Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | |

|---|---|

| |

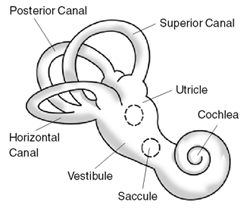

| Exterior of labyrinth of the inner ear. | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology |

| Symptoms | Repeated periods of a spinning sensation with movement[1] |

| Usual onset | 50s to 70s old[2] |

| Duration | Episodes less than a minute[3] |

| Risk factors | Older age, minor head injury[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Positive Dix–Hallpike test after other possible causes have been ruled out[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Labyrinthitis, Ménière's disease, stroke, vestibular migraine[3][4] |

| Treatment | Epley maneuver or Brandt–Daroff exercises[3][5] |

| Prognosis | Resolves in 1–2 weeks[6] |

| Frequency | 2.4% affected at some point[1] |

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a disorder arising from a problem in the inner ear.[3] Symptoms are repeated, brief periods of vertigo with movement, that is, of a spinning sensation upon changes in the position of the head.[1] This can occur with turning in bed or changing position.[3] Each episode of vertigo typically lasts less than one minute.[3]Nausea is commonly associated.[6] BPPV is one of the most common causes of vertigo.[1][2]

BPPV can result from a head injury or simply occur among those who are older.[3] A specific cause is often not found.[3] The underlying mechanism involves a small calcified otolith moving around loose in the inner ear.[3] It is a type of balance disorder along with labyrinthitis and Ménière's disease.[3] Diagnosis is typically made when the Dix–Hallpike test results in nystagmus (a specific movement pattern of the eyes) and other possible causes have been ruled out.[1] In typical cases, medical imaging is not needed.[1]

BPPV is often treated with a number of simple movements such as the Epley maneuver or Brandt–Daroff exercises.[3][5] Medications may be used to help with nausea.[6] There is tentative evidence that betahistine may help with vertigo but its use is not generally needed.[1][7] BPPV is not a serious condition.[6] Typically it resolves in one to two weeks.[6] It, however, may recur in some people.[6]

The first medical description of the condition occurred in 1921 by Robert Barany.[8] About 2.4% of people are affected at some point in time.[1] Among those who live until their 80s, 10% have been affected.[2] BPPV affects females twice as often as males.[6] Onset is typically in the person's 50s to 70s.[2]

.mw-parser-output .toclimit-2 .toclevel-1 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-3 .toclevel-2 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-4 .toclevel-3 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-5 .toclevel-4 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-6 .toclevel-5 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-7 .toclevel-6 ul{display:none}

Contents

1 Signs and symptoms

2 Cause

3 Mechanism

4 Diagnosis

4.1 Differential diagnosis

5 Treatment

5.1 Repositioning maneuvers

5.1.1 Epley maneuver

5.1.2 Semont maneuver

5.1.3 Brandt–Daroff exercises

5.1.4 Roll maneuver

5.2 Medications

5.3 Surgery

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

Signs and symptoms

- Symptoms

Vomiting is common, depending on the strength of vertigo itself and the causes for this illness.

Nausea is often associated.

Paroxysmal—Sudden onset of episodes with a short duration: lasts only seconds to minutes.- Positional in onset: Can only be induced by a change in position.

Pre-syncope (feeling faint) or syncope (fainting) is unusual but possible.- Rotatory (torsional) nystagmus, where the top of the eye rotates towards the affected ear in a beating or twitching fashion, which has a latency and can be fatigued (vertigo should lessen with deliberate repetition of the provoking maneuver). Nystagmus should only last for 30 seconds to one minute.

- Visual disturbance: It may be difficult to read or see during an attack due to associated nystagmus.

Vertigo—Spinning dizziness, which must have a rotational component.

Many patients will report a history of vertigo as a result of fast head movements. Many patients are also capable of describing the exact head movements that provoke their vertigo. Purely horizontal nystagmus and symptoms of vertigo lasting more than one minute can also indicate BPPV occurring in the horizontal semicircular canal.

Patients do not experience other neurological deficits such as numbness or weakness, and if these symptoms are present, a more serious etiology, such as posterior circulation stroke or ischemia, must be considered.

