Trade

A trader in Germany, 16th century

The San Juan de Dios Market in Guadalajara, Jalisco.

The Liberty to Trade as Buttressed by National Law (1909) by George Howard Earle, Jr.

| Business administration |

|---|

Management of a business |

Accounting

|

Business entities

|

Corporate governance

|

Corporate law

|

Economics

|

Finance

|

Marketing

|

Types of management

|

Organization

|

Trade

|

|

Trade involves the transfer of goods or services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. A system or network that allows trade is called a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exchange of goods and services for other goods and services.[1][need quotation to verify] Barter involves trading things without the use of money.[1] Later, one bartering party started to involve precious metals, which gained symbolic as well as practical importance.[citation needed] Modern traders generally negotiate through a medium of exchange, such as money. As a result, buying can be separated from selling, or earning. The invention of money (and later credit, paper money and non-physical money) greatly simplified and promoted trade. Trade between two traders is called bilateral trade, while trade involving more than two traders is called multilateral trade.

Trade exists due to specialization and the division of labor, a predominant form of economic activity in which individuals and groups concentrate on a small aspect of production, but use their output in trades for other products and needs.[2] Trade exists between regions because different regions may have a comparative advantage (perceived or real) in the production of some trade-able commodity—including production of natural resources scarce or limited elsewhere, or because different regions' sizes may encourage mass production.[3] In such circumstances, trade at market prices between locations can benefit both locations.

Retail trade consists of the sale of goods or merchandise from a very fixed location[4] (such as a department store, boutique or kiosk), online or by mail, in small or individual lots for direct consumption or use by the purchaser.[5]Wholesale trade is defined[by whom?] as traffic in goods that are sold as merchandise to retailers, or to industrial, commercial, institutional, or other professional business users, or to other wholesalers and related subordinated services.

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Prehistory

2.2 Ancient history

2.3 Later trade

2.3.1 Mediterranean and Near East

2.3.2 The Orient

2.3.3 Mesoamerica

2.4 Middle Ages

2.5 The Age of Sail and the Industrial Revolution

2.6 19th century

2.7 20th century

2.8 21st century

2.9 Free trade

3 Perspectives

3.1 Protectionism

3.2 Religion

3.3 Development of money

4 Trends

4.1 Doha rounds

4.2 China

5 International trade

5.1 Trade sanctions

5.2 Trade barriers

5.3 Fair trade

6 See also

7 Notes

8 Bibliography

9 External links

Etymology

Commerce is derived from the Latin commercium, from cum "together" and merx, "merchandise."[6]

Trade from Middle English trade ("path, course of conduct"), introduced into English by Hanseatic merchants, from Middle Low German trade ("track, course"), from Old Saxon trada ("spoor, track"), from Proto-Germanic *tradō ("track, way"), and cognate with Old English tredan ("to tread").

History

Prehistory

Trade originated with human communication in prehistoric times. Trading was the main facility of prehistoric people, who bartered goods and services from each other before the innovation of modern-day currency. Peter Watson dates the history of long-distance commerce from circa 150,000 years ago.[7]

In the Mediterranean region the earliest contact between cultures were of members of the species Homo sapiens principally using the Danube river, at a time beginning 35,000–30,000 BCE.[8][9][10]

Some trace the origins of commerce to the very start of transaction in prehistoric times. Apart from traditional self-sufficiency, trading became a principal facility of prehistoric people, who bartered what they had for goods and services from each other.

The caduceus has been used today as the symbol of commerce[11] with which Mercury has traditionally been associated.

Ancient history

Ancient Etruscan "aryballoi" terracota vessels unearthed in the 1860s at Bolzhaya Bliznitsa tumulus near Phanagoria, South Russia (then part of the Bosporan Kingdom of Cimmerian Bosporus); on exhibit at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

Trade is believed to have taken place throughout much of recorded human history. There is evidence of the exchange of obsidian and flint during the stone age. Trade in obsidian is believed to have taken place in Guinea from 17,000 BCE.[12][13]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The earliest use of obsidian in the Near East dates to the Lower and Middle paleolithic.[14]

— HIH Prince Mikasa no Miya Takahito

Trade in the stone age was investigated by Robert Carr Bosanquet in excavations of 1901.[15][16] Trade is believed to have first begun in south west Asia.[17][18]

