Carolingian Empire

Empire of the Romans and Franks Romanorum sive Francorum imperium (Latin) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 800–888 | |||||||||||

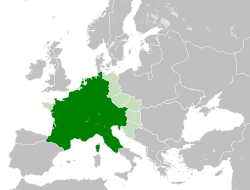

The Carolingian Empire at its greatest extent in 814

| |||||||||||

| Capital | Aachen | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Coronation of Charlemagne | 800 | ||||||||||

• Division | 843 | ||||||||||

• Death of Charles the Fat | 888 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 800 | 1,112,000 km2 (429,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 800 | 10,000,000–20,000,000 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large empire in western and central Europe during the early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lombards of Italy from 774. In 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III in an effort to revive the Roman Empire in the west during a vacancy in the throne of the eastern Roman Empire. After a civil war (840–43) following the death of Emperor Louis the Pious, the empire was divided into autonomous kingdoms, with one king still recognised as emperor, but with little authority outside his own kingdom. The unity of the empire and the hereditary right of the Carolingians continued to be acknowledged.

In 884, Charles the Fat reunited all the kingdoms of Francia for the last time, but he died in 888 and the empire immediately split up. With the only remaining legitimate male of the dynasty a child, the nobility elected regional kings from outside the dynasty or, in the case of the eastern kingdom, an illegitimate Carolingian. The illegitimate line continued to rule in the east until 911, while in the western kingdom the legitimate Carolingian dynasty was restored in 898 and ruled until 987 with an interruption from 922 to 936.

The size of the empire at its inception was around 1,112,000 square kilometres (429,000 sq mi), with a population of between 10 and 20 million people.[1] To the south it bordered the Emirate of Córdoba and, after 824, the Kingdom of Pamplona; to the north it bordered the kingdom of the Danes; to the west it had a short land border with Brittany, which was later reduced to a tributary; and to the east it had a long border with the Slavs and the Avars, who were defeated and their land incorporated into the empire. In southern Italy, the Carolingians' claims to authority were disputed by the Byzantines (eastern Romans) and the vestiges of the Lombard kingdom in the Principality of Benevento.

Use of the term "Carolingian Empire" is a modern convention. The language of official acts in the empire was Latin. The empire was referred to variously as universum regnum ("the whole kingdom", as opposed to the regional kingdoms), Romanorum sive Francorum imperium[a] ("empire of the Romans and Franks"), Romanum imperium ("Roman empire") or even imperium christianum ("Christian empire").[2]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Rise of the Carolingians (c. 732 – 768)

1.2 During the reign of Charlemagne (768–814)

1.3 Reign of Louis the Pious and the civil war (814–843)

1.4 After the Treaty of Verdun (843–877)

1.5 Decline (877–888)

1.6 Divisions in 887–88

2 Demographics

3 Government

3.1 Military

3.2 Capitals

3.3 Household

3.4 Officials

3.5 Legal system

3.6 Coinage

3.7 Subdivision

3.8 Placitum generalis

3.9 Oaths

3.10 Capitularies

4 List of emperors

5 See also

6 Notes

7 References

8 External links

History

Rise of the Carolingians (c. 732 – 768)

Though Charles Martel chose not to take the title king (as his son Pepin III would, or emperor, as his grandson Charlemagne) he was absolute ruler of virtually all of today's continental Western Europe north of the Pyrenees. Only the remaining Saxon realms, which he partly conquered, Lombardy, and the Marca Hispanica south of the Pyrenees were significant additions to the Frankish realms after his death.

Martel was also the founder of all the feudal systems and merit system that marked the Carolingian Empire, and Europe in general during the Middle Ages, though his son and grandson would gain credit for his innovations. Further, Martel cemented his place in history with his defense of Christian Europe against a Muslim army at the Battle of Tours in 732. The Iberian Saracens had incorporated Berber light horse cavalry with the heavy Arab cavalry to create a formidable army that had almost never been defeated. Christian European forces, meanwhile, lacked the powerful tool of the stirrup. In this victory, Charles earned the surname Martel ("the Hammer").[3]Edward Gibbon, the historian of Rome and its aftermath, called Charles Martel "the paramount prince of his age".

