British Empire

British Empire | |

|---|---|

Flag of the United Kingdom | |

All areas of the world that were ever part of the British Empire. Current British Overseas Territories have their names underlined in red. |

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It originated with the overseas possessions and trading posts established by England between the late 16th and early 18th centuries. At its height, it was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power.[1] By 1913, the British Empire held sway over 412 million people, 7001230000000000000♠23% of the world population at the time,[2] and by 1920, it covered 35,500,000 km2 (13,700,000 sq mi),[3]7001240000000000000♠24% of the Earth's total land area.[4] As a result, its political, legal, linguistic and cultural legacy is widespread. At the peak of its power, the phrase "the empire on which the sun never sets" was often used to describe the British Empire, because its expanse around the globe meant that the sun was always shining on at least one of its territories.[5]

During the Age of Discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries, Portugal and Spain pioneered European exploration of the globe, and in the process established large overseas empires. Envious of the great wealth these empires generated,[6] England, France, and the Netherlands began to establish colonies and trade networks of their own in the Americas and Asia.[7] A series of wars in the 17th and 18th centuries with the Netherlands and France left England and then, following union between England and Scotland in 1707, Great Britain, the dominant colonial power in North America. It then became the dominant power in the Indian subcontinent after the East India Company's conquest of Mughal Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757.

The independence of the Thirteen Colonies in North America in 1783 after the American War of Independence caused Britain to lose some of its oldest and most populous colonies. British attention soon turned towards Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. After the defeat of France in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815), Britain emerged as the principal naval and imperial power of the 19th century.[8]Unchallenged at sea, British dominance was later described as Pax Britannica ("British Peace"), a period of relative peace in Europe and the world (1815–1914) during which the British Empire became the global hegemon and adopted the role of global policeman.[9][10][11] In the early 19th century, the Industrial Revolution began to transform Britain; so that by the time of the Great Exhibition in 1851, the country was described as the "workshop of the world".[12] The British Empire expanded to include most of India, large parts of Africa and many other territories throughout the world. Alongside the formal control that Britain exerted over its own colonies, its dominance of much of world trade meant that it effectively controlled the economies of many regions, such as Asia and Latin America.[13][14]

During the 19th century, Britain's population increased at a dramatic rate, accompanied by rapid urbanisation, which caused significant social and economic stresses.[15] To seek new markets and sources of raw materials, the British government under Benjamin Disraeli initiated a period of imperial expansion in Egypt, South Africa, and elsewhere. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand became self-governing dominions.[16]

By the start of the 20th century, Germany and the United States had begun to challenge Britain's economic lead. Subsequent military and economic tensions between Britain and Germany were major causes of the First World War, during which Britain relied heavily upon its empire. The conflict placed enormous strain on the military, financial and manpower resources of Britain. Although the British Empire achieved its largest territorial extent immediately after World War I, Britain was no longer the world's pre-eminent industrial or military power. In the Second World War, Britain's colonies in East and Southeast Asia were occupied by Japan. Despite the final victory of Britain and its allies, the damage to British prestige helped to accelerate the decline of the empire. India, Britain's most valuable and populous possession, achieved independence as part of a larger decolonisation movement in which Britain granted independence to most territories of the empire. The transfer of Hong Kong to China in 1997 marked for many the end of the British Empire.[17][18][19][20] Fourteen overseas territories remain under British sovereignty.

After independence, many former British colonies joined the Commonwealth of Nations, a free association of independent states. The United Kingdom is now one of 16 Commonwealth nations, a grouping known informally as the Commonwealth realms, that share a monarch, Queen Elizabeth II.

Contents

1 Origins (1497–1583)

1.1 Plantations of Ireland

2 "First" British Empire (1583–1783)

2.1 Americas, Africa and the slave trade

2.2 Rivalry with the Netherlands in Asia

2.3 Global conflicts with France

2.4 Loss of the Thirteen American Colonies

3 Rise of the "Second" British Empire (1783–1815)

3.1 Exploration of the Pacific

3.2 War with Napoleonic France

3.3 Abolition of slavery

4 Britain's imperial century (1815–1914)

4.1 East India Company in Asia

4.2 Rivalry with Russia

4.3 Cape to Cairo

4.4 Changing status of the white colonies

5 World wars (1914–1945)

5.1 First World War

5.2 Inter-war period

5.3 Second World War

6 Decolonisation and decline (1945–1997)

6.1 Initial disengagement

6.2 Suez and its aftermath

6.3 Wind of change

6.4 End of empire

7 Legacy

8 See also

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

Origins (1497–1583)

A replica of the Matthew, John Cabot's ship used for his second voyage to the New World

The foundations of the British Empire were laid when England and Scotland were separate kingdoms. In 1496, King Henry VII of England, following the successes of Spain and Portugal in overseas exploration, commissioned John Cabot to lead a voyage to discover a route to Asia via the North Atlantic.[7] Cabot sailed in 1497, five years after the European discovery of America, but he made landfall on the coast of Newfoundland, and, mistakenly believing (like Christopher Columbus) that he had reached Asia,[21] there was no attempt to found a colony. Cabot led another voyage to the Americas the following year but nothing was ever heard of his ships again.[22]

No further attempts to establish English colonies in the Americas were made until well into the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, during the last decades of the 16th century.[23] In the meantime, the 1533 Statute in Restraint of Appeals had declared "that this realm of England is an Empire".[24] The subsequent Protestant Reformation turned England and Catholic Spain into implacable enemies.[7] In 1562, the English Crown encouraged the privateers John Hawkins and Francis Drake to engage in slave-raiding attacks against Spanish and Portuguese ships off the coast of West Africa[25] with the aim of breaking into the Atlantic slave trade. This effort was rebuffed and later, as the Anglo-Spanish Wars intensified, Elizabeth I gave her blessing to further privateering raids against Spanish ports in the Americas and shipping that was returning across the Atlantic, laden with treasure from the New World.[26] At the same time, influential writers such as Richard Hakluyt and John Dee (who was the first to use the term "British Empire")[27] were beginning to press for the establishment of England's own empire. By this time, Spain had become the dominant power in the Americas and was exploring the Pacific Ocean, Portugal had established trading posts and forts from the coasts of Africa and Brazil to China, and France had begun to settle the Saint Lawrence River area, later to become New France.[28]

Plantations of Ireland

Although England trailed behind other European powers in establishing overseas colonies, it had been engaged during the 16th century in the settlement of Ireland with Protestants from England and Scotland, drawing on precedents dating back to the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169.[29][30] Several people who helped establish the Plantations of Ireland also played a part in the early colonisation of North America, particularly a group known as the West Country men.[31]

"First" British Empire (1583–1783)

In 1578, Elizabeth I granted a patent to Humphrey Gilbert for discovery and overseas exploration.[32] That year, Gilbert sailed for the Caribbean with the intention of engaging in piracy and establishing a colony in North America, but the expedition was aborted before it had crossed the Atlantic.[33][34] In 1583, he embarked on a second attempt, on this occasion to the island of Newfoundland whose harbour he formally claimed for England, although no settlers were left behind. Gilbert did not survive the return journey to England, and was succeeded by his half-brother, Walter Raleigh, who was granted his own patent by Elizabeth in 1584. Later that year, Raleigh founded the Roanoke Colony on the coast of present-day North Carolina, but lack of supplies caused the colony to fail.[35]

In 1603, James VI, King of Scots, ascended (as James I) to the English throne and in 1604 negotiated the Treaty of London, ending hostilities with Spain. Now at peace with its main rival, English attention shifted from preying on other nations' colonial infrastructures to the business of establishing its own overseas colonies.[36] The British Empire began to take shape during the early 17th century, with the English settlement of North America and the smaller islands of the Caribbean, and the establishment of joint-stock companies, most notably the East India Company, to administer colonies and overseas trade. This period, until the loss of the Thirteen Colonies after the American War of Independence towards the end of the 18th century, has subsequently been referred to by some historians as the "First British Empire".[37]