Archaeological evidence of obsidian use provides data on how this material was increasingly the preferred choice rather than chert from the late Mesolithic to Neolithic, requiring exchange as deposits of obsidian are rare in the Mediterranean region.[19][20][21]

Obsidian is thought to have provided the material to make cutting utensils or tools, although since other more easily obtainable materials were available, use was found exclusive to the higher status of the tribe using "the rich man's flint".[17]

Obsidian was traded at distances of 900 kilometres within the Mediterranean region.[22]

Trade in the Mediterranean during the Neolithic of Europe was greatest in this material.[19][23] Networks were in existence at around 12,000 BCE[24] Anatolia was the source primarily for trade with the Levant, Iran and Egypt according to Zarins study of 1990.[25][26][27]Melos and Lipari sources produced among the most widespread trading in the Mediterranean region as known to archaeology.[28]

The Sari-i-Sang mine in the mountains of Afghanistan was the largest source for trade of lapis lazuli.[29][30] The material was most largely traded during the Kassite period of Babylonia beginning 1595 BCE.[31][32]

Later trade

Mediterranean and Near East

Ebla was a prominent trading centre during the third millennia, with a network reaching into Anatolia and north Mesopotamia.[28][33][34][35]

A map of the Silk Road trade route between Europe and Asia.

Materials used for creating jewelry were traded with Egypt since 3000 BCE. Long-range trade routes first appeared in the 3rd millennium BCE, when Sumerians in Mesopotamia traded with the Harappan civilization of the Indus Valley. The Phoenicians were noted sea traders, traveling across the Mediterranean Sea, and as far north as Britain for sources of tin to manufacture bronze. For this purpose they established trade colonies the Greeks called emporia.[citation needed][36]

From the beginning of Greek civilization until the fall of the Roman empire in the 5th century, a financially lucrative trade brought valuable spice to Europe from the far east, including India and China. Roman commerce allowed its empire to flourish and endure. The latter Roman Republic and the Pax Romana of the Roman empire produced a stable and secure transportation network that enabled the shipment of trade goods without fear of significant piracy, as Rome had become the sole effective sea power in the Mediterranean with the conquest of Egypt and the near east.[37]

In ancient Greece Hermes was the god of trade[38][39] (commerce) and weights and measures,[40] for Romans Mercurius also god of merchants, whose festival was celebrated by traders on the 25th day of the fifth month.[41][42] The concept of free trade was an antithesis to the will and economic direction of the sovereigns of the ancient Greek states. Free trade between states was stifled by the need for strict internal controls (via taxation) to maintain security within the treasury of the sovereign, which nevertheless enabled the maintenance of a modicum of civility within the structures of functional community life.[43][44]

The fall of the Roman empire, and the succeeding Dark Ages brought instability to Western Europe and a near collapse of the trade network in the western world. Trade however continued to flourish among the kingdoms of Africa, Middle East, India, China and Southeast Asia. Some trade did occur in the west. For instance, Radhanites were a medieval guild or group (the precise meaning of the word is lost to history) of Jewish merchants who traded between the Christians in Europe and the Muslims of the Near East.[45]

The Orient

Archaeological evidence (Greenberg 1951) of the first use of trade-marks are from China dated about 2700 BCE.[46]

Mesoamerica

Tajadero or axe money used as currency in Mesoamerica. It had a fixed worth of 8,000 cacao seeds, which were also used as currency.[47]

The emergence of exchange networks in the Pre-Columbian societies of and near to Mexico are known to have occurred within recent years before and after 1500 BCE.[48]

Trade networks reached north to Oasisamerica. There is evidence of established maritime trade with the cultures of northwestern South America and the Caribbean.

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, commerce developed in Europe by trading luxury goods at trade fairs. Wealth became converted into movable wealth or capital. Banking systems developed where money on account was transferred across national boundaries. Hand to hand markets became a feature of town life, and were regulated by town authorities.

