Hungarian occupation of Yugoslav territories

Hungarian occupation of Yugoslav territories | |

|---|---|

Part of Yugoslavia occupied then annexed by Hungary | |

Occupation and partition of Yugoslavia in 1941. The Hungarian-occupied then annexed areas of Yugoslavia are shown in pale orange in the north (Bačka and Baranja) and northwest (Međimurje and Prekmurje). | |

| Country | |

| Occupied by Hungary | 11 April 1941 |

| Annexed by Hungary | 14 December 1941 |

| Occupied by Germany | 15 March 1944 |

| Territories | Region

|

| Government | |

| • Type | incorporated into existing Hungarian counties |

| • Body | Bács-Bodrog, Baranya, Zala, Vas |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11,475 km2 (4,431 sq mi) |

| Population (1941) | |

| • Total | c.1,145,000 |

| See Demographics section | |

The Hungarian occupation of Yugoslav territories consisted of the military occupation, then annexation, of the Bačka, Baranja, Međimurje and Prekmurje regions of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Kingdom of Hungary during World War II. These territories had all been under Hungarian rule prior to 1920, and had been transferred to Yugoslavia as part of the post-World War I Treaty of Trianon. They now form part of several states: Yugoslav Bačka is now part of Vojvodina, an autonomous province of Serbia, Yugoslav Baranja and Međimurje are part of modern-day Croatia, and Yugoslav Prekmurje is part of modern-day Slovenia. The occupation began on 11 April 1941 when 80,000 Hungarian troops crossed the Yugoslav border in support of the German-led Axis invasion of Yugoslavia that had commenced five days earlier. There was some resistance to the Hungarian forces from Serb Chetnik irregulars, but the defences of the Royal Yugoslav Army had collapsed by this time. The Hungarian forces were indirectly aided by the local Volksdeutsche, the German minority, which had formed a militia and disarmed around 90,000 Yugoslav troops. Despite only sporadic resistance, Hungarian troops killed many civilians during these initial operations, including some Volksdeutsche. The government of the newly formed Axis puppet state, the Independent State of Croatia, subsequently consented to the Hungarian annexation of the Međimurje area, which dismayed the Croat population of the region.

The occupation authorities immediately classified the population of Bačka and Baranja into those that had lived in those regions when they had last been under Hungarian rule in 1920 and the mostly Serb settlers who had arrived since the areas had been part of Yugoslavia. They then began herding thousands of local Serbs into concentration camps and expelled them to the Independent State of Croatia, Italian-occupied Montenegro, and the German-occupied territory of Serbia. Ultimately, tens of thousands of Serbs were deported from the occupied territories. This was followed by the implementation of a policy of "magyarisation" of the political, social and economic life of the occupied territories, which included the re-settlement of Hungarians and Székelys from other parts of Hungary. "Magyarisation" did not impact the Volksdeutsche, who received special status under Hungarian rule, and in Prekmurje the Hungarian authorities were more permissive towards ethnic Slovenes.

Small-scale armed resistance to the Hungarian occupation commenced in the latter half of 1941 and was answered with harsh measures, including summary executions, expulsions and internment. The insurgency was mainly concentrated in the ethnic-Serb area of southern Bačka in the Šajkaška region, where Hungarian forces avenged their losses. In August 1941 a civilian administration took over the government of the "Recovered Southern Territories" (Hungarian: Délvidék), and they were formally annexed to Hungary in December. In January 1942 the Hungarian military conducted raids during which they killed over 3,300 people, mostly Serbs and Jews.

In March 1944, when Hungary realised that it was on the losing side in the war and began to negotiate with the Allies, Germany took control of the country, including the annexed territories, during Operation Margarethe I. This was followed by the collection and transport of the remaining Jews in the occupied territories to extermination camps, resulting in the deaths of 85 per cent of the Jews in the occupied territories. Prior to their withdrawal from the Balkans in the face of the advance of the Soviet Red Army, the Germans evacuated 60,000–70,000 Volksdeutsche from Bačka and Baranja to Austria. Bačka and Baranja were restored to Yugoslav control when the Germans were pushed out of the region by the Red Army in late 1944. Međimurje and Prekmurje remained occupied until the last weeks of the war.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Demographics

1.2 Developments 1938–1941

2 Invasion

3 Geography

4 Administration

5 Districts

6 The Holocaust

7 Resistance and repression

8 Aftermath

8.1 German occupation and the Holocaust

8.2 Flight of the Volksdeutsche and Yugoslav military control

8.3 Return to Yugoslav civilian control

8.4 Prosecutions

8.5 Demographic and political changes

8.6 Formal apologies

9 See also

10 Footnotes

11 References

11.1 Books

11.2 Journals

11.3 Websites

Background

Map showing the difference between the borders of Hungary before and after the Treaty of Trianon. The old Kingdom of Hungary is in green, autonomous Croatia-Slavonia in grey. The population charts are based on the 1910 Hungarian census.

