Kalenjin people

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 4,967,328[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Kalenjin | |

| Religion | |

Christianity, African Traditional Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Maasai, Samburu, Turkana, other Nilotic peoples |

The Kalenjin are an ethnolinguistic group indigenous to Kenya, mainly in what was formerly the Rift Valley Province. They are estimated to number a little over 4.9 million individuals as per the Kenyan 2009 census[2] and are divided into the Kipsigis, Nandi, Keiyo, Marakwet, Sabaot, Pokots, Tugen, Terik and Ogiek. They speak the Kalenjin language, which belongs to the Nilotic group within the wider Nilo-Saharan family.

Contents

1 Prehistory

1.1 Origins

1.2 Elmenteitan

1.3 Proto-Sirikwa

1.4 Sirikwa Era

2 History

2.1 The Maasai Era

2.2 Traditional way of life

2.3 Resistance to British Rule

2.4 Colonial Period

2.4.1 Politics & Identity

2.4.2 Religion

2.4.3 Food

2.4.4 Literacy

3 Recent History

3.1 Demographics

3.1.1 Subdivisions

3.2 Economic activity

4 Culture

4.1 Language

4.2 Naming conventions

4.2.1 Arap

4.2.2 Common names

4.3 Customs

4.3.1 Initiation

4.3.2 Marriage

4.4 Religion

4.5 Elders

4.6 Folklore

4.7 Literature

4.8 Music

4.9 Science

4.10 Cuisine

4.11 Sport

5 See also

6 Notes

7 Bibliography

8 External links

Prehistory

Origins

Areas where Nilotic languages are spoken.

Linguistic evidence points to the eastern Middle Nile Basin south of the Abbai River, as the nursery of the Nilotic languages. That is to say south-east of present-day Khartoum.[3]

It is thought that beginning in the second millennium B.C., particular Nilotic speaking communities began to move southward into present day South Sudan where most settled and that the societies today referred to as the Southern Nilotes pushed further on, reaching what is present day north-eastern Uganda by 1000 B.C.[3]

Ehret proposes that between 1000 and 700 BC, the Southern Nilotic speaking communities, who kept domestic stock and possibly cultivated sorghum and finger millet,[4]

lived next to an Eastern Cushitic speaking community with whom they had significant cultural interaction. The general location of this point of cultural exchange being somewhere near the common border between Sudan, Uganda, Kenya and Ethiopia.

He suggests that the cultural exchange perceived in borrowed loan words, adoption of the practice of circumcision and the cyclical system of age-set organisation dates to this period.[5]

Elmenteitan

The beads and pendants forming this c.3,000 year old neck chain are of the Elmenteitan culture and were among the finds at Njoro River Cave

The arrival of the Southern Nilotes on the East African archaeological scene is correlated with the appearance of the prehistoric lithic industry and pottery tradition referred to as the Elmenteitan culture.[6] The bearers of the Elmenteitan culture developed a distinct pattern of land use, hunting and pastoralism on the western plains of Kenya during the East African Pastoral Neolithic. It's earliest recorded appearance dates to the ninth century BC.[7]

Around the fifth and sixth centuries BC, the Elmenteitain culture split into two major divisions, linguistically the proto-Kalenjin and the proto-Datooga. The former took shape among those residing to the north of the Mau range while the latter took shape among sections that moved into the Mara and Loita plains south of the western highlands.[8]

Certain distinct traits of the Southern Nilotes, notably in pottery styles, lithic industry and burial practices, are evident in the archaeological record.[9][10][11]

Proto-Sirikwa

The material culture referred to as Sirikwa is seen as a development from the local pastoral neolithic (i.e. Elmenteitan culture), as well as a locally limited transition from the Neolithic to the Iron Age.[12]

Radiocarbon dating of archaeological excavations done in Rongai (Deloraine) have ranged in date from around 985 to 1300 A.D and have been associated with the early development phase of the Sirikwa culture.[13] Lithics from Deloraine Farm site show that people were abandoning previous technological strategies in favor of more expedient tool production as iron was entering common use. The spread of iron technology led to the abandonment of many aspects of Pastoral Neolithic material culture and practices.[14]

From the Central Rift, the culture radiated outwards toward the western highlands, the Mt. Elgon region and possibly into Uganda.[15]

Sirikwa Era

By the thirteenth century the fully developed Sirikwa societies emerge to become the dominant population of the western highlands of Kenya for the next six centuries.

