Mutiny on the Bounty

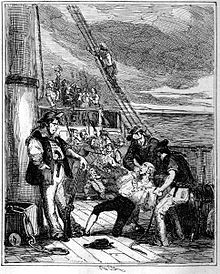

Fletcher Christian and the mutineers cast Lieutenant William Bligh and 18 others adrift; 1790 painting by Robert Dodd

The mutiny on the Royal Navy vessel HMS Bounty occurred in the south Pacific on 28 April 1789. Disaffected crewmen, led by Acting Lieutenant Fletcher Christian, seized control of the ship from their captain Lieutenant William Bligh and set him and 18 loyalists adrift in the ship's open launch. The mutineers variously settled on Tahiti or on Pitcairn Island. Bligh meanwhile completed a voyage of more than 3,500 nautical miles (6,500 km; 4,000 mi) in the launch to reach safety, and began the process of bringing the mutineers to justice.

Bounty had left England in 1787 on a mission to collect and transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the West Indies. A five-month layover in Tahiti, during which many of the men lived ashore and formed relationships with native Polynesians, proved harmful to discipline. Relations between Bligh and his crew deteriorated after he began handing out increasingly harsh punishments, criticism and abuse, Christian being a particular target. After three weeks back at sea, Christian and others forced Bligh from the ship. Twenty-five men remained on board afterwards, including loyalists held against their will and others for whom there was no room in the launch.

After Bligh reached England in April 1790, the Admiralty despatched HMS Pandora to apprehend the mutineers. Fourteen were captured in Tahiti and imprisoned on board Pandora, which then searched without success for Christian's party that had hidden on Pitcairn Island. After turning back towards England, Pandora ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef, with the loss of 31 crew and four prisoners from Bounty. The 10 surviving detainees reached England in June 1792 and were court martialled; four were acquitted, three were pardoned and three were hanged.

Christian's group remained undiscovered on Pitcairn until 1808, by which time only one mutineer, John Adams, remained alive. Almost all his fellow-mutineers, including Christian, had been killed, either by each other or by their Polynesian companions. No action was taken against Adams; descendants of the mutineers and their Tahitian captives live on Pitcairn into the 21st century. The generally accepted view of Bligh as an overbearing monster and Christian as a tragic victim of circumstances, as depicted in well-known film accounts, has been challenged by late 20th- and 21st-century historians from whom a more sympathetic picture of Bligh has emerged.

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Bounty and her mission

1.2 Bligh

1.3 Crew

2 Expedition

2.1 To Cape Horn

2.2 Cape to Pacific

2.3 Tahiti

2.4 Towards home

3 Mutiny

3.1 Seizure

3.2 Bligh's open-boat voyage

3.3 Bounty under Christian

3.4 Mutineers divided

4 Retribution

4.1 HMS Pandora mission

4.2 Court martial, verdict, and sentences

4.3 Aftermath

5 Pitcairn

5.1 Settlement

5.2 Discovery

6 Cultural impact

6.1 Biographies and history

6.2 Dramatic and documentary films

7 Notes and references

8 Further reading

9 External links

Background

Bounty and her mission

A 1960 reconstruction of HMS Bounty

His Majesty's Armed Vessel (HMAV) Bounty, or HMS Bounty, was built in 1784 at the Blaydes shipyard in Hull, Yorkshire as a collier named Bethia. She was renamed after being purchased by the Royal Navy for £1,950 in May 1787.[1] She was three-masted, 91 feet (28 m) long overall and 25 feet (7.6 m) across at her widest point, and registered at 230 tons burthen.[2] Her armament was four short four-pounder carriage guns and ten half-pounder swivel guns, supplemented by small arms such as muskets.[3] As she was rated by the Admiralty as a cutter, the smallest category of warship, her commander would be a lieutenant rather than a post-captain and would be the only commissioned officer on board. Nor did a cutter warrant the usual detachment of Marines that naval commanders could use to enforce their authority.[4][n 1]

Bounty had been acquired to transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti (then rendered "Otaheite"), a Polynesian island in the south Pacific, to the British colonies in the West Indies. The expedition was promoted by the Royal Society and organised by its president Sir Joseph Banks, who shared the view of Caribbean plantation owners that breadfruit might grow well there and provide cheap food for the slaves.[8]Bounty was refitted under Banks' supervision at Deptford Dockyard on the River Thames. The great cabin, normally the ship's captain's quarters, was converted into a greenhouse for over a thousand potted breadfruit plants, with glazed windows, skylights, and a lead-covered deck and drainage system to prevent the waste of fresh water.[9] The space required for these arrangements in the small ship meant that the crew and officers would endure severe overcrowding for the duration of the long voyage.[10]

Bligh

Lieutenant William Bligh, captain of HMS Bounty

With Banks' agreement, command of the expedition was given to Lieutenant William Bligh,[11] whose experiences included Captain James Cook's third and final voyage (1776–80) in which he had served as sailing master, or chief navigator, on HMS Resolution.[n 2] Bligh was born in Plymouth in 1754 into a family of naval and military tradition—Admiral Sir Richard Rodney Bligh was his third cousin.[11][12] Appointment to Cook's ship at the age of 21 had been a considerable honour, although Bligh believed that his contribution was not properly acknowledged in the expedition's official account.[14] With the 1783 ending of the eight-year American War of Independence and subsequent renewal of conflict with France—which had recognised and allied with the new United States in 1778—the vast Royal Navy was reduced in size, and Bligh found himself ashore on half-pay.[15]

After a period of idleness, Bligh took temporary employment in the mercantile service and in 1785 was captain of the Britannia, a vessel owned by his wife's uncle Duncan Campbell.[16] Bligh assumed the prestigious Bounty appointment on 16 August 1787, at a considerable financial cost; his lieutenant's pay of four shillings a day (£70 a year) contrasted with the £500 a year he had earned as captain of Britannia. Because of the limited number of warrant officers allowed on Bounty, Bligh was also required to act as the ship's purser.[17][18] His sailing orders stated that he was to enter the Pacific via Cape Horn around South America and then, after collecting the breadfruit plants, sail westward through the Endeavour Strait and across the Indian and South Atlantic Oceans to the West Indies islands in the Caribbean. Bounty would thus complete a circumnavigation of the Earth in the Southern Hemisphere.[19]

Crew

Bounty's complement was 46 men, comprising 44 Royal Navy seamen (including Bligh) and two civilian botanists. Directly beneath Bligh were his warrant officers, appointed by the Navy Board and headed by the sailing master John Fryer.[20] The other warrant officers were the boatswain, the surgeon, the carpenter, and the gunner.[21] To the two master's mates and two midshipmen were added several honorary midshipmen—so-called "young gentlemen" who were aspirant naval officers. These signed the ship's roster as able seamen, but were quartered with the midshipmen and treated on equal terms with them.[22]

Most of Bounty's crew were chosen by Bligh or were recommended to him by influential patrons. William Peckover the gunner and Joseph Coleman the armourer had been with Cook and Bligh on HMS Resolution;[23] several others had sailed under Bligh more recently on the Britannia. Among these was the 23-year-old Fletcher Christian, who came from a wealthy Cumberland family descended from Manx gentry. Christian had chosen a life at sea rather than the legal career envisaged by his family.[24] He had twice voyaged with Bligh to the West Indies, and the two had formed a master-pupil relationship through which Christian had become a skilled navigator.[25] Christian was willing to serve on Bounty without pay as one of the "young gentlemen";[26] Bligh gave him one of the salaried master's mate's berths.[25] Another of the young gentlemen recommended to Bligh was 15-year-old Peter Heywood, also from a Manx family and a distant relation of Christian's. Heywood had left school at 14 to spend a year on HMS Powerful, a harbour-bound training vessel at Plymouth.[27] His recommendation to Bligh came from Richard Betham, a Heywood family friend who was Bligh's father-in-law.[22]