Pepin III accepted the nomination as king by Pope Zachary in about 751. Charlemagne's rule began in 768 at Pepin's death. He proceeded to take control of the kingdom following his brother Carloman's death, as the two brothers co-inherited their father's kingdom. Charlemagne was crowned Roman Emperor in the year 800.[4]

During the reign of Charlemagne (768–814)

The Dorestad Brooch, Carolingian-style cloisonné jewelry from c. 800. Found in the Netherlands, 1969.

The Carolingian Empire during the reign of Charlemagne covered most of Western Europe, as the Roman Empire once had. Unlike the Romans, who ventured beyond the Rhine only for vengeance after the disaster at Teutoburg Forest (9 AD), Charlemagne decisively crushed all Germanic resistance and extended his realm to the Elbe, influencing events almost to the Russian Steppes.

Charlemagne's reign was one of near-constant warfare, personally leading many of his campaigns. He seized the Lombard Kingdom in 774, led a failed campaign into Spain in 778, extended his domain into Bavaria in 788, ordered his son Pepin to campaign against the Avars in 795, and conquered Saxon territories in wars and rebellions fought from 772 to 804.[3][5]

Prior to the death of Charlemagne, the Empire was divided among various members of the Carolingian dynasty. These included King Charles the Younger, son of Charlemagne, who received Neustria; King Louis the Pious, who received Aquitaine; and King Pepin, who received Italy. Pepin died with an illegitimate son, Bernard, in 810, and Charles died without heirs in 811. Although Bernard succeeded Pepin as King of Italy, Louis was made co-Emperor in 813, and the entire Empire passed to him with Charlemagne's death in the winter of 814.[6]

Reign of Louis the Pious and the civil war (814–843)

Louis the Pious often had to struggle to maintain control of the Empire. King Bernard of Italy died in 818 in imprisonment after rebelling a year earlier, and Italy was brought back into Imperial control. Louis' show of penance for Bernard's death in 822 greatly reduced his prestige as Emperor to the nobility. Meanwhile, in 817 Louis had established three new Carolingian Kingships for his sons from his first marriage: Lothar was made King of Italy and co-Emperor, Pepin was made King of Aquitaine, and Louis the German was made King of Bavaria. His attempts in 823 to bring his fourth son (from his second marriage), Charles the Bald into the will was marked by the resistance of his eldest sons, and the last years of his reign were plagued by civil war.

Lothar was stripped of his co-Emperorship in 829[why?] and was banished to Italy, but the following year his sons attacked Louis' empire and dethroned him in favor of Lothar. The following year Louis attacked his sons' Kingdoms, stripped Lothar of his Imperial title and granted the Kingdom of Italy to Charles. Pepin and Louis the German revolted in 832, followed by Lothar in 833, and together they imprisoned Louis the Pious and Charles. In 835, peace was made within the family, and Louis was restored to the Imperial throne. When Pepin died in 838, Louis crowned Charles king of Aquitaine, whilst the nobility elected Pepin's son Pepin II, a conflict which was not resolved until 860 with Pepin's death. When Louis the Pious finally died in 840, Lothar claimed the entire empire irrespective of the partitions.

The division of 843

As a result, Charles and Louis the German went to war against Lothar. After losing the Battle of Fontenay, Lothar fled to his capital at Aachen and raised a new army, which was inferior to that of the younger brothers. In the Oaths of Strasbourg, in 842, Charles and Louis agreed to declare Lothar unfit for the imperial throne. This marked the East-West division of the Empire between Louis and Charles until the Verdun Treaty. Considered a milestone in European history, the Oaths of Strasbourg symbolize the birth of both France and Germany.[7] The partition of Carolingian Empire was finally settled in 843 by and between Louis the Pious' three sons in the Treaty of Verdun.[8]

After the Treaty of Verdun (843–877)

Lothar received the Imperial title, the Kingship of Italy, and the territory between the Rhine and Rhone Rivers, collectively called the Central Frankish Realm. Louis was guaranteed the Kingship of all lands to the east of the Rhine and to the north and east of Italy, which was called the Eastern Frankish Realm which was the precursor to modern Germany. Charles received all lands west of the Rhone, which was called the Western Frankish Realm.

