Leninism

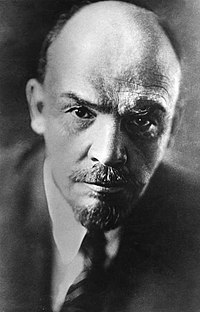

Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Bolsheviks

Leninism is the political theory for the organisation of a revolutionary vanguard party and the achievement of a dictatorship of the proletariat as political prelude to the establishment of socialism.[1] Developed by and named for the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, Leninism comprises socialist political and economic theories, developed from Marxism and Lenin's interpretations of Marxist theories, for practical application to the socio-political conditions of the Russian Empire of the early 20th century.

Functionally, the Leninist vanguard party was to provide the working class with the political consciousness (education and organisation) and revolutionary leadership necessary to depose capitalism in Imperial Russia.[1] After the October Revolution of 1917, Leninism became the dominant hegemonic force within the Russian revolutionary current, and in establishing further Bolshevik supremacy, the Bolsheviks had defeated the socialist opposition such as the Mensheviks and factions of the Socialist Revolutionary Party and also suppressed soviet democracy.[2] The Russian Civil War (1917–1922) thus included left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks (1918–1924) that were suppressed in the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (RSFSR) before incorporation to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1922.

Leninism was composed for revolutionary praxis and originally was neither a rigorously proper philosophy nor a discrete political theory. After the Russian Revolution and in History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics (1923), György Lukács developed and organised Lenin's pragmatic revolutionary practices and ideology into the formal philosophy of vanguard-party revolution (Leninism). As a political-science term, "Leninism" entered common usage in 1922 after infirmity ended Lenin's participation in governing the Russian Communist Party. At the Fifth Congress of the Communist International in July 1924, Grigory Zinoviev popularized the term "Leninism" to denote "vanguard-party revolution". From 1917 to 1922, Leninism was the Russian application of Marxist economics and political philosophy, effected and realised by the Bolsheviks, the vanguard party who led the fight for the political independence of the working class. In the 1925–1929 period, Joseph Stalin established his interpretation of Leninism as the official and only legitimate form of Marxism in Russia by amalgamating the political philosophies as Marxism–Leninism, which then became the state ideology of the Soviet Union.

Contents

1 Historical background

1.1 Imperialism

2 Leninist praxis

2.1 The vanguard party

2.2 Dictatorship of the proletariat

2.3 Economics

2.4 National self-determination

2.5 Socialist culture

3 Leninism after 1924

4 Philosophic successors

5 Criticism

6 See also

7 References

8 Further reading

9 External links

Historical background

Hungarian philosopher György Lukács (c. 1952) codified the theory and practice of Leninism in History and Class Consciousness (1923)

In the 19th century, The Communist Manifesto (1848), by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, called for the international political unification of the European working classes in order to achieve a communist revolution and proposed that because the socio-economic organization of communism was of a higher form than that of capitalism, a workers' revolution would first occur in the economically advanced, industrialized countries. Marxist social democracy was strongest in Germany throughout the 19th century and the Social Democratic Party of Germany inspired Lenin and other Russian Marxists.[3]

In the early 20th century, the socio-economic backwardness of Imperial Russia (1721–1917)—uneven and combined economic development—facilitated rapid and intensive industrialization, which produced a united, working-class proletariat in a predominantly rural, agrarian, peasant society. Moreover, because the industrialization was financed mostly with foreign capital, Imperial Russia did not possess a revolutionary bourgeoisie with political and economic influence upon the workers and the peasants (as occurred in the French Revolution, 1789). Although Russia's political economy principally was agrarian and semi-feudal, the task of democratic revolution therefore fell to the urban, industrial working class as the only social class capable of effecting land reform and democratization, in view that the Russian propertied classes would attempt to suppress any revolution, in town and country.