The two botanists, or "gardeners", were chosen by Banks. The chief botanist, David Nelson, was a veteran of Cook's third expedition who had been to Tahiti and had learned some of the natives' language.[28] Nelson's assistant William Brown was a former midshipman who had seen naval action against the French.[23] Banks also helped to secure the official midshipmen's berths for two of his protégés, Thomas Hayward and John Hallett.[29] Overall, Bounty's crew was relatively youthful, the majority being under 30;[30] at the time of departure, Bligh was 33 years old. Among the older crew members were the 39-year-old Peckover, who had sailed on all three of Cook's voyages, and Lawrence Lebogue, a year older and formerly sailmaker on the Britannia.[31] The youngest aboard were Hallett and Heywood, both 15 when they left England.[32]

Living space on the ship was allocated on the basis of rank. Bligh, having yielded the great cabin,[32] occupied private sleeping quarters with an adjacent dining area or pantry on the starboard side of the ship, and Fryer a small cabin on the opposite side. The surgeon Thomas Huggan, the other warrant officers, and Nelson the botanist had tiny cabins on the lower deck,[33] while the master's mates and the midshipmen, together with the young gentlemen, berthed together in an area behind the captain's dining room known as the cockpit; as junior or prospective officers, they were allowed use of the quarterdeck.[20] The other ranks had their quarters in the forecastle, a windowless unventilated area measuring 36 by 22 feet (11.0 by 6.7 m) with headroom of 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m).[34]

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .multicol-float{width:auto!important}}.mw-parser-output .multicol-float{width:30em}

| Name | Rank or function |

|---|---|

William Bligh | Lieutenant, Royal Navy: Ship's captain |

John Fryer | Warrant officer: Sailing master |

William Cole | Warrant officer: Boatswain |

William Peckover | Warrant officer: Gunner |

William Purcell | Warrant officer: Carpenter |

Thomas Huggan | Ship's surgeon |

Fletcher Christian | Master's mate |

William Elphinstone | Master's mate |

Thomas Ledward | Surgeon's mate |

John Hallett | Midshipman |

Thomas Hayward | Midshipman |

Peter Heywood | Honorary midshipman |

George Stewart | Honorary midshipman |

Robert Tinkler | Honorary midshipman |

Edward "Ned" Young | Honorary midshipman |

David Nelson | Botanist (civilian) |

William Brown | Assistant gardener (civilian) |

| Name | Rank or function |

|---|---|

Peter Linkletter | Quartermaster |

John Norton | Quartermaster |

George Simpson | Quartermaster's mate |

James Morrison | Boatswain's mate |

John Mills | Gunner's mate |

Charles Norman | Carpenter's mate |

Thomas McIntosh | Carpenter's mate |

Lawrence Lebogue | Sailmaker |

Charles Churchill | Master-at-arms |

Joseph Coleman | Armourer |

John Samuel | Captain's clerk |

John Smith | Captain's servant |

Henry Hillbrant | Cooper |

Thomas Hall | Cook |

Robert Lamb | Butcher |

William Muspratt | Assistant cook |

Thomas Burkett | Able seaman |

Michael Byrne (or "Byrn") | Able seaman – musician |

Thomas Ellison | Able seaman |

William McCoy (or "McKoy") | Able seaman |

Isaac Martin | Able seaman |

John Millward | Able seaman |

Matthew Quintal | Able seaman |

Richard Skinner | Able seaman |

John Adams ("Alexander Smith") | Able seaman |

John Sumner | Able seaman |

Matthew Thompson | Able seaman |

James Valentine | Able seaman |

John Williams | Able seaman |

Expedition

To Cape Horn

On 15 October 1787, Bounty left Deptford for Spithead, in the English Channel, to await final sailing orders.[36][n 3] Adverse weather delayed arrival at Spithead until 4 November. Bligh was anxious to depart quickly, to reach Cape Horn before the end of the short southern summer,[38] but the Admiralty did not accord him high priority and delayed issuing the orders for a further three weeks. When Bounty finally sailed on 28 November, the ship was trapped by contrary winds and unable to clear Spithead until 23 December.[39][40] With the prospect of a passage around Cape Horn now in serious doubt, Bligh received permission from the Admiralty to take, if necessary, an alternative route to Tahiti via the Cape of Good Hope.[41]

As the ship settled into her sea-going routine, Bligh introduced Cook's strict discipline regarding sanitation and diet. According to the expedition's historian Sam McKinney, Bligh enforced these rules "with a fanatical zeal, continually fuss[ing] and fum[ing] over the cleanliness of his ship and the food served to the crew."[42] He replaced the navy's traditional watch system of alternating four-hour spells on and off duty with a three-watch system, whereby each four-hour duty was followed by eight hours' rest.[43] For the crew's exercise and entertainment, he introduced regular music and dancing sessions.[44] Bligh's despatches to Campbell and Banks indicated his satisfaction; he had no occasion to administer punishment because, he wrote: "Both men and officers tractable and well disposed, & cheerfulness & content in the countenance of every one".[45] The only adverse feature of the voyage to date, according to Bligh, was the conduct of the surgeon Huggan, who was revealed as an indolent, unhygienic drunkard.[44]

From the start of the voyage, Bligh had established warm relations with Christian, according him a status which implied that he was Bligh's second-in-command rather than Fryer.[46][n 4] On 2 March, Bligh formalised the position by assigning Christian to the rank of Acting Lieutenant.[48][n 5] Fryer showed little outward sign of resentment at his junior's advancement, but his relations with Bligh significantly worsened from this point.[51] A week after the promotion, and on Fryer's insistence, Bligh ordered the flogging of Matthew Quintal, who received 12 lashes for "insolence and mutinous behaviour",[47] thereby destroying Bligh's expressed hope of a voyage free from such punishment.[52]

On 2 April, as Bounty approached Cape Horn, a strong gale and high seas began an unbroken period of stormy weather which, Bligh wrote, "exceeded what I had ever met with before ... with severe squalls of hail and sleet".[53] The winds drove the ship back; on 3 April, she was further north than she had been a week earlier.[54] Again and again, Bligh forced the ship forward, to be repeatedly repelled. On 17 April, he informed his exhausted crew that the sea had beaten them, and that they would turn and head for the Cape of Good Hope—"to the great joy of every person on Board", Bligh recorded.[55]

Cape to Pacific

On 24 May 1788, Bounty anchored in False Bay, east of the Cape of Good Hope, where five weeks were spent in repairs and reprovisioning.[56] Bligh's letters home emphasised how fit and well he and his crew were, by comparison with other vessels, and expressed hope that he would receive credit for this.[57] At one stage during the sojourn, Bligh lent Christian money, a gesture that the historian Greg Dening suggests might have sullied their relationship by becoming a source of anxiety and even resentment to the younger man.[58] In her account of the voyage, Caroline Alexander describes the loan as "a significant act of friendship", but one which Bligh ensured Christian did not forget.[57]

