Restless legs syndrome

| Restless legs syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Willis–Ekbom disease (WED),[1] Wittmaack–Ekbom syndrome |

| |

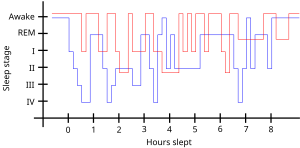

| Sleep pattern of a person with restless legs syndrome (red) versus a healthy sleep pattern (blue). | |

| Specialty | Sleep medicine |

| Symptoms | Unpleasant feeling in the legs that briefly improves with moving them[2] |

| Complications | Daytime sleepiness, low energy, irritability, depressed mood[2] |

| Usual onset | More common with older age[3] |

| Risk factors | Low iron levels, kidney failure, Parkinson's disease, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy, certain medications[2][4][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other possible causes[6] |

| Treatment | Lifestyle changes, medication[2] |

| Medication | Levodopa, dopamine agonists, gabapentin[4] |

| Frequency | 2.5–15% (US)[4] |

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a disorder that causes a strong urge to move one's legs.[2] There is often an unpleasant feeling in the legs that improves somewhat with moving them.[2] This is often described as aching, tingling, or crawling in nature.[2] Occasionally the arms may also be affected.[2] The feelings generally happen when at rest and therefore can make it hard to sleep.[2] Due to the disturbance in sleep, people with RLS may have daytime sleepiness, low energy, irritability, and a depressed mood.[2] Additionally, many have limb twitching during sleep.[7]

Risk factors for RLS include low iron levels, kidney failure, Parkinson's disease, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, and pregnancy.[2][4] A number of medications may also trigger the disorder including antidepressants, antipsychotics, antihistamines, and calcium channel blockers.[5] There are two main types.[2] One is early onset RLS which starts before age 45, runs in families and worsens over time.[2] The other is late onset RLS which begins after age 45, starts suddenly, and does not worsen.[2] Diagnosis is generally based on a person's symptoms after ruling out other potential causes.[6]

Restless leg syndrome may resolve if the underlying problem is addressed.[8] Otherwise treatment includes lifestyle changes and medication.[2] Lifestyle changes that may help include stopping alcohol and tobacco use, and sleep hygiene.[8] Medications used include levodopa or a dopamine agonist such as pramipexole.[4] RLS affects an estimated 2.5–15% of the American population.[4] Females are more commonly affected than males and it becomes more common with age.[3]

Contents

1 Signs and symptoms

1.1 Primary and secondary

2 Causes

2.1 ADHD

2.2 Medications

2.3 Genetics

3 Mechanism

4 Diagnosis

5 Differential diagnosis

6 Prevention

7 Treatment

7.1 Physical measures

7.2 Iron

7.3 Medications

8 Prognosis

9 Epidemiology

10 History

10.1 Nomenclature

11 Controversy

12 References

13 External links

Signs and symptoms

RLS sensations range from pain or an aching in the muscles, to "an itch you can't scratch", a "buzzing sensation", an unpleasant "tickle that won't stop", a "crawling" feeling, or limbs jerking while awake. The sensations typically begin or intensify during quiet wakefulness, such as when relaxing, reading, studying, or trying to sleep.[9]

It is a "spectrum" disease with some people experiencing only a minor annoyance and others having major disruption of sleep and impairments in quality of life.[10]

The sensations—and the need to move—may return immediately after ceasing movement or at a later time. RLS may start at any age, including childhood, and is a progressive disease for some, while the symptoms may remit in others.[11] In a survey among members of the Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation,[12] it was found that up to 45% of patients had their first symptoms before the age of 20 years.[13]

- "An urge to move, usually due to uncomfortable sensations that occur primarily in the legs, but occasionally in the arms or elsewhere."

- The sensations are unusual and unlike other common sensations. Those with RLS have a hard time describing them, using words or phrases such as uncomfortable, painful, 'antsy', electrical, creeping, itching, pins and needles, pulling, crawling, buzzing, and numbness. It is sometimes described similar to a limb 'falling asleep' or an exaggerated sense of positional awareness of the affected area. The sensation and the urge can occur in any body part; the most cited location is legs, followed by arms. Some people have little or no sensation, yet still, have a strong urge to move.

- "Motor restlessness, expressed as activity, which relieves the urge to move."

- Movement usually brings immediate relief, although temporary and partial. Walking is most common; however, stretching, yoga, biking, or other physical activity may relieve the symptoms. Continuous, fast up-and-down movements of the leg, and/or rapidly moving the legs toward then away from each other, may keep sensations at bay without having to walk. Specific movements may be unique to each person.

- "Worsening of symptoms by relaxation."

- Sitting or lying down (reading, plane ride, watching TV) can trigger the sensations and urge to move. Severity depends on the severity of the person's RLS, the degree of restfulness, duration of the inactivity, etc.

- "Variability over the course of the day-night cycle, with symptoms worse in the evening and early in the night."

- Some experience RLS only at bedtime, while others experience it throughout the day and night. Most people experience the worst symptoms in the evening and the least in the morning.

- "Restless legs feel similar to the urge to yawn, situated in the legs or arms."

- These symptoms of RLS can make sleeping difficult for many patients and a recent poll shows the presence of significant daytime difficulties resulting from this condition. These problems range from being late for work to missing work or events because of drowsiness. Patients with RLS who responded reported driving while drowsy more than patients without RLS. These daytime difficulties can translate into safety, social and economic issues for the patient and for society.

Individuals with RLS have higher rates of depression and anxiety disorders.[14]

Primary and secondary

RLS is categorized as either primary or secondary.

- Primary RLS is considered idiopathic or with no known cause. Primary RLS usually begins slowly, before approximately 40–45 years of age and may disappear for months or even years. It is often progressive and gets worse with age. RLS in children is often misdiagnosed as growing pains.

- Secondary RLS often has a sudden onset after age 40, and may be daily from the beginning. It is most associated with specific medical conditions or the use of certain drugs (see below).

