Human nose

| Human nose | |

|---|---|

Front view of human nose | |

Cross-section of the interior of a nose | |

| Details | |

| Artery | sphenopalatine artery, greater palatine artery |

| Vein | facial vein |

| Nerve | external nasal nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nasus |

| MeSH | D009666 |

| TA | A06.1.01.001 A01.1.00.009 |

| FMA | 46472 |

Anatomical terminology [edit on Wikidata] | |

The human nose is the most protruding part of the face that bears the nostrils, and is the first organ of the respiratory system. The nose is also the principal organ in the olfactory system. The shape of the nose is determined by the nasal bones and the nasal cartilages, including the nasal septum which separates the nostrils and divides the nasal cavity into two. On average the nose of a male is larger than that of a female.

The main function of the nose is respiration, and the nasal mucosa lining the nasal cavity and the paranasal sinuses carries out the necessary conditioning of inhaled air by warming and moistening it. Nasal conchae, shell-like bones in the walls of the cavities play a major part in this process. Filtering of the air by nasal hair in the nostrils prevents large particles from entering the lungs. Sneezing is a reflex to expel unwanted particles from the nose that irritate the mucosal lining. Sneezing can transmit infections, because aerosols are created in which the droplets can harbour pathogens.

Another major function of the nose is olfaction, the informing of odours that the sense of smell carries out. The area of olfactory epithelium, in the upper nasal cavity contains specialised olfactory cells responsible for this function.

The nose is also involved in the function of speech. Nasal vowels and nasal consonants are produced in the process of nasalisation. The nasal cavity is the third most effective vocal resonator.

There are many plastic surgery procedures on the nose, known as rhinoplasties available to correct various structural defects or to change the shape of the nose. Defects may be congenital, result from nasal disorders or from trauma and these are carried out by reconstructive surgery. Procedures used to change a nose shape electively are carried out by cosmetic surgeries.

Contents

1 Structure

1.1 Bones

1.2 Cartilages

1.3 External nose

1.4 Internal nose

1.5 Nose shape

1.6 Muscles

2 Blood supply and drainage

2.1 Lymphatic drainage

3 Nerve supply

4 Development

5 Function

5.1 Respiration

5.2 Olfaction

5.3 Speech

6 Clinical significance

7 Society and culture

8 Evolutionary hypotheses

8.1 Neanderthals

8.2 Humans

9 Neoteny

10 See also

11 References

12 External links

Structure

Several bones and nasal cartilages make up the bony-cartilaginous framework of the nose, and the internal structure. The nose is also made up of types of soft tissue such as skin, epithelia, mucous membrane, muscles, nerves, and blood, and in the skin there are sebaceous glands.

The framework of the nose is made up of bone and cartilage which provides strong protection for the internal structures of the nose.

The arrangement of the cartilages allows flexibility through muscle control to enable airflow to be modified.

Bones

Bones of the nose and septal cartilage

Roof of the mouth showing position of palatine bones making up the floor of the nose, and forming the posterior nasal spine for the attachment of the musculus uvulae.

The nasal part of the frontal bone ends in a serrated nasal notch that articulates at the front with the paired nasal bones, and at the sides with the small lacrimal bones and with the frontal process of each maxilla. The nasal bones in the upper part of the nose are joined together by the midline internasal suture. They join with the septal cartilage at a junction known as the rhinion. The rhinion is the midpoint of the internasal suture at the join with the cartilage, and from the rhinion to the apex, or tip, the framework is of cartilage.

Above and to the back, the bony upper part of the nasal septum is made up of the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, and the bony lower part is made up of the vomer bone that lies below. The floor of the nose is made up of the incisive bone and the horizontal plates of the palatine bones, and this makes up the hard palate of the roof of the mouth. The two horizontal plates join together at the midline and form the posterior nasal spine that gives attachment to the musculus uvulae in the uvula.

The internal roof of the nasal cavity is composed of the horizontal, perforated cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone through which pass sensory fibers of the olfactory nerve (CN1). Below and behind the cribriform plate, sloping down at an angle, is the face of the sphenoid bone.

The two maxilla bones join at the base of the nose at the lower nasal midline between the nostrils, and at the top of the philtrum to form the anterior nasal spine. This thin projection of bone holds the cartilaginous center of the nose.[1][2]

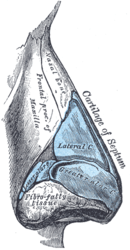

Cartilages

Nasal cartilages

The nasal cartilages are the septal, lateral, major alar, and minor alar cartilages.