In April 1917, Lenin published the April Theses, the political strategy of the October Revolution (7–8 November 1917), which proposed that the Russian revolution was not an isolated national event, but a fundamentally international event—the first world socialist revolution. Thus Lenin's practical application of Marxism and working-class urban revolution to the social, political and economic conditions of the agrarian peasant society that was Tsarist Russia sparked the "revolutionary nationalism of the poor" to depose the absolute monarchy of the three-hundred-year Romanov dynasty (1613–1917).[4]

Imperialism

In the course of developing the Russian application of Marxism, the pamphlet Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916) presented Lenin's analysis of an economic development predicted by Karl Marx, namely that capitalism would become a global financial system, wherein advanced industrial countries export financial capital to their colonial countries, to finance the exploitation of their natural resources and the labour of the native populations. Such superexploitation of the poor (undeveloped) countries allows the wealthy (developed) countries to maintain some homeland workers politically content with a slightly higher standard of living and so ensure peaceful labour–capital relations in the capitalist homeland (see labour aristocracy and globalization). Hence, a proletarian revolution of workers and peasants could not occur in the developed capitalist countries while the imperialist global-finance system remained intact; thus an underdeveloped country would feature the first proletarian revolution; and in the early 20th century, Imperial Russia was the politically weakest country in the capitalist global-finance system.[5]

In the United States of Europe Slogan (1915), Lenin said: .mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Workers of the world, unite!—Uneven economic and political development is an absolute law of capitalism. Hence the victory of socialism is possible, first in several, or even in one capitalist country taken separately. The victorious proletariat of that country, having expropriated the capitalists and organised its own socialist production, would stand up against the rest of the world, the capitalist world.

— Collected Works, vol. 18, p. 232[6]

In Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder (1920), Lenin said:

The more powerful enemy can be vanquished only by exerting the utmost effort, and by the most thorough, careful, attentive, skillful and obligatory use of any, even the smallest, rift between the enemies, any conflict of interests among the bourgeoisie of the various countries and among the various groups or types of bourgeoisie within the various countries, and also by taking advantage of any, even the smallest, opportunity of winning a mass ally, even though this ally is temporary, vacillating, unstable, unreliable and conditional. Those who do not understand this reveal a failure to understand even the smallest grain of Marxism, of modern scientific socialism in general. Those who have not proved in practice, over a fairly considerable period of time and in fairly varied political situations, their ability to apply this truth in practice have not yet learned to help the revolutionary class in its struggle to emancipate all toiling humanity from the exploiters. And this applies equally to the period before and after the proletariat has won political power.

— Collected Works, vol. 31, p. 23[7]

Leninist praxis

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Leninism |

|---|

|

Schools of thought

|

Concepts

|

People

|

History

|

Related

|

|

The vanguard party

In Chapter II: "Proletarians and Communists" of The Communist Manifesto (1848), Marx and Engels presented the idea of the vanguard party as solely qualified to politically lead the proletariat in revolution:

The Communists, therefore, are, on the one hand, practically the most advanced and resolute section of the working-class parties of every country, that section which pushes forward all others; on the other hand, theoretically, they have over the great mass of the proletariat the advantage of clearly understanding the lines of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement. The immediate aim of the Communists is the same as that of all other proletarian parties: Formation of the proletariat into a class, overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy, conquest of political power by the proletariat.

Hence, the purpose of the Leninist vanguard party is to establish a democratic dictatorship of the proletariat; supported by the working class, the vanguard party would lead the revolution to depose the incumbent Tsarist government; and then transfer power of government to the working class, which change of ruling class—from bourgeoisie to proletariat—makes possible the full development of socialism.[8] In the pamphlet What Is To Be Done? (1902), Lenin proposed that a revolutionary vanguard party, mostly recruited from the working class, should lead the political campaign because it was the only way that the proletariat could successfully achieve a revolution; unlike the economist campaign of trade-union-struggle advocated by other socialist political parties; and later by the anarcho-syndicalists. Like Marx, Lenin distinguished between the aspects of a revolution, the "economic campaign" (labour strikes for increased wages and work concessions), which featured diffused plural leadership; and the "political campaign" (socialist changes to society), which required the decisive revolutionary leadership of the Bolshevik vanguard party.

