Tritone substitution

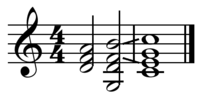

C7 is transpositionally equivalent to the F♯7, the leading tones resolve inversionally (E-B♭ resolves to F-A, A♯-E resolves to B-D♯)

The tritone substitution is one of the most common chord substitutions found in jazz and was the precursor to more complex substitution patterns like Coltrane changes. Tritone substitutions are sometimes used in improvisation—often to create tension during a solo. Though examples of the tritone substitution, known in the classical world as an augmented sixth chord, can be found extensively in classical music since the Renaissance period,[1] they were not heard until much later in jazz by musicians such as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker in the 1940s,[2] as well as Duke Ellington, Art Tatum, Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge and Benny Goodman.[3]

The tritone substitution can be performed by exchanging a dominant seven chord for another dominant seven chord which is a tritone away from it. For example, in the key of C major one can use D♭7 instead of G7. (D♭ is a tritone away from G).

Contents

1 Summary

2 Analysis

2.1 Jazz

2.2 Classical

2.3 In twelve-bar blues

2.4 In a ii–V–I progression

3 In other tuning systems

4 See also

5 References

6 Bibliography

Summary

In tonal music, a conventional perfect cadence consists of a dominant seventh chord followed by a tonic chord. For example, in the key of C major, the chord of G7 is followed by a chord of C. In order to execute a tritone substitution, common variant of this progression, one would replace the dominant seventh chord with a dominant chord that has its root a tritone away from the original:

Three kinds of perfect cadence

Franz Schubert’s String Quintet in C major concludes with a dramatic final cadence that uses the third of the above progressions. The conventional G7 chord is replaced in bars 3 and 4 of the following example with a D♭7 chord, with a diminished fifth (G♮ as the enharmonic equivalent of A![]() ); a chord otherwise known as a ‘French sixth’:

); a chord otherwise known as a ‘French sixth’:

Schubert, Quintet in C, final bars. Listen

Christopher Gibbs (2000, p. 105) says of this ending: “within the last movement of the quintet, darker forces continue to lurk: the piece ends with a manic coda building to a dissonant fortissimo chord with a D-flat trill in both cellos, and then a final tonic inflected by a D-flat appoggiatura… The effect is overwhelmingly powerful.”[4]

There are similarities here with the ambivalent ending of Richard Strauss’s tone poem Also Sprach Zarathustra. Here, according to Richard Taruskin, “Strauss contrived an ending that seemed to die away on an oscillation between tonics on B and C, with C … getting the last word. Had B been given the last word, or were the extreme registers reversed, the ploy would not have worked. It would have been obvious that the C (though placed many octaves lower than its rival, in a register the ear is used to associating with the fundamental bass) was, in functional terms, making a descent to the tonic B as part of a “French sixth” chord… Rather than an ending in two keys, we are dealing with a registrally distorted, interrupted, yet functionally viable cadence on B.”[5]

Analysis

Jazz

F♯7 may substitute for C7 because they both have E♮ and B♭/A♯ and pay due to voice leading considerations.

A tritone substitution is the substitution of one dominant seventh chord (possibly altered or extended) with another that is three whole steps (a tritone) from the original chord. In other words, tritone substitution involves replacing V7 with ♭II7[6] (which could also be called ♭V7/V, subV7,[6] or V7/♭V[6]). For example, D♭7 is the tritone substitution for G7.

In standard jazz harmony, tritone substitution works because the two chords share two pitches: namely, the third and seventh, albeit reversed.[7] In a G7 chord, the third is B and the seventh is F; whereas, in its tritone substitution, D♭7, the third is F and the seventh is C♭ (enharmonically B♮). Notice that the interval between the third and seventh of a dominant seventh chord is itself a tritone.

C7 followed quickly by the tritone it contains (E-B♭), its inversion (B♭-F♭), and then G♭7

Edward Sarath calls tritone substitutions a "non-diatonic practice that is indirectly related to applied chord functions... yield[ing] an alternative melodic pathway in the bass to the tonic triad."[6] Patricia Julien says it involves replacing "harmonic root movement of a fifth with stepwise root movements (e.g., G7–C becomes D♭7–C) so that although stepwise root movement is involved, the relationship between the chords is functional".[8]

The tritone substitute dominant often contains the original dominant pitch (the sharp fourth, also called sharp eleventh or flat fifth, relative to the original root) due to its importance melodically and tonally, and this is one of the ways in which substitute dominants may sound and function somewhat differently than conventional dominant chords.[9] (However, sharp elevenths also occur on non-substituted dominant chords in jazz.) The substitute dominant may be used as a pivot chord in modulation.[10] Since it is the dominant chord a tritone away, the substitute dominant may resolve down a fifth, to a tonic chord a tritone away from the previous tonic (for example, in F one may feature a ii–V on C, which with a substitute dominant resolves to G♭, a distant key from F). Resolution to the original tonic is also common.

Tritone substitutions are also closely related to the altered chord used commonly in jazz. Jerry Coker explains:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Tritone substitutions and altered dominants are nearly identical... Good improvisers will liberally sprinkle their solos with both devices. A simple comparison of the notes generally used with the given chord [notation] and the notes used in tri-tone substitution or altered dominants will reveal a rather stunning contrast, and could cause the unknowledgeable analyzer to suspect errors. ... the distinction between the two [tri-tone substitution and altered dominant] is usually a moot point.[11]

Tritone substitution and altered chord as, "nearly identical"[11]

The alt chord is a heavily altered dominant seventh chord, built on the alt scale, a scale where every scale degree except the root is flattened compared to the major scale. For example, C7alt is built from the scale C, D♭, E♭, F♭, G♭, A♭, B♭. Enharmonically, this is almost the same as the scale for G♭7, which is the tritone substitute of C7: G♭, A♭, B♭, C♭, D♭, E♭, F♭. The only difference is C, which is the sharp eleventh of the G♭7 chord. Thus, the alt chord is equivalent to the tritone substitution with a sharp–eleventh alteration.

