Hafez al-Assad

Field Marshal Hafez al-Assad | |

|---|---|

حافظ الأسد | |

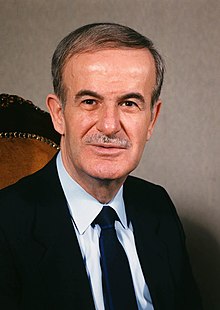

Assad in 1987 | |

| 18th President of Syria | |

In office 12 March 1971 – 10 June 2000 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself Abdul Rahman Khleifawi Mahmoud al-Ayyubi Abdul Rahman Khleifawi Muhammad Ali al-Halabi Abdul Rauf al-Kasm Mahmoud Zuabi Muhammad Mustafa Mero |

| Vice President | Mahmoud al-Ayyubi Rifaat al-Assad Abdul Halim Khaddam |

| Preceded by | Ahmad al-Khatib |

| Succeeded by | Abdul Halim Khaddam (Acting) |

| Prime Minister of Syria | |

In office 21 November 1970 – 3 April 1971 | |

| President | Ahmad al-Khatib Himself |

| Preceded by | Nureddin al-Atassi |

| Succeeded by | Abdul Rahman Khleifawi |

| Regional Secretary of the Regional Command of the Syrian Regional Branch | |

In office 18 November 1970 – 10 June 2000 | |

| Deputy | Mohamad Jaber Bajbouj Zuhair Masharqa Sulayman Qaddah |

| Preceded by | Nureddin al-Atassi |

| Succeeded by | Bashar al-Assad |

| Secretary General of the National Command of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party | |

In office 12 September 1971 – 10 June 2000 | |

| Deputy | Abdullah al-Ahmar |

| Preceded by | Nureddin al-Atassi |

| Succeeded by | Abdullah al-Ahmar (de facto; al-Assad is still de jure Secretary General, even though he is dead.) |

| Minister of Defense | |

In office 23 February 1966 – 1972 | |

| President | Nureddin al-Atassi Ahmad al-Khatib Himself |

| Prime Minister | Yusuf Zuaiyin Nureddin al-Atassi Himself Abdul Rahman Kleifawi |

| Preceded by | Muhammad Umran |

| Succeeded by | Mustafa Tlass |

| Member of the Regional Command of the Syrian Regional Branch | |

In office 27 March 1966 – 10 June 2000 | |

In office 5 September 1963 – 4 April 1965 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1930-10-06)6 October 1930 Qardaha, Alawite State, French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon |

| Died | 10 June 2000(2000-06-10) (aged 69) Damascus, Syria |

| Resting place | Qardaha, Syria |

| Political party | Ba'ath Party (Syrian faction) (since 1966) |

| Other political affiliations | Arab Ba'ath Party (1946–47) Ba'ath Party (1947–66) |

| Spouse(s) | Anisa Makhlouf (1957–2000) |

| Relations | Jamil, Rifaat (brothers) |

| Children | Bushra, Bassel, Bashar, Majd, Maher |

| Parents | Ali Sulayman al-Assad Na'sa al-Assad |

| Alma mater | Homs Military Academy |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | Syrian Air Force Syrian Armed Forces |

| Years of service | 1952–2000 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Syrian Air Force Syrian Armed Forces |

| Battles/wars | Six-Day War (1967) War of Attrition (1967–70) Black September (1970–71) |

Hafez al-Assad (Arabic: حافظ الأسد Ḥāfiẓ al-ʾAsad, Levantine pronunciation: Arabic pronunciation: [ˈħaːfezˤ elˈʔasad] Modern Standard Arabic: [ħaːfɪðˤ al'ʔasad]; 6 October 1930 – 10 June 2000) was a Syrian politician who served as President of Syria from 1971 to 2000. He was also Prime Minister from 1970 to 1971, as well as Regional Secretary of the Regional Command of the Syrian Regional Branch of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party and Secretary General of the National Command of the Ba'ath Party from 1970 to 2000.

Assad participated in the 1963 Syrian coup d'état which brought the Syrian Regional Branch of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party to power, and the new leadership appointed him Commander of the Syrian Air Force. In 1966, Assad participated in a second coup, which toppled the traditional leaders of the Ba'ath Party and brought a radical military faction headed by Salah Jadid to power. Assad was appointed defense minister by the new government. Four years later, Assad initiated a third coup which ousted Jadid, and appointed himself as the undisputed leader of Syria.

Assad de-radicalised the Ba'ath government when he took power by giving more space to private property and by strengthening the country's foreign relations with countries which his predecessor had deemed reactionary. He sided with the Soviet Union during the Cold War in turn for support against Israel, and, while he had forsaken the pan-Arab concept of unifying the Arab world into one Arab nation, he sought to make Syria the defender of Arab interests against Israel. When he came to power, Assad organised state services along sectarian lines (the Sunnis became the heads of political institutions, while the Alawites took control of the military, intelligence, and security apparatuses). The formerly collegial powers of Ba'athist decision-making were curtailed, and were transferred to the Syrian presidency. The Syrian government ceased to be a one-party system in the normal sense of the word, and was turned into a one-party state with a strong presidency. To maintain this system, a cult of personality centered on Assad and his family was created by the president and Ba'ath party.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Having become the main source of initiative inside the Syrian government, Assad began looking for a successor. His first choice was his brother Rifaat, but Rifaat attempted to seize power in 1983–84 when Hafez's health was in doubt. Rifaat was subsequently exiled when Hafez's health recovered. Hafez's next choice of successor was his eldest son, Bassel. However Bassel died in a car accident in 1994, and Hafez turned to his third choice—his younger son Bashar, who at that time had no political experience. This move was met with criticism within some quarters of the Syrian ruling class, but Assad persisted with his plan and demoted several officials who opposed this succession. Hafez died in 2000 and Bashar succeeded him as President.

Contents

1 Early life and education: 1930–1950

1.1 Family

1.2 Education and early political career

2 Air Force career: 1950–1958

3 Runup to 1963 coup: 1958–1963

4 Early Ba'ath Party rule: 1963–1970

4.1 Aflaqite leadership: 1963–1966

4.1.1 Military work

4.1.2 Power struggle and 1966 coup

4.2 Jadid as strongman: 1966–1970

4.2.1 Beginning

4.2.2 Seizing power

4.2.2.1 Differences with Jadid

4.2.2.2 "Duality of power"

4.2.2.3 1970 coup d'état

5 Presidency: 1970–2000

5.1 Domestic events and policies

5.1.1 Consolidating power

5.1.2 Institutionalization

5.1.2.1 Sectarianism

5.1.3 Islamist uprising

5.1.3.1 Background

5.1.3.2 Events

5.1.4 1983–1984 succession crisis

5.1.5 Autocracy, succession and death

5.1.6 Economy

5.2 Foreign policy

5.2.1 Yom Kippur War

5.2.1.1 Planning

5.2.1.2 The war

5.2.2 Lebanese Civil War

6 References

7 External links

Early life and education: 1930–1950

Family

Hafez was born on 6 October 1930 in Qardaha to an Alawite family[7] of the Kalbiyya tribe.[8][9] His parents were Na'sa and Ali Sulayman al-Assad.[10] Hafez was Ali's ninth son, and the fourth from his second marriage.[10] Sulayman married twice, had eleven children[11] and was known for his strength and shooting abilities; locals nicknamed him Wahhish (wild beast).[12] By the 1920s he was respected locally, and like many others he initially opposed the French Mandate for Syria.[13] Nevertheless, Ali Sulayman later cooperated with the French administration and was appointed to an official post.[14] For his accomplishments he was called "al-Assad" (a lion) by local residents[13] and in 1927 made the nickname his surname.[15] in 1936, he was one of 80 Alawite notables who signed a letter addressed to the French Prime Minister saying that "[the] Alawi people rejected attachment to Syria and wished to stay under French protection."[14]

Education and early political career

Alawites initially opposed a united Syrian state (since they thought their status as a religious minority would endanger them),[16] and Hafez's father shared this belief.[16] As the French left Syria, many Syrians mistrusted Alawites because of their alignment with France.[16] Hafez left his Alawite village, beginning his education at age nine in Sunni-dominated[7]Latakia.[15] He was the first in his family to attend high school,[17] but in Latakia Assad faced Sunni anti-Alawite bias.[16] He was an excellent student, winning several prizes at about age 14.[16] Assad lived in a poor, predominantly Alawite part of Latakia;[18] to fit in, he approached political parties that welcomed Alawites.[18] These parties (which also espoused secularism) were the Syrian Communist Party, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) and the Arab Ba'ath Party; Assad joined the latter in 1946,[18] and some of his friends belonged to the SSNP.[19] The Ba'ath (Renaissance) Party espoused a pan-Arabist, socialist ideology.[18]