Causes

RLS is often due to iron deficiency (low total body iron status) and this accounts for 20% of cases.[15] A study published in 2007 noted that RLS features were observed in 34% of people having iron deficiency as against 6% of controls.[16]

Other associated conditions include varicose vein or venous reflux, folate deficiency, magnesium deficiency, fibromyalgia, sleep apnea, uremia, diabetes, thyroid disease, peripheral neuropathy, Parkinson's disease, POTS, and certain autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren's syndrome, celiac disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. RLS can also worsen in pregnancy.[17] In a 2007 study, RLS was detected in 36% of people attending a phlebology (vein disease) clinic, compared to 18% in a control group.[18]

ADHD

An association has been observed between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and RLS or periodic limb movement disorder.[19] Both conditions appear to have links to dysfunctions related to the neurotransmitter dopamine, and common medications for both conditions among other systems, affect dopamine levels in the brain.[20] A 2005 study suggested that up to 44% of people with ADHD had comorbid (i.e. coexisting) RLS, and up to 26% of people with RLS had confirmed ADHD or symptoms of the condition.[21]

Medications

Certain medications may cause or worsen RLS, or cause it secondarily, including:

- Certain antiemetics (antidopaminergic ones)[22]

- Certain antihistamines (especially the sedating, first generation H1 antihistamines often in over-the-counter cold medications)[22]

- many antidepressants (both older TCAs and newer SSRIs)[22][23]

antipsychotics and certain anticonvulsants.[citation needed]

- a rebound effect of sedative-hypnotic drugs such as a benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome from discontinuing benzodiazepine tranquillizers or sleeping pills.[24]

alcohol withdrawal can also cause restless legs syndrome and other movement disorders such as akathisia and parkinsonism usually associated with antipsychotics[25]

opioid withdrawal is associated with causing and worsening RLS.[26]

Both primary and secondary RLS can be worsened by surgery of any kind; however, back surgery or injury can be associated with causing RLS.[27]

The cause vs. effect of certain conditions and behaviors observed in some patients (ex. excess weight, lack of exercise, depression or other mental illnesses) is not well established. Loss of sleep due to RLS could cause the conditions, or medication used to treat a condition could cause RLS.[28][29]

Genetics

More than 60% of cases of RLS are familial and are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with variable penetrance.[30]

Research and brain autopsies have implicated both dopaminergic system and iron insufficiency in the substantia nigra.[31] Iron is well understood to be an essential co-factor for the formation of L-dopa, the precursor of dopamine.

Six genetic loci found by linkage are known and listed below. Other than the first one, all of the linkage loci were discovered using an autosomal dominant model of inheritance.

- The first genetic locus was discovered in one large French Canadian family and maps on chromosome 12q.[32][33] This locus was discovered using an autosomal recessive inheritance model. Evidence for this locus was also found using a transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) in 12 Bavarian families.[34]

- The second RLS locus maps to chromosome 14q and was discovered in one Italian family.[35] Evidence for this locus was found in one French Canadian family.[36] Also, an association study in a large sample 159 trios of European descent showed some evidence for this locus.[37]

- This locus maps to chromosome 9p and was discovered in two unrelated American families.[38] Evidence for this locus was also found by the TDT in a large Bavarian family,[39] in which significant linkage to this locus was found.[40]

- This locus maps to chromosome 20p and was discovered in a large French Canadian family with RLS.[41]

- This locus maps to chromosome 2p and was found in three related families from population isolated in South Tyrol.[42]

- The sixth locus is located on chromosome 16p12.1 and was discovered by Levchenko et al. in 2008.[43]

Three genes, MEIS1, BTBD9 and MAP2K5, were found to be associated to RLS.[44]

Their role in RLS pathogenesis is still unclear. More recently, a fourth gene, PTPRD was found to be associated to RLS[45]

There is also some evidence that periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) are associated with BTBD9 on chromosome 6p21.2,[46][47]MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD.[47] The presence of a positive family history suggests that there may be a genetic involvement in the etiology of RLS.

Mechanism

Most research on the disease mechanism of restless legs syndrome has focused on the dopamine and iron system.[48][49] These hypotheses are based on the observation that iron and levodopa, a prodrug of dopamine that can cross the blood–brain barrier and is metabolized in the brain into dopamine (as well as other mono-amine neurotransmitters of the catecholamine class) can be used to treat RLS, levodopa being a medicine for treating hypodopaminergic (low dopamine) conditions such as Parkinson's disease, and also on findings from functional brain imaging (such as positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging), autopsy series and animal experiments.[50] Differences in dopamine- and iron-related markers have also been demonstrated in the cerebrospinal fluid of individuals with RLS.[51] A connection between these two systems is demonstrated by the finding of low iron levels in the substantia nigra of RLS patients, although other areas may also be involved.[52]

Diagnosis

There are no specific tests for RLS, but non-specific laboratory tests are used to rule out other causes such as vitamin deficiencies. According to the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, four symptoms are used to confirm the diagnosis:[53]

- A strong urge to move the limbs, usually associated with unpleasant or uncomfortable sensations.

- It starts or worsens during inactivity or rest.

- It improves or disappears (at least temporarily) with activity.

- It worsens in the evening or night.

- These symptoms are not caused by any medical or behavioral condition.

