Eufaula, Alabama

Eufaula, Alabama | |

|---|---|

City | |

The MacMonnies Fountain in downtown Eufaula. | |

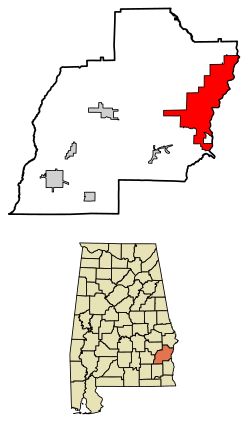

Location of Eufaula in Barbour County, Alabama. | |

| Coordinates: 31°53′21″N 85°9′13″W / 31.88917°N 85.15361°W / 31.88917; -85.15361 | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alabama |

| County | Barbour |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jack Tibbs |

| Area [1] | |

| • Total | 73.47 sq mi (190.30 km2) |

| • Land | 59.52 sq mi (154.14 km2) |

| • Water | 13.96 sq mi (36.16 km2) |

| Elevation | 262 ft (80 m) |

| Population (2010)[2] | |

| • Total | 13,137 |

| • Estimate (2017)[3] | 12,044 |

| • Density | 202.37/sq mi (78.14/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 36027, 36072 |

| Area code(s) | 334 |

| FIPS code | 01-24568 |

GNIS feature ID | 0118051 |

| Website | http://www.eufaulaalabama.com/ |

Eufaula is the largest city in Barbour County, Alabama, United States. As of the 2010 census the city's population was 13,137.

Contents

1 History

1.1 The Civil War in Eufaula

1.2 Reconstruction in Eufaula

1.2.1 Eufaula Baptists during reconstruction

1.3 Civil rights years

1.3.1 Eufaula housing case

1.3.2 Voting Rights Act of 1965

1.3.3 School integration

1.4 Other recent history

2 Geography

3 Climate

4 Demographics

5 Education

6 Culture and recreation

6.1 Historic buildings

6.2 Sports

6.3 Movie location

6.4 Tree That Owns Itself

7 Notable people

8 Gallery

9 References

10 Literature

11 External links

History

Slaves worth $150,000 to be purchased for construction of railroad (Daily Confederation, November 10, 1859)

The site along the Chattahoochee River that is now modern-day Eufaula was occupied by three Creek tribes, including the Eufaulas.[4]:3 By the 1820s the land was part of the Creek Indian Territory and supposedly off-limits to white settlement.[4]:4 By 1827 enough illegal white settlement had occurred that the Creeks appealed to the federal government for protection of their property rights. In July of that year, federal troops were sent to the Eufaula area to remove the settlers by force of arms, a conflict known as the "Intruders War".[4]:4

The Creeks signed the Treaty of Washington in 1826, ceding most of their land in Georgia and eastern Alabama to the United States,[5] but it was not fully effective in practice until the late 1820s. The 1832 Treaty of Cusseta, by which the Creeks ceded all land east of the Mississippi River to the United States, allowed white settlers to legally buy land from the Creek. However, the treaty's terms did not require any natives to relocate.[6] By 1835 the land on which the town was built had been mostly purchased by white settlers, and had a store, owned in part by William Irwin, after whom the new settlement was named "Irwinton".[4]:5

Significant numbers of Jewish settlers came to Eufaula in the middle of the nineteenth century from Germany and from neighboring states. The community founded a cemetery; the first burial took place in 1845.[7]

By the mid 1830s downtown Irwinton was platted out and development was well underway.[4]:9–16 Much of its historic character has been preserved and is now known as the Seth Lore and Irwinton Historic District. In 1842[4]:18 or 1843[8]:18 Irwinton was renamed "Eufaula", possibly[8]:18 to end postal confusion ensuing from its proximity to Irwinton, Georgia.[4]:18 The town was officially incorporated under that name in 1857.[9]:10

In 1850 secessionists in the town formed a vigilante committee which terrorized any white people who had abolitionist sympathies. Thus captain Elisha Bett was driven from the town and only returned after he had signed a written agreement not to express his views again.[10]