Assad was an asset to the party, organizing Ba'ath student cells and carrying the party's message to the poor sections of Latakia and Alawite villages.[15] He was opposed by the Muslim Brotherhood, which was allied with wealthy and conservative Muslim families.[15] His high school accommodated students from rich and poor families,[15] and Assad was joined by poor, anti-establishment Sunni Muslim youth from the Ba'ath Party in confrontations with students from wealthy Brotherhood families.[15] He made many Sunni friends, some of whom later became his political allies.[15] While still a teenager, Assad became increasingly prominent in the party[20] as an organizer and recruiter, head of his school's student-affairs committee from 1949 to 1951 and president of the Union of Syrian Students.[15] During his political activism in school, he met many men who would serve him when he was president.[20]

Air Force career: 1950–1958

Hafez al-Assad (above) standing on the wing of a Fiat G.46-4B with fellow cadets at the Syrian AF Academy outside Aleppo, 1951–52

After graduating from high school, Assad aspired to be a medical doctor, but his father could not pay for his study at the Jesuit University of St. Joseph in Beirut.[15] Instead, in 1950 he decided to join the Syrian Armed Forces.[20] Assad entered the military academy in Homs, which offered free food, lodging and a stipend.[15] He wanted to fly, and entered the flying school in Aleppo in 1950.[21][22] Assad graduated in 1955, after which he was commissioned a lieutenant in the Syrian Air Force.[23] Upon graduation from flying school he won a best-aviator trophy,[21][22] and shortly afterwards was assigned to the Mezze air base near Damascus.[24] In his early 20s, he married Anisa Makhlouf in 1957, a distant relative of a powerful family.[25]

In 1954, the military split in a revolt against President Adib Shishakli.[26]Hashim al-Atassi, head of the National Bloc and briefly president after Sami al-Hinnawi's coup, returned as president and Syria was again under civilian rule.[26] After 1955, Atassi's hold on the country was increasingly shaky.[26] As a result of the 1955 election Atassi was replaced by Shukri al-Quwatli, who was president before Syria's independence from France.[26] The Ba'ath Party grew closer to the Communist Party not because of shared ideology, but a shared opposition to the West.[26] At the academy Assad met Mustafa Tlass, his future minister of defense.[27] In 1955, Assad was sent to Egypt for a further six months of training.[28] When Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal in 1956, Syria feared retaliation from the United Kingdom, and Assad flew in an air-defense mission.[29] He was among the Syrian pilots who flew to Cairo to show Syria's commitment to Egypt.[28] After finishing a course in Egypt the following year, Assad returned to a small air base near Damascus.[28] During the Suez Crisis, he also flew a reconnaissance mission over northern and eastern Syria.[28] In 1957, as squadron commander, Assad was sent to the Soviet Union for training in flying MiG-17s.[21] He spent ten months in the Soviet Union, during which he fathered a daughter (who died as an infant while he was abroad) with his wife.[25]

In 1958 Syria and Egypt formed the United Arab Republic (UAR), separating themselves from Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey (who were aligned with the United Kingdom).[30] This pact led to the rejection of Communist influence in favor of Egyptian control over Syria.[30] All Syrian political parties (including the Ba'ath Party) were dissolved, and senior officers—especially those who supported the Communists—were dismissed from the Syrian armed forces.[30] Assad, however, remained in the army and rose quickly through the ranks.[30] After reaching the rank of captain he was transferred to Egypt, continuing his military education with future president of Egypt Hosni Mubarak.[21]

Runup to 1963 coup: 1958–1963

Assad was not content with a professional military career, regarding it as a gateway to politics.[31] After the creation of the UAR, Ba'ath Party leader Michel Aflaq was forced by Nasser to dissolve the party.[31] During the UAR's existence, the Ba'ath Party experienced a crisis[32] for which several of its members—mostly young—blamed Aflaq.[33] To resurrect the Syrian Regional Branch of the party, Muhammad Umran, Salah Jadid, Assad and others established the Military Committee.[33] In 1957–58 Assad rose to a dominant position in the Military Committee, which mitigated his transfer to Egypt.[21] After Syria left the UAR in September 1961, Assad and other Ba'athist officers were removed from the military by the new government in Damascus, and he was given a minor clerical position at the Ministry of Transport.[21]

Assad played a minor role in the failed 1962 military coup, for which he was jailed in Lebanon and later repatriated.[34] That year, Aflaq convened the 5th National Congress of the Ba'ath Party (where he was reelected as the Secretary General of the National Command) and ordered the re-establishment of the party's Syrian Regional Branch.[35] At the Congress, the Military Committee (through Umran) established contacts with Aflaq and the civilian leadership.[35] The committee requested permission to seize power by force, and Aflaq agreed to the conspiracy.[35] After the success of the Iraqi coup d'état led by the Ba'ath Party's Iraqi Regional Branch, the Military Committee hastily convened to launch a Ba'athist military coup in March 1963 against President Nazim al-Kudsi[36] (which Assad helped plan).[34][37] The coup was scheduled for 7 March, but he announced a postponement (until the next day) to the other units.[38] During the coup Assad led a small group to capture the Dumayr air base, 40 kilometres (25 mi) northeast of Damascus.[39] His group was the only one that encountered resistance.[39] Some planes at the base were ordered to bomb the conspirators, and because of this Assad hurried to reach the base before dawn.[39] Because the 70th Armored Brigade's surrender took longer than anticipated, however, he arrived in broad daylight.[39] When Assad threatened the base commander with shelling, the commander negotiated a surrender;[39] Assad later claimed that the base could have withstood his forces.[39]

Early Ba'ath Party rule: 1963–1970

Aflaqite leadership: 1963–1966

Military work

Not long after Assad's election to the Regional Command, the Military Committee ordered him to strengthen the committee's position in the military establishment.[40] Assad may have received the most important job of all, since his primary goal was to end factionalism in the Syrian military and make it a Ba'ath monopoly;[40] as he said, he had to create an "ideological army".[40] To help with this task Assad recruited Zaki al-Arsuzi, who indirectly (through Wahib al-Ghanim) inspired him to join the Ba'ath Party when he was young.[40] Arsuzi accompanied Assad on tours of military camps, where Arsuzi lectured the soldiers on Ba'athist thought.[40] In gratitude for his work, Assad gave Arsuzi a government pension.[40] Assad continued his Ba'athification of the military by appointing loyal officers to key positions and ensuring that the "political education of the troops was not neglected".[41] He demonstrated his skill as a patient planner during this period.[41] As Patrick Seale wrote, Assad's mastery of detail "suggested the mind of an intelligence officer".[41]

Assad was promoted to major and then to lieutenant colonel, and by the end of 1963 was in charge of the Syrian Air Force.[37] By the end of 1964 he was named commander of the Air Force, with the rank of major general.[37] Assad gave privileges to Air Force officers, appointed his confidants to senior and sensitive positions and established an efficient intelligence network.[42] Air Force Intelligence, under the command of Muhammad al-Khuli, became independent of Syria's other intelligence organizations and received assignments beyond Air Force jurisdiction.[42] Assad prepared himself for an active role in the power struggles that lay ahead.[42]

Power struggle and 1966 coup

In the aftermath of the 1963 coup, at the First Regional Congress (held 5 September 1963) Assad was elected to the Syrian Regional Command (the highest decision-making body in the Syrian Regional Branch).[43] While not a leadership role, it was Assad's first appearance in national politics;[43] in retrospect, he said he positioned himself "on the left" in the Regional Command.[43]Khalid al-Falhum, a Palestinian who would later work for the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), met Assad in 1963; he noted that Assad was a strong leftist "but was clearly not a communist", committed instead to Arab nationalism.[44]

During the 1964 Hama riot, Assad voted to suppress the uprising violently if needed.[45] The decision to suppress the Hama riot led to a schism in the Military Committee between Umran and Jadid.[46] Umran opposed force, instead wanting the Ba'ath Party to create a coalition with other pan-Arab forces.[46] Jadid desired a strong one-party state, similar to those in the communist countries of Europe.[46] Assad, as junior partner, kept quiet at first but eventually allied himself with Jadid.[46] Why Assad chose to side with him has been widely discussed; he probably shared Jadid's radical ideological outlook.[47] Having lost his footing on the Military Committee, Umran aligned himself with Aflaq and the National Command; he told them that the Military Committee was planning to seize power in the party by ousting them.[47] Because of Umran's defection, Rifaat al-Assad (Assad's brother) succeeded Umran as commander of a secret military force tasked with protecting Military Committee loyalists.[47]

