Buffalo Ridge

Buffalo Ridge is a large expanse of rolling hills in the southeastern part of the larger Coteau des Prairies. It stands 1,995 feet (608 m) above sea level. The Buffalo Ridge is sixty miles long and runs through Lincoln County, Pipestone County, Murray County, Nobles County, and Rock County in the southwest corner of Minnesota.

Because of its high altitude and high average wind speed, Buffalo Ridge has been transformed into a place for creating alternative energy. Currently, over 200 wind turbines stand along the Buffalo Ridge.

Buffalo Ridge is located within the Minnesota portion of the Coteau des Prairies, a highland represented by the light areas in this shaded relief image of southwestern Minnesota.

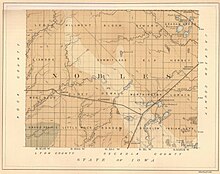

High portion of the Buffalo Ridge can be seen on this Nobles County map from an 1882 Geological Report[1]

Contents

1 Geology

2 Climate

2.1 Tornado of 1992

3 Geography

3.1 Hole in the Mountain Prairie

4 Wind farms

5 See also

6 References

7 Works cited

8 External links

Geology

Buffalo Ridge is commonly considered the elevated land extending through Lincoln, Lyon, Pipestone, Murray, Rock, and Nobles counties. It is a drainage divide separating the watersheds of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers.

Buffalo Ridge is part of the inner coteau and is the highest point of the Coteau des Prairies in Minnesota.[2] Its bedrock is formed of Cretaceous shale, sandstone and clay that lie above the pinkish-red Upper Precambrian Sioux Quartzite.[3] These units are covered in most areas by thick deposits of glacial drift, which consist of up to 800 feet (244 m) of pre-Wisconsin age glacial till (generally considered Kansas drift) left after the glaciers receded. The inner coteau is made up of extremely stream-eroded glacial deposits of pre-Wisconsin glacial drift, which is then covered by a 6 to 15 foot (1.8 to 4.6 m) thick deposit of a wind-blown silt called loess.[2] This covering results in the creation of an area with long, gently sloping hills. Loess is an easily eroded material, and because of this there are few lakes and wetlands in the inner coteau area. Loess however promotes well established dendritic drainage networks, the majority of which flow into the Missouri River and Minnesota River systems. Loamy, well-drained soils like Mollisols-Aquolls and Udolls containing Borolls and Ustolls dominate the soils of the inner coteau.[2] On the areas of eroded glacial deposits, dry prairie and moist prairie soils like Cummins and Grigal are present. These soil types, along with the temperate climate,[4] combine to make perfect growing conditions for tallgrass prairie, which once covered almost the entire inner coteau.

Buffalo Ridge

Climate

Buffalo Ridge has a midlatitude continental climate with an average twenty-four to twenty-seven inches (0.6 to 0.7 m) of precipitation per year and thirty-six to forty inches (0.9 to 1.0 m) of snowfall per winter. The average spring thaw is around April 5 and the spring green-up generally occurs between May 1 and May 10. Peaking fall colors tend to occur around October 20 and there are generally forty to fifty thunderstorm days per year.[5]

Tornado of 1992

On the weekend of June 13, 1992 a large storm developed over the Northern Great Plains, resulting in severe weather in western South Dakota. On June 16, another storm struck eastern South Dakota and southwestern Minnesota destroying over one hundred homes and businesses. These supercells created many large damaging tornadoes. The first tornado formed in Charles Mix County and moved toward Mitchell, South Dakota. The second formed in Miner County, South Dakota and the third formed south of Pierre, South Dakota both causing considerable property damage. The fourth tornado formed near the unincorporated town of Leota in southwest Minnesota, spawning a "maxi" tornado that stayed on the ground for almost an hour and a half and did substantial damage to the cities of Chandler and Lake Wilson, Minnesota. In Chandler, the property damage was estimated at over fifteen million dollars. This tornado was classified as an F5 tornado on the Fujita Scale and turned out to be the only F5 tornado documented in the United States in 1992. Another tornado formed in South Dakota later in the day and made its way to Minnesota where it struck the town of Chandler for the second time, along with Colton and Dell Rapids.