Lothar retired Italy to his eldest son Louis II in 844, making him co-Emperor in 850. Lothar died in 855, dividing his kingdom into three parts: the territory already held by Louis remained his, the territory of the former Kingdom of Burgundy was granted to his third son Charles of Burgundy, and the remaining territory for which there was no traditional name was granted to his second son Lothar II, whose realm was named Lotharingia.

Louis II, dissatisfied with having received no additional territory upon his father's death, allied with his uncle Louis the German against his brother Lothar and his uncle Charles the Bald in 858. Lothar reconciled with his brother and uncle shortly after. Charles was so unpopular that he could not raise an army to fight the invasion and instead fled to Burgundy. He was only saved when the bishops refused to crown Louis the German King. In 860, Charles the Bald invaded Charles of Burgundy's Kingdom but was repulsed. Lothar II ceded lands to Louis II in 862 for support of a divorce from his wife, which caused repeated conflicts with the Pope and his uncles. Charles of Burgundy died in 863, and his Kingdom was inherited by Louis II.

Lothar II died in 869 with no legitimate heirs, and his Kingdom was divided between Charles the Bald and Louis the German in 870 by the Treaty of Meerssen. Meanwhile, Louis the German was involved in disputes with his three sons. Louis II died in 875, and named Carloman, the eldest son of Louis the German, his heir. Charles the Bald, supported by the Pope, was crowned both King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor. The following year, Louis the German died. Charles tried to annex his realm too, but was defeated decisively at Andernach, and the Kingdom of the eastern Franks was divided between Louis the Younger, Carloman of Bavaria and Charles the Fat.

Decline (877–888)

Copy of the Ludwigslied, an epic poem celebrating the victory of Louis III of West Francia over the Vikings

The Empire, after the death of Charles the Bald, was under attack in the north and west by the Vikings and was facing internal struggles from Italy to the Baltic, from Hungary in the east to Aquitaine in the west. Charles the Bald died in 877 crossing the Pass of Mont Cenis, and was succeeded by his son, Louis the Stammerer as King of the Western Franks, but the title of Holy Roman Emperor lapsed. Louis the Stammerer was physically weak and died two years later, his realm being divided between his eldest two sons: Louis III gaining Neustria and Francia, and Carloman gaining Aquitaine and Burgundy. The Kingdom of Italy was finally granted to King Carloman of Bavaria, but a stroke forced him to abdicate Italy to his brother Charles the Fat and Bavaria to Louis of Saxony. Also in 879, Boso, Count of Arles founded the Kingdom of Lower Burgundy in Provence.

In 881, Charles the Fat was crowned the Holy Roman Emperor while Louis III of Saxony and Louis III of Francia died the following year. Saxony and Bavaria were united with Charles the Fat's Kingdom, and Francia and Neustria were granted to Carloman of Aquitaine who also conquered Lower Burgundy. Carloman died in a hunting accident in 884 after a tumultuous and ineffective reign, and his lands were inherited by Charles the Fat, effectively recreating the Empire of Charlemagne.

Charles, suffering what is believed to be epilepsy, could not secure the kingdom against Viking raiders, and after buying their withdrawal from Paris in 886 was perceived by the court as being cowardly and incompetent. The following year his nephew Arnulf of Carinthia, the illegitimate son of King Carloman of Bavaria, raised the standard of rebellion. Instead of fighting the insurrection, Charles fled to Neidingen and died the following year in 888, leaving a divided entity and a succession mess.

