Ohio River

| Ohio River | |

The widest point on the Ohio River is just north of downtown Louisville, where it is one mile (1.6 km) wide | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| States | Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois |

Tributaries | |

| - left | Little Kanawha River, Kanawha River, Guyandotte River, Big Sandy River, Little Sandy River, Licking River, Kentucky River, Salt River, Green River, Cumberland River, Tennessee River |

| - right | Beaver River, Little Muskingum River, Muskingum River, Little Hocking River, Hocking River, Shade River, Scioto River, Little Miami River, Great Miami River, Wabash River |

| Cities | Pittsburgh, PA, East Liverpool, OH, Wheeling, WV, Parkersburg, WV, Huntington, WV, Ashland, KY, Cincinnati, OH, Louisville, KY, Owensboro, KY, Evansville, IN, Henderson, KY, Paducah, KY, Cairo, IL |

| Source | Allegheny River |

| - location | Allegany Township, Potter County, Pennsylvania |

| - elevation | 2,240 ft (683 m) |

| - coordinates | 41°52′22″N 77°52′30″W / 41.87278°N 77.87500°W / 41.87278; -77.87500 |

| Secondary source | Monongahela River |

| - location | Fairmont, West Virginia |

| - elevation | 880 ft (268 m) |

| - coordinates | 39°27′53″N 80°09′13″W / 39.46472°N 80.15361°W / 39.46472; -80.15361 |

| Source confluence | |

| - location | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania |

| - elevation | 730 ft (223 m) |

| - coordinates | 40°26′32″N 80°00′52″W / 40.44222°N 80.01444°W / 40.44222; -80.01444 |

| Mouth | Mississippi River |

| - location | at Cairo, Illinois / Ballard County, Kentucky |

| - elevation | 290 ft (88 m) |

| - coordinates | 36°59′12″N 89°07′50″W / 36.98667°N 89.13056°W / 36.98667; -89.13056Coordinates: 36°59′12″N 89°07′50″W / 36.98667°N 89.13056°W / 36.98667; -89.13056 |

| Length | 981 mi (1,579 km) |

| Basin | 189,422 sq mi (490,601 km2) |

| Discharge | for Cairo, Illinois |

| - average | 281,000 cu ft/s (7,957 m3/s) (1951–80)[1] |

| - max | 1,850,000 cu ft/s (52,386 m3/s) |

Ohio River basin | |

The Ohio River, which streams westward from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Cairo, Illinois, is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River in the United States. At the confluence, the Ohio is considerably bigger than the Mississippi (Ohio at Cairo: 281,500 cu ft/s (7,960 m3/s);[2] Mississippi at Thebes: 208,200 cu ft/s (5,897 m3/s)[3]) and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system.

The 981-mile (1,579 km) river flows through or along the border of six states, and its drainage basin includes parts of 15 states. Through its largest tributary, the Tennessee River, the basin includes many of the states of the southeastern U.S. It is the source of drinking water for three million people.[4]

The name "Ohio" comes from the Seneca, Ohi:yo', lit. "Good River".[5] The river had great significance in the history of the Native Americans, as numerous civilizations formed along its valley. For thousands of years, Native Americans used the river as a major transportation and trading route. Its waters connected communities. In the five centuries before European conquest, the Mississippian culture built numerous regional chiefdoms and major earthwork mounds in the Ohio Valley, such as Angel Mounds near Evansville, Indiana, as well as in the Mississippi Valley and the Southeast. The Osage, Omaha, Ponca and Kaw lived in the Ohio Valley, but under pressure from the Iroquois to the northeast, migrated west of the Mississippi River to Missouri, Arkansas and Oklahoma in the 17th century.

In 1669, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle led a French expedition to the Ohio River, becoming the first Europeans to see it. After European-American settlement, the river served as a border between present-day Kentucky and Indian Territories. It was a primary transportation route for pioneers during the westward expansion of the early U.S. In his Notes on the State of Virginia published in 1781–82, Thomas Jefferson stated: "The Ohio is the most beautiful river on earth. Its current gentle, waters clear, and bosom smooth and unbroken by rocks and rapids, a single instance only excepted."[6]

During the 19th century, the river was the southern boundary of the Northwest Territory. It is sometimes considered as the western extension of the Mason–Dixon Line that divided Pennsylvania from Maryland, and thus part of the border between free and slave territory, and between the Northern and Southern United States or Upper South. Where the river was narrow, it was the way to freedom for thousands of slaves escaping to the North, many helped by free blacks and whites of the Underground Railroad resistance movement.