After leaving False Bay on 1 July, Bounty set out across the southern Indian Ocean on the long voyage to their next port of call, Adventure Bay in Tasmania. They passed the remote Île Saint-Paul, a small uninhabited island which Bligh knew from earlier navigators contained fresh water and a hot spring, but he did not attempt a landing. The weather was cold and wintry, conditions akin to the vicinity of Cape Horn, and it was difficult to take navigational observations, but Bligh's skill was such that on 19 August he sighted Mewstone Rock, on the south-west corner of Tasmania and, two days later, made anchorage in Adventure Bay.[59]

Matavai Bay, Tahiti, as painted by William Hodges in 1776

The Bounty party spent their time at Adventure Bay in recuperation, fishing, replenishment of water casks, and felling timber. There were peaceful encounters with the native population.[59] The first sign of overt discord between Bligh and his officers occurred when the captain exchanged angry words with William Purcell the carpenter over the latter's methods for cutting wood.[60][n 6] Bligh ordered Purcell back to the ship and, when the carpenter stood his ground, Bligh withheld his rations, which "immediately brought him to his senses", according to Bligh.[60]

Further clashes occurred on the final leg of the journey to Tahiti. On 9 October, Fryer refused to sign the ship's account books unless Bligh provided him with a certificate attesting to his complete competence throughout the voyage. Bligh would not be coerced. He summoned the crew and read the Articles of War, at which Fryer backed down.[62] There was also trouble with the surgeon Huggan, whose careless blood-letting of able seaman James Valentine while treating him for asthma led to the seaman's death from a blood infection.[63] To cover his error, the surgeon reported to Bligh that Valentine had died from scurvy,[64] which led Bligh to apply his own medicinal and dietary antiscorbutic remedies to the entire ship's company.[65] By now, Huggan was almost incapacitated with drink, until Bligh confiscated his supply. Huggan briefly returned to duty; before Bounty's arrival in Tahiti, he examined all on board for signs of venereal disease and found none.[66]Bounty came to anchor in Matavai Bay, Tahiti on 26 October 1788, concluding a journey of 27,086 nautical miles (50,163 km; 31,170 mi).[67]

Tahiti

Bligh's first action on arrival was to secure the co-operation of the local chieftains. The paramount chief Tynah remembered Bligh from Cook's voyage 15 years previously, and greeted him warmly. Bligh presented the chiefs with gifts and informed them that their own "King George" wished in return only breadfruit plants. They happily agreed with this simple request.[68] Bligh assigned Christian to lead a shore party charged with establishing a compound in which the plants would be nurtured.[69]

A Polynesian woman, painted in 1777 by John Webber

Whether based ashore or on board, the men's duties during Bounty's five-month stay in Tahiti were relatively light. Many led promiscuous lives among the native women—altogether, 18 officers and men, including Christian, received treatment for venereal infections[70]—while others took regular partners.[71] Christian formed a close relationship with a Polynesian woman named Mauatua, to whom he gave the name "Isabella" after a former sweetheart from Cumberland.[72] Bligh remained chaste himself,[73] but was tolerant of his men's activities, unsurprised that they should succumb to temptation when "the allurements of dissipation are beyond any thing that can be conceived".[74] Nevertheless, he expected them to do their duty efficiently, and was disappointed to find increasing instances of neglect and slackness on the part of his officers. Infuriated, he wrote: "Such neglectful and worthless petty officers I believe were never in a ship such as are in this".[70]

Huggan died on 10 December. Bligh attributed this to "the effects of intemperance and indolence ... he never would be prevailed on to take half a dozen turns upon deck at a time, through the whole course of the voyage".[75] For all his earlier favoured status, Christian did not escape Bligh's wrath. He was often humiliated by the captain—sometimes in front of the crew and the Tahitians—for real or imagined slackness,[70] while severe punishments were handed out to men whose carelessness had led to the loss or theft of equipment. Floggings, rarely administered during the outward voyage, now became increasingly common.[76] On 5 January 1789 three members of the crew—Charles Churchill, John Millward and William Muspratt—deserted, taking a small boat, arms and ammunition. Muspratt had recently been flogged for neglect. Among the belongings Churchill left on the ship was a list of names that Bligh interpreted as possible accomplices in a desertion plot—the captain later asserted that the names included those of Christian and Heywood. Bligh was persuaded that his protégé was not planning to desert, and the matter was dropped. Churchill, Millward and Muspratt were found after three weeks and, on their return to the ship, were flogged.[76]

From February onwards, the pace of work increased; more than 1,000 breadfruit plants were potted and carried into the ship, where they filled the great cabin.[77] The ship was overhauled for the long homeward voyage, in many cases by men who regretted the forthcoming departure and loss of their easy life with the Tahitians. Bligh was impatient to be away, but as Richard Hough observes in his account, he "failed to anticipate how his company would react to the severity and austerity of life at sea ... after five dissolute, hedonistic months at Tahiti".[78] The work was done by 1 April 1789, and four days later, after an affectionate farewell from Tynah and his queen, Bounty left the harbour.[77]

Towards home

In their Bounty histories, both Hough and Alexander maintain that the men were not at a stage close to mutiny, however sorry they were to leave Tahiti. The journal of James Morrison, the boatswain's mate, supports this.[79][80][n 7] The events that followed, Hough suggests, were determined in the three weeks following the departure, when Bligh's anger and intolerance reached paranoid proportions. Christian was a particular target, always seeming to bear the brunt of the captain's rages.[82] Unaware of the effects of his behaviour on his officers and crew,[14] Bligh would forget these displays instantly and attempt to resume normal conversation.[79]

On 22 April 1789, Bounty arrived at Nomuka, in the Friendly Islands (now called Tonga), intending to pick up wood, water, and further supplies on the final scheduled stop before the Endeavour Strait.[83] Bligh had visited the island with Cook, and knew that the inhabitants could behave unpredictably. He put Christian in charge of the watering party and equipped him with muskets, but at the same time ordered that the arms should be left in the boat, not carried ashore.[83] Christian's party was harassed and threatened continually but were unable to retaliate, having been denied the use of arms. He returned to the ship with his task incomplete, and was cursed by Bligh as "a damned cowardly rascal".[84] Further disorder ashore resulted in the thefts of a small anchor and an adze, for which Bligh further berated Fryer and Christian.[85] In an attempt to recover the missing property, Bligh briefly detained the island's chieftains on the ship, but to no avail. When he finally gave the order to sail, neither the anchor nor the adze had been restored.[86]

By 27 April, Christian was in a state of despair, depressed and brooding.[87][n 8] His mood was worsened when Bligh accused him of stealing coconuts from the captain's private supply. Bligh punished the whole crew for this theft, stopping their rum ration and reducing their food by half.[88][89] Feeling that his position was now intolerable, Christian considered constructing a raft with which he could escape to an island and take his chances with the natives. He may have acquired wood for this purpose from Purcell.[87][90] In any event, his discontent became common knowledge among his fellow officers. Two of the young gentlemen, George Stewart and Edward Young, urged him not to desert; Young assured him that he would have the support of almost all on board if he were to seize the ship and depose Bligh.[91] Stewart told him the crew were "ripe for anything".[87]

Mutiny

Seizure

Fletcher Christian and the mutineers seize HMS Bounty on 28 April 1789. Engraving by Hablot Knight Browne, 1841