The spinning sensation experienced from BPPV is usually triggered by movement of the head, will have a sudden onset, and can last anywhere from a few seconds to several minutes. The most common movements patients report triggering a spinning sensation are tilting their heads upwards in order to look at something, and rolling over in bed.[9]

Cause

Within the labyrinth of the inner ear lie collections of calcium crystals known as otoconia or otoliths. In patients with BPPV, the otoconia are dislodged from their usual position within the utricle, and migrate over time into one of the semicircular canals (the posterior canal is most commonly affected due to its anatomical position). When the head is reoriented relative to gravity, the gravity-dependent movement of the heavier otoconial debris (colloquially "ear rocks") within the affected semicircular canal causes abnormal (pathological) endolymph fluid displacement and a resultant sensation of vertigo. This more common condition is known as canalithiasis.

In rare cases, the crystals themselves can adhere to a semicircular canal cupula, rendering it heavier than the surrounding endolymph. Upon reorientation of the head relative to gravity, the cupula is weighted down by the dense particles, thereby inducing an immediate and sustained excitation of semicircular canal afferent nerves. This condition is termed cupulolithiasis.

There is evidence in the dental literature that malleting of an osteotome during closed sinus floor elevation, otherwise known as osteotome sinus elevation or lift, transmits percussive and vibratory forces capable of detaching otoliths from their normal location and thereby leading to the symptoms of BPPV.[10][11]

It can be triggered by any action which stimulates the posterior semi-circular canal including:

- Looking up or down

- Following head injury

- Sudden head movement

- Rolling over in bed

- Tilting the head

BPPV may be made worse by any number of modifiers which may vary between individuals:

- Changes in barometric pressure — patients may feel increased symptoms up to two days before rain or snow

Lack of sleep (required amounts of sleep may vary widely)- Stress

An episode of BPPV may be triggered by dehydration, such as that caused by diarrhea. For this reason, it commonly occurs in post-operative patients who have diarrhea induced by post-operative antibiotics.

BPPV is one of the most common vestibular disorders in patients presenting with dizziness; a migraine is implicated in idiopathic cases. Proposed mechanisms linking the two are genetic factors and vascular damage to the labyrinth.[12]

Although BPPV can occur at any age, it is most often seen in people over the age of 60.[13] Besides aging, there are no major risk factors known for BPPV, although previous episodes of head trauma, or the inner ear infection labyrinthitis, may predispose to the future development of BPPV.[9]

Mechanism

The inside of the ear is composed of an organ called the vestibular labyrinth. The vestibular labyrinth includes semicircular canals, which contain fluids and fine hairlike sensors which act as a monitor to the rotations of the head. An important structure in the inner ear includes the otolith organs which contain crystals that are sensitive to gravity. These crystals are responsible for sensitivity to head positions, and can also be dislocated, causing them to lodge inside one of the semicircular canals, which causes dizziness.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

The condition is diagnosed by the patient's history, and by performing the Dix–Hallpike test or the roll test, or both.[14][15]

The Dix–Hallpike test is a common test performed by examiners to determine whether the posterior semicircular canal is involved.[15] It involves a reorientation of the head to align the posterior semicircular canal (at its entrance to the ampulla) with the direction of gravity. This test will reproduce vertigo and nystagmus characteristic of posterior canal BPPV.[14]

When performing the Dix–Hallpike test, patients are lowered quickly to a supine position, with the neck extended by the clinician performing the maneuver. For some patients, this maneuver may not be indicated, and a modification may be needed that also targets the posterior semicircular canal. Such patients include those who are too anxious about eliciting the uncomfortable symptoms of vertigo and those who may not have the range of motion necessary to comfortably be in a supine position. The modification involves the patient moving from a seated position to side-lying without their head extending off the examination table, such as with Dix–Hallpike. The head is rotated 45 degrees away from the side being tested, and the eyes are examined for nystagmus. A positive test is indicated by the patient report of a reproduction of vertigo and clinician observation of nystagmus. Both the Dix–Hallpike and the side-lying testing position have yielded similar results, and as such the side-lying position can be used if the Dix–Hallpike cannot be performed easily.[16]

The roll test can determine whether the horizontal semicircular canal is involved.[14] The roll test requires the patient to be in a supine position with their head in 30° of cervical flexion. Then the examiner quickly rotates the head 90° to the left side, and checks for vertigo and nystagmus. This is followed by gently bringing the head back to the starting position. The examiner then quickly rotates the head 90° to the right side and checks again for vertigo and nystagmus.[14] In this roll test, the patient may experience vertigo and nystagmus on both sides, but rotating towards the affected side will trigger a more intense vertigo. Similarly, when the head is rotated towards the affected side, the nystagmus will beat towards the ground and be more intense.[15]

As mentioned above, both the Dix–Hallpike and roll test provoke the signs and symptoms in subjects suffering from archetypal BPPV. The signs and symptoms patients with BPPV experience are typically a short-lived vertigo and observed nystagmus. In some patients, though rarely, vertigo can persist for years. Assessment of BPPV is best done by a medical health professional skilled in the management of dizziness disorders, commonly a physiotherapist, audiologist or other physician.