Archaeological evidence indicates a highly sedentary way of life and a cultural commitment to a closed defensive system for both the community and their livestock during the Sirikwa era. Family homesteads featured small individual family stock pens, elaborate gate-works and sentry points and houses facing into the homestead; defensive methods primarily designed to proof against individual thieves or small groups of rustlers hoping to succeed by stealth.[16] A commitment to trade in this period is also highlighted by fact that the ancient caravan routes from the Swahili coast led to the territories of the Kalenjin ancestors.[17]

At their greatest extent, their territories covered the highlands from the Chepalungu and Mau forests northwards as far as the Cherangany Hills and Mount Elgon. There was also a south-eastern projection, at least in the early period, into the elevated Rift grasslands of Nakuru which was taken over permanently by the Maasai, probably no later than the seventeenth century. Here Kalenjin place names seem to have been superseded in the main by Maasai names[18] notably Mount Suswa (Kalenjin – place of grass) which was in the process of acquiring its Maasai name, Ol-doinyo Nanyokie, the red mountain during the period of European exploration.[19]

History

The Maasai Era

The adoption of Zebu cattle is seen as one of the drivers of change that led to the Maasai era

The Ateker-speakers, represented in the present-day by the Turkana, were the last of the indigenous ethnic groups to arrive in modern-day Kenya and their rise had far reaching effects on neighboring peoples, most notably the Maa and Kalenjin speakers. Impelled by demographic and ecological pressures sparked by the Aoyate (the long dry time) drought, they began encroaching on the territory of Sirikwa era Sengwer and Loikop thus setting off a period of widespread chaos and warfare[20].

As the Maasai were displaced from the homeland in the north of Kenya, they developed or borrowed an array of social and political changes that allowed them to expand swiftly, transforming them in a few generations from an obscure group to the regions dominant society.[21]

These cultural changes, particularly the innovation of heavier and deadlier spears amongst the Maasai led to significant changes in methods and scale of raiding bringing about the Maasai era of the late-18th and 19th centuries. The change in methods introduced by the Maasai however consisted of more than simply their possession of heavier, and more deadly spears. There were more fundamental differences of strategy, in fighting and defense and also in organization of settlements and of political life.[16]

In the Maasai era, guarding cattle on the plateaus depended less on elaborate defenses and more on mobility and cooperation, both of these being combined with grazing and herd-management strategies. The practice of the later Kalenjin – that is, after they had abandoned the Sirikwa pattern and had ceased in effect to be Sirikwa – illustrates this change vividly. On their reduced pastures, notably on the borders of the Uasin Gishu plateau, they would when bodies of raiders approached relay the alarm from ridge to ridge, so that the herds could be combined and rushed to the cover of the forests. There, the approaches to the glades would be defended by concealed archers, and the advantage would be turned against the spears of the plains warriors.[22]

More than any of the other sections, the Nandi and Kipsigis, in response to Maasai expansion, borrowed from the Maasai some of the traits that would distinguish them from other Kalenjin: large-scale economic dependence on herding, military organization and aggressive cattle raiding, as well as centralized religious-political leadership. The family that established the office of Orkoiyot (warlord/diviner) among both the Nandi and Kipsigis were nineteenth-century Sengwer immigrants. By the mid-1800's, both the Nandi and Kipsigis were expanding at the expense of the Maasai. This process was halted in 1905 by the imposition of British colonial rule.[23]

Traditional way of life

The Maasai era saw the formation of the new Kalenjin societies that at their core remained the same; these new societies, like the Sirikwa societies of the middle ages and after and the proto-Sirikwa before them were primarily semi-nomadic pastoralists. They were still raising cattle, sheep and goats and cultivating sorghum and pearl millet on the western highlands of Kenya[24] as they had since at least the last millennium B.C when they arrived.[25]

A territory that was not as a whole recognized as a geographic locality, though the various Kalenjin sub-tribes did have a similar set of classifications of geographic localities within their respective tribal lands.

