Vigraharaja IV

| Vigraharaja IV | |

|---|---|

A coin of Vigraharaja IV | |

| King of Shakambhari | |

| Reign | c. 1150-1164 CE |

| Predecessor | Jagaddeva |

| Successor | Amaragangeya |

| Dynasty | Chahamanas of Shakambhari |

| Father | Arnoraja |

Find spots of inscriptions of Vigraharaja IV

Vigraharāja IV (r. c. 1150-1164 CE), also known as Visaladeva, was an Indian king belonging to the Chahamana dynasty of north-western India. He turned the Chahamana kingdom into an empire by subduing nearly all the neighbouring kings. His kingdom included the parts of present-day Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi.

Vigraharaja commissioned several buildings in his capital Ajayameru (modern Ajmer), most of which were destroyed or converted to Muslim structures after the Muslim conquest of Ajmer. These include a Sanskrit centre of learning that was later converted into the Adhai Din Ka Jhonpra mosque. Harakeli Nataka, a Sanskrit-language drama written by him, is inscribed on inscriptions discovered at the mosque site.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Military career

2.1 Chaulukyas of Gujarat

2.1.1 Chahamanas of Naddula

2.2 Tomaras of Delhi

2.3 Turushkas

2.4 Other conquests

3 Cultural activities

4 References

4.1 Bibliography

Early life

Vigraharaja was born to the Chahamana king Arnoraja. Vigraharaja's elder brother and predecessor Jagaddeva killed their father. Their half-brother, Someshvara, was brought up in Gujarat by his Chaulukya maternal relatives. Vigraharaja probably ascended the throne after killing Jaggaddeva to avenge their father's death.[1]

Military career

The 1164 CE Delhi-Shivalik pillar inscription states that Vigraharaja conquered the region between the Himalayas and the Vindhyas. The Himalayas and the Vindhyas form the traditional boundary of Aryavarta (the land of ancient Aryans), and Vigraharaja claimed to have restored the rule of Aryans in this land. While his claim of having conquered the entire land between these two mountains is an exaggeration, it is not completely baseless. His Delhi-Shivalik pillar inscription was found at Topra village in Haryana, near the Shivalik Hills. This indicates that Vigraharaja captured territories to the north of Delhi, up to the Himalayan foothills.[2] Raviprabha's Dharmaghosha-Suri-Stuti states that the ruler of Malwa and Arisiha (possibly Arisimha of Mewar) assisted him in hoisting a flag at the Rajavihara Jain temple in Ajmer. The ruler of Malwa here probably refers to a claimant to the Paramara kingdom, which had been captured by the Chaulukyas during this period. Assuming that the claimant to the Malwa throne had accepted Vigraharaja's suzerainty, it appears that Vigraharaja's influence extended up to the Vindhyas, at least in name.[3]

His kingdom included the present-day Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi. It probably also included a part of Punjab (to the south-east of Sutlej river) and a portion of the northern Gangetic plain (to the west of Yamuna).[4]

The play Lalita-Vigraharaja-Nataka, composed by Vigraharaja's court poet, claims that his army included 1 million men; 100,000 horses; and 1,000 elephants.[4]

Chaulukyas of Gujarat

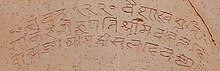

Visaladeva inscription on Delhi-Topra pillar, 12th century.

Vigraharaja's father Arnoraja had suffered a humiliating at the hands of Kumarapala, the Chaulukya king of Gujarat. Vigraharaja launched several expeditions against the Chaulukyas to avenge his father's defeat.[1]

According to the Bijolia rock inscription, he killed one Sajjana. The inscription describes Sajjana as "the most wicked person of the land", who was sent to the abode of Yama (the god of death) by Vigraharaja. Historian Dasharatha Sharma identified Sajjana with Kumarapala's governor (daṇḍāhiśa) of Chittor. According to the Jain author Somatilaka Suri, Vigraharaja's army captured Sajjana's elephant force. While Vigraharaja was busy fighting at Chittor, Kumarapala tried to create a diversion by besieging Nagor, but lifted the siege after learning about Vigraharaja's victory at Chittor.[5]