By the late 1850s, Eufaula's advantageous location on the Chattahoochee made it a major shipping center for cargo bound for the Port of Apalachicola and, from there, to major world markets such as Liverpool and New York City.[8]:19 By this time, planning for the Montgomery and Eufaula Railroad, which was to include a new bridge over the Chattahoochee, was well underway.[11] By November 1859 the railroad company authorized its president to purchase slaves worth $150,000 to use for the construction of the railroad.[12] Grading for the track bed began in January 1860.[13] By 1861, when it had become clear that the American Civil War was imminent, work on the railroad was suspended to allow the laborers to lay track between Montgomery, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida, to facilitate the transport of Confederate troops to the Gulf of Mexico.[14] Work on the railroad was resumed after the war, and, in October 1871, the tracks finally reached the city limits of Eufaula and a depot agent, John O. Martin, was appointed to run that terminal station.[15]

The Civil War in Eufaula

Very little is known about the history of Eufaula during the American Civil War because very few contemporary records or newspapers survive.[8]:10 Alabama seceded from the United States on January 11, 1861. By the end of the month a military encampment was founded at Eufaula with soldiers ready to decamp to Fort Pickens or elsewhere as needed at the onset of hostilities.[16] Ultimately six companies of the Confederate States Army (CSA) were raised at Eufaula and Barbour County. One of these was the Eufaula Zouaves, one of dozens of military units on both sides that adopted that name, patterning their uniforms and order of battle after the French light infantry units on which they were modeled.[17]

The CSA operated a military hospital in Eufaula during the conflict.[18] Eufaula's strategic position on the Chattahoochee river involved it in the naval component of the Confederate war effort, and at least one ironclad warship was constructed in the city.[19] By April 1865, the Union Army had occupied Selma, Alabama, and plans were made to move the Alabama state government to Eufaula should Montgomery fall to Federal troops.[20]

Montgomery was captured on April 12 and governor Thomas H. Watts, with other state officials, fled to Eufaula,[21] establishing what the New York Daily Tribune called "the fugitive seat of Government of Alabama".[22] On April 29, 1865, Union general Benjamin Grierson had reached Clayton, Alabama, and word had finally made it to Eufaula that the war was over.[9]:183 The mayor of Eufaula and some members of the city council rode over to Clayton to escort Grierson into Eufaula, thus ensuring a generally peaceful transition to Federal control of the city.[9]:183

Eufaula was the site of what may have been the last battle of the Civil War. On May 19, 1865, at Hobdy's Bridge near Eufaula a Confederate detachment attacked a 44 man detachment from companies C and F the Union's 1st Florida Cavalry Regiment, resulting in one soldier killed and three wounded. [23]

By May 1865 the Daily Intelligencer of Atlanta reported that 10,000 Union troops had occupied Eufaula.[24] In the immediate aftermath of the occupation there was a food riot and an "attempt to illegally distribute the public stores".[25] By the end of May Eufaula was sufficiently pacified that a special agent of the United States Post Office was able to deliver mail from Providence, Rhode Island, to the town via Macon, Georgia, without need for any of the twenty-five armed guards he had brought with him to defend him with violence.[26]

Reconstruction in Eufaula

By August 1865 cotton shipping out of Eufaula was increasing again, mostly in barter for household goods, which were arriving by ship in increasing quantities.[27] However, the quantity of cotton being shipped out was nowhere near antebellum levels, and ships bound for Apalachicola were far below capacity.[28] In November 1865 the Federal garrison that had been occupying Eufaula was relieved of duty by two companies of the 8th Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment, whose commander, John Bell, assured the citizens that they would not "be disturbed in their lawful business."[29]

In March 1867, the United States Congress passed the first of four Reconstruction Acts and the Reconstruction Era began in earnest. Alabama, and therefore Eufaula, was placed in the Third Military District under the command of General John Pope. By the time the first elections were held under the new regime, in October 1867, Barbour County had about 5,000 registered voters, with about 1,500 white and 3,500 black.[30]