Americas, Africa and the slave trade

The Caribbean initially provided England's most important and lucrative colonies,[38] but not before several attempts at colonisation failed. An attempt to establish a colony in Guiana in 1604 lasted only two years, and failed in its main objective to find gold deposits.[39] Colonies in St Lucia (1605) and Grenada (1609) also rapidly folded, but settlements were successfully established in St. Kitts (1624), Barbados (1627) and Nevis (1628).[40] The colonies soon adopted the system of sugar plantations successfully used by the Portuguese in Brazil, which depended on slave labour, and—at first—Dutch ships, to sell the slaves and buy the sugar.[41] To ensure that the increasingly healthy profits of this trade remained in English hands, Parliament decreed in 1651 that only English ships would be able to ply their trade in English colonies. This led to hostilities with the United Dutch Provinces—a series of Anglo-Dutch Wars—which would eventually strengthen England's position in the Americas at the expense of the Dutch.[42] In 1655, England annexed the island of Jamaica from the Spanish, and in 1666 succeeded in colonising the Bahamas.[43]

British colonies in North America, 1763–1776

England's first permanent settlement in the Americas was founded in 1607 in Jamestown, led by Captain John Smith and managed by the Virginia Company. Bermuda was settled and claimed by England as a result of the 1609 shipwreck of the Virginia Company's flagship, and in 1615 was turned over to the newly formed Somers Isles Company.[44] The Virginia Company's charter was revoked in 1624 and direct control of Virginia was assumed by the crown, thereby founding the Colony of Virginia.[45] The London and Bristol Company was created in 1610 with the aim of creating a permanent settlement on Newfoundland, but was largely unsuccessful.[46] In 1620, Plymouth was founded as a haven for Puritan religious separatists, later known as the Pilgrims.[47] Fleeing from religious persecution would become the motive of many English would-be colonists to risk the arduous trans-Atlantic voyage: Maryland was founded as a haven for Roman Catholics (1634), Rhode Island (1636) as a colony tolerant of all religions and Connecticut (1639) for Congregationalists. The Province of Carolina was founded in 1663. With the surrender of Fort Amsterdam in 1664, England gained control of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, renaming it New York. This was formalised in negotiations following the Second Anglo-Dutch War, in exchange for Suriname.[48] In 1681, the colony of Pennsylvania was founded by William Penn. The American colonies were less financially successful than those of the Caribbean, but had large areas of good agricultural land and attracted far larger numbers of English emigrants who preferred their temperate climates.[49]

African slaves working in 17th-century Virginia, by an unknown artist, 1670

In 1670, Charles II incorporated by royal charter the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), granting it a monopoly on the fur trade in the area known as Rupert's Land, which would later form a large proportion of the Dominion of Canada. Forts and trading posts established by the HBC were frequently the subject of attacks by the French, who had established their own fur trading colony in adjacent New France.[50]

Two years later, the Royal African Company was inaugurated, receiving from King Charles a monopoly of the trade to supply slaves to the British colonies of the Caribbean.[51] From the outset, slavery was the basis of the British Empire in the West Indies. Until the abolition of its slave trade in 1807, Britain was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic.[52] To facilitate this trade, forts were established on the coast of West Africa, such as James Island, Accra and Bunce Island. In the British Caribbean, the percentage of the population of African descent rose from 25% in 1650 to around 80% in 1780, and in the Thirteen Colonies from 10% to 40% over the same period (the majority in the southern colonies).[53] For the slave traders, the trade was extremely profitable, and became a major economic mainstay for such western British cities as Bristol and Liverpool, which formed the third corner of the triangular trade with Africa and the Americas. For the transported, harsh and unhygienic conditions on the slaving ships and poor diets meant that the average mortality rate during the Middle Passage was one in seven.[54]

In 1695, the Parliament of Scotland granted a charter to the Company of Scotland, which established a settlement in 1698 on the Isthmus of Panama. Besieged by neighbouring Spanish colonists of New Granada, and afflicted by malaria, the colony was abandoned two years later. The Darien scheme was a financial disaster for Scotland—a quarter of Scottish capital[55] was lost in the enterprise—and ended Scottish hopes of establishing its own overseas empire. The episode also had major political consequences, persuading the governments of both England and Scotland of the merits of a union of countries, rather than just crowns.[56] This occurred in 1707 with the Treaty of Union, establishing the Kingdom of Great Britain.

Rivalry with the Netherlands in Asia

Fort St. George was founded at Madras in 1639.

At the end of the 16th century, England and the Netherlands began to challenge Portugal's monopoly of trade with Asia, forming private joint-stock companies to finance the voyages—the English, later British, East India Company and the Dutch East India Company, chartered in 1600 and 1602 respectively. The primary aim of these companies was to tap into the lucrative spice trade, an effort focused mainly on two regions; the East Indies archipelago, and an important hub in the trade network, India. There, they competed for trade supremacy with Portugal and with each other.[57] Although England ultimately eclipsed the Netherlands as a colonial power, in the short term the Netherlands' more advanced financial system[58] and the three Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th century left it with a stronger position in Asia. Hostilities ceased after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when the Dutch William of Orange ascended the English throne, bringing peace between the Netherlands and England. A deal between the two nations left the spice trade of the East Indies archipelago to the Netherlands and the textiles industry of India to England, but textiles soon overtook spices in terms of profitability, and by 1720, in terms of sales, the British company had overtaken the Dutch.[58]

Global conflicts with France

The death of British General James Wolfe at the 1759 Battle of Quebec during the French and Indian War

Peace between England and the Netherlands in 1688 meant that the two countries entered the Nine Years' War as allies, but the conflict—waged in Europe and overseas between France, Spain and the Anglo-Dutch alliance—left the English a stronger colonial power than the Dutch, who were forced to devote a larger proportion of their military budget on the costly land war in Europe.[59] The 18th century saw England (after 1707, Britain) rise to be the world's dominant colonial power, and France becoming its main rival on the imperial stage.[60]

The death of Charles II of Spain in 1700 and his bequeathal of Spain and its colonial empire to Philippe of Anjou, a grandson of the King of France, raised the prospect of the unification of France, Spain and their respective colonies, an unacceptable state of affairs for England and the other powers of Europe.[61] In 1701, England, Portugal and the Netherlands sided with the Holy Roman Empire against Spain and France in the War of the Spanish Succession, which lasted until 1714.

At the concluding Treaty of Utrecht, Philip renounced his and his descendants' right to the French throne and Spain lost its empire in Europe.[61] The British Empire was territorially enlarged: from France, Britain gained Newfoundland and Acadia, and from Spain, Gibraltar and Menorca. Gibraltar became a critical naval base and allowed Britain to control the Atlantic entry and exit point to the Mediterranean. Spain also ceded the rights to the lucrative asiento (permission to sell slaves in Spanish America) to Britain.[62]

Robert Clive's victory at the Battle of Plassey established the East India Company as a military as well as a commercial power.

During the middle decades of the 18th century, there were several outbreaks of military conflict on the Indian subcontinent, the Carnatic Wars, as the English East India Company (often known simply as "the Company") and its French counterpart, the French East India Company (Compagnie française des Indes orientales), struggled alongside local rulers to fill the vacuum that had been left by the decline of the Mughal Empire. The Battle of Plassey in 1757, in which the British, led by Robert Clive, defeated the Nawab of Bengal and his French allies, left the British East India Company in control of Bengal and as the major military and political power in India.[63] France was left control of its enclaves but with military restrictions and an obligation to support British client states, ending French hopes of controlling India.[64] In the following decades the British East India Company gradually increased the size of the territories under its control, either ruling directly or via local rulers under the threat of force from the British Indian Army, the vast majority of which was composed of Indian sepoys.[65]

The British and French struggles in India became but one theatre of the global Seven Years' War (1756–1763) involving France, Britain and the other major European powers. The signing of the Treaty of Paris (1763) had important consequences for the future of the British Empire. In North America, France's future as a colonial power effectively ended with the recognition of British claims to Rupert's Land,[50] and the ceding of New France to Britain (leaving a sizeable French-speaking population under British control) and Louisiana to Spain. Spain ceded Florida to Britain. Along with its victory over France in India, the Seven Years' War therefore left Britain as the world's most powerful maritime power.[66]

Loss of the Thirteen American Colonies

During the 1760s and early 1770s, relations between the Thirteen Colonies and Britain became increasingly strained, primarily because of resentment of the British Parliament's attempts to govern and tax American colonists without their consent.[67] This was summarised at the time by the slogan "No taxation without representation", a perceived violation of the guaranteed Rights of Englishmen. The American Revolution began with rejection of Parliamentary authority and moves towards self-government. In response, Britain sent troops to reimpose direct rule, leading to the outbreak of war in 1775. The following year, in 1776, the United States declared independence. The entry of France into the war in 1778 tipped the military balance in the Americans' favour and after a decisive defeat at Yorktown in 1781, Britain began negotiating peace terms. American independence was acknowledged at the Peace of Paris in 1783.[68]

Surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown. The loss of the American colonies marked the end of the "first British Empire".