A Chahamana prashasti (eulogy) boasts that Vigraharaja reduced Kumarapala to a karavalapala (probably the designation of a subordinate officer). This is obviously an exaggeration, but it does appear that Vigraharaja conquered some of Kumarapala's territories. The earliest Chahamana inscriptions from the Bijolia-Jahazpur-Mandalgarh area are dated to Vigraharaja's reign.[6]

Chahamanas of Naddula

The Bisaldeo temple in Bisalpur was constructed by Vigraharaja IV

Vigraharaja subdued the Chahamanas of Naddula, who had branched off from the Shakambhari Chahamana dynasty, and were feudatories of the Chaulukya king Kumarapala.[7] The Bijolia inscription boasts that he turned Javalipura (modern Jalore) into "Jvalapura" (city of flames); reduced Pallika (modern Pali) to a palli (a hamlet); and made Naddula (modern Nadol) a nadvala (a cane-stick or a marsh of reeds).[8][9] The Naddula ruler subdued by him was probably Alhanadeva.[2]

Vigraharaja also defeated one Kuntapala, who can be identified with a Naddula Chahamana subordinate of Kumarapala.[10]

Tomaras of Delhi

The Bijolia rock inscription states that Vigraharaja conquered Ashika (identified with Hansi) and Delhi.[11] The Chahamanas had been involved in conflicts with the Tomaras of Delhi since the time of his ancestor Chandanaraja. Vigraharaja put an end to this long conflict by decisively defeating the Tomaras, who had grown weak under attacks from the Chahamanas, the Gahadavalas and the Muslims. The Tomaras continued to rule for a few more decades, but as vassals of the Chahamanas.[12]

An old bahi (manuscript) states that Visaladeva i.e. Vigraharaja captured Delhi from Tamvars (Tomaras) in the year 1152 CE (1209 VS).[13] According to historian R. B. Singh, Hansi might have been under Muslim control by this time.[11] On the other hand, Dasharatha Sharma theorizes that the Tomaras had recaptured Hansi from Ghaznavids by this time, and Vigraharaja captured it from the Tomaras.[12]

The legendary epic poem Prithviraj Raso states that the later Chahamana king Prithviraja III married the daughter of the Tomara king Anangapala, and was bequeauthed Delhi by the Tomara king. Historian R. B. Singh speculates that it was actually Vigraharaja, who married the daughter of the Tomara king. According to Singh, Desaladevi, who has been mentioned in the play Lalita-Vigraharaja-Nataka as Vigraharaja's lover, might have been the daughter of a Tomara king named Vasantapala.[11]

Turushkas

Several sources indicate that Vigraharaja achieved military successes against the Turushkas, the Muslim Turkic invaders. The Delhi-Shivalik pillar inscription boasts that he destroyed the mlechchhas (foreigners), and once again made Aryavarta ("the land of Aryans") what its name signifies. The Prabandha-Kosha describes him as "the conqueror of Muslims". The Muslim invaders forced to retreat by him were probably the Ghaznavid rulers Bahram Shah and Khusrau-Shah.[14]

The plot of Lalita Vigraharaja Nataka involves Vigraharaja's preparations against a Turushka ruler named Hammira (Emir). In the story, his minister Shridhara tells him not to risk a battle with a powerful adversary. Nevertheless, Vigraharaja is determined to fight the Turushka king. He sends a message to his lover Desaladevi, informing her that the upcoming battle would soon give him an opportunity to meet her. The play describes Desaladevi as the daughter of prince Vasantapala of Indrapura.[15] The play is available only in fragments, so the details of the ensuing battle are not known. Historian Dasharatha Sharma identified Hammira with Khusrau Shah, and assumed that Vigraharaja repulsed his invasion.[12]

Historian R. B. Singh, on the other hand, theorizes that no actual battle place between Vigraharaja and Hammira. According to Singh's theory, the "Hammira" on the play might have been Bahram Shah, who fled to India after the Ghurids defeated him at the Battle of Ghazni (1151). Bahram Shah invaded the Tomara territory of Delhi after coming to India. Vasantapala might have been a Tomara ruler, possibly Anangapala. Indrapura may refer to Indraprastha, that is, Delhi. Vigraharaja probably decided to send an army in support of the Tomara king. But before an actual battle could take place, Bahram Shah returned to Ghazna as the Ghurids had departed from that city.[16]

Other conquests

According to the Bijolia inscription, Vigraharaja also defeated the Bhadanakas.[13] The Prithviraja Vijaya claims that he conquered several hill forts.[12]

Cultural activities

Vigraharaja's Sanskrit learning centre was converted into the Adhai Din Ka Jhonpra mosque (pictured) after the Muslim conquest of Ajmer.