Differential diagnosis

Other conditions that can produce similar symptoms include: akathisia[54] and nocturnal leg cramps.[55]

Peripheral artery disease and arthritis can also cause leg pain but this usually gets worse with movement.[7]

Prevention

Other than preventing the underlying causes, generally no method of preventing RLS has been established or studied. If RLS is due to specific treatable causes (specific medications or treatable conditions), then treatment of those causes may also remove or reduce RLS. Otherwise, medical responses focus on treating the condition, either symptomatically or by targeting lifestyle changes and bodily processes capable of modifying its expression or severity.[citation needed]

Treatment

Treatment of restless legs syndrome involves identifying the cause of symptoms when possible. The treatment process is designed to reduce symptoms, including decreasing the number of nights with RLS symptoms, the severity of RLS symptoms and nighttime awakenings. Improving the quality of life is another goal in treatment. This means improving overall quality of life, decreasing daytime sleepiness, and improving the quality of sleep. Pharmacologic treatment involves dopamine agonists or gabapentin enacarbil as first line drugs for daily restless legs syndrome, and opioids for treatment of resistant cases.[56] RLS drug therapy is not curative and has side effects such as nausea, dizziness, hallucinations, orthostatic hypotension, or daytime sleep attacks. An algorithm created by Mayo Clinic researchers provides guidance to the treating physician and patient, including non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatments.[57]

Treatment of RLS should not be considered until possible medical causes are ruled out, especially venous disorders. Secondary RLS may be cured if precipitating medical conditions (anemia, venous disorder) are managed effectively. Secondary conditions causing RLS include iron deficiency, varicose veins, and thyroid problems.

Physical measures

Stretching the leg muscles can bring temporary relief.[9][58] Walking and moving the legs, as the name "restless legs" implies, brings temporary relief. In fact, those with RLS often have an almost uncontrollable need to walk and therefore relieve the symptoms while they are moving. Unfortunately, the symptoms usually return immediately after the moving and walking ceases. A vibratory counter-stimulation device has been found to help some people with primary RLS to improve their sleep.[59]

Non-drug treatments include leg massages, hot baths, heating pads or ice packs applied to the legs, good sleep habits and a vibratory pad at night.[60]

Iron

According to some guidelines, all people with RLS should have their serum ferritin level tested.[57][61] The ferritin level, a measure of the body's iron stores, should be at least 50 µg/L (or ng/mL, an equivalent unit) for those with RLS. Oral iron supplements can increase ferritin levels. For some people, increasing ferritin will eliminate or reduce RLS symptoms; a ferritin level of 50 µg/L is not sufficient for some and increasing the level to 80 µg/L may further reduce symptoms. However, at least 40% of people will not notice any improvement. It is not advised to take oral iron supplements without first having ferritin levels tested, as many people with RLS do not have low ferritin and taking iron when it is not called for is unlikely to offer any therapeutic benefit whilst still able to cause adverse events. All parenteral iron treatments require diagnosis with laboratory tests to avoid iron overload.

Medications

For those whose RLS disrupts or prevents sleep or regular daily activities, medication may be useful. Evidence supports the use of dopamine agonists including: pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine, and cabergoline.[62][63] They reduce symptoms, improve sleep quality and quality of life.[64]Levodopa is also effective.[65] One review found pramipexole to be better than ropinirole.[66]

There are, however, issues with the use of dopamine agonists including augmentation. This is a medical condition where the drug itself causes symptoms to increase in severity and/or occur earlier in the day. Dopamine agonists may also cause rebound when symptoms increase as the drug wears off. In many cases, the longer dopamine agonists have been used the higher the risk of augmentation and rebound as well as the severity of the symptoms. Also, a recent study indicated that dopamine agonists used in restless leg syndrome can lead to an increase in compulsive gambling.[67]

Gabapentin or pregabalin, a non-dopaminergic treatment for moderate to severe primary RLS[68]

Opioids are only indicated in severe cases that do not respond to other measures due to their high rate of side effects.[69]

Benzodiazepines, such as diazepam or clonazepam, are not generally recommended,[70] and their effectiveness is unknown.[71] They however are sometimes still used as a second line,[72] as add on agents.[71]Quinine is not recommended due to its risk of serious side effects involving the blood.[73]

Prognosis

RLS symptoms may gradually worsen with age,[74] though more slowly for those with the idiopathic form of RLS than for patients who also have associated medical condition. Nevertheless, current therapies can control the disorder, minimizing symptoms and increasing periods of restful sleep. In addition, some patients have remissions, periods in which symptoms decrease or disappear for days, weeks, or months, although symptoms usually eventually reappear. Being diagnosed with RLS does not indicate or foreshadow another neurological disease.

Epidemiology

RLS affects an estimated 2.5–15% of the American population.[4][75] A minority (around 2.7% of the population) experience daily or severe symptoms.[76] RLS is twice as common in women as in men,[77] and Caucasians are more prone to RLS than people of African descent.[75] RLS occurs in 3% of individuals from the Mediterranean or Middle Eastern region, and in 1–5% of those from the Far East, indicating that different genetic or environmental factors, including diet, may play a role in the prevalence of this syndrome.[75][78]

With age, RLS becomes more common, and RLS diagnosed at an older age runs a more severe course.[58]

RLS is even more common in individuals with iron deficiency, pregnancy, or end-stage kidney disease.[79][80] Poor general health is also linked.[81]

Neurologic conditions linked to RLS include Parkinson's disease, spinal cerebellar atrophy, spinal stenosis,[specify] lumbosacral radiculopathy and Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 2.[75] Approximately 80–90% of people with RLS also have periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), which causes slow "jerks" or flexions of the affected body part. These occur during sleep (PLMS = periodic limb movement while sleeping) or while awake (PLMW—periodic limb movement while waking).