The loss of such a large portion of British America, at the time Britain's most populous overseas possession, is seen by some historians as the event defining the transition between the "first" and "second" empires,[69] in which Britain shifted its attention away from the Americas to Asia, the Pacific and later Africa. Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, had argued that colonies were redundant, and that free trade should replace the old mercantilist policies that had characterised the first period of colonial expansion, dating back to the protectionism of Spain and Portugal.[66][70] The growth of trade between the newly independent United States and Britain after 1783 seemed to confirm Smith's view that political control was not necessary for economic success.[71][72]

The war to the south influenced British policy in Canada, where between 40,000 and 100,000[73] defeated Loyalists had migrated from the new United States following independence.[74] The 14,000 Loyalists who went to the Saint John and Saint Croix river valleys, then part of Nova Scotia, felt too far removed from the provincial government in Halifax, so London split off New Brunswick as a separate colony in 1784.[75] The Constitutional Act of 1791 created the provinces of Upper Canada (mainly English-speaking) and Lower Canada (mainly French-speaking) to defuse tensions between the French and British communities, and implemented governmental systems similar to those employed in Britain, with the intention of asserting imperial authority and not allowing the sort of popular control of government that was perceived to have led to the American Revolution.[76]

Tensions between Britain and the United States escalated again during the Napoleonic Wars, as Britain tried to cut off American trade with France and boarded American ships to impress men into the Royal Navy. The US declared war, the War of 1812, and invaded Canadian territory. In response Britain invaded the US, but the pre-war boundaries were reaffirmed by the 1814 Treaty of Ghent, ensuring Canada's future would be separate from that of the United States.[77][78]

Rise of the "Second" British Empire (1783–1815)

Exploration of the Pacific

James Cook's mission was to find the alleged southern continent Terra Australis.

Since 1718, transportation to the American colonies had been a penalty for various offences in Britain, with approximately one thousand convicts transported per year across the Atlantic.[79] Forced to find an alternative location after the loss of the Thirteen Colonies in 1783, the British government turned to the newly discovered lands of Australia.[80] The coast of Australia had been discovered for Europeans by the Dutch explorer Willem Janszoon in 1606 and was named New Holland by the Dutch East India Company,[81] but there was no attempt to colonise it. In 1770 James Cook discovered the eastern coast of Australia while on a scientific voyage to the South Pacific Ocean, claimed the continent for Britain, and named it New South Wales.[82] In 1778, Joseph Banks, Cook's botanist on the voyage, presented evidence to the government on the suitability of Botany Bay for the establishment of a penal settlement, and in 1787 the first shipment of convicts set sail, arriving in 1788.[83] Britain continued to transport convicts to New South Wales until 1840, to Tasmania until 1853 and to Western Australia until 1868.[84] The Australian colonies became profitable exporters of wool and gold,[85] mainly because of gold rushes in the colony of Victoria, making its capital Melbourne for a time the richest city in the world[86] and the second largest city (after London) in the British Empire.[87]

During his voyage, Cook also visited New Zealand, first discovered by Dutch explorer Abel Tasman in 1642, and claimed the North and South islands for the British crown in 1769 and 1770 respectively. Initially, interaction between the indigenous Māori population and Europeans was limited to the trading of goods. European settlement increased through the early decades of the 19th century, with numerous trading stations established, especially in the North. In 1839, the New Zealand Company announced plans to buy large tracts of land and establish colonies in New Zealand. On 6 February 1840, Captain William Hobson and around 40 Maori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi.[88] This treaty is considered by many to be New Zealand's founding document,[89] but differing interpretations of the Maori and English versions of the text[90] have meant that it continues to be a source of dispute.[91]

War with Napoleonic France

Britain was challenged again by France under Napoleon, in a struggle that, unlike previous wars, represented a contest of ideologies between the two nations.[92] It was not only Britain's position on the world stage that was at risk: Napoleon threatened to invade Britain itself, just as his armies had overrun many countries of continental Europe.

The Battle of Waterloo ended in the defeat of Napoleon.

The Napoleonic Wars were therefore ones in which Britain invested large amounts of capital and resources to win. French ports were blockaded by the Royal Navy, which won a decisive victory over a Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar in 1805. Overseas colonies were attacked and occupied, including those of the Netherlands, which was annexed by Napoleon in 1810. France was finally defeated by a coalition of European armies in 1815.[93] Britain was again the beneficiary of peace treaties: France ceded the Ionian Islands, Malta (which it had occupied in 1797 and 1798 respectively), Mauritius, Saint Lucia, and Tobago; Spain ceded Trinidad; the Netherlands Guyana, and the Cape Colony. Britain returned Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana, and Réunion to France, and Java and Suriname to the Netherlands, while gaining control of Ceylon (1795–1815).[94]

Abolition of slavery

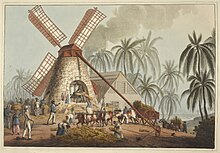

Sugar plantation in the British colony of Antigua, 1823

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, goods produced by slavery became less important to the British economy.[95] Added to this was the cost of suppressing regular slave rebellions. With support from the British abolitionist movement, Parliament enacted the Slave Trade Act in 1807, which abolished the slave trade in the empire. In 1808, Sierra Leone Colony and Protectorate was designated an official British colony for freed slaves.[96] Parliamentary reform in 1832 saw the influence of the West India Committee decline. The Slavery Abolition Act, passed the following year, abolished slavery in the British Empire on 1 August 1834, finally bringing the Empire into line with the law in the UK (with the exception of St. Helena, Ceylon and the territories administered by the East India Company, though these exclusions were later repealed). Under the Act, slaves were granted full emancipation after a period of four to six years of "apprenticeship".[97] The British government compensated slave-owners.

Britain's imperial century (1815–1914)

An elaborate map of the British Empire in 1910, marked in the traditional colour for imperial British dominions on maps

Between 1815 and 1914, a period referred to as Britain's "imperial century" by some historians,[98][99] around 10,000,000 square miles (26,000,000 km2) of territory and roughly 400 million people were added to the British Empire.[100] Victory over Napoleon left Britain without any serious international rival, other than Russia in Central Asia.[101] Unchallenged at sea, Britain adopted the role of global policeman, a state of affairs later known as the Pax Britannica,[10] and a foreign policy of "splendid isolation".[102] Alongside the formal control it exerted over its own colonies, Britain's dominant position in world trade meant that it effectively controlled the economies of many countries, such as China, Argentina and Siam, which has been described by some historians as an "Informal Empire".[13][103]

British imperial strength was underpinned by the steamship and the telegraph, new technologies invented in the second half of the 19th century, allowing it to control and defend the empire. By 1902, the British Empire was linked together by a network of telegraph cables, called the All Red Line.[104]

East India Company in Asia

An 1876 political cartoon of Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881) making Queen Victoria Empress of India. The caption reads "New crowns for old ones!"