The Ohio River is a climatic transition area, as its water runs along the periphery of the humid subtropical and humid continental climate areas. It is inhabited by fauna and flora of both climates. In winter, it regularly freezes over at Pittsburgh but rarely farther south toward Cincinnati and Louisville. At Paducah, Kentucky, in the south, near the Ohio's confluence with the Mississippi, it is ice-free year-round.

Contents

1 Gallery

2 Etymology

3 Geography and hydrography

3.1 Drainage basin

4 Geology

4.1 Upper Ohio River

4.2 Middle Ohio River

5 History

6 Pollution

7 River depth

8 Metropolitan areas

9 See also

10 Notes

11 References

12 Further reading

13 External links

Gallery

The Allegheny River, left, and Monongahela River join to form the Ohio River at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the largest metropolitan area on the river.

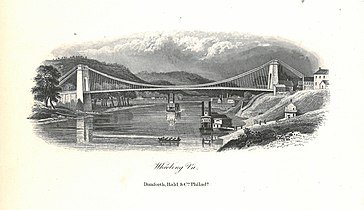

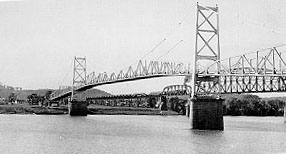

Built between 1849 and 1851, the Wheeling Suspension Bridge was the first bridge across the river.

Louisville, Kentucky, The deepest point of the Ohio River is a scour hole just below Cannelton locks and dam (river mile 720.7). The widest point of the river is at the confluence of the Ohio and the Mississippi rivers.

A barge hauls coal in the Louisville and Portland Canal, the only artificial portion of the Ohio River.

The Tall Stacks festival celebrates the riverboats of Cincinnati, Ohio, every three or four years.

Etymology

The name "Ohio" comes from the Seneca language (an Iroquoian language), Ohi:yo' (roughly pronounced oh-hee-yoh, with the vowel in "hee" held longer), a proper name derived from ohiːyoːh ("good river"), therefore literally translating to "Good River".[5][7] "Great river" and "large creek" have also been given as translations.[8][9]

Native Americans, including the Lenni Lenape and Iroquois, considered the Ohio and Allegheny rivers as the same, as is suggested by a New York State road sign on Interstate 86 that refers to the Allegheny River also as Ohi:yo';[10] the Geographic Names Information System lists O-hee-yo and O-hi-o as variant names for the Allegheny.[11]

An earlier Miami-Illinois language name was also applied to the Ohio River, Mosopeleacipi ("river of the Mosopelea" tribe). Shortened in the Shawnee language to pelewa thiipi, spelewathiipi or peleewa thiipiiki, the name evolved through variant forms such as "Polesipi", "Peleson", "Pele Sipi" and "Pere Sipi", and eventually stabilized to the variant spellings "Pelisipi", "Pelisippi" and "Pellissippi". Originally applied just to the Ohio River, the "Pelisipi" name later was variously applied back and forth between the Ohio River and the Clinch River in Virginia and Tennessee.[12][13] In his original draft of the Land Ordinance of 1784, Thomas Jefferson proposed a new state called "Pelisipia", to the south of the Ohio River, which would have included parts of present-day Eastern Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia.[12]

Geography and hydrography

Natural-color satellite image of the Wabash-Ohio confluence.

The Ohio River is formed by the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers at Point State Park in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. From there, it flows northwest through Allegheny and Beaver counties, before making an abrupt turn to the south-southwest at the West Virginia–Ohio–Pennsylvania triple-state line (near East Liverpool, Ohio; Chester, West Virginia; and Ohioville, Pennsylvania). From there, it forms the border between West Virginia and Ohio, upstream of Wheeling, West Virginia.

The river then follows a roughly southwest and then west-northwest course until Cincinnati, before bending to a west-southwest course for most of its length. The course forms the northern borders of West Virginia and Kentucky; and the southern borders of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, until it joins the Mississippi River at the city of Cairo, Illinois.