The National Sleep Foundation's 1998 Sleep in America poll showed that up to 25 percent of pregnant women developed RLS during the third trimester.[82]

History

The first known medical description of RLS was by Sir Thomas Willis in 1672.[83] Willis emphasized the sleep disruption and limb movements experienced by people with RLS. Initially published in Latin (De Anima Brutorum, 1672) but later translated to English (The London Practice of Physick, 1685), Willis wrote:

| “ | Wherefore to some, when being abed they betake themselves to sleep, presently in the arms and legs, leapings and contractions on the tendons, and so great a restlessness and tossings of other members ensue, that the diseased are no more able to sleep, than if they were in a place of the greatest torture. | ” |

The term "fidgets in the legs" has also been used as early as the early nineteenth century.[84]

Subsequently, other descriptions of RLS were published, including those by Francois Boissier de Sauvages (1763), Magnus Huss (1849), Theodur Wittmaack (1861), George Miller Beard (1880), Georges Gilles de la Tourette (1898), Hermann Oppenheim (1923) and Frederick Gerard Allison (1943).[83][85] However, it was not until almost three centuries after Willis, in 1945, that Karl-Axel Ekbom (1907–1977) provided a detailed and comprehensive report of this condition in his doctoral thesis, Restless legs: clinical study of hitherto overlooked disease.[86] Ekbom coined the term "restless legs" and continued work on this disorder throughout his career. He described the essential diagnostic symptoms, differential diagnosis from other conditions, prevalence, relation to anemia, and common occurrence during pregnancy.[87][88]

Ekbom's work was largely ignored until it was rediscovered by Arthur S. Walters and Wayne A. Hening in the 1980s. Subsequent landmark publications include 1995 and 2003 papers, which revised and updated the diagnostic criteria.[9][89]Journal of Parkinsonism and RLS is the first peer-reviewed, online, open access journal dedicated to publishing research about Parkinson's disease and was founded by a Canadian neurologist Dr. Abdul Qayyum Rana.

Nomenclature

For decades the most widely used name for the disease was restless legs syndrome, and it is still the most commonly used. In 2013 the Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation renamed itself the Willis–Ekbom Disease Foundation,[1] and it encourages the use of the name Willis–Ekbom disease; its reasons are quoted as follows:[1]

| “ | The name Willis–Ekbom disease:

| ” |

A point of confusion is that RLS and delusional parasitosis are entirely different conditions that have both been called "Ekbom syndrome", as both syndromes were described by the same person, Karl-Axel Ekbom.[90] Today, calling WED/RLS "Ekbom syndrome" is outdated usage, as the unambiguous names (WED or RLS) are preferred for clarity.

Controversy

Some doctors express the view that the incidence of restless leg syndrome is exaggerated by manufacturers of drugs used to treat it.[91] Others believe it is an underrecognized and undertreated disorder.[75] Further, GlaxoSmithKline ran advertisements that, while not promoting off-license use of their drug (ropinirole) for treatment of RLS, did link to the Ekbom Support Group website. That website contained statements advocating the use of ropinirole to treat RLS. The ABPI ruled against GSK in this case.[92]

References

^ abcd "Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation is now the Willis–Ekbom Disease Foundation". 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-09-15..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcdefghijklmno "What Is Restless Legs Syndrome?". NHLBI. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

^ ab "Who Is at Risk for Restless Legs Syndrome?". NHLBI. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

^ abcdefg Ramar, K; Olson, EJ (Aug 15, 2013). "Management of common sleep disorders". American Family Physician. 88 (4): 231–8. PMID 23944726.

^ ab "What Causes Restless Legs Syndrome?". NHLBI. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

^ ab "How Is Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosed?". NHLBI. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

^ ab "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Restless Legs Syndrome?". NHLBI. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

^ ab "How Is Restless Legs Syndrome Treated?". NHLBI. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

^ abc Allen, R; Picchietti, D; Hening, WA; Trenkwalder, C; Walters, AS; Montplaisi, J; Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis Epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health; International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (2003). "Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health". Sleep Medicine. 4 (2): 101–19. doi:10.1016/S1389-9457(03)00010-8. PMID 14592341.

^ Earley, Christopher J.; Silber, Michael H. (2010). "Restless legs syndrome: Understanding its consequences and the need for better treatment". Sleep Medicine. 11 (9): 807–15. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2010.07.007. PMID 20817595.

^ Xiong, L.; Montplaisir, J.; Desautels, A.; Barhdadi, A.; Turecki, G.; Levchenko, A.; Thibodeau, P.; Dubé, M. P.; Gaspar, C.; Rouleau, GA (2010). "Family Study of Restless Legs Syndrome in Quebec, Canada: Clinical Characterization of 671 Familial Cases". Archives of Neurology. 67 (5): 617–22. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.67. PMID 20457962.

^ "Willis–Ekbom Disease Foundation Reverts to Original Name" (PDF). 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24.

^ Walters, A. S.; Hickey, K.; Maltzman, J.; Verrico, T.; Joseph, D.; Hening, W.; Wilson, V.; Chokroverty, S. (1996). "A questionnaire study of 138 patients with restless legs syndrome: The 'Night-Walkers' survey". Neurology. 46 (1): 92–5. doi:10.1212/WNL.46.1.92. PMID 8559428.

^ Becker, PM; Sharon, D (July 2014). "Mood disorders in restless legs syndrome (Willis–Ekbom disease)". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 75 (7): e679–94. doi:10.4088/jcp.13r08692. PMID 25093484.

^ "Restless legs syndrome: detection and management in primary care. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group on Restless Legs Syndrome". American Family Physician. 62 (1): 108–14. 2000. PMID 10905782.

^ Rangarajan, Sunad; d'Souza, George Albert (2007). "Restless legs syndrome in Indian patients having iron deficiency anemia in a tertiary care hospital". Sleep Medicine. 8 (3): 247–51. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2006.10.004. PMID 17368978.

^ Pantaleo, Nicholas P.; Hening, Wayne A.; Allen, Richard P.; Earley, Christopher J. (2010). "Pregnancy accounts for most of the gender difference in prevalence of familial RLS". Sleep Medicine. 11 (3): 310–313. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2009.04.005. PMC 2830334. PMID 19592302.

^ McDonagh, B; King, T; Guptan, R C (2007). "Restless legs syndrome in patients with chronic venous disorders: an untold story". Phlebology. 22 (4): 156–63. doi:10.1258/026835507781477145. PMID 18265529.

^ Walters, A. S.; Silvestri, R; Zucconi, M; Chandrashekariah, R; Konofal, E (2008). "Review of the Possible Relationship and Hypothetical Links Between Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and the Simple Sleep Related Movement Disorders, Parasomnias, Hypersomnias, and Circadian Rhythm Disorders". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 4 (6): 591–600. PMC 2603539. PMID 19110891.

^ Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder – Other Disorders Associated with ADHD Archived 2008-05-07 at the Wayback Machine., University of Maryland Medical Center.

^ Cortese, S; Konofal, E; Lecendreux, M; Arnulf, I; Mouren, MC; Darra, F; Dalla Bernardina, B (2005). "Restless legs syndrome and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A review of the literature". Sleep. 28 (8): 1007–13. PMID 16218085.

^ abc Buchfuhrer, MJ (October 2012). "Strategies for the treatment of restless legs syndrome". Neurotherapeutics (Review). 9 (4): 776–90. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0139-4. PMC 3480566. PMID 22923001.

^ Rottach, K; Schaner, B; Kirch, M; Zivotofsky, A; Teufel, L; Gallwitz, T; Messer, T (2008). "Restless legs syndrome as side effect of second generation antidepressants". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 43 (1): 70–5. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.02.006. PMID 18468624.

^ Ashton, H (1991). "Protracted withdrawal syndromes from benzodiazepines". Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 8 (1–2): 19–28. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(91)90023-4. PMID 1675688.

^ Neiman, J; Lang, AE; Fornazzari, L; Carlen, PL (May 1990). "Movement disorders in alcoholism: a review". Neurology. 40 (5): 741–6. doi:10.1212/wnl.40.5.741. PMID 2098000.

^ Cohrs, S; Rodenbeck, A; Hornyak, M; Kunz, D (November 2008). "[Restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements, and psychopharmacology]". Der Nervenarzt. 79 (11): 1263–4, 1266–72. doi:10.1007/s00115-008-2575-2. PMID 18958441.

^ Crotti, Francesco Maria; Carai, A.; Carai, M.; Sgaramella, E.; Sias, W. (2005). "Entrapment of crural branches of the common peroneal nerve". Advanced Peripheral Nerve Surgery and Minimal Invasive Spinal Surgery. Acta Neurochirurgica. 97. pp. 69–70. doi:10.1007/3-211-27458-8_15. ISBN 3-211-23368-7.

^ "Exercise and Restless Legs Syndrome". Archived from the original on 2015-08-06. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

^ Phillips, Barbara A.; Britz, Pat; Hening, Wayne (October 31, 2005). The NSF 2005 Sleep in American poll and those at risk for RLS. Chest 2005. Lay summary – ScienceDaily (October 31, 2005).

^ Lavigne, GJ; Montplaisir, JY (1994). "Restless legs syndrome and sleep bruxism: prevalence and association among Canadians". Sleep. 17 (8): 739–43. PMID 7701186.

^ Connor, J.R.; Boyer, P.J.; Menzies, S.L.; Dellinger, B.; Allen, R.P.; Ondo, W.G.; Earley, C.J. (2003). "Neuropathological examination suggests impaired brain iron acquisition in restless legs syndrome". Neurology. 61 (3): 304–9. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000078887.16593.12. PMID 12913188.

^ Desautels, Alex; Turecki, Gustavo; Montplaisir, Jacques; Sequeira, Adolfo; Verner, Andrei; Rouleau, Guy A. (2001). "Identification of a Major Susceptibility Locus for Restless Legs Syndrome on Chromosome 12q". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (6): 1266–70. doi:10.1086/324649.

^ Desautels, A.; Turecki, G; Montplaisir, J; Xiong, L; Walters, AS; Ehrenberg, BL; Brisebois, K; Desautels, AK; Gingras, Y; Johnson, WG; Lugaresi, E; Coccagna, G; Picchietti, DL; Lazzarini, A; Rouleau, GA (2005). "Restless Legs Syndrome: Confirmation of Linkage to Chromosome 12q, Genetic Heterogeneity, and Evidence of Complexity". Archives of Neurology. 62 (4): 591–6. doi:10.1001/archneur.62.4.591. PMID 15824258.

^ Winkelmann, Juliane; Lichtner, Peter; Pütz, Benno; Trenkwalder, Claudia; Hauk, Stephanie; Meitinger, Thomas; Strom, Tim; Muller-Myhsok, Bertram (2006). "Evidence for further genetic locus heterogeneity and confirmation of RLS-1 in restless legs syndrome". Movement Disorders. 21 (1): 28–33. doi:10.1002/mds.20627. PMID 16124010.

^ Bonati, M. T. (2003). "Autosomal dominant restless legs syndrome maps on chromosome 14q". Brain. 126 (6): 1485–92. doi:10.1093/brain/awg137.

^ Levchenko, Anastasia; Montplaisir, Jacques-Yves; Dubé, Marie-Pierre; Riviere, Jean-Baptiste; St-Onge, Judith; Turecki, Gustavo; Xiong, Lan; Thibodeau, Pascale; Desautels, Alex; Verlaan, Dominique J.; Rouleau, Guy A. (2004). "The 14q restless legs syndrome locus in the French Canadian population". Annals of Neurology. 55 (6): 887–91. doi:10.1002/ana.20140. PMID 15174026.

^ Kemlink, David; Polo, Olli; Montagna, Pasquale; Provini, Federica; Stiasny-Kolster, Karin; Oertel, Wolfgang; De Weerd, Al; Nevsimalova, Sona; Sonka, Karel; Högl, Birgit; Frauscher, Birgit; Poewe, Werner; Trenkwalder, Claudia; Pramstaller, Peter P.; Ferini-Strambi, Luigi; Zucconi, Marco; Konofal, Eric; Arnulf, Isabelle; Hadjigeorgiou, Georgios M.; Happe, Svenja; Klein, Christine; Hiller, Anja; Lichtner, Peter; Meitinger, Thomas; Müller-Myshok, Betram; Winkelmann, Juliane (2007). "Family-based association study of the restless legs syndrome loci 2 and 3 in a European population". Movement Disorders. 22 (2): 207–12. doi:10.1002/mds.21254. PMID 17133505.