In the early hours of 28 April 1789, Bounty lay about 30 nautical miles (56 km; 35 mi) south of the island of Tofua.[92] After a largely sleepless night, Christian had decided to act. He understood from his discussions with Young and Stewart which crewmen were his most likely supporters and, after approaching Quintal and Isaac Martin, he learned the names of several more. With the help of these men, Christian rapidly gained control of the upper deck; those who questioned his actions were ordered to keep quiet.[93] At about 05:15, Christian went below, dismissed Hallett (who was sleeping on the chest containing the ship's muskets), and distributed arms to his followers before making for Bligh's cabin.[94] Three men took hold of the captain and tied his hands, threatening to kill him if he raised the alarm;[95] Bligh "called as loudly as [he] could in hopes of assistance".[96] The commotion woke Fryer, who saw, from his cabin opposite, the mutineers frogmarching Bligh away. The mutineers ordered Fryer to "lay down again, and hold my tongue or I was a dead man".[94]

Bligh was brought to the quarterdeck, his hands bound by a cord held by Christian, who was brandishing a bayonet;[97] some reports maintained that Christian had a sounding plummet hanging from his neck so that he could jump overboard and drown himself if the mutiny failed.[94] Others who had been awakened by the noise left their berths and joined in the general pandemonium. It was unclear at this stage who were and who were not active mutineers. Hough describes the scene: "Everyone was, more or less, making a noise, either cursing, jeering or just shouting for the reassurance it gave them to do so".[97] Bligh shouted continually, demanding to be set free, sometimes addressing individuals by name, and otherwise exhorting the company generally to "knock Christian down!"[98] Fryer was briefly permitted on deck to speak to Christian, but was then forced below at bayonet-point; according to Fryer, Christian told him: "I have been in hell for weeks past. Captain Bligh has brought this on himself."[94]

Christian originally thought to cast Bligh adrift in Bounty's small jolly boat, together with his clerk John Samuel and the loyalist midshipmen Hayward and Hallett. This boat proved unseaworthy, so Christian ordered the launching of a larger ship's boat, with a capacity of around ten. However, Christian and his allies had overestimated the extent of the mutiny—at least half on board were determined to leave with Bligh. Thus the ship's largest boat, a 23-foot (7.0 m) launch, was put into the water.[99] During the following hours the loyalists collected their possessions and entered the boat. Among these was Fryer, who with Bligh's approval sought to stay on board—in the hope, he later claimed, that he would be able to retake the ship[94]—but Christian ordered him into the launch. Soon, the vessel was badly overloaded, with more than 20 persons and others still vying for places. Christian ordered the two carpenter's mates, Norman and McIntosh, and the armourer, Joseph Coleman, to return to the ship, considering their presence essential if he were to navigate Bounty with a reduced crew. Reluctantly they obeyed, beseeching Bligh to remember that they had remained with the ship against their will. Bligh assured them: "Never fear, lads, I'll do you justice if ever I reach England".[100]

Samuel saved the captain's journal, commission papers and purser's documents, but was forced to leave behind Bligh's maps and charts—15 years of navigational work.[94] The launch was supplied with about five days' food and water,[101] a sextant, compass and nautical tables, and Purcell's tool chest. At the last minute the mutineers threw four cutlasses down into the boat.[94] Of Bounty's complement—44 after the deaths of Huggan and Valentine—19 men were crowded into the launch, leaving it dangerously low in the water with only seven inches of freeboard.[101] The 25 men remaining on Bounty included the committed mutineers who had taken up arms, the loyalists detained against their will, and others for whom there was no room in the launch. At around 10:00 the line holding the launch to the ship was cut; a little later, Bligh ordered a sail to be raised. Their immediate destination was the nearby island of Tofua, clearly marked on the horizon by the plume of smoke rising from its volcano.[102]

Bligh's open-boat voyage

Map showing Bounty's movements in the Pacific Ocean, 1788–1790

Voyage of Bounty to Tahiti and to location of the mutiny, 28 April 1789

Course of Bligh's open-boat journey to Coupang, Timor, between 2 May and 14 June 1789

Movements of Bounty under Christian after the mutiny, from 28 April 1789 onwards

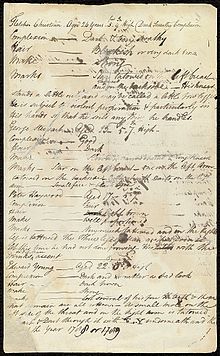

"Fletcher Christian. Aged 24 years – 5.9 High. Dark swarthy complexion..." The beginning of Bligh's list of mutineers, written during the open-boat voyage. Now in the collection of the National Library of Australia.

Bligh hoped to find water and food on Tofua, then proceed to the nearby island of Tongatapu to seek help from King Poulaho (whom he knew from his visit with Cook) in provisioning the boat for a voyage to the Dutch East Indies.[103] Ashore at Tofua, there were encounters with natives who were initially friendly but grew more menacing as time passed. On 2 May, four days after landing, Bligh realised that an attack was imminent. He directed his men back to the sea, shortly before the Tofuans seized the launch's stern rope and attempted to drag it ashore. Bligh coolly shepherded the last of his shore party and their supplies into the boat. In an attempt to free the rope from its captors, the quartermaster John Norton leapt into the water; he was immediately set upon and stoned to death.[104]

The launch escaped to the open sea, where the shaken crew reconsidered their options. A visit to Tongatapu, or any island landfall, might incur similarly violent consequences; their best chance of salvation, Bligh reckoned, lay in sailing directly to the Dutch settlement of Kupang in Timor, using the rations presently on board.[n 9] This was a journey of some 3,500 nautical miles (6,500 km; 4,000 mi) to the west, beyond the Endeavour Strait, and it would necessitate daily rations of an ounce of bread and a quarter-pint of water for each man. The plan was unanimously agreed.[106][107]

From the outset, the weather was wet and stormy, with mountainous seas that constantly threatened to overwhelm the boat.[108] When the sun appeared, Bligh noted in his daily journal that it "gave us as much pleasure as a winter's day in England".[109] Bligh endeavoured to continue his journal throughout the voyage, observing, sketching, and charting as they made their way west. To keep up morale, he told stories of his prior experiences at sea, got the men singing, and occasionally said prayers.[110] The launch made the first passage by Europeans through the Fiji Islands,[111] but they dared not stop because of the islanders' reputation for cannibalism.[112][n 10] On 17 May, Bligh recorded that "our situation was miserable; always wet, and suffering extreme cold ... without the least shelter from the weather".[114]

A week later with the skies clearing, birds began to appear, signalling a proximity to land.[115] On 28 May, the Great Barrier Reef was sighted; Bligh found a navigable gap and sailed the launch into a calm lagoon.[116] Late that afternoon, he ran the boat ashore on a small island which he named Restoration Island, where the men found oysters and berries in plentiful supply and were able to eat ravenously.[117][118] Over the next four days, the party island-hopped northward within the lagoon, aware that their movements were being closely monitored by natives on the mainland.[119] Strains were showing within the party; following a heated disagreement with Purcell, Bligh grabbed a cutlass and challenged the carpenter to fight. Fryer told Cole to arrest their captain, but backed down after Bligh threatened to kill him if he interfered.[120]

On 2 June, the launch cleared Cape York, the extreme northern point of the Australian continent. Bligh turned south-west, and steered through a maze of shoals, reefs, sandbanks, and small islands. The route taken was not the Endeavour Strait, but a narrower southerly passage later known as the Prince of Wales Channel. At 20:00 that evening, they reached the open Arafura Sea,[121] still 1,100 nautical miles (2,000 km; 1,300 mi) from Kupang.[122] The following eight days encompassed some of the toughest travel of the entire journey and, by 11 June, many were close to collapse. The next day, the coast of Timor was sighted: "It is not possible for me to describe the pleasure which the blessing of the sight of this land diffused among us", Bligh wrote.[123] On 14 June, with a makeshift Union Jack hoisted, they sailed into Kupang harbour.[114]

