Terra Sirenum

MOLA map showing boundaries of Terra Sirenum and other regions

MOLA map showing boundaries of Terra Sirenum near the south pole and other regions

Terra Sirenum is named after the Sirens who were birds with the heads of girls. In the Odyssey these girls captured passing seamen and killed them.[1]

Terra Sirenum is a large region in the southern hemisphere of the planet Mars. It is centered at 39°42′S 150°00′W / 39.7°S 150°W / -39.7; -150 and covers 3900 km at its broadest extent. It covers latitudes 10 to 70 South and longitudes 110 to 180 W.[2] Terra Sirenum is an upland area notable for massive cratering including the large Newton Crater. Terra Sirenum is in the Phaethontis quadrangle and the Memnonia quadrangle of Mars. A low area in Terra Sirenum is believed to have once held a lake that eventually drained through Ma'adim Vallis.[3][4][5]

Contents

1 Chloride deposits

2 Inverted relief

3 Craters

3.1 List of craters

4 Martian gullies

5 Tongue-shaped glaciers

6 Possible pingos

7 Concentric crater fill

8 Liu Hsin Crater features

9 Magnetic stripes and plate tectonics

10 Other features

11 Interactive Mars map

12 See also

13 References

14 Recommended reading

15 External links

Chloride deposits

Evidence of deposits of chloride based minerals in Terra Sirenum was discovered by the 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter's Thermal Emission Imaging System in March 2008. The deposits are approximately 3.5 to 3.9 billion years old. This suggests that near-surface water was widespread in early Martian history, which has implications for the possible existence of Martian life.[6][7] Besides finding chlorides, MRO discovered iron/magnesium smectites which are formed from long exposure in water.[8]

Based on chloride deposits and hydrated phyllosilicates, Alfonso Davila and others believe there is an ancient lakebed in Terra Sirenum that had an area of 30,000 km2 and was 200 meters deep. Other evidence that supports this lake are normal and inverted channels like ones found in the Atacama desert.[9]

Inverted relief

Some areas of Mars show inverted relief, where features that were once depressions, like streams, are now above the surface. It is believed that materials like large rocks were deposited in low-lying areas. Later, erosion (perhaps wind which can't move large rocks) removed much of the surface layers, but left behind the more resistant deposits. Other ways of making inverted relief might be lava flowing down a stream bed or materials being cemented by minerals dissolved in water. On Earth, materials cemented by silica are highly resistant to all kinds of erosional forces. Examples of inverted channels on Earth are found in the Cedar Mountain Formation near Green River, Utah. Inverted relief in the shape of streams are further evidence of water flowing on the Martian surface in past times.[10]

CTX image of craters with black box showing location of next image.

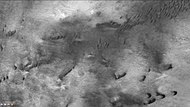

Image from previous photo of a curved ridge that may be an old stream that has become inverted. Image taken with HiRISE under the HiWish program.

Craters

List of craters

The following is a list of craters in Terra Sirenum. The crater's central location is of the feature, craters that its central location is in another feature are listed by eastern, western, northern or southern part.

| Name | Location | Quadrangle(s) | Diameter | Year of approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avire | 40°49′S 159°46′W / 40.82°S 159.76°W / -40.82; -159.76 | Phaethontis | 6.85 km | 2008 |

| Belyov | Phaethontis | |||

Bernard | 23°36′S 154°18′W / 23.6°S 154.3°W / -23.6; -154.3 | Memnonia | 121 km | |

| Bunnik | Phaethontis | |||

Burton | 14°06′S 156°24′W / 14.1°S 156.4°W / -14.1; -156.4 | Memnonia | 123 km | 1973 |

Charlier | 68°34′S 168°40′W / 68.56°S 168.67°W / -68.56; -168.67 | Mare Australe | 106.28 km | 1973 |

Clark | Phaethontis | |||

| Cobres | Memnonia | |||

Columbus | 29°48′S 166°06′W / 29.8°S 166.1°W / -29.8; -166.1 | Memnonia | 119 km | |

Comas Sola | 19°35′S 168°31′W / 19.59°S 168.51°W / -19.59; -168.51 | Memnonia | 120.24 km | 1973 |

Copernicus | 48°48′S 168°48′W / 48.8°S 168.8°W / -48.8; -168.8 | Phaethontis | 300 km | 1973 |