Western Europe established a complex and expansive trade network with cargo ships being the main workhorse for the movement of goods, Cogs and Hulks are two examples of such cargo ships.[49] Many ports would develop their own extensive trade networks. The English port city of Bristol traded with peoples from what is modern day Iceland, all along the western coast of France, and down to what is now Spain.[50]

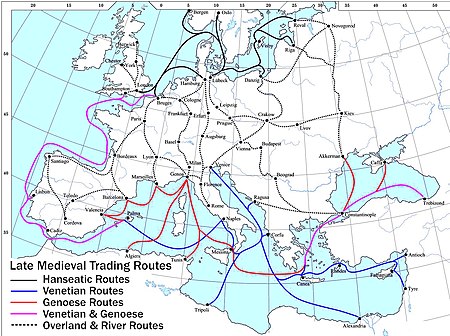

A map showing the main trade routes for goods within late medieval Europe.

During the Middle Ages, Central Asia was the economic center of the world.[51] The Sogdians dominated the East-West trade route known as the Silk Road after the 4th century CE up to the 8th century CE, with Suyab and Talas ranking among their main centers in the north. They were the main caravan merchants of Central Asia.

From the 8th to the 11th century, the Vikings and Varangians traded as they sailed from and to Scandinavia. Vikings sailed to Western Europe, while Varangians to Russia. The Hanseatic League was an alliance of trading cities that maintained a trade monopoly over most of Northern Europe and the Baltic, between the 13th and 17th centuries.

The Age of Sail and the Industrial Revolution

Vasco da Gama pioneered the European Spice trade in 1498 when he reached Calicut after sailing around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of the African continent. Prior to this, the flow of spice into Europe from India was controlled by Islamic powers, especially Egypt. The spice trade was of major economic importance and helped spur the Age of Discovery in Europe. Spices brought to Europe from the Eastern world were some of the most valuable commodities for their weight, sometimes rivaling gold.

In the 16th century, the Seventeen Provinces were the centre of free trade, imposing no exchange controls, and advocating the free movement of goods. Trade in the East Indies was dominated by Portugal in the 16th century, the Dutch Republic in the 17th century, and the British in the 18th century. The Spanish Empire developed regular trade links across both the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans.

Danzig in the 17th century, a port of the Hanseatic League.

In 1776, Adam Smith published the paper An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. It criticised Mercantilism, and argued that economic specialisation could benefit nations just as much as firms. Since the division of labour was restricted by the size of the market, he said that countries having access to larger markets would be able to divide labour more efficiently and thereby become more productive. Smith said that he considered all rationalisations of import and export controls "dupery", which hurt the trading nation as a whole for the benefit of specific industries.

In 1799, the Dutch East India Company, formerly the world's largest company, became bankrupt, partly due to the rise of competitive free trade.

Berber trade with Timbuktu, 1853.

19th century

In 1817, David Ricardo, James Mill and Robert Torrens showed that free trade would benefit the industrially weak as well as the strong, in the famous theory of comparative advantage. In Principles of Political Economy and Taxation Ricardo advanced the doctrine still considered the most counterintuitive in economics:

- When an inefficient producer sends the merchandise it produces best to a country able to produce it more efficiently, both countries benefit.

The ascendancy of free trade was primarily based on national advantage in the mid 19th century. That is, the calculation made was whether it was in any particular country's self-interest to open its borders to imports.

John Stuart Mill proved that a country with monopoly pricing power on the international market could manipulate the terms of trade through maintaining tariffs, and that the response to this might be reciprocity in trade policy. Ricardo and others had suggested this earlier. This was taken as evidence against the universal doctrine of free trade, as it was believed that more of the economic surplus of trade would accrue to a country following reciprocal, rather than completely free, trade policies. This was followed within a few years by the infant industry scenario developed by Mill promoting the theory that government had the duty to protect young industries, although only for a time necessary for them to develop full capacity. This became the policy in many countries attempting to industrialise and out-compete English exporters. Milton Friedman later continued this vein of thought, showing that in a few circumstances tariffs might be beneficial to the host country; but never for the world at large.[52]

20th century

The Great Depression was a major economic recession that ran from 1929 to the late 1930s. During this period, there was a great drop in trade and other economic indicators.