In its bid to seize power the Military Committee allied themselves with the regionalists, a group of cells in the Syrian Regional Branch that refused to disband in 1958 when ordered to do so.[48] Although Aflaq considered these cells traitors, Assad called them the "true cells of the party"; this again highlighted differences between the Military Committee and the National Command headed by Aflaq.[48] At the Eighth National Congress in 1965 Assad was elected to the National Command, the party's highest decision-making body.[49] From his position as part of the National Command, Assad informed Jadid on its activities.[50] After the congress, the National Command dissolved the Syrian Regional Command; Aflaq proposed Salah al-Din al-Bitar as prime minister, but Assad and Brahim Makhous opposed Bitar's nomination.[51] According to Seale, Assad abhorred Aflaq; he considered him an autocrat and a rightist, accusing him of "ditching" the party by ordering the dissolution of the Syrian Regional Branch in 1958.[31] Assad, who also disliked Aflaq's supporters, nevertheless opposed a show of force against the Aflaqites.[52] In response to the imminent coup Assad, Naji Jamil, Husayn Mulhim and Yusuf Sayigh left for London.[53]

In the 1966 Syrian coup d'état, the Military Committee overthrew the National Command.[42] The coup led to a permanent schism in the Ba'ath movement, the advent of neo-Ba'athism and the establishment of two centers of the international Ba'athist movement: one Iraqi- and the other Syrian-dominated.[54]

Jadid as strongman: 1966–1970

Beginning

After the coup, Assad was appointed Minister of Defense.[55] This was his first cabinet post, and through his position he would be thrust into the forefront of the Syrian–Israeli conflict.[55] His government was radically socialist, and sought to remake society from top to bottom.[55] Although Assad was a radical, he opposed the headlong rush for change.[55] Despite his title, he had little power in the government and took more orders than he issued.[55] Jadid was the undisputed leader at the time, opting to remain in the office of Assistant Regional Secretary of the Syrian Regional Command instead of taking executive office (which had historically been held by Sunnis).[56]Nureddin al-Atassi was given three of the four top executive positions in the country: President, Secretary-General of the National Command and Regional Secretary of the Syrian Regional Command.[56] The post of prime minister was given to Yusuf Zu'ayyin.[56] Jadid (who was establishing his authority) focused on civilian issues and gave Assad de facto control of the Syrian military, considering him no threat.[56]

During the failed coup d'état of late 1966, Salim Hatum tried to overthrow Jadid's government.[57] Hatum (who felt snubbed when he was not appointed to the Regional Command after the February 1966 coup d'état) sought revenge and the return to power of Hammud al-Shufi, the first Regional Secretary of the Regional Command after the Syrian Regional Branch's re-establishment in 1963.[57] When Jadid, Atassi and Regional Command member Jamil Shayya visited Suwayda, forces loyal to Hatum surrounded the city and captured them.[58] In a twist of fate, the city's Druze elders forbade the murder of their guests and demanded that Hatum wait.[58] Jadid and the others were placed under house arrest, with Hatum planning to kill them at his first opportunity.[58] When word of the mutiny spread to the Ministry of Defense, Assad ordered the 70th Armored Brigade to the city.[58] By this time Hatum, a Druze, knew that Assad would order the bombardment of Suwayda (a Druze-dominated city) if Hatum did not accede to his demands.[58] Hatum and his supporters fled to Jordan, where they were given asylum.[59] How Assad learned about the conspiracy is unknown, but Mustafa al-Hajj Ali (head of Military Intelligence) may have telephoned the Ministry of Defense.[59] Due to his prompt action, Assad earned Jadid's gratitude.[59]

In the aftermath of the attempted coup Assad and Jadid purged the party's military organization, removing 89 officers; Assad removed an estimated 400 officers, Syria's largest military purge to date.[59] The purges, which began when the Ba'ath Party took power in 1963, had left the military weak.[59] As a result, when the Six-Day War broke out, Syria had no chance of victory.[59]

Seizing power

The Arab defeat in the Six-Day War, in which Israel captured the Golan Heights from Syria, provoked a furious quarrel among Syria's leadership.[60] The civilian leadership blamed military incompetence, and the military responded by criticizing the civilian leadership (led by Jadid).[60] Several high-ranking party members demanded Assad's resignation, and an attempt was made to vote him out of the Regional Command, the party's highest decision-making body.[60] The motion was defeated by one vote, with Abd al-Karim al-Jundi (who the anti-Assad members hoped would succeed Assad as defense minister) voting, as Patrick Seale put it, "in a comradely gesture" to retain him.[60] During the end of the war, the party leadership freed Aflaqites Umran, Amin al-Hafiz and Mansur al-Atrash from prison.[60] Shortly after his release, Hafiz was approached by dissident Syrian military officers to oust the government; he refused, believing that a coup at that time would have helped Israel, but not Syria.[60]

The war was a turning point for Assad (and Ba'athist Syria in general),[61] and his attempted ouster began a power struggle with Jadid for control of the country.[61] Until then Assad had not shown ambition for high office, arousing little suspicion in others.[61] From the 1963 Syrian coup d'état to the Six-Day War in 1967, Assad did not play a leading role in politics and was usually overshadowed by his contemporaries.[62] As Patrick Seale wrote, he was "apparently content to be a solid member of the team without the aspiration to become number one".[62] Although Jadid was slow to see Assad's threat, shortly after the war Assad began developing a network in the military and promoted friends and close relatives to high positions.[62]

Differences with Jadid

Assad believed that Syria's defeat in the Six-Day War was Jadid's fault, and the accusations against himself were unjust.[62] By this time Jadid had total control of the Regional Command, whose members supported his policies.[62] Assad and Jadid began to differ on policy;[62] Assad believed that Jadid's policy of a people's war (an armed-guerrilla strategy) and class struggle had failed Syria, undermining its position.[62] Although Jadid continued to champion the concept of a people's war even after the Six-Day War, Assad opposed it. He felt that the Palestinian guerrilla fighters had been given too much autonomy and had raided Israel constantly, which in turn sparked the war.[62] Jadid had broken diplomatic relations with countries he deemed reactionary, such as Saudi Arabia and Jordan.[62] Because of this, Syria did not receive aid from other Arab countries. Egypt and Jordan, who participated in the war, received £135 million per year for an undisclosed period.[62]

While Jadid and his supporters prioritised socialism and the "internal revolution", Assad wanted the leadership to focus on foreign policy and the containment of Israel.[63] The Ba'ath Party was divided over several issues, such as how the government could best use Syria's limited resources, the ideal relationship between the party and the people, the organization of the party and whether the class struggle should end.[63] These subjects were discussed heatedly in Ba'ath Party conclaves, and when they reached the Fourth Regional Congress the two sides were irreconcilable.[63]

Assad wanted to "democratize" the party by making it easier for people to join.[64] Jadid was wary of too large a membership, believing that the majority of those who joined were opportunists.[63] Assad, in an interview with Patrick Seale in the 1980s, stated that such a policy would make Party members believe they were a privileged class.[64] Another problem, Assad believed, was the lack of local-government institutions.[64] Under Jadid, there was no governmental level below the Council of Ministers (the Syrian government).[64] When the Ba'athist Iraqi Regional Branch (which continued to support the Aflaqite leadership) took control of Iraq in the 17 July Revolution, Assad was one of the few high-level politicians wishing to reconcile with them;[64] he called for the establishment of an "Eastern Front" with Iraq against Israel in 1968.[65] Jadid's foreign policy towards the Soviet Union was also criticised by Assad, who believed it had failed.[65] In many ways the relationship between the countries was poor, with the Soviets refusing to acknowledge Jadid's scientific socialism and Soviet newspapers calling him a "hothead".[66] Assad, on the contrary, called for greater pragmatism in decision-making.[66]

"Duality of power"

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

—General Fu'ad Kallas on the importance in which Assad laid on personal loyalty[67]

The conflict between Assad and Jadid became the talk of the army and the party, with a "duality of power" noted between them.[66] Shortly after the failed attempt to expel Assad from the Regional Command, he began to consolidate his position in the military establishment[66]—for example, by replacing Chief of Staff Ahmad al-Suwaydani with his friend Mustafa Tlass.[66] Although Suwaydani's relationship with Jadid had deteriorated, he was removed because of his complaints about "Alawi influence in the army".[66] Tlass was later appointed Assad's Deputy Minister of Defense (his second-in-command).[67] Others removed from their positions were Ahmad al-Mir (a founder and former member of the Military Committee, and former commander of the Golan Front) and Izzat Jadid (a close supporter of Jadid and commander of the 70th Armoured Brigade).[67]

