Locality (linguistics)

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

Subfields

|

Grammatical Theories

|

Topics

|

Linguistics portal |

In linguistics, locality refers to the proximity of elements in a linguistic structure. Constraints on locality limit the span over which rules can apply to a particular structure. Theories of transformational grammar use syntactic locality constraints to explain restrictions on argument selection, syntactic binding, and syntactic movement.

Contents

1 Where locality is observed

1.1 Selection

1.2 Binding

1.3 Movement

1.3.1 Seven sentences

1.3.1.1 Wh-island constraint

1.3.1.2 Adjunct island condition

1.3.1.3 Sentential subject constraint

1.3.1.4 Coordinate structure constraint

1.3.1.5 Complex NP constraint

1.3.1.6 Subject condition

1.3.1.7 Left branch constraint

2 See also

3 References

Where locality is observed

Locality is observed in a number of linguistic contexts, and most notably with:

- Selection of arguments; this is regulated by the projection principle

- Binding of two DPs; this is regulated by binding theory

- Displacement of wh-phrases; this is regulated by wh-movement

Selection

The projection principle requires that lexical properties — in particular argument structure properties such as thematic roles — be "projected" onto syntactic structures. Together with Locality of Selection, which forces lexical properties to be projected within a local projection (as defined by X-bar theory[1]:149), the projection principle constrains syntactic trees.

| Locality of Selection |

|---|

| Every argument that α selects must appear in the local domain of α. |

.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery{display:table}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery-default{background:transparent;margin-top:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery-center{margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery-left{float:left}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery-right{float:right}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery-none{float:none}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery-collapsible{width:100%}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery .title{display:table-row}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery .title>div{display:table-cell;text-align:center;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery .main{display:table-row}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery .main>div{display:table-cell}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery .caption{display:table-row;vertical-align:top}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery .caption>div{display:table-cell;display:block;font-size:94%;padding:0}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery .footer{display:table-row}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery .footer>div{display:table-cell;text-align:right;font-size:80%;line-height:1em}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery .gallerybox .thumb img{background:none}.mw-parser-output .mod-gallery .bordered-images img{border:solid #eee 1px}

Local projections of the head

According to locality of selection, the material introduced in the syntactic tree must have a local relationship with the head that introduces it. This means that each argument must be introduced into the same projection as its head. Therefore, each complement and specifier will appear within the local projection of the head that selects it.

For example, the contrast between the well-formed (1a) and the ill-formed (1b) shows that in English, an adverb cannot intervene between a head (the verb study) and its complement (the DP the report).

(1) a. John carefully [Vstudies] [DPthe report]. |

In structural accounts of the contrast between (1a) and (1b), the two sentences differ relative to their underlying structure. The starting point is the lexical entry for the verb study, which specifies that the verb introduces two arguments, namely a DP which bears the semantic role of Agent, and another DP which bears the semantic role of Theme.

lexical entry for study: V, <DPAGENT,DPTHEME>

In the tree for sentence (1a), the verb is the Head of the VP projection, the DPTHEME is projected onto the Complement position (as sister to the head V), and the DPAGENT is projected onto the Specifier (as sister to V'). In this way, (1a) satisfies Locality of Selection as both arguments are projected within the projection of the head that introduces them. In addition, the AdvP carefully attaches as an unselected adjunct to VP; structurally this means that it is outside of the local projection of V as it is sister to and dominated by VP. In contrast, in the tree for sentence (1b), the introduction of the AdvP carefully as sister to the verb study violates Locality of Selection; this is because the lexical entry of the verb study does not select an AdvP, so the latter cannot be introduced in the local projection of the verb.

John carefully studies the report.

- John studies carefully the report.

Binding

Locality in binding theory refers to Principle A, where binding of an anaphor and its antecedent must occur within the local domain. Therefore, the antecedent should be in the same clause that contains the anaphor. A clause is the domain if and only if it is the smallest XP containing a DP that c-commands the anaphor and has a subject.[1]

The following examples show the application of Principle A in binding theory:

(2) a. Mary revealed [DP John]i to [DP himself]i. |

Mary revealed John to himself.

- Mary revealed himself to John.

Example (2a) is predicted to be grammatical by Principle A of binding theory. The anaphor and antecedent appear within the same TP domain: TP is the smallest XP that contains the anaphor and DP subject (in this case, the subject is the antecedent). However, in example (2b), the anaphor and antecedent are not bound within the same domain, therefore, the sentence is predicted to be ungrammatical.