The septal nasal cartilage, extends from the nasal bones in the midline, to the bony part of the septum in the midline, posteriorly. It then passes along the floor of the nasal cavity. The septum is quadrangular; the upper half is atttached to the two lateral nasal cartilages which are fused to the dorsal septum in the midline, and laterally attached, with loose ligaments, to the bony margin of the anterior nasal aperture, while the inferior ends of the lateral cartilages are free (unattached); the minor alar cartilages are adjacent to the lateral cartilages in the fibroareolar connective tissue.

Beneath the lateral cartilages lay the major alar cartilages, which swing outwards, from medial attachments, to the caudal septum in the midline (the medial crura) to an intermediate crus (shank) area. Finally, the major alar cartilages flare outwards, above and to the side (superolaterally), as the lateral crura; these cartilages are mobile, unlike the upper lateral cartilages. Furthermore, some persons present anatomical evidence of nasal scrolling—i.e. an outward curving of the lower borders of the upper lateral-cartilages, and an inward curving of the cephalic borders of the alar cartilages.

External nose

The nasal root is the top of the nose that attaches the nose to the forehead.[3] The nasal root is above the bridge and below the glabella, forming an indentation known as the nasion at the frontonasal suture where the frontal bone meets the nasal bones.

The nasal ridge (nasal dorsum) is the border between the root and the tip of the nose which in profile can be variously shaped.[4]

The ala of the nose (wing of the nose) is the lower lateral surface of the external nose, cartilaginous in makeup, and which flares out to form a rounded eminence around the nostril.[4]

The skin of the nose varies in thickness along its length. From the glabella to the bridge the skin is thick, fairly flexible, and mobile. It tapers to the bridge where it is thinnest and least flexible as it adheres to the bony framework. The rest of the skin of the lower nose is as thick as the top section and has more sebaceous glands. The glands produce sebum in a higher concentration than on other parts of the body.

Sexual dimorphism is evident in the larger nose of the male. This is due to the increased testosterone that thickens the brow ridge and the bridge of the nose making it wider.[5]

Internal nose

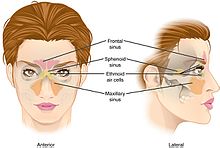

Nasal cavities

Paranasal sinuses

The nasal cavity is the large internal space of the nose. The cavity is divided into two cavities (fossae) by the nasal septum, which separates the nostrils. The nasal vestibule is the frontmost part of the nasal cavity, and is enclosed by cartilages. On the lateral wall of each cavity are three shell-like bones called conchae, arranged as superior, middle, and inferior conchae. Below each concha is a corresponding superior, middle, and inferior nasal meatus. The conchae are also known as turbinates. Sometimes when the superior concha is narrow, a fourth supreme nasal concha is present situated above and sharing the space with the superior concha.[6] The conchae extend along the length of the nasal cavity.[7]

The internal structures and cavities, including the conchae and paranasal sinuses form an integrated system for the conditioning (moistening and warming) and filtering of the air breathed in through the nose.[8] This functioning also includes the major role of the nasal mucosa, and the resulting conditioning of the air before it reaches the lungs is important in maintaining the internal environment and proper functioning of the lungs. The turbulence created by the conchae and meatuses optimises the warming, moistening, and filtering of the mucosa.[9] A major protective role is thereby provided by these structures of the upper respiratory tract, in the passage of air to the more delicate structures of the lower respiratory tract.[8]

At the back of the nasal cavity there are two openings, one from each fossa, called choanae that give entrance to the nasopharynx and rest of the respiratory tract. The choanae are also called the posterior nostrils.