The lack of free trade was considered by many as a principal cause of the depression causing stagnation and inflation.[53] Only during the World War II the recession ended in the United States. Also during the war, in 1944, 44 countries signed the Bretton Woods Agreement, intended to prevent national trade barriers, to avoid depressions. It set up rules and institutions to regulate the international political economy: the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (later divided into the World Bank and Bank for International Settlements). These organisations became operational in 1946 after enough countries ratified the agreement. In 1947, 23 countries agreed to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade to promote free trade.[54]

The European Union became the world's largest exporter of manufactured goods and services, the biggest export market for around 80 countries.[55]

21st century

Today, trade is merely a subset within a complex system of companies which try to maximize their profits by offering products and services to the market (which consists both of individuals and other companies) at the lowest production cost. A system of international trade has helped to develop the world economy but, in combination with bilateral or multilateral agreements to lower tariffs or to achieve free trade, has sometimes harmed third-world markets for local products.

Free trade

Free trade advanced further in the late 20th century and early 2000s:

- 1992 European Union lifted barriers to internal trade in goods and labour.

- January 1, 1994 the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) took effect.

- 1994 The GATT Marrakech Agreement specified formation of the WTO.

- January 1, 1995 World Trade Organization was created to facilitate free trade, by mandating mutual most favoured nation trading status between all signatories.

- EC was transformed into the European Union, which accomplished the Economic and Monnetary Union (EMU) in 2002, through introducing the Euro, and creating this way a real single market between 13 member states as of January 1, 2007.

2005, the Central American Free Trade Agreement was signed; It includes the United States and the Dominican Republic.

Intérêts des nations de l'Europe, dévélopés relativement au commerce (1766)

Perspectives

Protectionism

Protectionism is the policy of restraining and discouraging trade between states and contrasts with the policy of free trade. This policy often takes of form of tariffs and restrictive quotas. Protectionist policies were particularly prevalent in the 1930s, between the Great Depression and the onset of World War II.

Religion

Islamic teachings encourage trading (and condemn usury or interest).[56][57]

Judeao-Christian teachings prohibit fraud and dishonest measures, and historically also forbade the charging of interest on loans.[58][59]

Development of money

A Roman denarius.

The first instances of money were objects with intrinsic value. This is called commodity money and includes any commonly available commodity that has intrinsic value; historical examples include pigs, rare seashells, whale's teeth, and (often) cattle. In medieval Iraq, bread was used as an early form of money. In Mexico under Montezuma cocoa beans were money. [6]

Currency was introduced as a standardised money to facilitate a wider exchange of goods and services. This first stage of currency, where metals were used to represent stored value, and symbols to represent commodities, formed the basis of trade in the Fertile Crescent for over 1500 years.

Numismatists have examples of coins from the earliest large-scale societies, although these were initially unmarked lumps of precious metal.[60]

Trends

Doha rounds

The Doha round of World Trade Organization negotiations aimed to lower barriers to trade around the world, with a focus on making trade fairer for developing countries. Talks have been hung over a divide between the rich developed countries, represented by the G20, and the major developing countries. Agricultural subsidies are the most significant issue upon which agreement has been hardest to negotiate. By contrast, there was much agreement on trade facilitation and capacity building. The Doha round began in Doha, Qatar, and negotiations were continued in: Cancún, Mexico; Geneva, Switzerland; and Paris, France and Hong Kong.[citation needed]

China

Beginning around 1978, the government of the People's Republic of China (PRC) began an experiment in economic reform. In contrast to the previous Soviet-style centrally planned economy, the new measures progressively relaxed restrictions on farming, agricultural distribution and, several years later, urban enterprises and labor. The more market-oriented approach reduced inefficiencies and stimulated private investment, particularly by farmers, that led to increased productivity and output. One feature was the establishment of four (later five) Special Economic Zones located along the South-east coast.[citation needed]

The reforms proved spectacularly successful in terms of increased output, variety, quality, price and demand. In real terms, the economy doubled in size between 1978 and 1986, doubled again by 1994, and again by 2003. On a real per capita basis, doubling from the 1978 base took place in 1987, 1996 and 2006. By 2008, the economy was 16.7 times the size it was in 1978, and 12.1 times its previous per capita levels. International trade progressed even more rapidly, doubling on average every 4.5 years. Total two-way trade in January 1998 exceeded that for all of 1978; in the first quarter of 2009, trade exceeded the full-year 1998 level. In 2008, China's two-way trade totaled US$2.56 trillion.[61]