(3) a. John heard [DP their]i criticisms of [DP each other]i. |

John heard their critisms of each other.

- They heard John's criticisms of each other.

Example (3) is similar to example (2). (3a) is grammatical because the anaphor is bound within the same domain as the antecedent. However, example (3b) is ungrammatical since the anaphor and antecedent appear within different domains. The anaphor is not bound.

Movement

Movement is the phenomenon that accounts for the possibility of a single syntactic constituent or element occupying multiple, yet distinct locations, depending on the type of sentence it is in.[2]

In wh-movement, an interrogative sentence is formed by moving the wh-word (determiner phrase, preposition phrase, or adverb phrase) to the specifier position of the complementizer phrase. The +q feature of the complementizer results in an EPP:XP+q feature: This forces an XP to the specifier position of CP. The +q feature also attracts the bound morpheme in the tense position to move to the head complementizer position; leading to do-support.[1]:260–262

Seven sentences

There are seven types violations that can occur for wh-movement. These constraints predict the environments in which movement generates an ungrammatical sentence: Movement does not occur locally.

Wh-island constraint

| The Wh-island Constraint |

|---|

| If CP has the feature +q, movement of a wh-phrase to a position outside of the clause cannot occur.[1]:271 |

This definition tells us that if the specifier position of CP is occupied or if a C is occupied by a +q word, movement of a wh-phrase out of the CP cannot occur.[1]:271

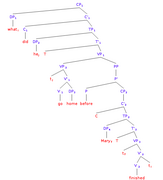

(4) a. [DP Who]i do you wonder [DP e]i bought what? |

Who do you wonder bought what?

- What do you wonder who bought?

Example (4b) illustrates the wh-island constraint. The embedded clause contains a complementizer with the feature +q. This causes the DP "who" to move to the specifier position of that complementizer phrase. Movement of the complement DP "what" cannot occur since the specifier position of CP is filled. Therefore, movement of the wh-word,what, generates an ungrammatical sentence, while movement of the wh-word "who" is allowed (specifier position of the embedded CP is not occupied).

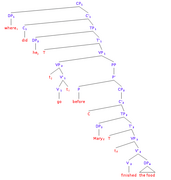

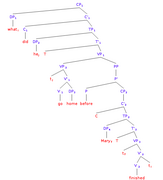

Adjunct island condition

| Adjunct Island Condition |

|---|

| If an adjunct contains a CP, movement of an element inside the CP to a position outside of the adjunct is not allowed.[1]:273 |

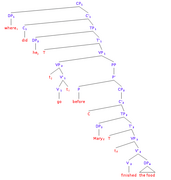

(5) a. [PP Where]i did he go [PP e]i before they finished the food? |

Where did he go before they finished the food?

- What did he go home before Mary finished?

Example (5b) demonstrates the adjunct island condition. We can see that the wh-word, "what", occurs within the complementizer phrase that appears in the adjunct. Therefore, movement of this DP out of the adjunct will generate an ungrammatical sentence. Example (5a) is grammatical because the trace of the PP "where" is not within the adjunct,therefore, movement is allowed.

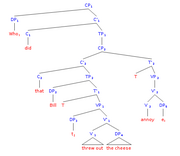

Sentential subject constraint

| The Sentential Subject Constraint |

|---|

| Movement of an element that appears within the CP subject cannot occur.[1]:273 |

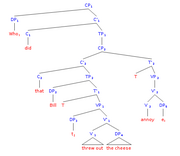

(6) a. [DP Who]i did that Bill threw out the cheese annoy [DP e]i? |

Who did that Bill threw out the cheese annoy?

- What did that Bill threw out annoy you?

Example (6b) displays the sentential subject condition. The subject of the verb in this sentence is a complementizer clause. The DP "what" that appears within the CP subject moves to the specifier position of the main clause. The sentential subject constraint predicts that this wh-movement will result in an ungrammatical sentence since the trace was within the CP subject. Example (6a) is grammatical because the DP "who" does not have a trace within the CP subject, therefore, allowing movement to occur.