At the Paris Peace Conference following the conclusion of World War I, the Entente Powers signed the Treaty of Trianon with Hungary after the breakup of Austria-Hungary. Among other things, the treaty defined the border between Hungary and the newly created Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (KSCS, renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929). It divided the previously Hungarian-ruled regions of Banat, Bačka and Baranja between Hungary, the KSCS, and Romania, and transferred the Međimurje region and about two thirds of the Prekmurje region from Hungary to the KSCS. Sizable numbers of Hungarians and Volksdeutsche remained in the areas incorporated into the KSCS.[2][3] Between 1918 and 1924, 44,903 Hungarians (including 8,511 government employees) were deported to Hungary from the territories transferred to Yugoslavia, and approximately 10,000 Yugoslav military settlers (Serbo-Croatian: Solunski dobrovoljci, lit. Salonika volunteers), mainly Serbs, were settled in Bačka and Baranja by the Yugoslav government.[4][5] During the interwar period Hungary agitated for a revision of the borders agreed in the Treaty of Trianon, and relations between the two countries were difficult.[2][3] On 22 August 1938, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia agreed to a revision of Trianon that allowed Hungary to re-arm itself.[6]

Demographics

Prior to the occupation, the most recent Yugoslav census had been taken in 1931. This census used language as the primary criterion, and counted all speakers of Serbo-Croatian as one group, rather than recognising distinct Serb, Croat, Bosnian Muslim, Macedonian and Montenegrin nationalities.[7] Aligning data on religious affiliation with the linguistic data has been used by scholars to determine approximate numbers of Serbs and Croats in the 1931 census, by counting those of the Roman Catholic denomination as Croats.[8]

According to the 1931 census, the territories of Bačka and Baranja had a combined population of 837,742. This included between 275,014 and 283,114 Hungarians, and between 185,458 and 194,908 Volksdeutsche. Hungarians therefore made up around one-third of the population of these territories, with the Volksdeutsche comprising slightly less than one-quarter.[9][10] According to the historian Dr. Krisztián Ungváry, the 1931 census showed that the population of Bačka and Baranja included 150,301 Serbs and 3,099 Croats. This corresponds to a Serb population of about 18 per cent.[10] These figures vary considerably from the combined Serb and Croat population of 305,917 provided by Professor Jozo Tomasevich, corresponding to 36.5 per cent of the population.[11] The 1931 census figures for Međimurje and Prekmurje show a total population of 193,640, of which 101,467 (52.2 per cent) were Croats, 75,064 (38.7 per cent) were Slovenes, and 15,308 (8 per cent) were Hungarians.[10]

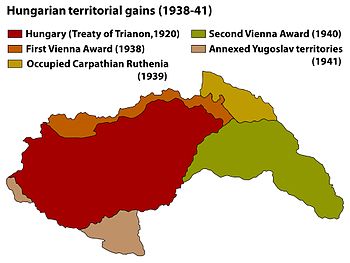

The territorial gains of Hungary in 1938–41. The occupied then annexed areas of Yugoslavia are shown in tan in the south (Bačka and Baranja) and west (Međimurje and Prekmurje).

Developments 1938–1941

Between 1938 and 1940, following German–Italian mediation in the First and Second Vienna Awards, and the Hungarian invasion of Carpatho-Ukraine, Hungary enlarged its territory. It absorbed parts of southern Czechoslovakia, Carpathian Ruthenia and the northern part of Transylvania, which the Kingdom of Romania ceded. One of the ethno-cultural areas that changed hands between Romania and Hungary at this time was the Székely Land. The support that Hungary received from Germany for these border revisions meant that the relationship between the two countries became even closer. On 20 November 1940, Hungary formally joined the Axis Tripartite Pact.[12] On 12 December 1940, at the initiative of the Prime Minister, Count Pál Teleki, Hungary concluded a friendship and non-aggression treaty with Yugoslavia. Although the concept had received support from both Germany and Italy, the actual signing of the treaty did not, as Germany's planned invasion of Greece would be simplified if Yugoslavia could be neutralised.[13] After the Yugoslav military coup of 27 March 1941, when the Germans asked the Hungarian Regent, Miklós Horthy, for clearance to launch one of their armoured thrusts using Hungarian territory, Teleki was unable to dissuade the Regent. Concluding that Hungary had disgraced itself irrevocably by siding with the Germans against the Yugoslavs, Teleki shot himself.[14][15] Horthy informed Hitler that evening that Hungary would abide by the friendship treaty with Yugoslavia, though it would likely cease to apply should Croatia secede and Yugoslavia cease to exist.[16]

Invasion

On 10 April 1941, the Independent State of Croatia (Croatian: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH) was established in Zagreb by the Ustaše. That day Horthy and the new Prime Minister of Hungary László Bárdossy issued a joint declaration that Yugoslavia had ceased to exist, releasing Hungary from its obligations under the non-aggression pact and the Treaty of Trianon.[16] According to the declaration Hungarian troops would act to "protect the Hungarians who live in the south parts from the anarchy" of the April War which had begun there several days earlier when Italian and German troops invaded.[17][18][19] The following day the Hungarian 3rd Army began occupying those regions of Yugoslavia using the Mobile, IV and V Corps, with I and VII Corps in reserve.[20][21][22][23] That day (11 April), the headquarters of the 3rd Army informed that of the German 2nd Army that Hungarian forces had crossed the frontier north of Osijek and near Subotica.[24]

The German army's rapid manoeuvres during the invasion had forced the tactical withdrawal of Yugoslav forces facing Hungarian army units and there was no significant fighting between the two armies. The Hungarian forces advanced south to the Danube between Vukovar and the confluence with the Tisza without any real military resistance.[25]Serb Chetnik irregulars fought isolated engagements,[23] and the Hungarian General Staff considered irregular resistance forces to be their only significant opposition.[26][27]

On 12 April, the Hungarian 1st Parachute Battalion captured canal bridges at Vrbas and Srbobran. Meanwhile, Sombor was captured against determined Chetnik resistance, and Subotica was also captured.[23] This, the first airborne operation in Hungarian history, was not without incident. The battalion's aircraft consisted of five Italian-made Savoia-Marchetti SM.75 transport aircraft formerly with the civilian airline MALERT, but pressed into service with the Royal Hungarian Air Force (Hungarian: Magyar Királyi Honvéd Légierő, MKHL) at the start of the European war.[28] Shortly after takeoff from the airport at Veszprém-Jutas on the afternoon of 12 April, the command plane, code E-101, crashed with the loss of 20[29] or 23 lives, including 19 paratroopers. This was the heaviest single loss suffered by the Hungarians during the Yugoslav campaign.[28]

