Cigarette and the Transformation of the Egyptian Tobacco Market, 1850-1914". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 35 (1): 51–75. doi:10.1017/s0020743803000035. JSTOR 3879927.

Cox, Howard (2000). The Global Cigarette: Origin and Evolution of British American Tobacco, 1880-1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019829221X.