^ Chen, Shenghan; Ondo, William G.; Rao, Shaoqi; Li, Lin; Chen, Qiuyun; Wang, Qing (2004). "Genomewide Linkage Scan Identifies a Novel Susceptibility Locus for Restless Legs Syndrome on Chromosome 9p". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 876–885. doi:10.1086/420772.

^ Liebetanz, K. M.; Winkelmann, J; Trenkwalder, C; Pütz, B; Dichgans, M; Gasser, T; Müller-Myhsok, B (2006). "RLS3: Fine-mapping of an autosomal dominant locus in a family with intrafamilial heterogeneity". Neurology. 67 (2): 320–321. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000224886.65213.b5. PMID 16864828.

^ Lohmann-Hedrich, K.; Neumann, A.; Kleensang, A.; Lohnau, T.; Muhle, H.; Djarmati, A.; König, I. R.; Pramstaller, P. P.; Schwinger, E.; Kramer, P. L.; Ziegler, A.; Stephani, U.; Klein, C. (2008). "Evidence for linkage of restless legs syndrome to chromosome 9p: Are there two distinct loci?". Neurology. 70 (9): 686–694. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000282760.07650.ba. PMID 18032746.

^ Levchenko, A.; Provost, S; Montplaisir, JY; Xiong, L; St-Onge, J; Thibodeau, P; Rivière, JB; Desautels, A; Turecki, G; Dubé, M. P.; Rouleau, G. A. (2006). "A novel autosomal dominant restless legs syndrome locus maps to chromosome 20p13". Neurology. 67 (5): 900–901. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000233991.20410.b6. PMID 16966564.

^ Pichler, Irene; Marroni, Fabio; Beu Volpato, Claudia; Gusella, James F.; Klein, Christine; Casari, Giorgio; De Grandi, Alessandro; Pramstaller, Peter P. (2006). "Linkage Analysis Identifies a Novel Locus for Restless Legs Syndrome on Chromosome 2q in a South Tyrolean Population Isolate". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 79 (4): 716–23. doi:10.1086/507875. PMC 1592574. PMID 16960808.

^ Levchenko, Anastasia; Montplaisir, Jacques-Yves; Asselin, GéRaldine; Provost, Sylvie; Girard, Simon L.; Xiong, Lan; Lemyre, Emmanuelle; St-Onge, Judith; Thibodeau, Pascale; Desautels, Alex; Turecki, Gustavo; Gaspar, Claudia; Dubé, Marie-Pierre; Rouleau, Guy A. (2009). "Autosomal-dominant locus for restless legs syndrome in French-Canadians on chromosome 16p12.1". Movement Disorders. 24 (1): 40–50. doi:10.1002/mds.22263. PMID 18946881.

^ Winkelmann, Juliane; Schormair, Barbara; Lichtner, Peter; Ripke, Stephan; Xiong, Lan; Jalilzadeh, Shapour; Fulda, Stephany; Pütz, Benno; Eckstein, Gertrud; Hauk, Stephanie; Trenkwalder, Claudia; Zimprich, Alexander; Stiasny-Kolster, Karin; Oertel, Wolfgang; Bachmann, Cornelius G; Paulus, Walter; Peglau, Ines; Eisensehr, Ilonka; Montplaisir, Jacques; Turecki, Gustavo; Rouleau, Guy; Gieger, Christian; Illig, Thomas; Wichmann, H-Erich; Holsboer, Florian; Müller-Myhsok, Bertram; Meitinger, Thomas (2007). "Genome-wide association study of restless legs syndrome identifies common variants in three genomic regions". Nature Genetics. 39 (8): 1000–6. doi:10.1038/ng2099. PMID 17637780.

^ Ding, Li; Getz, Gad; Wheeler, David A.; Mardis, Elaine R.; McLellan, Michael D.; Cibulskis, Kristian; Sougnez, Carrie; Greulich, Heidi; Muzny, Donna M.; Morgan, Margaret B.; Fulton, Lucinda; Fulton, Robert S.; Zhang, Qunyuan; Wendl, Michael C.; Lawrence, Michael S.; Larson, David E.; Chen, Ken; Dooling, David J.; Sabo, Aniko; Hawes, Alicia C.; Shen, Hua; Jhangiani, Shalini N.; Lewis, Lora R.; Hall, Otis; Zhu, Yiming; Mathew, Tittu; Ren, Yanru; Yao, Jiqiang; Scherer, Steven E.; Clerc, Kerstin (2008). "Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma". Nature. 455 (7216): 1069–75. doi:10.1038/nature07423. PMC 2694412. PMID 18948947.

^ Stefansson, Hreinn; Rye, David B.; Hicks, Andrew; Petursson, Hjorvar; Ingason, Andres; Thorgeirsson, Thorgeir E.; Palsson, Stefan; Sigmundsson, Thordur; Sigurdsson, Albert P.; Eiriksdottir, Ingibjorg; Soebech, Emilia; Bliwise, Donald; Beck, Joseph M.; Rosen, Ami; Waddy, Salina; Trotti, Lynn M.; Iranzo, Alex; Thambisetty, Madhav; Hardarson, Gudmundur A.; Kristjansson, Kristleifur; Gudmundsson, Larus J.; Thorsteinsdottir, Unnur; Kong, Augustine; Gulcher, Jeffrey R.; Gudbjartsson, Daniel; Stefansson, Kari (2007). "A Genetic Risk Factor for Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep". New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (7): 639–47. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072743. PMID 17634447.

^ ab Moore, H; Winkelmann, J; Lin, L; Finn, L; Peppard, P; Mignot, E (2014). "Periodic leg movements during sleep are associated with polymorphisms in BTBD9, TOX3/BC034767, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD". Sleep. 37 (9): 1535–1542. doi:10.5665/sleep.4006. PMC 4153066.

^ Allen, R (2004). "Dopamine and iron in the pathophysiology of restless legs syndrome (RLS)". Sleep Medicine. 5 (4): 385–91. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2004.01.012. PMID 15222997.