There is a nasal valve area in the nose that is responsibe for providing resistance to the flow of air. This enables increased warming and moistening of the air. Two valves are often referred to for this area, an internal nasal valve and an external nasal valve. The internal nasal valve is the narrowest part of the airway.[10][11] The internal nasal valve is in the middle third of the nose and the external nasal valve is in the alar wall.[12] The angle between the septum and the sidewall needs to be sufficient for unobstructed airflow.[13]

The vestibule of the nose is lined with skin.[3] A mucous ridge known as the limen nasi separates the vestibule from the rest of the nasal cavity and marks the change from the skin of the vestibule to the respiratory epithelium of the rest of the nasal cavity. This area is also known as a mucocutaneous junction that has a dense microvasculature.[14] The respiratory epithelium is a ciliated tissue with mucus-secreting goblet cells, that maintains the nasal moisture and protects the respiratory tract from infection and atmospheric particulates. The respiratory epithelium also covers the paranasal sinuses.[15] This lining of the sinuses is closely adhered to the membrane of the underlying bone and is referred to as mucoperiosteum.[16]

There are narrow openings called sinus ostia from the paranasal sinuses that allow drainage into the nasal cavity. Adults have a high concentration of cilia in the ostia. The increased cilia and the narrowness of the sinus openings allow for an increased time for moisturising, and warming. The cilia in the sinuses beat towards the openings into the nasal cavity. Most of the ostia open into the middle meatus and the anterior ethmoid, that together are termed the osteomeatal complex.[15] The maxillary sinus is the largest of the sinuses and drains into the middle meatus.

Nose shape

The shape of the nose varies widely due to differences in the nasal bone shapes and formation of the bridge of the nose. Some nose shapes were classified for surgeries by Eden Warwick in Nasology 1848:

Class I. The aquiline nose.

Class II. The grecian nose.

Class III. The African nose.

Class IV. The hawk nose.

Class V. The snub nose.

Class VI. The celestial nose.

Nose shapes used in Topinard's nasal index.

Other terms are used to describe the shape of the nose, and can also include a reference to the nasal index used to classify ethnicity: Leptorrhine describes a long, narrow nose.[17]Hyperleptorrhine is a very long, narrow nose with a nasal index of 40 to 55. Platyrrhine is a short, broad nose. Paul Topinard developed the nasal index for studies in India. The nasal index is the ratio of the width of the nose to the nasal height. Some of the types used in Nasology are also used by Topinard. He took narrow shapes as in 1-5 to be European; medium width shape 6 were "yellow races"; broad nose shape 7 were African, and broad nose shape 8 were taken to be Melanesian and Australian Aboriginal.

Some deformities of the nose are named, such as the pug nose and the saddle nose. The pug nose is characterised by by excess tissue from the apex that is out of proportion to the rest of the nose. A low and underdeveloped nasal bridge may also be evident.[18] A saddle nose is mostly associated with trauma to the nose but can be caused by other conditions such as cocaine abuse and leprosy.[19]

Some birth defects such as Down syndrome commonly present a small nose with a flattened nasal bridge. This can be due to the absence of one or both nasal bones, shortened nasal bones, or nasal bones that have not fused in the midline.[20][21]

Muscles

The movements of the nose are controlled by groups of facial and neck muscles that are set deep to the skin. There are four interconnected groups connected by the superficial fascia that covers, invests and forms the terminations of the muscles.

The elevator muscle group includes the procerus muscle that helps to flare the nostrils; and the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle, which lifts the upper lip and the alae.

The depressor muscle group includes the alar nasalis muscle and the depressor septi nasi muscle.

The compressor muscle group includes the transverse nasalis muscle.

The dilator muscle group includes the dilator naris muscle that expands the nostrils; it is in two parts: (i) the dilator naris anterior muscle, and (ii) the dilator naris posterior muscle.

Blood supply and drainage

The nose, in particular the nasal cavity, is well supplied with blood from branches of both the internal carotid artery, and the external carotid artery.

- Internal carotid

The main branches from the interior carotid are the anterior ethmoidal artery, and the posterior ethmoidal artery that supplies the septum, and these derive from the ophthalmic artery. One of the terminal branches of the ophthalmic artery is the dorsal nasal artery which divides into two branches. One branch crosses the root of the nose and joins with the angular artery, and the other branch joins with the lateral nasal branch of facial artery which supplies the nasal ridge and alae.

- External carotid

Branches from the external carotid artery are the sphenopalatine artery, the greater palatine artery, the superior labial artery, and the angular artery.

The lateral walls of the nasal cavity and the septum are suppled by the sphenopalatine artery, and by the anterior and posterior ethmoid arteries. There is additional supply from the superior labial artery and the greater palatine artery.

The nasal ridge is supplied by branches of the internal maxillary artery (infraorbital) and the ophthalmic arteries from the common carotid artery system.

The arteries supplying the nasal cavity converge in the front lower part of the septum in a plexus known as Kiesselbach's plexus.