Major tributaries of the river, indicated by the location of the mouths, include:

Allegheny River – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Monongahela River – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Saw Mill Run – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Chartiers Creek – Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- Montour Run – Coraopolis, Pennsylvania

Beaver River – Rochester, Pennsylvania

- Breezewood Creek – Beaver, Pennsylvania

Raccoon Creek – Center Township

Little Beaver Creek – East Liverpool, Ohio

Wheeling Creek – Wheeling, West Virginia

Middle Island Creek – St. Marys, West Virginia

Little Muskingum River – Ohio

Duck Creek – Marietta, Ohio

Muskingum River – Marietta, Ohio

Little Kanawha River – Parkersburg, West Virginia

Hocking River – Hockingport, Ohio

Kanawha River – Point Pleasant, West Virginia

Guyandotte River – Huntington, West Virginia

Big Sandy River – Kentucky-West Virginia border

Little Sandy River – Greenup, Kentucky

Little Scioto River – Sciotoville, Ohio

Scioto River – Portsmouth, Ohio

- Kinniconick Creek – Vanceburg, Kentucky

Little Miami River – Cincinnati, Ohio

Licking River – Newport-Covington, Kentucky

Mill Creek – Cincinnati, Ohio

Great Miami River – Ohio-Indiana border

Kentucky River – Carrollton, Kentucky

Salt River – West Point, Kentucky

Green River – near Henderson, Kentucky

Wabash River – Indiana-Illinois-Kentucky border

Saline River – Illinois

Cumberland River – Smithland, Kentucky

Tennessee River – Paducah, Kentucky

Cache River – Illinois

Drainage basin

The Ohio's drainage basin covers 189,422 square miles (490,600 km2), encompassing the easternmost regions of the Mississippi Basin. The Ohio drains parts of 15 states in four regions.

- Northeast

New York: a small area of the southern border along the headwaters of the Allegheny.- Pennsylvania: a corridor from the southwestern corner to north central border.

- Mid-Atlantic/Upper South

- Maryland: a small corridor along the Youghiogheny River on the western border.

- West Virginia: all but the Eastern Panhandle.

- Kentucky: all but a small part in the extreme west drained directly by the Mississippi.

- Tennessee: all but a small part in the extreme west drained directly by the Mississippi, and a very small area in the southeastern corner which is drained by the Conasauga River.

Virginia: most of southwest Virginia.

North Carolina: the western quarter.

- Midwest

- Ohio: the southern two-thirds

- Indiana: all but the northern area.

- Illinois: the southeast quarter.

- Deep South

Georgia: the far northwest corner.

Alabama: the northern portion.

Mississippi: the northeast corner.

South Carolina: less than 1 square mile in the northwest.

Geology

Glacial Lake Ohio

From a geological standpoint, the Ohio River is young. The river formed on a piecemeal basis beginning between 2.5 and 3 million years ago. The earliest ice ages occurred at this time and dammed portions of north-flowing rivers. The Teays River was the largest of these rivers. The modern Ohio River flows within segments of the ancient Teays. The ancient rivers were rearranged or consumed by glaciers and lakes.

Upper Ohio River

The upper Ohio River formed when one of the glacial lakes overflowed into a south-flowing tributary of the Teays River. Prior to that event, the north-flowing Steubenville River (no longer in existence) ended between New Martinsville and Paden City, West Virginia. The south-flowing Marietta River (no longer in existence) ended between the present-day cities. The overflowing lake carved through the separating hill and connected the rivers. The floodwaters enlarged the small Marietta valley to a size more typical of a large river. The new large river subsequently drained glacial lakes and melting glaciers at the end of the Ice Age. The valley grew during and following the ice age. Many small rivers were altered or abandoned after the upper Ohio River formed. Valleys of some abandoned rivers can still be seen on satellite and aerial images of the hills of Ohio and West Virginia between Marietta, Ohio, and Huntington, West Virginia. As testimony to the major changes that occurred, such valleys are found on hilltops.[clarification needed]

Middle Ohio River

The middle Ohio River formed in a manner similar to formation of the upper Ohio River. A north-flowing river was temporarily dammed southwest of present-day Louisville, creating a large lake until the dam burst. A new route was carved to the Mississippi. Eventually the upper and middle sections combined to form what is essentially the modern Ohio River.

History

Steamboat "Morning Star", a Louisville and Evansville mail packet, in 1858.

Pre-Columbian inhabitants of eastern North America considered the Ohio part of a single river continuing on through the lower Mississippi. The combined Allegheny-Ohio river is 1,310 miles (2,110 km) long and carries the largest volume of water of any tributary of the Mississippi. The Indians and early explorers and settlers of the region also often considered the Allegheny to be part of the Ohio. The forks (the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers at what is now Pittsburgh) was considered a strategic military location.