Of these geographic classifications, the Kokwet was the most significant political and judicial unit among the Kalenjin. The governing body of each kokwet was its kokwet council; the word kokwet was in fact variously used to mean the whole neighbourhood, its council and the place where the council met.

Resistance to British Rule

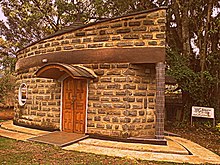

Koitalel Arap Samoei Mausoleum and Museum in Nandi Hills, Kenya

In the later decades of the 19th century, at the time when the early European explorers started advancing into the interior of Kenya. They first arrived in territory occupied by the Lembus People and faced fierce resistance. In the late 19th century, the Lembus fought with the British to protect their lands and more so their forest (Lembus Forest). The Lembus resistance eventually led to a peace treaty being signed between the British and the Lembus in a ceremony at Kerkwony in Eldama Ravine.

The Nandi people were also resisting the British almost the same time with Lembus. Led by Koitalel Arap Samoei, the Nandi resisted the British by waging a hard fought war. Thompson in 1883 was warned to avoid the country of the Nandi, who were known for attacks on strangers and caravans that would attempt to scale the great lands of the Mau.[26]

Matson, in his account of the resistance, shows 'how the irresponsible actions of two British traders, Dick and West, quickly upset the precarious modus vivendi between the Nandi and incoming British'.[27] This would cause more than a decade of conflict led on the Nandi side by Koitalel Arap Samoei, the Nandi Orkoiyot at the time.

Colonial Period

Politics & Identity

Until the mid-20th century, the Kalenjin did not have a common name known to the external world and were usually referred to as the 'Nandi-speaking tribes' by scholars and colonial administration officials.[28]

Kenya African Democratic Union Eldoret Branch

Starting in the 1940s, individuals from the various 'Nandi-speaking tribes' who had been drafted to fight in World War II (1939–1945) began using the term Kale or Kore (a term that denoted scarification of a warrior who had killed an enemy in battle) to refer to themselves. At about the same time, a popular local radio broadcaster by the name of John Chemallan would introduce his wartime broadcasts show with the phrase Kalenjok meaning "I tell You" (when said to many people). This would influence a group of fourteen young 'Nandi-speaking' men attending Alliance School and who were trying to find a name for their peer group. They would call it Kalenjin meaning "I tell you" (when said to one person). The word Kalenjin was gaining currency as a term to denote all the 'Nandi-speaking' tribes. This identity would be consolidated with the founding of the Kalenjin Union in Eldoret in 1948 and the publication of a monthly magazine called Kalenjin in the 1950s.[29]

In 1955 when Mzee Tameno, a Maasai and member of the Legislative Assembly (LEGCO) for Rift Valley, tendered his resignation, the Kalenjin presented one candidate to replace him; Daniel Toroitich arap Moi.[30]

By 1960, concerned with the dominance of the Luo and Kikuyu, Arap Moi and Ronald Ngala formed KADU to defend the interests of the countries smaller tribes. They campaigned on a platform of majimboism (devolution) during the 1963 elections but lost to KANU. Shortly after independence in December 1963, Kenyatta convinced Moi to dissolve KADU. This was done in 1964 when KADU dissolved and joined KANU.

Religion

Christianity was introduced and rapidly spread through Kalenjin speaking areas during the colonial period. Traditional Kalenjin religion which was undergoing separate change saw a corresponding decline in this time.[31]

Food

The colonial period saw the introduction of tea cultivation on a large scale in the Kericho and Nandi highlands. These regions have since played a significant role in establishing Kenya as the world’s leading exporter of tea and also in establishing a tea-drinking culture among the Kalenjin. This period also saw the introduction of the mid-day meal as well as the addition of wheat based foods such as bread and less often pancakes and maandazi to the morning meal[32].