The nystagmus associated with BPPV has several important characteristics which differentiate it from other types of nystagmus.

- Latency of onset: there is a 5–10 second delay prior to onset of nystagmus.

- Nystagmus lasts for 5–60 seconds.

- Positional: the nystagmus occurs only in certain positions.

- Repeated stimulation, including via Dix–Hallpike maneuvers, cause the nystagmus to fatigue or disappear temporarily.

- Rotatory/Torsional component is present, or (in the case of lateral canal involvement) the nystagmus beats in either a geotropic (towards the ground) or ageotropic (away from the ground) fashion.

- Visual fixation suppresses nystagmus due to BPPV.

Although rare, CNS disorders can sometimes present as BPPV. A practitioner should be aware that if a patient whose symptoms are consistent with BPPV, but does not show improvement or resolution after undergoing different particle repositioning maneuvers — detailed in the Treatment section below — need to have a detailed neurological assessment and imaging performed to help identify the pathological condition.[1]

Differential diagnosis

Vertigo, a distinct process sometimes confused with the broader term, dizziness, accounts for about six million clinic visits in the United States every year; between 17 and 42% of these patients are eventually diagnosed with BPPV.[1]

Other causes of vertigo include:

Motion sickness/motion intolerance: a disjunction between visual stimulation, vestibular stimulation, and/or proprioception

- Visual exposure to nearby moving objects (examples of optokinetic stimuli include passing cars and falling snow)

- Other diseases: (labyrinthitis, Ménière's disease, and migraine,[17] etc.)

Treatment

Repositioning maneuvers

A number of maneuvers have been found to be effective including: the Epley maneuver, the Semont maneuver, and to a lesser degree Brandt–Daroff exercises.[5] Both the Epley and the Semont maneuver are equally effective.[5]

Epley maneuver

The Epley maneuver employs gravity to move the calcium crystal build-up that causes the condition.[18] This maneuver can be performed during a clinic visit by health professionals, or taught to patients to practice at home, or both.[19] Postural restriction after the Epley maneuver increases its effect somewhat.[20]

When practiced at home, the Epley maneuver is more effective than the Semont maneuver. The most effective repositioning treatment for posterior canal BPPV is the therapist-performed Epley combined with home-practiced Epley maneuvers.[21] Devices like the DizzyFIX can help users conduct the Epley maneuver at home, and are available for the treatment of BPPV.[22]

The Epley maneuver does not address the actual presence of the particles (otoconia); rather it changes their location. The maneuver aims to move these particles from some locations in the inner ear which cause symptoms such as vertigo, and reposition them to where they do not cause these problems.

Semont maneuver

The Semont maneuver has a cure rate of 90.3%.[23] It is performed as follows:

- The patient is seated on a treatment table with their legs hanging off the side of the table. The therapist then turns the patient's head towards the unaffected side 45 degrees.

- The therapist then quickly tilts the patient so they are lying on the affected side. The head position is maintained, so their head is turned up 45 degrees. This position is maintained for 3 minutes. The purpose is to allow the debris to move to the apex of the ear canal.

- The patient is then quickly moved so they are lying on the unaffected side with their head in the same position (now facing downwards 45 degrees). This position is also held for 3 minutes. The purpose of this position is to allow the debris to move toward the exit of the ear canal.

- Finally, the patient is slowly brought back to an upright seated position. The debris should then fall into the utricle of the canal and the symptoms of vertigo should decrease or end completely.

Some patients will only need one treatment, but others may need multiple treatments, depending on the severity of their BPPV. In the Semont maneuver, as with the Epley maneuver, patients themselves are able to achieve canalith repositioning.[19]

Brandt–Daroff exercises

The Brandt–Daroff exercises may be prescribed by the clinician as a home treatment method, usually in conjunction with particle-repositioning maneuvers or in lieu of the particle-repositioning maneuver. The exercise is a form of habituation exercise, designed to allow the patient to become accustomed to the position which causes the vertigo symptoms. The Brandt–Daroff exercises are performed in a similar fashion to the Semont maneuver; however, as the patient rolls onto the unaffected side, the head is rotated toward the affected side.[24] The exercise is typically performed 3 times a day with 5–10 repetitions each time, until symptoms of vertigo have resolved for at least 2 days.[14]

