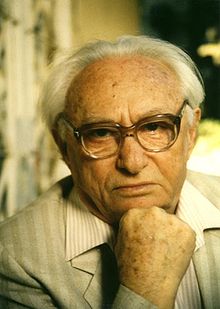

Israel Eldad

Israel Eldad | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | ישראל אלדד |

| Born | Israel Scheib November 11, 1910 Pidvolochysk, Galicia |

| Died | January 22, 1996 (aged 85) Jerusalem, Israel |

| Pen name | Sambatyon, Eldad |

| Citizenship | Israel |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

Israel Eldad (Hebrew: ישראל אלדד) (11 November 1910 – 22 January 1996), was an Israeli Revisionist Zionist philosopher and member of the pre-state underground group Lehi.

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 Career and activism

3 Views and opinions

4 Writings

5 Awards

6 Legacy and commemoration

7 Published works

8 See also

9 References

10 Further reading

Early life and education

Israel Scheib (later Eldad) was born in 1910 in Pidvolochysk, Galicia in a traditional Jewish home. The Scheibs wandered as refugees during the First World War. In 1918, in Lvov, young Scheib witnessed a funeral procession for Jews murdered in a pogrom.

After high school, Scheib enrolled at the Rabbinical Seminary of Vienna for religious studies and the University of Vienna for secular studies. He completed his doctorate on "The Voluntarism of Eduard von Hartmann, Based on Schopenhauer," but never took his rabbinical exams at the seminary.[1]

Meanwhile, he attended, with his father, a protest demonstration in front of the local British Consulate following the 1929 Arab riots in Palestine. The next year he read a poem by Uri Zvi Greenberg, "I'll Tell It to a Child," about a messiah who cannot redeem his people because they are not ready to accept redemption. Two or three years later, Scheib met Greenberg at a speech Greenberg was giving entitled “The Land of Israel Is in Flames.”

Career and activism

Scheib's first job after graduation was high school teaching in Volkovisk. He also published articles in Revisionist Zionist journals and became the commander of a local Betar section.

Scheib joined the staff of the Teachers Seminary in Vilna in 1937 while this city was part of Poland, where he stayed for two years. During that time he rose in the Betar ranks to the position of regional staff officer. In 1938, at the Third Betar Conference in Warsaw, when the Revisionist leader Zeev Jabotinsky attacked the militant stance of Poland's Betar leader Menachem Begin, Scheib spoke in Begin's defense.[2] The next year, when the Second World War broke out, Scheib and Begin escaped together from Warsaw. Begin was arrested by the Soviet police in the middle of a chess game with Scheib, and it was several years before they met again in British Mandatory Palestine, where Scheib was already a leader of the Lehi underground and Begin would soon command the Irgun. The Lehi was at that point waging a violent struggle for freedom from British rule and the Irgun would, under Begin, soon join the revolt in hopes of turning Palestine into a Jewish state.

Plaque commemorating the escape of Eldad, in Jerusalem.

Scheib adopted several aliases while living underground, including "Sambatyon" and "Eldad". He worked in 1942 directly with Lehi founder Avraham Stern. After Stern's killing by the British, Eldad became one of a triumvirate of Lehi commanders, serving with Natan Yellin-Mor and future prime minister Yitzhak Shamir. It was in this role that, in September 1948, Eldad participated in ordering the assassination of Folke Bernadotte, a United Nations mediator, as he subsequently admitted.[3][4] Yellin-Mor was the diplomatic "foreign minister," Shamir the operations man, and Eldad the ideologue. For the next six years Eldad wrote articles for various underground newspapers, some of which he edited. Eldad also wrote some of the speeches delivered in court by Lehi defendants.[3]

Eldad was arrested by the British fleeing from a Tel Aviv apartment; he was injured in a fall from a water pipe, and imprisoned in the Jerusalem prison in a body cast. He continued his political and philosophical writing from Cell 18 of the hospital ward at the Jerusalem Central Prison. Eventually Eldad healed enough to escape while on a visit in a dentist's clinic, from which several Lehi fighters spirited him away.

Israel Eldad. Circa 1948.

During Israel's War of Independence, Eldad was critical of Menachem Begin's Irgun for what he thought of not fighting against the Israel Defence Forces during the Altalena Affair . He was also critical of the IDF for not fighting harder to conquer Jerusalem's Old City and critical of Lehi fighters who did not rush to fight in Jerusalem. Towards the end of the war, Eldad disguised himself as a foreign journalist in order to sneak past Israeli military roadblocks and join the battle for Jerusalem.

The Lehi veterans organized politically as the Fighters' List. The party won one seat in the election for the First Knesset and dissolved afterwards. At one party meeting, Eldad lectured on Sulam, Jacob's ladder (based on Genesis 28:10-19, where Jacob dreams of a ladder uniting heaven and earth), thus beginning the next chapter in his life. For 14 years he published a revolutionary journal, Sulam. Eldad also spent half of 1949 writing his memoirs, entitled Maaser Rishon.

Eldad eventually got a job teaching Bible and Hebrew literature in an Israeli high school, until Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion intervened and had him dismissed. Ben-Gurion was afraid Eldad would imbue the students with his Lehi ideology. Eldad went to court and won, but found few people willing to hire him after Ben-Gurion had labeled him a danger to the state. Eldad turned to literary work, wrote histories of underground battles, a biography of the mayor of Ramat Gan, a newspaper-style review of Jewish history called Chronicles, a book of Bible commentary, Hegionot Mikra, weekly newspaper columns, and many more books, encyclopedia entries and other works. In 1962, Eldad was made a lecturer at the Technion in Haifa. He taught there for twenty years. Since 1982 was a lecturer at the Ariel University Center of Samaria. In 1988, Eldad was awarded Tel Aviv's Bialik Prize for his contributions to Israeli thought.