On 13 April, the 1st and 2nd Motorized Brigades occupied Novi Sad, then pushed south across the Danube into the northern part of Croatian Syrmia capturing Vinkovci and Vukovar on 18 April. These brigades then drove southeast to capture the western Serbian town of Valjevo a day later. Other Hungarian forces occupied the Yugoslavian regions of Prekmurje and Međimurje.[23] A later American assessment concluded that German forces had to take the brunt of the fighting, observing that Hungarian forces had "displayed great reluctance to attack until the enemy had been soundly beaten and thoroughly disorganized by the Germans."[30] When a Yugoslav delegation signed an armistice with German and Italian representatives at Belgrade on 17 April, the Hungarians were represented by a liaison officer, but he did not sign the document because Hungary was "not at war with Yugoslavia."[31] The armistice came into effect at noon the next day. News of the success of the Hungarian armed forces in Yugoslavia was welcomed in the Hungarian Parliament.[12] German forces occupied a narrow slice of northeastern Prekmurje along the German–Yugoslav border,[32] which included four Volksdeutsche villages. In mid-June 1941, this area was absorbed into Reichsgau Steiermark.[33]

Hungarian troops suffered 126 dead and 241 wounded during the sporadic fighting,[34] and killed between 1,122 and 3,500 civilians, including some Volksdeutsche.[18][25][35] Many civilians were arrested and tortured.[36] On 14 April 1941, around 500 Jews and Serbs were bayoneted to death, probably as a warning to others not to resist.[36] During post-war questioning, Horthy insisted that he had not wished to invade Yugoslavia, but that he had been compelled to act by disorder and the massacre of Hungarians in Bačka, but these claims have been dismissed by Tomasevich.[25]

Geography

Map showing the division of the areas of Yugoslavia occupied then annexed by Hungary, including the relevant Hungarian administrative subdivisions

The Hungarian-occupied territory of Bačka consisted of that part of the Danube Banovina bounded by the former Hungarian–Yugoslav border to the north, the Danube to the south and west, and the Tisza to the east. The occupied territory of Baranja had also been part of the Danube Banovina, but was that area bounded by the former Hungarian-Yugoslav border to the north and west, the Drava to the west and south, and the Danube to the east. The territory of Međimurje was part of the Banovina of Croatia prior to the invasion, and was bounded by the Mura river to the north and the Drava river to the south. Prekmurje consisted of that part of the pre-war Drava Banovina that lay north of the Mura.[37] Most of the Hungarian-occupied territories consisted of flat, largely agricultural land of the Pannonian Plain, except for some hilly country in the northwest of the Međimurje region and in the north of the Prekmurje region.[38] The total area of the Yugoslav territories occupied by Hungary was 11,475 square kilometres (4,431 sq mi), consisting of 8,558 km2 (3,304 sq mi) in Bačka, 1,213 km2 (468 sq mi) in Baranja, and 1,704 km2 (658 sq mi) in the Međimurje and Prekmurje regions.[10]

Administration

At first, the occupied territories were placed under military administration.[11] The international legal scholar, Professor Raphael Lemkin, who coined the word "genocide" as meaning the "destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group",[39] described the policies implemented by the Hungarian authorities in the occupied territories as "genocidal".[40] Lemkin asserted that "genocidal" policies were those that were aimed at destroying the political, social, cultural, religious, and economic existence and language of those living in occupied territories.[39] In the first two weeks of Hungarian rule, 10,000 Serbs were expelled to the German-occupied territory of Serbia, the NDH, or Italian-ruled Montenegro. On 1 May 1941, the Germans estimated that the population of the territories occupied by Hungary was 1,145,000.[41] On 9 July 1941, the military governor of the town of Čakovec in Međimurje, Colonel Zsigmond Timár, issued a declaration that the following day Međimurje was to be placed permanently under military administration and Hungarian rule.[42] According to Professor Sabrina Ramet, the government of the NDH consented to Hungarian annexation of the Međimurje area on 10 July,[43] but according to Davor Kovačić and Marica Karakaš Obradov of the Croatian Institute of History, the Hungarian declaration was made without consulting with the NDH government, and was never recognised by it.[44][45] The Croat population of the region were unhappy with the decision,[46] and military rule remained in place until 16 August 1941, after which civil administration was introduced.[47] On 12 July, the Yugoslav dinar ceased to be legal tender in the occupied territories, and was replaced by the Hungarian pengő.[48] A census of the occupied Yugoslav territories was conducted by the Hungarian authorities in 1941, which counted a total population of 1,030,027. In this census, the ethnic proportions in these territories combined were 37 per cent Hungarian, 19 per cent Volksdeutsche, 18 per cent Croats and 16 per cent Serbs,[47] and the population of Prekmurje was 102,867.[49]

On 14 December, these regions, referred to by Hungary as the "Recovered Southern Territories" (Hungarian: Délvidék),[1] were formally incorporated into Hungary and were given full representation in the Hungarian Parliament,[11] although representatives were to be nominated by the Parliament rather than elected.[50] Although plans to deport 150,000 Serbs (including colonists from the interwar period, but also native inhabitants) to the German-occupied territory of Serbia were opposed by the German command in Belgrade, the Hungarian occupational regime managed to expel between 25,000 and 60,000 of them, mostly to Serbia.[11][51][52][53] During the war, the Hungarian government resettled some of its pre-war population in Bačka and Baranja, primarily Székelys from areas of Transylvania ceded to Hungary by Romania in 1940. Between 15,000 and 18,000 were reportedly resettled in Bačka and Baranja.[54][55][56]