- Democratic centralism

As epitomised in the slogan "Freedom in Discussion, Unity in Action", Lenin followed the example of the First International (IWA, International Workingmen's Association, 1864–1876) and organised the Bolsheviks as a democratically centralised vanguard party, wherein free political-speech was recognised legitimate until policy consensus. Afterwards, every member of the party would be expected to uphold the official policy established in consensus. In the pamphlet Freedom to Criticise and Unity of Action (1905), Lenin said:

Of course, the application of this principle in practice will sometimes give rise to disputes and misunderstandings; but only on the basis of this principle can all disputes and all misunderstandings be settled honourably for the Party. [...] The principle of democratic centralism and autonomy for local Party organisations implies universal and full freedom to criticise, so long as this does not disturb the unity of a definite action; it rules out all criticism which disrupts or makes difficult the unity of an action decided on by the Party.[9]

Full, inner-party democratic debate was Bolshevik Party practice under Lenin, even after the banning of party factions in 1921. Although a guiding influence in policy, Lenin did not exercise absolute power and continually debated and discussed to have his point of view accepted. Under Stalin, the inner-party practice of democratic free debate did not continue after the death of Lenin in 1924.

- Revolution

Before the Revolution, despite supporting political reform (including Bolsheviks elected to the Duma, when opportune), Lenin proposed that capitalism could ultimately only be overthrown with revolution, not with gradual reforms—from within (Fabianism) and from without (social democracy)—which would fail because the ruling capitalist social class, who hold economic power (the means of production), determine the nature of political power in a bourgeois society.[10] As epitomised in the slogan "For a Democratic Dictatorship of the Proletariat and Peasantry", a revolution in the underdeveloped Russian Empire required an allied proletariat of town and country (urban workers and peasants) because the urban workers would be too few to successfully assume power in the cities on their own. Moreover, owing to the middle-class aspirations of much of the peasantry, Leon Trotsky proposed that the proletariat should lead the revolution as the only way for it to be truly socialist and democratic. Although Lenin initially disagreed with Trotsky's formulation, he adopted it before the Russian Revolution in October 1917.

Dictatorship of the proletariat

| This article is part of a series on the | ||||||

| Politics of the Soviet Union | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

Leadership

| ||||||

Communist Party

| ||||||

Legislature

| ||||||

Governance

| ||||||

Judiciary

| ||||||

Ideology

| ||||||

Society

| ||||||

| ||||||

In the Russian socialist society, government by direct democracy was effected by elected soviets (workers' councils), which "soviet government" form Lenin described as the manifestation of the Marxist "democratic dictatorship of the proletariat".[11] As political organisations, the soviets would comprise representatives of factory workers' and trade union committees, but would exclude capitalists as a social class in order to ensure the establishment of a proletarian government, by and for the working class and the peasants. About the political disenfranchisement of the Russian capitalist social classes, Lenin said that "depriving the exploiters of the franchise is a purely Russian question, and not a question of the dictatorship of the proletariat, in general. [...] In which countries [...] democracy for the exploiters will be, in one or another form, restricted [...] is a question of the specific national features of this or that capitalism".[12] In chapter five of The State and Revolution (1917), Lenin describes the dictatorship of the proletariat as such:

[...] the organisation of the vanguard of the oppressed as the ruling class for the purpose of crushing the oppressors. [...] An immense expansion of democracy, which for the first time becomes democracy for the poor, democracy for the people, and not democracy for the rich [...] and suppression by force, i.e. exclusion from democracy, for the exploiters and oppressors of the people—this is the change which democracy undergoes during the 'transition' from capitalism to communism.[13]

About democracy, Lenin further stated the following in The State and Revolution:

Democracy for the vast majority of the people, and suppression by force, i.e. exclusion from democracy, of the exploiters and oppressors of the people—this is the change democracy undergoes during the transition from capitalism to communism.

— Collected Works, vol. 25, pp. 461–462[14]

Soviet constitutionalism was the collective government form of the Russian dictatorship of the proletariat, the opposite of the government form of the dictatorship of capital (privately owned means of production) practised in bourgeois democracies. In the soviet political system, the (Leninist) vanguard party would be one of many political parties competing for elected power.[1][11][15] Nevertheless, the circumstances of the Red vs. White Russian Civil War and terrorism by the opposing political parties and in aid of the White Armies' counter-revolution led to the Bolshevik government banning other parties, thus the vanguard party became the sole, legal political party in Russia. Lenin did not regard such political suppression as philosophically inherent to the dictatorship of the proletariat, yet the Stalinists retrospectively claimed that such factional suppression was original to Leninism.[16][17][18]