Cross1 | Memnonia, Phaethontis | |||

| Dechu | 42°15′S 157°59′W / 42.25°S 157.99°W / -42.25; -157.99 | Phaethontis | 22 km | 2018 |

Dejnev | 25°30′S 164°48′W / 25.5°S 164.8°W / -25.5; -164.8 | Memnonia | 152 km | 1985 |

| Dunkassa | Phaethontis | |||

Ejriksson | 19°24′S 173°54′W / 19.4°S 173.9°W / -19.4; -173.9 | Memnonia | 49 km | 1967 |

Eudoxus | 44°54′S 147°30′W / 44.9°S 147.5°W / -44.9; -147.5 | Phaethontis | 98 km | 1973 |

| Galap | Phaethontis | |||

| Gratteri | Memnonia | |||

| Henbury | Phaethontis | |||

| Kamnik | Phaethontis | |||

Keeler | 61°00′S 151°18′W / 61°S 151.3°W / -61; -151.3 | Phaethontis | 95 km | 1973 |

| Kibuye | Memnonia | |||

Koval'sky | Memnonia, Phaethontis | 297 km | 1973 | |

Kuiper | 57°24′S 157°18′W / 57.4°S 157.3°W / -57.4; -157.3 | Phaethontis | 87 km | 1973 |

| Langtang | Phaethontis | |||

Li Fan | 47°12′S 153°12′W / 47.2°S 153.2°W / -47.2; -153.2 | Phaethontis | 104.8 km | 1973 |

Liu Hsin | 53°36′S 171°36′W / 53.6°S 171.6°W / -53.6; -171.6 | Phaethontis | 137 km | 1973 |

Magelhaens | 32°22′S 194°41′W / 32.36°S 194.68°W / -32.36; -194.68 | Phaethontis | 105 km | |

| Marca | Memnonia | |||

Mariner | 35°06′S 164°30′W / 35.1°S 164.5°W / -35.1; -164.5 | Phaethintis | 170 km | 1967 |

Millman | Phaethontis | |||

Nansen | 50°18′S 140°36′W / 50.3°S 140.6°W / -50.3; -140.6 | Phaethontis | 81 km | 1967 |

| Naruko | Phaethontis | |||

Newton | 40°48′S 158°06′W / 40.8°S 158.1°W / -40.8; -158.1 | Phaethontis | 298 km | 1973 |

| Niquero | Phaethontis | |||

Nordenskiöld | Phaethontis | |||

| Palikir | 41°34′S 158°52′W / 41.57°S 158.86°W / -41.57; -158.86 | Phaethontis | 15.57 km | 2011 |

Pickering | Phaethontis | 1973 | ||

Ptolemaeus | 48°13′S 157°36′W / 48.21°S 157.6°W / -48.21; -157.6 | Phaethontis | 165 km | 1973 |

| Reutov | Phaethontis | |||

| Selevac | Phaethontis | |||

Suess | 67°06′S 178°36′W / 67.1°S 178.6°W / -67.1; -178.6 | Mare Australe | 71.9 km | 1973 |

| Sitrah | Phaethontis | |||

| Taltal | Phaethontis | |||

| Triolet | Phaethontis | |||

Trumpler | Phaethontis | |||

| Tyutaram | Phaethontis | 2013 | ||

Very | 49°36′S 177°06′W / 49.6°S 177.1°W / -49.6; -177.1 | Phaethontis | 114.8 km | 1973 |

Williams | 18°42′S 164°18′W / 18.7°S 164.3°W / -18.7; -164.3 | Memnonia | 123.2 km | 1973 |

Wright | 58°54′S 151°00′W / 58.9°S 151°W / -58.9; -151 | Phaethontis | 113.7 km | 1973 |

| Yaren | Phaethontis |

Martian gullies

Terra Sirenum is the location of many Martian gullies that may be due to recent flowing water. Some are found in the Gorgonum Chaos[11][12] and in many craters near the large craters Copernicus and Newton.[13][14] Gullies occur on steep slopes, especially on the walls of craters. Gullies are believed to be relatively young because they have few, if any craters. Moreover, they lie on top of sand dunes which themselves are considered to be quite young. Usually, each gully has an alcove, channel, and apron. Some studies have found that gullies occur on slopes that face all directions,[15] others have found that the greater number of gullies are found on poleward facing slopes, especially from 30-44 S.[16][17]

Although many ideas have been put forward to explain them,[18] the most popular involve liquid water coming from an aquifer, from melting at the base of old glaciers, or from the melting of ice in the ground when the climate was warmer.[19][20] Because of the good possibility that liquid water was involved with their formation and that they could be very young, scientists are excited. Maybe the gullies are where we should go to find life.