In 1991 China joined the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation group, a trade-promotion forum.<https://www.apec.org/About-Us/About-APEC/Member-Economies> In 2001, it also joined the World Trade Organization.<https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/china_e.htm>

International trade

| Part of a series on |

| World trade |

|---|

|

Policy

|

Restrictions

|

History

|

Organizations

|

Economic integration

|

Issues

|

Lists

|

By country

|

Theory

|

International trade is the exchange of goods and services across national borders. In most countries, it represents a significant part of GDP. While international trade has been present throughout much of history (see Silk Road, Amber Road), its economic, social, and political importance have increased in recent centuries, mainly because of Industrialization, advanced transportation, globalization, multinational corporations, and outsourcing.[citation needed]

Empirical evidence for the success of trade can be seen in the contrast between countries such as South Korea, which adopted a policy of export-oriented industrialization, and India, which historically had a more closed policy. South Korea has done much better by economic criteria than India over the past fifty years, though its success also has to do with effective state institutions.[citation needed]

Trade sanctions

Trade sanctions against a specific country are sometimes imposed, in order to punish that country for some action. An embargo, a severe form of externally imposed isolation, is a blockade of all trade by one country on another. For example, the United States has had an embargo against Cuba for over 40 years.[62]

Trade barriers

International trade, which is governed by the World Trade Organization, can be restricted by both tariff and non-tariff barriers. International trade is usually regulated by governmental quotas and restrictions, and often taxed by tariffs. Tariffs are usually on imports, but sometimes countries may impose export tariffs or subsidies. Non-tariff barriers include Sanitary and Phytosanitary rules, labeling requirements and food safety regulations. All of these are called trade barriers. If a government removes all trade barriers, a condition of free trade exists. A government that implements a protectionist policy establishes trade barriers. There are usually few trade restrictions within countries although a common feature of many developing countries is police and other road blocks along main highways, that primarily exist to extract bribes.[citation needed]

Fair trade

The "fair trade" movement, also known as the "trade justice" movement, promotes the use of labour, environmental and social standards for the production of commodities, particularly those exported from the Third and Second Worlds to the First World. Such ideas have also sparked a debate on whether trade itself should be codified as a human right.[63]

Importing firms voluntarily adhere to fair trade standards or governments may enforce them through a combination of employment and commercial law. Proposed and practiced fair trade policies vary widely, ranging from the common prohibition of goods made using slave labour to minimum price support schemes such as those for coffee in the 1980s. Non-governmental organizations also play a role in promoting fair trade standards by serving as independent monitors of compliance with labeling requirements.[citation needed] As such, it is a form of Protectionism.

See also

- Accounting

- Advertising

- Bachelor of Commerce

- Business

- Capitalism

- Commercial law

Distribution (business)

- Wholesale

- Retailing

- Cargo

- Eco commerce

- Economic globalization

- Economy

- Electronic commerce

- Export

- Fair

- Finance

- Fishery

- Harvest

- Industry

- Import

- Laissez-faire

- Manufacturing

- Marketing

- Marketplace

- Mass production

- Master of Commerce

- Merchandising

- List of trading companies

Notes

^ ab Samuelson, P (1939). "The Gains from International Trade". The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science. 5 (2): 195–205. doi:10.2307/137133. JSTOR 137133..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Dollar, D; Kraay, A (2004). "Trade, Growth, and Poverty" (PDF). The Economic Journal. 114 (493): F22–F49. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.509.1584. doi:10.1111/j.0013-0133.2004.00186.x.

[dead link]

^ Munim, Ziaul Haque; Schramm, Hans-Joachim (2018). "The impacts of port infrastructure and logistics performance on economic growth: the mediating role of seaborne trade". Journal of Shipping and Trade. 3 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1186/s41072-018-0027-0.

^

Compare peddling and other types of retail trade:Hoffman, K. Douglas, ed. (2005). Marketing principles and best practices (3 ed.). Thomson/South-Western. p. 407. ISBN 9780324225198. Retrieved 2018-05-03.Five types of nonstore retailing will be discussed: street peddling, direct selling, mail-order, automatic-merchandising machine operators, and electronic shopping.

^ "Distribution Services". Foreign Agricultural Service. 2000-02-09. Archived from the original on 2006-05-15. Retrieved 2006-04-04.

^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Commerce". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 766.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Commerce". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 766.

