Kingdom of Württemberg

Kingdom of Württemberg Königreich Württemberg | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1805–1918 | |||||||||

Flag  Coat of arms | |||||||||

Motto: Furchtlos und treu "Fearless and loyal" | |||||||||

Anthem: Württemberger Hymne "Württemberg Anthem" | |||||||||

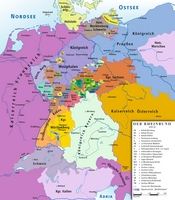

The Kingdom of Württemberg within the German Empire before 1918 | |||||||||

| Status | Electorate of the Holy Roman Empire (1805–1806) Member of the Confederation of the Rhine (1806–1813) Member of the German Confederation (1815–1866) Federal State of the German Empire (1871–1918) | ||||||||

| Capital | Stuttgart | ||||||||

| Common languages | Swabian German | ||||||||

| Religion | Protestant Roman Catholic | ||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1805–1816 | Frederick I | ||||||||

• 1816–1864 | William I | ||||||||

• 1864–1891 | Charles I | ||||||||

• 1891–1918 | William II | ||||||||

| Minister-President | |||||||||

• 1821–1831 | Christian von Otto | ||||||||

• 1918 | Theodor Liesching | ||||||||

| Legislature | Landtag | ||||||||

• Upper Chamber | Herrenhaus | ||||||||

• Lower Chamber | Abgeordnetenhaus | ||||||||

| Historical era | Napoleonic Wars / World War I | ||||||||

• Elevated to kingdom | 26 December 1805 | ||||||||

• German Revolution | 29 November 1918 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1910 | 19,508 km2 (7,532 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1910 | 2,437,574 | ||||||||

| Currency | Württemberg gulden (1806–1873) German Goldmark (1873–1914) German Papiermark (1914–1918) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Kingdom of Württemberg (German: Königreich Württemberg; German pronunciation: [ˌkøːnɪkʁaɪç ˈvʏʁtəmbɛʁk]) was a German state that existed from 1805 to 1918, located within the area that is now Baden-Württemberg. The kingdom was a continuation of the Duchy of Württemberg, which existed from 1495 to 1805.[1]

Prior to 1495, Württemberg was a County in the former Duchy of Swabia, which had dissolved after the death of Duke Conradin in 1268.

The borders of the Kingdom of Württemberg, as defined in 1813, lay between 47°34' and 49°35' north and 8°15' and 10°30' east. The greatest distance north to south comprised 225 kilometres (140 mi) and the greatest east to west was 160 kilometres (99 mi). The border had a total length of 1,800 kilometres (1,100 mi) and the total area of the state was 19,508 square kilometres (7,532 sq mi).

The kingdom had borders with Bavaria on the east and south, with Baden in the north, west and south. The southern part surrounded the Prussian province of Hohenzollern on most of its sides and touched on Lake Constance.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Frederick II

1.2 William I

1.3 Charles I

1.4 William II

2 Government

2.1 Constitution

2.2 Religion

2.3 Education

2.4 Army

2.5 Finances

2.6 Population

3 Economy

3.1 Agriculture

3.1.1 Swine

3.1.2 Fruit Trees

3.2 Mining

3.3 Manufacturing

3.4 Commerce

3.5 Transport

4 Notes

5 Further reading

6 External links

History

Frederick II

(Born: 1754 Elevated: 1797 Died: 1816)

The Kingdom of Württemberg as it existed from the end of the Napoleonic Wars to the end of World War I. From 1815 to 1866 it was a member state of the German Confederation and from 1871 to 1918 it was a federal state in the German Empire.

Frederick II, the Duke of Württemberg, assumed the title of King Frederick I on 1 January 1806. He abrogated the constitution, and united Old and New Württemberg. Subsequently, he placed the property of the church under government control,[2] and greatly extended the borders of the kingdom by the process of mediatisation.

