Satsuma Rebellion

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (August 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Satsuma Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

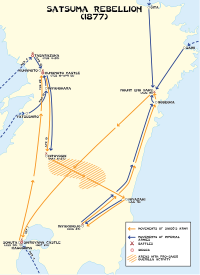

Map of the campaign | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

Meiji Emperor Prince Arisugawa Taruhito Kawamura Sumiyoshi Yamagata Aritomo | Saigō Takamori † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

100,000 | 25,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,000 dead[2] 11,000 wounded[1] About 4,000 surrendered or deserted | ||||||

Saigō Takamori (seated, in French uniform), surrounded by his officers, in traditional attire. News article in Le Monde illustré, 1877

The Satsuma Rebellion or Seinan War (Japanese: 西南戦争, Hepburn: Seinan Sensō, lit. "Southwestern War") was a revolt of disaffected samurai against the new imperial government, nine years into the Meiji Era. Its name comes from the Satsuma Domain, which had been influential in the Restoration and became home to unemployed samurai after military reforms rendered their status obsolete. The rebellion lasted from January 29, 1877, until September of that year, when it was decisively crushed and its leader, Saigō Takamori, committed seppuku after being mortally wounded.

Saigō's rebellion was the last and most serious of a series of armed uprisings against the new government of the Empire of Japan, the predecessor state to modern Japan.

Contents

1 Background

2 Prelude

3 The Southwest War

3.1 Siege of Kumamoto Castle

3.2 Battle of Tabaruzaka

3.3 Retreat from Kumamoto

3.4 Battle of Shiroyama

4 Aftermath

5 Order of battle

5.1 Organization of the Imperial Forces

5.2 Organization of the Satsuma forces

6 Name

7 See also

8 Notes

9 Bibliography

10 External links

Background

Although Satsuma had been one of the key players in the Meiji Restoration and the Boshin War, and although many men from Satsuma had risen to influential positions in the new Meiji government, there was growing dissatisfaction with the direction the country was taking. The modernization of the country meant the abolition of the privileged social status of the samurai class, and had undermined their financial position. The very rapid and massive changes to Japanese culture, language, dress and society appeared to many samurai to be a betrayal of the jōi ("expel the barbarian") portion of the sonnō jōi justification used to overthrow the former Tokugawa shogunate.

Saigō Takamori, one of the senior Satsuma leaders in the Meiji government who had supported the reforms in the beginning, was especially concerned about growing political corruption (the slogan of his rebel movement was shinsei-kōtoku (新政厚徳, new government, high morality). Saigō was a strong proponent of war with Korea in the Seikanron debate of 1873. At one point, he offered to visit Korea in person and to provoke a casus belli by behaving in such an insulting manner that the Koreans would be forced to kill him. Saigō expected both that a war would ultimately be successful for Japan and also that the initial stages of it would offer a means by which the samurai whose cause he championed could find meaningful and beneficial death. When the plan was rejected, Saigō resigned from all of his government positions in protest and returned to his hometown of Kagoshima, as did many other Satsuma ex-samurai in the military and police forces.

Imperial Japanese Army officers of the Kumamoto garrison, who resisted Saigō Takamori's siege, 1877

To help support and employ these men, in 1874 Saigō established a private academy in Kagoshima. Soon 132 branches were established all over the prefecture. The “training” provided was not purely academic: although the Chinese classics were taught, all students were required to take part in weapons training and instruction in tactics. Saigō also started an artillery school. The schools resembled paramilitary political organizations more than anything else, and they enjoyed the support of the governor of Satsuma, who appointed disaffected samurai to political offices, where they came to dominate the Kagoshima government. Support for Saigō was so strong that Satsuma had effectively seceded from the central government by the end of 1876.[3]

Prelude

Word of Saigō’s academies was greeted with considerable concern in Tokyo. The government had just dealt with several small but violent samurai revolts in Kyūshū, and the prospect of the numerous and fierce Satsuma samurai, being led in rebellion by the famous and popular Saigō was alarming.

In December 1876, the Meiji government sent a police officer named Nakahara Hisao and 57 other men to investigate reports of subversive activities and unrest. The men were captured, and under torture, confessed that they were spies who had been sent to assassinate Saigō. Although Nakahara later repudiated the confession, it was widely believed in Satsuma and was used as justification by the disaffected samurai that a rebellion was necessary in order to "protect Saigō".

Fearing a rebellion, the Meiji government sent a warship to Kagoshima to remove the weapons stockpiled at the Kagoshima arsenal on January 30, 1877. This provoked open conflict, although with the elimination of samurai rice stipends in 1877, tensions were already extremely high. Outraged by the government's tactics, 50 students from Saigō’s academy attacked the Somuta Arsenal and carried off weapons. Over the next three days, more than 1000 students staged raids on the naval yards and other arsenals.