Divisions in 887–88

The Empire of the Carolingians was divided: Arnulf maintained Carinthia, Bavaria, Lorraine and modern Germany; Count Odo of Paris was elected King of Western Francia (France), Ranulf II became King of Aquitaine, Italy went to Count Berengar of Friuli, Upper Burgundy to Rudolph I, and Lower Burgundy to Louis the Blind, the son of Boso of Arles, King of Lower Burgundy and maternal grandson of Emperor Louis II. The other part of Lotharingia became the duchy of Burgundy.[9]

Demographics

The largest cities in the Carolingian Empire around the year 800:

Rome 50,000. Paris 25,000. Regensburg 25,000. Metz 25,000. Mainz 20,000. Speyer 20,000. Tours 20,000. Trier 15,000. Cologne 15,000. Lyon 12,000. Worms 10,000. Poitiers 10,000. Provins 10,000. Rennes 10,000. Rouen 10,000.[10][11][12]

Government

The government, administration, and organization of the Carolingian Empire were forged in the court of Charlemagne in the decades around the year 800. In this year, Charlemagne was crowned emperor and adapted his existing royal administration to live up to the expectations of his new title. The political reforms wrought in Aachen were to have an immense impact on the political definition of Western Europe for the rest of the Middle Ages. The Carolingian improvements on the old Merovingian mechanisms of governance have been lauded by historians for the increased central control, efficient bureaucracy, accountability, and cultural renaissance.

The Carolingian Empire was the largest western territory since the fall of Rome, but historians have come to suspect the depth of the emperor's influence and control. Legally, the Carolingian emperor exercised the bannum, the right to rule and command, over all of his territories. Also, he had supreme jurisdiction in judicial matters, made legislation, led the army, and protected both the Church and the poor. His administration was an attempt to organize the kingdom, church, and nobility around him, however, its efficacy was directly dependent upon the efficiency, loyalty and support of his subjects.

Military

It has long been held that the dominance of the Carolingian military was based on a "cavalry revolution" led by Charles Martel in 730. However, the stirrup, which made the 'shock cavalry' lance charge possible, was not introduced to the Frankish kingdom until the late eighth century.[13] Instead, the Carolingian military success rested primarily on novel siege technologies and excellent logistics.[14] However, large numbers of horses were used by the Frankish military during the age of Charlemagne. This was because horses provided a quick, long-distance method of transporting troops, which was critical to building and maintaining such a large empire.[13]

Capitals

Interior of the Palatine Chapel in Aachen

No permanent capital city existed in the empire, the itinerant court being a typical characteristic of all Western European kingdoms at this time. Some "main residences" can, however, be distinguished. In the first year of his reign, Charlemagne went to Aachen (French: Aix-la-Chapelle; Italian: Aquisgrana) for the first time. He began to build a palace twenty years later (788). The palace chapel, constructed in 796, later became Aachen Cathedral. Charlemagne spent most winters between 800 and his death (814) at Aachen, which he made the joint capital with Rome, in order to enjoy the hot springs. Charlemagne organized his empire into 350 counties, each led by an appointed count. Counts served as judges, administrators, and enforcers of capitularies. To enforce loyalty, he set up the system of missi dominici, meaning "envoys of the lord". In this system, one representative of the Church and one representative of the Emperor would head to the different counties every year and report back to Charlemagne on their status.

Household

The royal household was an itinerant body (until c. 802) which moved around the kingdom making sure good government was upheld in the localities. The most important positions were the chaplain (who was responsible for all ecclesiastical affairs in the kingdom), and the count of the palace (Count palatine) who had supreme control over the household. It also included more minor officials e.g. chamberlain, seneschal, and marshal. The household sometimes led the army (e.g. Seneschal Andorf against the Bretons in 786).

Possibly associated with the chaplain and the royal chapel was the office of the chancellor, head of the chancery, a non-permanent writing office. The charters produced were rudimentary and mostly to do with land deeds. There are 262 surviving from Charles’ reign as opposed to 40 from Pepin’s and 350 from Louis the Pious.

