Nerva–Antonine dynasty

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

Nerva–Antonine dynasty | ||||||||||||||

Chronology | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Family | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Succession | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

The Nerva–Antonine dynasty was a dynasty of seven Roman Emperors who ruled over the Roman Empire from 96 CE to 192 CE. These Emperors are Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Lucius Verus, Marcus Aurelius, and Commodus.

The first five of the six successions within this dynasty were notable in that the reigning Emperor adopted the candidate of his choice to be his successor. Under Roman law, an adoption established a bond legally as strong as that of kinship. Because of this, all but the first and last of the Nerva-Antonine emperors are called Adoptive Emperors.

The importance of official adoption in Roman society has often been considered[1] as a conscious repudiation of the principle of dynastic inheritance and has been deemed as one of the factors of the period's prosperity.[2] However, this was not a new practice. It was common for patrician families to adopt, and Roman emperors had adopted heirs in the past: the Emperor Augustus had adopted Tiberius and the Emperor Claudius had adopted Nero. Julius Caesar, dictator perpetuo and considered to be instrumental in the transition from Republic to Empire, adopted Gaius Octavius, who would become Augustus, Rome's first emperor. Moreover, there was a family connection as Trajan adopted his first cousin once removed and great-nephew by marriage Hadrian, and Hadrian made his half-nephew by marriage and heir Antoninus Pius adopt both Hadrian's second cousin three times removed and half-great-nephew by marriage Marcus Aurelius, also Antoninus' nephew by marriage, and the son of his original planned successor, Lucius Verus. The naming by Marcus Aurelius of his son Commodus was considered to be an unfortunate choice and the beginning of the Empire's decline.[3]

With Commodus' murder in 192, the Nerva-Antonine dynasty came to an end; it was followed by a period of turbulence known as the Year of the Five Emperors.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Nerva–Trajan dynasty

1.2 Antonine dynasty

2 Five Good Emperors

2.1 Alternative hypothesis

2.2 The Jewish viewpoint

3 Nerva–Antonine family tree

4 References

History

Nerva–Trajan dynasty

Nerva was the first of the dynasty. Though his reign was short, it saw a partial reconciliation between the army, Senate and commoners. Nerva adopted as his son the popular military leader Trajan. In turn, Hadrian succeeded Trajan; he had been the latter's heir presumptive and averred that he had been adopted by him on Trajan's deathbed.

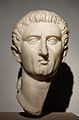

Nerva

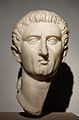

Trajan

Hadrian

Antonine dynasty

The Antonines are four Roman Emperors who ruled between 138 and 192: Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus and Commodus.

In 138, after a long reign dedicated to the cultural unification and consolidation of the empire, the Emperor Hadrian named Antoninus Pius his son and heir, under the condition that he adopt both Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. Hadrian died that same year, and Antoninus began a peaceful, benevolent reign. He adhered strictly to Roman traditions and institutions and shared his power with the Roman Senate.

Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus succeeded Antoninus Pius in 161 upon that emperor's death, and co-ruled until Verus' death in 169. Marcus continued the Antonine legacy after Verus' death as an unpretentious and gifted administrator and leader. He died in 180 and was followed by his biological son, Commodus.

Antoninus Pius

Marcus Aurelius

Lucius Verus

Commodus

Five Good Emperors

The rulers commonly known as the "Five Good Emperors" were Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius.[4] The term was coined based on what the political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli wrote in 1503:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

From the study of this history we may also learn how a good government is to be established; for while all the emperors who succeeded to the throne by birth, except Titus, were bad, all were good who succeeded by adoption, as in the case of the five from Nerva to Marcus. But as soon as the empire fell once more to the heirs by birth, its ruin recommenced.[5]

Machiavelli argued that these adopted emperors, through good rule, earned the respect of those around them:

Titus, Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus, and Marcus had no need of praetorian cohorts, or of countless legions to guard them, but were defended by their own good lives, the good-will of their subjects, and the attachment of the senate.[5]

The 18th-century historian Edward Gibbon, in his work The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, opined that their rule was a time when "the Roman Empire was governed by absolute power, under the guidance of wisdom and virtue".[6] Gibbon believed these benevolent dictators and their moderate policies were unusual and contrasted with their more tyrannical and oppressive successors.

