Hawaiian religion

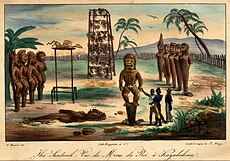

A depiction of a royal heiau (Hawaiian temple) at Kealakekua Bay, c. 1816

Hawaiian religion encompasses the indigenous religious beliefs and practices of the Native Hawaiians. It is polytheistic and animistic, with a belief in many deities and spirits, including the belief that spirits are found in non-human beings and objects such as animals, the waves, and the sky.

Hawaiian religion originated among the Tahitians and other Pacific islanders who landed in Hawaiʻi between 500 and 1300 AD.[1] Today, Hawaiian religious practices are protected by the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.[2] Traditional Hawaiian religion is unrelated to the modern New Age practice known as "Huna."[3][4]

Contents

1 Beliefs

1.1 Deities

1.2 Creation

1.3 Kahuna and Kapu

1.4 Prayer and heiau

2 History

2.1 Origins

2.2 Early Hawaiian religion

2.3 Contemporary

3 References

4 Further reading and resources

Beliefs

Deities

Kailua-Kona, Island of Hawaii

Hawaiian religion is polytheistic, with four deities most prominent: Kāne, Kū, Lono and Kanaloa.[5] Other notable deities include Laka, Kihawahine, Haumea, Papahānaumoku, and, most famously, Pele.[5] In addition, each family is considered to have one or more guardian spirits known as ʻaumakua that protected family.[5]

One breakdown of the Hawaiian pantheon[6] consists of the following groups:

- the four gods (ka hā) – Kū, Kāne, Lono, Kanaloa

- the forty male gods or aspects of Kāne (ke kanahā)

- the four hundred gods and goddesses (ka lau)

- the great multitude of gods and goddesses (ke kini akua)

- the spirits (na ʻunihipili)

- the guardians (na ʻaumākua)

Another breakdown[7] consists of three major groups:

- the four gods, or akua: Kū, Kāne, Lono, Kanaloa

- many lesser gods, or kupua, each associated with certain professions

- guardian spirits, ʻaumakua, associated with particular families

Creation

One Hawaiian creation myth is embodied in the Kumulipo, an epic chant linking the aliʻi, or Hawaiian royalty, to the gods. The Kumulipo is divided into two sections: night, or pō, and day, or ao, with the former corresponding to divinity and the latter corresponding to mankind. After the birth of Laʻilaʻi, the woman, and Kiʻi, the man, the man succeeds at seducing and reproducing with the woman before the god Kāne has a chance, thereby making the divine lineage of the gods younger than and thus subservient to the lineage of man. This, in turn, illustrates the transition of mankind from being symbols for the gods (the literal meaning of kiʻi) into the keeper of these symbols in the form of idols and the like.[8] The Kumulipo was recited during the time of Makahiki, to honor the god of fertility, Lono.[9]

Kahuna and Kapu

The kahuna were well respected, educated individuals that made up a social hierarchy class that served the King and the Courtiers and assisted the Maka'ainana (Common People). Selected to serve many practical and governmental purposes, Kahuna often were healers, navigators, builders, prophets/temple workers, and philosophers.

King Kamehameha II

They also talked with the spirits. Kahuna Kūpaʻiulu of Maui in 1867 described a counter-sorcery ritual to heal someone ill due to hoʻopiʻopiʻo, another’s evil thoughts. He said a kapa (cloth) was shaken. Prayers were said.

Then, "If the evil spirit suddenly appears (puoho) and possesses the patient, then he or she can be immediately saved by the conversation between the practitioner and that spirit."[10]

Pukui and others believed kahuna did not have mystical transcendent experiences as described in other religions. Although a person who was possessed (noho) would go into a trance-like state, it was not an ecstatic experience but simply a communion with the known spirits.[citation needed]

Kapu refers to a system of taboos designed to separate the spiritually pure from the potentially unclean. Thought to have arrived with Pāʻao, a priest or chief from Tahiti who arrived in Hawaiʻi sometime around 1200 AD,[11] the kapu imposed a series of restrictions on daily life. Prohibitions included:

- The separation of men and women during mealtimes (a restriction known as ʻaikapu)

- Restrictions on the gathering and preparation of food

- Women separated from the community during their menses

- Restrictions on looking at, touching, or being in close proximity with chiefs and individuals of known spiritual power

- Restrictions on overfishing

Hawaiian tradition shows that ʻAikapu was an idea led by the kahuna in order for Wākea, the sky father, to get alone with his daughter, Hoʻohokukalani without his wahine, or wife, Papa, the earth mother, noticing. The spiritually pure or laʻa, meaning "sacred" and unclean or haumia were to be separated. ʻAikapu included:

- The use of a different ovens to cook the food of male and female

- Different eating places

- Women were forbidden to eat pig, coconut, banana, and certain red foods because of their male symbolism.[12][13]

Hawaiian sacrifice, from Jacques Arago's account of Freycinet's travels around the world from 1817 to 1820.