In Kupang, Bligh reported the mutiny to the authorities, and wrote to his wife: "Know then, my own Dear Betsey, I have lost the Bounty ..."[124] Nelson the botanist quickly succumbed to the harsh Kupang climate and died.[125] On 20 August, the party departed for Batavia (now Jakarta) to await a ship for Europe;[126] the cook Thomas Hall died there, having been ill for weeks.[127] Bligh obtained passages home for himself, his clerk Samuel, and his servant John Smith, and sailed on 16 October 1789.[128] Four of the remainder—the master's mate Elphinstone, the quartermaster Peter Linkletter, the butcher Robert Lamb and the assistant surgeon Thomas Ledward—all died either in Batavia or on their journeys home.[129][130]

Bounty under Christian

After the departure of Bligh's launch, Christian divided the personal effects of the departed loyalists among the remaining crew and threw the breadfruit plants into the sea.[131] He recognised that Bligh could conceivably survive to report the mutiny, and that anyway the non-return of Bounty would occasion a search mission, with Tahiti as its first port of call. Christian therefore headed Bounty towards the small island of Tubuai, some 450 nautical miles (830 km; 520 mi) south of Tahiti.[132] Tubuai had been discovered and roughly charted by Cook; except for a single small channel, it was entirely surrounded by a coral reef and could, Christian surmised, be easily defended against any attack from the sea.[133]

Tubuai, where Christian first attempted to settle; the island is almost totally surrounded by a coral reef

Bounty arrived at Tubuai on 28 May 1789. The reception from the native population was hostile; when a flotilla of war canoes headed for the ship, Christian used a four-pounder gun to repel the attackers. At least a dozen warriors were killed, and the rest scattered. Undeterred, Christian and an armed party surveyed the island, and decided it would be suitable for their purposes.[134] However, to create a permanent settlement, they needed compliant native labour and women. The most likely source for these was Tahiti, to which Bounty returned on 6 June. To ensure the co-operation of the Tahiti chiefs, Christian concocted a story that he, Bligh, and Captain Cook were founding a new settlement at Aitutaki. Cook's name ensured generous gifts of livestock and other goods and, on 16 June, the well-provisioned Bounty sailed back to Tubuai. On board were nearly 30 Tahitian men and women, some of whom were there by deception.[135][136]

For the next two months, Christian and his forces struggled to establish themselves on Tubuai. They began to construct a large moated enclosure—called "Fort George", after the British king—to provide a secure fortress against attack by land or sea.[135] Christian attempted to form friendly relations with the local chiefs, but his party was unwelcome.[137] There were persistent clashes with the native population, mainly over property and women, culminating in a pitched battle in which 66 islanders were killed and many wounded.[138] Discontent was rising among the Bounty party, and Christian sensed that his authority was slipping. He called a meeting to discuss future plans and offered a free vote. Eight remained loyal to Christian, the hard core of the active mutineers, but sixteen wished to return to Tahiti and take their chances there. Christian accepted this decision; after depositing the majority at Tahiti, he would "run before the wind, and ... land upon the first island the ship drives. After what I have done I cannot remain at Tahiti".[137]

Mutineers divided

When Bounty returned to Tahiti, on 22 September, the welcome was much less effusive than previously. The Tahitians had learned from the crew of a visiting British ship that the story of Cook and Bligh founding a settlement in Aitutaki was a fabrication, and that Cook had been long dead.[139] Christian worried that their reaction might turn violent, and did not stay long. Of the 16 men who had voted to settle in Tahiti, he allowed 15 ashore; Joseph Coleman was detained on the ship, as Christian required his skills as an armourer.[140]

That evening, Christian inveigled aboard Bounty a party of Tahitians, mainly women, for a social gathering. With the festivities under way, he cut the anchor rope and Bounty sailed away with her captive guests.[141] Coleman escaped by diving overboard and reached land.[140] Among the abducted group were six elderly women, for whom Christian had no use; he put them ashore on the nearby island of Mo'orea.[142]Bounty's complement now comprised nine mutineers—Christian, Young, Quintal, Brown, Martin, John Williams, William McCoy, John Mills, and John Adams (known by the crew as "Alexander Smith")[143]—and 20 Polynesians, of whom 14 were women.[144]

The 16 sailors on Tahiti began to organise their lives.[145] One group, led by Morrison and Tom McIntosh, began building a schooner, which they named Resolution after Cook's ship.[146] Morrison had not been an active mutineer; rather than waiting for recapture, he hoped to sail the vessel to the Dutch East Indies and surrender to the authorities there, hoping that such action would confirm his innocence. Morrison's group maintained ship's routine and discipline, even to the extent of holding divine service each Sunday.[147][n 11] Churchill and Matthew Thompson, on the other hand, chose to lead drunken and generally dissolute lives, which ended in the violent deaths of both. Churchill was murdered by Thompson, who was in turn killed by Churchill's native friends.[149] Others, such as Stewart and Heywood, settled into quiet domesticity; Heywood spent much of his time studying the Tahitian language.[145] He adopted native dress and, in accordance with the local custom, was heavily tattooed on his body.[150]

Retribution

HMS Pandora mission

When Bligh landed in England on 14 March 1790, news of the mutiny had preceded him and he was fêted as a hero. In October 1790 at a formal court-martial for the loss of Bounty, he was honourably acquitted of responsibility for the loss and was promoted to post-captain. As an adjunct to the court martial, Bligh brought charges against Purcell for misconduct and insubordination; the former carpenter received a reprimand.[151][152]

In November 1790, the Admiralty despatched the frigate HMS Pandora under Captain Edward Edwards to capture the mutineers and return them to England to stand trial.[153]Pandora arrived at Tahiti on 23 March 1791 and, within a few days, all 14 surviving Bounty men had either surrendered or been captured.[154] Edwards made no distinction between mutineers and those who claimed they had been detained on Bounty unwillingly;[155] all were incarcerated in a specially constructed prison erected on Pandora's quarterdeck, dubbed "Pandora's Box".[156]Pandora remained at Tahiti for five weeks while Captain Edwards unsuccessfully sought information on Bounty's whereabouts. The ship finally sailed on 8 May, to search for Christian and Bounty among the thousands of southern Pacific islands.[157] Apart from a few spars discovered at Palmerston Island, no traces of the fugitive vessel were found.[158] Edwards continued the search until August, when he turned west and headed for the Dutch East Indies.[159]

HMS Pandora foundering, 29 August 1791; 1831 etching by Robert Batty, from a sketch by Heywood

On 29 August 1791, Pandora ran aground on the outer Great Barrier Reef. The men in "Pandora's Box" were ignored as the regular crew attempted to prevent the ship from foundering. When Edwards gave the order to abandon ship, Pandora's armourer began to remove the prisoners' shackles, but the ship sank before he had finished. Heywood and nine other prisoners escaped; four Bounty men—George Stewart, Henry Hillbrant, Richard Skinner and John Sumner—drowned, along with 31 of Pandora's crew. The survivors, including the ten remaining prisoners, then embarked on an open-boat journey that largely followed Bligh's course of two years earlier. The prisoners were mostly kept bound hand and foot until they reached Kupang on 17 September.[160][161]