There is evidence for all three theories. Most of the gully alcove heads occur at the same level, just as one would expect of an aquifer. Various measurements and calculations show that liquid water could exist in aquifers at the usual depths where gullies begin.[21] One variation of this model is that rising hot magma could have melted ice in the ground and caused water to flow in aquifers. Aquifers are layer that allow water to flow. They may consist of porous sandstone. The aquifer layer would be perched on top of another layer that prevents water from going down (in geological terms it would be called impermeable). Because water in an aquifer is prevented from going down, the only direction the trapped water can flow is horizontally. Eventually, water could flow out onto the surface when the aquifer reaches a break—like a crater wall. The resulting flow of water could erode the wall to create gullies.[22] Aquifers are quite common on Earth. A good example is "Weeping Rock" in Zion National Park Utah.[23]

As for the next theory, much of the surface of Mars is covered by a thick smooth mantle that is thought to be a mixture of ice and dust.[24][25][26] This ice-rich mantle, a few yards thick, smoothes the land, but in places it has a bumpy texture, resembling the surface of a basketball. The mantle may be like a glacier and under certain conditions the ice that is mixed in the mantle could melt and flow down the slopes and make gullies.[27][28][29] Because there are few craters on this mantle, the mantle is relatively young. An excellent view of this mantle is shown below in the picture of the Ptolemaeus Crater Rim, as seen by HiRISE.[30]

The ice-rich mantle may be the result of climate changes.[31] Changes in Mars's orbit and tilt cause significant changes in the distribution of water ice from polar regions down to latitudes equivalent to Texas. During certain climate periods water vapor leaves polar ice and enters the atmosphere. The water comes back to ground at lower latitudes as deposits of frost or snow mixed generously with dust. The atmosphere of Mars contains a great deal of fine dust particles. Water vapor will condense on the particles, then fall down to the ground due to the additional weight of the water coating. When Mars is at its greatest tilt or obliquity, up to 2 cm of ice could be removed from the summer ice cap and deposited at midlatitudes. This movement of water could last for several thousand years and create a snow layer of up to around 10 meters thick.[32][33] When ice at the top of the mantling layer goes back into the atmosphere, it leaves behind dust, which insulating the remaining ice.[34] Measurements of altitudes and slopes of gullies support the idea that snowpacks or glaciers are associated with gullies. Steeper slopes have more shade which would preserve snow.[16][35]

Higher elevations have far fewer gullies because ice would tend to sublimate more in the thin air of the higher altitude.[36]

The third theory might be possible since climate changes may be enough to simply allow ice in the ground to melt and thus form the gullies. During a warmer climate, the first few meters of ground could thaw and produce a "debris flow" similar to those on the dry and cold Greenland east coast.[37] Since the gullies occur on steep slopes only a small decrease of the shear strength of the soil particles is needed to begin the flow. Small amounts of liquid water from melted ground ice could be enough.[38][39] Calculations show that a third of a mm of runoff can be produced each day for 50 days of each Martian year, even under current conditions.[40]

CTX image of the next image showing a wide view of the area. Since the hill is isolated it would be difficult for an aquifer to develop. Rectangle shows the approximate location of the next image.

Gully on mound as seen by Mars Global Surveyor, under the Public Target Program. Images of gullies on isolated peaks, like this one, are difficult to explain with the theory of water coming from aquifers because aquifers need large collecting areas.

Another view of the previous gully on a mound. This one is with HiRISE, under the HiWish program. This view shows most of the apron and two old glaciers associated with it. All that is left of the glaciers are terminal moraines.

MOLA context image for the series of three images to follow of gullies in a trough and nearby crater.

Gullies in a trough and nearby crater, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. Scale bar is 500 meters long.

Close-up of gullies in crater, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program.