- During times of war, the first two men to be killed were offered to the gods as sacrifices.[14]

Other Kapus included Mālama ʻĀina, meaning "caring of the land" and Niʻaupiʻo. Tradition says that mālama ʻāina originated from the first child of Wākea and Hoʻohokukalani being deformed so they buried him in the ground and what sprouted became the first kalo, also known as taro. The Hawaiian islands are all children of Papa, Wākea and Hoʻohokukalani so basically meaning that they are older siblings of the Hawaiian chiefs.[15] Second child of Wākea and Hoʻohokukalani became the first Aliʻi Nui, or "Grand Chief". This came to be called Niʻaupiʻo, the chiefly incest to create the "godly child".[16]

Punishments for breaking the kapu could include death, although if one could escape to a puʻuhonua, a city of refuge, one could be saved.[17] Kāhuna nui mandated long periods when the entire village must have absolute silence. No baby could cry, dog howl, or rooster crow, on pain of death.

Human sacrifice was not unknown.[18]

The kapu system remained in place until 1819 (see below).

Prayer and heiau

One side of Puʻukohola Heiau, a Hawaiian temple used as a place of worship and sacrifice.

Prayer was an essential part of Hawaiian life, employed when building a house, making a canoe, and giving lomilomi massage. Hawaiians addressed prayers to various gods depending on the situation. When healers picked herbs for medicine, they usually prayed to Kū and Hina, male and female, right and left, upright and supine. The people worshiped Lono during Makahiki season and Kū during times of war.[citation needed]

Histories from the 19th century describe prayer throughout the day, with specific prayers associated with mundane activities such as sleeping, eating, drinking, and traveling.[19][20] However, it has been suggested that the activity of prayer differed from the subservient styles of prayer often seen in the Western world:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

...the usual posture for prayer – sitting upright, head high and eyes open – suggests a relationship marked by respect and self-respect. The gods might be awesome, but the ʻaumākua bridged the gap between gods and man. The gods possessed great mana; but man, too, has some mana. None of this may have been true in the time of Pāʻao, but otherwise, the Hawaiian did not seem prostrate before his gods.[21]

Heiau, served as focal points for prayer in Hawaiʻi. Offerings, sacrifices, and prayers were offered at these temples, the thousands of koʻa (shrines), a multitude of wahi pana (sacred places), and at small kuahu (altars) in individual homes.

History

Origins

Although it is unclear when settlers first came to the Hawaiian Islands, there is significant evidence that the islands were settled no later than 800 AD and immigration continued to about 1300 AD.[22] Settlers came from the Marquesas, Tonga, Samoa, Easter Island, and greater Polynesia. At some point, a significant influx of Tahitian settlers landed on the Hawaiian islands, bringing with them their religious beliefs.

Early Hawaiian religion resembled other Polynesian religions in that it was largely focused on natural forces such as the tides, the sky, and volcanic activity as well as man's dependence on nature for subsistence. The major early gods reflected these characteristics, as the early Hawaiians worshiped Kāne (the god of the sky and creation), Kū (the god of war and male pursuits), Lono (the god of peace, rain, and fertility) and Kanaloa (the god of the ocean).

Early Hawaiian religion

As an indigenous culture, spread among eight islands, with waves of immigration over hundreds of years from various parts of the South Pacific, religious practices evolved over time and from place to place in different ways.