The East India Company drove the expansion of the British Empire in Asia. The Company's army had first joined forces with the Royal Navy during the Seven Years' War, and the two continued to co-operate in arenas outside India: the eviction of the French from Egypt (1799),[105] the capture of Java from the Netherlands (1811), the acquisition of Penang Island (1786), Singapore (1819) and Malacca (1824), and the defeat of Burma (1826).[101]

From its base in India, the Company had also been engaged in an increasingly profitable opium export trade to China since the 1730s. This trade, illegal since it was outlawed by the Qing dynasty in 1729, helped reverse the trade imbalances resulting from the British imports of tea, which saw large outflows of silver from Britain to China.[106] In 1839, the confiscation by the Chinese authorities at Canton of 20,000 chests of opium led Britain to attack China in the First Opium War, and resulted in the seizure by Britain of Hong Kong Island, at that time a minor settlement.[107]

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries the British Crown began to assume an increasingly large role in the affairs of the Company. A series of Acts of Parliament were passed, including the Regulating Act of 1773, Pitt's India Act of 1784 and the Charter Act of 1813 which regulated the Company's affairs and established the sovereignty of the Crown over the territories that it had acquired.[108] The Company's eventual end was precipitated by the Indian Rebellion in 1857, a conflict that had begun with the mutiny of sepoys, Indian troops under British officers and discipline.[109] The rebellion took six months to suppress, with heavy loss of life on both sides. The following year the British government dissolved the Company and assumed direct control over India through the Government of India Act 1858, establishing the British Raj, where an appointed governor-general administered India and Queen Victoria was crowned the Empress of India.[110] India became the empire's most valuable possession, "the Jewel in the Crown", and was the most important source of Britain's strength.[111]

A series of serious crop failures in the late 19th century led to widespread famines on the subcontinent in which it is estimated that over 15 million people died. The East India Company had failed to implement any coordinated policy to deal with the famines during its period of rule. Later, under direct British rule, commissions were set up after each famine to investigate the causes and implement new policies, which took until the early 1900s to have an effect.[112]

Rivalry with Russia

British cavalry charging against Russian forces at Balaclava in 1854

During the 19th century, Britain and the Russian Empire vied to fill the power vacuums that had been left by the declining Ottoman Empire, Qajar dynasty and Qing Dynasty. This rivalry in Central Asia came to be known as the "Great Game".[113] As far as Britain was concerned, defeats inflicted by Russia on Persia and Turkey demonstrated its imperial ambitions and capabilities and stoked fears in Britain of an overland invasion of India.[114] In 1839, Britain moved to pre-empt this by invading Afghanistan, but the First Anglo-Afghan War was a disaster for Britain.[115]

When Russia invaded the Turkish Balkans in 1853, fears of Russian dominance in the Mediterranean and Middle East led Britain and France to invade the Crimean Peninsula to destroy Russian naval capabilities.[115] The ensuing Crimean War (1854–56), which involved new techniques of modern warfare,[116] was the only global war fought between Britain and another imperial power during the Pax Britannica and was a resounding defeat for Russia.[115] The situation remained unresolved in Central Asia for two more decades, with Britain annexing Baluchistan in 1876 and Russia annexing Kirghizia, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. For a while it appeared that another war would be inevitable, but the two countries reached an agreement on their respective spheres of influence in the region in 1878 and on all outstanding matters in 1907 with the signing of the Anglo-Russian Entente.[117] The destruction of the Russian Navy by the Japanese at the Battle of Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 also limited its threat to the British.[118]

Cape to Cairo

The Rhodes Colossus—Cecil Rhodes spanning "Cape to Cairo"

The Dutch East India Company had founded the Cape Colony on the southern tip of Africa in 1652 as a way station for its ships travelling to and from its colonies in the East Indies. Britain formally acquired the colony, and its large Afrikaner (or Boer) population in 1806, having occupied it in 1795 to prevent its falling into French hands during the Flanders Campaign.[119] British immigration began to rise after 1820, and pushed thousands of Boers, resentful of British rule, northwards to found their own—mostly short-lived—independent republics, during the Great Trek of the late 1830s and early 1840s.[120] In the process the Voortrekkers clashed repeatedly with the British, who had their own agenda with regard to colonial expansion in South Africa and to the various native African polities, including those of the Sotho and the Zulu nations. Eventually the Boers established two republics which had a longer lifespan: the South African Republic or Transvaal Republic (1852–77; 1881–1902) and the Orange Free State (1854–1902).[121] In 1902 Britain occupied both republics, concluding a treaty with the two Boer Republics following the Second Boer War (1899–1902).[122]

In 1869 the Suez Canal opened under Napoleon III, linking the Mediterranean with the Indian Ocean. Initially the Canal was opposed by the British;[123] but once opened, its strategic value was quickly recognised and became the "jugular vein of the Empire".[124] In 1875, the Conservative government of Benjamin Disraeli bought the indebted Egyptian ruler Isma'il Pasha's 44% shareholding in the Suez Canal for £4 million (equivalent to £350 million in 2016). Although this did not grant outright control of the strategic waterway, it did give Britain leverage. Joint Anglo-French financial control over Egypt ended in outright British occupation in 1882.[125] The French were still majority shareholders and attempted to weaken the British position,[126] but a compromise was reached with the 1888 Convention of Constantinople, which made the Canal officially neutral territory.[127]

With competitive French, Belgian and Portuguese activity in the lower Congo River region undermining orderly colonisation of tropical Africa, the Berlin Conference of 1884–85 was held to regulate the competition between the European powers in what was called the "Scramble for Africa" by defining "effective occupation" as the criterion for international recognition of territorial claims.[128] The scramble continued into the 1890s, and caused Britain to reconsider its decision in 1885 to withdraw from Sudan. A joint force of British and Egyptian troops defeated the Mahdist Army in 1896, and rebuffed an attempted French invasion at Fashoda in 1898. Sudan was nominally made an Anglo-Egyptian condominium, but a British colony in reality.[129]

British gains in Southern and East Africa prompted Cecil Rhodes, pioneer of British expansion in Southern Africa, to urge a "Cape to Cairo" railway linking the strategically important Suez Canal to the mineral-rich south of the continent.[130] During the 1880s and 1890s, Rhodes, with his privately owned British South Africa Company, occupied and annexed territories subsequently named after him, Rhodesia.[131]

Changing status of the white colonies

Canada's major industry in terms of employment and value of the product was the timber trade (Ontario, 1900 circa).

The path to independence for the white colonies of the British Empire began with the 1839 Durham Report, which proposed unification and self-government for Upper and Lower Canada, as a solution to political unrest which had erupted in armed rebellions in 1837.[132] This began with the passing of the Act of Union in 1840, which created the Province of Canada. Responsible government was first granted to Nova Scotia in 1848, and was soon extended to the other British North American colonies. With the passage of the British North America Act, 1867 by the British Parliament, Upper and Lower Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were formed into the Dominion of Canada, a confederation enjoying full self-government with the exception of international relations.[133] Australia and New Zealand achieved similar levels of self-government after 1900, with the Australian colonies federating in 1901.[134] The term "dominion status" was officially introduced at the Colonial Conference of 1907.[135]

The last decades of the 19th century saw concerted political campaigns for Irish home rule. Ireland had been united with Britain into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland with the Act of Union 1800 after the Irish Rebellion of 1798, and had suffered a severe famine between 1845 and 1852. Home rule was supported by the British Prime minister, William Gladstone, who hoped that Ireland might follow in Canada's footsteps as a Dominion within the empire, but his 1886 Home Rule bill was defeated in Parliament. Although the bill, if passed, would have granted Ireland less autonomy within the UK than the Canadian provinces had within their own federation,[136] many MPs feared that a partially independent Ireland might pose a security threat to Great Britain or mark the beginning of the break-up of the empire.[137] A second Home Rule bill was also defeated for similar reasons.[137] A third bill was passed by Parliament in 1914, but not implemented because of the outbreak of the First World War leading to the 1916 Easter Rising.[138]

World wars (1914–1945)