Municipal elections were held in March 1870 and white candidates won all offices except for the two fourth (of four) ward positions as aldermen, which were won by black candidates Washington Burke and Melvin Patterson.[31] Election officials set aside Burke's and Patterson's victories for election fraud and replaced them with their white competitors R. A. Solo and T. E. Morgan as fourth ward aldermen.[32] In the same election a radical republican candidate named Keills won the post of City Court Judge.[33] According to the Mobile Register, Keills's "election turned upon sectional differences. The negroes made their usual noisy demonstrations, marching in from the country with fife and drum."[33]

In 1874, members of the White League instigated the Election Riot of 1874 in Eufaula, killing at least 7 black Republicans, injuring at least 70 more, and prevented over 1,000 others from voting.

Eufaula Baptists during reconstruction

Prior to the Civil War both black and white Southern Baptists had worshipped in the same churches. By 1866 there was a general movement of black Baptists to separate from the white churches and form their own congregations. This process went smoothly in Eufaula, with black Baptists applying to the integrated church for permission to separate in May 1866. The permission was granted, and, after negotiations, the black Baptists were allowed to purchase an old church building to house their own congregation.[34] This congregation formed the basis of the Eufaula Association, one of two black Baptist associations formed in Alabama prior to the founding of the state association of black Baptist churches in 1868.[35] By 1869 the site for the new white First Baptist Church of Eufaula had been purchased and $16,000 out of an estimated $25,000 necessary for its construction had been raised.[36]

Civil rights years

Eufaula housing case

For a number of years after the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 decision Brown v. Board of Education, which overturned Plessy v. Ferguson by declaring racial segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional, the schools in Eufaula remained unintegrated.[37] In 1955 the Eufaula Housing Authority sought to use eminent domain to condemn land on which a number of black families had lived since emancipation in order to build public housing, a park, and an expansion of the white high school.[38] The residents of the neighborhood, surrounded on all sides by white areas, thought that the city's motive was actually to keep their children out of a newly built high school once the now-inevitable racial integration occurred.[37]

In 1958 civil rights attorneys Fred Gray and Constance Baker Motley filed a suit in the U.S. District court claiming that their clients' constitutional rights were being violated by the plan.[37] The federal case was dismissed, but Gray (now appearing without Motley)[37] appealed to the Alabama Circuit Court, where the case was heard by then-judge George Wallace.[39] As before, Gray claimed that since the new development would allow white residents only, their civil rights were being violated by the City.[39] Although his appeal of the constitutional issue was unsuccessful, Gray also appealed the city's valuations of his clients' properties and, arguing before all-white juries in Wallace's court, managed in most of the cases to win much higher prices.[37]

Voting Rights Act of 1965

After the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 the United States Department of Justice sent federal observers into 24 southern counties to enforce its provisions regarding voter registration for the Fall 1965 elections. Many of these counties saw a significant increase in black registration, but Eufaula, not having federal supervision, had comparatively low rates. For instance, on August 16, 1965, 600 black citizens waited in line at the County courthouse in Eufaula to register, but by the time the office closed, only 265 had managed to fill out the paperwork.[40]

In 1966 the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) responded by appointing a local Eufaulan, Daddy Bone, to organize voter registration drives in Eufaula. Bone initiated a series of nonviolent protests and boycotts of local stores that refused to hire blacks which attracted SNCC supporters from around the Southeastern United States. The city of Eufaula, under some pressure from the businessmen whose stores were targeted, passed anti-picketing laws and began arresting demonstrators en masse for violating them. Bone brought in civil rights lawyer S. S. Seay to defend the protestors, who were mostly convicted, and in such numbers as to overwhelm the county jail.[41]

School integration

In July 1968 the United States Department of Justice filed suit against 76 Alabama school districts, including that of Eufaula, in an attempt to bring them into compliance with Brown v. Board of Education.[42]

Schools in Eufaula remained segregated by race until the fall of 1966 and the first blacks graduated with the senior class of 1967.[43] After integration began the school stopped sponsoring social events, such as proms[43] although unofficial segregated events were still held. By 1990, students at Eufaula High School had begun pressuring school officials to allow them to hold integrated proms, and the first such was held in 1991 without incident.[43]

Other recent history

In 1963, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers created Walter F. George Lake (unofficially named Lake Eufaula) behind the lock and dam of Fort Gaines, Georgia, once again assuring Eufaula's importance as an inland port.