Hawaiian scholar Mary Kawena Pukui, who was raised in Kaʻū, Hawaii, maintained that the early Hawaiian gods were benign.[23] One Molokaʻi tradition follows this line of thought. Author and researcher Pali Jae Lee writes: "During these ancient times, the only 'religion' was one of family and oneness with all things. The people were in tune with nature, plants, trees, animals, the ‘āina, and each other. They respected all things and took care of all things. All was pono."[24]

"In the dominant current of Western thought there is a fundamental separation between humanity and divinity. ... In many other cultures, however, such differences between human and divine do not exist. Some peoples have no concept of a ‘Supreme Being’ or ‘Creator God’ who is by nature ‘other than’ his creation. They do, however, claim to experience a spirit world in which beings more powerful than they are concerned for them and can be called upon for help." [25]

"Along with ancestors and gods, spirits are part of the family of Hawaiians. "There are many kinds of spirits that help for good and many that aid in evil. Some lie and deceive, and some are truthful ... It is a wonderful thing how the spirits (ʻuhane) of the dead and the ‘angels’ (anela) of the ʻaumākua can possess living persons. Nothing is impossible to god-spirits, akua."[26]

Contemporary

Hula being performed during a ceremony at ʻIolani Palace where the Navy returned control of Kahoʻolawe to the State of Hawaiʻi.

Kamehameha the Great died in 1819. In the aftermath, two of his wives, Kaʻahumanu and Keōpūolani, then the two most powerful people in the kingdom, conferred with the kahuna nui, Hewahewa. They convinced young Liholiho, Kamehameha II, to overthrow the kapu system. They ordered the people to burn the wooden statues and tear down the rock temples.

Without the hierarchical system of religion in place, some abandoned the old gods, and others continued with cultural traditions of worshipping them, especially their family ʻaumākua.

Missionaries arrived in 1820, and most of the aliʻi converted to Christianity, including Kaʻahumanu and Keōpūolani, but it took 11 years for Kaʻahumanu to proclaim laws against ancient religious practices. "Worshipping of idols such as sticks, stones, sharks, dead bones, ancient gods and all untrue gods is prohibited. There is one God alone, Jehovah. He is the God to worship. The hula is forbidden, the chant (olioli), the song of pleasure (mele), foul speech, and bathing by women in public places. The planting of ʻawa is prohibited. Neither chiefs nor commoners are to drink ʻawa." (Kamakau, 1992, p. 298-301)

Offerings presented by Hawaiʻian religious practitioners at Ulupo Heiau, 2009

Although traditional Hawaiian religion was outlawed, a number of traditions typically associated with it survived by integration, practicing in hiding, or practicing in rural communities in the islands. Surviving traditions include the worship of family ancestral gods or ʻaumākua, veneration of iwi or bones, and preservation of sacred places or wahi pana. Hula was outlawed at one time as a religious practice but today is performed in both spiritual and secular contexts.

Traditional beliefs have also played a role in the politics of post-Contact Hawaiʻi. In the 1970s the Hawaiian religion experienced a resurgence during the Hawaiian Renaissance. In 1976, the members of a group "Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana" filed suit in federal court over the use of Kahoʻolawe by the United States Navy for target practice. Charging that the practice disturbed important cultural and religious sites Aluli et al. v. Brown forced the Navy to survey and protect important sites, perform conservation activities, and allow limited access to the island for religious purposes.[27] Similarly, outrage over the unearthing of 1,000 graves dating back to 850 AD during the construction of a Ritz-Carlton hotel on Maui in 1988 resulted in the redesign and relocation of the hotel inland as well as the appointment of the site as a state historic place.[28]

Along with the surviving traditions, some Hawaiians practice Christianized versions of old traditions. Others practice it as a co-religion.

In the 1930s, non-Hawaiian author Max Freedom Long created a philosophy and practice he called "Huna."[29] While Long and his successors have misrepresented this invention as a type of ancient, Hawaiian occultism,[29] it is actually a New Age product of cultural misappropriation and fantasy,[3][4] and not representative of traditional Hawaiian religion.[3][4]

References

^ Carroll, Bret (2000). The Routledge historical atlas of religion in America. Routledge. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-415-92131-7..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Cornell.edu. "AIRFA act 1978". Retrieved July 9, 2010.

^ abc Rothstein, Mikael, in Lewis, James R. and Daren Kemp. Handbook of New Age. Brill Academic Publishers, 2007

ISBN 978-90-04-15355-4

^ abc Chai, Makana Risser. "Huna, Max Freedom Long, and the Idealization of William Brigham," The Hawaiian Journal of History, Vol. 45 (2011) pp. 101-121

^ abc Luci Yamamoto; Amanda C. Gregg (2009). Lonely Planet Kauai. Lonely Planet. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-74104-136-1.

^ Gutmanis, June (1983). Na Pule Kahiko: Ancient Hawaiian Prayers. Editions Limited. pp. 4–14. ISBN 0-9607938-6-0.