French fur traders operated in the area, and France built forts along the Allegheny River. In 1669, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, led an expedition of French traders who became the first Europeans to see the river. He traveled from Canada and entered the headwaters of the Ohio, traveling as far as the Falls of Ohio at present-day Louisville before turning back. He returned to explore the river again in other expeditions. An Italian cartographer traveling with him created the first map of the Ohio River. La Salle claimed the Ohio Valley for France.

In 1749, Great Britain established the Ohio Company to settle and trade in the area. Exploration of the territory and trade with the Indians in the region near the Forks by British colonials from Pennsylvania and Virginia – both of which claimed the territory – led to conflict with the French. In 1763, following the Seven Years' War, France ceded the area to Britain.[14]

The 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix opened Kentucky to colonial settlement and established the Ohio River as a southern boundary for American Indian territory.[15] In 1774, the Quebec Act restored the land east of the Mississippi River and north of the Ohio River to Quebec, in effect making the Ohio the southern boundary of Canada. This appeased the Canadien British subjects but angered the Thirteen Colonies. Lord Dunmore's War south of the Ohio river also contributed to giving the land north to Quebec to stop further encroachment of the British colonials on native land. During the American Revolution, in 1776 the British military engineer John Montrésor created a map of the river showing the strategic location of Fort Pitt, including specific navigational information about the Ohio River's rapids and tributaries in that area.[16] However, the Treaty of Paris (1783) gave the entire Ohio Valley to the United States.

The economic connection of the Ohio Country to the East was significantly increased in 1818 when the National Road being built westward from Cumberland, Maryland reached Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia), providing an easier overland connection from the Potomac River to the Ohio River.[17]

Louisville was founded at the only major natural navigational barrier on the river, the Falls of the Ohio. The Falls were a series of rapids where the river dropped 26 feet (7.9 m) in a stretch of about 2 miles (3.2 km). In this area, the river flowed over hard, fossil-rich beds of limestone. The first locks on the river – the Louisville and Portland Canal – were built to circumnavigate the falls between 1825 and 1830. Fears that Louisville's transshipment industry would collapse proved ill-founded: the increasing size of steamships and barges on the river meant that the outdated locks could only service the smallest vessels until well after the Civil War. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers improvements were expanded again in the 1960s, forming the present-day McAlpine Locks and Dam.

Because the Ohio River flowed westward, it became a convenient means of westward movement by pioneers traveling from western Pennsylvania. After reaching the mouth of the Ohio, settlers would travel north on the Mississippi River to St. Louis, Missouri. There, some continued on up the Missouri River, some up the Mississippi, and some further west over land routes. In the early 19th century, river pirates such as Samuel Mason, operating out of Cave-In-Rock, Illinois, waylaid travelers on their way down the river. They killed travelers, stealing their goods and scuttling their boats. The folktales about Mike Fink recall the keelboats used for commerce in the early days of European settlement. The Ohio River boatmen were the inspiration for performer Dan Emmett, who in 1843 wrote the song "The Boatman's Dance".

Trading boats and ships traveled south on the Mississippi to New Orleans, and sometimes beyond to the Gulf of Mexico and other ports in the Americas and Europe. This provided a much-needed export route for goods from the west, since the trek east over the Appalachian Mountains was long and arduous. The need for access to the port of New Orleans by settlers in the Ohio Valley led to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Because the river is the southern border of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, it was part of the border between free states and slave states in the years before the American Civil War. The expression "sold down the river" originated as a lament of Upper South slaves, especially from Kentucky, who were shipped via the Ohio and Mississippi to cotton and sugar plantations in the Deep South.[18][19] Before and during the Civil War, the Ohio River was called the "River Jordan" by slaves crossing it to escape to freedom in the North via the Underground Railroad.[20] More escaping slaves, estimated in the thousands, made their perilous journey north to freedom across the Ohio River than anywhere else across the north-south frontier. Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, the bestselling novel that fueled abolitionist work, was the best known of the anti-slavery novels that portrayed such escapes across the Ohio. The times have been expressed by 20th-century novelists as well, such as the Nobel Prize-winning Toni Morrison, whose novel Beloved was adapted as a film of the same name. She also composed the libretto for the opera Margaret Garner (2005), based on the life and trial of an enslaved woman who escaped with her family across the river.

The Ohio River is considered to separate Midwestern Great Lakes states from the Upper South states, which were historically border states in the Civil War.