Presented with this sudden success, the greatly dismayed Saigō was reluctantly persuaded to come out of his semi-retirement to lead the rebellion against the central government.

The clash at Kagoshima

In February 1877, the Meiji government dispatched Hayashi Tomoyuki, an official with the Home Ministry with Admiral Kawamura Sumiyoshi in the warship Takao to ascertain the situation. Satsuma governor, Oyama Tsunayoshi, explained that the uprising was in response to the government's assassination attempt on Saigō, and asked that Admiral Kawamura (Saigō's cousin) come ashore to help calm the situation. After Oyama departed, a flotilla of small ships filled with armed men attempted to board Takao by force, but were repelled. The following day, Hayashi declared to Oyama that he could not permit Kawamura to go ashore when the situation was so unsettled, and that the attack on Takao constituted an act of lèse-majesté.

Imperial troops embarking at Yokohama to fight the Satsuma rebellion in 1877.

On his return to Kobe on February 12, Hayashi met with General Yamagata Aritomo and Itō Hirobumi, and it was decided that the Imperial Japanese Army would need to be sent to Kagoshima to prevent the revolt from spreading to other areas of the country sympathetic to Saigō. On the same day, Saigō met with his lieutenants Kirino Toshiaki and Shinohara Kunimoto and announced his intention of marching to Tokyo to ask questions of the government. Rejecting large numbers of volunteers, he made no attempt to contact any of the other domains for support, and no troops were left at Kagoshima to secure his base against an attack. To aid in the air of legality, Saigō wore his army uniform. Marching north, his army was hampered by the deepest snowfall Satsuma had seen in more than 50 years, which, because of the similarity to the weather that had greeted those setting out to enact the Meiji Restoration nine years earlier, was interpreted by some as a sign of divine support.

The Southwest War

Siege of Kumamoto Castle

The Satsuma vanguard crossed into Kumamoto Prefecture on February 14. The Commandant of Kumamoto Castle, Major General Tani Tateki had 3,800 soldiers and 600 policemen at his disposal. However, most of the garrison was from Kyūshū, while a significant number of officers were natives of Kagoshima; their loyalties were open to question. Rather than risk desertions or defections, Tani decided to stand on the defensive.

On February 19, the first shots of the war were fired as the defenders of Kumamoto castle opened fire on Satsuma units attempting to force their way into the castle. Kumamoto castle, built in 1598, was among the strongest in Japan, but Saigō was confident that his forces would be more than a match for Tani's peasant conscripts, who were still demoralized by the recent Shinpūren rebellion.

On February 22, the main Satsuma army arrived and attacked Kumamoto castle in a pincer movement. Fighting continued into the night. Imperial forces fell back, and Acting Major Nogi Maresuke of the Kokura Fourteenth Regiment lost the regimental colors in fierce fighting. However, despite their successes, the Satsuma army failed to take the castle, and began to realize that the conscript army was not as ineffective as first assumed. After two days of fruitless attack, the Satsuma forces dug into the rock-hard icy ground around the castle and tried to starve the garrison out in a siege. The situation was especially desperate for the defenders as their stores of food and ammunition had been depleted by a warehouse fire shortly before the rebellion began.

During the siege, many Kumamoto ex-samurai flocked to Saigō's banner, swelling his forces to around 20,000 men. In the meantime, on March 9 Saigō, Kirino, and Shinohara were stripped of their court ranks and titles.

On the night of April 8, a force from Kumamoto castle made a sortie, forcing open a hole in the Satsuma lines and enabling desperately needed supplies to reach the garrison. The main Imperial Army, under General Kuroda Kiyotaka with the assistance of General Yamakawa Hiroshi arrived in Kumamoto on April 12, putting the now heavily outnumbered Satsuma forces to flight.

Battle of Tabaruzaka

On March 4 Imperial Army General Yamagata ordered a frontal assault from Tabaruzaka, guarding the approaches to Kumamoto, which developed into an eight-day-long battle. Tabaruzaka was held by some 15,000 samurai from Satsuma, Kumamoto and Hitoyoshi against the Imperial Army's 9th Infantry Brigade (some 90,000 men).

At the height of the battle, Saigō wrote a private letter to Prince Arisugawa, restating his reasons for going to Tokyo. His letter indicated that he was not committed to rebellion and sought a peaceful settlement. The government, however, refused to negotiate.

In order to cut Saigō off from his base, an imperial force with three warships, 500 policemen and several companies of infantry, landed in Kagoshima on March 8, seized arsenals and took the Satsuma governor into custody.