Economics

The Soviet Union nationalised industry and established a foreign-trade monopoly to allow the productive co-ordination of the national economy and so prevent Russian national industries from competing against each other. To feed the populaces of town and country, Lenin instituted War Communism (1918–1921) as a necessary condition—adequate supplies of food and weapons—for fighting the Russian Civil War (1917–1923).[15] Later in March 1921, he established the New Economic Policy (NEP, 1921–1929), which allowed measures of private commerce, internal free trade and replaced grain requisitions with an agricultural tax under the management of state banks. The purpose of the NEP was to resolve food-shortage riots among the peasantry and allowed measures of private enterprise, wherein the profit motive encouraged the peasants to harvest the crops required to feed the people of town and country; and to economically re-establish the urban working class, who had lost many men (workers) to the counter-revolutionary Civil War.[19][20] With the NEP, the socialist nationalisation of the economy could then be developed to industrialise Russia, strengthen the working class and raise standards of living, thus the NEP would advance socialism against capitalism. Lenin regarded the appearance of new socialist states in the developed countries as necessary to the strengthening Russia's economy and the eventual development of socialism. In that, he was encouraged by the German Revolution of 1918–1919, the Italian insurrection and general strikes of 1920 and industrial unrest in Britain, France and the United States.

National self-determination

Lenin recognized and accepted the existence of nationalism among oppressed peoples, advocated their national rights to self-determination and opposed the ethnic chauvinism of "Greater Russia" because such ethnocentrism was a cultural obstacle to establishing the proletarian dictatorship in the territories of the deposed Russian Empire (1721–1917).[21][22] In The Right of Nations to Self-determination (1914), Lenin said:

We fight against the privileges and violence of the oppressor nation, and do not in any way condone strivings for privileges on the part of the oppressed nation. [...] The bourgeois nationalism of any oppressed nation has a general democratic content that is directed against oppression, and it is this content that we unconditionally support. At the same time, we strictly distinguish it from the tendency towards national exclusiveness. [...] Can a nation be free if it oppresses other nations? It cannot.[23]

The internationalist philosophies of Bolshevism and of Marxism are based upon class struggle transcending nationalism, ethnocentrism and religion, which are intellectual obstacles to class consciousness because the bourgeois ruling classes manipulated said cultural status quo to politically divide the proletarian working classes. To overcome the political barrier of nationalism, Lenin said it was necessary to acknowledge the existence of nationalism among oppressed peoples and to guarantee their national independence as the right of secession; and that based upon national self-determination, it was natural for socialist states to transcend nationalism and form a federation.[24] In The Question of Nationalities, or "Autonomisation" (1923), Lenin said the following:

[...] nothing holds up the development and strengthening of proletarian class solidarity so much as national injustice; "offended" nationals are not sensitive to anything, so much as to the feeling of equality, and the violation of this equality, if only through negligence or jest—to the violation of that equality by their proletarian comrades.[25]

Socialist culture

The role of the Marxist vanguard party was to politically educate the workers and peasants to dispel the societal false consciousness of religion and nationalism that constitute the cultural status quo taught by the bourgeoisie to the proletariat to facilitate their economic exploitation of peasant and worker. Influenced by Lenin, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party stated that the development of the socialist workers' culture should not be "hamstrung from above" and opposed the Proletkult (1917–1925) organisational control of the national culture.[26]

Leninism after 1924

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism–Leninism |

|---|

|

Concepts

|

Variants

|

People

|

Literature

|

History

|

Related topics

|

|

In post-Revolutionary Russia, Stalinism (socialism in one country) and Trotskyism (permanent world revolution) were the principal philosophies of communism that claimed legitimate ideological descent from Leninism, thus within the Communist Party, each ideological faction denied the political legitimacy of the opposing faction.[27]

- Lenin vs. Stalin

Until shortly before his death, Lenin worked to counter the disproportionate political influence of Joseph Stalin in the Communist Party and in the bureaucracy of the Soviet government, partly because of abuses he had committed against the populace of Georgia and partly because the autocratic Stalin had accumulated administrative power disproportionate to his office of General Secretary of the Communist Party.[28][29] The counter-action against Stalin aligned with Lenin's advocacy of the right of self-determination for the national and ethnic groups of the former Tsarist Empire, which was a key theoretic concept of Leninism.[29] Lenin warned that Stalin has "unlimited authority concentrated in his hands, and I am not sure whether he will always be capable of using that authority with sufficient caution" and formed a factional bloc with Leon Trotsky to remove Stalin as the General Secretary of the Communist Party.[18][30]