- Drainage

Veins of the nose include the angular vein that drains the side of the nose, receiving lateral nasal veins from the alae. The angular vein joins with the superior labial vein. Some small veins from the nasal ridge (dorsum) drain to the nasal arch of the frontal vein at the root of the nose.

In the posterior region of the cavity, specifically in the posterior part of the inferior meatus is a venous plexus known as Woodruff's plexus. This plexus is made up of large thin-walled veins with little soft tissue such as muscle or fiber. The mucosa of the plexus is thin with very few structures.[22]

Lymphatic drainage

The nasal part of the lymphatic system arises from the superficial mucosa, and drains posteriorly to the retropharyngeal lymph nodes, and anteriorly to either the upper deep cervical lymph nodes (in the neck), or to the submandibular glands (in the lower jaw), or into both the nodes and the glands of the neck and the jaw.

Nerve supply

The trigeminal nerve gives sensation to the nose, the face, and the upper jaw (maxilla).

Nerve supply to the nose is from the first two branches of the trigeminal nerve (CN V), the ophthalmic nerve (CN V1) and the maxillary nerve(CN V2).

The facial nerve supplies the facial muscles including those that move the nose.

- Ophthalmic innervation

- Nasociliary nerve – conveys sensation to the skin area of the nose, and the mucous membrane of the anterior (front) nasal cavity.

- Anterior ethmoid nerve – conveys sensation in the anterior (front) half of the nasal cavity: (a) the internal areas of the ethmoid sinus and the frontal sinus; and (b) the external areas, from the nasal tip to the rhinion: the anterior tip of the terminal end of the nasal-bone suture.

- Posterior ethmoid nerve – serves the superior (upper) half of the nasal cavity, the sphenoids, and the ethmoids.

- Intratrochlear nerve – conveys sensation to the medial region of the eyelids, the palpebral conjunctiva, the nasion (nasolabial junction), and the bony dorsum.

- Maxillary innervation

- Maxillary nerve – conveys sensation to the upper jaw, the face and the nostrils.

Internal nasal branches of infraorbital nerve – conveys sensation to the septum.- Zygomatic nerve – through the zygomatic bone and the zygomatic arch, conveys sensation to the cheekbone areas.

- Sphenopalatine nerve – divides into the lateral branch and the septal branch, and conveys sensation from the rear and the central regions of the nasal cavity.

The supply of parasympathetic nerves to the face and the upper jaw (maxilla) derives from the greater superficial petrosal (GSP) branch of cranial nerve VII, the facial nerve. The GSP nerve joins the deep petrosal nerve (of the sympathetic nervous system), derived from the carotid plexus, to form the vidian nerve (in the vidian canal) that traverses the pterygopalatine ganglion (an autonomic ganglion of the maxillary nerve), wherein only the parasympathetic nerves form synapses, which serve the lacrimal gland and the glands of the nose and of the palate, via the (upper jaw) maxillary division of cranial nerve V, the trigeminal nerve.

Development

The developing head at about four weeks.

At four weeks, gestational age, the neural crest cells (the precursors of the nose) begin their caudal migration (from the posterior) towards the midface. Two symmetrical nasal placodes (the future olfactory epithelium) develop inferiorly. In the sixth week they invaginate to form two nasal pits. The nasal pits then divide into the medial and the lateral nasal processes (the future upper lip and nose). The medial processes then form the septum, the philtrum, and the premaxilla of the nose; the lateral processes form the sides of the nose; and the mouth forms from the stomodeum (the anterior ectodermal portion of the alimentary tract), which is inferior to the nasal complex.

A nasobuccal membrane separates the mouth from the nose; respectively, the inferior oral cavity (the mouth) and the superior nasal cavity (the nose). As the nasal pits deepen, said development forms the choanae, the two openings that connect the nasal cavity and the nasopharynx (upper part of the pharynx that is continuous with the nasal passages). Initially, primitive-form choanae develop, which then further develop into the secondary, permanent choanae.