Literacy

A significant cultural change of the colonial period was the introduction and adoption of the Latin script for transcribing first the Bible, and later Kalenjin lore and history.[33]

Recent History

Wheat plantation in Uasin Gishu

Demographics

According to Kenya's 2009 census, Kalenjin speakers number 4,967,328 individuals, making it the third largest ethnic group in Kenya after the Kikuyu and the Luhya.[2]

Subdivisions

There are several tribal groupings within the Kalenjin: They include the Keiyo, Endorois, Kipsigis, Marakwet, Nandi, Pokot, Terik, Tugen and Sebei.

Economic activity

A significant majority of Kalenjin speakers are primarily subsistence farmers, they cultivate grains such as maize and wheat and to a lesser extent sorghum and millet or practice a pastoralist lifestyle; rearing beef, goats and sheep for meat production. Equally large numbers practice a combination of both farming and livestock (often dairy cattle) rearing[34]. The counties of Uasin Gishu, Trans Nzoia and to a lesser extent Nakuru are often referred to as Kenya's grain-basket counties and are responsible for supplying much of the country's grain requirements.

Meat products from the northern areas of West Pokot and Baringo are particularly appreciated for their flavor and are favored in the Rift for the preparation of nyama choma[35].

A significant number of Kalenjin have moved to Kenya's cities where large numbers are employed in the Kenyan Government, the Army, Police Force, the banking and finance industry as well as in business.

Culture

Contemporary Kalenjin culture is a product of its heritage, the suite of cultural adoptions of the British colonial period and modern Kenyan identity from which it borrows and adds to.

The exploits of Kalenjin athletes form part of Kenyan identity

Language

The Kalenjin speak Kalenjin languages as mother tongues. The language grouping belongs to the Nilo-Saharan family. The majority of Kalenjin speakers are found in Kenya with smaller populations in Tanzania (e.g., Akie) and Uganda (e.g., Kupsabiny).

Kiswahili and English, both Kenyan national languages are widely spoken as second and third languages by most Kalenjin speakers and as first and second languages by some Kalenjin[36].

Naming conventions

The Kalenjin traditionally have two primary names for the individual though in the past additional praise names were sometimes acquired through various acts of courage or community service. A previously common example of the latter was Barngetuny (one who killed a lion). In contemporary times a Christian or Arabic name is also given at birth such that most Kalenjin today have three names with the patronym Arap in some cases being acquired later in life e.g Alfred Kirwa Yego and Daniel Toroitch arap Moi.

An individual is given a personal name at birth and this is determined by the circumstance of their birth. For most Kalenjin speaking communities i.e Kalenjin in Kenya as well as Murle in Ethiopia, Sebei of Uganda, Datooga, Akie and Aramanik of Tanzania, masculine names are often prefixed with Kip- or Ki- though there are exceptions to the rule e.g Cheruiyot, Chepkwony, Chelanga etc. Feminine names in turn are often prefixed with Chep- or Che- though among the Tugen and Keiyo, the prefix Kip- may in some cases denote both males and females. The personal name would thus be derived through adding the relevant prefix to the description of the circumstance of birth, for example a child born in the evening (lagat) might be called Kiplagat or Chelagat.

The tradition of giving a family surname to an individual dates to the colonial period and in most cases the surnames in use today were the second names of the family patriarch of two to four generations ago. Traditionally an individual acquired their father's name after their initiation. Females took on their father's name e.g Cheptoo Lagat being the daughter of Lagat and Cheptoo Kiplagat being the daughter of Kiplgat while males took on just the descriptor portion of the father's name such that the Kiprono son of Kiplagat would become Kiprono arap Lagat.[37][38][39]

Arap

Arap is patronym meaning 'son of'. It was traditionally given following the labetab eun (kelab eun) [40] ceremony and all initiates would after the ceremony acquire their fathers name e.g Toroitich son of Kimoi and Kipkirui son of Kiprotich would after the ceremony be Toroitich arap Moi and Kipkirui arap Rotich. In modern times it is confined to progressing age-sets independent of the individual initiation ceremony such that if the current age-set is Nyongi, all individuals of preceding age-sets may use the term Arap.[41]

Common names

Customs

Initiation

The initiation process is a key component of Kalenjin identity[42]. Among males, the circumcision process is seen as signifying one's transition from boyhood to manhood and is taken very seriously[43]. On the whole the process still occurs during a boys pre-teen/early teenage years though significant differences are emerging in practice. Much esotericism is still attended to in the traditional practice of initiation and there was great uproar amongst Kalenjin elders in 2013 when aspects of the tradition were openly inquired into at the International Court[44]. Conversely a number of contemporary Kalenjin have the circumcision process carried out in hospital as a standard surgical procedure and various models of the learning process have emerged to complement the modern practice. For both orthodox and urban traditions however the use of ibinwek is in decline and the date has been moved from the traditional September/October festive season to December to coincide with the Kenyan school calendar.