By the turn of the 20th century, fears had begun to grow in Britain that it would no longer be able to defend the metropole and the entirety of the empire while at the same time maintaining the policy of "splendid isolation".[139] Germany was rapidly rising as a military and industrial power and was now seen as the most likely opponent in any future war. Recognising that it was overstretched in the Pacific[140] and threatened at home by the Imperial German Navy, Britain formed an alliance with Japan in 1902 and with its old enemies France and Russia in 1904 and 1907, respectively.[141]

First World War

Soldiers of the Australian 5th Division, waiting to attack during the Battle of Fromelles, 19 July 1916

Britain's fears of war with Germany were realised in 1914 with the outbreak of the First World War. Britain quickly invaded and occupied most of Germany's overseas colonies in Africa. In the Pacific, Australia and New Zealand occupied German New Guinea and Samoa respectively. Plans for a post-war division of the Ottoman Empire, which had joined the war on Germany's side, were secretly drawn up by Britain and France under the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement. This agreement was not divulged to the Sharif of Mecca, who the British had been encouraging to launch an Arab revolt against their Ottoman rulers, giving the impression that Britain was supporting the creation of an independent Arab state.[142]

A poster urging men from countries of the British Empire to enlist in the British Army

The British declaration of war on Germany and its allies also committed the colonies and Dominions, which provided invaluable military, financial and material support. Over 2.5 million men served in the armies of the Dominions, as well as many thousands of volunteers from the Crown colonies.[143] The contributions of Australian and New Zealand troops during the 1915 Gallipoli Campaign against the Ottoman Empire had a great impact on the national consciousness at home, and marked a watershed in the transition of Australia and New Zealand from colonies to nations in their own right. The countries continue to commemorate this occasion on Anzac Day. Canadians viewed the Battle of Vimy Ridge in a similar light.[144] The important contribution of the Dominions to the war effort was recognised in 1917 by the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George when he invited each of the Dominion Prime Ministers to join an Imperial War Cabinet to co-ordinate imperial policy.[145]

Under the terms of the concluding Treaty of Versailles signed in 1919, the empire reached its greatest extent with the addition of 1,800,000 square miles (4,700,000 km2) and 13 million new subjects.[146] The colonies of Germany and the Ottoman Empire were distributed to the Allied powers as League of Nations mandates. Britain gained control of Palestine, Transjordan, Iraq, parts of Cameroon and Togoland, and Tanganyika. The Dominions themselves also acquired mandates of their own: the Union of South Africa gained South West Africa (modern-day Namibia), Australia gained New Guinea, and New Zealand Western Samoa. Nauru was made a combined mandate of Britain and the two Pacific Dominions.[147]

Inter-war period

British Empire at its territorial peak in 1921

The changing world order that the war had brought about, in particular the growth of the United States and Japan as naval powers, and the rise of independence movements in India and Ireland, caused a major reassessment of British imperial policy.[148] Forced to choose between alignment with the United States or Japan, Britain opted not to renew its Japanese alliance and instead signed the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, where Britain accepted naval parity with the United States.[149] This decision was the source of much debate in Britain during the 1930s[150] as militaristic governments took hold in Germany and Japan helped in part by the Great Depression, for it was feared that the empire could not survive a simultaneous attack by both nations.[151] The issue of the empire's security was a serious concern in Britain, as it was vital to the British economy.[152]

In 1919, the frustrations caused by delays to Irish home rule led the MPs of Sinn Féin, a pro-independence party that had won a majority of the Irish seats in the 1918 British general election, to establish an independent parliament in Dublin, at which Irish independence was declared. The Irish Republican Army simultaneously began a guerrilla war against the British administration.[153] The Anglo-Irish War ended in 1921 with a stalemate and the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, creating the Irish Free State, a Dominion within the British Empire, with effective internal independence but still constitutionally linked with the British Crown.[154]Northern Ireland, consisting of six of the 32 Irish counties which had been established as a devolved region under the 1920 Government of Ireland Act, immediately exercised its option under the treaty to retain its existing status within the United Kingdom.[155]

George V with the British and Dominion prime ministers at the 1926 Imperial Conference

A similar struggle began in India when the Government of India Act 1919 failed to satisfy demand for independence.[156] Concerns over communist and foreign plots following the Ghadar Conspiracy ensured that war-time strictures were renewed by the Rowlatt Acts. This led to tension,[157] particularly in the Punjab region, where repressive measures culminated in the Amritsar Massacre. In Britain public opinion was divided over the morality of the massacre, between those who saw it as having saved India from anarchy, and those who viewed it with revulsion.[157] The subsequent Non-Co-Operation movement was called off in March 1922 following the Chauri Chaura incident, and discontent continued to simmer for the next 25 years.[158]

In 1922, Egypt, which had been declared a British protectorate at the outbreak of the First World War, was granted formal independence, though it continued to be a British client state until 1954. British troops remained stationed in Egypt until the signing of the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty in 1936,[159] under which it was agreed that the troops would withdraw but continue to occupy and defend the Suez Canal zone. In return, Egypt was assisted in joining the League of Nations.[160]Iraq, a British mandate since 1920, also gained membership of the League in its own right after achieving independence from Britain in 1932.[161] In Palestine, Britain was presented with the problem of mediating between the Arabs and increasing numbers of Jews. The 1917 Balfour Declaration, which had been incorporated into the terms of the mandate, stated that a national home for the Jewish people would be established in Palestine, and Jewish immigration allowed up to a limit that would be determined by the mandatory power.[162] This led to increasing conflict with the Arab population, who openly revolted in 1936. As the threat of war with Germany increased during the 1930s, Britain judged the support of Arabs as more important than the establishment of a Jewish homeland, and shifted to a pro-Arab stance, limiting Jewish immigration and in turn triggering a Jewish insurgency.[142]

The right of the Dominions to set their own foreign policy, independent of Britain, was recognised at the 1923 Imperial Conference.[163] Britain's request for military assistance from the Dominions at the outbreak of the Chanak Crisis the previous year had been turned down by Canada and South Africa, and Canada had refused to be bound by the Treaty of Lausanne (1923).[164][165] After pressure from the Irish Free State and South Africa, the 1926 Imperial Conference issued the Balfour Declaration of 1926, declaring the Dominions to be "autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another" within a "British Commonwealth of Nations".[166] This declaration was given legal substance under the 1931 Statute of Westminster.[135] The parliaments of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, the Irish Free State and Newfoundland were now independent of British legislative control, they could nullify British laws and Britain could no longer pass laws for them without their consent.[167] Newfoundland reverted to colonial status in 1933, suffering from financial difficulties during the Great Depression.[168] The Irish Free State distanced itself further from the British state with the introduction of a new constitution in 1937, making it a republic in all but name.[169]

Second World War

During the Second World War, the Eighth Army was made up of units from many different countries in the British Empire and Commonwealth; it fought in North African and Italian campaigns.