Close-up of gullies in trough, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. These are some of the smaller gullies visible on Mars.

HiRISE image, taken under HiWish program, of gullies in a crater in Terra Sirenum.

Gullies with remaines of a former glacier in crater in Terra Sirenum, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Gullies in a crater in Terra Sirenum, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish Program.

Close-up of gully showing multiple channels and patterned ground, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program.

Gullies in crater in Phaethontis quadrangle, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Gullies in crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Location is Phaethontis quadrangle.

Close up of gullies in crater showing channels within larger valleys and curves in channels. These characteristics suggest they were made by flowing water. Note: this is an enlargement of the previous image by HiRISE under HiWish program. Location is Phaethontis quadrangle.

Close up of gully network showing branched channels and curves; these characteristics suggest creation by a fluid. Note: this is an enlargement of a previous wide view of gullies in a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Location is Phaethontis quadrangle.

Gullies in two levels of a crater wall, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Gullies at two levels suggests they were not made with an aquifer, as was first suggested. Location is Phaethontis quadrangle.

Image of gullies with main parts labeled. The main parts of a Martian gully are alcove, channel, and apron. Since there are no craters on this gully, it is thought to be rather young. Picture was taken by HiRISE under HiWish program. Location is Phaethontis quadrangle.

Close-up of gully aprons showing they are free of craters; hence very young. Location is Phaethontis quadrangle. Picture was taken by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Tongue-shaped glaciers

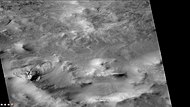

Tongue-shaped glacier, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. Location is Phaethontis quadrangle.

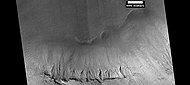

Wide view of several tongue-shaped glaciers on wall of crater, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. The glaciers are of different sizes and lie at different levels. Some of these are greatly enlarged in pictures which follow.

Close-up of the snouts of two glaciers from the previous image, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. These are towards the bottom left of the previous image.

Close-up of small glaciers from a previous image, as seen by HiRISE under the HiWish program. Some of these glaciers seem to be just starting to form.

Close-up of the edge of one of the glaciers on the bottom of the wide view from a previous image Picture was taken by HiRISE under the HiWish program.

Possible pingos

The radial and concentric cracks visible here are common when forces penetrate a brittle layer, such as a rock thrown through a glass window. These particular fractures were probably created by something emerging from below the brittle Martian surface. Ice may have accumulated under the surface in a lens shape; thus making these cracked mounds. Ice being less dense than rock, pushed upwards on the surface and generated these spider web-like patterns. A similar process creates similar sized mounds in arctic tundra on Earth. Such features are called “pingos,”, an Inuit word.[41] Pingos would contain pure water ice; thus they could be sources of water for future colonists of Mars.

Possible pingo, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Possible pingos with scale, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Close view of possible pingo with scale, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Example of a pingo on Earth. On Earth the ice that caused the pingo would melt and fill the fractures with water; on Mars the ice would turn into a gas in the thin Martian atmosphere.

Concentric crater fill

Concentric crater fill, like lobate debris aprons and lineated valley fill, is believed to be ice-rich.[42] Based on accurate topography measures of height at different points in these craters and calculations of how deep the craters should be based on their diameters, it is thought that the craters are 80% filled with mostly ice.[43][44][45][46] That is, they hold hundreds of meters of material that probably consists of ice with a few tens of meters of surface debris.[47][48] The ice accumulated in the crater from snowfall in previous climates.[49][50][51] Recent modeling suggests that concentric crater fill develops over many cycles in which snow is deposited, then moves into the crater. Once inside the crater shade and dust preserve the snow. The snow changes to ice. The many concentric lines are created by the many cycles of snow accumulation. Generally snow accumulates whenever the axial tilt reaches 35 degrees.[52]

Crater showing concentric crater fill, as seen by CTX (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter). Location is Phaethontis quadrangle.

Close-up view of concentric crater fill, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Note: this is an enlargement of previous image of a concentric crater. Location is Phaethontis quadrangle.

Wide view of concentric crater fill, as seen by CTX Location is the Phaethontis quadrangle.

Concentric crater fill, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Location is the Phaethontis quadrangle.

Close, color view of concentric crater fill, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Location is the Phaethontis quadrangle.