To that end followed proposals reducing the administrative powers of party posts in order to reduce bureaucratic influence upon the policies of the Communist Party. Lenin advised Trotsky to emphasize Stalin's recent bureaucratic alignment in such matters (e.g. undermining the anti-bureaucratic workers' and peasants' Inspection) and argued to depose Stalin as General Secretary. Despite advice to refuse "any rotten compromise", Trotsky did not heed Lenin's advice and General Secretary Stalin retained power over the Communist Party and the bureaucracy of the soviet government.[18]

- Trotskyism vs. Stalinism

After Lenin's death (21 January 1924), Trotsky ideologically battled the influence of Stalin, who formed ruling blocs within the Russian Communist Party (with Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, then with Nikolai Bukharin and then by himself) and so determined soviet government policy from 1924 onwards. The ruling blocs continually denied Stalin's opponents the right to organise as an opposition faction within the party—thus the re-instatement of democratic centralism and free speech within the Communist Party were key arguments of Trotsky's Left Opposition and the later Joint Opposition.[18][31]

Leon Trotsky was exiled from Russia after losing to Joseph Stalin in the factional politics of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

In the course of instituting government policy, Stalin promoted the doctrine of socialism in one country (adopted 1925), wherein the Soviet Union would establish socialism upon Russia's economic foundations (and support socialist revolutions elsewhere). Conversely, Trotsky held that socialism in one country would economically constrain the industrial development of the Soviet Union and thus required assistance from the new socialist countries that had arisen in the developed world—which was essential for maintaining Soviet democracy—in 1924 much undermined by civil war and counter-revolution. Furthermore, Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution proposed that socialist revolutions in underdeveloped countries would go further towards dismantling feudal régimes and establish socialist democracies that would not pass through a capitalist stage of development and government. Hence, revolutionary workers should politically ally with peasant political organisations, but not with capitalist political parties. In contrast, Stalin and allies proposed that alliances with capitalist political parties were essential to realising a revolution where communists were too few. However, said Stalinist practice failed, especially in the Northern Expedition portion of the Chinese Revolution (1925–1927), wherein it resulted in the right-wing Kuomintang's massacre of the Chinese Communist Party. Despite the failure, Stalin's policy of mixed-ideology political alliances nonetheless became Comintern policy.

- The Oppositionists

The "Old Bolsheviks" (Stalin, Lenin and Mikhail Kalinin, pictured in 1919) were members of the Bolshevik Party before the Russian Revolution

Until exiled from Russia in 1929, Trotsky helped develop and led the Left Opposition (and the later Joint Opposition) with members of the Workers' Opposition, the Decembrists and (later) the Zinovievists.[18] Trotskyism ideologically predominated the political platform of the Left Opposition, which demanded the restoration of soviet democracy, the expansion of democratic centralism in the Communist Party, national industrialisation, international permanent revolution and socialist internationalism. The Trotskyist demands countered Stalin's political dominance of the Russian Communist Party, which was officially characterised by the "cult of Lenin", the rejection of permanent revolution and the doctrine of socialism in one country. The Stalinist economic policy vacillated between appeasing capitalist kulak interests in the countryside and destroying them. Initially, the Stalinists also rejected the national industrialisation of Russia, but then pursued it in full, sometimes brutally. In both cases, the Left Opposition denounced the regressive nature of the policy towards the kulak social class of wealthy peasants and the brutality of forced industrialisation. Trotsky described the vacillating Stalinist policy as a symptom of the undemocratic nature of a ruling bureaucracy.[32]

During the 1920s and the 1930s, Stalin fought and defeated the political influence of Trotsky and of the Trotskyists in Russia, by means of slander, antisemitism, programmed censorship, expulsions, exile (internal and external) and imprisonment. The anti–Trotsky campaign culminated in the executions (official and unofficial) of the Moscow Trials (1936–1938), which were part of the Great Purge of Old Bolsheviks (who had led the Revolution).[18][33] Once established as ruler of the Soviet Union, General Secretary Stalin re-titled the official socialism in one country doctrine as Marxism–Leninism to establish ideologic continuity with Leninism whilst opponents continued calling it Stalinism.

Philosophic successors

In political practice, Leninism (vanguard-party revolution), despite its origin as communist revolutionary praxis, was adopted throughout the political spectrum.