^ Watson (2005), Introduction.

^ D Abulafia; O Rackham; M Suano (2008-07-31), The Mediterranean in History, Getty Publications, 1 Mar 2011, ISBN 978-1606060575, retrieved 2012-06-26

^ V Stefansson. Great Adventures and Explorations: From the Earliest Times to the Present As Told by the Explorers Themselves Kessinger Publishing, 30 May 2005

ISBN 1417990902 Retrieved 2012-06-26[dead link]

^ National Maritime Historical Society. Sea History, Issues 13-25 published by National Maritime Historical Society 1979. Retrieved 2012-06-26

^ Hans Biedermann, James Hulbert (trans.), Dictionary of Symbolism - Cultural Icons and the Meanings behind Them, p. 54.

^ (secondary)G G Lowder – Studies in volcanic petrology: I. Talasea, New Guinea. II. Southwest Utah University of California, 1970 Retrieved 2012-06-28

^ T Darvill (2011-03-23), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology, Oxford University Press, 10 Oct 2008, ISBN 978-0199534043, retrieved 2012-06-28

^ HIH Prince Mikasa no Miya Takahito – Essays on Anatolian Archaeology Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1993Retrieved 2012-06-16

^ Vernon Horace Rendall, ed. (1904). The Athenaeum. J. Francis. Retrieved 2012-06-09

^ Donald A. Mackenzie – Myths of Crete and Pre-Hellenic Europe – published 1917 –

ISBN 1605063754 Retrieved 2012-06-09

^ ab R L Smith (2008-07-31), Premodern Trade in World History, Taylor & Francis, 2009, ISBN 978-0415424769, retrieved 2012-06-15

^ P Singh – Neolithic cultures of western Asia Seminar Press, 20 Aug 1974

^ ab

J Robb (2007-07-23), The Early Mediterranean Village: Agency, Material Culture, and Social Change in Neolithic Italy, Cambridge University Press, 23 July 2007, ISBN 978-0521842419, retrieved 2012-06-11

^ P Goldberg, V T Holliday, C Reid Ferring – Earth Sciences and Archaeology Springer, 2001

ISBN 0306462796 Retrieved 2012-06-28

^ S L Dyson, R J Rowland – Archaeology And History In Sardinia From The Stone Age To The Middle Ages: Shepherds, Sailors, & Conquerors University of Pennsylvania – Museum of Archaeology, 2007

ISBN 1934536024 Retrieved 2012-06-28

^ Williams-Thorpe, O. (1995). "Obsidian in the Mediterranean and the Near East: A Provenancing Success Story". Archaeometry. 37 (2): 217–48. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1995.tb00740.x.

^ D Harper – etymology online Retrieved 2012-06-09

^ A. J. Andrea (2011-03-23), World History Encyclopedia, Volume 2, ABC-CLIO, 2011, ISBN 978-1851099306, retrieved 2012-06-11

^ T A H Wilkinson – Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategies, Society and Security[dead link]

^ secondary – [1] + [2] + [3] + [4] + [5]

^ (was secondary)Pliny the Elder (translated by J Bostock, H T Riley) (1857), The natural history of Pliny, Volume 6, H G Bohn 1857, ISBN 978-1851099306, retrieved 2012-06-11

^ ab E Blake; A B Knapp (2008-04-15), The Archaeology Of Mediterranean Prehistory, John Wiley & Sons, 21 Feb 2005, ISBN 978-0631232681, retrieved 2012-06-22

^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson – Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategies, Society and Security Routledge, 8 Aug 2001 Retrieved 2012-07-03[dead link]

^ D Collon – Near Eastern Seals University of California Press, 4 Dec 1990 Retrieved 2012-07-03

ISBN 0520073088 (Interpreting the past: British Museum PublicationsArmenian Research Center collection)

^ G Leick – The Babylonian world Routledge 2007 Retrieved 2012-07-03

ISBN 1134261284

^ S Bertman – Handbook To Life In Ancient Mesopotamia Oxford University Press, 7 Jul 2005 Retrieved 2012-07-03

ISBN 0195183649

^ L S Etheredge (2008-07-31), Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, The Rosen Publishing Group, 15 Jan 2011, ISBN 978-1615303298, retrieved 2012-06-15