Vigraharaja patronized a number of scholars, and was a poet himself. Jayanaka, in his Prithviraja-Vijaya, states that when Vigraharaja died, the name kavi-bandhava ("the friend of the poets") disappeared.[17]

The king commissioned a centre of learning in Ajmer, which was later destroyed by the Ghurid invaders and converted into the Adhai Din Ka Jhonpra mosque. Several literary works were engraved on stones at this centre:[18]

- The play Lalita Vigraharaja Nataka was composed by his court poet Somadeva in his honour. Only fragments of this play were recovered from the mosque.[19]

- Fragments of the play Harikeli Nataka, authored by Vigraharaja himself, were also found inscribed on two slabs at the Adhai Din Ka Jhonpra. The play is styled after Kiratarjuniya, a work by the ancient poet Bharavi.[17]

- A Chauhan prashasti (eulogy), which is in form of a kavya (poem).[3]

- A stuti (prayer) to various Hindu deities, also in kavya form.[3]

According to Prithviraja-Viajaya, Vigraharaja commissioned as many buildings as the hill forts he captured. Most of these appear to have been destroyed or converted to Muslim structures (such as Adhai Din Ka Jhonpra) after the Muslim conquest. He established a number of towns named Visalapura ("the city of Visala") after his alternative name Visala.[20] He is also said to have commissioned a lake named Visalasara (also known as Vislya or Bisalia) in Ajmer. According to Prithviraj Raso, the king saw a beautiful spot with springs and hills while returning from a hunt. He ordered his chief minister to construct a lake at this spot.[21]

He also founded the Vigrahapura town (modern Bisalpur) on the site of an older town called Vanapura. There, he constructed the Gokarnesvara temple, now popularly known as Bisal Deoji's temple.[22]

Like his predecessors, Vigraharaja was a devout Shaivite, as indicated by his Harakeli-Nataka. He also patronzed Jain scholars, and participated in their religious ceremonies. At the request of the Jain religious teacher Dharmaghosha-Suri, he banned animal slaughter on the Ekadashi day.[20]

The Bijolia rock inscription describes Vigraharaja as "a protector of the needy and the distressed".[4] He was succeeded by his son Amaragangeya.[21]

References

^ ab Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 56.

^ ab R. B. Singh 1964, p. 148.

^ abc Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 62.

^ abc R. B. Singh 1964, p. 150.

^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 57.

^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, pp. 58-59.

^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 149.

^ Shyam Singh Ratnawat & Krishna Gopal Sharma 1999, p. 105.

^ Asoke Kumar Majumdar 1956, p. 109.

^ Dasharatha Sharma 1959, pp. 57-58.

^ abc R. B. Singh 1964, p. 147.

^ abcd Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 60.

^ ab Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 59.

^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 145.

^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 143.

^ R. B. Singh 1964, pp. 143-144.

^ ab R. B. Singh 1964, p. 151.

^ R. B. Singh 1964, p. 152.

^ R. B. Singh 1964, pp. 151-152.

^ ab Dasharatha Sharma 1959, p. 64.

^ ab R. B. Singh 1964, p. 153.

^ "Bisaldeo Temple". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 29 September 2016..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Asoke Kumar Majumdar (1956). Chaulukyas of Gujarat. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. OCLC 4413150.

Dasharatha Sharma (1959). Early Chauhān Dynasties. S. Chand / Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9780842606189.

R. B. Singh (1964). History of the Chāhamānas. N. Kishore. OCLC 11038728.

Shyam Singh Ratnawat; Krishna Gopal Sharma (eds.). History and culture of Rajasthan: from earliest times upto 1956 A.D. University of Rajasthan. Centre for Rajasthan Studies. OCLC 42717862.