Geography

Before the settlers arrived and developed the towns on and surrounding Buffalo Ridge, the Dakota Native Americans inhabited the area. It was the Dakota who created intricate pipes out of the quartzite in the Buffalo Ridge area, which today are displayed at Pipestone National Monument.

The land on Buffalo Ridge is mostly privately owned farmland. However, there is also an 800-acre (3,200,000 m2) tall grass prairie conservancy which is owned and protected by The Nature Conservancy.

Hole in the Mountain Prairie

Hole in the Mountain Prairie is a nature reserve created by the Nature Conservancy. It is located on the outer edge of Buffalo Ridge and is the headwaters of Flandreau Creek. It was created to preserve the diminishing tallgrass prairie and the insects and animals native to tallgrass prairies. In the past the area had been used as a grazing area for cattle and sheep. The result being the almost extinction of the tallgrass prairie. Today the Nature Conservancy manages the Hole in the Mountain with controlled burning which have led to a remarkable recovery of the native prairie vegetation.[6]

Wind farms

A number of wind farms are sited on the ridge because of the windy conditions in the area. Nobles Wind Farm, Buffalo Ridge Wind Farm, and Fenton Wind Farm are several of them.

Coordinates: 43°58′49″N 96°00′38″W / 43.9802442°N 96.0105766°W / 43.9802442; -96.0105766[7]

See also

- Wind power

- Wind farm

- Wind power in the United States

- List of large wind farms

- Venturi effect

References

^ The Geology of Minnesota Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

^ abc DNR, Minnesota DNR, http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/ecs/251Bc/index.html.

^ Anderson RR (1987) Precambrian Sioux Quartzite at Gitchie Manitou State Preserve, Iowa. Centennial Field Guide Volume 3: North-Central Section of the Geological Society of America: Vol. 3, No. 0 pp. 77–80. http://www.gsajournals.org/perlserv/?request=res-loc&uri=urn%3Aap%3Apdf%3Adoi%3A10.1130%2F0-8137-5403-8.77

^ USGS, Northern Prairie Research Center, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-09-29. Retrieved 2007-04-27.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link).mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}.

^ Paul Douglas, "Prairie Skies" (Voyager Press Inc., 1990)

^ Nature Conservancy, "Hole-in-the-Mountain Prairie", http://www.nature.org/wherewework/northamerica/states/minnesota/preserves/art7109.html

^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Buffalo Ridge

Works cited

- "Buffalo Ridge Wind Towers." HendricksMN. 2004. Hendricks, Minnesota. 22 Apr 2007 <https://web.archive.org/web/20070416072730/http://hendricksmn.com/wind_towers.html%3E.

- Dieter, Charles and Higgins, Kenneth and Osbourn, Robert and Usgaard, Richard. "Bird Flight Characteristics Near Wind Turbines in Minnesota." The American Midland Naturalist 139Jan 1998 29-38. 26 Apr 2007 <http://www.bioone.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1674%2F0003-0031(1998)139%5B0029%3ABFCNWT%5D2.0.CO%3B2>.

- Douglas, Paul. Prairie Skies. Voyageur Press Inc., 1990.

- "Regional Landscape Ecosystems of Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin." Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 03 Aug 2006. USGS. 22 Apr 2007 <https://web.archive.org/web/20060929083936/http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/habitat/rlandscp/s2-2-1.htm%3E.

- Peterson, Dean and Gary Richter. Buffalo Ridge Tornado June 16, 1992. Walsworth Publ. 1994.

- "Wind Power on the Buffalo Ridge." The City of Lake Benton, Minnesota. govoffice.com. 22 Apr 2007 <http://www.lakebentonminnesota.com/index.asp?Type=NONE&SEC={B62CE668-CE41-4427-BBCF-D3D873A5A3C9}>.

External links

- Western EcoSystems Technology website