In 1806, Frederick joined the Confederation of the Rhine and received further territory with 160,000 inhabitants. Later, by the Peace of Vienna of October 1809, about 110,000 more people came under his rule. In return for these favours, Frederick joined French Emperor Napoleon in his campaigns against Prussia, Austria and Russia. Of the 16,000 of his subjects who marched to Moscow, only a few hundred returned. After the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, Frederick deserted the French emperor and, by a treaty with Metternich at Fulda in November 1813, he secured the confirmation of his royal title and of his recent acquisitions of territory. Meanwhile his troops marched into France with the allies. In 1815, the King joined the German Confederation but the Congress of Vienna made no change to the extent of his lands. In the same year, he laid before the representatives of his people the outline of a new constitution but they rejected it and, in the midst of the commotion that ensued, Frederick died on 30 October 1816.[2]

William I

(Born: 1781 Succeeded: 1816 Died: 1864)

Crown of Württemberg

Frederick was succeeded by his son, William I who, after much discussion, granted a new constitution in September 1819. This constitution (with subsequent modifications) remained in force until 1918 (see Württemberg). The desire for greater political freedom did not entirely fade under the constitution of 1819 and, after 1830, some transitory unrest occurred.[2]

A period of quiet set in and the condition of the kingdom, its education, its agriculture, its trade and economy improved. Both in public and in private matters, William's frugality helped to repair the country's shattered finances. The inclusion of Württemberg in the German Zollverein and the construction of railways fostered trade.[2]

The revolutionary movement of 1848 did not leave Württemberg untouched, although no violence took place in the territory. William had to dismiss Johannes Schlayer (1792–1860) and his other ministers, and appoint men with more liberal ideas, proponents of a united Germany. William proclaimed a democratic constitution but, as soon as the movement had spent its force, he dismissed the liberal ministers and, in October 1849, Schlayer and his associates returned to power. In 1851, by interfering with popular electoral rights, the King and his ministers succeeded in assembling a servile diet that surrendered the privileges gained since 1848. In this way the authorities restored the constitution of 1819 and power passed into bureaucratic hands. A concordat with the papacy proved almost the last act of William's long reign, but the diet repudiated the agreement.[2]

Charles I

(Born: 1823 Succeeded: 1864 Died: 1891)

Map of the Kingdom of Württemberg and Province of Hohenzollern in 1888

In July 1864, Charles I succeeded his father William as king and almost at once had to face considerable difficulties. In the competition between Austria and Prussia for supremacy in Germany, William had consistently taken the Austrian side and the new king continued this policy. In 1866, Württemberg took up arms on behalf of Austria in the Austro-Prussian War but, three weeks after the Battle of Königgrätz (3 July 1866), the allies suffered a comprehensive defeat at the Battle of Tauberbischofsheim. The Prussians occupied northern Württemberg and negotiated a peace in August 1866. Württemberg paid an indemnity of 8,000,000 gulden, and concluded a secret offensive and defensive treaty with her conqueror.[2] Württemberg was a party to the St Petersburg Declaration of 1868.

The end of the struggle against Prussia allowed a renewal of democratic agitation in Württemberg, but this had achieved no tangible results when the war broke out in 1870. Although Württemberg had continued to be antagonistic to Prussia, the kingdom shared in the national enthusiasm which swept over Germany. Württemberger troops played a creditable part in the Battle of Wörth and in other operations of the war.[2]

In 1871, Württemberg became a member of the new German Empire but retained control of her own post office, telegraphs and railways. She also had certain special privileges with regard to taxation and the army. For the next ten years, Württemberg enthusiastically supported the new order. Many important reforms ensued, especially in the area of finance, but a proposal to unify the railway system with that of the rest of Germany failed. After reductions in taxation in 1889, changes to the constitution were considered. Charles wished to strengthen the conservative element in the chambers but the laws of 1874, 1876 and 1879 effected only slight change.[2]

William II

(Born: 1859 Succeeded: 1891 Deposed: 1918 Died: 1921)

When King Charles died suddenly on 6 October 1891, he was succeeded by his nephew, William II, who continued Charles' policies.

Constitutional discussions continued and the election of 1895 returned a powerful party of democrats. William had no sons, nor had his only Protestant kinsman, Duke Nicholas (1833–1903). Consequently, power was due to pass to a Roman Catholic branch of the family, raising difficulties concerning the relations between church and state. As of 1910 the heir to the throne was Duke Albert (b. 1865) of the Altshausen family.[2]

An older Catholic line, that of the Duke of Urach, was bypassed due to a morganatic marriage contracted in 1800. A protestant morganatic line included Mary of Teck, who married George V of the United Kingdom.