Roll maneuver

For the lateral (horizontal) canal, a separate maneuver has been used for productive results. It is unusual for the lateral canal to respond to the canalith repositioning procedure used for the posterior canal BPPV. Treatment is therefore geared towards moving the canalith from the lateral canal into the vestibule.[25]

The roll maneuver or its variations are used, and involve rolling the patient 360 degrees in a series of steps to reposition the particles.[1] This maneuver is generally performed by a trained clinician who begins seated at the head of the examination table with the patient supine[26] There are four stages, each a minute apart, and at the third position the horizontal canal is oriented in a vertical position with the patient's neck flexed and on forearm and elbows.[26] When all four stages are completed, the head roll test is repeated, and if negative, treatment ceases.[26]

Medications

Medical treatment with anti-vertigo medications may be considered in acute, severe exacerbation of BPPV, but in most cases are not indicated. These primarily include drugs of the anti-histamine and anti-cholinergic class, such as meclizine and hyoscine butylbromide (scopolamine), respectively. The medical management of vestibular syndromes has become increasingly popular over the last decade, and numerous novel drug therapies (including existing drugs with new indications) have emerged for the treatment of vertigo/dizziness syndromes. These drugs vary considerably in their mechanisms of action, with many of them being receptor- or ion channel-specific. Among them are betahistine or dexamethasone/gentamicin for the treatment of Ménière's disease, carbamazepine/oxcarbazepine for the treatment of paroxysmal dysarthria and ataxia in multiple sclerosis, metoprolol/topiramate or valproic acid/tricyclic antidepressant for the treatment of vestibular migraine, and 4-aminopyridine for the treatment of episodic ataxia type 2 and both downbeat and upbeat nystagmus.[27] These drug therapies offer symptomatic treatment, and do not affect the disease process or resolution rate. Medications may be used to suppress symptoms during the positioning maneuvers if the patient's symptoms are severe and intolerable. More dose-specific studies are required, however, in order to determine the most effective drug(s) for both acute symptom relief and long-term remission of the condition.[27]

Surgery

Surgical treatments, such as a semi-circular canal occlusion, do exist for BPPV, but carry the same risk as any neurosurgical procedure. Surgery is reserved as a last resort option for severe and persistent cases which fail vestibular rehabilitation (including particle repositioning and habituation therapy).

References

^ abcdefghijkl Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvidas L, Barrs D, Bronston LJ, Cass S, Chalian AA, Desmond AL, Earll JM, Fife TD, Fuller DC, Judge JO, Mann NR, Rosenfeld RM, Schuring LT, Steiner RW, Whitney SL, Haidari J (November 2008). "Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo". Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery. 139 (5 Suppl 4): S47–81. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.08.022. PMID 18973840. Lay summary – AAO-HNS (2008-11-01)..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcd Dickson, Gretchen (2014). Primary Care ENT, An Issue of Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, Volume 41, Issue 1 of The Clinics: Internal Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 115. ISBN 9780323287173. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

^ abcdefghijkl "Balance Disorders". NIDCD. August 10, 2015. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

^ Ferri, Fred F. (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 170. ISBN 9780323448383. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

^ abcd Hilton MP, Pinder DK (December 2014). "The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD003162. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003162.pub3. PMID 25485940.

^ abcdefg "Positional vertigo: Overview". PubMed Health. 30 January 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

^ Murdin L, Hussain K, Schilder AG (June 2016). "Betahistine for symptoms of vertigo". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD010696. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010696.pub2. PMID 27327415.

^ Daroff, Robert B. (2012). "Chapter 37". Bradley's neurology in clinical practice (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 9781455728077. Archived from the original on 2016-12-21.

^ ab "Benign positional vertigo". A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

^ Sammartino G, Mariniello M, Scaravilli MS (June 2011). "Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo following closed sinus floor elevation procedure: mallet osteotomes vs. screwable osteotomes. A triple blind randomized controlled trial". Clinical Oral Implants Research. 22 (6): 669–72. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.01998.x. PMID 21054553.

^ Kim MS, Lee JK, Chang BS, Um HS (April 2010). "Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo as a complication of sinus floor elevation". Journal of Periodontal & Implant Science. 40 (2): 86–9. doi:10.5051/jpis.2010.40.2.86. PMC 2872812. PMID 20498765.

^ Lempert T, Neuhauser H (March 2009). "Epidemiology of vertigo, migraine and vestibular migraine". Journal of Neurology. 256 (3): 333–8. doi:10.1007/s00415-009-0149-2. PMID 19225823.