Britain's declaration of war against Nazi Germany in September 1939 included the Crown colonies and India but did not automatically commit the Dominions of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Newfoundland and South Africa. All soon declared war on Germany, but Ireland chose to remain legally neutral throughout the war.[170]

After the Fall of France in June 1940, Britain and the empire stood alone against Germany, until the German invasion of Greece on 7 April 1941. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill successfully lobbied President Franklin D. Roosevelt for military aid from the United States, but Roosevelt was not yet ready to ask Congress to commit the country to war.[171] In August 1941, Churchill and Roosevelt met and signed the Atlantic Charter, which included the statement that "the rights of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they live" should be respected. This wording was ambiguous as to whether it referred to European countries invaded by Germany and Italy, or the peoples colonised by European nations, and would later be interpreted differently by the British, Americans, and nationalist movements.[172][173]

In December 1941, Japan launched, in quick succession, attacks on British Malaya, the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, and Hong Kong. Churchill's reaction to the entry of the United States into the war was that Britain was now assured of victory and the future of the empire was safe,[174] but the manner in which British forces were rapidly defeated in the Far East irreversibly harmed Britain's standing and prestige as an imperial power.[175][176] Most damaging of all was the Fall of Singapore, which had previously been hailed as an impregnable fortress and the eastern equivalent of Gibraltar.[177] The realisation that Britain could not defend its entire empire pushed Australia and New Zealand, which now appeared threatened by Japanese forces, into closer ties with the United States. This resulted in the 1951 ANZUS Pact between Australia, New Zealand and the United States of America.[172]

Decolonisation and decline (1945–1997)

Though Britain and the empire emerged victorious from the Second World War, the effects of the conflict were profound, both at home and abroad. Much of Europe, a continent that had dominated the world for several centuries, was in ruins, and host to the armies of the United States and the Soviet Union, who now held the balance of global power.[178] Britain was left essentially bankrupt, with insolvency only averted in 1946 after the negotiation of a $US 4.33 billion loan from the United States,[179] the last instalment of which was repaid in 2006.[180] At the same time, anti-colonial movements were on the rise in the colonies of European nations. The situation was complicated further by the increasing Cold War rivalry of the United States and the Soviet Union. In principle, both nations were opposed to European colonialism. In practice, however, American anti-communism prevailed over anti-imperialism, and therefore the United States supported the continued existence of the British Empire to keep Communist expansion in check.[181] The "wind of change" ultimately meant that the British Empire's days were numbered, and on the whole, Britain adopted a policy of peaceful disengagement from its colonies once stable, non-Communist governments were available to transfer power to. This was in contrast to other European powers such as France and Portugal,[182] which waged costly and ultimately unsuccessful wars to keep their empires intact. Between 1945 and 1965, the number of people under British rule outside the UK itself fell from 700 million to five million, three million of whom were in Hong Kong.[183]

Initial disengagement

About 14.5 million people lost their homes as a result of the partition of India in 1947.

The pro-decolonisation Labour government, elected at the 1945 general election and led by Clement Attlee, moved quickly to tackle the most pressing issue facing the empire: Indian independence.[184] India's two major political parties—the Indian National Congress (led by Mahatma Gandhi) and the Muslim League (led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah)—had been campaigning for independence for decades, but disagreed as to how it should be implemented. Congress favoured a unified secular Indian state, whereas the League, fearing domination by the Hindu majority, desired a separate Islamic state for Muslim-majority regions. Increasing civil unrest and the mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy during 1946 led Attlee to promise independence no later than 30 June 1948. When the urgency of the situation and risk of civil war became apparent, the newly appointed (and last) Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, hastily brought forward the date to 15 August 1947.[185] The borders drawn by the British to broadly partition India into Hindu and Muslim areas left tens of millions as minorities in the newly independent states of India and Pakistan.[186] Millions of Muslims subsequently crossed from India to Pakistan and Hindus vice versa, and violence between the two communities cost hundreds of thousands of lives. Burma, which had been administered as part of the British Raj, and Sri Lanka gained their independence the following year in 1948. India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka became members of the Commonwealth, while Burma chose not to join.[187]

The British mandate in Palestine, where an Arab majority lived alongside a Jewish minority, presented the British with a similar problem to that of India.[188] The matter was complicated by large numbers of Jewish refugees seeking to be admitted to Palestine following the Holocaust, while Arabs were opposed to the creation of a Jewish state. Frustrated by the intractability of the problem, attacks by Jewish paramilitary organisations and the increasing cost of maintaining its military presence, Britain announced in 1947 that it would withdraw in 1948 and leave the matter to the United Nations to solve.[189] The UN General Assembly subsequently voted for a plan to partition Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state.

Following the surrender of Japan in the Second World War, anti-Japanese resistance movements in Malaya turned their attention towards the British, who had moved to quickly retake control of the colony, valuing it as a source of rubber and tin.[190] The fact that the guerrillas were primarily Malayan-Chinese Communists meant that the British attempt to quell the uprising was supported by the Muslim Malay majority, on the understanding that once the insurgency had been quelled, independence would be granted.[190] The Malayan Emergency, as it was called, began in 1948 and lasted until 1960, but by 1957, Britain felt confident enough to grant independence to the Federation of Malaya within the Commonwealth. In 1963, the 11 states of the federation together with Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo joined to form Malaysia, but in 1965 Chinese-majority Singapore was expelled from the union following tensions between the Malay and Chinese populations.[191]Brunei, which had been a British protectorate since 1888, declined to join the union[192] and maintained its status until independence in 1984.

Suez and its aftermath

British Prime Minister Anthony Eden's decision to invade Egypt during the Suez Crisis ended his political career and revealed Britain's weakness as an imperial power.

In 1951, the Conservative Party returned to power in Britain, under the leadership of Winston Churchill. Churchill and the Conservatives believed that Britain's position as a world power relied on the continued existence of the empire, with the base at the Suez Canal allowing Britain to maintain its pre-eminent position in the Middle East in spite of the loss of India. However, Churchill could not ignore Gamal Abdul Nasser's new revolutionary government of Egypt that had taken power in 1952, and the following year it was agreed that British troops would withdraw from the Suez Canal zone and that Sudan would be granted self-determination by 1955, with independence to follow.[193]Sudan was granted independence on 1 January 1956.

In July 1956, Nasser unilaterally nationalised the Suez Canal. The response of Anthony Eden, who had succeeded Churchill as Prime Minister, was to collude with France to engineer an Israeli attack on Egypt that would give Britain and France an excuse to intervene militarily and retake the canal.[194] Eden infuriated US President Dwight D. Eisenhower, by his lack of consultation, and Eisenhower refused to back the invasion.[195] Another of Eisenhower's concerns was the possibility of a wider war with the Soviet Union after it threatened to intervene on the Egyptian side. Eisenhower applied financial leverage by threatening to sell US reserves of the British pound and thereby precipitate a collapse of the British currency.[196] Though the invasion force was militarily successful in its objectives,[197] UN intervention and US pressure forced Britain into a humiliating withdrawal of its forces, and Eden resigned.[198][199]

The Suez Crisis very publicly exposed Britain's limitations to the world and confirmed Britain's decline on the world stage, demonstrating that henceforth it could no longer act without at least the acquiescence, if not the full support, of the United States.[200][201][202] The events at Suez wounded British national pride, leading one MP to describe it as "Britain's Waterloo"[203] and another to suggest that the country had become an "American satellite".[204]Margaret Thatcher later described the mindset she believed had befallen Britain's political leaders after Suez where they "went from believing that Britain could do anything to an almost neurotic belief that Britain could do nothing", from which Britain did not recover until the successful recapture of the Falkland Islands from Argentina in 1982.[205]

While the Suez Crisis caused British power in the Middle East to weaken, it did not collapse.[206] Britain again deployed its armed forces to the region, intervening in Oman (1957), Jordan (1958) and Kuwait (1961), though on these occasions with American approval,[207] as the new Prime Minister Harold Macmillan's foreign policy was to remain firmly aligned with the United States.[203] Britain maintained a military presence in the Middle East for another decade. On 16 January 1968, a few weeks after the devaluation of the pound, Prime Minister Harold Wilson and his Defence Secretary Denis Healey announced that British troops would be withdrawn from major military bases East of Suez, which included the ones in the Middle East, and primarily from Malaysia and Singapore by the end of 1971, instead of 1975 as earlier planned.[208] By that time over 50,000 British military personnel were still stationed in the Far East, including 30,000 in Singapore.[209] The British withdrew from Aden in 1967, Bahrain in 1971, and the Maldives in 1976.[210]

Wind of change

British Empire by 1959

Macmillan gave a speech in Cape Town, South Africa in February 1960 where he spoke of "the wind of change blowing through this continent".[211] Macmillan wished to avoid the same kind of colonial war that France was fighting in Algeria, and under his premiership decolonisation proceeded rapidly.[212] To the three colonies that had been granted independence in the 1950s—Sudan, the Gold Coast and Malaya—were added nearly ten times that number during the 1960s.[213]

Britain's remaining colonies in Africa, except for self-governing Southern Rhodesia, were all granted independence by 1968. British withdrawal from the southern and eastern parts of Africa was not a peaceful process. Kenyan independence was preceded by the eight-year Mau Mau Uprising. In Rhodesia, the 1965 Unilateral Declaration of Independence by the white minority resulted in a civil war that lasted until the Lancaster House Agreement of 1979, which set the terms for recognised independence in 1980, as the new nation of Zimbabwe.[214]

British decolonisation in Africa. By the end of the 1960s, all but Rhodesia (the future Zimbabwe) and the South African mandate of South West Africa (Namibia) had achieved recognised independence.