By the Fourth Regional Congress and Tenth National Congress in September and October 1968, Assad had extended his grip on the army, and Jadid still controlled the party.[67] At both congresses, Assad was outvoted on most issues, and his arguments were firmly rejected.[67] While he failed in most of his attempts, he had enough support to remove two socialist theoreticians (Prime Minister Yusuf Zu'ayyin and Minister of Foreign Affairs Brahim Makhous) from the Regional Command.[67] However, the military's involvement in party politics was unpopular with the rank and file; as the gulf between Assad and Jadid widened, the civilian and military party bodies were forbidden to contact each other.[68] Despite this, Assad was winning the race to accumulate power.[68] As Munif al-Razzaz (ousted in the 1966 Syrian coup d'état) noted, "Jadid's fatal mistake was to attempt to govern the army through the party".[68]

Assad (center) and Nureddin al-Atassi (left) meeting with Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, 1969

While Assad had taken control of the armed forces through his position as Minister of Defense, Jadid still controlled the security and intelligence sectors through Abd al-Karim al-Jundi (head of the National Security Bureau).[68] Jundi—a paranoid, cruel man—was feared throughout Syria.[68] In February 1969, the Assad-Jadid conflict erupted in violent clashes through their respective proteges: Rifaat al-Assad (Assad's brother and a high-ranking military commander) and Jundi.[69] The reason for the violence was Rifaat al-Assad's suspicion that Jundi was planning an attempt on Assad's life.[69] The suspected assassin was interrogated and confessed under torture.[69] Acting on this information, Rifaat al-Assad argued that unless Jundi was removed from his post he and his brother were in danger.[69]

From 25 to 28 February 1969, the Assad brothers initiated "something just short of a coup".[69] Under Assad's authority, tanks were moved into Damascus and the staffs of al-Ba'ath and al-Thawra (two party newspapers) and radio stations in Damascus and Aleppo were replaced with Assad loyalists.[69] Latakia and Tartus, two Alawite-dominated cities, saw "fierce scuffles" ending with the overthrow of Jadid's supporters from local posts.[69] Shortly afterwards, a wave of arrests of Jundi loyalists began.[69] On 2 March, after a telephone argument with head of military intelligence Ali Dhadha, Jundi committed suicide.[69] When Zu'ayyin heard the news he wept, saying "we are all orphaned now" (referring to his and Jadid's loss of their protector).[70] Despite his rivalry with Jundi, Assad is said to have also wept when he heard the news.[69]

Assad was now in control, but he hesitated to push his advantage.[69] Jadid continued to rule Syria, and the Regional Command was unchanged.[70] However, Assad influenced Jadid to moderate his policies.[70] Class struggle was muted, criticism of reactionary tendencies of other Arab states ceased, some political prisoners were freed, a coalition government was formed (with the Ba'ath Party in control) and the Eastern Front—espoused by Assad—was formed with Iraq and Jordan.[71] Jadid's isolationist policies were curtailed, and Syria reestablished diplomatic relations with many of its foes.[71] Around this time, Gamal Abdel Nasser's Egypt, Houari Boumediene's Algeria and Ba'athist Iraq began sending emissaries to reconcile Assad and Jadid.[71]

1970 coup d'état

Assad began planning to seize power shortly after the failed Syrian military intervention in the Jordanian Black September crisis, a power struggle between the PLO and the Hashemite monarchy.[72] While Assad had been in de facto command of Syrian politics since 1969, Jadid and his supporters still held the trappings of power.[72] After attending Nasser's funeral, Assad returned to Syria for the Emergency National Congress (held on 30 October).[72] At the congress Assad was condemned by Jadid and his supporters, the majority of the party's delegates.[72] However, before attending the congress Assad ordered his loyal troops to surround the building housing the meeting.[72] Criticism of Assad's political position continued in a defeatist tone, with the majority of delegates believing that they had lost the battle.[72] Assad and Tlass were stripped of their government posts at the congress; these acts had little practical significance.[72]

When the National Congress ended on 12 November 1970, Assad ordered loyalists to arrest leading members of Jadid's government.[73] Although many mid-level officials were offered posts in Syrian embassies abroad, Jadid refused: "If I ever take power, you will be dragged through the streets until you die."[73] Assad imprisoned him in Mezze prison until his death.[73] The coup was calm and bloodless; the only evidence of change to the outside world was the disappearance of newspapers, radio and television stations.[73] A Temporary Regional Command was soon established, and on 16 November the new government published its first decree.[73]

Presidency: 1970–2000

Domestic events and policies

Consolidating power

Assad in November 1970, shortly after seizing power

According to Patrick Seale, Assad's rule "began with an immediate and considerable advantage: the government he displaced was so detested that any alternative came as a relief".[74] He first tried to establish national unity, which he felt had been lost under the leadership of Aflaq and Jadid.[75] Assad differed from his predecessor at the outset, visiting local villages and hearing citizen complaints.[75] The Syrian people felt that Assad's rise to power would lead to change;[76] one of his first acts as ruler was to visit Sultan Pasha al-Atrash, father of the Aflaqite Ba'athist Mansur al-Atrash, to honor his efforts during the Great Arab Revolution.[75] He made overtures to the Writers' Union, rehabilitating those who had been forced underground, jailed or sent into exile for representing what radical Ba'athists called the reactionary classes:[75] "I am determined that you shall no longer feel strangers in your own country."[75] Although Assad did not democratize the country, he eased the government's repressive policies.[77]

He cut prices for basic foodstuffs 15 percent, which won him support from ordinary citizens.[77] Jadid's security services were purged, some military criminal investigative powers were transferred to the police, and the confiscation of goods under Jadid was reversed.[77] Restrictions on travel to and trade with Lebanon were eased, and Assad encouraged growth in the private sector.[77] While Assad supported most of Jadid's policies, he proved more pragmatic after he came to power.[77]

Most of Jadid's supporters faced a choice: continue working for the Ba'ath government under Assad, or face repression.[77] Assad made it clear from the beginning "that there would be no second chances".[77] However, later in 1970 he recruited support from the Ba'athist old guard who had supported Aflaq's leadership during the 1963–1966 power struggle.[77] An estimated 2,000 former Ba'athists rejoined the party after hearing Assad's appeal, among them party ideologist Georges Saddiqni and Shakir al-Fahham, a secretary of the founding, 1st National Congress of the Ba'ath Party in 1947.[77] Assad ensured that they would not defect to the pro-Aflaqite Ba'ath Party in Iraq with the Treason Trials in 1971, in which he prosecuted Aflaq, Amin al-Hafiz and nearly 100 followers (most in absentia).[78] The few who were convicted were not imprisoned long, and the trials were primarily symbolic.[79]

At the 11th National Congress Assad assured party members that his leadership was a radical change from that of Jadid, and he would implement a "corrective movement" to return Syria to the true "nationalist socialist line".[80] Unlike Jadid, Assad emphasised "the advancement of which all resources and manpower [would be] mobilised [was to be] the liberation of the occupied territories".[80] This would mark a major break with his predecessors and would, according to Raymond Hinnebusch, dictate "major alterations in the course of the Ba'thist state".[80]

Institutionalization

Assad's first inauguration as President in the People's Council, March 1971. L–R: Assad, Abdullah al-Ahmar, Prime Minister Abdul Rahman Khleifawi, Assistant Regional Secretary Mohamad Jaber Bajbouj, Foreign Minister Abdul Halim Khaddam and People's Council Speaker Fihmi al-Yusufi. In the third civilian row are Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass (MP in the 1971 Parliament) and Air Force Commander Naji Jamil. Behind Tlass is Rifaat al-Assad, Assad's younger brother. On the far right in the fourth row is future vice president Zuhair Masharqa, and behind Abdullah al-Ahmar is Deputy Prime Minister Mohammad Haidar.