^ Kauka, Jay. Religious Beliefs and Practices.

^ Valeri, Valerio (1985). Kingship and Sacrifice: Ritual and Society in Ancient Hawaii. Translated by Paula Wissing. University of Chicago Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 0-226-84560-5.

^ Beckwith, Martha Warren. "Lono of the Makahiki." The Kumulipo, a Hawaiian Creation Chant (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1951), 18.

^ Chun, Malcolm Naea; ʻAhahui Lāʻau Lapaʻau (1994). Must We Wait in Despair. First People's Productions. p. 179.

^ Pukui, Nana i ke Kumu: Look to the Source, Vol. II, 1972, p. 296

^ Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa, Native Land and Foreign Desires: Pehea Lā E Pono Ai? (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1992.),23

^ Malcolm Nāea Chun; University of Hawaii at Manoa. College of Education. Curriculum Research & Development Group; Pihana nā Mamo (Project) (2006). Kapu: gender roles in traditional society. CRDG. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-1-58351-044-5. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

^ Malo, David, Hawaiian Antiquities. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Special Publication 2,

Second Edition. (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1951)

^ Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa, Native Land and Foreign Desires: Pehea Lā E Pono Ai? (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1992.),24

^ Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa, Native Land and Foreign Desires: Pehea Lā E Pono Ai? (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1992.),25

^ "Got Religion?". Hawaii-guide.info. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

^ Valeri, Valerio (1985). Kingship and Sacrifice: Ritual and Society in Ancient Hawaii. University of Chicago Press. p. 231.

Akana, Alan Robert (2014). The Volcano Is Our Home: Nine Generations of a Hawaiian Family on Kilauea Volcano. Balboa Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-4525-8753-0.

^ Kamakau, Samuel Manaiakalani; Mary Kawena Pukui; Dorothy B. Barrère (1993). Tales and Traditions of the People of Old: Na MoʻOlelo a Ka PoʻE Kahiko. Booklines Hawaii Ltd. p. 64. ISBN 0-930897-71-4.

^ Kepelino (2007) [1932]. Martha Warren Beckwith, ed. Kepelino's Traditions of Hawaii. Bishop Museum Press. p. 56. ISBN 1-58178-060-5.

^ Pukui, Mary Kawena; E. W. Haertig; Catherine A. Lee (1972). Nana i ke Kumu: Look to the Source. 2. Honolulu: Hui Hanai. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-9616738-2-6.

^ Kirch, Patrick; Roger Curtis Green (2001). Hawaiki, Ancestral Polynesia: An Essay in Historical Anthropology. p. 80. ISBN 0-521-78879-X.

^ Pukui, Mary Kawena; E. W. Haertig; Catherine A. Lee (1972). Nana i ke Kumu: Look to the Source. 2. Honolulu: Hui Hanai. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-9616738-2-6.

^ Lee, Pali Jae (2007). Hoʻopono. Lightning Source Inc. p. 28. ISBN 0-9677253-7-2.

^ Dudley, Michael Kioni; Keoni Kealoha Agard (1990). A Hawaiian Nation: Man, Gods and Nature. Illustrated by Daniel K San Miguel. Nā Kāne O Ka Malo Press. p. 32. ISBN 1-878751-01-8.

^ Kamakau, Samuel Manaiakalani; Mary Kawena Pukui; Dorothy B. Barrère (1964). Ka Poʻe Kahiko: The People of Old. Translated by Mary Kawena Pukui. Bishop Museum Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-910240-32-9.

^ "Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana >> History". Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

^ Song, Jaymes (2007-05-27). "Booming development in Hawaii disturbs the dead". Oakland, CA, USA: Oakland Tribune. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

Song, Jaymes (2007-05-27). "Booming development in Hawaii disturbs the dead". Oakland, CA, USA: Oakland Tribune. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

(subscription required)

^ ab Long, Max Freedom (2009) [1954]. The Secret Science Behind Miracles. Wildside Press.

ISBN 1-4344-0499-4.

Further reading and resources

Beckwith, Martha Warren (1981) [1951]. The Kumulipo: A Hawaiian Creation Chant. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-0771-5.

Malo, David (2005) [1951]. Hawaiian Antiquities. Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 0-910240-15-9.

"Figure Marae 12, Mokumanamana (Necker Island), Hawai'i (1976.194)". In Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. April 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

"Stick God (Akua Ka'ai) Hawai'i (1979.206.1625)". In Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. April 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-29.