Officials

There are 3 main offices which enforced Carolingian authority in the localities:

The Comes (Latin: count). Appointed by Charles to administer a county. The Carolingian Empire (except Bavaria) was divided up into between 110 and 600 counties, each divided into centenae which were under the control of a vicar. At first, they were royal agents sent out by Charles but after c. 802 they were important local magnates. They were responsible for justice, enforcing capitularies, levying soldiers, receiving tolls and dues and maintaining roads and bridges. They could technically be dismissed by the king but many offices became hereditary. They were also sometimes corrupt although many were exemplary e.g. Count Eric of Friuli. Provincial governors eventually evolved who supervised several counts.

The Missi Dominici (Latin: dominical emissaries). Originally appointed ad hoc, a reform in 802 led to the office of missus dominicus becoming a permanent one. The Missi Dominici were sent out in pairs. One was an ecclesiastic and one secular. Their status as high officials was thought to safeguard them from the temptation of taking bribes. They made four journeys a year in their local missaticum, each lasting a month, and were responsible for making the royal will and capitularies known, judging cases and occasionally raising armies.

The Vassi Dominici. These were the king’s vassals and were usually the sons of powerful men, holding ‘benefices’ and forming a contingent in the royal army. They also went on ad hoc missions.

Legal system

Around 780 Charlemagne reformed the local system of administering justice and created the scabini, professional experts on the law. Every count had the help of seven of these scabini, who were supposed to know every national law so that all men could be judged according to it.

Judges were also banned from taking bribes and were supposed to use sworn inquests to establish facts.

In 802, all law was written down and amended (the Salic law was also amended in both 798 and 802, although even Einhard admits in section 29 that this was imperfect). Judges were supposed to have a copy of both the Salic law code and the Ripuarian law code.

Coinage

A denarius minted by Prince Adelchis of Benevento in the name of Emperor Louis II and Empress Engelberga, showing the expansion of Carolingian authority in southern Italy which Louis achieved

Coinage had a strong association with the Roman Empire, and Charlemagne took up its regulation with his other imperial duties. The Carolingians exercised controls over the silver coinage of the realm, controlling its composition and value. The name of the emperor, not of the minter, appeared on the coins. Charlemagne worked to suppress mints in northern Germany on the Baltic sea.

Subdivision

The Frankish kingdom was subdivided by Charlemagne into three separate areas to make administration easier. These were the inner "core" of the kingdom (Austrasia, Neustria, and Burgundy) which were supervised directly by the missatica system and the itinerant household. Outside this was the regna where Frankish administration rested upon the counts, and outside this was the marcher areas where ruled powerful governors. These marcher lordships were present in Brittany, Spain, and Bavaria.

Charles also created two sub-kingdoms in Aquitaine and Italy, ruled by his sons Louis and Pepin respectively. Bavaria was also under the command of an autonomous governor, Gerold, until his death in 796. While Charles still had overall authority in these areas they were fairly autonomous with their own chancery and minting facilities.

Placitum generalis

The annual meeting, the Placitum Generalis or Marchfield, was held every year (between March and May) at a place appointed by the king. It was called for three reasons: to gather the Frankish host to go on a campaign, to discuss political and ecclesiastical matters affecting the kingdom and to legislate for them, and to make judgments. All important men had to go the meeting and so it was an important way for Charles to make his will known. Originally the meeting worked effectively however later it merely became a forum for discussion and for nobles to express their dissatisfaction.

Oaths

The oath of fidelity was a way for Charles to ensure loyalty from all his subjects. As early as 779 he banned sworn guilds between other men so that everyone took an oath of loyalty only to him. In 789 (in response to the 786 rebellion) he began legislating that everyone should swear fidelity to him as king, however in 802 he expanded the oath greatly and made it so that all men over age 12 swore it to him.

Capitularies

The five greatest capitularies of Charlemagne’s reign are:

- The Capitulary of Herstal of 779. This is a short capitulary and launched according to Ganshof in response to a crisis in Aquitaine, Italy, and Spain. It is concerned a lot with ordo, making sure that the church is working correctly, also with reinforcing the wergild and Frankish ideals. Notably forced the usage of tithes.

Admonitio Generalis of 789. “Blueprint for a new society” mentioning social issues for the first time. The first 58 clauses (of 82) reiterate decisions made by previous church councils and much is also to do with ordo.- The Capitulary of Frankfurt of 794. This is mainly to do with theology and speaks out against adoptionism and iconoclasm.