The Hungarian authorities established concentration camps for Serbs from which they were eventually expelled to the German-occupied territory of Serbia. As part of the "systematic magyarisation" of these territories,[57] Hungarian political parties and patriotic organisations were encouraged to be active in Bačka and Baranja, which resulted in discrimination against "less-desirable elements" of the population such as Serbs, Croats and Jews.[57] Discrimination extended to education and communication, where Hungarian and German were the only languages permitted in almost all secondary schools, and books, newspapers and periodicals in the Serbo-Croat language were virtually banned. Well-educated Serbs and Croats were precluded from undertaking work commensurate with their education.[55] Despite this, Serbs and Croats that had lived in the territories prior to 1918 retained their citizenship rights as Hungarians, and some lower-level non-Hungarian public employees were retained in their jobs. One former Serb senator and one former Croat parliamentary deputy sat in the Hungarian Parliament.[51] In Prekmurje, the Hungarian authorities were more permissive, making no attempt to deport Slovenes in large numbers, and allowing the Slovene language to be used in public.[58] Likewise, the Hungarians curried favour with the Bunjevci minority in order to persuade them that they were neither Serbs nor Croats, nor even Slavs at all: they were "Hungarians of Bunyevac mother-tongue".[59]

The Volksdeutsche of the occupied territories were an important part of the economies of the occupied territories, and by 1941, they were entirely in the thrall of the Nazi Party. Relations between the occupation authorities and the Volksdeutsche were strained by the killing of ethnic Germans during the invasion, to the extent that Adolf Hitler became aware of the issue. The Volksdeutsche were not active in the Hungarian military or civil administration, but were represented in the Hungarian Parliament, and from 1942 were permitted to conscript their members into the Wehrmacht. The official organisation of the Volksdeutsche in Hungary, the Volksbund der Deutschen in Ungarn (National League of Germans in Hungary), was essentially autonomous during the war, including within the occupied territories.[60]

Districts

Bačka and Baranja had both been part of the Danube Banovina of Yugoslavia before the war. Međimurje had been part of the Banovina of Croatia, and Prekmurje had been part of the Drava Banovina.[61] The Hungarian authorities referred to the occupied territories by the following names: Bácska for Bačka, Baranya for Baranja, Muraköz for Međimurje, and Muravidék for Prekmurje.[62] Following the occupation, the Hungarian authorities divided the occupied territories between the counties that corresponded with the administrative divisions that had existed when the area had formed part of the Kingdom of Hungary prior to 1920. These were the Bács-Bodrog, Baranya, Vas and Zala Counties. The officials in these territories were appointed rather than elected. The counties were further divided into districts, and the authorities reverted many districts, cities and towns to the names used prior to 1920, and in some cases to names which had no historical precedent. Some examples of the name changes in each county are shown below:[61]

Bács-Bodrog County:

| Baranya County:

Vas County:

| Zala County:

|

The Holocaust

In April 1941, about 23 per cent of Yugoslav Jews (about 16,680 people) lived in the territories occupied by Hungary. These included around 15,405 in Bačka and Baranja, about 425 in Međimurje, and approximately 850 in Prekmurje.[63]

The Hungarian government had passed anti-Semitic laws in 1939, and these were applied to the occupied and annexed territories. Initially the laws were applied selectively due to the transfer of the territories from military to civilian administration. Some Jews that had settled in the occupied territories were sent to the German-occupied territory of Serbia where they were placed in the Banjica concentration camp in Belgrade and subsequently killed. Others were expelled to the NDH where they met the same fate, but it is unknown how many deported Jews died in this way. After the violence of the initial occupation, no further massacres of Jews occurred during the remainder of 1941.[36]

The Jews of the occupied territories were subjected to forced labour by the Hungarian authorities, with about 4,000 Bačka and Baranja Jews being sent to hard labour camps within Hungary, 1,500 Bačka Jews being among the 10,000 Hungarian Jews sent to perform labour tasks for the Hungarian Army on the Eastern Front in September 1942, and about 600 Bačka Jews sent to work in the Bor copper mine in the German-occupied territory of Serbia in July 1943. Only 2 per cent of those sent to the Eastern Front survived the war.[64]

Resistance and repression

In Bačka and Baranja, the Volksdeutsche and Hungarian authorities killed significant numbers of Serbs.[65] After small-scale armed resistance broke out in Hungarian-occupied Bačka and Baranja in the second half of 1941, the Hungarian military reacted with heavy repressive measures.[60] In September 1941 alone the Hungarian occupation forces summarily executed 313 people.[35] Measures included the establishment of temporary concentration camps at Ada, Bačka Topola, Begeč, Odžaci, Bečej and Subotica, as well as at Novi Sad, Pechuj and Baja. According to Professor Paul Mojzes, some 2,000 Jews and a large number of Serbs were detained in these camps for periods from two weeks to two months, with Jews that had not been interned being employed as forced labourers.[36] Several thousand people remained in camps until the end of the war.[53] Some of the Jews that had migrated to Bačka and Baranja during the inter-war period were expelled to the NDH or the German-occupied territory of Serbia where they were killed.[36] The communist-led Partisan resistance movement of Josip Broz Tito was never strong in Bačka and Baranja because the flat terrain of the region did not lend itself to guerilla warfare, and because South Slavs, from which the Partisans drew their recruits, only made up one-third of the regional population. Some Partisan units raised in the occupied territories were sent to the NDH to reinforce Partisan formations operating there. Despite their initial resistance, the Chetnik movement was largely inactive during the occupation, maintaining some covert activity only.[38] The Partisans and their regional committee had largely been destroyed by the end of 1941.[66]