At ten weeks, the cells differentiate into muscle, cartilage, and bone. Problems at this stage of development can cause birth defects such as choanal atresia (absent or closed passage), facial clefts and nasal dysplasia (faulty or incomplete development)[23] or extremely rarely polyrrhinia the formation of a duplicate nose.[24]

Normal development is critical because the newborn infant breathes through the nose for the first six weeks, and any nasal blockage will need emergency treatment to clear.[25]

Function

Respiration

Conchae shown in nasal cavity

The nose is the first organ of the upper respiratory tract in the respiratory system, and its main function is the supply and conditioning of inhaled air to the lungs. The nose is responsible for warming and moistening the air and providing its passage to the rest of the respiratory tract. Another function is to filter the air by removing particulates. The three positioned nasal conchae in each cavity provide four grooves as air passages, along which the air is circulated and moved to the nasopharynx.[8]

The nose is also able to provide sense information as to the temperature of the air being breathed, and is an important route for the administration of drugs.[26]

Nasal hair in the nostrils traps large particles preventing their entry into the lungs. Sneezing is an important reflex initiated by irritation of the nasal mucosa to expel unwanted particles through the mouth and nose. Photic sneezing is a reflex brought on by different stimuli such as bright lights.

Olfaction

The nose also plays the major part in the olfactory system. It contains an area of specialised cells, olfactory receptor neurons responsible for the sense of smell. The nasal conchae also help in olfaction function, by directing air-flow to the olfactory region.

Speech

Normal speech is produced with pressure from the lungs. This can be modified using airflow through the nose in a process called nasalisation. This involves the lowering of the soft palate to produce nasal vowels and consonants by allowing air to escape from both the nose and the mouth. Nasal airflow is also used to produce a variety of nasal clicks called click consonants. The paranasal sinuses act as sound chambers in vocal resonation.[27]

Clinical significance

One of the most common medical conditions involving the nose are nosebleeds (epistaxis). Most of them occur in Kiesselbach's plexus. Nasal congestion is a common symptom of infections or other inflammations of the nasal lining (rhinitis), such as in allergic rhinitis or vasomotor rhinitis (resulting from nasal spray abuse). Most of these conditions also cause anosmia, which is the medical term for a loss of smell. This may also occur in other conditions, for example following trauma, in Kallmann syndrome or Parkinson's disease.

In children the nose is a common site of foreign bodies.[28] The nose is susceptible to frostbite.

Because of the special nature of the blood supply to the human nose and surrounding area, it is possible for retrograde infections from the nasal area to spread to the brain. For this reason, the area from the corners of the mouth to the bridge of the nose, including the nose and maxilla, is known as the danger triangle of the face.

Specific systemic diseases, infections or other conditions that may result in destruction of part of the nose (for example, the nasal bridge, or nasal septal perforation) are rhinophyma, skin cancer (for example, basal cell carcinoma), granulomatosis with polyangiitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, syphilis, leprosy and exposure to cocaine, chromium or toxins. The nose may be stimulated to grow in acromegaly.

A common anatomic variant is an air-filled cavity within a concha known as a concha bullosa.[29] In rare cases a polyp can form inside a bullosa.[30] Usually a concha bullosa is small and without symptoms but when large can cause obstruction to sinus drainage.[31]

Chronic nasal obstruction resulting in breathing through the mouth can greatly impair or prevent the nostrils from flaring.[32] One of the causes of snoring is nasal obstruction,[33] and anti-snoring devices such as a nasal strip help to flare the nostrils and keep the airway open.

The surgical procedure to correct breathing problems due to disorders in the nasal structures is called a rhinoplasty, and this is also the procedure used for a cosmetic surgery when it is commonly called a "nose job". For surgical procedures of rhinoplasty the nose is mapped out into a number of subunits and segments. This uses nine aesthetic nasal subunits and six aesthetic nasal segments. A septoplasty is the specific surgery to correct a nasal septum deviation.

Some drugs can be nasally administered, and these include nasal sprays and topical treatments.

Society and culture

Some people choose to have cosmetic surgery called a rhinoplasty, to change the appearance of their nose. Nose piercings are also common, such as in the nostril, septum, or bridge.

In New Zealand, nose pressing ("hongi") is a traditional greeting originating among the Māori people.[34] However it is now generally confined to certain traditional celebrations.[35]

The Hanazuka monument enshrines the mutilated noses of at least 38,000 Koreans killed during the Japanese invasions of Korea from 1592 to 1598.[36]

The septal cartilage can be destroyed through repeated nasal inhalation of drugs such as cocaine. This in turn can lead to more widespread collapse of the nasal skeleton.