In the Mediterranean, a guerrilla war waged by Greek Cypriots ended in 1960 leading to an independent Cyprus, with the UK retaining the military bases of Akrotiri and Dhekelia. The Mediterranean islands of Malta and Gozo were amicably granted independence from the UK in 1964 and became the country of Malta, though the idea had been raised in 1955 of integration with Britain.[215]

Most of the UK's Caribbean territories achieved independence after the departure in 1961 and 1962 of Jamaica and Trinidad from the West Indies Federation, established in 1958 in an attempt to unite the British Caribbean colonies under one government, but which collapsed following the loss of its two largest members.[216]Barbados achieved independence in 1966 and the remainder of the eastern Caribbean islands in the 1970s and 1980s,[216] but Anguilla and the Turks and Caicos Islands opted to revert to British rule after they had already started on the path to independence.[217] The British Virgin Islands,[218]Cayman Islands and Montserrat opted to retain ties with Britain,[219] while Guyana achieved independence in 1966. Britain's last colony on the American mainland, British Honduras, became a self-governing colony in 1964 and was renamed Belize in 1973, achieving full independence in 1981. A dispute with Guatemala over claims to Belize was left unresolved.[220]

British territories in the Pacific acquired independence in the 1970s beginning with Fiji in 1970 and ending with Vanuatu in 1980. Vanuatu's independence was delayed because of political conflict between English and French-speaking communities, as the islands had been jointly administered as a condominium with France.[221] Fiji,[222]Tuvalu, the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea chose to become Commonwealth realms.

End of empire

In 1980, Southern Rhodesia, Britain's last African colony, became the independent nation of Zimbabwe. The New Hebrides achieved independence (as Vanuatu) in 1980, with Belize following suit in 1981. The passage of the British Nationality Act 1981, which reclassified the remaining Crown colonies as "British Dependent Territories" (renamed British Overseas Territories in 2002)[223] meant that, aside from a scattering of islands and outposts, the process of decolonisation that had begun after the Second World War was largely complete. In 1982, Britain's resolve in defending its remaining overseas territories was tested when Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, acting on a long-standing claim that dated back to the Spanish Empire.[224] Britain's ultimately successful military response to retake the islands during the ensuing Falklands War was viewed by many to have contributed to reversing the downward trend in Britain's status as a world power.[225] The same year, the Canadian government severed its last legal link with Britain by patriating the Canadian constitution from Britain. The 1982 Canada Act passed by the British parliament ended the need for British involvement in changes to the Canadian constitution.[19] Similarly, the Australia Act 1986 (effective 3 March 1986) severed the constitutional link between Britain and the Australian states, while New Zealand's Constitution Act 1986 (effective 1 January 1987) reformed the constitution of New Zealand to sever its constitutional link with Britain.[226] In 1984, Brunei, Britain's last remaining Asian protectorate, gained its independence.

In September 1982 the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, travelled to Beijing to negotiate with the Chinese government, on the future of Britain's last major and most populous overseas territory, Hong Kong.[227] Under the terms of the 1842 Treaty of Nanking and 1860 Convention of Peking, Hong Kong Island and Kowloon Peninsula had been respectively ceded to Britain in perpetuity, but the vast majority of the colony was constituted by the New Territories, which had been acquired under a 99-year lease in 1898, due to expire in 1997.[228][229] Thatcher, seeing parallels with the Falkland Islands, initially wished to hold Hong Kong and proposed British administration with Chinese sovereignty, though this was rejected by China.[230] A deal was reached in 1984—under the terms of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, Hong Kong would become a special administrative region of the People's Republic of China, maintaining its way of life for at least 50 years.[231] The handover ceremony in 1997 marked for many,[17] including Charles, Prince of Wales,[18] who was in attendance, "the end of Empire".[19][20]

Legacy

The fourteen British Overseas Territories

Britain retains sovereignty over 14 territories outside the British Isles, which were renamed the British Overseas Territories in 2002.[232] Three are uninhabited except for transient military or scientific personnel;[232] the remaining eleven are self-governing to varying degrees and are reliant on the UK for foreign relations and defence. The British government has stated its willingness to assist any Overseas Territory that wishes to proceed to independence, where that is an option,[233] and three territories have specifically voted to remain under British sovereignty (Bermuda in 1995, Gibraltar in 2002 and the Falkland Islands in 2013).[234]

British sovereignty of several of the overseas territories is disputed by their geographical neighbours: Gibraltar is claimed by Spain, the Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands are claimed by Argentina, and the British Indian Ocean Territory is claimed by Mauritius and Seychelles.[235] The British Antarctic Territory is subject to overlapping claims by Argentina and Chile, while many countries do not recognise any territorial claims in Antarctica.[236]

Most former British colonies and protectorates are among the 52 member states of the Commonwealth of Nations, a non-political, voluntary association of equal members, comprising a population of around 2.2 billion people.[237] Sixteen Commonwealth realms voluntarily continue to share the British monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, as their head of state. These sixteen nations are distinct and equal legal entities – the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Grenada, Jamaica, Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Solomon Islands and Tuvalu.[238]

Parliament House in Canberra, Australia. Britain's Westminster System of governance has left a legacy of parliamentary democracies in many former colonies.

Decades, and in some cases centuries, of British rule and emigration have left their mark on the independent nations that arose from the British Empire. The empire established the use of English in regions around the world. Today it is the primary language of up to 460 million people and is spoken by about one and a half billion as a first, second or foreign language.[239]

The spread of English from the latter half of the 20th century has been helped in part by the cultural and economic influence of the United States, itself originally formed from British colonies. Except in Africa where nearly all the former colonies have adopted the presidential system, the English parliamentary system has served as the template for the governments for many former colonies, and English common law for legal systems.[240]

Cricket being played in India. British sports continue to be supported in various parts of the former empire.

The British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council still serves as the highest court of appeal for several former colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific. British missionaries who travelled around the globe often in advance of soldiers and civil servants spread Protestantism (including Anglicanism) to all continents. The British Empire provided refuge for religiously persecuted continental Europeans for hundreds of years.[241] British colonial architecture, such as in churches, railway stations and government buildings, can be seen in many cities that were once part of the British Empire.[242]

Individual and team sports developed in Britain — particularly golf, football, cricket, rugby, netball, lawn bowls, hockey and lawn tennis — were also exported.[243] The British choice of system of measurement, the imperial system, continues to be used in some countries in various ways. The convention of driving on the left hand side of the road has been retained in much of the former empire.[244]

Political boundaries drawn by the British did not always reflect homogeneous ethnicities or religions, contributing to conflicts in formerly colonised areas. The British Empire was also responsible for large migrations of peoples. Millions left the British Isles, with the founding settler populations of the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand coming mainly from Britain and Ireland. Tensions remain between the white settler populations of these countries and their indigenous minorities, and between white settler minorities and indigenous majorities in South Africa and Zimbabwe. Settlers in Ireland from Great Britain have left their mark in the form of divided nationalist and unionist communities in Northern Ireland. Millions of people moved to and from British colonies, with large numbers of Indians emigrating to other parts of the empire, such as Malaysia and Fiji, and Chinese people to Malaysia, Singapore and the Caribbean.[245] The demographics of Britain itself were changed after the Second World War owing to immigration to Britain from its former colonies.[246]

See also

|

- All-Red Route

- British Empire Exhibition

- British Empire in fiction

- Colonial Office

- Crown Colonies

- Demographics of the British Empire

- Economy of the British Empire

- Historical flags of the British Empire

- Foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- Government Houses of the British Empire and Commonwealth

- Historiography of the British Empire

- History of capitalism

- History of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom

- Indirect rule

- List of British Empire-related topics

- Order of the British Empire

- Territorial evolution of the British Empire

References

^ Ferguson 2004b.