Assad turned the presidency, which had been known simply as "head of state" under Jadid, into a position of power during his rule.[81] In many ways, the presidential authority replaced the Ba'ath Party's failed experiment with organised, military Leninism;[81] Syria became a hybrid of Leninism and Gaullist constitutionalism.[81] According to Raymond Hinnebusch, "as the president became the main source of initiative in the government, his personality, values, strengths and weaknesses became decisive for its direction and stability. Arguably Assad's leadership gave the government an enhanced combination of consistency and flexibility which it hitherto lacked."[81]

Assad institutionalised a system where he had the final say, which weakened the powers of the collegial institutions of the state and party.[82] As fidelity to the leader replaced ideological conviction later in his presidency, corruption became widespread.[82] The state-sponsored cult of personality became pervasive; as Assad's authority strengthened at his colleagues' expense, he became the sole symbol of the government.[83][82] Because Assad wanted to become an Arab leader, he considered himself a successor to Nasser since he rose to power in November 1970 (a few weeks after Nasser's death).[84] He modeled his presidential system on Nasser's, hailed Nasser for his pan-Arabic leadership and publicly displayed photographs of Nasser with posters of himself.[83] Pictures of Assad—often engaged in heroic activities—were ubiquitous in public places.[84] He named a number of locations and institutions after himself and family members.[84] In schools, children were taught songs praising Assad.[84] Teachers began each lesson with the song "Our Eternal Leader, Hafez al-Assad",[84] and he was sometimes portrayed with seemingly divine attributes.[84] Sculptures and portraits depicted him with the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, and after his mother's death the government produced portraits of her with a halo.[84] Syrian officials were compelled to call Assad "the sanctified one" ("al-Muqaddas").[84] This strategy was also pursued by his son, Bashar al-Assad.[85]

While Assad did not rule alone, he increasingly had the last word;[86] those with whom he worked eventually became lieutenants, rather than colleagues.[86] None of the political elite would question a decision of his, and those who did were dismissed.[86] General Naji Jamil is an example, being dismissed after he disagreed with Assad's handling of the Islamic uprising.[86] The two highest decision-making bodies were the Regional Command and the National Command, both part of the Ba'ath Party.[87] Joint sessions of these bodies resembled politburos in socialist states which espoused communism.[87] Assad headed the National Command and the Regional Command as Secretary General and Regional Secretary, respectively.[87] The Regional Command was the highest decision-making body in Syria, appointing the president and (through him) the cabinet.[87] As presidential authority strengthened, the power of the Regional Command and its members evaporated.[88] The Regional and National Commands were nominally responsible to the Regional Congress and the National Congress—with the National Congress the de jure superior body—but the Regional Congress had de facto authority.[89] The National Congress, which included delegates from Ba'athist Regional Branches in other countries, has been compared to the Comintern.[90] It functioned as a session of the Regional Congress focusing on Syria's foreign policy and party ideology.[90] The Regional Congress had limited accountability until the 1985 Eighth Regional Congress, the last under Assad.[90] In 1985, responsibility for leadership accountability was transferred from the Regional Congress to the weaker National Progressive Front.[88]

Sectarianism

Assad with Sunni members of the political elite: (L–R) Ahmad al-Khatib, Assad, Abdullah al-Ahmar and Mustafa Tlass

When Assad came to power, he increased Alawite dominance of the security and intelligence sectors to a near-monopoly.[82] The coercive framework was under his control, weakening the state and party. According to Hinnebusch, the Alawite officers around Assad "were pivotal because as personal kinsmen or clients of the president, they combined privileged access to him with positions in the party and control of the levers of coercion. They were, therefore, in an unrivalled position to act as political brokers and, especially in times of crisis, were uniquely placed to shape outcomes".[82] The leading figures in the Alawite-dominated security system had family connections; Rifaat al-Assad controlled the Struggle Companies, and Assad's son-in-law Adnan Makhluf was his second-in-command as Commander of the Presidential Guard.[82] Other prominent figures were Ali Haydar (special-forces head), Ibrahim al-Ali (Popular Army head), Muhammad al-Khuli (head of Assad's intelligence-coordination committee) and Military Intelligence head Ali Duba.[91] Assad controlled the military through Alawites such as Generals Shafiq Fayyad (commander of the 3rd Division), Ibrahim Safi (commander of the 1st Division) and Adnan Badr Hasan (commander of the 9th Division).[92] During the 1990s, Assad further strengthened Alawite dominance by replacing Sunni General Hikmat al-Shihabi with General Ali Aslan as chief of staff.[92] The Alawites, with their high status, appointed and promoted based on kinship and favor rather than professional respect.[92] Therefore, an Alawite elite emerged from these policies.[92] Assad's elite was non-sectarian;[92] prominent Sunni figures at the beginning of his rule were Abdul Halim Khaddam, Shihabi, Naji Jamil, Abdullah al-Ahmar and Mustafa Tlass.[92]

However, none of these people had a distinct power base from that of Assad.[93] Although Sunnis held the positions of Air Force Commander from 1971 to 1994 (Jamil, Subhi Haddad and Ali Malahafji), General Intelligence head from 1970 to 2000 (Adnan Dabbagh, Ali al-Madani, Nazih Zuhayr, Fuad al-Absi and Bashir an-Najjar), Chief of Staff of the Syrian Army from 1974 to 1998 (Shihabi) and defense minister from 1972 until after Assad's death (Tlass), none had power separate from Assad or the Alawite-dominated security system.[93] When Jamil headed the Air Force, he could not issue orders without the knowledge of Khuli (the Alawite head of Air Force Intelligence).[93] After the failed Islamic uprising, Assad's reliance on his relatives intensified;[93] before that, his Sunni colleagues had some autonomy.[93] A defector from Assad's government said, "Tlass is in the army but at the same time seems as if he is not of the army; he neither binds nor loosens and has no role other than that of the tail in the beast."[94] Another example was Shihabi, who occasionally represented Assad.[94] However, he had no control in the Syrian military; Ali Aslan, First Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations during most of his tenure, was responsible for troop maneuvers.[94] Although the Sunnis were in the forefront, the Alawites had the power.[94]

Islamist uprising

Background

Assad's pragmatic policies indirectly led to the establishment of a "new class",[95] and he accepted this while it furthered his aims against Israel.[95] When Assad began pursuing a policy of economic liberalization, the state bureaucracy began using their positions for personal gain.[95] The state gave implementation rights to "much of its development program to foreign firms and contractors, fueling a growing linkage between the state and private capital".[96] What ensued was a spike in corruption, which led the political class to be "thoroughly embourgeoised".[96] The channeling of external money through the state to private enterprises "created growing opportunities for state elites' self-enrichment through corrupt manipulation of state-market interchanges. Besides outright embezzlement, webs of shared interests in commissions and kickbacks grew up between high officials, politicians, and business interests".[96] The Alawite military-security establishment got the greatest share of the money;[97] the Ba'ath Party and its leaders ruled a new class, defending their interests instead of those of peasants and workers (whom they were supposed to represent).[97] This, coupled with growing Sunni disillusionment with what Hinnebusch calls "the regime's mixture of statism, rural and sectarian favouritism, corruption and new inequalities", fueled the growth of the Islamic movement.[98] Because of this, the Muslim Brotherhood of Syria became the vanguard of anti-Ba'athist forces.[99]

The Brotherhood had historically been a vehicle for moderate Islam during its introduction to the Syrian political scene during the 1960s under the leadership of Mustafa al-Siba'i.[99] After Siba'i's imprisonment, under Isam al-Attar's leadership the Brotherhood developed into the ideological antithesis of Ba'athist rule.[99] However, the Ba'ath Party's organizational superiority worked in its favor;[99] with Attar's enforced exile, the Muslim Brotherhood was in disarray.[99] It was not until the 1970s that the Muslim Brotherhood established a clear, central collective authority for its organization under Adnan Saad ad-Din, Sa'id Hawwa, Ali Sadr al-Din al-Bayanuni and Husni Abu.[99] Because of their organizational capabilities, the Muslim Brotherhood grew tenfold from 1975 to 1978 (from 500–700 in Aleppo); nationwide, by 1978 it had 30,000 followers.[99]

Events

The Islamic uprising began in the mid-to-late 1970s, with attacks on prominent members of the Ba'ath Alawite elite.[100] As the conflict worsened, a debate in the party between hard-liners (represented by Rifaat al-Assad) and Ba'ath liberals (represented by Mahmoud al-Ayyubi) began.[100] The Seventh Regional Congress, in 1980, was held in an atmosphere of crisis.[101] The party leadership—with the exception of Assad and his proteges—were criticised severely by party delegates, who called for an anti-corruption campaign, a new, clean government, curtailing the powers of the military-security apparatus and political liberalization.[101] With Assad's consent, a new government (headed by the presumably clean Abdul Rauf al-Kasm) was established with new, young technocrats.[101] The new government failed to assuage critics, and the Sunni middle class and the radical left (believing that Ba'athist rule could be overthrown with an uprising) began collaborating with the Islamists.[101]