The tritone substitution primarily implies a Lydian dominant scale. In the case of D♭7 to Cmaj7, the implied scale behind D♭7 would be D♭, E♭, F, G, A♭, B♭, C♭. Because of this, the extensions of 9, ♯11 and 13 are all available, while the ♯11 is where it shares with the altered scale.

Classical

Classical harmonic theory would notate the substitution as an augmented sixth chord on ♭II (the augmented sixth being enharmonic to the dominant/minor seventh). The augmented sixth chord can either be the Italian sixth It+6, which is enharmonically equivalent to a dominant seventh chord without the fifth; the German sixth Gr+6, which is enharmonically equivalent to a dominant seventh chord with the fifth; or the French sixth Fr+6, which is enharmonically equivalent to the Lydian dominant without the fifth but with a sharp eleven, all of which serve in a classical context as a substitute for the secondary dominant of V.[12][13]

Below is the original dominant-tonic progression, the same progression with the tritone substitution, and the same progression with the substitution notated as an Italian augmented sixth chord:

Original, tritone substitution, and augmented sixth chord

In twelve-bar blues

One of the most common usages of the tritone substitution is in the 12-bar blues. Shown below is one of the simpler forms of twelve-bar blues.

I

C7

IV

F7

I

C7

I

C7

IV

F7

IV

F7

I

C7

I

C7

V

G7

IV

F7

I

C7

I

C7

Next, here is the same 12 bars, except incorporating a tritone substitution in bar 4; that is, with G♭7 substituted for C7.

I

C7

IV

F7

I

C7

♭V

G♭7

IV

F7

IV

F7

I

C7

I

C7

V

G7

IV

F7

I

C7

I

C7

In a ii–V–I progression

The second common usage of the tritone substitution is in ii–V–I progression, which is extremely common in jazz harmony. This substitution is particularly suitable for jazz because it produces chromatic root movement. For example, in the progression Dm7–G7–CM7, substituting D♭7 for G7 produces the downward movement of D–D♭–C in the roots of the chords, typically played by the bass. This also reinforces the downward movement of the thirds and sevenths of the chords in the progression (in this case, F/C to F/C♭ to E/B).

.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{display:flex;flex-direction:column}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{display:flex;flex-direction:row;clear:left;flex-wrap:wrap;width:100%;box-sizing:border-box}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{margin:1px;float:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .theader{clear:both;font-weight:bold;text-align:center;align-self:center;background-color:transparent;width:100%}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{text-align:left;background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-left{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-right{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-center{text-align:center}@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;max-width:none!important;align-items:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{justify-content:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{text-align:center}}

In other tuning systems

The fact that a chord and its tritone substitution share the third and seventh in common is related to the fact that in 12 equal temperament, the 7:5 and 10:7 ratios are represented by the same interval, which is exactly half of an octave (600 cents) and is its own inversion. This is also the case in 22 equal temperament and tritone substitution works similarly there. However, in 31 equal temperament and other systems that distinguish between 7:5 and 10:7, tritone substitution becomes more complex. The harmonic seventh chord (approximating 4:5:6:7) contains a small tritone, so its substitution must contain a large tritone and therefore will be a different (and more dissonant) chord type.[15]

See also

- Bird blues

References

^ Kennedy, Andrews (1950). The Oxford Harmony. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 45–46..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Everett, Walter (Autumn, 2004). "A Royal Scam: The Abstruse and Ironic Bop-Rock Harmony of Steely Dan", Music Theory Spectrum, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 201-235

^ Owens, Thomas (1996). Bebop. Oxford University Press. p. 5.

^ Gibbs, C.H. (2000) The Life of Schubert. Cambridge University Press.

^ Taruskin, Richard (2005, p.53). The Oxford History of Western Music, Vol. 4: Music in the Early Twentieth Century. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

^ abcd Sarath, Edward (2009). Music Theory Through Improvisation: A New Approach to Musicianship Training, p.177.

ISBN 0-415-80453-1.

^ Freeman, Daniel E. (2009). The Art of Solo Bass, p.17.

ISBN 0-7866-0653-3.

^ Julien, Patricia (2001). Jazz Education Journal, Volume 34, p.ix–xi.

^ Ligon, Bert (2001). Jazz Theory Resources, p.128.

ISBN 0-634-03861-3.

^ Bahha and Rollins (2005). Jazzology, p.103.

ISBN 0-634-08678-2.

^ ab Coker, Jerry (1997). Elements of the Jazz Language for the Developing Improvisor, p.81.

ISBN 1-57623-875-X.

^ Satyendra, Ramon. "Analyzing the Unity within Contrast: Chick Corea's Starlight", p.55. Cited in Stein.

^ Stein, Deborah (2005). Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

ISBN 0-19-517010-5.

^ Scott DeVeaux (Autumn, 1999). "'Nice Work if You Can Get It': Thelonious Monk and Popular Song", p.180, Black Music Research Journal, Vol. 19, No. 2, New Perspectives on Thelonious Monk.

^ "Lesser Septimal Tritone".

Bibliography

- DeVeaux, Scott (1997). The birth of bebop: A social and musical history, p. 104-106. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- R., Ken (2012). DOG EAR Tritone Substitution for Jazz Guitar, Amazon Digital Services, Inc., ASIN: B008FRWNIW