In January 1942, the Hungarian army and gendarmerie undertook a major raid in southern Bačka, during which they massacred 2,550 Serbs, 743 Jews and 47 other people[67] in places such as Bečej, Srbobran and Novi Sad,[60][68] under the pretext that they were searching for Partisans.[69] Other sources place the number of Serbs and Jews massacred in Novi Sad as being much lower, at around 879.[70] Raids were carried out in Šajkaš (Sajkásvidék) over 4–19 January; in Novi Sad (Újvidék) over 21–23 January; and in Bečej (Óbecse) over 25–29 January. Over the period 4–24 January, massacres were carried out by the Hungarian 15th Light Division commanded by Major General József Grassy and units of the Royal Gendarmerie. The operations were ordered by Grassy, Lieutenant General Ferenc Feketehalmy-Czeydner, Colonel László Deák,[23] and Royal Gendarmerie Captain Dr. Márton Zöldi.[71] In addition to Serbs and Jews, members of other ethnicities were also victims: Roma people, a small number of Russian refugees who had fled Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution, and some local Hungarians.[72] In mid-1942, the Yugoslav government-in-exile reported that churches had been looted and destroyed, and that Serbian Orthodox holy days had been prohibited by the Hungarian administration. These reports stated that the a camp in Novi Sad held 13,000 Serb and Jewish men, women and children.[48]

Under pressure from the Hungarian political opposition, the Hungarian government charged 14 Hungarian officers with high treason in relation to the massacres, including Feketehalmy-Czeydner, Grassy, Deák and Zöldi. A military trial was held in Budapest between 23 December 1943 and January 1944, and those that were convicted were sentenced to between 10 and 15 years imprisonment for their part in the massacres. Feketehalmy-Czeydner, Grassy, Deák and Zöldi were not sentenced as they could not be located, and had fled to Germany.[73] It is apparent from the trial proceedings that Zöldi was present during some of the trial.[74] Professor Lajčo Klajn has stated that those most responsible for the massacre were not tried before this military court, and that they included Prime Minister Bárdossy and the Minister for Interior Affairs Dr. Ferenc Keresztes-Fischer, both of whom appeared only as witnesses. Klajn also states that the Chief of the General Staff, Ferenc Szombathelyi and the Minister of Defence should also have been examined by the court,[75] that the "genocide had been planned by the highest military and political circles in Hungary for a long time in advance",[76] and had been intended to convince the German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop that Hungarian troops were needed on its territory instead of the Eastern Front.[77] In mid-1944, Partisan activity increased in Bačka to such an extent that special regulations similar to the "Special Administrative Regulations" that applied to the operational zones of the Hungarian Army were extended to Bačka: curfews were imposed and political activities were forbidden. A self-defence organization, the Pandurs, was created.[78]

Aftermath

German occupation and the Holocaust

Monument to the 1942 raid victims in Novi Sad.

The occupation of Bačka and Baranja lasted until 1944. Fearing that Hungary might conclude a separate peace with the Allies, Hitler launched Operation Margarethe I on 15 March 1944, and ordered German troops to occupy Hungary.[79] In the meantime, some of those that had escaped prosecution for the 1942 massacres had joined various German military and police organisations. Feketehalmy-Czeydner had become the highest-ranking foreign officer in the Allgemeine SS, being promoted to SS-Obergruppenführer (lieutenant general). Grassy became a SS-Gruppenführer und Generalleutnant der Waffen-SS (major general) and was appointed to command the 25th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Hunyadi (1st Hungarian), and Zöldi joined the Gestapo. The case against them was re-opened after the German occupation, and in this second trial they were all found not guilty.[80]

After Germany occupied Hungary in March 1944, the genocidal policies of the authorities were applied comprehensively. Hungarian Jews were subjected to starvation and death marches, and those that had remained in the occupied territories were transported to extermination camps. From 26 April 1944, the remaining Jews in Bačka and Baranja, mostly women, but including children and the elderly, were rounded up into local concentration camps then moved to larger camps in Hungary proper. Between 14,000 and 15,000 Jews from Bačka, Baranja and other parts of Hungary were collected at Baja and Bácsalmás then transported to Auschwitz where most were killed. In September 1944, the workforce of the Bor mine was force-marched for several weeks back to extermination camps where the survivors were killed. One of the two groups of workers numbered 2,500, but only a few survived.[81]

Such was the extent of the Holocaust in the occupied territories that by the end of the war, nearly 85 per cent of the Jews that had been living in the Hungarian-occupied Yugoslav territories in April 1941 had been killed. This figure comprised about 13,500 Jews from Bačka and Baranja, and about 1,300 from Međimurje and Prekmurje.[82]

Flight of the Volksdeutsche and Yugoslav military control

In September 1944, the Hungarian authorities began evacuating the Székelys settled in the occupied territories since 1941 to Transdanubia.[83] Several days after the Soviet Red Army entered the Banat on 1 October 1944, the Germans began the evacuation of Bačka, including the local Volksdeutsche.[84] With the advance of the Partisans and the Red Army, some of the Volksdeutsche left the region while some others stayed, despite the situation.[85]