Section of Hama after attack by government forces

Believing they had the upper hand in the conflict, beginning in 1980 the Islamists began a series of campaigns against government installations in Aleppo;[101] the attacks became urban guerilla warfare.[101] The government began to lose control in the city and, inspired by events, similar disturbances spread to Hama, Homs, Idlib, Latakia, Deir ez-Zor, Maaret-en-Namen and Jisr esh-Shagour.[101] Those affected by Ba'athist repression began to rally behind the insurgents; Ba'ath Party co-founder Bitar supported the uprising, rallying the old, anti-military Ba'athists.[101] The increasing threat to the government's survival strengthened the hard-liners, who favored repression over concessions.[101] Security forces began to purge all state, party and social institutions in Syria, and were sent to the northern provinces to quell the uprising.[102] When this failed, the hard-liners began accusing the United States of fomenting the uprising and called for the reinstatement of "revolutionary vigilance".[102] The hard-liners won the debate after a failed attempt on Assad's life in June 1980,[102] and began responding to the uprising with state terrorism later that year.[102] Under Rifaat al-Assad Islamic prisoners at the Tadmur prison were massacred, membership in the Muslim Brotherhood became a capital offence and the government sent a death squad to kill Bitar and Attar's former wife.[102] The military court began condemning captured militants, which "sometimes degenerated into indiscriminate killings".[102] Little care was taken to distinguish Muslim Brotherhood hard-liners from their passive supporters,[102] and violence was met with violence.[102]

The final showdown, the Hama massacre, took place in February 1982[102] when the government crushed the uprising.[103] Helicopter gunships, bulldozers and artillery bombardment razed the city, killing thousands of people.[103] The Ba'ath government withstood the uprising not because of popular support, but because the opposition was disorganised and had little urban support.[103] Throughout the uprising, the Sunni middle class continued to support the Ba'ath Party because of its dislike of political Islam.[103] After the uprising the government resumed its version of militaristic Leninism, reverting the liberalization introduced when Assad came to power.[104] The Ba'ath Party was weakened by the uprising; democratic elections for delegates to the Regional and National Congresses were halted, and open discussion within the party ended.[104] The uprising made Syria more totalitarian than ever, and strengthened Assad's position as undisputed leader of Syria.[104]

1983–1984 succession crisis

Assad (r) with his brother, Rifaat al-Assad, 1980s

In November 1983 Assad, a diabetic, had a major heart attack complicated by phlebitis;[105] this triggered a succession crisis.[106] On 13 November, after visiting his brother in the hospital,[107] Rifaat al-Assad reportedly announced his candidacy for president; he did not believe Assad would be able to continue ruling the country.[106] When he did not receive support from Assad's inner circle, he made, in the words of historian Hanna Batatu, "abominably lavish" promises to win them over.[106]

Until his 1985 ouster, Rifaat al-Assad was considered the face of corruption by the Syrian people.[107] Although highly paid as Commander of Defense Companies, he accumulated unexplained wealth.[107] According to Hanna Batatu, "there is no way that he could have permissibly accumulated the vast sums needed for the investments he made in real estate in Syria, Europe and the United States".[107]

Although it is unclear if any top officials supported Rifaat al-Assad, most did not.[108] He lacked his brother's stature and charisma, and was vulnerable to charges of corruption.[108] His 50,000-strong Defense Companies were viewed with suspicion by the upper leadership and throughout society;[108] they were considered corrupt, poorly disciplined and indifferent to human suffering.[108] Rifaat al-Assad also lacked military support;[108] officers and soldiers resented the Defense Companies' monopoly of Damascus' security, their separate intelligence services and prisons and their higher pay.[109] He did not abandon the hope of succeeding his brother, opting to take control of the country through his post as Commander of Defense Companies.[110] In what became known as the "poster war", personnel from the Defense Companies replaced posters of Assad in Damascus with those of Rifaat al-Assad.[110] The security service, still loyal to Assad, responded by replacing Rifaat al-Assad's posters with Assad's.[110] The poster war lasted for a week, until Assad's health improved.[110]

Shortly after the poster war, all Rifaat al-Assad's proteges were removed from positions of power.[110] This decree nearly sparked a clash between the Defense Companies and the Republican Guard on 27 February 1984, but conflict was avoided by Rifaat al-Assad's appointment as one of three Vice Presidents on 11 March.[110] He acquired this post by surrendering his position as Commander of Defense Companies to an Assad supporter.[110] Rifaat al-Assad was succeeded as Defense Companies head by his son-in-law.[110] During the night of 30 March, he ordered Defense Company loyalists to seal Damascus off and advance to the city.[110] The Republican Guard was put on alert in Damascus, and 3rd Armored Division commander Shafiq Fayyad ordered troops outside Damascus to encircle the Defense Companies blocking the roads into the city.[111] Rifaat al-Assad's plan might have succeeded if Special Forces commander Ali Haydar supported him, but Haydar sided with the president.[111] Assad punished Rifaat al-Assad with exile, allowing him to return in later years without a political role.[111] The Defense Companies were reduced by 30,000–35,000 people,[112] and their role was assumed by the Republican Guard.[112] Makhluf, the Republican Guard commander, was promoted to major general, and Bassel al-Assad (Assad's son, an army major) became influential in the guard.[112]

Autocracy, succession and death

Assad and his wife, Anisa Makhlouf; back row, left to right: Maher, Bashar, Bassel, Majid and Bushra al-Assad

Mausoleum of Hafez al-Assad in Qardaha

Assad's first choice of successor was his brother Rifaat al-Assad, an idea he broached as early as 1980,[113] and his brother's coup attempt weakened the institutionalised power structure on which he based his rule.[114] Instead of changing his policy, Assad tried to protect his power by honing his governmental model.[114] He gave a larger role to Bassel al-Assad, who was rumored to be his father's planned successor;[114] this kindled jealousy within the government.[114] At a 1994 military meeting, Chief of Staff Shihabi said that since Assad wanted to normalize relations with Israel, the Syrian military had to withdraw its troops from the Golan Heights. Haydar replied angrily, "We have become nonentities. We were not even consulted."[114] When he heard about Haydar's outburst, Assad replaced Haydar as Commander of Special Forces with the Alawite Major General Ali Habib.[115] Haydar also reportedly opposed dynastic succession, keeping his views secret until after Bassel's death in 1994 (when Assad chose Bashar al-Assad to succeed him);[116] he then openly criticised Assad's succession plans.[116]

Bassel al-Assad became a security officer at the Presidential Palace in 1986, and a year later he was appointed Commander of the Defense Companies.[117] About this time, rumors spread that Assad planned to make Bassel his successor.[117] Bassel al-Assad continued his climb to the top; at the time of the 1991 presidential referendum, citizens were ordered to sing songs praising him.[117] Vehicles belonging to the military and the secret police began bearing images of Bassel,[117] and Assad began to be called the "Father of Bassel" in official media.[117] Bassel al-Assad went on his first foreign mission representing his country, traveling to Saudi Arabia to visit King Fahd.[117] Shortly before his death, he represented his absent father at an official event.[117] On 21 January 1994, Bassel al-Assad died in a car accident.[117] In his eulogy, Assad called his son's death a "national loss".[117] Bassel al-Assad, in death, played as great a role in his country's life as he did alive: his picture appeared on walls, cars, stores, dishes, clothing and watches.[118] The Syrian Regional Branch of the Ba'ath Party began indoctrinating youths with a Bassel al-Assad course.[118] Almost immediately after Bassel's death, Assad began to groom his 29-year-old son Bashar al-Assad for succession.[118]

Abdul Halim Khaddam, Syria's foreign minister from 1970 to 1984, opposed dynastic succession on the grounds that it was not socialist.[113] Khaddam has said that Assad never discussed his intentions about succession with members of the Regional Command.[113] By the 1990s, the Sunni faction of the leadership was aging; the Alawites, with Assad's help, had received new blood.[119] The Sunnis were at a disadvantage, since many were opposed to any kind of dynastic succession.[120]

—Abdul Halim Khaddam, on Assad's succession plans[113]