In the early 1960s, the United States Coast Guard set up an Aids to Navigation Team in Eufaula that is still active today servicing from Columbus, Georgia, to Apalachicola, Florida, and the Flint River.

In 1964, the Eufaula National Wildlife Refuge was established along Lake Walter F. George to serve and protect many endangered and threatened species such as the American bald eagle, the American alligator, the wood stork and the peregrine falcon. The refuge is a major tourist attraction for visitors from around the country.

On March 3, 2019, a tornado hit the city as part of a larger tornado outbreak.[44]

Geography

Eufaula is located at 31°53'21.732" North, 85°9'13.586" West (31.889370, -85.153774).[45] The city is located along U.S. Highways 82 and 431 in southeast Alabama on the Georgia state line, adjacent to the city of Georgetown, Georgia, which is east, across the Chattahoochee River, from the city. Eufaula is located 75 mi (121 km) southeast of Montgomery, 40 mi (64 km) southwest of Columbus, Georgia and 48 mi (77 km) northeast of Dothan.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 73.5 square miles (190 km2), of which 59.4 square miles (154 km2) is land and 14.1 square miles (37 km2) (19.13%) is water. It sits on a reservoir called Walter F. George Lake, or Lake Eufaula to locals.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Eufaula has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[46]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 3,000 | — | |

| 1870 | 3,185 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,836 | 20.4% | |

| 1890 | 4,394 | 14.5% | |

| 1900 | 4,532 | 3.1% | |

| 1910 | 4,259 | −6.0% | |

| 1920 | 4,939 | 16.0% | |

| 1930 | 5,208 | 5.4% | |

| 1940 | 6,269 | 20.4% | |

| 1950 | 6,906 | 10.2% | |

| 1960 | 8,357 | 21.0% | |

| 1970 | 9,102 | 8.9% | |

| 1980 | 12,097 | 32.9% | |

| 1990 | 13,220 | 9.3% | |

| 2000 | 13,908 | 5.2% | |

| 2010 | 13,137 | −5.5% | |

| Est. 2017 | 12,044 | [3] | −8.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[47] 2013 Estimate[48] | |||

As of the census[49] of 2010, there were 13,137 people, 5,237 households, and 3,630 families residing in the city. There were 5,829 housing units at an average density of 79.3 per square mile (30.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 51.0% White, 44.6% Black or African American, 0.5% Native American, 0.6% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 2.2% from other races, and 0.9% from two or more races. 4.3% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 5,237 households out of which 30.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.6% were married couples living together, 22.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.7% were non-families. 28.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.01.

In the city, the population's age was spread out with 26.1% under the age of 18, 8.6% from 18 to 24, 22.7% from 25 to 44, 27.0% from 45 to 64, and 15.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.9 years. For every 100 females, there were 86.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 84.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $34,025, and the median income for a family was $44,234. Males had a median income of $37,985 versus $23,890 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,515. About 18.0% of families and 23.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 32.8% of those under age 18 and 20.7% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Advertisement in the Charleston Courier seeking superintendent for newly opened Eufaula Female Academy; June 18, 1844

Eufaula is served by Eufaula City Schools which has two elementary schools. It has a middle school, Admiral Moorer Middle School, named after Admiral Thomas Hinman Moorer. The local high school is Eufaula High School and their mascot is a tiger. It is also served by a private accredited school, Lakeside School. The Lakeside athletic teams are known as the Chiefs. Eufaula is served as well as a smaller unaccredited school, Parkview Christian School. It was at one time home to the Eufaula Female Academy, a female seminary founded in 1844.