Liu Hsin Crater features

Liu Hsin Crater, as seen by CTX camera (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter).

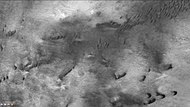

Dunes in Liu Hsin Crater, as seen by CTX camera (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter). Dark lines are dust devil tracks. Note: this is an enlargement of a previous image of Liu Sin Crater.

Dust devil tracks in Liu Hsin Crater, as seen by CTX camera (on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter). Gullies can also be seen on the crater wall, near the bottom of picture. Note: this is an enlargement of a previous image of Liu Sin Crater.

Gullies in Liu Hsin Crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Curved lines on crater floor may be remains of old glaciers.

Magnetic stripes and plate tectonics

The Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) discovered magnetic stripes in the crust of Mars, especially in the Phaethontis and Eridania quadrangles (Terra Cimmeria and Terra Sirenum).[53][54] The magnetometer on MGS discovered 100 km wide stripes of magnetized crust running roughly parallel for up to 2000 km. These stripes alternate in polarity with the north magnetic pole of one pointing up from the surface and the north magnetic pole of the next pointing down.[55] When similar stripes were discovered on Earth in the 1960s, they were taken as evidence of plate tectonics. Researchers believe these magnetic stripes on Mars are evidence for a short, early period of plate tectonic activity. When the rocks became solid they retained the magnetism that existed at the time. A magnetic field of a planet is believed to be caused by fluid motions under the surface.[56][57][58] However, there are some differences, between the magnetic stripes on Earth and those on Mars. The Martian stripes are wider, much more strongly magnetized, and do not appear to spread out from a middle crustal spreading zone.

Because the area containing the magnetic stripes is about 4 billion years old, it is believed that the global magnetic field probably lasted for only the first few hundred million years of Mars' life, when the temperature of the molten iron in the planet's core might have been high enough to mix it into a magnetic dynamo. There are no magnetic fields near large impact basins like Hellas. The shock of the impact may have erased the remnant magnetization in the rock. So, magnetism produced by early fluid motion in the core would not have existed after the impacts.[59]

When molten rock containing magnetic material, such as hematite (Fe2O3), cools and solidifies in the presence of a magnetic field, it becomes magnetized and takes on the polarity of the background field. This magnetism is lost only if the rock is subsequently heated above a particular temperature (the Curie point which is 770 °C for iron). The magnetism left in rocks is a record of the magnetic field when the rock solidified.[60]

Other features

Channel, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program Streamlined shapes are indicated with arrows. Location is the Phaethontis quadrangle.

Possible chloride deposits in Terra Sirenum

Layers in crater wall, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Area in box is enlarged in the next image.

Enlargement from previous image, showing many thin layers. Note that the layers do not seem to be formed from rocks. They may be all that is left of a deposit that once filled the crater. Image was taken with HiRISE, under HiWish program.

Surface of crater floor, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Surface of crater floor showing details from image taken with HiRISE, under HiWish program. This may be a transition from one type of structure to a different, maybe due to erosion.

Surface showing large hollows of unknown origin, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. The hollows may be the result of large amounts of ice leaving the ground.

Close-up of surface with large hollows, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Layers in mantle, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Oxbow lake, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Troughs on the floor of Bernard Crater showing many boulders, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Troughs on the floor of Bernard Crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Large pits in Sirenum Fossae, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Lava flow. Lava flow stopped when it encountered the higher ground of a mound. Picture was taken with HiRISE under HiWish program.

HiRISE image showing smooth mantle covering parts of a crater in the Phaethontis quadrangle. Along the outer rim of the crater, the mantle is displayed as layers. This suggests that the mantle was deposited multiple times in the past. Picture was taken with HiRISE under HiWish program. The layers are enlarged in the next image.

Enlargement of previous image of mantle layers. Four to five layers are visible. Location is the Phaethontis quadrangle.

Surface showing appearance with and without mantle covering, as seen by HiRISE, under the HiWish program. Location is Terra Sirenum in Phaethontis quadrangle.

Interactive Mars map

See also

- Climate of Mars

- Geology of Mars

- Glaciers on Mars

- Groundwater on Mars

- Impact crater

- List of craters on Mars

- Martian gullies

References

^ Blunck, J. 1982. Mars and its Satellites. Exposition Press. Smithtown, N.Y.