The female circumcision process is perceived negatively in the modern world (see: FGM) and various campaigns are being carried out with the intention of eradicating the practice among the Kalenjin[45]. A notable anti-FGM crusader is Hon. Linah Jebii Kilimo.

Marriage

The contemporary Kalenjin wedding has fewer ceremonies than it did traditionally and they often, though not always, occur on different days;[46]

During the first ceremony, the proposal/show-up (kaayaaet'ap koito), the young man who wants to marry, informs his parents of his intention and they in turn tell their relatives often as part of discussing suitability of the pairing. If they approve, they will go to the girls family for a show-up and to request for the girl's hand in marriage. The parents are usually accompanied by aunts, uncles or even grandparents and the request is often couched as an apology to the prospective brides parents for seeking to take their daughter away from them. If her family agrees to let them have their daughter, a date for a formal engagement is agreed upon. Other than initiating it, the intended groom and prospective bride play no part in this ceremony.[47]

During the second ceremony, the formal engagement (koito), the bridegrooms family goes to the brides home to officially meet her family. The grooms family which includes aunts, uncles, grandparents etc are invited into a room for extensive introductions and dowry negotiations. After the negotiations, a ceremony is held where the bridegroom and bride are given advise on family life by older relatives from both families. Usually symbolic gifts and presents are given to the couple during this ceremony.[48] The koito is often quite colorful and sometimes bears resemblance to a wedding ceremony and it is indeed gaining prominence as the key event since the kaayaaet'ap koito is sometimes merged with it and at other times the tunisiet is foregone in favor of it.[49][50][51]

The third ceremony, the wedding (tunisiet), is a big ceremony where as many relations, neighbors, friends and business partners are invited. In modern iterations, this ceremony often follows the pattern of a regular western wedding; it is usually held in church, where rings are exchanged, is officiated by a pastor and followed by a reception. Traditionally, it was officiated over by an elder and the bride and groom would be blessed by four people carrying bouquets of the sinendet (traditionally auspicious plant) who would form a procession and go round the couple four times and finally the bridegroom and bride would bind a sprig of sekutiet (traditionally auspicious plant) onto each others wrists. This was followed by feasting and dancing.[52]

Religion

Almost all modern Kalenjin are members of an organised religion with the vast majority being Christian and a few identifying as Muslim.[53]

Elders

The Kalenjin have a council of elders composed of members of the various Kalenjin sub-tribes and known as the Myoot Council of Elders. This council was formed in the Kenyan post-independence period[54][55].

Folklore

Nandi Bear

Like all oral societies, the Kalenjin developed a rich collection of folklore. Folk narratives were told to pass on a message and a number featured the Chemosit (Nandi Bear), known in Marakwet as Chebokeri, the dreaded monster that devoured the brains of disobedient children.[56]

The Legend of Cheptalel is fairly common among the Kipsigis and Nandi and the name was adopted from Kalenjin mythology into modern tradition. The fall of the Long’ole Clan is another popular tale based on the true-story of the Louwalan clan of the Pokot. The story is told to warn against pride. In the story, the Long’ole warriors believing they were the mightiest in the land goaded their distant rivals the Maasai into battle. The Maasai, though at first reluctant eventually attacked wiping out the Long’ole clan.[57]

As with other East African communities, the colonial period Misri legend has over time become popular among the Kalenjin and aspects of it have influenced the direction of folkloric and academic studies.[58]

Literature

A number of writers have documented Kalenjin history and culture, notably B. E. Kipkorir,[59][60]Paul Kipchumba, and Ciarunji Chesaina.[61]