- In China, the Communist Party of China is organised as a Leninist vanguard party, based upon Maoism (Mao Zedong Thought), the Chinese practical application of Marxism–Leninism, that is socialism with Chinese characteristics.[34]

- In Singapore, the People's Action Party (PAP) was organised as a Leninist political party featuring internal democracy. The PAP initiated single-party dominance in the government and popular politics of Singapore.[35]

In the event, the practical application of Maoism to the socio-economic conditions of Third World countries produced revolutionary vanguard parties, such as the Communist Party of Peru – Red Fatherland.[36]

Criticism

In The Nationalities Question in the Russian Revolution (1918), Marxist Rosa Luxemburg criticized the Bolsheviks and their policies for: the suppression of the All Russian Constituent Assembly (January 1918); the partitioning of the feudal estates to the peasant communes; and the right of self-determination of every national people of the Russias. Luxemburg said that the strategic (geopolitical) mistakes of the Bolsheviks would create great dangers for the Russian Revolution, such as the bureaucratisation that would arise to administrate the oversized country that was Bolshevik Russia.[37] In defence of expedient revolutionary practise, Lenin criticised in "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder (1920) the political and ideological complaints of the anti-Bolshevik critics who claimed ideologically correct stances that were to the political-left of Lenin.

In Marxist philosophy, the term "left communism" identifies a range of communist political perspectives that are left-wing among communists. Left communism criticizes the ideology that the Bolshevik Party practiced as a revolutionary vanguard at certain periods of their history. Ideologically, left communists present their perspective and approach as more authentically Marxist and more oriented to the proletariat than it is the Leninism of the Communist International at their first (1919) and second (1920) congresses. Proponents of left communism include Amadeo Bordiga, Herman Gorter, Antonie Pannekoek, Otto Rühle, Sylvia Pankhurst and Paul Mattick.[38]

Historically, the Dutch–German communist left has been most critical of Lenin and Leninism.[39][40][41] The Italian communist left instead still identified as Leninists; Bordiga said: "All this work of demolishing opportunism and "deviationism" (Lenin: What Is To Be Done?) is today the basis of party activity. The party follows revolutionary tradition and experiences in this work during these periods of revolutionary reflux and the proliferation of opportunist theories which had as their violent and inflexible opponents Marx, Engels, Lenin and the Italian Left.".[42] Paul Mattick continues in the council communist tradition which begun by the Dutch–German left and so is also critical of Leninism.[43] Contemporary left-communist organisations, such as the Internationalist Communist Tendency and the International Communist Current, view Lenin as an important and influential theorist, but remain critical of Leninism as political praxis.[44][45][46] The Bordigist ideology of the International Communist Party follow Bordiga's strict adherence to Leninism. The recent communisation current has been influenced by left communism and is critical of Lenin and Leninism, being more ideologically aligned with the Dutch–German left than the Italian left, wherein the theorist of communisation Gilles Dauvé criticised Leninism as a "by-product of Kautskyism".[47]

In The Soviet Union Versus Socialism (1986), Noam Chomsky argued that Stalinism was a logical extension of Leninism, and not an ideological deviation from Lenin's policies. It resulted in collectivization and enforced the law with a police state, functions of the state continually supported with a totalitarian political ideology.[48][49]

See also

- Anti-Leninism

- Democratic centralism

- "He who does not work neither shall he eat"

- Lenin's national policy

- New Economic Policy

- One Partyism

The State and Revolution (1917)- Yellow socialism

References

^ abc The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought Third Edition (1999) pp. 476–477.

^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition. (1994), p. 1,558.

^ Lih, Lars (2005). Lenin Rediscovered: What is to be Done? in Context. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-13120-0..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Faces of Janus p. 133.

^ Tomasic, D. "The Impact of Russian Culture on Soviet Communism" (1953), The Western Political Quarterly, vol. 6, No. 4 December, pp. 808–809.

^ Lenin, V. I., United States of Europe Slogan, Collected Works, vol. 18, p. 232.

^ Lenin, Vladimir (1920). "No Compromises?". Left-Wing Communism: an Infantile Disorder. Soviet Union: Progress Publishers. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

^ Townson, D. The New Penguin Dictionary of Modern History: 1789–1945. London:1994. pp. 462–464.