Gibbon went so far as to state:

If a man were called to fix the period in the history of the world during which the condition of the human race was most happy and prosperous, he would, without hesitation, name that which elapsed from the death of Domitian to the accession of Commodus. The vast extent of the Roman Empire was governed by absolute power, under the guidance of virtue and wisdom. The armies were restrained by the firm but gentle hand of four successive emperors, whose characters and authority commanded respect. The forms of the civil administration were carefully preserved by Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian and the Antonines, who delighted in the image of liberty, and were pleased with considering themselves as the accountable ministers of the laws. Such princes deserved the honour of restoring the republic, had the Romans of their days been capable of enjoying a rational freedom.

At the time when the above was written, the idea of enlightened absolutism was widely accepted in various European countries.

Alternative hypothesis

One hypothesis posits that adoptive succession is thought to have arisen because of a lack of biological heirs. All but the last of the adoptive emperors had no legitimate biological sons to succeed them. They were thus obliged to pick a successor somewhere else; as soon as the Emperor could look towards a biological son to succeed him, adoptive succession was set aside.

The dynasty may be broken up into the Nerva–Trajan dynasty (also called the Ulpian dynasty after Trajan's nomen gentile 'Ulpius') and Antonine dynasty (after their common name Antoninus).

The Jewish viewpoint

The concept of "The Five Good Emperors" reflects the internal Roman point of view. As regards their treatment of Roman citizens, these five Emperors clearly seem better than other Emperors – specifically, better than Domitian who immediately preceded them and Commodus who immediately followed them – and this view was taken up by later Europeans, drawing on Roman historical sources. It is, however, not necessarily the point of view of provincials and of Rome's neighbors – particularly, of those targeted by one or more of these emperors in a war of conquest or in the suppression of a revolt.

In many cases, such diverging points of view did not leave a record; for example, there is no surviving historical source recording the Dacians' opinion of Trajan who conquered them. However, in the case of the Jews, who suffered greatly at the suppression of the Bar Kokhba revolt by Hadrian, there is an extensive Rabbinical literature offering a very different perspective to that of Roman historiography. While the Roman view lumped Hadrian and Antoninus Pius together among the Five Good Emperors, Jews tended to contrast the Bad Hadrian with the Good Antoninus. When Jewish sources mention Hadrian it is always with the epitaph "may his bones be crushed" (שחיק עצמות or שחיק טמיא, the Aramaic equivalent[7]), an expression never used even with respect to Vespasian or Titus, who destroyed the Second Temple; conversely, Antoninus Pius is positively remembered in the Jewish tradition, as having ameliorated the Jews' lot and abolished many of the harsh decrees which Hadrian had imposed on them.

Nerva–Antonine family tree

Nerva–Antonine family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes: Except where otherwise noted, the notes below indicate that an individual's parentage is as shown in the above family tree.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Note: Marcus Aurelius co-reigned with Lucius Verus from 161 until Verus' death in 169.

References

^ E.g. by Machiavelli and Gibbon

^ "Adoptive Succession". Retrieved 2007-09-18.

^ "Decline of the Roman Empire". Retrieved 2007-09-18.

^ McKay, John P.; Hill, Bennett D.; Buckler, John; Ebrey, Patricia B.; & Beck, Roger B. (2007). A History of World Societies (7th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, v-vi.

ISBN 978-0-618-61093-8.

^ ab Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy, Book I, Chapter 10.

^ Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, I.78.

^ The Aramaic version, "שחיק טמיא", is used, e.g., in Genesis Rabbah 78:1. This is referenced by Rashi in his comment on the phrase, "טמא לנפש", in his commentary on Numbers 5:2. The other two locations in Genesis Rabbah referenced in Rashi's comment, 10:3 and 28:3, use the Hebrew version, "שחיק עצמות"