Nose-picking is a common, mildly taboo habit. Medical risks include the spread of infections, nosebleeds and, rarely, perforation of the nasal septum. When it becomes compulsive it is termed rhinotillexomania. The wiping of the nose with the hand, commonly referred to as the "allergic salute", is also mildly taboo and can result in the spreading of infections as well. Habitual as well as fast or rough nose wiping may also result in a crease (known as a transverse nasal crease or groove) running across the nose, and can lead to permanent physical deformity observable in childhood and adulthood.[37][38]

Nose fetishism (or nasophilia) is the sexual partialism for the nose.

In certain Asian countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Thailand and Bangladesh rhinoplasty is common to create a more developed nose bridge or "high nose".[39] Similarly, "DIY nose lifts" in the form of re-usable cosmetic items have become popular and are sold in many Asian countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Sri Lanka and Thailand.[40][41][42] A high-bridged nose has been a common beauty ideal in many Asian cultures dating back to the beauty ideals of ancient China and India.[43][44]

Evolutionary hypotheses

Neanderthals

Clive Finlayson of the Gibraltar Museum said the large Neanderthal noses were an adaption to the cold,[45] Todd C. Rae of the American Museum of Natural History said primate and arctic animal studies have shown sinus size reduction in areas of extreme cold rather than enlargement in accordance with Allen's rule.[46] Therefore, Todd C. Rae concludes that the design of the large and prognathic Neanderthal nose was evolved for the hotter climate of the Middle East and was kept when the Neanderthals entered Europe.[46]

Miquel Hernández of the Department of Animal Biology at the University of Barcelona said the "high and narrow nose of Eskimos" and "Neanderthals" is an "adaption to a cold and dry environment", since it contributes to warming and moisturizing the air and the "recovery of heat and moisture from expired air".[47]

Humans

An article published in the speculative journal Medical Hypotheses suggested that the nose is an alteration of the angle of skull following human skeletal changes due to bipedalism. This changed the shape of the skull base causing, together with change in diet, a knock-on morphological reduction in the relative size of the maxillary and mandible and through this a "squeezing" of the protrusion of the most anterior parts of the face more forward and so increasing nose prominence and modifying its shape.[48]

The aquatic ape hypothesis relates the nose to a hypothesized period of aquatic adaptation in which the downward-facing nostrils and flexible philtrum prevented water from entering the nasal cavities.[49] The theory is not generally accepted by mainstream scholars of human evolution.[50]

Neoteny

Grecian nose

Stephen Jay Gould has noted that larger noses are less neotenous, especially the large Grecian nose.[51] Women have smaller noses than men due to not having increased secretion of testosterone in adolescence.[5] Smaller noses, along with other neotenous features such as large eyes and full lips, are generally considered more attractive on women.[52]Werner syndrome, a condition that causes the appearance of premature aging, causes a "bird-like" appearance due to pinching of the nose[53] while, conversely, Down syndrome, a neotenizing condition, causes a flattening of the nose.[54]

See also

Empty nose syndrome, a nose crippled by excessive resection of the inferior and/or middle turbinates of the nose- Nasal cycle

- Nasothek

Neti (Hatha Yoga), an Ayurvedic technique of nasal cleansing

Sròn, the Scottish Gaelic word for nose and the name of some hills in the Scottish Highlands

References

^ Knipe, Henry. "Anterior nasal spine fracture | Radiology Case | Radiopaedia.org". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 24 October 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Glossary: nasal spine (anterior)". ArchaeologyInfo.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-01. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

^ ab Moore, Keith; Dalley, Arthur; Agur, Anne (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (Eighth ed.). Wolters Kluwer. pp. 963–968. ISBN 9781496347213.

^ ab Tortora, G; Anagnostakos, N (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (5th. Harper international ed.). Harper & Row. p. 556. ISBN 978-0063507296.

^ ab "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-11-30. Retrieved 2007-06-18.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "Paranasal Sinus Anatomy: Overview, Gross Anatomy, Microscopic Anatomy". 5 April 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

^ abc Van Cauwenberge, P; Sys, L; De Belder, T; Watelet, JB (February 2004). "Anatomy and physiology of the nose and the paranasal sinuses". Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America. 24 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1016/S0889-8561(03)00107-3. PMID 15062424.