Culture and recreation

Historic buildings

Many of Eufaula's historic buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[50] Other historic buildings include the Eufaula First United Methodist Church and the First Baptist Church of Eufaula. The Seth Lore and Irwinton Historic District, with 667 contributing properties, is the second-largest historic district in Alabama.[50][51]

The Shorter Mansion was built in 1884 by Eli Shorter and is recognized by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The bottom floor is often host to many receptions and events, while the second floor serves as a museum honoring the six Alabama governors from Barbour County, as well as Admiral Thomas Moorer, a former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[50][52]

Fendall Hall, built from 1856 to 1860, is an Italianate-style historic house museum that is owned and operated by the Alabama Historical Commission.[50][53]

Sports

Lake Eufaula is known as the "Big Bass Capital of the World".[54]

Eufaula was home to a minor league baseball team, the Eufaula Millers, in 1952 and 1953.

Movie location

In the 2002 film Sweet Home Alabama, the historic homes shown in Melanie's (Reese Witherspoon) return to Pigeon Creek were shot in Eufaula.

Tree That Owns Itself

The Tree That Owns Itself is an oak tree in Eufaula that has been replaced several times. It was given the ownership of its land by the governor in 1936, with each of the two replacements receiving the ownership to the land too. Confederate soldier Captain John A. Walker previously owned the land. [55][56]

Notable people

Alpheus Baker, brigadier general in the Confederate States Army[57]

Peyton Brown, model and Miss Alabama USA 2016[58]

Daryon Brutley, former professional football defensive back

Edward Bullock, Confederate officer and two-term Alabama state senator

Frank Clark, former member of the U.S. House of Representatives

James S. Clark, speaker of the Alabama House of Representatives from 1987 to 1999

S. Hubert Dent Jr., U.S. representative from 1909 to 1921

Mike Hamrick, architect of the American Village

Lula Mae Hardaway, mother of entertainer Stevie Wonder[59]

William Henry Harrison Hart, African American attorney

Bertha "B" Holt (born August 16, 1916), representative in the North Carolina General Assembly

Jerrel Jernigan, professional football player- Lawrence H Johnson Jr., US Army lieutenant colonel, commanded 7th Squadron, 17th Cavalry (Air) during 1968 Tet Offensive; unit decimated NVA at Dak To and Kontum; awarded three Distinguished Flying Crosses, a squadron Presidential Unit Citation and two Valorous Unit Awards[60][61]

Walter Kehoe, U.S. representative from Florida from 1917 to 1919

Reuben Kolb, Alabama politician

Charles S. McDowell, tenth lieutenant governor of Alabama

Thomas Hinman Moorer, chief of Naval Operations and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Martha Reeves, Motown singer, Martha Reeves and the Vandellas, and Detroit city councilwoman

Walter Reeves (born December 15, 1965), professional football player

Cody Sanders, White House staffer under President Donald J. Trump[62]

Eli Sims Shorter, U.S. representative from 1855 to 1859

John Gill Shorter, 17th Governor of Alabama[4]:16

Les Snead, general manager of the NFL Los Angeles Rams

Courtney Upshaw, professional football player

George Wallace Jr., former Alabama public service commissioner and state treasurer

Dave Watson, former professional football offensive lineman

Edwin "Pa" Watson, U.S. Army major general, friend and senior aide to President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Xavier Woodson-Luster, professional football player

Hunter Wyatt-Brown, former bishop of Episcopal Diocese of Harrisburg (Central Pennsylvania)

Gallery

Reeves Peanut Company, the Renaissance Revival-style warehouse was built by the Eufaula Grocery Company in 1903.

Eufaula post office (ZIP Code: 36027)

The Walter F. George lock and dam which creates Lake Eufaula.

Christie Pappas Building at E. Broad Street.

Fendall Hall, built from 1856 to 1860, is an Italianate-style historic house museum that is owned and operated by the Alabama Historical Commission.[50][53] It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 28, 1970.

The Tavern was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 6, 1970.

The Bray-Barron House was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 27, 1971.

The Lewis Llewellyn Cato House was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 27, 1971.