The prisoners were confined for seven weeks, at first in prison and later on a Dutch East India Company ship, before being transported to Cape Town.[162] On 5 April 1792, they embarked for England on a British warship, HMS Gorgon, and arrived at Portsmouth on 19 June. There they were transferred to the guardship HMS Hector to await trial. The prisoners included the three detained loyalists—Coleman, McIntosh and Norman—to whom Bligh had promised justice, the blind fiddler Michael Byrne (or "Byrn"), Heywood, Morrison, and four active mutineers: Thomas Burkett, John Millward, Thomas Ellison and William Muspratt.[163] Bligh, who had been given command of HMS Providence for a second breadfruit expedition, had left England in August 1791,[164] and thus would be absent from the pending court martial proceedings.[165]

Court martial, verdict, and sentences

Admiral Lord Hood, who presided over the Bounty court martial

The court martial opened on 12 September 1792 on HMS Duke in Portsmouth harbour, with Vice-Admiral Lord Hood, Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth, presiding.[166] Heywood's family secured him competent legal advisers;[167] of the other defendants, only Muspratt employed legal counsel.[168] The survivors of Bligh's open-boat journey gave evidence against their former comrades—the testimonies from Thomas Hayward and John Hallett were particularly damaging to Heywood and Morrison, who each maintained their innocence of any mutinous intention and had surrendered voluntarily to Pandora.[169] The court did not challenge the statements of Coleman, McIntosh, Norman and Byrne, all of whom were acquitted.[170] On 18 September the six remaining defendants were found guilty of mutiny and were sentenced to death by hanging, with recommendations of mercy for Heywood and Morrison "in consideration of various circumstances".[171]

On 26 October 1792 Heywood and Morrison received royal pardons from King George III and were released. Muspratt, through his lawyer, won a stay of execution by filing a petition protesting that court martial rules had prevented his calling Norman and Byrne as witnesses in his defence.[172] He was still awaiting the outcome when Burkett, Ellison and Millward were hanged from the yardarm of HMS Brunswick in Portsmouth dock on 28 October. Some accounts claim that the condemned trio continued to protest their innocence until the last moment,[173] while others speak of their "manly firmness that ... was the admiration of all".[174] There was some unease expressed in the press—a suspicion that "money had bought the lives of some, and others fell sacrifice to their poverty."[175] A report that Heywood was heir to a large fortune was unfounded; nevertheless, Dening asserts that "in the end it was class or relations or patronage that made the difference."[175] In December Muspratt heard that he was reprieved, and on 11 February 1793 he, too, was pardoned and freed.[176]

Aftermath

Much of the court martial testimony was critical of Bligh's conduct—by the time of his return to England in August 1793, following his successful conveyance of breadfruit to the West Indies aboard Providence, professional and public opinion had turned against him.[177] He was snubbed at the Admiralty when he went to present his report, and was left on half pay for 19 months before receiving his next appointment.[178] In late 1794 the jurist Edward Christian, brother of Fletcher, published his Appendix to the court martial proceedings, which was said by the press to "palliate the behaviour of Christian and the Mutineers, and to criminate Captain Bligh".[179] Bligh's position was further undermined when the loyalist gunner Peckover confirmed that much of what was alleged in the Appendix was true.[180]

Bligh commanded HMS Director at the Battle of Camperdown in October 1797 and HMS Glatton in the Battle of Copenhagen in April 1801.[14] In 1805 while commanding HMS Warrior, he was court-martialled for using bad language to his officers, and reprimanded.[181] In 1806, he was appointed Governor of New South Wales in Australia; after two years a group of army officers arrested and deposed him in the Rum Rebellion. After his return to England, Bligh was promoted to rear-admiral in 1811 and vice-admiral in 1814, but was not offered further naval appointments. He died, aged 63, in December 1817.[14]

Of the pardoned mutineers, Heywood and Morrison returned to naval duty. Heywood acquired the patronage of Hood and, by 1803 at the age of 31, had achieved the rank of captain. After a distinguished career, he died in 1831.[177] Morrison became a master gunner, and was eventually lost in 1807 when HMS Blenheim foundered in the Indian Ocean. Muspratt is believed to have worked as a naval steward before his death, in or before 1798. The other principal participants in the court martial—Fryer, Peckover, Coleman, McIntosh and others—generally vanished from the public eye after the closing of the procedures.[182]

Pitcairn

Settlement

After leaving Tahiti on 22 September 1789, Christian sailed Bounty west in search of a safe haven. He then formed the idea of settling on Pitcairn Island, far to the east of Tahiti; the island had been reported in 1767, but its exact location was never verified. After months of searching, Christian rediscovered the island on 15 January 1790, 188 nautical miles (348 km; 216 mi) east of its recorded position.[183] This longitudinal error contributed to the mutineers' decision to settle on Pitcairn.[184]

Bounty Bay on Pitcairn Island, where HMS Bounty was burned on 23 January 1790

On arrival the ship was unloaded and stripped of most of its masts and spars, for use on the island.[180] It was set ablaze and destroyed on 23 January, either as an agreed upon precaution against discovery or as an unauthorised act by Quintal—in either case, there was now no means of escape.[185]

The island proved an ideal haven for the mutineers—uninhabited and virtually inaccessible, with plenty of food, water, and fertile land.[183] For a while, the mutineers and Tahitians existed peaceably. Christian settled down with Isabella; a son, Thursday October Christian, was born, as were other children.[186] Christian's authority as leader gradually diminished, and he became prone to long periods of brooding and introspection.[187]

Gradually, tensions and rivalries arose over the increasing extent to which the Europeans regarded the Tahitians as their property, in particular the women who, according to Alexander, were "passed around from one 'husband' to the other".[185] In September 1793 matters degenerated into extreme violence, when five of the mutineers—Christian, Williams, Martin, Mills, and Brown—were killed by Tahitians in a carefully executed series of murders. Christian was set upon while working in his fields, first shot and then butchered with an axe; his last words, supposedly, were: "Oh, dear!"[188][n 12] In-fighting continued thereafter, and by 1794 the six Tahitian men were all dead, killed either by the widows of the murdered mutineers or by each other.[190] Two of the four surviving mutineers, Young and Adams, assumed leadership and secured a tenuous calm, which was disrupted by the drunkenness of McCoy and Quintal's after the former distilled an alcoholic beverage from a local plant.[183]

Some of the women attempted to leave the island in a makeshift boat but could not launch it successfully. Life continued uneasily until McCoy's suicide in 1798. A year later, after Quintal threatened fresh murder and mayhem, Adams and Young killed him and were able to restore peace.[191]

Discovery

Parts of Bounty's rudder, recovered from Pitcairn Island and preserved in a Fiji museum

After Young succumbed to asthma in 1800, Adams took responsibility for the education and well-being of the nine remaining women and 19 children. Using the ship's Bible from Bounty, he taught literacy and Christianity, and kept peace on the island.[184] This was the situation in February 1808, when the American sealer Topaz came unexpectedly upon Pitcairn, landed, and discovered the, by then, thriving community.[192] News of Topaz's discovery did not reach Britain until 1810, when it was overlooked by an Admiralty preoccupied by war with France.

In 1814, two British warships, HMS Briton and HMS Tagus, chanced upon Pitcairn. Among those who greeted them were Thursday October Christian and George Young (Edward Young's son)[193]. The captains, Sir Thomas Staines and Philip Pipon, reported that Christian's son displayed "in his benevolent countenance, all the features of an honest English face".[194] On shore they found a population of 46 mainly young islanders led by Adams,[194] upon whom the islanders' welfare was wholly dependent, according to the captains' report.[195] After receiving Staines's and Pipon's report, the Admiralty decided to take no action.