In October 1944, the Banat and Bačka were captured by Soviet troops. Subotica was captured on the 12 October.[86] After a few weeks, they withdrew and ceded full control of the region to the Partisans,[87] who established a military administration in the Banat, Bačka and Baranja on 17 October 1944.[88] In the first few weeks after Bačka returned to Yugoslav control, about 16,800 Hungarians were killed by Serbs in revenge for killings during the Hungarian occupation.[68] In November 1944, Tito declared that the Volksdeutsche of Yugoslavia were hostile to the nation, and ordered the internment of those living in areas under Partisan control.[89] About 60,000–70,000 Volksdeutsche had been evacuated from Bačka; while an additional 30,000–60,000 from Bačka were serving in the Wehrmacht at the time.[90]

Return to Yugoslav civilian control

On 15 February 1945, the Banat, Bačka and Baranja were transferred from military to civilian administration with a people's liberation committee (Serbo-Croatian: narodnooslobodilački odbor, NOO) taking control.[88] Until early 1945, the Yugoslav communist administration was characterized by persecution of some elements of the local population, with mass executions, internments and abuses.[87] Approximately 110,000 Volksdeutsche were interned, with around 46,000 dying in captivity due to poor conditions in the camps and the hard labour they were subjected to.[88] Victims of the communist regime were of various ethnic backgrounds and included some members of the Hungarian and Volksdeutsche population, as well as Serbs. The Hungarian writer Tibor Cseres has described in detail the crimes he claims the Yugoslav communists committed against Hungarians.[91] An estimated 5,000 Hungarians were killed following the return of the occupied territories to Yugoslav control.[92] About 40,000 Hungarians left the Banat, Bačka and Baranja after the war.[93] In late 1946, there were 84,800 refugees from Yugoslavia living in Hungary.[5]

Prosecutions

After these territories returned to Yugoslav control, the military and national courts in Bačka prosecuted collaborators who had killed about 10,000–20,000 civilians. The Security Service of Vojvodina captured the majority of these people. Meanwhile, some of those who were responsible for the 1942 massacres in southern Bačka were captured in, and extradited from, the newly formed People's Republic of Hungary.[94] In his book Mađari u Vojvodini: 1941–1946 ("Hungarians in Vojvodina: 1941–1946"; Novi Sad, 1996), Professor Sándor Kaszás from the University of Novi Sad listed a total of 1,686 executed war criminals by name, of whom around 1,000 were Hungarian.[92]

In a third trial in early 1946, the National Court of Hungary in Budapest found Szombathelyi, Feketehalmy-Czeydner, Grassy, Deák, and Zöldi guilty of involvement in the massacres in the occupied territories, and in carrying out the deportation of Jews to extermination camps. In accordance with the provisions of Article 14 of the Armistice Agreement, the Hungarian authorities then extradited them to Yugoslavia, where they underwent a fourth trial in Novi Sad in October 1946. They were all sentenced to death and executed the following month.[95]

Demographic and political changes

Of the approximately 500,000 Volksdeutsche living in Yugoslavia before the war, about half were evacuated, 50,000 died in Yugoslav concentration camps, 15,000 were killed by the Partisans and about 150,000 were deported to the Soviet Union as forced labourers. They were also stripped of their property. By 1948, only 55,337 Volksdeutsche remained in Yugoslavia.[89] Yugoslav Bačka is now part of Vojvodina, an autonomous province of Serbia, Yugoslav Baranja and Međimurje are part of modern-day Croatia, and Yugoslav Prekmurje is part of modern-day Slovenia.[96]

Formal apologies

In 2013, the National Assembly of Serbia adopted a declaration condemning the atrocities which were committed against Hungarian civilians between 1944 and 1945. On 26 June 2013, Hungarian President János Áder visited Serbia and formally apologised for war crimes committed against Serbian civilians by Hungarian forces during World War II.[97]

See also

- Administrative divisions of the Kingdom of Hungary (1941–44)

- Communist purges in Serbia in 1944–45

- Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–50)

- Hungary in World War II

Footnotes

^ ab Lemkin 2008, p. 631.

^ ab Lemkin 2008, pp. 261–262.

^ ab Pearson 1996, p. 95.

^ Ungváry 2011, pp. 75 and 71.

^ ab Karakaš Obradov 2012, p. 104.

^ Bán 2004, pp. 37–38.

^ Biondich 2008, p. 49.

^ Eberhardt 2003, p. 359.

^ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 170–172.

^ abcd Ungváry 2011, p. 70.

^ abcd Tomasevich 2001, p. 170.

^ ab Pogany 1997, p. 27.

^ Frank 2001, p. 171.

^ Eby 2007, p. 15.

^ Coppa 2006, p. 115.

^ ab Klajn 2007, p. 106.

^ Granville 2004, pp. 101–102.

^ ab Ramet 2006, p. 137.

^ Klajn 2007, p. 112.

^ Wehler 1980, p. 50.

^ Abbott, Thomas & Chappell 1982, p. 12.

^ Portmann 2007a, p. 76.

^ abcde Thomas & Szabo 2008, p. 14.

^ United States Army 1986, pp. 60–61.

^ abc Tomasevich 2001, p. 169.

^ Cseres 1991, pp. 61–65.

^ Komjáthy 1993, p. 134.

^ ab Neulen 2000, pp. 122–123.

^ Szabó 2005, p. 196, citing the obituaries of the "Royal Parachutist Squadron" (13 April) and in the periodical Pápa és Vidéke (27 April).

^ United States Army 1986, p. 65.

^ United States Army 1986, p. 64.

^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 84.

^ Kroener 2000, p. 93.

^ Ungváry 2011, p. 74.