^ M Dumper; B E Stanley (2007), Cities of The Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2007, ISBN 978-1576079195, retrieved 2012-06-28

^ B.Gascoigne et al – History World .net

^ Ivan Dikov (July 12, 2015). "Bulgarian Archaeologists To Start Excavations of Ancient Greek Emporium in Thracians' Odrysian Kingdom". Archaeology in Bulgaria. Retrieved 28 October 2010.An emporium (in Latin; “emporion" in Greek) was a settlement reserved as a trading post, usually for the Ancient Greeks, on the territory of another ancient nation, in this case the Ancient Thracian Odrysian Kingdom (5th century BC – 1st century AD), the most powerful Thracian state.

^ Pax Romana let average villagers throughout the Empire conduct day to day affairs without fear of armed attack.

^ P D Curtin – Cross-Cultural Trade in World History Cambridge University Press, 25 May 1984

ISBN 0521269318 Retrieved 2012-06-25

^ N. O. Brown – Hermes the Thief: The Evolution of a Myth SteinerBooks, 1 Mar 1990

ISBN 0940262266 Retrieved 2012-06-25

^ D Sacks, O Murray – A Dictionary of the Ancient Greek World Oxford University Press, 6 Feb 1997

ISBN 0195112067 Retrieved 2012-06-26

^ Alexander S. Murray – Manual of Mythology Wildside Press LLC, 30 May 2008

ISBN 1434470288 Retrieved 2012-06-25

^ John R. Rice – Filled With the Spirit Sword of the Lord Publishers, 1 Aug 2000

ISBN 087398255X Retrieved 2012-06-25

^ Johannes Hasebroek – Trade and Politics in Ancient Greece Biblo & Tannen Publishers, 1 Mar 1933 Retrieved 2012-07-04

ISBN 0819601500

^ Cambridge dictionaries online

^ Moshe, Gil. "The Rādhānite Merchants and the Land of Rādhān". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 17 (3): 299.

^ AS Greenberg – J. Pat. Off. Soc'y, 1951 – HeinOnline

^ "Aztec Hoe Money". National Museum of American History. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

^ K G Hirth – American Antiquity Vol. 43, No. 1 (Jan., 1978), pp. 35–45 Retrieved 2012-06-28

^ McGrail, Sean (2001). Boats of the World : From the Stone Age to Medieval Times. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

^ Poole, Austin Lane (1958). Medieval England. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

^ Beckwith (2011), p. xxiv.

^ Price theory Milton Friedman

^ (secondary) British Broadcasting Corporation – history

^ (secondary) M Smith – V. Gollancz, 1996

ISBN 0575061502

^ "EU position in world trade". European Commission. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

^ Nomani & Rahnema (1994), p. ?. "I want nine out of ten people from my Ummah (nation) as traders" and "Trader, who did trading in truth, and sold the right quantity and quality of goods, he will stand along Prophets and Martyrs, on Judgment day".

^ "O ye who believe! Eat not up your property among yourselves in vanities; but let there be among you traffic and trade by mutual good-will." Quran 4:29 and "Allah has allowed trading and forbidden usury." Quran 2:275

^

Leviticus 19:13

^ Leviticus 19:35

^ Gold was an especially common form of early money, as described in Davies (2002).

^ Division, US Census Bureau Foreign Trade. "Foreign Trade: Data". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

^ "U.S.–Cuba Relations". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

^ "Should trade be considered a human right?". COPLA. 9 December 2008. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trade. |

Beckwith, Christopher I (2011) [2009]. Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15034-5.

Bernstein, William (2008). A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-4416-4.

Davies, Glyn (2002) [1995]. Ideas: A History of Money from Ancient Times to the Present Day. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1773-0.

Nomani, Farhad; Rahnema, Ali (1994). Islamic Economic Systems. New Jersey: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-85649-058-0.

Paine, Lincoln (2013). The Sea and Civilisation: a Maritime History of the World. Atlantic. (Covers sea-trading over the whole world from ancient times.)

Watson, Peter (2005). Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention from Fire to Freud. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-621064-3.

External links

| Look up trade in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Agritrade Resource material on trade by ACP countries

World Bank's World Integrated Trade Solution provides summary trade statistics and custom query features

World Bank's Preferential Trade Agreement Database