In the following years, many ships called at Pitcairn Island and heard Adams's various stories of the foundation of the Pitcairn settlement.[195] Adams died in 1829, honoured as the founder and father of a community that became celebrated over the next century as an exemplar of Victorian morality.[183] Over the years, many recovered Bounty artefacts have been sold by islanders as souvenirs; in 1999, the Pitcairn Project was established by a consortium of Australian academic and historical bodies, to survey and document all the material remaining on-site, as part of a detailed study of the settlement's development.[196]

Cultural impact

Biographies and history

The perception of Bligh as an overbearing tyrant began with Edward Christian's Appendix of 1794.[197] Apart from Bligh's journal, the first published account of the mutiny was that of Sir John Barrow, published in 1831. Barrow was a friend of the Heywood family; his book mitigated Heywood's role while emphasising Bligh's severity.[198] The book also instigated the legend that Christian had not died on Pitcairn, but had somehow returned to England and been recognised by Heywood in Plymouth, around 1808–1809.[199] An account written in 1870 by Heywood's stepdaughter Diana Belcher further exonerated Heywood and Christian and, according to Bligh biographer Caroline Alexander, "cemented ... many falsehoods that had insinuated their way into the narrative".[198]

For public perception, Bligh was unfortunate in his timing: The story of the mutiny became public knowledge when the Romantic poets first commanded the literary scene. Bligh's chief apologist was Sir Joseph Banks, while Christian was championed by Wordsworth and Coleridge.[200]

Among historians' attempts to portray Bligh more sympathetically are those of Richard Hough (1972) and Caroline Alexander (2003). Hough depicts "an unsurpassed foul-weather commander ... I would go through hell and high water with him, but not for one day in the same ship on a calm sea".[201] Alexander presents Bligh as over-anxious, solicitous of his crew's well-being, and utterly devoted to his task, however Bligh's reputation as the archetypal bad commander remains: the Baltimore Sun's reviewer of Alexander's book wrote "poetry routed science and it has held the field ever since".[202]

Dramatic and documentary films

Poster for the 1935 film Mutiny on the Bounty, starring Charles Laughton as Bligh and Clark Gable as Christian

In addition to many books and articles about the mutiny, in the 20th century five feature films were produced. The first was a 1916 silent Australian film, subsequently lost.[203] The second, also from Australia, entitled In the Wake of the Bounty (1933), and was the screen debut of Errol Flynn in the role of Christian.[203] The impact of this film was overshadowed by that of the MGM version, Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), based on the popular namesake novel by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, and starring Charles Laughton and Clark Gable as Bligh and Christian, respectively. The film's story was presented, says Dening, as "the classic conflict between tyranny and a just cause";[204] Laughton's portrayal became in the public mind the definitive Bligh, "a byword for sadistic tyranny".[202]

The two subsequent major films, Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) with Trevor Howard and Marlon Brando, and The Bounty (1984) with Anthony Hopkins and Mel Gibson, largely perpetuated this image of Bligh and that of Christian as tragic hero. The latter film added a level of homoeroticism to the Bligh–Christian relationship.[204]

In 1998, in advance of a BBC documentary film aimed at Bligh's rehabilitation, the respective descendants of the captain and Christian feuded over their contrary versions of the truth. Dea Birkett, the programme's presenter, suggested that "Christian versus Bligh has come to represent rebellion versus authoritarianism, a life constrained versus a life of freedom, sexual repression versus sexual licence."[205]

Notes and references

Footnotes

^ James Cook commanded his first voyage in HMS Endeavour as a newly promoted lieutenant, and was not promoted to the rank of captain until after his second voyage.[5][6] However, Cook always insisted on the support of a marine detachment of at least twelve.[7]

^ The latter part of this voyage was without Cook, who was killed by Hawaiians in 1779.[12][13]

^ Dates are given as recorded by Bligh in Bounty's log (where applicable), which was kept according to the "nautical", "navy" or "sea" time then used by the Royal Navy—each day begins at noon and continues until noon the next day, twelve hours ahead of regular "civil", "natural", or "land" time. The nautical "15 October", for example, equates to the land time period between noon on the 14th and noon on the 15th.[37]

^ An early example of Bligh's esteem for Christian was indicated at Tenerife, where Bounty stopped between 5 and 11 January. On arrival, Bligh sent Christian ashore as the ship's representative to pay respect to the island's governor.[46][47]

^ This was not a formal naval promotion, but it gave Christian the authority of a full lieutenant on the voyage, and greatly increased his chances of a permanent lieutenant's commission from the Admiralty on his return.[49][50]

^ Suggestions that Bligh was an exceptionally harsh commander are not borne out by evidence. His violence was more verbal than physical;[14] as a captain, his overall flogging rate of less than one in ten seamen was exceptionally low for the time.[61] He was known for shortness of temper and sharpness of tongue, but his rages were generally directed at his officers, particularly when he perceived incompetence or dereliction of duty.[61]

^ Morrison's journal was probably written with the advantage of hindsight, after his return to London as a prisoner. Hough argues that Morrison could not have maintained a day-by-day account of all the experiences he underwent, including the mutiny, his capture, and the return to England.[81]

^ The historian Leonard Guttridge suggests that Christian's psychological state may have been further affected by the venereal disease contracted in Tahiti.[87]

^ Bligh listed these provisions in his journal as 150 pounds (68 kg) of bread, 28 gallons (130 litres) of water, 20 pounds (9.1 kg) of pork, and a few coconuts and breadfruit salvaged from Tofua. There were also three bottles of wine and five quarts of rum.[105]

^ The strait through which the loyalists passed pursued by natives is still called Bligh Water.[113]

^ Morrison and his men created a seaworthy schooner. When HMS Pandora arrived in Tahiti in March 1791 in search of mutineers, the schooner was confiscated and commandeered to act as Pandora's tender. The schooner subsequently disappeared in a storm and was presumed lost, but was returned safely to Batavia by a skeleton crew.[148]

^ This account of Christian's death was based on the account of John Adams, the last surviving mutineer. Adams was sometimes inconsistent in his stories; for example, he also claimed that Christian's death was due to suicide.[189]

References

^ Winfield 2007, p. 355.

^ Hough 1972, p. 64.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 70.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 49, 71.

^ David 2004.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 72.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 71.

^ McKinney 1999, p. 16.

^ McKinney 1999, pp. 17–20.

^ Hough 1972, p. 65.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 43.

^ ab Darby 2004.

^ McKinney 1999, pp. 7–12.

^ abcde Frost 2004.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 47.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 58–59.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 66–67.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 73.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 48.

^ ab McKinney 1999, pp. 164–166.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 51.

^ ab Hough 1972, p. 74.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 56.

^ McKinney 1999, pp. 20–22.

^ ab Hough 1972, pp. 75–76.

^ Dening 1992, p. 70.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 63–65.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 67–68.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 68.

^ McKinney 1999, p. 23.

^ McKinney 1999, pp. 17–23, 164–166; Wahlroos 1989, p. 304.

^ ab McKinney 1999, pp. 17–23, 37, 164–166.

^ Dening 1992, pp. 28–32.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 69.

^ ab Bligh 1792, pp. 158–160; Hough 1972, pp. 76–77; Alexander 2003, frontispiece.

^ Hough 1972, p. 78.

^ McKinney 1999, p. 180.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 70–71.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 72–73.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 78–80.

^ McKinney 1999, pp. 25–26.

^ McKinney 1999, pp. 13–14, 28.

^ Hough 1972, p. 83.