When he returned to Syria, Bashar al-Assad enrolled in the Homs Military Academy.[121] He was quickly promoted to Brigadier Commander, and served for a time in the Republican Guard.[122] He studied most military subjects, "including tank battalion commander, command and staff"[122] (the latter two of which were required for a senior command in the Syrian army).[122] Bashar al-Assad was promoted to lieutenant general in July 1997, and to colonel in January 1999.[123] Official sources ascribe Bashar's rapid promotion to his "overall excellence in the staff officers' course, and in the outstanding final project he submitted as part of the course for command and staff".[123] With Bashar's training, Assad appointed a new generation of Alawite security officers to secure his succession plans.[122] Shihabi's replacement by Aslan as Chief of Staff on 1 July 1998—Shihabi was considered a potential successor by the outside world—marked the end of the long security-apparatus overhaul.[122] Skepticism of Assad's dynastic-succession plan was widespread within and outside the government, with critics noting that Syria was not a monarchy.[122] By 1998 Bashar al-Assad had made inroads into the Ba'ath Party, taking over Khaddam's Lebanon portfolio (a post he had held since the 1970s).[124] By December 1998 Bashar al-Assad had replaced Rafiq al-Hariri, Prime Minister of Lebanon and one of Khaddam's proteges, with Selim Hoss.[125]

Several Assad proteges, who had served since 1970 or earlier, were dismissed from office between 1998 and 2000.[126] They were sacked not because of disloyalty to Assad, but because Assad thought they would not fully support Bashar al-Assad's succession.[126] "Retirees" included Muhammad al-Khuli, Nassir Khayr Bek and Ali Duba.[126] Among the new appointees (Bashar loyalists) were Bahjat Sulayman, Major General Halan Khalil and Major General Asaf Shawkat (Assad's son-in-law).[126]

By the late 1990s, Assad's health had deteriorated.[127] American diplomats said Assad had difficulty staying focused and seemed tired during their meetings;[128] he was seen as incapable of functioning for more than two hours a day.[128] His spokesperson ignored the speculation, and Assad's official routine in 1999 was basically unchanged from the previous decade.[128] Assad continued to conduct meetings, traveling abroad occasionally; he visited Moscow in July 1999.[128] Because of his increasing seclusion from state affairs, the government became accustomed to working without his involvement in day-to-day affairs.[128] On 10 June 2000, at the age of 69, Hafez al-Assad died of a heart attack while on the telephone with Lebanese prime minister Hoss.[129] 40 days of mourning was declared in Syria and 7 days in Lebanon thereafter.[130] His funeral was held three days later.[131] Assad is buried with his son, Bassel al-Assad, in a mausoleum in his hometown of Qardaha.[132]

Economy

Tabqa Dam (center), built in 1974

Assad called his domestic reforms a corrective movement, and it achieved some results. He tried to modernize Syria's agricultural and industrial sectors; one of his main achievements was the completion of the Tabqa Dam on the Euphrates River in 1974. One of the world's largest dams, its reservoir was called Lake Assad. The reservoir increased irrigation of arable land, provided electricity, and encouraged industrial and technical development in Syria. Many peasants and workers received increased income, social security, and better health and educational services. The urban middle class, which had been hurt by the Jadid government's policy, had new economic opportunities.[133]

By 1977 it was apparent that despite some success, Assad's political reforms had largely failed. This was partly due to Assad's foreign policy, failed policies, natural phenomena and corruption. Chronic socioeconomic difficulties remained, and new ones appeared. Inefficiency, mismanagement, and corruption in the government, public, and private sectors, illiteracy, poor education (particularly in rural areas), increasing emigration by professionals, inflation, a growing trade deficit, a high cost of living and shortages of consumer goods were among problems faced by the country. The financial burden of Syria's involvement in Lebanon since 1976 contributed to worsening economic problems, encouraging corruption and a black market. The emerging class of entrepreneurs and brokers became involved with senior military officers—including Assad's brother Rifaat—in smuggling from Lebanon, which affected government revenue and encouraged corruption among senior governmental officials.[134]

During the early 1980s, Syria's economy worsened; by mid-1984, the food crisis was severe, and the press was full of complaints. Assad's government sought a solution, arguing that food shortages could be avoided with careful economic planning. The food crisis continued through August, despite government measures. Syria lacked sugar, bread, flour, wood, iron and construction equipment; this resulted in soaring prices, long queues and rampant black marketeering. Smuggling goods from Lebanon became common. Assad's government tried to combat the smuggling, encountering difficulties due to the involvement of his brother Rifaat in the corruption. In July 1984, the government formed an effective anti-smuggling squad to control the Lebanon–Syria borders. The Defense Detachment commanded by Rifaat al-Assad played a leading role in the smuggling, importing $400,000 worth of goods a day. The anti-smuggling squad seized $3.8 million in goods during its first week.[135]

The Syrian economy grew five to seven percent during the early 1990s; exports increased, the balance of trade improved, inflation remained moderate (15–18 percent) and oil exports increased. In May 1991 Assad's government liberalised the Syrian economy, which stimulated domestic and foreign private investment. Most foreign investors were Arab states around the Persian Gulf, since Western countries still had political and economic issues with the country. The Gulf states invested in infrastructure and development projects; because of the Ba'ath Party's socialist ideology, Assad's government did not privatize state-owned companies.[136]

Syria fell into recession during the mid-1990s. Several years later, its economic growth was about 1.5 percent. This was insufficient, since population growth was between 3 and 3.5 percent. Another symptom of the crisis was statism in foreign trade. Syria's economic crisis coincided with recession in world markets. A 1998 drop in oil prices dealt a major blow to Syria's economy; when oil prices rose the following year, the Syrian economy partially recovered. In 1999, one of the worst droughts in a century caused a drop of 25–30 percent in crop yields compared with 1997 and 1998. Assad's government implemented emergency measures, including loans and compensation to farmers and the distribution of free fodder to save sheep and cattle. However, those steps were limited and had no measurable effect on the economy.[137]

Assad's government tried to decrease population growth, but this was only marginally successful. One sign of economic stagnation was Syria's lack of progress in talks with the EU on an agreement. The main cause of this failure was the country's difficulty in meeting EU demands to open the economy and introduce reforms. Marc Pierini, head of the EU delegation in Damascus, said that if the Syrian economy was not modernised it would not benefit from closer ties to the EU. Assad's government gave civil servants a 20-percent pay raise on the anniversary of the corrective movement that brought him to power. Although the foreign press criticised Syria's reluctance to liberalize its economy, Assad's government refused to modernize the bank system, permit private banks and open a stock exchange.[138]

Foreign policy

Yom Kippur War

Planning

Since the Arab defeat in the Six-Day War, Assad was convinced that the Israelis had won the war by subterfuge;[139] after gaining power, his top foreign-policy priority was to regain the Arab territory lost in the war.[139] Assad reaffirmed Syria's rejection of the 1967 UN Security Council Resolution 242 because he believed it stood for the "liquidation of the Palestine question".[139] He believed, and continued to believe until long into his rule, that the only way to get Israel to negotiate with the Arabs was through war.[139]

When Assad took power, Syria was isolated;[139] planning an attack on Israel, he sought allies and war material.[140] Ten weeks after gaining power, Assad visited the Soviet Union.[140] The Soviet leadership was wary of supplying the Syrian government, viewing Assad's rise to power with reserve and believing him to lean further West than Jadid did.[141] While he soon understood that the Soviet relationship with the Arabs would never be as deep as the United States' relationship with Israel, he needed its weapons.[141] Unlike his predecessors (who tried to win Soviet support with socialist policies), Assad was willing to give the Soviets a stable presence in the Middle East through Syria, access to Syrian naval bases (giving them a role in the peace process) and help in curtailing American influence in the region.[141] The Soviets responded by sending arms to Syria.[141] The new relationship bore fruit, and between February 1971 and October 1973 Assad met several times with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev.[142]

Assad believed that Syria would have no chance in a war against Israel without Egyptian participation.[143] He believed that if the United Arab Republic had not collapsed, the Arabs would already have liberated Palestine.[143] For a war against Israel, Syria needed to establish another front.[143] However, by this time Syria's relations with Egypt and Jordan were shaky at best.[143] Planning for war began in 1971 with an agreement between Assad and Anwar Sadat.[143] At the beginning, the renewed Egyptian–Syrian alliance was based upon the proposed Federation of Arab Republics (FAR), a federation initially encompassing Egypt, Libya, Sudan (which left soon after FAR's first summit) and Syria.[76] Assad and Sadat used the FAR summits to plan war strategy, and by 1971 they had appointed Egyptian General Muhammad Sadiq supreme commander of both armies.[144] From 1972 to 1973, the countries filled their arsenals and trained their armies.[144] In a secret meeting of the Egyptian–Syrian Military Council from 21 to 23 August 1973, the two chiefs of staff (Syrian Yusuf Shakkur and Egyptian Sad al-Shazly) signed a document declaring their intention to go to war against Israel.[145] During a meeting of Assad, Sadat and their respective defense ministers (Tlass and Hosni Mubarak) on 26–27 August, the two leaders decided to go to war together.[146]