^ http://www.itouchmap.com/?r=marsfeatures&z=7238

^ Irwin, R, et al. 2002. Geomorphology of Ma'adim Vallis, Mars and associated paleolake basins. J. Geophys. Res. 109(E12): doi:10.1029/2004JE002287

^ Michael H. Carr (2006). The surface of Mars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87201-0. Retrieved 21 March 2011..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ https://www.uahirise.org/ESP_050948_1430

^ Osterloo; Hamilton, VE; Bandfield, JL; Glotch, TD; Baldridge, AM; Christensen, PR; Tornabene, LL; Anderson, FS; et al. (2008). "Chloride-Bearing Materials in the Southern Highlands of Mars". Science. 319 (5870): 1651–1654. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1651O. doi:10.1126/science.1150690. PMID 18356522.

^ "NASA Mission Finds New Clues to Guide Search for Life on Mars". 2008-03-20. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

^ Murchie, S. et al. 2009. A synthesis of Martian aqueous mineralogy after 1 Mars year of observations from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Journal of Geophysical Research: 114.

^ Davila, A. et al. 2011. A large sedimentary basin in the Terra Sirenum region of the southern highlands of Mars. Icarus. 212: 579-589.

^ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSP_006770_1760

^ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSP_004071_1425

^ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSP_001948_1425

^ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSP_004163_1375

^ U.S. department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey, Topographic Map of the Eastern Region of Mars M 15M 0/270 2AT, 1991

^ Edgett, K. et al. 2003. Polar-and middle-latitude martian gullies: A view from MGS MOC after 2 Mars years in the mapping orbit. Lunar Planet. Sci. 34. Abstract 1038.

^ ab http://www.planetary.brown.edu/pdfs/3138.pdf

^ Dickson, J. et al. 2007. Martian gullies in the southern mid-latitudes of Mars Evidence for climate-controlled formation of young fluvial features based upon local and global topography. Icarus: 188. 315-323

^ http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/Aug03/MartianGullies.html

^ Heldmann, J. and M. Mellon. Observations of martian gullies and constraints on potential formation mechanisms. 2004. Icarus. 168: 285-304.

^ Forget, F. et al. 2006. Planet Mars Story of Another World. Praxis Publishing. Chichester, UK.

^ Heldmann, J.; Mellon, M. (2004). "Observations of martian gullies and constraints on potential formation mechanisms". Icarus. 168 (2): 285–304. Bibcode:2004Icar..168..285H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2003.11.024.

^ http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/mars_aquifer_041112.html

^ Harris, A and E. Tuttle. 1990. Geology of National Parks. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Dubuque, Iowa

^ Malin, M. and K. Edgett. 2001. Mars Global Surveyor Mars Orbiter Camera: Interplanetary cruise through primary mission. J. Geophys. Res.: 106> 23429-23570

^ Mustard, J. et al. 2001. Evidence for recent climate change on Mars from the identification of youthful near-surface ground ice. Nature: 412. 411-414.

^ Carr, M. 2001. Mars Global Surveyor observations of fretted terrain. J. Geophys. Res.: 106. 23571-23595.

^ http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15702457?

^ http://www.pnas.org/content/105/36/13258.full

^ Head, J. et al. 2008. Formation of gullies on Mars: Link to recent climate history and insolation microenvironments implicate surface water flow origin. PNAS: 105. 13258-13263.

^ Christensen, P. 2003. Formation of recent martian gullies through melting of extensive water-rich snow deposits. Nature: 422. 45-48.

^ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2008/03/080319-mars-gullies_2.html

^ Jakosky B. and M. Carr. 1985. Possible precipitation of ice at low latitudes of Mars during periods of high obliquity. Nature: 315. 559-561.

^ Jakosky, B. et al. 1995. Chaotic obliquity and the nature of the Martian climate. J. Geophys. Res.: 100. 1579-1584.

^ MLA NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2003, December 18). Mars May Be Emerging From An Ice Age. ScienceDaily. Retrieved February 19, 2009, from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2003/12/031218075443.htmAds[permanent dead link] by GoogleAdvertise

^ Dickson, J. et al. 2007. Martian gullies in the southern mid-latitudes of Mars Evidence for climate-controlled formation of young fluvial features based upon local and global topography. Icarus: 188. 315-323.