Music

Contemporary Kalenjin music has long been influenced by the Kipsigis leading to Kericho's perception as a cultural innovation center[62]. Musical innovation and regional styles however abound across all Kalenjin speaking areas. Popular musicians include Pastor Joel Kimetto (father of Kalenjin Gospel), Mike Rotich, Emmy Kosgei, Maggy Cheruiyot, Josphat Koech Karanja, Lilian Rotich and Barbra Chepkoech[63]. Msupa S and Kipsang represent an emerging generation of Kalenjin pop musicians[64]. Notable stars who have passed on include Diana Chemutai Musila (Chelele), Junior Kotestes and Weldon Cheruiyot (Kanene).[65]

Science

Traditional Kalenjin knowledge was fairly comprehensive in the study and usage of plants for medicinal purposes and a significant trend among some contemporary Kalenjin scientists is the study of this aspect of traditional knowledge.[66][67] One of the more notable Kalenjin scientists is Prof Richard Mibey whose work on the Tami dye helped revive the textile industry in Eldoret and western Kenya in general.[68]

Cuisine

Ugali with beef and sauce. A staple of Kalenjin and African Great Lakes cuisine.

Ugali, known in Kalenjin as kimnyet, served with cooked vegetables such as kale, and milk form the staples of the Kalenjin diet. Less often ugali, rice or chapati, is served with roast meat, usually beef or goat, and occasionally chicken. The traditional ugali, made of millet and sorghum, and known as psong'iot has seen a resurgence in popularity in tandem with global trends towards healthier eating. The traditional drink mursik, and honey, both considered delicacies for a long time remain quite popular.

Combination dishes/mixtures while not considered traditionally Kalenjin are encountered in more cosmopolitan areas. The most common of these is kwankwaniek, a mixture of beans cooked with dried pounded maize kernels (githeri).

Milk or tea may be drunk by adults and children with any meal or snack. Tea (chaik) averages 40% milk by volume and is usually liberally sweetened. If no milk is available tea may be drunk black with sugar though taking tea without milk is considered genuine hardship.[69]

In addition to bread, people routinely buy foodstuffs such as sugar, tea leaves, cooking fat, sodas (most often Orange Fanta and Coca-Cola), and other items that they do not produce themselves.[70]

Sport

The Kalenjin have been called by some "the running tribe." Since the mid-1960s, Kenyan men have earned the largest share of major honours in international athletics (track and field) at distances from 800 meters to the marathon; the vast majority of these Kenyan running stars have been Kalenjin.[71] From 1980 on, about 40% of the top honours available to men in international athletics at these distances (Olympic medals, World Championships medals, and World Cross Country Championships honours) have been earned by Kalenjin.

Paul Tergat setting a new world record to the marathon at Berlin, 2003.

In 2008, Pamela Jelimo became the first Kenyan woman to win a gold medal at the Olympics; she also became the first Kenyan to win the Golden League jackpot in the same year.[72] Since then, Kenyan women have become a major presence in international athletics at the distances; most of these women are Kalenjin.[71] Amby Burfoot of Runner's World stated that the odds of Kenya achieving the success they did at the 1988 Olympics were below 1:160 billion. Kenya had an even more successful Olympics in 2008.

A number of theories explaining the unusual athletic prowess among people from the tribe have been proposed. These include many explanations that apply equally well to other Kenyans or people living elsewhere who are not disproportionately successful athletes, such as that they run to school every day, that they live at relatively high altitude, and that the prize money from races is large compared to typical yearly earnings. One theory is that the Kalenjin has relatively thin legs and therefore does not have to lift so much leg weight when running long distances.[73]

See also

- Kalenjin languages

Notes

^ [Ethnologue]

^ ab Census: Here are the numbers. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

^ ab Ehret, Christopher. An African Classical Age: Eastern & Southern Africa in World History 1000 B.C. to A.D.400. University of Virginia, 1998, p.7

^ Clark, J., & Brandt, St, From Hunters to Farmers: The Causes and Consequences of Food Production in Africa. University of California Press, 1984, p.234