^ Lenin, V.I. (1905) Freedom to Criticise and Unity of Action, from Lenin Collected Works, Progress Publishers, 1965, Moscow, Volume 10, pages 442-443. Available online at Marxists.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

^ Lenin, V.I. (1917) The State and Revolution, from Lenin Collected Works, Volume 25, pp. 381-492. Available online at "The State and Revolution". Marxists.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

^ ab Isaac Deutscher, 1954. The Prophet Armed: Trotsky 1879-1921, Oxford University Press.

^ Lenin, V.I. "The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky", from Lenin's Collected Works, Progress Publishers, Moscow, Volume 28, 1974, pages 227–325. Available online at Marxists.org. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

^ Hill, Christopher. Lenin and the Russian Revolution (1971). Penguin Books. London p. 86.

^ Marx Engels Lenin on Scientific Socialism. Moscow: Novosti Press Ajency Publishing House. 1974.

^ ab Carr, Edward Hallett. The Russian Revolution From Lenin to Stalin: 1917-1929. (1979).

^ Lewin, Moshe. Lenin's Last Struggle. (1969).

^ Carr, Edward Hallett. The Russian Revolution, from Lenin to Stalin: 1917–1929. (1979).

^ abcdef Deutscher, Isaac 1959. The Prophet Unarmed: Trotsky 1921-1929, Oxford University Press.

^ Dictionary of Historical Terms Chris Cook, editor (1983) Peter Bedrick Books:New York p. 205.

^ Lenin, V.I. The New Economic Policy and the Tasks of the Political Education Departments, Report to the Second All-Russia Congress of Political Education Departments, 17 October 1921, from Lenin's Collected Works, 2nd English Edition, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1965, Volume 33, pp. 60–79. Available at Marxists.org. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

^ Lenin, V.I. (1914) The Right of Nations to Self-Determination, from Lenin's Collected Works, Progress Publishers, 1972, Moscow, Volume 20, pp. 393-454. Available online at Marxists.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011)

^ Harding, Neil (ed.) The State in Socialist Society, second edition (1984) St. Antony's College: Oxford, p. 189.

^ Lenin, V.I. (1914) The Right of Nations to Self-determination, Chapter 4: 4. "Practicality" in The National Question; from Lenin's Collected Works, Progress Publishers, 1972, Moscow, Volume 20, pp. 393–454. Available online at Marxists.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

^ Lewin, Moshe. Lenin's Last Struggle (1969).

^ Lenin, V.I. (1923) "The Question of Nationalities or 'Autonomisation'" in "Last Testament' Letters to the Congress", from Lenin Collected Works, Volume 36, pp. 593–611. Available online at Marxists.orgm. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

^ Central Committee, On Proletcult Organisations, Pravda No. 270, 1 December 1920.

^ Chambers Dictionary of World History (2000) p. 837.

^ Lewin, Moshe. Lenin's Last Struggle. (1969).

^ ab Carr, Edward Hallett. The Russian Revolution From Lenin to Stalin: 1917-1929. (1979).

^ Lenin, V.I. 1923-24 "Last Testament" Letters to the Congress, in Lenin Collected Works, Volume 36 pp. 593–611. Available online at Marxists.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

^ Trotsky, Leon 1927. Platform of the Joint Opposition. Available online at Marxists.rog. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

^ Trotsky, L.D. (1938) The Revolution Betrayed.

^ Rogovin, Vadim Z. Stalin's Terror of 1937-1938: Political Genocide in the USSR. (2009) translated to English by Frederick S. Choate, from the Russian-language Party of the Executed by Vadim Z. Rogovin.

^ Zheng Yongnian, The Chinese Communist Party as Organizational Emperor (2009) p. 61.

^ Peter Wilson, Economic growth and development in Singapore (2002) p. 30.

^ Kenneth M. Roberts, Deepening Democracy?: The Modern Left and Social Movements in Chile and Peru (1988) pp 288–289.

^ "The Nationalities Question in the Russian Revolution (Rosa Luxemburg, 1918)". Libcom.org. 11 July 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

^ The 'Advance Without Authority': Post-modernism, Libertarian Socialism and Intellectuals by Chamsy Ojeili, Democracy & Nature, vol. 7, no. 3, 2001.

^ "Herman Gorter, Open Letter to Comrade Lenin, 1920".

^ "Anton Pannekoek: Lenin As Philosopher (1938)".