^ Hecht, M. 2002. Metastability of liquid water on Mars. Icarus: 156. 373-386.

^ Peulvast, J. Physio-Geo. 18. 87-105.

^ Costard, F. et al. 2001. Debris Flows on Mars: Analogy with Terrestrial Periglacial Environment and Climatic Implications. Lunar and Planetary Science XXXII (2001). 1534.pdf

^ http://www.spaceref.com:16090/news/viewpr.html?pid=7124[permanent dead link],

^ Clow, G. 1987. Generation of liquid water on Mars through the melting of a dusty snowpack. Icarus: 72. 93-127.

^ http://www.uahirise.org/ESP_046359_1250

^ Levy, J. et al. 2009. Concentric crater fill in Utopia Planitia: History and interaction between glacial "brain terrain" and periglacial processes. Icarus: 202. 462-476.

^ Levy, J., J. Head, D. Marchant. 2010. Concentric Crater fill in the northern mid-latitudes of Mars: Formation process and relationships to similar landforms of glacial origin. Icarus 2009, 390-404.

^ Levy, J., J. Head, J. Dickson, C. Fassett, G. Morgan, S. Schon. 2010. Identification of gully debris flow deposits in Protonilus Mensae, Mars: Characterization of a water-bearing, energetic gully-forming process. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 294, 368–377.

^ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/ESP_032569_2225

^ Garvin, J., S. Sakimoto, J. Frawley. 2003. Craters on Mars: Geometric properties from gridded MOLA topography. In: Sixth International Conference on Mars. July 20–25, 2003, Pasadena, California. Abstract 3277.

^ Garvin, J. et al. 2002. Global geometric properties of martian impact craters. Lunar Planet. Sci: 33. Abstract # 1255.

^ http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA09662

^ Kreslavsky, M. and J. Head. 2006. Modification of impact craters in the northern planes of Mars: Implications for the Amazonian climate history. Meteorit. Planet. Sci.: 41. 1633-1646

^ Madeleine, J. et al. 2007. Exploring the northern mid-latitude glaciation with a general circulation model. In: Seventh International Conference on Mars. Abstract 3096.

^ http://hirise.lpl.arizona.edu/PSP_002917_2175

^ Fastook, J., J.Head. 2014. Concentric crater fill: Rates of glacial accumulation, infilling and deglaciation in the Amazonian and Noachian of Mars. 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014) 1227.pdf

^ Barlow, N. 2008. Mars: An Introduction to its Interior, Surface and Atmosphere. Cambridge University Press

^

ISBN 978-0-387-48925-4

^

ISBN 978-0-521-82956-4

^ Connerney, J. et al. 1999. Magnetic lineations in the ancient crust of Mars. Science: 284. 794-798.

^ Langlais, B. et al. 2004. Crustal magnetic field of Mars. Journal of Geophysical Research. 109: EO2008

^ Connerney, J.; Acuña, MH; Ness, NF; Kletetschka, G; Mitchell, DL; Lin, RP; Reme, H; et al. (2005). "Tectonic implications of Mars crustal magnetism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 102 (42): 14970–14975. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10214970C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507469102. PMC 1250232. PMID 16217034.

^ Acuna, M.; Connerney, JE; Ness, NF; Lin, RP; Mitchell, D; Carlson, CW; McFadden, J; Anderson, KA; et al. (1999). "Global distribution of crustal magnetization discovered by the Mars Global Surveyor MAG/ER Experiment". Science. 284 (5415): 790–793. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..790A. doi:10.1126/science.284.5415.790. PMID 10221908.CS1 maint: Explicit use of et al. (link)

^ http://sci.esa.int/science-e/www/object/index.cfm?fobjectid=31028&fbodylongid=645

Recommended reading

- Grotzinger, J. and R. Milliken (eds.). 2012. Sedimentary Geology of Mars. SEPM.

- Lorenz, R. 2014. The Dune Whisperers. The Planetary Report: 34, 1, 8-14

- Lorenz, R., J. Zimbelman. 2014. Dune Worlds: How Windblown Sand Shapes Planetary Landscapes. Springer Praxis Books / Geophysical Sciences.

External links

- Martian Ice - Jim Secosky - 16th Annual International Mars Society Convention