^ Mayo Clinic Staff (July 10, 2012). "Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)". Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

^ abcde Schubert, Michael C. (2019-01-25). "Vestibular Disorders". In O'Sullivan, Susan B.; Schmitz, Thomas J.; Fulk, George D. Physical Rehabilitation (7th ed.). pp. 918–49. ISBN 978-0-8036-9464-4.

^ abc Korres SG, Balatsouras DG (October 2004). "Diagnostic, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic aspects of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo". Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery. 131 (4): 438–44. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.046. PMID 15467614.

^ Cohen HS (March 2004). "Side-lying as an alternative to the Dix-Hallpike test of the posterior canal". Otology & Neurotology. 25 (2): 130–4. doi:10.1097/00129492-200403000-00008. PMID 15021771.

^ Buchholz, D. Heal Your Headache. New York:Workman Publishing;2002:74-75

^ von Brevern M, Seelig T, Radtke A, Tiel-Wilck K, Neuhauser H, Lempert T (August 2006). "Short-term efficacy of Epley's manoeuvre: a double-blind randomised trial". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 77 (8): 980–2. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2005.085894. PMC 2077628. PMID 16549410.

^ ab Radtke A, von Brevern M, Tiel-Wilck K, Mainz-Perchalla A, Neuhauser H, Lempert T (July 2004). "Self-treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Semont maneuver vs Epley procedure". Neurology. 63 (1): 150–2. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000130250.62842.C9. PMID 15249626.

^ Hunt WT, Zimmermann EF, Hilton MP (April 2012). "Modifications of the Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD008675. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008675.pub2. PMID 22513962.

^ Helminski JO, Zee DS, Janssen I, Hain TC (May 2010). "Effectiveness of particle repositioning maneuvers in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a systematic review". Physical Therapy. 90 (5): 663–78. doi:10.2522/ptj.20090071. PMID 20338918.

^ Beyea JA, Wong E, Bromwich M, Weston WW, Fung K (January 2008). "Evaluation of a particle repositioning maneuver Web-based teaching module". The Laryngoscope. 118 (1): 175–80. doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e31814b290d. PMID 18251035.

^ Chen Y, Zhuang J, Zhang L, Li Y, Jin Z, Zhao Z, Zhao Y, Zhou H (September 2012). "Short-term efficacy of Semont maneuver for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a double-blind randomized trial". Otology & Neurotology. 33 (7): 1127–30. doi:10.1097/mao.0b013e31826352ca. PMID 22892804.

^ Vesely DL, Chiou S, Douglass MA, McCormick MT, Rodriguez-Paz G, Schocken DD (March 1996). "Atrial natriuretic peptides negatively and positively modulate circulating endothelin in humans". Metabolism. 45 (3): 315–9. doi:10.1016/S0026-0495(96)90284-X. PMID 8606637.

^ Hegemann SC, Palla A (August 2010). "New methods for diagnosis and treatment of vestibular diseases". F1000 Medicine Reports. 2: 60. doi:10.3410/M2-60. PMC 2990630. PMID 21173877.

^ abc Hornibrook J (2011). "Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): History, Pathophysiology, Office Treatment and Future Directions". International Journal of Otolaryngology. 2011: 835671. doi:10.1155/2011/835671. PMC 3144715. PMID 21808648.

^ ab Huppert D, Strupp M, Mückter H, Brandt T (March 2011). "Which medication do I need to manage dizzy patients?". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 131 (3): 228–41. doi:10.3109/00016489.2010.531052. PMID 21142898.

Further reading

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Parnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J (September 2003). "Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)". Cmaj. 169 (7): 681–93. PMC 202288. PMID 14517129.

Huppert D, Strupp M, Mückter H, Brandt T (March 2011). "Which medication do I need to manage dizzy patients?". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 131 (3): 228–41. doi:10.3109/00016489.2010.531052. PMID 21142898.

Solomon D (September 2000). "Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo" (PDF). Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 2 (5): 417–428. doi:10.1007/s11940-000-0040-z. PMID 11096767.

"Videos". Neurology. 2018-12-30. in Radtke A, von Brevern M, Tiel-Wilck K, Mainz-Perchalla A, Neuhauser H, Lempert T (July 2004). "Self-treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Semont maneuver vs Epley procedure". Neurology. 63 (1): 150–2. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000130250.62842.C9. PMID 15249626.

External links

| Classification | D

|

|---|---|

| External resources |

|