^ Betlejewski, S; Betlejewski, A (2008). "[The influence of nasal flow aerodynamics on the nasal physiology]". Otolaryngologia Polska = the Polish Otolaryngology. 62 (3): 321–5. doi:10.1016/S0030-6657(08)70263-4. PMID 18652158.

^ Becker, DG; Becker, SS (2003). "Treatment of nasal obstruction from nasal valve collapse with alar batten grafts". Journal of Long-term Effects of Medical Implants. 13 (3): 259–69. PMID 14516189.

^ Pecorari, G; Riva, G; Bianchi, FA; Cavallo, G; Revello, F; Bironzo, M; Verzè, L; Garzaro, M; Ramieri, G (1 September 2017). "The effect of closed septorhinoplasty on nasal functions and on external and internal nasal valves: A prospective study". American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy. 31 (5): 323–327. doi:10.2500/ajra.2017.31.4459. PMID 28859710.

^ Duron, JB; Nguyen, PS; Jallut, Y; Bardot, J; Aiach, G (December 2014). "[Middle third of the nose and internal valve. Alar wall and external valve]". Annales de Chirurgie Plastique et Esthetique. 59 (6): 508–21. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2014.06.010. PMID 25086817.

^ Fischer, H; Gubisch, W (November 2006). "Nasal valves--importance and surgical procedures". Facial Plastic Surgery : FPS. 22 (4): 266–80. doi:10.1055/s-2006-954845. PMID 17131269.

^ Wolfram-Gabel, R; Sick, H (February 2002). "Microvascularization of the mucocutaneous junction of the nose". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy : SRA. 24 (1): 27–32. PMID 12197007.

^ ab Wagenmann, M; Naclerio, RM (September 1992). "Anatomic and physiologic considerations in sinusitis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 90 (3 Pt 2): 419–23. PMID 1527330.

^ Bal, M; Berkiten, G; Uyanık, E (July 2014). "Mucous retention cysts of the paranasal sinuses". Hippokratia. 18 (4): 379. PMC 4453822. PMID 26052215.

^ "Medical Definition of leptorrhine". www.merriam-webster.com.

^ Roe, J. O. (1 February 1989). "The Deformity Termed 'Pug Nose' and Its Correction by a Simple Operation". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 115 (2): 156–157. doi:10.1001/archotol.1989.01860260030010.

^ Schreiber, BE; Twigg, S; Marais, J; Keat, AC (April 2014). "Saddle-nose deformities in the rheumatology clinic". Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal. 93 (4–5): E45–7. PMID 24817241.

^ Sonek, JD; Cicero, S; Neiger, R; Nicolaides, KH (November 2006). "Nasal bone assessment in prenatal screening for trisomy 21". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 195 (5): 1219–30. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.042. PMID 16615922.

^ Persico, N; et al. (March 2012). "Nasal bone assessment in fetuses with trisomy 21 at 16-24 weeks of gestation by three-dimensional ultrasound". Prenatal Diagnosis. 32 (3): 240–4. doi:10.1002/pd.2938. PMID 22430721.CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

^ Chiu, TW; Shaw-Dunn, J; McGarry, GW (October 2008). "Woodruff's plexus". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 122 (10): 1074–7. doi:10.1017/S002221510800176X. PMID 18289456.

^ Hengerer AS, Oas RE (1987). Congenital Anomalies of the Nose: Their Embryology, Diagnosis, and Management (SIPAC). Alexandria VA: American Academy of Otolaryngology.

[page needed]

^ "Polyrrhinia (Concept Id: C4274730) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

^ Nasal Anatomy at eMedicine

^ Jones, N (23 September 2001). "The nose and paranasal sinuses physiology and anatomy". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 51 (1–3): 5–19. PMID 11516776.

^ Tortora, G; Anagnostakos, N (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (5th. Harper international ed.). Harper & Row. p. 144. ISBN 978-0063507296.

^ "Foreign Body, Nose". Archived from the original on 2008-12-20. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

^ Cukurova, I; Yaz, A; Gumussoy, M; Yigitbasi, OG; Karaman, Y (26 March 2012). "A patient presenting with concha bullosa in another concha bullosa: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 6: 87. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-6-87. PMC 3338398. PMID 22448660.

^ Erkan, AN; Canbolat, T; Ozer, C; Yilmaz, I; Ozluoglu, LN (8 May 2006). "Polyp in concha bullosa: a case report and review of the literature". Head & Face Medicine. 2: 11. doi:10.1186/1746-160X-2-11. PMC 1471777. PMID 16681852.