Egypt went to war for a different reason than Syria did.[147] While Assad wanted to regain lost Arab territory, Sadat wished to strengthen Egypt's position in its peace policy toward Israel.[147] The Syrians were deceived by Sadat and the Egyptians, which would play a major role in the Arab defeat.[148] Egyptian Chief of Staff Shazly was convinced from the beginning that Egypt could not mount a successful full-scale offensive against Israel; therefore, he campaigned for a limited war.[148] Sadat knew that Assad would not participate in the war if he knew his real intentions.[148] Since the collapse of the UAR, the Egyptians were critical of the Ba'athist government; they saw it as an untrustworthy ally.[148]

The war

Assad and Mustafa Tlass on the Golan front

At 14:05 on 6 October 1973, Egyptian forces (attacking through the Sinai desert) and Syrian forces (attacking the Golan Heights) crossed the border into Israel and penetrated the Israeli defense lines.[149] The Syrian forces on the Golan Heights met with more intense fighting than their Egyptian counterparts, but by 8 October had broken through the Israeli defenses.[150] The early successes of the Syrian army were due to its officer corps (where officers were promoted because of merit and not politics) and its ability to handle advanced Soviet weaponry: tanks, artillery batteries, aircraft, man-portable missiles, the Sagger anti-tank weapon and the 2K12 Kub anti-aircraft system on mobile launchers.[150] With the help of these weapons, Egypt and Syria defeated Israel's armor and air supremacy.[150] Egypt and Syria announced the war to the world first, accusing Israel of starting it, mindful of the importance of avoiding appearing as the aggressor (Israel accused the Arab powers of starting the Six-Day War when they launched Operation Focus).[150] In any case, early Syrian successes helped rectify the loss of face they had suffered following the Six-Day War.

The main reason for the reversal of fortune was Egypt's operational pause from 7 to 14 October.[150] After capturing parts of the Sinai, the Egyptian campaign halted and the Syrians were left fighting the Israelis alone.[151] The Egyptian leaders, believing their war aims accomplished, dug in.[152] While their early successes in the war had surprised them, War Minister General Ahmad Ismail Ali advised caution.[152] In Syria, Assad and his generals waited for the Egyptians to move.[152] When the Israeli government learned of Egypt's modest war strategy, it ordered an "immediate continuous action" against the Syrian military.[152] According to Patrick Seale, "For three days, 7, 8, and 9 October, Syrian troops on the Golan faced the full fury of the Israeli air force as, from first light to nightfall, wave after wave of aircraft swooped down to bomb, strafe and napalm their tank concentration and their fuel and ammunition carriers right back to the Purple Line."[153] By 9 October, the Syrians were retreating behind the Purple Line (the Israeli–Syrian border since the Six-Day War).[154] By 13 October the war was lost, but (in contrast to the Six-Day War) the Syrians were not crushed; this earned Assad respect in Syria and abroad.[155]

On 14 October, Egypt began a limited offensive against Israel for political reasons.[156] Sadat needed Assad on his side for his peace policy with Israel to succeed,[156] and military action was a means to an end.[156] The renewed Egyptian military offensive was ill-conceived. A week later, due to Egyptian inactivity, the Israelis had organised and the Arabs had lost their most important advantage.[157] While the military offensive gave Assad hope, this was an illusion; the Arabs had already lost the war militarily.[158] Egypt's behavior during the war caused friction between Assad and Sadat.[158] Assad, still inexperienced in foreign policy, believed that the Egyptian–Syrian alliance was based on trust and failed to understand Egypt's duplicity.[158] Although it was not until after the war that Assad would learn that Sadat was in contact with American National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger almost daily during the war, the seeds of distrust had been sown.[159] Around this time, Sadat called for an American-led ceasefire agreement between Egypt, Syria and Israel; however, he was unaware that under Kissinger's tenure the United States had become a staunch supporter of Israel.[160]

Assad in a rage after Sadat visits Israel, 1977

On 16 October, Sadat—without telling Assad—called for a ceasefire in a speech to the People's Assembly, the Egyptian legislative body.[161] Assad was not only surprised, but could not comprehend why Sadat trusted "American goodwill for a satisfactory result".[161]Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin visited Cairo, urging Sadat to accept a ceasefire without the condition of Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories.[162] While Sadat was reluctant at first, Kosygin returned on 18 October with satellite images showing 300 Israeli tanks in Egyptian territory.[162] The blow to Sadat's morale was such that he sent a cable to Assad, obliquely saying that all hope was lost.[162] Assad, who was in a better position, was still optimistic.[163] Under Soviet influence Egypt called for a ceasefire on 22 October 1973, direct negotiations between the warring parties and the implementation of the UN Security Council Resolution 242.[163] The ceasefire resolution did not call for Israeli withdrawal from its occupied territories.[163] Assad was annoyed, since he had not been informed beforehand of Sadat's change in policy (which affected them both).[163] On 23 October the Syrian government accepted the ceasefire, spelling out its understanding of UN Resolution 338 (withdrawal of Israeli troops from the occupied territories and the safeguarding of Palestinian rights).[164]

Lebanese Civil War

—Assad, reviewing Syria's intervention in Lebanon[165]

Syria intervened in Lebanon in 1976 during the civil war which began in 1975.[166] With the establishment of an Egyptian–Israeli alliance, Syria was the only neighboring state which threatened Israel.[167] Syria initially tried to mediate the conflict; when that failed, Assad ordered the Palestine Liberation Army (PLA),[168] a regular force based in Syria with Syrian officers,[169] troops into Lebanon to restore order.[168] Around this time, the Israeli government opened its borders to Maronite refugees in Lebanon to strengthen its regional influence.[170] Clashes between the Syria-loyal PLA and militants occurred throughout the country.[170] Despite Syrian support and Khaddam's mediation, Rashid Karami (the Sunni Muslim Prime Minister of Lebanon) did not have enough support to appoint a cabinet.[170]

In early 1976 Assad was approached by Lebanese politicians for help in forcing the resignation of Suleiman Frangieh, the Christian President of Lebanon.[171] Although Assad was open to change, he resisted attempts by some Lebanese politicians to enlist him in Frangieh's ouster;[171] when General Abdul Aziz al-Ahdāb attempted to seize power, Syrian troops stopped him.[172] In the meantime, radical Lebanese leftists were gaining the upper hand in the military conflict.[172]Kamal Jumblatt, leader of the Lebanese National Movement (LNM), believed that his strong military position would compel Frangieh's resignation.[172] Assad did not wish a leftist victory in Lebanon which would strengthen the position of the Palestinians.[172] He did not want a rightist victory either, instead seeking a middle-ground solution which would safeguard Lebanon and the region.[172] When Jumblatt met with Assad on 27 March 1976, he tried to persuade him to let him "win" the war;[172] Assad replied that a ceasefire should be in effect to ensure the 1976 presidential elections.[172] Meanwhile, on Assad's orders Syria sent troops into Lebanon without international approval.[172]

While Yasser Arafat and the PLO had not officially taken a side in the conflict, several PLO members were fighting with the LNM.[172] Assad attempted to steer Arafat and the PLO away from Lebanon, threatening him with a cutoff of Syrian aid.[172] The two sides were unable to reach an agreement.[172] When Frangieh stepped down in 1976, Syria pressured Lebanese members of parliament to elect Elias Sarkis president.[173] One-third of the Lebanese members of parliament (primarily supporters of Raymond Edde) boycotted the election to protest American and Syrian interference.[173]

On 31 May 1976, Syria began a full-scale intervention in Lebanon to (according to the official Syrian account) end bombardment of the Maronite cities of Qubayat and Aandqat.[174] Before the intervention, Assad and the Syrian government were one of several interests in Lebanon; afterwards, they were the controlling factors in Lebanese politics.[174] On Assad's orders, the Syrian troop presence slowly increased to 30,000.[174] Syria received approval for the intervention from the United States and Israel to help them defeat Palestinian forces in Lebanon.[174] The Ba'athist group As-Sa'iqa and the PLA's Hittīn brigade fought Palestinians who sided with the LNM.[174]

Within a week of the Syrian intervention, Christian leaders issued a statement of support.[175] In a 1976 diplomatic cable released by WikiLeaks, a US diplomat stated "if I got nothing else from my meeting with Frangie, Chamoun and Gemayel, it is their clear, unequivocal and unmistakable belief that their principal hope for saving Christian necks is Syria. They sound like Assad is the latest incarnation of the Crusaders."[176]