^ ab Ungváry 2011, p. 73.

^ abcde Mojzes 2011, p. 87.

^ Tomasevich 2001, pp. 62 and 169–170.

^ ab Tomasevich 2001, pp. 172–173.

^ ab Lemkin 2008, p. 79.

^ Lemkin 2008, pp. 262–263.

^ Tomasevich 1969, p. 76.

^ Kovačić 2010, p. 62.

^ Ramet 2006, p. 115.

^ Kovačić 2010, pp. 62–63.

^ Karakaš Obradov 2012, p. 87.

^ Velikonja 2003, p. 164.

^ ab Ungváry 2011, p. 71.

^ ab Lemkin 2008, p. 263.

^ Cox 2005, p. 40.

^ Lemkin 2008, p. 262.

^ ab Pavlowitch 2008, p. 84.

^ Janjetović 2008, p. 156.

^ ab Ungváry 2011, p. 75.

^ Kostanick 1963, p. 28.

^ ab Tomasevich 2001, pp. 170–171.

^ Ramet 2006, p. 138.

^ ab Tomasevich 2001, p. 171.

^ Ramet 2006, pp. 136–137.

^ Macartney 1957, p. 39.

^ abc Tomasevich 2001, p. 172.

^ ab Jordan 2009, p. 129.

^ Macartney 1957, p. 13.

^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 583.

^ Mojzes 2011, pp. 89–90.

^ Prpa–Jovanović 2000, p. 58.

^ Banac 1988, p. 107.

^ Sajti 1987, p. 153.

^ ab Kocsis & Hodosi 1998, p. 153.

^ Kádár & Vági 2004, p. 32.

^ Granville 2004, p. 102.

^ Kádár & Vági 2004, p. 71.

^ Segel 2008, p. 25.

^ Klajn 2007, p. 118.

^ Klajn 2007, pp. 125–126.

^ Klajn 2007, p. 124.

^ Klajn 2007, p. 126.

^ Klajn 2007, pp. 117–118.

^ Macartney 1957, p. 315.

^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 173.

^ Kádár & Vági 2004, p. 155.

^ Mojzes 2011, pp. 90–91.

^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 591.

^ Macartney 1957, p. 347.

^ Wolff 2000, p. 152.

^ Ronen & Pelinka 1997, p. 59.

^ Macartney 1957, p. 378.

^ ab Ther & Sundhaussen 2001, p. 69.

^ abc Portmann 2007b, p. 15.

^ ab Ramet 2006, p. 159.

^ Ramet 2006, pp. 137–138.

^ Segel 2008, p. 26.

^ ab Portmann 2007b, p. 19.

^ Eberhardt 2003, p. 311.

^ Klajn 2007, pp. 133–136.

^ Braham 2000, pp. 259–260.

^ Stallaerts 2009, pp. 33–34.

^ B92 26 June 2013.

References

Books

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Abbott, Peter; Thomas, Nigel; Chappell, Mike (1982). Germany's Eastern Front Allies 1941–45, Vol 1. Oxford, Oxfordshire: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-475-8..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Bán, András D. (2004). Hungarian–British Diplomacy, 1938–1941: The Attempt to Maintain Relations. London, England: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-5660-7.

Banac, Ivo (1988). With Stalin against Tito: Cominformist splits in Yugoslav Communism. New York, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-2186-0.

Biondich, Mark (2008). "The Historical Legacy: The Evolution of Interwar Yugoslav Politics". In Cohen, Lenard J.; Dragović-Soso, Jasna. State Collapse in South-Eastern Europe: New Perspectives on Yugoslavia's Disintegration. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. pp. 43–74. ISBN 978-1-55753-460-6.

Braham, Randolph L. (2000). The Politics of Genocide: The Holocaust in Hungary. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2691-6.

Coppa, Frank J. (2006). Encyclopedia of Modern Dictators: From Napoleon to the Present. New York, New York: Peter Lang Press. ISBN 978-0-8204-5010-0.

Cox, John K. (2005). Slovenia: Evolving Loyalties. New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-27431-9.

Cseres, Tibor (1991). Vérbosszú a Bácskában [Vendetta in Bácska] (in Hungarian). Budapest, Hungary: Magvető Publications. OCLC 654722739.

Eberhardt, Piotr (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, and Analysis. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1833-7.

Eby, Cecil D. (2007). Hungary at War: Civilians and Soldiers in World War II. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-03244-3.

Frank, Tibor (2001). "Treaty Revision and Doublespeak: Hungarian Neutrality, 1939–1941". In Wylie, Neville. European Neutrals and Non-Belligerents During the Second World War. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire: Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–191. ISBN 978-0-521-64358-0.

Granville, Johanna C. (2004). The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-298-0.

Janjetović, Zoran (2008). "Die Vertreibungen auf dem Territorium des ehemaligen Jogoslawien" [The Expulsions from the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia]. In Bingen, Dieter; Borodziej, Włodzimierz; Troebst, Stefan. Vertreibungen europäisch erinnern? [Do You Remember the European Expulsions?] (in German). Wiesbaden, Germany: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 153–157. ISBN 978-0-231-70050-4.

Jordan, Peter (2009). Geographical Names as part of the Cultural Heritage. Vienna, Austria: Institut für Geographie und Regionalforschung der Universität Wien. ISBN 978-3-900830-67-0.

Kádár, Gábor; Vági, Zoltán (2004). Self-Financing Genocide: The Gold Train, the Becher Case and the Wealth of Hungarian Jews. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9241-53-4.

Klajn, Lajčo (2007). The Past in Present Times: The Yugoslav Saga. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-3647-6.