The colonial charter for Virginia defined its territory as extending to the north shore of the Ohio, so that the riverbed was "owned" by Virginia. Where the river serves as a boundary between states today, Congress designated the entire river to belong to the states on the east and south, i.e., West Virginia and Kentucky at the time of admission to the Union, that were divided from Virginia. Thus Wheeling Island, the largest inhabited island in the Ohio River, belongs to West Virginia, although it is closer to the Ohio shore than to the West Virginia shore. Kentucky brought suit against Indiana in the early 1980s because of the building of the Marble Hill nuclear power plant in Indiana, which would have discharged its waste water into the river.

The U.S. Supreme Court held that Kentucky's jurisdiction (and, implicitly, that of West Virginia) extended only to the low-water mark of 1793 (important because the river has been extensively dammed for navigation, so that the present river bank is north of the old low-water mark.) Similarly, in the 1990s, Kentucky challenged Illinois' right to collect taxes on a riverboat casino docked in Metropolis, citing its own control of the entire river. A private casino riverboat that docked in Evansville, Indiana, on the Ohio River opened about the same time. Although such boats cruised on the Ohio River in an oval pattern up and down, the state of Kentucky soon protested. Other states had to limit their cruises to going forwards, then reversing and going backwards on the Indiana shore only. Both Illinois and Indiana have long since changed their laws to allow riverboat casinos to be permanently docked, with Illinois changing in 1999 and Indiana in 2002.

In the early 1980s, the Falls of the Ohio National Wildlife Conservation Area was established at Clarksville, Indiana.

The confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers is at Cairo, Illinois.

Carl D. Perkins Bridge in Portsmouth, Ohio with Ohio River and Scioto River tributary on right.

Silver Bridge in Point Pleasant, West Virginia which collapsed into the Ohio River on December 15, 1967, killing 46 persons.

Mouth of the Ohio, as it feeds into the Mississippi.

Cave-in-rock, view on the Ohio (circa 1832, Cave-In-Rock, Illinois): aquatint by Karl Bodmer from the book Maximilian, Prince of Wied's Travels in the Interior of North America, during the years 1832–1834

Pollution

The Ohio River as a whole is ranked as the most polluted river in the US based on 2009 and 2010 data although the more industrial and regional Ohio tributary, Monongahela River, ranked behind 16 other American rivers for pollution at number 17.[21]

The Ohio River was polluted with hundreds of thousands of pounds of PFOA by DuPont chemical company, from an outflow pipe, for several decades beginning in the 1950s.[22]

River depth

Lawrenceburg, Indiana, is one of many towns that use the Ohio as a shipping avenue.

The Ohio River is a naturally shallow river that was artificially deepened by a series of dams. The natural depth of the river varied from about 3 to 20 feet (0.91 to 6.10 m). The dams raise the water level and have turned the river largely into a series of reservoirs, eliminating shallow stretches and allowing for commercial navigation. From its origin to Cincinnati, the average depth is approximately 15 feet (5 m). The largest immediate drop in water level is below the McAlpine Locks and Dam at the Falls of the Ohio at Louisville, Kentucky, where flood stage is reached when the water reaches 23 feet (7 m) on the lower gauge. However, the river's deepest point is 168 feet (51 m) on the western side of Louisville, Kentucky. From Louisville, the river loses depth very gradually until its confluence with the Mississippi at Cairo, Illinois, where it has an approximate depth of 19 feet (6 m).

Water levels for the Ohio River from Smithland Lock and Dam upstream to Pittsburgh are predicted daily by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Ohio River Forecast Center.[23] The water depth predictions are relative to each local flood plain based upon predicted rainfall in the Ohio River basin in five reports as follows:

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to Hannibal Locks and Dam, Ohio (including the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers)

Willow Island Locks and Dam, Ohio, to Greenup Lock and Dam, Kentucky (including the Kanawha River)

Portsmouth, Ohio, to Markland Locks and Dam, Kentucky

McAlpine Locks and Dam, Kentucky, to Cannelton Locks and Dam, Indiana

Newburgh Lock and Dam, Indiana, to Golconda, Illinois

The water levels for the Ohio River from Smithland Lock and Dam to Cairo, Illinois, are predicted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Lower Mississippi River Forecast Center.[24]

Smithland Lock and Dam, Illinois, to Cairo, Illinois

Metropolitan areas

| Metro Area | Population |

|---|---|

Pittsburgh | 2.4 million |

Cincinnati | 2.2 million |

Louisville | 1.5 million |

Huntington-Ashland | 365,419 |

Evansville | 358,000 |

Parkersburg | 160,000 |

Wheeling | 145,000 |

Weirton-Steubenville | 132,000 |

Owensboro | 112,000 |

See also

- Geography of the United States

- Islands of the Midwest

- List of crossings of the Ohio River

List of islands of West Virginia (including islands on Ohio River)- List of locks and dams of the Ohio River