By the 1990s, Eldad was known as the doyen of Israeli nationalists. He died on the first day of the Hebrew month of Shevat, in January 1996. His funeral was attended by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, former prime minister Yitzhak Shamir and Knesset Speaker Dov Shilansky. Eldad was buried on the Mount of Olives,[5] at the foot of the grave of his mentor and friend, Uri Zvi Greenberg.

Views and opinions

Eldad did not believe that the creation of the state of Israel was the goal of Zionism. He considered the state a tool to be used in realizing the goal of Zionism, which he called Malkhut Yisrael (the Kingdom of Israel). Eldad sought what he referred to as national redemption, meaning a sovereign Jewish kingdom in the biblical borders of Israel, with all the world's Jews living there, and the Jewish Temple rebuilt in Jerusalem.[6] Eldad steadfastly refused to give legitimacy to any Jewish presence in the Diaspora, which he felt was doomed to extinction. Nonetheless, in his view of history, past generations of Jews in exile from the Land of Israel were not denigrated as passive sufferers, but were considered creative players in history.[7] Eldad and his journal Sulam wrote frequently about Jewish political figures who throughout history tried to bring redemption to their people, but who were stymied by geopolitical or other obstacles.[citation needed]

Eldad called on all Jews to join in the building of Israel, not for their personal fulfillment but because they are needed there.[citation needed]

Politically, Eldad favored an independent foreign policy, with Israel not a member of any foreign bloc. He advocated more forceful use of the Israel Defense Forces and opposed the inclusion of the word "defense" in the name of the army. He opposed ceding any land to the Arabs.[citation needed]

Writings

Much of Eldad's voluminous writings has been translated into English, mostly by Zev Golan.[8] Among his works: Chronicles .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}ISBN 965-7108-15-2. The Jewish Revolution appeared in 1971, and was reissued in 2007. Free Jerusalem includes a chapter by Eldad ("Meanwhile, A European Interlude") about Polish Jewry on the eve of war. Israel: The Road to Full Redemption, a translation of an article in Sulam, was published in 1961 and is today a virtually unobtainable brochure. A website is devoted to disseminating articles by Eldad and his underground colleagues.[9] His memoirs of the time he led the Lehi underground organisation, The First Tithe, were translated and first published in 2008. God, Man and Nietzsche includes a lengthy examination of Eldad's philosophy of history and excerpts from an article about Nietzsche written by Eldad in the underground.[10]Stern: The Man and His Gang has a biography of Eldad and a detailed comparison of his political ideas and goals with those of other Lehi leaders.

Awards

- In 1977, Eldad was awarded the Tchernichovsky Prize for exemplary translation.

- In 1988, he was the co-recipient (jointly with Zvi Meir Rabinovitz) of the Bialik Prize for Jewish thought.[11]

- In 1990, he received the Yakir Yerushalayim (Worthy Citizen of Jerusalem) award from the city of Jerusalem.[12]

Legacy and commemoration

Many of Eldad's political and philosophical teachings continue to be espoused by the Magshimey Herut (achievers of liberty) organization, the Zionist Freedom Alliance, and by the Hatikva political party, the latter one led by Eldad's son Aryeh. The Israeli settlement Kfar Eldad was named after him.

Published works

The Jewish Revolution: Jewish Statehood (Israel: Gefen Publishing House, 2007),

ISBN 978-965-229-414-2

Maaser Rishon. Originally published in 1950 in Hebrew. English translation: The First Tithe (Tel Aviv: Jabotinsky Institute, 2008),

ISBN 978-965-416-015-5

Israel: The Road to Full Redemption (New York: Futuro Press, 1961)

See also

- List of Bialik Prize recipients

References

^ Ada Amichal Yevin, Sambatyon, pp. 26-30 (Hebrew)

^ Israel Eldad, Maaser Rishon, pp. 21-25 (Hebrew)

^ ab Moshe and Tova Svorai, Me'Etzel Le'Lechi, 1989, pp. 419-422 (Hebrew) and Israel Eldad, Maaser Rishon, pp. 133-145 (Hebrew)

^ C. D. Stanger (1988). "A haunting legacy: The assassination of Count Bernadotte". Middle East Journal. 42 (2): 260–272.

^ Jerusalem Post, January 23, 1996

^ Israel Eldad, Israel: The Road to Full Redemption, p. 37 (Hebrew) and Israel Eldad, "Temple Mount in Ruins"

^ Zev Golan, God, Man and Nietzsche, p. 113

^ "Zev Golan". Gefen Books.

^ "Save Israel".

^ "New Book Reveals Underground Secrets". Jabotinsky Institute in Israel. Archived from the original on 2010-07-07.

^ "List of Bialik Prize recipients 1933-2004 (in Hebrew), Tel Aviv Municipality website" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-17.

^ "Recipients of Yakir Yerushalayim award (in Hebrew)". Archived from the original on 2011-06-17. City of Jerusalem official website

Further reading

- Ada Amichal Yevin, Sambatyon (Israel: Bet El, 1995) (Hebrew)

- Zev Golan, Free Jerusalem: Heroes, Heroines and Rogues Who Created the State of Israel (Israel: Devora, 2003),

ISBN 1-930143-54-0

- Zev Golan, God, Man and Nietzsche: A Startling Dialogue between Judaism and Modern Philosophers (New York: iUniverse, 2007),

ISBN 0-595-42700-6