^ Ehret, Christopher. An African Classical Age: Eastern & Southern Africa in World History 1000 B.C. to A.D.400. University of Virginia, 1998, p.161-164

^ Ehret, C., History and the Testimony of Language, p.118[online]

^ Lane, Paul J. (2013-07-04). "The Archaeology of Pastoralism and Stock-Keeping in East Africa". doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199569885.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199569885-e-40..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Ehret, C., History and the Testimony of Language, p.118

^ Goldstein, S., Quantifying endscraper reduction in the context of obsidian exchange among early pastoralists in southwestern Kenya, 2014, W.S.Mney & Son, p.5

^ Robertshaw, P., The Elmenteitan; an early food producing culture in East Africa, Taylor & Francis, p.57[online]

^ Ehret, C., and Posnansky M., The Archaeological and Linguistic Reconstruction of African History, University of California, 1982 [online]

^ Sirikwa and Engaruka: Dairy Farming, Irrigation [online]

^ Kyule, David M., 1989, Economy and subsistence of iron age Sirikwa Culture at Hyrax Hill, Nakuru: a zooarcheaological approach p.211

^ The Technological and Socio-Economic Organization of the Elmenteitan Early Herders in Southern Kenya (3000-1200 BP), Goldstein, S.T., Washington University in Saint Louis, p.35-36

^ Kyule, David M., 1989, Economy and subsistence of iron age Sirikwa Culture at Hyrax Hill, Nakuru: a zooarcheaological approach p.211

^ ab Spear, T. and Waller, R. Being Maasai: Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa. James Currey Publishers, 1993, p. 44-46 (online)

^ Hollis A.C, The Nandi – Their Language and Folklore. The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1909, p. xvii

^ Spear, T. and Waller, R. Being Maasai: Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa. James Currey Publishers, 1993, p. 42 (online)

^ Pavitt, N. Kenya: The First Explorers,Aurum Press, 1989, p. 107

^ Katsuyoshi, F., & Markakis, J., Ethnicity & Conflict in the Horn of Africa, p.67-68[online]

^ Trillo, R., The Rough Guide to Kenya, Rough Guides p.636

^ Spear, T. and Waller, R. Being Maasai: Ethnicity & Identity in East Africa. James Currey Publishers, 1993, p. 47 (online)

^ Nandi and Other Kalenjin Peoples – History and Cultural Relations, Countries and Their Cultures. Everyculture.com forum. Accessed 19 August 2014

^ Chesaina, C. Oral Literature of the Kalenjin. Heinmann Kenya Ltd, 1991, p. 2

^ Ehret, Christopher. An African Classical Age: Eastern & Southern Africa in World History 1000 B.C. to A.D.400. University of Virginia, 1998, p.178

^ Pavitt, N. Kenya: The First Explorers,Aurum Press, 1989, p. 121

^ Nandi Resistance to British Rule 1890–1906. By A. T. Matson. Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1972. Pp. vii+391

^ cf. Evans-Pritchard 1965.

^ Countries & their Cultures; Kalenjin online

^ Chesang, W. The Standard Moi and the Kalenjin: Just who owes who what? August 12, 2016

^ Kalenjin Tribe, People, Language, Culture and Traditions - Kalenjin Religion & Expressive Culture[online]

^ Kalenjin Tribe, People, Language, Culture and Traditions - Food[online]

^ Countries & their Cultures, Kalenjin online

^ Countries and their Cultures[online]

^ DP Ruto shocks Baringo farmers after buying 1,000 goats for Sh12 million cash[online]

^ Countries and their Cultures[online]

^ Kenya: What does the Kip prefix in many Kenyan names mean?[online]

^ Common Kalenjin names and their meaning[online]

^ Kalenjin Names for Boys and Girls[online]

^ Understanding Kalenjin Initiation Rites[online]

^ Kenya: What does the Kip prefix in many Kenyan names mean?[online]

^ One of The Nandis’ Oldest Ritual of All Time[online]

^ Understanding Kalenjin Initiation Rites[online]

^ Is the Kalenjin’s age-old tradition under trial at the International Criminal Court?[online]

^ Over 70 girls in Nandi County graduate from special training [online]

^ Dowry and wedding on same day[online]