Built in 1837, Sheppard Cottage is the oldest known residence in Eufaula. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 27, 1971.

The McNab Bank Building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 24, 1971.

The Wellborn-Thomas House was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 14, 1971.

Kendall Manor was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 14, 1972.

The Shorter Mansion was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 14, 1972.

The Drewry-Mitchell-Moorer House was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 13, 1972.

The Sparks-Irby House was the home of the 44th Alabama Governor, Chauncey Sparks and his sister, Mrs. Louise Sparks Flewellen. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 28, 1972.

The Seth Lore and Irwinton Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 12, 1973.

The Kiels-McNab House was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 21, 1982.

First Presbyterian Church, completed in 1869.

The Eufaula Carnegie Library, built in 1904.

This statue of a WWI doughboy, with his arm outstretched, honors the men from Eufaula who perished in the war. It was erected and dedicated in 1920.

References

^ "2017 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jul 7, 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

^ ab "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 24, 2018.

^ abcdefgh J. A. B. Besson (1875). History of Eufaula, Alabama: The Bluff City of the Chattahoochee. Franklin Steam Print. House.

^ Francis Paul Prucha (1997). American Indian Treatires: The History of a Political Anomaly. University of California Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-520-20895-1.

^ Herbert James Lewis (2 March 2013). Clearing the Thickets: A History of Antebellum Alabama. Quid Pro Books. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-61027-166-0.

^ "Eufaula, Alabama". Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

^ abcd Mike Bunn (2013). Civil War Eufaula. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-62619-244-7.

^ abc David Williams (15 March 2011). Rich Man's War: Class, Caste, and Confederate Defeat in the Lower Chattahoochee Valley. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-4079-1.

^ Rachleff, Marshall (1981). "An Abolitionist Letter to Governor Henry W. Collier of Alabama: The Emergence of "The Crisis of Fear" in Alabama". The Journal of Negro History. 66 (3): 246–253. doi:10.2307/2716919. JSTOR 2716919.

^ "Eufaula Railroad". Daily Columbus Enquirer. October 26, 1859. p. 2.

^ "Montgomery and Eufaula Rail Road". The Daily Confederation. November 10, 1859. p. 3.

^ "Montgomery and Eufaula Railroad". Daily Columbus Enquirer. January 9, 1860. p. 2.

^ "Speedy Completion of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad". The Daily True Delta. April 6, 1861. p. 2.

^ "Montgomery and Eufaula Railroad". Daily Columbus Enquirer. Columbus, Georgia. October 15, 1871. p. 3.

^ "Alabama Military". The Macon Daily Telegraph. January 28, 1861. p. 1.

^ Terry L. Jones (15 July 2011). Historical Dictionary of the Civil War. Scarecrow Press. p. 1657. ISBN 978-0-8108-7953-9.

^ Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein (1 April 2008). The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine. M.E. Sharpe. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-7656-3078-0.

^ "Intelligence; Richmond; Eufaula". New London Daily Chronicle. October 16, 1863. p. 2.

^ "From Alabama". Augusta Chronicle. Augusta, Georgia. April 9, 1865. p. 2.

^ "From Alabama". Augusta Chronicle. Augusta, Georgia. April 16, 1865. p. 2.

^ "From Alabama March Through the Country-Conduct of the Slaves-Cruelty of Masters". New York Daily Tribune. June 3, 1865. p. 3.

^ "Skirmish at Hobdy's Bridge - Pike and Barbour Counties, Alabama". ExploreSouthernHistory.com. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

^ "Yankee; Eufaula; Alabama; Grierson". The Daily Evening News. Macon, Georgia. May 4, 1865. p. 2.

^ "Eufaula; Jasper Sawyers; Capt. Frank Brady". The Macon Daily Telegraph. Macon, Georgia. May 24, 1865. p. 2.

^ "Another Evidence of Peace". Providence Evening Press. Providence, Rhode Island. May 30, 1865. p. 3.

^ "Business at Eufaula". The Macon Daily Telegraph. Macon, Georgia. August 4, 1865. p. 2.