^ Rodrigo Tapia, JP; Alvarez Alvarez, I; Casas Rubio, C; Blanco Mercadé, A; Díaz Villarig, JL (August 1999). "[A giant bilateral concha bullosa causing nasal obstruction]". Acta Otorrinolaringologica Espanola. 50 (6): 490–2. PMID 10502705.

^ Moore, Keith; Dalley, Arthur; Agur, Anne (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (Eighth ed.). Wolters Kluwer. pp. 864–869. ISBN 9781496347213.

^ ""Snoring Causes". Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic. 26 April 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

^ Derby, Mark (September 2013). "Ngā mahi tika". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

^ "Greetings! Hongi Style! – polynesia.com | blog". polynesia.com | blog. 2016-03-24. Archived from the original on 2017-09-18. Retrieved 2017-09-18.

^ Sansom, George Bailey (1961). A History of Japan, 1334–1615. Stanford studies in the civilizations of eastern Asia. Stanford University Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-8047-0525-7.Visitors to Kyoto used to be shown the Minizuka or Ear Tomb, which contained, it was said, the noses of those 38,000, sliced off, suitably pickled, and sent to Kyoto as evidence of victory.

^ Pray, W. Steven (2005). Nonprescription Product Therapeutics. p. 221: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0781734981.

^ Mitali Ruths (June 14, 2011). "White Line on Nose in Children". LiveStrong.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-22. Retrieved 2012-11-25.

^ "Miss Universe Malaysia pageant contestants 'look too western'". 2018-11-28. Archived from the original on 2016-09-22.

^ Strochlic, Nina (6 January 2014). "DIY Plastic Surgery: Can You Change Your Face Without Going Under the Knife?". The Daily Beast.

^ "Connecting People Through News". PressReader. Archived from the original on 2017-12-06.

^ "Nose Shaper". Shybuy. Archived from the original on 2017-06-05.

^ Marc S. Abramson (2011). Ethnic Identity in Tang China. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8122-0101-7. Archived from the original on 2018-05-02.

^ Johann Jakob Meyer (1989). Sexual Life in Ancient India: A Study in the Comparative History of Indian Culture. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 433. ISBN 978-81-208-0638-2. Archived from the original on 2018-05-02.

^ Finlayson, C (2004). Neanderthals and modern humans: an ecological and evolutionary perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84. ISBN 978-0-521-82087-5.

^ ab Rae, T.C. (2011). "The Neanderthal face is not cold adapted". Journal of Human Evolution. 60 (2): 234–239. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.10.003. PMID 21183202.

^ Hernández, M.; Fox, C. L.; Garcia-Moro, C. (1997). "Fueguian cranial morphology: The adaptation to a cold, harsh environment". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 103 (1): 103–117. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199705)103:1<103::AID-AJPA7>3.0.CO;2-X. PMID 9185954.

^ Mladina, R; Skitarelić N; Vuković K (2009). "Why do humans have such a prominent nose? The final result of phylogenesis: a significant reduction of the splanchocranium on account of the neurocranium". Med Hypotheses. 73 (3): 280–3. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2009.03.045. PMID 19442453.

^ Morgan, Elaine (1997). The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis. Souvenir Press. ISBN 978-0-285-63518-0.

^ Meier, R (2003). The complete idiot's guide to human prehistory. Alpha Books. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0-02-864421-9.

^ Gould, S.J. (1996). The mismeasure of man. Norton and Company: NY.[page needed]

^ Jones, Doug (1995). "Sexual Selection, Physical Attractiveness, and Facial Neoteny: Cross-cultural Evidence and Implications". Current Anthropology. 36 (5): 723–48. doi:10.1086/204427. JSTOR 2744016.

^ Oshima J, Martin GM, Hisama FM (2002-12-02) [Updated 2016-09-29]. Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., eds. "Werner Syndrome". GeneReviews®. Seattle, WA: University of Washington. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2017-08-31 – via NCBI.

^ Opitz, John M.; Gilbert-Barness, Enid F. (2005). "Reflections on the pathogenesis of Down syndrome". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 37: 38–51. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320370707. PMID 2149972.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Human noses. |

| Look up WikiSaurus:nose in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- From the Nose to the Eustachian Tube: Information, videos, tips for diving

- Your Nose: The Guardian Of Your Lungs