^ "Rühle: Struggle Against Bolshevism (Intro)".

^ "Fundamental Theses of the Party by Amadeo Bordiga 1951".

^ "The Leninn Legend by Paul Mattick".

^ "The Significance of the Russian Revolution for Today".

^ "Lenin's Legacy".

^ "Have we become "Leninists"? - part 1".

^ "Gilles Dauvé - The Renegade Kautsky and his Disciple Lenin".

^ Steven Merritt Miner (11 May 2003). "The Other Killing Machine". The New York Times. The New York Times.

^ Noam Chomsky (Spring–Summer 1986). "The Soviet Union Versus Socialism". Our Generation.

Further reading

- Selected works by Vladimir Lenin

The Development of Capitalism in Russia, 1899.

What Is To Be Done? Burning Questions of Our Movement, 1902.

The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism, 1913.

The Right of Nations to Self-Determination, 1914.

Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, 1917.

The State and Revolution, 1917.

The Tasks of the Proletariat in the Present Revolution (The "April Theses"), 1917.

"Left-Wing" Childishness and the Petty Bourgois Mentality, 1918.

Left-Wing Communism: an Infantile Disorder, 1920.

"Last Testament" Letters to the Congress, 1923–1924.

- Histories

- Isaac Deutscher. The Prophet Armed: Trotsky 1879–1921, 1954.

- Isaac Deutscher. The Prophet Unarmed: Trotsky 1921–1929, 1959.

- Moshe Lewin. Lenin's Last Struggle, 1969.

- Edward Hallett Carr. The Russian Revolution From Lenin to Stalin: 1917–1929, 1979.

- Other authors

- Paul Blackledge. What was Done an extended review of Lars Lih's Lenin Rediscovered from International Socialism.

- Sebastian Budgen, Stathis Kouvelakis, Slavoj Žižek (eds). Lenin Reloaded: Toward a Politics of Truth. Durham: Duke University Press. 2007.

ISBN 978-0822339410.

Marcel Liebman. Leninism Under Lenin. The Merlin Press. 1980.

ISBN 0-85036-261-X.

Roy Medvedev. Leninism and Western Socialism. Verso Books. 1981.

ISBN 0-86091-739-8.- Neil Harding. Leninism. Duke University Press. 1996.

ISBN 0-8223-1867-9.

Joseph Stalin. Foundations of Leninism. University Press of the Pacific. 2001.

ISBN 0-89875-212-4.

CLR James. Notes on Dialectics: Hegel, Marx, Lenin. Pluto Press. 2005.

ISBN 0-7453-2491-6.

Edmund Wilson. To the Finland Station: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History. Phoenix Press. 2004.

ISBN 0-7538-1800-0.

Non-Leninist Marxism: Writings on the Workers Councils (texts by Gorter, Pannekoek, Pankhurst and Rühle), Red and Black Publishers, St Petersburg, Florida, 2007.

ISBN 978-0-9791813-6-8.

Paul Le Blanc. Lenin and the Revolutionary Party. Humanities Press International, Inc. 1990.

ISBN 0-391-03604-1.

A. James Gregor. The Faces of Janus. Yale University Press. 2000.

ISBN 0-300-10602-5.

Lenin, V.I.; Žižek, Slavoj (2017). Lenin 2017: Remembering, Repeating, and Working Through. Verso. ISBN 978-1786631886.

Kolakowski, Leszek . Main Currents of Marxism Volume 2. Clarendom Press. 1978.

Marcuse, Herbert. Soviet Marxism: An Analysis, Columbia University Press. 1958.

Lukacs, Georg. History and Class Consciousness. Mit Press. 1972.

External links

Works by Vladimir Lenin:

What Is To Be Done?.

Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism.

The State and Revolution.

"The Lenin Archive". Marxists.org.

"First Conference of the Communist International".

Other thematic links:

"Marcel Liebman on Lenin and democracy".

"An excerpt on Leninism and State Capitalism from the work of Noam Chomsky".

Rosa Luxemburg. "Organizational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy".

Karl Korsch. "Lenin's Philosophy".

"Cyber Leninism".

"Leninist Ebooks".

Anton Pannekoek. "Lenin as a Philosopher".

Paul Mattick. "The Lenin Legend".

Paul Craig Roberts. "Dead Labor: Marx and Lenin Reconsidered".