Kocsis, Károly; Hodosi, Eszter (1998). Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin. Budapest, Hungary: Simon Publications LLC. ISBN 978-1-931313-75-9.

Komjáthy, Anthony Tihamér (1993). Give Peace One More Chance!: Revision of the 1946 Peace Treaty of Paris. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-8905-9.

Kostanick, Huey Louis (1963). "The Geopolitics of the Balkans". In Jelavich, Charles; Jelavich, Barbara. The Balkans in Transition: Essays on the Development of Balkan Life and Politics Since the Eighteenth Century. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-208-01431-3.

Kroener, Bernhard (2000). Germany and the Second World War: Organization and Mobilization of the German Sphere of Power, Wartime Administration, Economy, and Manpower Resources 1942–1944/5. V/I. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822887-5.

Lemkin, Raphael (2008). Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Clark, New Jersey: The Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8.

Macartney, Carlile Aylmer (1957). October Fifteenth: A History of Modern Hungary, 1929–1945. 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press. OCLC 298105335.

Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the 20th Century. Plymouth, Devon: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-0663-2.

Neulen, Hans Werner (2000). In the Skies of Europe: Air Forces Allied to the Luftwaffe 1939–1945. Ramsbury, Wiltshire: The Crowood Press. ISBN 1-86126-799-1.

Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-895-5.

Pearson, Raymond (1996). "Hungary: A State Truncated, A Nation Dismembered". In Dunn, Seamus; Fraser, Thomas G. Europe and Ethnicity: World War 1 and Contemporary Ethnic Conflict. London, England: Psychology Press. pp. 88–109. ISBN 978-0-415-11996-2.

Pogany, Istvan S. (1997). Righting Wrongs in Eastern Europe. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press ND. ISBN 978-0-7190-3042-0.

Portmann, Michael (2007a). Serbien und Montenegro im zweiten Weltkrieg 1941–1945 [Serbia and Montegro in the Second World War 1941–1945] (in German). Norderstedt, Germany: GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-638-70869-2.

Portmann, Michael (2007b). Communist Retaliation and Persecution on Yugoslav Territory During and After WWII (1943–1950). Norderstedt, Germany: GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-638-66048-8.

Prpa–Jovanović, Branka (2000). "The Making of Yugoslavia: 1830–1945". In Udovički, Jasminka; Ridgeway, James. Burn This House: The Making and Unmaking of Yugoslavia. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 43–63. ISBN 978-0-8223-2590-1.

Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

Ronen, Dov; Pelinka, Anton (1997). The Challenge of Ethnic Conflict, Democracy and Self-determination in Central Europe. Portland, Oregon: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-4752-4.

Sajti, Enikő A. (1987). Délvidék, 1941–1944: A magyar kormanyok delszlav politikaja [The Southern Territories, 1941–1944: The Policies of the Hungarian Government towards Yugoslavs] (in Hungarian). Budapest, Hungary: Kossuth Könyvkiadó. ISBN 978-963-09-3078-9.

Segel, Harold B. (2008). The Columbia Literary History of Eastern Europe since 1945. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13306-7.

Stallaerts, Robert (2009). Historical Dictionary of Croatia (3 ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6750-5.

Ther, Philipp; Sundhaussen, Holm (2001). Nationalitätenkonflikte im 20. Jahrhundert: Ursachen von inter-ethnischer Gewalt im Vergleich [Ethnic Conflicts in the 20th Century: Comparisons of the Causes of Inter-Ethnic Violence] (in German). Wiesbaden, Germany: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04494-3.

Thomas, Nigel; Szabo, Laszlo (2008). The Royal Hungarian Army in World War II. Oxford, Oxfordshire: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-324-7.

Tomasevich, Jozo (1969). "Yugoslavia During the Second World War". In Vucinich, Wayne S. Contemporary Yugoslavia: Twenty Years of Socialist Experiment. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 59–118. OCLC 47922.

Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

Ungváry, Krisztián (2011). "Vojvodina under Hungarian Rule". In Ramet, Sabrina P.; Listhaug, Ola. Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 70–89. ISBN 978-0-230-27830-1.

United States Army (1986) [1953]. The German Campaigns in the Balkans (Spring 1941): A Model of Crisis Planning. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 104-4.

Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

Wehler, Hans–Ulrich (1980). Nationalitätenpolitik in Jugoslawien [Nationality Policy in Yugoslavia] (in German). Göttingen, West Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-01322-9.

Wolff, Stefan (2000). German Minorities in Europe: Ethnic Identity and Cultural Belonging. New York, New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-57181-738-9.

Journals

Karakaš Obradov, Marica (2012). "The Migrations of Hungarian National Group during the Second World War and in the Post-War Period in Croatia". Tokovi istorije (in Croatian). Belgrade, Serbia: Institute for Recent History of Serbia (1): 87–105. ISSN 0354-6497.

Kovačić, Davor (2010). "The Međimurje Question in Police Intelligence Relationships of the Independent State of Croatia and the Kingdom of Hungary During the Second World War". Polemos: časopis za interdisciplinarna istraživanja rata i mira (in Croatian). Zagreb: Croatian Sociological Association and Jesenski & Turk Publishing House. XIII (26): 59–78. ISSN 1331-5595.

Szabó, Miklós (2005). "Establishment of the Hungarian Air Force and the Activity of the Hungarian Royal Honvéd Air Force in World War II Respectively" (PDF). Nação e Defesa. 3. Póvoa de Santo Adrião, Portugal: Europress. 110: 191–210. ISSN 0870-757X.

Websites

"Hungarian president apologizes for crimes". B92. 26 June 2013.