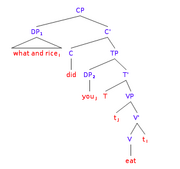

Coordinate structure constraint

| The Coordinate Structure Constraint |

|---|

| An element within a conjunct cannot undergo movement out of the conjunct.[1]:278 |

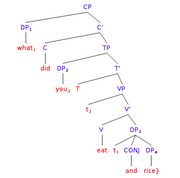

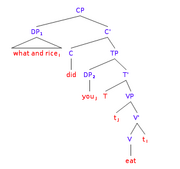

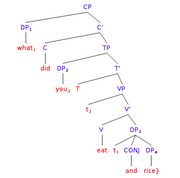

(7) a. [DP What and [rice]i did you eat [DP e]i? |

What and rice did you eat?

- What did you eat and rice?

Example (7a) is grammatical since the DP complement is moving as a whole to the specifier position of the matrix clause; nothing is extracted from the larger DP. Example (7b) is an example of the coordinate structure constraint. The DP "what" originally occurs within the DP conjunct, therefore, this constraint predicts that an ungrammatical sentence will result due to the extraction of an element within the conjunct.[1]:278

Complex NP constraint

| The Complex Noun Phrase Constraint |

|---|

| Extraction of an element that is a complement or adjunct of a NP is not allowed.[1]:274 |

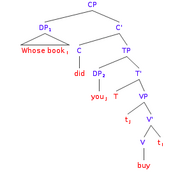

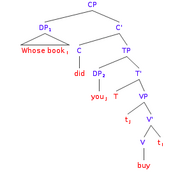

(8) a. [DP Whose book]i did you buy [DP e]i? |

Whose book did you buy?

- Whose did you buy book?

Example (8a) is grammatical because the DP complement of the verb moves as a whole to the specifier position of the main clause. Example (8b) displays the complex noun phrase constraint. The NP complement D "whose" is extracted and moved to the specifier position of the main clause. The complex noun phrase constraint predicts that this wh-movement will result in an ungrammatical sentence since extraction of an element within the complex NP is not allowed.

Subject condition

| The Subject Condition |

|---|

| Movement of a DP out of the subject DP of the verb is not allowed.[1]:277 |

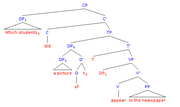

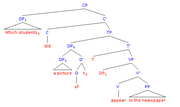

(9) a. A picture of which students appeared in the newspapers? |

A picture of which students appeared in the newspapers?

- Which students did a picture of appear in the newspapers?

Example (9a) does not display any wh-movement. Therefore, the sentence is grammatical since nothing is extracted from the subject DP. Example (9b) contains wh-movement of a DP that is within the subject DP. The subject condition tells us that this type of movement is not allowed and the sentence will be ungrammatical.[1]:277

Left branch constraint

| The Left Branch Constraint |

|---|

| Extraction of a DP subject within a larger DP cannot occur.[1]:278 |

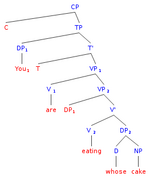

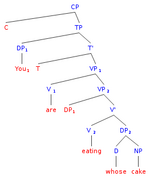

(10) a. You are eating [DP [DP whose] cake]. |

You are eating whose cake.

- Whose are you eating cake?

In example (10a), there is no wh-movement, therefore the left branch constraint does not apply and this sentence is grammatical. In example (10b), the DP "whose" is extracted from the larger DP "whose cake." This extraction under the left branch constraint is not allowed, therefore, the sentence is predicted to be ungrammatical. This sentence can be made grammatical by moving larger DP as a unit to the specifier position of CP.[1]:278

(10) c. [DP Whose cake]i are you eating [DP ei]? [1]:278 |

In example (10c), the whole subject DP structure undergoes wh-movement, which results in a grammatical sentence. This suggests that pied-piping can be used to reverse the effects of the violations or extraction constraints.[1]:278

(24) *[DP What]i did you wonder who ate ei? [1]:271 |

- What did you wonder who ate?

Example (24) is an example of a wh-island violation. There are two TP bounding nodes that appear between the DP "what" and its trace. Therefore, according to the subjacency condition, movement will result in an ungrammatical sentence.[1]:271

See also

- Projection Principle

- Wh-movement

- Selection

- Binding Theory

- Subjacency

- X-bar Theory

- PRO

- Control Theory

References

^ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwx Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0017-5..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Haegeman, Liliane; Guéron, Jacqueline (1999). English Grammar: A Generative Perspective. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers Inc. ISBN 0-631-18839-8.