Between 1900 and 1910 the political history of Württemberg centred round constitutional and educational questions. The constitution was revised in 1906 and the education system was improved in 1909. In 1904 the Württemberg railway system integrated with that of the rest of Germany.[2]

King William abdicated on 30 November 1918, following Germany's defeat in the First World War. The kingdom was replaced with the Free People's State of Württemberg. After World War II, Württemberg was divided between the American and French occupation zones and became part of two new states; Württemberg-Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern. These two states merged with South Baden in 1952 to become the modern German state of Baden-Württemberg within the Federal Republic of Germany.

Government

Constitution

The Kingdom of Württemberg functioned as a constitutional monarchy within the German Empire, with four votes in the Federal Council (German: Bundesrat) and seventeen in the Imperial Diet (German: Reichstag). The constitution rested on a law of 1819, amended in 1868, 1874 and 1906. The king received a civil list (annual grant) of 103,227 pounds sterling.[2]

The kingdom possessed a bicameral legislature. The upper chamber (German: Standesherren) comprised:[2]

- adult princes of the blood[2]

- heads of noble families from the rank of count (German: Graf) upwards[2]

- representatives of territories (German: Standesherrschafien) that possessed votes in the old German Imperial Diet or in the local diet[2]

- not more than 6 members nominated by the king[2]

- 8 members of knightly rank[2]

- 6 ecclesiastical dignitaries[2]

- 1 representative of the University of Tübingen[2]

- 1 representative of the Stuttgart University of Technology[2]

- 2 representatives of commerce and industry[2]

- 2 representatives of agriculture[2]

- 1 representative of handicrafts[2]

The lower house (German: Abgeordnetenhaus) had 92 members:[2]

- 63 representatives from the administrative divisions (German: Oberamtsbezirke)[2]

- 6 representatives from Stuttgart, elected by proportional representation[2]

- 6 representatives, one from each of the six chief provincial towns[2]

- 17 members from the two electoral divisions (German: Landeswahlkreise), elected by proportional representation[2]

The king appointed the president of the upper chamber; after 1874 the lower chamber elected its own chairman. Members of each house had to be over twenty-five years of age.[2]

Württemberg parliamentary terms lasted six years and all male citizens over twenty-five had the right to vote in the ballots.[2]

The highest executive power rested in the hands of the Ministry of State (German: Staatsministerium), consisting of six ministers: justice, foreign affairs (with the royal household, railways, posts and telegraphs), interior, public worship and education, war and finance.[2]

The kingdom also had a Privy Council, consisting of the ministers and some nominated councillors (German: wirkliche Staatsräte), who advised the sovereign. The judges of a special supreme court of justice called the German: Staatsgerichtshof functioned as the guardians of the constitution. This court was partly elected by the chambers and partly appointed by the king. Each of the chambers had the right to impeach ministers.[2]

The nation comprised four departments or districts (German: Kreise), subdivided into sixty-four divisions (German: Oberamtsbezirke), each under a headman (German: Oberamtmann) assisted by a local council (German: Amtsversammlung). Each department was headed by its own government (Latin: Regierung).[2]

Religion

Authority over the churches resided with the king. So long as he belonged to the Evangelical State Church in Württemberg, the king was its guardian. The Protestant Church was controlled (under the Minister of Religion and Education) by a consistory and a synod. The consistory comprised a president, 9 councillors and a general superintendent or prelate from each of six principal towns. The synod consisted of a representative council including both lay and clerical members.[2]

The Roman Catholic Church in the kingdom was led by the Bishop of Rottenburg-Stuttgart, who answered to the Archbishop of Freiburg im Breisgau. Politically, it obeyed a Roman Catholic council which was appointed by the government.[2]

A state-appointed council (Oberkirchenbehörde) regulated Judaism after 1828,[2] forming the Israelite Religious Community of Württemberg (German: Israelitische Religionsgemeinschaft Württembergs).

Education

The kingdom claimed universal literacy (reading and writing) among citizens over the age of ten years. Higher Education institutions included the University of Tübingen, the Stuttgart University of Technology, the veterinary college and the commercial college at Stuttgart, and the agricultural college of Hohenheim. Gymnasia and other schools existed in the larger towns, while every commune had a primary school. Numerous schools and colleges existed for women. Württemberg also had a school of viticulture.[2]

Army

Under the terms of a military convention of 25 November 1870, the troops of Württemberg formed the XIII (Royal Württemberg) Corps of the Imperial German Army.[2]

Finances

Until 1873, the kingdom and some neighbouring states used the Württemberg gulden. From 1857, the vereinsthaler was introduced alongside it and from 1873 onwards, both were replaced by the gold mark.