^ Clemens, S.; Rye, D; Hochman, S (2006). "Restless legs syndrome: Revisiting the dopamine hypothesis from the spinal cord perspective". Neurology. 67 (1): 125–130. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000223316.53428.c9. PMID 16832090.

^ Earley, C; b Barker, P; Horská, A; Allen, R (2006). "MRI-determined regional brain iron concentrations in early- and late-onset restless legs syndrome". Sleep Medicine. 7 (5): 458–61. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2005.11.009. PMID 16740411.

^ Allen, Richard P.; Connor, James R.; Hyland, Keith; Earley, Christopher J. (2009). "Abnormally increased CSF 3-Ortho-methyldopa (3-OMD) in untreated restless legs syndrome (RLS) patients indicates more severe disease and possibly abnormally increased dopamine synthesis". Sleep Medicine. 10 (1): 123–128. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.11.012. PMC 2655320. PMID 18226951.

^ Godau, Jana; Klose, Uwe; Di Santo, Adriana; Schweitzer, Katherine; Berg, Daniela (2008). "Multiregional brain iron deficiency in restless legs syndrome". Movement Disorders. 23 (8): 1184–1187. doi:10.1002/mds.22070. PMID 18442125.

^ "Restless Legs Syndrome Fact Sheet. How is restless legs syndrome diagnosed?". NIH. 2017-05-09.

^ Aggarwal, S; Dodd, S; Berk, M (2015). "Restless leg syndrome associated with atypical antipsychotics: Current status, pathophysiology, and clinical implications". Current Drug Safety. 10 (2): 98–105. doi:10.2174/1574886309666140527114159. PMID 24861990.

^ Rana, A. Q.; Khan, F; Mosabbir, A; Ondo, W (2014). "Differentiating nocturnal leg cramps and restless legs syndrome". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 14 (7): 813–8. doi:10.1586/14737175.2014.927734. PMID 24931546.

^ Karatas, Mehmet (2007). "Restless Legs Syndrome and Periodic Limb Movements During Sleep: Diagnosis and Treatment". The Neurologist. 13 (5): 294–301. doi:10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181422589. PMID 17848868.

^ ab Silber, Michael H.; Ehrenberg, Bruce L.; Allen, Richard P.; Buchfuhrer, Mark J.; Earley, Christopher J.; Hening, Wayne A.; Rye, David B.; Medical Advisory Board of the Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation (2004). "An Algorithm for the Management of Restless Legs Syndrome". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 79 (7): 916–22. doi:10.4065/79.7.916. PMID 15244390.

^ ab Allen, Richard P.; Earley, Christopher J. (2001). "Restless Legs Syndrome". Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 18 (2): 128–47. doi:10.1097/00004691-200103000-00004. PMID 11435804.

^ Foy, Jonette. "Regulation Name: Vibratory counter-stimulation device" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

^ "Restless Legs Syndrome". WebMD. Archived from the original on 29 August 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

^ Garcia-Borreguero, Diego; Stillman, Paul; Benes, Heike; Buschmann, Heiner; Chaudhuri, K Ray; Gonzalez Rodríguez, Victor M; Högl, Birgit; Kohnen, Ralf; Monti, Giorgio; Stiasny-Kolster, Karin; Trenkwalder, Claudia; Williams, Anne-Marie; Zucconi, Marco (2011). "Algorithms for the diagnosis and treatment of Willis–Ekbom Disease/restless legs syndrome in primary care". BMC Neurology. 11: 28. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-11-28. PMC 3056753. PMID 21352569.

^ Zintzaras, E; Kitsios, GD; Papathanasiou, AA; Konitsiotis, S; Miligkos, M; Rodopoulou, P; Hadjigeorgiou, GM (Feb 2010). "Randomized trials of dopamine agonists in restless legs syndrome: a systematic review, quality assessment, and meta-analysis". Clinical Therapeutics. 32 (2): 221–37. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.01.028. PMID 20206780.

^ Winkelman, JW; Armstrong, MJ; Allen, RP; Chaudhuri, KR; Ondo, W; Trenkwalder, C; Zee, PC; Gronseth, GS; Gloss, D; Zesiewicz, T (13 December 2016). "Practice guideline summary: Treatment of restless legs syndrome in adults: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 87 (24): 2585–2593. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000003388. PMC 5206998. PMID 27856776.

^ Scholz, H.; Trenkwalder, C.; Kohnen, R.; Riemann, D.; Kriston, L.; Hornyak, M. (2011). Hornyak, Magdolna, ed. "Dopamine agonists for restless legs syndrome". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD006009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006009.pub2. PMID 21412893.

^ Scholz, H; Trenkwalder, C; Kohnen, R; Riemann, D; Kriston, L; Hornyak, M (Feb 16, 2011). "Levodopa for restless legs syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 22 (2): CD005504. doi:10.7748/ns2008.09.22.52.62.p4194. PMID 21328278.

^ Quilici, S; Abrams, KR; Nicolas, A; Martin, M; Petit, C; Lleu, PL; Finnern, HW (Oct 2008). "Meta-analysis of the efficacy and tolerability of pramipexole versus ropinirole in the treatment of restless legs syndrome". Sleep medicine. 9 (7): 715–26. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.11.020. PMID 18226947.

^ Tippmann-Peikert, M.; Park, J. G.; Boeve, B. F.; Shepard, J. W.; Silber, M. H. (2007). "Pathologic gambling in patients with restless legs syndrome treated with dopaminergic agonists". Neurology. 68 (4): 301–3. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000252368.25106.b6. PMID 17242339. Lay summary – ScienceDaily (February 9, 2007).

^ Nagandla, K; De, S (July 2013). "Restless legs syndrome: pathophysiology and modern management". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 89 (1053): 402–10. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131634. PMID 23524988.

^ Wolkove, N.; Elkholy, O.; Baltzan, M.; Palayew, M. (2007). "Sleep and aging: 2. Management of sleep disorders in older people". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 176 (10): 1449–54. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070335. PMC 1863539. PMID 17485699.