- The Programmatic Capitulary of 802. This shows an increasing sense of vision in society.

- The Capitulary for the Jews of 814, delineating the prohibitions of Jews engaging in commerce or money-lending.

List of emperors

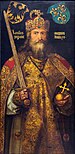

This table shows only those Carolingians who were crowned as emperor by the pope in Rome. For other Carolingian kings, see King of the Franks. For the later emperors, see Holy Roman Emperor.

| Later image | Name | Imperial coronation | Death | Contemporary coin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charles I (Charlemagne) | 25 December 800 | 28 January 814 |  |

| Louis I (Louis the Pious) | 1st: 11 September 813[15] 2nd: 5 October 816 | 20 June 840 |  |

| Lothair I | 5 April 823 | 29 September 855 |  |

| Louis II | 1st: Easter 850 2nd: 18 May 872 | 12 August 875 | |

| Charles II (Charles the Bald) | 29 December 875 | 6 October 877 |  |

| Charles III (Charles the Fat) | 12 February 881 | 13 January 888 |  |

See also

Carolingian Renaissance

- Carolingian architecture

- Carolingian art

- List of Carolingian monasteries

Notes

^ Sometimes with Romanum (Roman) replacing Romanorum (of the Romans) and atque (and) replacing sive (or).

References

^ Post-Roman towns, trade and settlement in Europe and Byzantium – Joachim Henning – Google Břger. Books.google.dk. Retrieved 24 December 2014.The size of the Carolingian empire can be roughly estimated at 1,112,000 km²

.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Ildar H. Garipzanov, The Symbolic Language of Authority in the Carolingian World (c.751–877) (Leiden: Brill, 2008).

^ ab Magill, Frank (1998). Dictionary of World Biography: The Middle Ages, Volume 2. Routledge. pp. 228, 243. ISBN 9781579580414.

^ Rosamond McKitterick, Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity, Cambridge University Press, 2008

ISBN 978-0-521-88672-7

^ Davis, Jennifer (2015). Charlemagne's Practice of Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 9781316368596.

^ Joanna Story, Charlemagne: Empire and Society, Manchester University Press, 2005

ISBN 978-0-7190-7089-1

^ "Die Geburt Zweier Staaten – Die Straßburger Eide vom 14. February 842 | Wir Europäer | DW.DE | 21.07.2009". Dw-world.de. 2009-07-21. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

^ Eric Joseph Goldberg, Struggle for Empire: Kingship and Conflict Under Louis the German, 817–876, Cornell University Press, 2006

ISBN 978-0-8014-3890-5

^ Simon MacLean, Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2003

ISBN 978-0-521-81945-9

^ Bachrach, B. (2013). Charlemagne's Early Campaigns (768–777): A Diplomatic and Military Analysis. Brill. p. 67. ISBN 9789004244771. Retrieved 2014-10-06.

^ Dudley, L. (2008). Information Revolutions in the History of the West. Edward Elgar. p. 26. ISBN 9781848442801. Retrieved 2014-10-06.

^ Claus, Edda (June 1997). "The Rebirth of a Communications Network: Europe at the Time of the Carolingians (thesis)". papyrus.bib.umontreal.ca. Retrieved 2014-10-06.

^ ab Hooper, Nicholas / Bennett, Matthew. The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: the Middle Ages Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 12–13

ISBN 0-521-44049-1,

ISBN 978-0-521-44049-3

^ Bowlus, Charles R. The Battle of Lechfeld and its Aftermath, August 955: The End of the Age of Migrations in the Latin West Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006, pg. 49

ISBN 0-7546-5470-2,

ISBN 978-0-7546-5470-4

^ Egon Boshof: Ludwig der Fromme. Darmstadt 1996, p. 89

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carolingian period. |

The Making of Charlemagne's Europe (768–814) (freely available database of prosopographical and socio-economic data from Carolingian legal documents, produced and maintained by King's College London)