The state revenue for 1909–1910 totalled an estimated £4,840,520, nearly balanced by expenditure. About one-third of the revenue derived from railways, forests and mines, about £1,400,000 from direct taxation, and the remainder from indirect taxes, the post-office and sundry items.[2]

In 1909 the public debt amounted to £29,285,335, of which more than £27,000,000 resulted from railway construction.[2]

Of the expenditure, over £900,000 went towards public worship and education, and over £1,200,000 went in interest and debt repayment. The kingdom contributed £660,000 to the treasury of the German Empire.[2]

Population

Population statistics for Württemberg's four departments (Kreise) for 1900 and 1905 appear below.[2]

| District (Kreis) | Area (sq mi.) | Area (km2) | Population 1900 | Population 1905 | Density (pop./sq mi.) 1905 | Density (pop./km2) 1905 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Neckarkreis (Neckar) | 1,286 | 3,330 | 745,669 | 811,478 | 631 | 244 |

Schwarzwaldkreis (Schwarzwald/Black Forest) | 1,844 | 4,780 | 509,258 | 541,662 | 293 | 113 |

Jagstkreis (Jagst) | 1,985 | 5,140 | 400,126 | 407,059 | 205 | 79 |

Donaukreis (Danube) | 2,419 | 6,270 | 514,427 | 541,980 | 224 | 87 |

| Total | 7,534 | 19,520 | 2,169,480 | 2,302,179 | 306 | 118 |

Settlement density was concentrated in the Neckar valley from Esslingen northward.[2]

The mean annual population increase from 1900 to 1905 amounted to 1.22%. 8.5% of births occurred out of wedlock.

Classified according to religion circa 1905, about 69% of the population professed Protestantism, 30% Roman Catholicism, and about 0.5% Judaism. Protestants predominated in the Neckar district and Roman Catholics in the Danube district.

The people of the north-west represent Alamannic stock, those of the north-east Franconian, and those of the centre and south Swabian.[2]

Economy

In 1910, there were 506,061 persons working in agriculture, 432,114 in industrial occupations and 100,109 in trade and commerce.[2]

The largest towns included Stuttgart (with Cannstatt), Ulm, Heilbronn, Esslingen am Neckar, Reutlingen, Ludwigsburg, Göppingen, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Tübingen, Tuttlingen and Ravensburg.[2]

Agriculture

The territory of Württemberg was largely agricultural; of its 19,508 square kilometres (7,532 sq mi), 44.9% comprised agricultural land and gardens, 1.1% vineyards, 17.9% meadows and pastures and 30.8% forest. It possessed rich meadowlands, cornfields, orchards, gardens and hills covered with vines. The chief agricultural products were oats, spelt, rye, wheat, barley and hops, peas and beans, maize, fruit, (chiefly cherries and apples), beets and tobacco, as well as garden and dairy produce. Livestock included cattle, sheep, pigs and horses.[2]

Württemberg has a long history of producing red wines, growing different varieties from those grown in other German wine regions. The Württemberg wine region centred on the valley of the Neckar and several of its tributaries, the Rems, Enz, Kocher and Jagst.

Swine

The Mohrenköpfle is the traditional swine. On the orders of King Wilhelm I, masked pigs (Maskenschweine?) were imported from Central China in 1820/21, in order to improve pig breeding in the kingdom of Baden-Württemberg. This crossbreeding with the "Chinese pigs" was particularly successful within the stocks of domestic pigs in the Hohenlohe region and the area around the town of Schwäbisch Hall.[3][4]

Fruit Trees

To help people to help themselves Württemberg plant a alley of trees.(Dienstbarkeit on private ground).

The tree farms of Wilhelm and the Brüdergemeinde delivered for free.[5]

Mining

In former times iron ore was mined on the Heuberg.[6] Fidel Eppler was the name of the mine inspector. The buttress wood was bought in Truchtelfingen and used by Lautlingen miners at the Hörnle area.[7]

In Oberdigisheim Geppert in 1738 SHW-Ludwigsthal produced iron ore.[8]

From an old 3.5 km mine in a ooidal iron ore seam (Doggererzflöz) in Weilheim is wood in the Tuttlinger Fruchtkasten.[9]

Steel was produced in Tuttlingen by the Schwäbische Hüttenwerke in Ludwigstal, which produces now iron brakes.