^ Trenkwalder, C; Winkelmann, J; Inoue, Y; Paulus, W (August 2015). "Restless legs syndrome-current therapies and management of augmentation". Nature Reviews. Neurology. 11 (8): 434–45. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2015.122. PMID 26215616.

^ ab Carlos K, Prado GF, Teixeira CD, Conti C, de Oliveira MM, Prado LB, Carvalho LB (2017). "Benzodiazepines for restless legs syndrome". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3: CD006939. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006939.pub2. PMID 28319266.

^ Garcia-Borreguero, D; Stillman, P; Benes, H; Buschmann, H; Chaudhuri, KR; Gonzalez Rodríguez, VM; Högl, B; Kohnen, R; Monti, GC; Stiasny-Kolster, K; Trenkwalder, C; Williams, AM; Zucconi, M (27 February 2011). "Algorithms for the diagnosis and treatment of restless legs syndrome in primary care". BMC Neurology. 11: 28. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-11-28. PMC 3056753. PMID 21352569.

^ "Qualaquin (quinine sulfate): New Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy – Risk of serious hematological reactions". Archived from the original on 2010-07-16.

^ "Restless Legs Syndrome Factsheet". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

^ abcde Gamaldo, C. E.; Earley, C. J. (2006). "Restless Legs Syndrome: A Clinical Update". Chest. 130 (5): 1596–604. doi:10.1378/chest.130.5.1596. PMID 17099042.

^ Allen, R. P.; Walters, AS; Montplaisir, J; Hening, W; Myers, A; Bell, TJ; Ferini-Strambi, L (2005). "Restless Legs Syndrome Prevalence and Impact: REST General Population Study". Archives of Internal Medicine. 165 (11): 1286–92. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.11.1286. PMID 15956009.

^ Berger, K.; Luedemann, J; Trenkwalder, C; John, U; Kessler, C (2004). "Sex and the Risk of Restless Legs Syndrome in the General Population". Archives of Internal Medicine. 164 (2): 196–202. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.2.196. PMID 14744844.

^ "Welcome – National Sleep Foundation". Archived from the original on 2007-07-28. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

^ Lee, Kathryn A.; Zaffke, Mary Ellen; Baratte-Beebe, Kathleen (2001). "Restless Legs Syndrome and Sleep Disturbance during Pregnancy: The Role of Folate and Iron". Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine. 10 (4): 335–41. doi:10.1089/152460901750269652.

^ Merlino, G.; Piani, A.; Dolso, P.; Adorati, M.; Cancelli, I.; Valente, M.; Gigli, G. L. (2005). "Sleep disorders in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing dialysis therapy". Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 21: 184–90. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfi144.

^ Yeh, Paul; Walters, Arthur S.; Tsuang, John W. (1 December 2012). "Restless legs syndrome: a comprehensive overview on its epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment". Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung. 16 (4): 987–1007. doi:10.1007/s11325-011-0606-x. ISSN 1522-1709. PMID 22038683.

^ Sleep in America Poll Archived 2007-05-08 at the Wayback Machine.. National Sleep Foundation.

^ ab Coccagna, G; Vetrugno, R; Lombardi, C; Provini, F (2004). "Restless legs syndrome: an historical note". Sleep Medicine. 5 (3): 279–83. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2004.01.002. PMID 15165536.

^ Caleb Hillier PARRY (1815). Elements of Pathology and Therapeutics. Vol. 1 ... General Pathology. pp. 381 & 397. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

^ Konofal, Eric; Karroum, Elias; Montplaisir, Jacques; Derenne, Jean-Philippe; Arnulf, Isabelle (2009). "Two early descriptions of restless legs syndrome and periodic leg movements by Boissier de Sauvages (1763) and Gilles de la Tourette (1898)". Sleep Medicine. 10 (5): 586–91. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2008.04.008. PMID 18752999.

^ Ekrbom, Karl-Axel (2009). "PREFACE". Acta Medica Scandinavica. 121: 1–123. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1945.tb11970.x.

^ Teive, Hélio A.G.; Munhoz, Renato P.; Barbosa, Egberto Reis (2009). "Professor Karl-Axel Ekbom and restless legs syndrome". Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 15 (4): 254–7. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.07.011.

^ Ulfberg, J (2004). "The legacy of Karl-Axel Ekbom". Sleep Medicine. 5 (3): 223–4. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2004.04.002. PMID 15165526.

^ Walters, Arthur S.; Aldrich, Michael S.; Allen, Richard; Ancoli-Israel, Sonia; Buchholz, David; Chokroverty, Sudhansu; Coccagna, Giorgio; Earley, Christopher; Ehrenberg, Bruce; Feest, T. G.; Hening, Wayne; Kavey, Neil; Lavigne, Gilles; Lipinski, Joseph; Lugaresi, Elio; Montagna, Pasquale; Montplaisir, Jacques; Mosko, Sarah S.; Oertel, Wolfgang; Picchietti, Daniel; Pollmächer, Thomas; Shafor, Renata; Smith, Robert C.; Telstad, Wenche; Trenkwalder, Claudia; Von Scheele, Christian; Walters, Arthur S.; Ware, J. Catesby; Zucconi, Marco (1995). "Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome". Movement Disorders. 10 (5): 634–42. doi:10.1002/mds.870100517. PMID 8552117.

^ Wittmaack–Ekbom syndrome at Who Named It?

^ Woloshin, Steven; Schwartz, Lisa M. (2006). "Giving Legs to Restless Legs: A Case Study of How the Media Helps Make People Sick". PLoS Medicine. 3 (4): e170. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030170. PMC 1434499. PMID 16597175.

^ Templeton, Sarah-Kate (August 6, 2006). "Glaxo's cure for 'restless legs' was an unlicensed drug". Times Online. Times Newspapers Ltd. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

External links

| Classification | D

|

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Restless leg syndrome. |

Restless legs syndrome at Curlie

"National Institutes of Health: What is Restless Legs Syndrome?".

"Restless Legs Syndrome Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)".