^ Maddison 2001, pp. 97 "The total population of the Empire was 412 million [in 1913]", 241 "[World population in 1913 (in thousands):] 1 791 020".

^ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 502. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 10 September 2016.land: 148.94 million sq km

^ Jackson, pp. 5-6.

^ Russo 2012, p. 15 chapter 1 'Great Expectations': "The dramatic rise in Spanish fortunes sparked both envy and fear among northern, mostly Protestant, Europeans.".

^ abc Ferguson 2004b, p. 3.

^ Tellier, L.-N. (2009). Urban World History: an Economic and Geographical Perspective. Quebec: PUQ. p. 463.

ISBN 2-7605-1588-5.

^ Johnston, pp. 508–10.

^ ab Porter, p. 332.

^ Sondhaus, L. (2004). Navies in Modern World History. London: Reaktion Books. p. 9.

ISBN 1-86189-202-0.

^ "The Workshop of the World". BBC History. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

^ ab Porter, p. 8.

^ Marshall, pp. 156-57.

^ Tompson, Richard S. (2003). Great Britain: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present. New York: Facts on File. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8160-4474-0.

^ Hosch, William L. (2009). World War I: People, Politics, and Power. America at War. New York: Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-61530-048-8.

^ ab Brendon, p. 660.

^ ab "Charles' diary lays thoughts bare". BBC News. 22 February 2006. Retrieved 13 December 2008.

^ abc Brown, p. 594.

^ ab "Britain, the Commonwealth and the End of Empire". BBC News. Retrieved 13 December 2008.

^ Andrews 1985, p. 45.

^ Ferguson 2004b, p. 4.

^ Canny, p. 35.

^ Koebner, Richard (May 1953). "The Imperial Crown of This Realm: Henry VIII, Constantine the Great, and Polydore Vergil". Historical Research. 26 (73): 29–52. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1953.tb02124.x. ISSN 1468-2281.

^ Thomas, pp. 155–58

^ Ferguson 2004b, p. 7.

^ Canny, p. 62.

^ Lloyd, pp. 4–8.

^ Canny, p. 7.

^ Kenny, p. 5.

^ Taylor, pp. 119,123.

^ Andrews, p. 187.

^ Andrews, p. 188.

^ Canny, p. 63.

^ Canny, pp. 63–64.

^ Canny, p. 70.

^ Canny, p. 34.

^ James, p. 17.

^ Canny, p. 71.

^ Canny, p. 221.

^ Lloyd, pp. 22–23.

^ Lloyd, p. 32.

^ Lloyd, pp. 33, 43.

^ Lloyd, pp. 15–20.

^ Andrews, pp. 316, 324–26.

^ Andrews, pp. 20–22.

^ James, p. 8.

^ Lloyd, p. 40.

^ Ferguson 2004b, pp. 72–73.

^ ab Buckner, p. 25.

^ Lloyd, p. 37.

^ Ferguson 2004b, p. 62.

^ Canny, p. 228.

^ Marshall, pp. 440–64.

^ Magnusson, p. 531.

^ Macaulay, p. 509.

^ Lloyd, p. 13.

^ ab Ferguson 2004b, p. 19.

^ Canny, p. 441.

^ Pagden, p. 90.

^ ab Shennan, pp. 11–17.

^ James, p. 58.

^ Smith, p. 17.

^ Bandyopādhyāẏa, pp. 49–52

^ Smith, pp. 18–19.

^ ab Pagden, p. 91.

^ Ferguson 2004b, p. 84.

^ Marshall, pp. 312–23.

^ Canny, p. 92.

^ James, p. 120.

^ James, p. 119.

^ Marshall, p. 585.

^ Zolberg, p. 496.

^ Games, pp. 46–48.

^ Kelley & Trebilcock, p. 43.

^ Smith, p. 28.

^ Latimer, pp. 8, 30–34, 389–92.

^ Marshall, pp. 388.

^ Smith, p. 20.

^ Smith, pp. 20–21.

^ Mulligan & Hill, pp. 20–23.

^ Peters, pp. 5–23.

^ James, p. 142.

^ Britain and the Dominions, p. 159.

^ Fieldhouse, pp. 145–49

^ Cervero, Robert B. (1998). The Transit Metropolis: A Global Inquiry. Chicago: Island Press. p. 320. ISBN 1-55963-591-6.

^ Statesmen's Year Book 1889

^ Smith, p. 45.

^ "Waitangi Day". History Group, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 13 December 2008.

^ Porter, p. 579.

^ Mein Smith, p. 49.

^ James, p. 152.

^ Lloyd, pp. 115–118.

^ James, p. 165.

^ "Why was Slavery finally abolished in the British Empire?". The Abolition Project. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

^ Porter, p. 14.

^ Hinks, p. 129.

^ Hyam, p. 1.

^ Smith, p. 71.

^ Parsons, p. 3.

^ ab Porter, p. 401.

^ Lee 1994, pp. 254–57.

^ Marshall, pp. 156–57.

^ Dalziel, pp. 88–91.

^ Mori, p. 178.

^ Martin, pp. 146–48.

^ Janin, p. 28.

^ Keay, p. 393

^ Parsons, pp. 44–46.

^ Smith, pp. 50–57.

^ Brown, p. 5.

^ Marshall, pp. 133–34.

^ Hopkirk, pp. 1–12.

^ James, p. 181.

^ abc James, p. 182.

^ Royle, preface.

^ Williams, Beryl J. (1966). "The Strategic Background to the Anglo-Russian Entente of August 1907". The Historical Journal. 9 (3): 360–73. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00026698. JSTOR 2637986.

^ Hodge, p. 47.

^ Smith, p. 85.

^ Smith, pp. 85–86.

^ Lloyd, pp. 168, 186, 243.

^ Lloyd, p. 255.

^ Tilby, p. 256.

^ Roger 1986, p. 718.

^ Ferguson 2004b, pp. 230–33.

^ James, p. 274.

^ "Treaties". Egypt Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 15 September 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

^ Herbst, pp. 71–72.

^ Vandervort, pp. 169–83.

^ James, p. 298.

^ Lloyd, p. 215.

^ Smith, pp. 28–29.

^ Porter, p. 187

^ Smith, p. 30.

^ ab Rhodes, Wanna & Weller, pp. 5–15.

^ Lloyd, p. 213

^ ab James, p. 315.

^ Smith, p. 92.

^ O'Brien, p. 1.

^ Brown, p. 667.

^ Lloyd, p. 275.

^ ab Brown, pp. 494–95.

^ Marshall, pp. 78–79.

^ Lloyd, p. 277.

^ Lloyd, p. 278.

^ Ferguson 2004b, p. 315.

^ Fox, pp. 23–29, 35, 60.

^ Goldstein, p. 4.

^ Louis, p. 302.

^ Louis, p. 294.

^ Louis, p. 303.

^ Lee 1996, p. 305.

^ Brown, p. 143.

^ Smith, p. 95.

^ Magee, p. 108.

^ Ferguson 2004b, p. 330.

^ ab James, p. 416.

^ Low, D.A. (February 1966). "The Government of India and the First Non-Cooperation Movement – 1920–1922". The Journal of Asian Studies. 25 (2): 241–59. doi:10.2307/2051326. JSTOR 2051326.

^ Smith, p. 104.

^ Brown, p. 292.

^ Smith, p. 101.

^ Louis, p. 271.

^ McIntyre, p. 187.

^ Brown, p. 68.

^ McIntyre, p. 186.

^ Brown, p. 69.

^ Turpin & Tomkins, p. 48.

^ Lloyd, p. 300.

^ Kenny, p. 21.

^ Lloyd, pp. 313–14.

^ Gilbert, p. 234.

^ ab Lloyd, p. 316.