had a factory. Ooidal iron ore (Bohnerz aus Eisenroggenstein) was found.[10] After the Franco-Prussian War the mining was stopped.[11]

The main minerals of industrial importance found in the kingdom were salt and iron. The salt industry came to prominence at the beginning of the 19th century. The iron industry had greater antiquity but the lack of coal slowed its development. Other minerals included granite, limestone, ironstone and fireclay.[2]

Manufacturing

Textile manufacturers produced linen, woollen and cotton fabrics, particularly at Esslingen and Göppingen, and paper-making was prominent in Ravensburg, Heilbronn and throughout Lower Swabia.[2]

Assisted by the government, manufacturing industries developed rapidly during the later years of the 19th century, notably metal-working, especially branches that required skilled workmanship. Particular importance attached to iron and steel goods, locomotives (for which Esslingen enjoyed a good reputation), machinery, cars, bicycles, small-arms (in the Mauser factory at Oberndorf am Neckar), scientific and artistic appliances, pianos (at Stuttgart), organs and other musical instruments, photographic apparatus, clocks (in the Black Forest), electrical apparatus, and gold and silver goods.[2]

Chemical works, potteries, cabinet-making workshops, sugar factories, breweries and distilleries operated throughout the kingdom. Hydropower and petrol largely compensated for the lack of coal, and liquid carbonic acid was produced from natural gas springs beside the Eyach, a tributary of the Neckar.[2]

Commerce

The kingdom's principal exports included cattle, cereals, wood, pianos, salt, oil, leather, cotton and linen fabrics, beer, wine and spirits. Commerce centred on the cities of Stuttgart, Ulm, Heilbronn and Friedrichshafen. Stuttgart, once called the Leipzig of South Germany[by whom?], boasted an extensive book trade.[2] The kingdom had creative inventors; Gottlieb Daimler, the first car manufacturer, incorporated his business in 1900 as Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft, and its successor company Mercedes-Benz always had plants near Stuttgart. At Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin constructed airships from 1897 until his death in 1917.

Transport

In 1907 the kingdom had 2,000 km (1,200 mi) of railways, of which all except 256 km (159 mi) belonged to the state. Navigable waterways included the Neckar, the Schussen, Lake Constance and the Danube downstream from Ulm. The kingdom had fairly good quality roads, the oldest of them of Roman construction. Württemberg, like Bavaria, retained the control of its own postal and telegraph service following the foundation of the new German Empire in 1871.[2]

Notes

^ Vann, James Allen (1984). The Making of a State: Württemberg, 1593–1793. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1553-5..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzaaabacadaeafagahaiajakalamanaoapaqarasatauavawaxayazba One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Württemberg". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Württemberg". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

^ Mohrenköpfle Wilhelma

^ Mohrenköpfle

^ Apfelgeschichte auf Apfelgut Sulz

^ Birgit Tuchen, Landesdenkmalamt, ed., Pingen (in German), Stuttgart: Landesdenkmalamt 2004, p. 123

^ Hermann Bitzer, Hermann Bitzer Studienrat Rosenfeld †1964, ed., Tailfinger Heimatbuch 1954 (in German), p. 35

^ Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg Abt.Wirtschaftsarchiv Stuttgart Hohenheim (ed.), Archiv SHW: B 40 Bü 1232 (in German), Harras, Ludwigsthal

^ Fruchtkasten: Abteilung Ludwigsthal. In: Pressemiteilungen. 21 November 2016.

^ Friedrich von Alberti, Die Gebirge des Königreichs Würtemberg, in besonderer Beziehung auf Halurgie (in German), Stuttgart und Tübingen: J. G. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung 1826, p. 124

^ : Eisenindustrie In: Schwarzwälder Bote, 28 September 2016.

Further reading

Marquardt, Ernst (1985). Geschichte Württembergs (3rd ed.). Stuttgart: DVA. ISBN 3421062714.

(in German)

Weller, Karl; Weller, Arnold (1989). Württembergische Geschichte im südwestdeutschen Raum (10th ed.). Stuttgart: Theiss. ISBN 3806205876.

(in German)

Wilson, Peter H. (1995). War, state, and society in Württemberg, 1677–1793. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521473020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kingdom of Württemberg. |

Jews in Württemberg (Settlement in the Middle Ages – impoverishment and expulsion decree of 1521 – new settlements and equality – WWII and Holocaust) (Encyclopaedia Judaica)