- List of rivers of Indiana

- List of rivers of Kentucky

- List of rivers of Ohio

- List of rivers of Pennsylvania

- List of variant names of the Ohio River

- Ohio and Erie Canal

- Ohio River Bridges Project

- Ohio River flood of 1937

- Watersheds of Illinois

- List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem)

- Ohio River Valley AVA

- Ohio Valley in Kentucky

- Ohio River Trail

- Ohio River Water Trail

Notes

^ Leeden, Frits van der; Troise, Fred L.; Todd, David Keith (1990). The Water Encyclopedia (2nd ed.). Chelsea, Mich.: Lewis Publishers. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-87371-120-3..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Frits van der Leeden, Fred L. Troise, David Keith Todd: The Water Encyclopedia, 2nd edition, p. 126, Chelsea, Mich. (Lewis Publishers), 1990,

ISBN 0-87371-120-3 (long term mean discharge)

^ USGS stream gage 07022000 Mississippi River at Thebes, IL (long term mean discharge)

^ "Ohio River Facts".

^ ab Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

^ Jefferson, Thomas, 1743–1826. Notes on the State of Virginia Archived August 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.; the single instance refers to the former rapids near Louisville.

^ "Native Ohio". American Indian Studies. Ohio State University. Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2007.Ohio comes from the Seneca (Iroquoian) ohiiyo' 'good river'

^ "Quick Facts About the State of Ohio". Ohio History Central. Retrieved July 2, 2010.From Iroquois word meaning 'great river'

^ Mithun, Marianne (1999). "Borrowing". The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 311–3. ISBN 978-0-521-29875-9.Ohio ('large creek')

^ Stewart, George R. (1967). Names on the Land. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-938530-02-2.

^ "Allegheny River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

^ ab "The Winding River Home: Pellissippi State researches the meaning of 'Pellissippi'". Pellissippi State News. Pellissippi State Community College. June 7, 2017. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

^ "Shawnees Webpage". Shawnee's Reservation. 1997. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

^ "History of Seneca County: Containing a Detailed Narrative of the Principal Events That Have Occurred Since Its First Settlement Down to the Present Time; a History of the Indians That Formerly Resided Within Its Limits; Geographical Descriptions, Early Customs, Biographical Sketches, &c., &c., With an Introd., Containing a Brief History of the State, From the Discovery of the Mississippi River Down to the Year 1817, to the Whole of Which Is Added an Appendix, Containing Tabular Views, &c". Mocavo.

^ *Taylor, Alan (2006). The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 44, see map on 39. ISBN 978-0-679-45471-7.

^ Montrésor, John (1776). "Map of the Ohio River from Fort Pitt". World Digital Library. Pennsylvania. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

^ Fowler, Thaddeus Mortimer (1906). "Bird's Eye View of Cumberland, Maryland 1906". World Digital Library. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

^ mginter. "KET's Underground Railroad – Behind the Scenes – Guy Mendes".

^ "Put in Master's Pocket: Interstate Slave Trading and the Black Appalachian Diaspora" Archived August 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

^ mginter. "KET's Underground Railroad – Community Research".

^ "Report: Ohio River most polluted in U.S." Pittsburgh Business Times. March 23, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

^ Rich, Nathaniel (January 6, 2016). "The Lawyer Who Became DuPont's Worst Nightmare". New York Times.

^ "Ohio RFC". US Department of Commerce, NOAA, National Weather Service. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

^ "Lower Mississippi RFC". US Department of Commerce, NOAA, National Weather Service. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

References

- Hay, Jerry (2010). Ohio River Guidebook, 1st Edition

Further reading

Dunn, J. P. (December 1912). "Names of the Ohio River". The Indiana Quarterly Magazine of History. 8 (4): 166–70. doi:10.2307/27785389 (inactive 2018-09-21). JSTOR 27785389.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ohio River. |

- Ohio River Flows and Forecasts

- U.S. Geological Survey: PA stream gauging stations

Ohio River Forecast Center, which issues official river forecasts for the Ohio River and its tributaries from Smithland Lock and Dam upstream

Lower Mississippi River Forecast Center, which issues official river forecasts for the Ohio River and its tributaries downstream of Smithland Lock and Dam

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

"Ohio River". Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 (11th ed.). 1911.

"Ohio River". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

"Ohio River". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Ohio, a river of the United States". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

"Ohio, a river of the United States". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.