^ Interesting steps in traditional marriage ceremony amongst the Kalenjin community[online]

^ Interesting steps in traditional marriage ceremony amongst the Kalenjin community[online]

^ Traditional Koito wedding[online]

^ The Fusion of Culture[online]

^ Dowry and wedding on same day[online]

^ Interesting steps in traditional marriage ceremony amongst the Kalenjin community[online]

^ Kalenjin Tribe, People, Language, Culture and Traditions - Kalenjin Religion & Expressive Culture[online]

^ Respect title deeds, elders tell State[online]

^ Show of unity: Kalenjin, Gema elders pay Sh300,000 for sick Luo colleague[online]

^ Kipchumba, P., Oral Literature of the Marakwet of Kenya, Nairobi: Kipchumba Foundation

ISBN 978-1-9731-6006-9

ISBN 1-9731-6006-4 [1]

^ Chesaina, C. Oral Literature of the Kalenjin. Heinmann Kenya Ltd, 1991, p. 39

^ Araap Sambu, K., The Misiri Legend Explored: A Linguistic Inquiry into the Kalenjiin Peopleís Oral Tradition of Ancient Egyptian Origin, p.38[online]

^ The writer I knew: Remembering Benjamin Kipkorir, Nation online

^ Benjamin Kipkorir, the reluctant academic, Standard online

^ Cianrunji Chesaina, online

^ The King of Kalenjin gospel, Daily Nation

^ 10 Best Kalenjin Musicians: Sweetstar, Msupa S, Chelelel and Junior Kotestes top in the list, Jambo News

^ Kenya & France Collaborate In New Jam ‘ Mbali Na Mimi’, 64Hiphop

^ 10 Best Kalenjin Musicians: Sweetstar, Msupa S, Chelelel and Junior Kotestes top in the list, Jambo News

^ Kipkore, W., et al, A study of the medicinal plants used by the Marakwet Community in Kenya[online]

^ Kigen, G., et al, Ethnomedicinal Plants Traditionally Used by the Keiyo Community in Elgeyo Marakwet County, Kenya[online]

^ Olingo, A. The rise, fall and rise again of Rivatex, firm that now holds patent for Tami dye, March 10, 2016

^ Impact of Imporved Livestock Disease Control on Household Diet and Welfare: a study in Uasin Gishu District, Kenya, ILRAD, 1992 [online]

^ Kalenjin Tribe, People, Language, Culture and Traditions - Food[online]

^ ab Why Kenyans Make Such Great Runners: A Story of Genes and Cultures, Atlantic online

^ Million Dollar Legs,The Guardian online

^ Running Circles around Us: East African Olympians’ Advantage May Be More Than Physical, Scientific American online

Bibliography

- Evans-Pritchard, E.E. (1965) 'The political structure of the Nandi-speaking peoples of Kenya', in The position of women in primitive societies and other essays in social anthropology, pp. 59–75.

- Entine, Jon. (2000) 'The Kenya Connection', in TABOO: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports And Why We're Afraid to Talk About It. https://web.archive.org/web/20081209004844/http://www.jonentine.com/reviews/quokka_03.htm

- Kipchumba Foundation (2017) Aspects of Indigenous Religion among the Marakwet of Kenya, Nairobi: Kipchumba Foundation,

ISBN 978-1-9732-0939-3

ISBN 1-9732-0939-X [2]

- Omosule, Monone (1989) 'Kalenjin: the emergence of a corporate name for the 'Nandi-speaking tribes' of East Africa', Genève-Afrique, 27, 1, pp. 73–88.

- Sutton, J.E.G. (1978) 'The Kalenjin', in Ogot, B.A. (ed.) Kenya before 1900, pp. 21–52.

- Larsen, Henrik B. (2002) 'Why Are Kenyan Runners Superior?'

- Tanser, Toby (2008) More Fire. How to Run the Kenyan Way.

- Warner, Gregory (2013) 'How One Kenyan Tribe Produces The World's Best Runners'

External links

- Census: Here are the numbers

- Peering Under the Hood of Africa's Runners

- Biikabkutit

[3][permanent dead link]

- Cheptiret Online