^ "Shipping on the Chattahooches". Daily Constitutionalist. Augusta, Georgia. August 9, 1865. p. 4.

^ "Another Garrison at Eufaula". The Daily Sun. Columbus, Georgia. December 1, 1865. p. 2.

^ "The First Day's Election Under the 'Military Bills' in Alabama". New York Herald. October 13, 1867. p. 7.

^ "From Eufaula". Georgia Daily Telegraph. Macon, Georgia. March 8, 1870. p. 3.

^ "Eufaula". The Daily Sun. Columbus, Georgia. March 8, 1870. p. 2.

^ ab "Latest by Mail". Mobile Register. Mobile, Alabama. March 13, 1870. p. 1.

^ Wayne Flynt (1998). Alabama Baptists: Southern Baptists in the Heart of Dixie. University of Alabama Press. pp. 138–9. ISBN 978-0-8173-0927-5.

^ Wilson Fallin (17 August 2007). Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama. University of Alabama Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8173-1569-6.

^ "A Flying Visit to Eufaula". Georgia Weekly Telegraph. Macon, Georgia. April 9, 1869. p. 4.

^ abcde Fred D. Gray (1 October 2012). Bus Ride to Justice: Changing the System by the System : the Life and Works of Fred Gray, Preacher, Attorney, Politician. NewSouth Books. pp. 131–9. ISBN 978-1-58838-286-3.

^ "Suit Claims Segregation In Housing". Times Daily. June 10, 1958.

^ ab "Negro Requests White Residence". The Tuscaloosa News. October 21, 1958.

^ Adam Fairclough (2001). To Redeem the Soul of America: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Martin Luther King, Jr. University of Georgia Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-8203-2346-6.

^ Solomon Seay, Jr. (1 December 2011). Jim Crow and Me: Stories from My Life as a Civil Rights Lawyer. NewSouth Books. pp. 63–6. ISBN 978-1-60306-142-1.

^ "Area Schools Named in Suit". Gadsden Times. July 15, 1968.

^ abc "No Incidents at School's First Integrated Prom". The Tuscaloosa News. May 22, 1991.

^ "Tornado causes major damage to Eufaula airport, industrial park; no injuries reported". Eufaula Tribune. March 3, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

^ Climate Summary for Eufaula, Alabama

^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013". Retrieved June 3, 2014.

^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

^ abcde National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

^ "Visitor Information - Attractions". City of Eufaula, Alabama. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

^ "The Shorter Mansion". Eufaula Heritage Association.

^ ab "Fendall Hall". Alabama Historic Commission. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

^ "Fish and Fishing in Lake Eufaula". Outdoor Alabama.

^ "An oak tree in Eufaula, Alabama officially owns itself – here is why – Alabama Pioneers". www.alabamapioneers.com. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

^ "The Tree That Owns Itself". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

^ John D. Wright (2013). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Civil War Era Biographies. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-415-87803-6.

^ Amber Sutton, Peyton Brown, of Eufaula, crowned Miss Alabama USA 2016, AL.com, November 7, 2015, Retrieved November 8, 2015

^ "Lula Mae Hardaway, 76, Stevie Wonder's Mother, Dies". The New York Times. 9 June 2006. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

^ Starry, Donn A. (1978). Mounted combat in Vietnam. Department of the Armies. p. 232.

^ Lawrence H. Johnson III (2001). Winged Sabers: The Air Cavalry in Vietnam. Stackpole Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-0811729888.

^ "From Eufaula to the White House - Alumni Spotlight with Cody Sanders". (September 12, 2018). Auburn University College of Liberal Arts. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

Literature

- Alsobrook, David Ernest. Southside: Eufaula's Cotton Mill Village and its People, 1890-1945. Mercer University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eufaula, Alabama. |

- City Webpage

- Eufaula Police Webpage

- Eufaula Pilgrimage

- Eufaula City Schools

- Eufaula Tribune

- Cato-Thorne House

Coordinates: 31°53′22″N 85°09′14″W / 31.88937°N 85.153774°W / 31.88937; -85.153774