^ ab Hough 1972, p. 88.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 86.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 79.

^ ab Bligh 1792, p. 27.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 25.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 86–87.

^ McKinney 1999, p. 31.

^ Hough 1972, p. 87.

^ Dening 1992, p. 22.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 30.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 90.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 33.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 95–96.

^ ab Alexander 2003, pp. 92–94.

^ Dening 1992, p. 69.

^ ab Hough 1972, pp. 97–99.

^ ab Alexander 2003, pp. 97–98.

^ ab Dening 1992, p. 127.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 100–101.

^ Wahlroos 1989, pp. 297–298.

^ Dening 1992, p. 71.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 101–103.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 103–104.

^ McKinney 1999, p. 47.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 105–107.

^ Hough 1972, p. 115.

^ abc Hough 1972, pp. 122–125.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 112.

^ Guttridge 2006, p. 26.

^ Guttridge 2006, p. 24.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 162.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 102.

^ ab Alexander 2003, pp. 115–120.

^ ab Alexander 2003, pp. 124–125.

^ Hough 1972, p. 128.

^ ab Hough 1972, p. 133.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 126.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 312–313.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 131–132.

^ ab Hough 1972, pp. 135–136.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 129–130.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 138–139.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 132–133.

^ abcd Guttridge 2006, pp. 27–29.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 136.

^ Hough 1972, p. 144.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 13–14, 147.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 14–16.

^ Hough 1972, p. 148.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 17–21.

^ abcdefg Guttridge 2006, pp. 29–33.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 140.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 154.

^ ab Hough 1972, pp. 21–24.

^ Hough 1972, p. 26.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 149–151.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 158–159.

^ ab Alexander 2003, pp. 140–141.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 161–162.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 165.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 165–169.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 176.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 169–172.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 148.

^ Hough 1972, p. 175.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 186.

^ Guttridge 2006, pp. 33–35.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 150.

^ Hough 1972, p. 174.

^ Stanley 2004, pp. 597–598.

^ ab Hough 1972, p. 189.

^ Hough 1972, p. 179.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 151.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 180–182.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 200.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 184–185.

^ Guttridge 2006, p. 35.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 186–187.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 152.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 227.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 154.

^ Bligh 1792, pp. 239–240.

^ Hough 1972, p. 213.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 257.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 163–164.

^ Bligh 1792, p. 264.

^ Hough 1972, p. 215.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 12–13.

^ Guttridge 2006, p. 36.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 192–195.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 194–196.

^ ab Dening 1992, p. 90.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 196–197.

^ ab Hough 1972, pp. 199–200.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 14.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 201–203.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 15.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 250.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 368–369.

^ Dening 1992, p. 84.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 204–205.

^ ab Hough 1972, p. 229.

^ Dening 1992, pp. 215–217.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 220–221.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 10, 19, 29–30.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 8.

^ Tagart 1832, p. 83.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 216–217.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 173.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 7.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 11.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 9.

^ Dening 1992, pp. 238–239.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 226–227.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 15–18.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 227–229.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 22–26.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 227–230.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 27, 30–31.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 32–35.

^ Hough 1972, p. 218.

^ Dening 1992, pp. 43–44.

^ Hough 1972, p. 276.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 204–205.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 272.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 240–245.

^ Hough 1972, p. 281.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 283.

^ Dening 1992, p. 46.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 300–302.

^ Dening 1992, p. 48.

^ ab Dening 1992, pp. 37–42.

^ Alexander 2003, p. 302.

^ ab Hough 1972, p. 284.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 318, 379.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 340–341.

^ ab Hough 1972, p. 286.

^ Hough 1972, p. 290.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 377–378.

^ abcd Government of Pitcairn 2000.

^ ab Stanley 2004, pp. 288–296.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 369.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 243, 246.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 245–246.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 254–259.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 371–372.

^ Guttridge 2006, p. 86.

^ Hough 1972, pp. 266–267.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 347–348.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 351–352.

^ ab Barrow 1831, pp. 285–289.

^ ab Alexander 2003, p. 355.

^ Erskine 1999.

^ Alexander 2003, pp. 343–344.

^ ab Alexander 2003, pp. 401–402.

^ Barrow 1831, pp. 309–310.

^ ALAN., FROST, (2018). MUTINY, MAYHEM, MYTHOLOGY : bounty's enigmatic voyage. [S.l.]: SYDNEY UNIV PRESS. ISBN 1743325878. OCLC 1037288806..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Hough 1972, pp. 302–303.

^ ab Lewis 2003.

^ ab Dening 1992, p. 344.

^ ab Dening 1992, p. 346.

^ Minogue 1998.

Online

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Darby, Madge (2004). "Bligh, Sir Richard Rodney (1737–1821)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2648.

(subscription or UK public library membership required)

David, Andrew (2004). "Cook, James (1728–1779)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6140.

(subscription or UK public library membership required)

Erskine, Nigel (1999). "Reclaiming the Bounty". Archaeology. Boston: Archaeological Institute of America. 52 (3). Retrieved 18 May 2015.

Frost, Alan (2004). "Bligh, William (1754–1817)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2650.

(subscription or UK public library membership required)

"History of Pitcairn Island". Guide to Pitcairn. Auckland: Government of the Islands of Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno. 2000. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

Newspapers

Lewis, Mark (26 October 2003). "'The Bounty': Fletcher Christian was the villain". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

Minogue, Tim (22 March 1998). "Blighs v Christians, the 209-year feud". The Independent. London. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

Bibliography

Alexander, Caroline (2003). The Bounty. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-257221-7.

Barrow, Sir John (1831). The Eventful History of the Mutiny and Piratical Seizure of HMS Bounty: Its Causes and Consequences. London: John Murray. OCLC 4050135.

Bligh, William (1792). A Voyage to the South Sea, etc. London: Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty. OCLC 28790.

Dening, Greg (1992). Mr Bligh's Bad Language: Passion, Power and Theatre on the Bounty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38370-7.

Guttridge, Leonard F (2006) [1992]. Mutiny: A History of Naval Insurrection. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-348-2.

Hough, Richard (1972). Captain Bligh and Mr Christian: The Men and the Mutiny. London: Hutchinsons. ISBN 978-0-09-112860-9.

McKinney, Sam (1999) [1989]. Bligh!: The Whole Story of the Mutiny Aboard H.M.S. Bounty. Victoria, British Columbia: TouchWood Editions. ISBN 978-0-920663-64-6.

Stanley, David (2004). South Pacific (Eighth ed.). Chico, California: Moon Handbooks. ISBN 978-1-56691-411-6.

Tagart, Edward (1832). A Memoir of the late Captain Peter Heywood, R.N. with Extracts from his Diaries and Correspondence. London: Effingham Wilson. OCLC 7541945.

Wahlroos, Sven (1989). Mutiny and Romance in the South Seas: a Companion to the Bounty Adventure. Topsfield, Massachusetts: Salem House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-88162-395-6.

Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84415-700-6.

Further reading

Fryer, John (1979). Walters, Stephen S, ed. The Voyage of the Bounty Launch: John Fryer's Narrative. Guildford: Genesis Publications. ISBN 978-0-904351-10-1.

Morrison, James (1935). Rutter, Owen, ed. The Journal of James Morrison, etc. London: Golden Cockerel Press. OCLC 752837769.

Proud, Jodie; Zammit, Anthony (2006). "From Mutiny to Eternity: The Conservation of Lt. William Bligh's Bounty Logbooks" (PDF). Canberra: Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material. Retrieved 1 May 2015.