Yamagata also landed a detachment with two infantry brigades and 1,200 policemen behind the rebel lines, so as to fall on them from the rear from Yatsushiro Bay. Imperial forces landed with few losses, then pushed north seizing the city of Miyanohara on March 19. After receiving reinforcements, the imperial force, now totaling 4,000 men, attacked the rear elements of the Satsuma army and drove them back.

Tabaruzaka was one of the most intense campaigns of the war. Imperial forces emerged victorious, but with heavy casualties on both sides. Each side had suffered more than 4,000 killed or wounded.

Retreat from Kumamoto

After his failure to take Kumamoto, Saigō led his followers on a seven-day march to Hitoyoshi. Morale was extremely low, and lacking any strategy, the Satsuma forces dug in to wait for the next Imperial Army offensive. However, the Imperial Army was likewise depleted, and fighting was suspended for several weeks to permit reinforcement. When the offensive was resumed, Saigo retreated to Miyazaki, leaving behind numerous pockets of samurai in the hills to conduct guerilla attacks.

On July 24, the Imperial Army forced Saigō out of Miyakonojō, followed by Nobeoka. Troops were landed at Ōita and Saiki north of Saigō's army, and Saigō was caught in a pincer attack. However, the Satsuma army was able to cut its way free from encirclement. By August 17, the Satsuma army had been reduced to 3000 combatants, and had lost most of its modern firearms and all of its artillery.

The surviving rebels made a stand on the slopes of Mount Enodake, and were soon surrounded. Determined not to let the rebels escape again, Yamagata sent in a large force which outnumbered the Satsuma army 7:1. Most of Saigō’s remaining forces either surrendered or committed seppuku. However, Saigō burned his private papers and army uniform on August 19, and slipped away towards Kagoshima with his remaining able-bodied men. Despite Yamagata's efforts over the next several days, Saigō and his remaining 500 men reached Kagoshima on September 1 and seized Shiroyama, overlooking the city.

Kagoshima boto shutsujinzu by Yoshitoshi

Kumamoto Castle

Saigō Takamori Gunmusho (軍務所) banknote, issued in 1877 to finance his war effort. Japan Currency Museum.

Battle of Tabaruzaka: Imperial troops on the left, rebel samurai troops on the right

Battle of Tabaruzaka

Saigo's army clashes with the government's forces

Battle of Shiroyama

Battle of Shiroyama.

Saigō and his remaining samurai were pushed back to Kagoshima where, in a final battle, the Battle of Shiroyama, Imperial Army troops under the command of General Yamagata Aritomo and marines under the command of Admiral Kawamura Sumiyoshi outnumbered Saigō 60-to-1. However, Yamagata was determined to leave nothing to chance. The imperial troops spent several days constructing an elaborate system of ditches, walls and obstacles to prevent another breakout. The five government warships in Kagoshima harbor added their firepower to Yamagata's artillery, and began to systematically reduce the rebel positions.

Imperial Japanese Army fortifications encircling Shiroyama. 1877 photograph.

After Saigō rejected a letter dated September 1 from Yamagata drafted by a young Suematsu Kenchō (see M. Matsumura, Pōtsumasu he no michi, pub. Hara Shobo, 1987, Chapter 1) asking him to surrender, Yamagata ordered a full frontal assault on September 24, 1877. By 6 a.m., only 40 rebels were still alive. Saigō was severely wounded. Legend says that one of his followers, Beppu Shinsuke acted as kaishakunin and aided Saigō in committing seppuku before he could be captured. However, other evidence contradicts this, stating that Saigō in fact died of the bullet wound and then had his head removed by Beppu in order to preserve his dignity.

After Saigo's death, Beppu and the last of the "ex-samurai" drew their swords and plunged downhill toward the Imperial positions and to their deaths. With these deaths, the Satsuma rebellion came to an end.

Aftermath

Soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army during the Satsuma Rebellion.

Financially, crushing the Satsuma Rebellion cost the government greatly, forcing Japan off the gold standard and causing the government to print paper currency. The rebellion also effectively ended the samurai class, as the new Imperial Japanese Army built of conscripts without regard to social class had proven itself in battle. Saigō Takamori was labeled as a tragic hero by the people and on February 22, 1889, Emperor Meiji pardoned Saigō posthumously.

Order of battle

Organization of the Imperial Forces

At the start of the Satsuma Rebellion, the Imperial Japanese Army (including the Imperial Guard) numbered approximately 34,000 men. The line infantry was divided into 14 regiments of three battalions each. Each battalion consisted of four companies. In peacetime, each company had approximately 160 privates and 32 officers and non-commissioned officers. During war a company's strength was to be increased to 240 privates. A battalion had 640 men in peacetime and theoretically 960 men in wartime. They were armed with breech-loading Snider rifles and could fire approximately six rounds per minute.

There were two "regiments" of line cavalry and one "regiment" of imperial guard cavalry. Contemporary illustrations show the cavalry armed with lances.

The Imperial Artillery consisted of 18 batteries divided into 9 battalions, with 120 men per battery during peacetime. During war, the mountain artillery had a nominal strength of 160 men per battery and field artillery had 130 men per battery. Artillery consisted of over 100 pieces, including 5.28 pound mountain guns, Krupp field guns of various calibers, and mortars.

The Imperial Guard (mostly ex-samurai) was always maintained at wartime strength. The Guard infantry was divided into 2 regiments of 2 battalions each. A battalion was 672 men strong and was organized as per the line battalions. The cavalry regiment consisted of 150 men. The artillery battalion was divided into 2 batteries with 130 men per battery.

Japan was divided into six military districts: Tokyo, Sendai, Nagoya, Osaka, Hiroshima and Kumamoto, with two or three regiments of infantry, plus artillery and other auxiliary troops, assigned to each district.

"Hunting a rat": satirical drawing of the Satsuma rebellion, in the 1877 English language Japan Punch. The rat's tail reads "新政厚徳" ("New government, high morality", the slogan of the rebel movement), and the rat is surrounded by baton-wielding policemen.

In addition to the army, the central government also used marines and Tokyo policemen in its struggle against Satsuma. The police, in units ranging from 300 to 600 men, were mostly ex-samurai (ironically, many of whom were from Satsuma) and were armed only with wooden batons and swords (Japanese police did not carry firearms until the Rice Riots of 1918).

During the conflict, the government side expended on average 322,000 rounds of ammunition and 1,000 artillery shells per day.[4]

Organization of the Satsuma forces

The Satsuma samurai were initially organized into six battalions of 2,000 men each. Each battalion was divided into ten companies of 200 men. On its march to Kumamoto castle, the army was divided into three divisions; a vanguard of 4,000 men, the main division of 4,000 men, and a rearguard of 2,000 men. In addition, there were 200 artillerymen and 1,200 laborers. In April 1877, Saigō reorganized the army into nine infantry units of 350 to 800 men each.

The samurai were armed with swords and Model 1857 Six Line (Russian) muzzle loading rifles that could fire approximately one round per minute. Their artillery consisted of 28 mountain guns, two field guns, and 30 assorted mortars.

Name

In English the most common name for the war is the "Satsuma Rebellion". Mark Ravina, the author of The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori, argued that "Satsuma Rebellion" is not the best name for the war because the English name does not well represent the war and its Japanese name. Ravina said that the war's scope was much farther than Satsuma, and he characterizes the event as being closer to a civil war than a rebellion. Ravina prefers the English name "War of the Southwest."[5]

See also

Japan portal

Japan portal

Military history portal

Military history portal

Notes

^ ab Hane Mikiso Modern Japan A Historical survey p. 115

^ https://www.thoughtco.com/the-satsuma-rebellion-195570

^ Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan from Tokugawa Times to the Present, Second Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 84.

^ Perrin, p.76

^ Ravina, Mark. The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori. John Wiley and Sons, 2011. Names, Romanizations, and Spelling (page 2 of 2). Retrieved from Google Books on August 7, 2011. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 1-118-04556-4,

ISBN 978-1-118-04556-5.

Bibliography

Augustus Henry Mounsey (1879). The Satsuma Rebellion, an Episode of Modern Japanese History. J. Murray.

Beasley, William G. (1972). The Meiji Restoration. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0815-0.

Craig, T. (1999). Remembering Aizu: The Testament of Shiba Goro. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2157-2.

Drea, Edward J. (2009). Japan's Imperial Army: Its Rise and Fall, 1853–1945. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-8032-1708-0.

Gordon, Andrew (2003). A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511061-7.

Henshall, K. (2001). A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-23370-1.

Jansen, Marius B. (2002). The Making of Modern Japan. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-6740-0334-9.

Keane, Donald (2005). Emperor Of Japan: Meiji And His World, 1852–1912. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12341-8.

Perrin, Noel (1979). Giving up the gun. Boston: David R. Godine. ISBN 0-87923-773-2.

Ravina, Mark (2004). The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-08970-2.

Sims, Richard (2001). Japanese Political History Since the Meiji Renovation, 1868-2000. Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-23914-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Satsuma Rebellion. |

- Satsuma Rebellion: Satsuma Clan Samurai Against the Imperial Japanese Army

- Organization of Imperial and Satsuma Forces